Introduction

Parenting is a complex task, with many challenges along the way that necessitate self-regulation of emotion and arousal to assist the child with his development of self-regulation, social communication, and to limit and redirect normative hostile aggression during this sensitive developmental period in early childhood (i.e., mutual regulation, [Reference Tremblay, Nagin, Seguin, Zoccolillo, Zelazo and Boivin1]. This parental function relies in part on the ability to infer mental states in self and in one’s child (i.e., mentalization, [Reference Slade, Grienenberger, Bernbach, Levy and Locker2]. A multitude of factors, such as parents’ psychopathology, a history of exposure to interpersonal violence (IPV), including child physical and/or sexual abuse, not to mention daily life stresses may interfere with a parent’s capacity to participate in the mutual regulation of emotion and arousal. Outcomes for children of parents, whose psychological impairment and/or distress preclude(s) their effective participation in mutual regulation during this early period, can include various forms of behavioral difficulties and psychopathology, which in turn may interfere with learning and socialization, impaired development of social cognition, as well as altered mental representations of human relationships, both for themselves and their caregivers [Reference Berg-Nielsen, Vikan and Dahl3–Reference Ladd, Pettit and Bornstein5].

The link between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and commonly comorbid conditions has been thoroughly studied in recent decades. Approximately 80% of women and 90% of men with PTSD have at least one other psychiatric diagnosis, approximately half of them (44% of women and 59% of men) having three or more [Reference Brady, Killeen, Brewerton and Lucerini6]. The most common forms of other psychopathology associated with PTSD are substance abuse and affective disorders (e.g., depression, dysthymia, [Reference Brady, Killeen, Brewerton and Lucerini6, Reference Keane and Kaloupek7]). Parental PTSD has been shown to increase parenting stress and reduce maternal sensitivity (i.e., the capacity to understand and respond appropriately to the child’s attachment signals, [Reference Suardi, Moser, Sancho Rossignol, Manini, Vital and Merminod8]). Additionally, PTSD in the context of increased childhood adversity (i.e., early abuse and violence exposure) is also associated with lower parental reflective functioning (PRF), i.e., as a measure of mentalization that is the parent’s ability to infer the child’s thoughts, feelings, and mental states [Reference Suardi, Moser, Sancho Rossignol, Manini, Vital and Merminod8]. PTSD resulting from childhood adversity associates also with symptoms of alexithymia (i.e., the difficulty in identifying and naming one’s own and others’ emotions, [Reference Frewen, Dozois, Neufeld and Lanius9, Reference Schechter, Suardi, Manini, Cordero, Rossignol and Merminod10]).

These relationships are complicated by the fact that many of these factors are associated with one another, such as the various forms of trauma-related psychopathology, as well as measures of alexithymia, socioeconomic status (SES), PRF, and maternal sensitivity [Reference Brady, Killeen, Brewerton and Lucerini6, Reference Nobre‐Trindade, Caçador, Canavarro and Moreira11–Reference Lane, Sechrest and Riedel14] which have multiple interrelations. The same is true for child outcomes: different factors show a complex pattern of univariate associations with each other. Different forms of child psychopathology are associated with each other [Reference Caron and Rutter15], and can be linked to child mental representations of relationships [Reference Belden, Sullivan and Luby16, Reference Warren, Emde and Sroufe17], social behaviors and aggression [Reference Kim, Lee, Lee, Han, Min and Song18], and child temperament [Reference Nigg19]. While examining each of these factors individually is undoubtedly useful, this complex pattern of relationships suggests that a multivariate dimensional approach may be necessary to capture and then interpret the overall data and to quantify the individual impact of different measures.

The aim of this study was therefore to investigate the prospective longitudinal associations of maternal measures when children were toddlers, with child outcomes when children were 5–9 years old. The sample consisted of approximately 2/3 mothers with a history of PTSD in the context of a history of childhood physical abuse, domestic violence exposure, and adult domestic and other violent victimization. Apart from violence-related measures, maternal measures also focused on mothers’ capacity to interact with and understand their child. For children, we wanted to examine potentially less debilitating but generally applicable outcomes, such as emotional comprehension, children’s representations of their parent(s) and relationship with their parent(s), as well as maternal report of child temperament, and bullying and victimization by bullies. Finally, we were also particularly interested in continuous measures of child psychopathology as marked by number of symptoms in a structured clinical interview of the child and parent. In order to incorporate such diverse outcomes, we used a multivariate analysis approach called sparse canonical correlation analysis (sCCA, see methods). sCCA investigates associations of entire datasets (as opposed to—for example—multiple regression analysis which investigates associations of multiple variables with only one outcome variable). In this case, we used it to associate maternal and demographic measures when children were 1–3.5 years old with a dataset of child outcomes when children were school-age (5–9 years old). Importantly sCCA allows for quantification of the importance of different variables in concert (i.e., variables of the same dataset are not necessarily weighed down because they explain overlapping variance as is the case in multiple regression). This was partially because while negative outcomes for children of mothers with pathology seem likely, how their weights affect different developmental stages (such as school-age here) is largely unknown. A central reason for using sCCA was to allow a theory-agnostic statistical approach, which does not force a focus on a single relationship between the datasets but rather allows the algorithm to drive how the datasets are best associated.

We hypothesized that maternal psychopathology and the quality of maternal interactive behavior would be related to child psychopathological symptoms and maladaptive behaviors.

More specifically among these behaviors, we hypothesized that maternal IPV-PTSD affecting the mother–child relationship as manifested by decreased maternal sensitivity during formative development of emotion regulation at ages 1–3.5 years would predict child peer-directed bullying and being bullied at school-ages 5–9 years as possibly a further predictor of intergenerational risk for perpetration of IVP vs IVP victimization.

Methods

Study procedure and sample

We obtained approval from the Geneva University Hospitals’ institutional ethics committee (14-271). The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Mothers gave informed consent for themselves and their children. The project is longitudinal in nature, wherefore this study refers to Phase 1, at which children (56% boys) were 1–3.5 years of age (mean = 27 months, standard deviation [SD] = 8.6), and Phase 2, at which children were 5–9 years old (mean = 84 months, SD = 12.9). This period is associated with the formation of self-regulation of emotion and the acquisition of rudimentary mentalization (i.e., reflective functioning) [Reference Schipper and Petermann20–Reference Engel and Gunnar22].

Mother–child dyads were excluded: (1) If mothers self-reported actively abusing substances, (2) suffered from a psychotic disorder, or (3) if mother or child were otherwise physically and/or mentally unable to participate in the tasks.

At Phase 2, participants were included when children were ages 5–9 years-old. After collecting informed consent, 64 mother–child dyads participated in Phase 2 of the Geneva Early Childhood Stress Study (76% retention). Two dyads were excluded due to more than 20% of data being missing. Among the remaining 62 dyads, 40 mothers had experienced significant PTSD symptoms during their lifetime (CAPS score > = 40; age mean = 39.3, SD = 5.8; 55% boys; children’s age mean = 83.2 months, SD = 13.7). Twenty-two mothers had not (age mean = 40.5, SD = 5.3; 59% boys; children’s age mean = 85.4 months, SD = 11.5, see Table 1). For more on recruitment, exclusion criteria and additional sample information, see Supplementary Material.

Table 1. Sample characteristics and selected measures compared by group.

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; CAPS, clinician-administered PTSD scale; PCL-S, posttraumatic stress disorder checklist scale; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; SD, standard deviation.

Data collection and measures

Phase 1

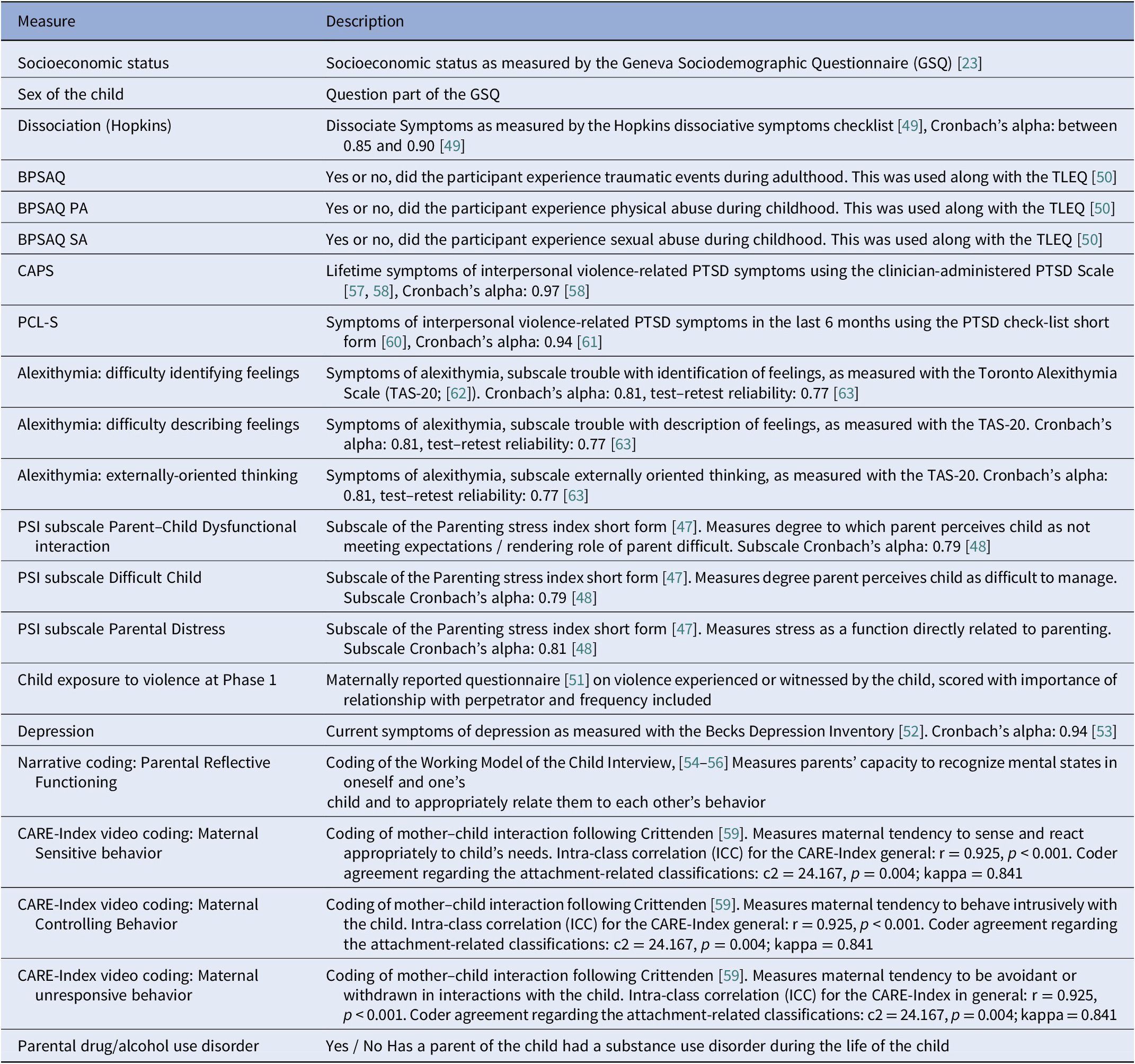

Twenty-one measures from Phase 1 were included in the analysis (see Table 2 for description of measures). Nineteen of them included data on maternal psychopathology (5 measures), experienced abuse during childhood (3 measures) as well as parental behaviors, skills and tendencies (11 measures).

Table 2. Measures of maternal dataset including maternal variables during Phase 1 as well as selected potential confounders.

Abbreviations: BPSAQ, brief physical and sexual abuse questionnaire; CAPS, clinician-administered PTSD scale; GSQ, Geneva sociodemographic questionnaire; PA, physical abuse; PCL-S, posttraumatic stress disorder checklist scale; PSI, parenting stress index; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; SA, sexual abuse; TAS-20, Toronto Alexithymia scale.

Additionally, SES and child sex were included, using the Geneva Sociodemographic Questionnaire [Reference Sancho Rossignol, Lütthi Faivre, Suardi, Moser, Cordero and Rusconi Serpa23]. While these were not predictors of interest, this approach allowed us to quantify their impact on results compared to other measures rather than having to regress out their effect and thereby altering the data set. We wanted to avoid the latter, as these factors are known to be related to some of the other input or outcome measures.

Phase 2

Twenty-five measures were included (19 in Analysis 1), as shown in Table 3. These included number of child psychopathology symptoms (five measures), as well as measures of child exposure to criminal and traumatic events, bullying (two measures), emotion comprehension (three measures) and MacArthur Story Stem Battery (MSSB, [Reference Bretherton, Oppenheim, Buchsbaum and Emde24]) assessed children’s representations of their parents and their emotions (eight measures).

Table 3. Measures of child outcome dataset at Phase 2.

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; CBCL, Child Behavior Checklist; K-SADS, Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-aged Children; MSSB, MacArthur Story Stem Battery; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; SATI, School-Age Temperament Inventory; VEX-R, Violence Exposure Scale—Revised.

a As reported by the mother, only part of Analysis 2, but not of Analysis 1 analysis.

Furthermore, for Analysis 2, maternal report on internalizing and externalizing symptoms in children and four measures concerned with child temperament were added. All measures were validated and possess good to very good psychometrics (Tables 2 and 3).

Data analysis

To incorporate the diverse outcomes and measures described above, we used (sparse) canonical correlation analysis (sCCA, [Reference Witten, Tibshirani and Hastie25, Reference Ing, Samann, Chu, Tay, Biondo and Robert26]), which allows for data-driven quantification of the importance of included variables and a better understanding of the interassociation of complex datasets in a dimensional way beyond what is possible with usual univariate approaches.

We then performed sCCAs to investigate the association of Phase 1 data on mothers (and potential confounders) with child-relevant data from Phase 2. Briefly, the sCCA algorithm assigns weights to each variable such that when multiplied with participant scores on those variables, a variate for each dataset is created, which represents this dataset. These variates are then correlated. Using an L1-norm penalty sCCA also allows to reduce the weights of variables to 0 with the goal to reduce the impact of potentially spurious associations. Within the given parameters, sCCA is designed to assign weights in such a way that the correlation of such variates is maximized. The weights of the variables could be interpreted as representing their importance to the model and usually indicate that the variable is associated with the variate of the other dataset. More specifically, a high weight for a variable of Phase 1 dataset indicates that the model assigns it high importance for predicting the selected outcomes of Phase 2 dataset (as represented in the variate of that data set). The P-value represents the fraction of the 10′000 permutations of the data that showed a higher correlation than the original data. For further information on how sCCA was applied here—including L1-norm—penalties, see the Supplementary Material.

Because maternal report of their children’s psychopathology could potentially be affected by mothers’ own biases linked to her psychopathology, personality, and interpersonal skills, we first performed an analysis in which maternal factors at Phase 1 were associated exclusively with child outcome measures that were self-reported by children or administered by clinicians. However, because parents often provide insights into their children’s symptoms and behaviors that their children may not otherwise report [Reference Miragoli, Balzarotti, Camisasca and Di Blasio27], we decided in a second step to include maternal reports of child symptoms, behaviors, and temperament.

Both sCCA analyses included Phase 1 dataset with 19 maternal psychopathology and behavior variables and 2 variables that were included to quantify potential confounders (see Table 2).

The first sCCA analysis (Analysis 1) included Phase 2 dataset with 19 child behavior and pathology measures, all of which were measured during experiments or reported by the child himself or a clinician (see Table 3). The second sCCA (Analysis 2) included six additional measures in Phase 2 dataset, which were maternally reported observations concerning the child (see Table 3). The reason we did not include these six variables in the first analysis was to be sure that results would not depend on potential maternal reporting biases in our analysis of the associations between Phase 1 and Phase 2 data.

Reliability and power analysis

To assess whether our results were robust and reliable, we proceeded in five steps of reliability analyses: (1) leave-one-out analysis, (2) Moser’s RR-score [Reference Moser, Doucet, Lee, Rasgon, Krinsky and Leibu28], (3) a cross-validation, (4) repeating sCCA with regressing out age, and (5) repeating sCCA transforming each variable into ranks. In order to assess statistical power, we performed Monte Carlo-style power analysis (see Supplementary Material for details).

Results

Groups did not differ on maternal or child-age at either time point; however, as expected, they did differ on PTSD symptom severity (p < 0.001 for both lifetime and current PTSD). See Table 1 for characteristics and group differences of demographic and other selected measures.

The initial sCCA (Analysis 1, using Phase 1 maternal variables and Phase 2 child and clinician-reported variables) showed a significant first mode (r = 0.63, p = 0.030). For Analysis 1, the biggest contributions to the variate of Phase 1 came from current and lifetime PTSD symptoms (weight = 0.39 and 0.35, respectively), depression (weight = 0.35), report of parental distress on the PSI (weight = 0.33), as well as dissociation symptoms (weight = 0.31). Additionally, maternal report of the child being exposed to violence already at Phase 1 (weight = 0.33) also contributed with a weight above 0.2 to the variate of Phase 1. Additionally, SES also contributed with a weight of 0.23 (see Figure 1 and Table 4). The number of child symptoms for PTSD (weight = 0.55), anxiety disorders (weight = 0.38), ADHD (weight = 0.28) and depression (weight = 0.25), as well as bullying perpetration (weight = 0.38) and victimization (weight = 0.27) contributed to the variate representing Phase 2. Child attributions of parents being harsh as rated via the MSSB also had a positive weight (0.22, see Figure 1 and Table 4).

Figure 1. Results of the first sCCA analysis. Top left assigned weights (>0.2) of Mode 1 for Phase 1 variate, Top right scatter plot of mode 1, stratified by maternal PTSD status and child sex for illustrative purposes. Bottom left: significance and reliability measures, bottom right weights (>0.2) for Phase 2 variate. BDI, beck depression inventory; CBCL, child behavior checklist, IPV, interpersonal violence; PCL-S, posttraumatic stress disorder checklist scale, PSI, parenting stress index ; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; TAS20, Toronto Alexithymia scale.

Table 4. Weight contributions of the first modes of sparse canonical Analyses 1 and 2. (A) For Phase 1 maternal dataset; (B) for Phase 2 Child dataset.

Note: Table 4 weights of sCCA analyses. Analysis 1 includes only child measures given by clinician, experiment, or children themselves, while Analysis 2 also includes maternally reported child measures as outcomes.

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; CBCL, child behavior checklist; MSSB, Macarthur story stem battery; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; VEX, violence exposure scale—revised.

The sCCA of Analysis 2 (additionally using maternally reported child variables for Phase 2) was more significant (r = 0.69, p = 0.003) than Analysis 1. The weights defining the variate of Phase 1 were again led by psychopathology measures, with PTSD (lifetime weight = 0.36, current PTSD weight = 0.35), dissociation (weight = 0.34), and depression symptoms (weight = 0.32) contributing the most. Other variables contributing with a weight above 0.2 included all PSI subscales (weights = 0.30, 0.26, and 0.25, respectively), and the alexithymia subscale for identification of feelings (weight = 0.22). Additionally, potential confounder variables of child sex (weight for girls = 0.24) and maternal report of child exposure to violence at Phase 1 (weight = 0.23) also contributed (see Figure 2 and Table 4). The variate representing Phase 2 was contributed with weights >0.20 by the number of child symptoms for PTSD (weight = 0.41) and anxiety disorders (weight = 0.27), as well as bullying perpetration (weight = 0.27) and victimization (weight = 0.20). Several of the maternally reported variables added for Analysis 2 also had weights >0.20, including internalizing (weight = 0.35) and externalizing symptoms (weight = 0.22), as well as school life temperament measures for negative reactivity (weight = 0.39) and task persistence (weight = 0.32, see Figure 2 and Table 4).

Figure 2. Results of the second sCCA analysis. Top left assigned weights (>0.2) of Mode 1 for Phase 1 variate, Top right scatter plot of mode 1 stratified by maternal PTSD status and child sex for illustrative purposes. Bottom left: significance and reliability measures, bottom right weights (>0.2) for Phase 2 variate. BDI, beck depression inventory; CBCL, child behavior checklist; PCL-S, posttraumatic stress disorder checklist scale; PSI, parenting stress index; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; IPV, interpersonal violence; TAS20, Toronto Alexithymia scale.

Reliability analysis indicated that mode 1 (but no other modes) of Analyses 1 and 2 was reliable (see Supplementary Material). We calculated that power was more than adequate to find an existing significant effect (see Supplementary Material).

Discussion

We found a dimensional relationship between (1) a maternal dataset from when children were toddlers that reflects maternal lifetime experience of IPV and related psychopathology (i.e., PTSD, depression, and dissociation), parenting stress, and the quality of maternal interactive behavior (i.e., maternal sensitivity) and (2) a follow-up dataset with a focus on child outcome measures from when the same children were school-aged that reflects child symptoms, behaviors including peer-aggression (i.e., bullying) and victimization. This relationship between maternal data and subsequent child outcomes was multivariate and dimensional in nature concerning both maternal predictors and child outcomes.

PTSD and comorbid psychopathology most strongly influenced the model among both maternal and child measures. However, among maternal predictors of child outcome, maternal psychopathology was accompanied by other measures related to stress, alexithymia, and atypical behavior, some of which reached almost the same weight. For the subsequent child dataset, it is important to note that the child’s PTSD-like symptoms were most influential again, accompanied by other psychopathology symptoms (i.e., ADHD, depression, and anxiety). However, other variables were also important. The fact that bullying and being bullied, carried notable weight, underscores the long-term effects of the family environment on children’s social interaction and how their behavior can in turn affect their peer-interactions and therefore affect society from a broader perspective.

These latter results support our hypothesis that, during early childhood, maternal PTSD symptom severity along with decreased maternal sensitivity with which PTSD severity is also associated [Reference Suardi, Moser, Sancho Rossignol, Manini, Vital and Merminod8, Reference Schechter, Suardi, Manini, Cordero, Rossignol and Merminod10], and predict increased peer-aggression and -victimization at school-age. This finding to our knowledge is a novel finding that contributes to our understanding of the influence of maternal IVP-PTSD as it can affect caregiving during the early sensitive period for the development of emotion regulation, on child school-age outcomes and subsequent risk. Further research is needed to explore this potential marker of intergenerational transmission of IVP and related psychopathology and to determine which individual child characteristics would render a child more likely at risk to perpetrate IVP vs be victimized.

An additional, novel, and surprising finding was that maternal PTSD severity during early childhood predicted school-age child attributions of parents as being harsh on the story-stem completion task (MSSB). To the best of our knowledge, no previously published study has studied this aspect of child mental representation or perception of parents during childhood. One published study of adults using retrospective measures had reported the association of offspring representations of parents as harsh and dysfunctional during childhood with family violence and maltreatment and subsequent disturbance in emotion regulation [Reference Talevi, Imburgia, Luperini, Zancla, Collazzoni and Rossi29]. This finding indicates that during clinical examination of children via observation of play narrative, harsh representations of parental figures might lead the clinician to inquire as to intergenerational IPV and associated psychopathology (i.e., IVP-PTSD).

Initial analyses were performed without including maternally reported measures of child psychopathology and temperament to ensure that associations transcended maternal response biases or an otherwise distorted vision of her child (for further discussion on differences between Models 1 and 2, see Supplementary Material). Our findings echo and extend those of several prior studies on parental psychopathology and child outcomes [Reference Suardi, Moser, Sancho Rossignol, Manini, Vital and Merminod8, Reference Zaslow, Weinfield, Gallagher, Hair, Ogawa and Egeland30–Reference Ehrensaft, Cohen, Brown, Smailes, Chen and Johnson33]. Our findings are also in line with another study on maternal intimate partner violence and child experience [Reference Castro, Alcantara-Lopez, Martinez, Fernandez, Sanchez-Meca and Lopez-Soler34]. That study was more focused on PTSD symptoms, considering direct physical abuse alone. This latter study did not examine comorbidities and other explicative factors; yet, similar to this study, it reported that both mothers’ experience of domestic violence, together with mothers’ related PTSD, and those mothers’ children’s history of physical abuse and/or exposure to domestic violence were important predictors of all subscales of the children’s PTSD, when they were between 8 and 17 years of age.

The dimensional nature and breadth of measures studied here—both those pertaining to maternal factors and child outcomes—underscore the complexity of factors to be considered when mothers have a history of violence and abuse. Early intervention targeting mother–child interactive behavior as well as maternal psychopathology, and thus several factors simultaneously, may therefore have long-term benefits for many at-risk individuals, given the prevalence of IPV and related psychopathology [Reference Lieberman, Ghosh Ippen and Van Horn35, Reference Miller36]. Moreover, the large number of child outcomes reflects the complexity and multidimensional (as opposed to a univariate categorical yes or no) nature, of the consequences of growing up during a sensitive period for the development of emotion regulation, in an environment with maternal IPV-related PTSD.

The complexity identified in this study supports and extends preexisting literature on parental PTSD and its potential effects on caregiving. PTSD is indeed associated with several comorbid psychiatric disorders, such as major depressive disorder, which can also affect parenting skills [Reference Berg-Nielsen, Vikan and Dahl3]. PTSD and comorbid depressive and dissociative symptoms, and their combined consequences on parenting skills can have an influence on a variety of child outcome measures and put children at greater risk for psychopathology, deficient socioemotional skills, and propensity for aggressive behavior, such as bullying as well as victimization [Reference Morelen, Shaffer and Suveg4, Reference Ladd, Pettit and Bornstein5].

Given the complexity and number of involved factors, this study highlights important challenges that clinicians face when attempting to prevent the intergenerational transmission of IPV and related psychopathology. It is not only maternal psychopathology, such as PTSD that affects child outcomes, but also the co-occurring problems that often accompany PTSD, generally increased parenting stress [Reference McDonald, Slade, Spiby and Iles37] and decreased parental sensitive responsiveness in parent–child interactions [Reference Suardi, Moser, Sancho Rossignol, Manini, Vital and Merminod8, Reference Schechter, Suardi, Manini, Cordero, Rossignol and Merminod10]. Simply treating maternal PTSD symptoms can be an important start, yet such individual treatment is unlikely to be sufficient to address all accompanying problems in the parent–child relationship, such as low PRF as a marker of the quality of the parent’s attachment (i.e., attachment security and organization, 2, [Reference Grienenberger, Kelly and Slade38–Reference Moser, Suardi, Rossignol, Vital, Manini and Serpa40]), as well as proneness to additional traumatization in the context of low SES [Reference Burns, Zunt, Hernandez, Wagenaar, Kumar and Omolo41–Reference Voss, Chiang, Wang, McLaughlin and Miller44] and a tendency to misappraise interpersonal cues that would alert a mother to a risk for violence in a new romantic relationship according to a nested study of a subset of the same mothers that participated in this larger study [Reference Berthelot, Lemieux, Garon-Bissonnette, Lacharité and Muzik45, Reference Perizzolo Pointet, Moser, Vital, Serpa, Todorov and Schechter46]. The consequences of the combination of co-occurring risk factors for young children encompass a range of factors themselves. These include different kinds of psychopathology and behavioral difficulties, among which are increased likelihood of the perpetration of aggression and victimization. It is thus important to keep an open mind in family situations with histories of IPV and to monitor different kinds of symptoms and potentially ensuing difficulties for the children of parents with IPV-PTSD.

Limitations of this study are, however, those of the sample and the chosen measures. The focus of the sample on dyads in which the majority of mothers had experienced PTSD symptoms and childhood exposure to IPV permitted a good understanding of the intergenerational consequences of IPV. However, this focus on an important but very specific clinical population may make generalization to the larger population more difficult. While the extensive reliability and power analysis conducted for this study indicate the findings as reliable (see Supplementary Material), it is possible that with more statistical power, a secondary sCCA mode focusing more on externalizing and aggression symptoms could have become significant and reliable. Further, while we believe that the chosen measures make sense within these datasets, they are by no means the only ones that might relate to the intergenerational cycle of violence, and future studies may want to widen the scope even further.

In conclusion, this is the first study to our knowledge to report prospective, longitudinal findings of a sample of children of mothers who suffered from IVP-PTSD during early childhood and who were later studied using a range of different measures—both observed, child-reported, and maternal reported at school-age. Our study shows the complex dimensionality with which a multitude of factors around IPV-related PTSD affect mother–child dyads prospectively and longitudinally. We argue that this points to the importance of understanding the transgenerational transmission of violence-related psychopathology as a multifactor phenomenon, both in origin and outcome, that is best described dimensionally rather than categorically (such as the presence of disorder yes/no). Children’s social–emotional skills, not just symptoms, are reflected in the outcome measures selected, thereby providing an opportunity to observe distortions in children’s understanding of relational meanings emerging in middle childhood. A particularly novel finding of this study involves the demonstration that maternal severity of PTSD and the quality (i.e., sensitivity) of related mother–child interactive behavior during early childhood, predicts peer-aggression (i.e. bullying) and -victimization at school-age. The results, in sum, imply the importance of focusing on traumatized parents’ behavioral response to their young children’s distress during the clinical intervention. This plus attention to the inner worlds of parents and children—the latter, which the study characterized via the MacArthur Story Stem Battery as an observed behavioral and narrative measure, are propitious targets for restoring a healthier social–emotional developmental trajectory by school-age.

Abbreviations

- ADHD

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

- BDI

beck depression inventory

- CBCL

child behavior checklist

- CAPS

clinician-administered PTSD

- IPV

interpersonal violence

- MSSB

MacArthur story stem battery

- PCL-S

posttraumatic stress disorder checklist scale

- PRF

parental reflective functioning

- PSI

parenting stress index

- PTSD

posttraumatic stress disorder

- sCCA

sparse canonical correlation analysis

- SES

socioeconomic status

- TAS20

Toronto Alexithymia scale

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2023.8.

Author Contribution

All authors have made substantial contributions to: (1) the conception and design of the study, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, (3) final approval of the version to be submitted.

Data Availability Statement

The data used for the analysis is available as a Supplementary Material of this paper.

Financial Support

This study was funded by a Swiss National Science Foundation NCCR-SYNAPSY grant (no. 51AU40_125759).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare none.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.