Introduction

Despite substantial progress to date, mental illness continues to impose a significant burden on young individuals worldwide [Reference Mei, Fitzsimons, Allen, Alvarez‐Jimenez, Amminger and Browne1]. While most of the research has focused on the management of full-blown psychiatric syndromes in adult patients, early intervention and prevention have received comparatively less attention [Reference Fusar-Poli, Correll, Arango, Berk, Patel and Ioannidis2, Reference Uhlhaas, Davey, Mehta, Shah, Torous and Allen3]. Notably, nearly two-thirds of individuals with a mental disorder (62.5%) experience symptoms during adolescence or early adulthood (before the age of 25), with a median onset age of 18 [Reference Solmi, Radua, Olivola, Croce, Soardo and de Pablo4]. These life phases are pivotal for establishing the sociocultural and emotional foundations for the transition into adulthood, and prospective analyses indicate that the onset of a mental disorder during this critical life stage strongly predicts adverse socioeconomic and health outcomes [Reference Skinner, Occhipinti, Song and Hickie5].

From a neuropsychological point of view, research has also highlighted the concept of “sensitive periods,” that is, phases in which risk factors can influence the manifestation of mental health symptoms, thereby providing potential timeframes for early intervention [Reference Uhlhaas, Davey, Mehta, Shah, Torous and Allen3]. These considerations underscore the need to effectively address the mental health needs of young individuals, recognizing youth mental health as a distinct sector and prompting the development of services dedicated to early and preventive interventions [Reference Mei, Fitzsimons, Allen, Alvarez‐Jimenez, Amminger and Browne1].

Autistic traits and a dimensional approach to psychopathology

Autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) are neurodevelopmental conditions characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and interactions, restricted and repetitive interests and behaviors, and altered sensory sensitivity. ASDs often remain unrecognized until adulthood, coming to clinical attention after the onset of other mental disorders, often prompted by life stressors [Reference Kamio, Moriwaki, Takei, Inada, Inokuchi and Takahashi6, Reference Lundström7]. It is now recognized that autism features extend beyond those with a clinical diagnosis, existing on a continuum within the general population and manifesting at milder levels as subthreshold autistic characteristics [8, Reference Constantino and Charman9]. There is also evidence that, even when subthreshold, autistic traits (ATs) may be associated with a higher vulnerability to the development of other psychiatric disorders [Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita, Bertelloni, Diadema, Barberi and Gesi10–Reference Takara and Kondo14].

Current psychopathological research has pointed out the shortcomings of a categorical approach to mental illnesses, emphasizing the limitations of the DSM-5 concept of “comorbidity.” This model is more suitable when there is homogeneity between members of a class, clear boundaries among different classes, and when the classes are mutually exclusive, circumstances that are rarely encountered in clinical practice. On the other hand, a dimensional approach to psychopathology allows the description of patients across multiple syndrome dimensions that, in turn, constitute broad spectra of interrelated psychopathologies [Reference Krueger and Piasecki15]. This approach is even more paramount in consideration of subthreshold symptomatic expression of psychopathology and calls for a novel diagnostic approach [Reference Uhlhaas, Davey, Mehta, Shah, Torous and Allen3].

In light of the aforementioned considerations, this study aimed to characterize the presence of ATs, using a cluster analysis, in a population of young adults seeking specialist assistance. Alongside, the study sought to assess the study population across various psychopathological domains (mood, anxiety, feeding and eating disorders [EDs], symptoms of the psychotic sphere, and personality structure), in order to evaluate their links with ATs.

Methods

Study population

The study included a sample of 263 adolescents and young adults aged 16 to 24 attending the “Centro Giovani Ettore Ponti” (ASST Santi Paolo e Carlo, Milan, Italy), an outpatient clinic open to individuals who are experiencing distress, discomfort, or psychopathological suffering, whether at the onset or already manifested in behaviors or symptomatic expressions of any kind.

Study participants underwent an evaluation by a psychiatrist and a psychologist according to DSM-5-TR criteria [8]. Specifically, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders: Clinical Version (SCID-5-CV) [Reference First, Williams, Karg and Spitzer16] was administered for the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders. The SCID-5-SPQ [Reference Ekselius, Lindström, von Knorring, Bodlund and Kullgren17] and the SCID-5-PD [Reference Shankman, Funkhouser, Klein, Davila, Lerner and Hee18] were used, respectively, for screening and diagnosis of personality disorders. Informed written consent was obtained from every participant after a complete description of the study and with the opportunity to ask questions. Subjects were not paid for their participation and were free to withdraw from the study at any time without giving further explanation.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee of the ASST Santi Paolo e Carlo of Milan approved all recruitment and assessment procedures.

Psychometric instruments

In order to collect specific information for the study, the following self-report questionnaires were administered: (i) the Autism Quotient [Reference Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright, Skinner, Martin and Clubley19], designed to measure the extent to which an adult without intellectual disabilities exhibits ATs; (ii) the Ritvo Autism and Asperger Diagnostic Scale-Revised, RAADS-R [Reference Ritvo, Ritvo, Guthrie, Ritvo, Hufnagel and McMahon20], usually implemented in clinical settings to support the diagnosis of ASDs without intellectual disabilities; (iii) the Empathy Quotient, EQ [Reference Baron-Cohen and Wheelwright21], to assess the level of cognitive and affective empathy; (iv) the Sensory Perception Quotient – Short Form, SPQ-SF35 [Reference Tavassoli, Hoekstra and Baron-Cohen22], which investigates hypersensitivity or hyposensitivity across the five sensory modalities (sight, hearing, smell, touch, and taste) and has demonstrated good discriminatory ability between adults with ASDs and neurotypical individuals; (v) the Beck Depression Inventory, BDI-II [Reference Beck, Steer and Brown23], for the evaluation of depressive symptoms; (vi) the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory [Reference Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagg and Jacobs24], for measuring state anxiety, which is experienced in response to a situation (STAI-Y1), and trait anxiety (STAI-Y2), which is a part of personality; (vii) the Eating Attitude Test-26 items, EAT-26 [Reference Dotti and Lazzari25, Reference Garner, Olmsted, Bohr and Garfinkel26], for the assessment of the symptoms and specific concerns of EDs; (viii) the Prodromal Questionnaire–short version, PQ-16 [Reference Ising, Veling, Loewy, Rietveld, Rietdijk and Dragt27], for the identification of prodromal symptoms of psychosis; (ix) the Personality Inventory for DSM-5, PID-5-BF [Reference Krueger, Derringer, Markon, Watson and Skodol28], used to evaluate the personality structure according to the alternative dimensional model of the DSM-5; (x) the Pathological Narcissism Inventory, PNI [Reference Fossati and Borroni29, Reference Pincus, Ansell, Pimentel, Cain, Wright and Levy30], which investigates the levels of narcissistic grandiosity and vulnerability. For each of the abovementioned scales, the validated Italian version was administered to the patients.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all sociodemographic, clinical, and psychometric variables; in particular, we analyzed the frequencies of patients scoring above the cutoff on screening questionnaires. Statistical significance was defined at α < 0.05, and all tests performed were two-tailed. A K-means cluster analysis based on the standardized AQ, RAADS, EQ, and SPQ total scores was performed in order to evaluate the specific distribution of autism spectrum-related measures in distinct but homogeneous groups. We used squared Euclidean distance for the divergence measure between cases. The method of iterative updating of clustered centroids was chosen for classifying cases, with the new clusters’ centers being calculated after all cases are assigned to a given cluster. The solution for K = 3 (i.e., three clusters) was the most satisfactory with small within-cluster variability compared to the differences between the centroids of the clusters. Subsequently, we performed chi-square tests in order to compare categorical variables (gender, scores above or below BDI-II, STAI, EAT-26, and PQ-16 cutoffs) among clusters. In the case of gender and the presence/absence of a score above the cutoff at STAI-Y2, Fisher’s exact p-value was also reported as some cells showed an expected count lower than 5.

The Kruskal–Wallis test was used for comparing continuous variables (BDI-II, STAI, EAT-26, PQ-16, PID-5-BF, and PNI scores).

Finally, a discriminant analysis was carried out on the three cluster groups in order to confirm the results of the cluster analysis and to identify the weights of BDI-II, STAI, EAT-26, PNI, PID-5-BF, and PQ-16 scores in discriminating groups.

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Science, version 29.0 (SPSS Inc.).

Results

The mean age of our sample was 19.57 years (± 2.02). Most of the participants (158, 60.08%) identified themselves with the female gender, 88 subjects (33.46%) identified with the male gender, 12 (4.56%) declared themselves nonbinary, and 5 (1.90%) preferred not to disclose their gender. The average BMI was 22.60 kg/h2 (± 5.15): in particular, 49 (18.63%) participants were underweight (i.e., BMI below 18.5 kg/h2), 152 (57.78%) had a healthy weight (18.5 < BMI < 25 kg/h2), 41 (15.60%) participants were overweight (25 < BMI < 30 kg/h2), and 21 (7.99%) participants were obese (BMI above 30 kg/h2). Further sociodemographic information is reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Sociodemographic information

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; F, female; M, male; N, numerosity; SD, standard deviation; %, percentage.

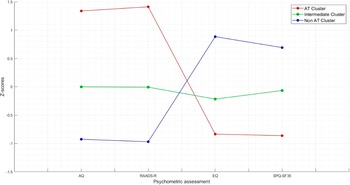

The K-means cluster analysis met criterion 0 of convergence at the tenth iteration. The three clusters of subjects determined by the K-means cluster analysis were defined as AT cluster (n = 59, 22.43%), intermediate cluster (n = 119, 45.25%), and no-AT cluster (n = 85, 32.32%). Figure 1 shows the z-score values of AQ, RAADS, EQ, and SPQ total scores in the three clusters. The distance between AT and no-AT cluster centers was 4.021, the distance between AT and intermediate cluster centers was 2.196, and the distance between no-AT and intermediate cluster centers was 1.889. The average distance of cases from their cluster center was 1.239 ± 0.515. The dispersion analysis showed that AQ and RAADS scores were those with the greatest influence in forming clusters (F = 277.872 and F = 397.771, respectively) (Table 2).

Figure 1. Z-score values of AQ, RAADS, EQ, and SPQ total scores in the three clusters.

Table 2. Dispersion analysis for cluster analysis based on AQ, RAADS-r, EQ, and SPQ-SF35 total scores

Abbreviations: AQ, autism quotient; EQ, empathy quotient; RAADS-R, Ritvo Autism and Asperger Diagnostic Scale-Revised; SE, standard error; SPQ-SF35, Sensory Perception Quotient Short Form.

A significant difference in gender distribution emerged for the clusters (chi-square = 32.012; p < .001, Fisher’s exact p < .001). Females were significantly more represented in the no-AT group (n = 65; 76.5%) than in AT (n = 31; 54.4%) and intermediate ones (n = 62; 53.4%). Males were significantly more represented in the intermediate group (n = 52; 44.8%) than in the no-AT one (n = 19; 22.4%), while an in-between proportion was reported in the AT group (n = 17; 29.8%). Nonbinary subjects were significantly more represented in the AT group (n = 9; 15.8%) than in the no-AT (n = 1; 1.2%) and intermediate (n = 2; 1.7%). Five subjects (2 in the AT group and 3 in the intermediate group) preferred to not disclose their gender.

According to the Kruskal–Wallis analysis, subjects in the no-AT cluster scored significantly lower than the AT cluster on BDI-II total scores (data available for 193 subjects), and STAI-Y2 (data available for 196 subjects) scores. Noticeably, for STAI-Y1, AT subjects also reported significantly higher scores than intermediate cluster participants, while for STAI-Y2, AT and intermediate cluster groups did not score significantly different, both reporting a significantly higher score than no-AT group (Table 3). No difference was reported in the proportion of subjects scoring above the BDI-II cutoff: AT group = 38 (90.5%), intermediate group = 72 (83.7%), and no-AT group = 49 (75.4%); chi-square = 4.195, p = .127. Similarly, no difference emerged in the proportion of subjects scoring above the STAI cutoffs, although a tendency toward significance is observable for STAI-Y2. STAI-Y1: AT group = 38 (92.7%), intermediate group = 74 (83.1%), and no-AT group = 52 (78.8%); chi-square = 3.607, p = .161. STAI-Y2: AT group = 40 (97.6%), intermediate group = 86 (96.6%), and no-AT group = 57 (87.7%); chi-square = 6.436, p = .049, Fisher’s exact p = .051.

Table 3. Comparison of BDI-II and STAI, EAT-26, PQ-16, PID-5-BF, and PNI scores among cluster groups

Abbreviations: AT, autistic trait; BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory – Second Edition; EAT-26, Eating Attitude Test-26 items; PID-5-BF, Personality Inventory for DSM-5-Brief From; PNI, Pathological Narcissism Inventory; PQ-16, Prodromal Questionnaire Short Version; STAI-Y1, State–Trait Anxiety Inventory – State Anxiety; STAI-Y2, State–Trait Anxiety Inventory – Trait Anxiety.

Subjects in the AT cluster scored significantly higher than the other two on EAT-26 total and domain scores (Table 3), while for PQ-16 (data available for 198 subjects) the only significant difference was reported between AT and no-AT clusters, the latter scoring significantly lower than the first at both symptom and distress scores (Table 3). Moreover, the AT group reported a significantly higher proportion of subjects scoring above the cutoff of EAT-26 when compared with the other two groups: AT group = 24 (40.7%), intermediate group = 23 (19.3%), and no-AT group = 15 (17.6%); chi-square = 12.428, p = .002. The AT group also reported a significantly higher proportion of subjects scoring above the cutoff of PQ-16, only when compared with the no-AT group: AT group = 18 (40.0%), intermediate group = 21 (23.6%), and no-AT group = 9 (13.8%); chi-square = 9.962, p = .007.

Considering the PID-5 BF scale (data available for 181 subjects), AT subjects scored significantly higher than the other two clusters on the total score and on Detachment and Disinhibition factors, while for the Negative affect factor the AT cluster scored only higher than the no-AT one. For Psychoticism, AT subjects scored significantly higher than the other two clusters, while, in turn, the intermediate cluster scored higher than the no-AT one. No significant difference was found for the Antagonism factor (Table 3).

Finally, on PNI, AT and intermediate cluster groups scored significantly higher than the no-AT group on total scores; no significant differences were reported for Narcissistic grandiosity factor and for the subscales Exploitativeness, Self-sacrificing Self-enhancement, while AT and intermediate clusters scored higher than no-AT on Grandiose fantasy and Entitlement rage. On the other hand, AT group scored significantly higher than the intermediate cluster on Narcissistic vulnerability, which in turn scored higher than the no-AT one. In all the three subscales of Contingent Self-esteem, Hiding the self, and Devaluing, AT subjects scored higher than no-AT ones, while the intermediate cluster scored higher than the no-AT only on Contingent self-esteem and Devaluing (Table 3).

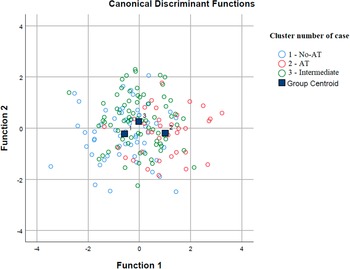

According to the discrimination analysis, two functions were identified: function 1 adsorbed most of the variance (85.9%), while function 2 absorbed 14.1% of the variance (Table 4 and Figure 2). The discriminating elements in function 1, in order of higher discriminant value, were PID-5-BF total, STAI-Y2 total, EAT-26 total, STAI-Y1 total, PQ-16 symptoms total, BDI-II total, and PNI Narcissistic vulnerability total. Function 2 was represented only by the PNI Narcissistic grandiosity total (Table 5).

Table 4. Summary of canonical discriminant functions for discriminant analysis

Figure 2. Discriminant analysis: group graphic.

Table 5. Structure matrix for discriminant analysis

* Largest absolute correlation between each variable and any discriminant function.

Discussion

The characterization of the sample based on the prevalence of ATs, empathy, and sensory sensitivity allowed the identification of three clusters of subjects, namely, a group in which ATs were highly prevalent (AT cluster), another in which such features were not present (no-AT cluster), and a subset of participants showing an intermediate pattern of AT expression (intermediate cluster). Of the aforementioned clinical and psychopathological features, the AT prevalence was the one driving the identification of the clusters.

Regarding sex distribution within clusters, and particularly the higher prevalence of female subjects in the no-AT cluster, our findings reflect the psychometric properties of the AQ and RAADS questionnaires. The AQ was originally validated in a predominantly male sample [Reference Allison, Auyeung and Baron-Cohen31], and though a potential specific female presentation of ASDs has emerged in literature [Reference Lai, Lombardo, Auyeung, Chakrabarti and Baron-Cohen32–Reference Rynkiewicz, Lassalle, King, Smith, Mazur and Podgórska-Bednarz35], most psychometric scales for assessing ASDs are constructed on the classical phenotype of the disorder, thereby being more accurate in identifying male patients with ASDs [Reference Hull, Petrides and Mandy36–Reference Rynkiewicz, Janas-Kozik and Słopień40]. Even though the prevalence of male subjects was higher in the intermediate cluster compared to the AT cluster, male subjects still comprise almost 50% of the intermediate cluster. This is even more relevant considering the overall female predominance of the total sample. The higher prevalence of nonbinary subjects in the AT cluster is consistent with existing literature on the distribution of ATs in both general and clinical populations [Reference Kung41]. For instance, another study has reported that transgender and gender-diverse individuals scored significantly higher on self-report measures of ATs compared to cisgender individuals [Reference Warrier, Greenberg, Weir, Buckingham, Smith and Lai42].

In the present study, individuals with a higher prevalence of ATs displayed overall greater symptomatology across various psychopathological dimensions, including mood, anxiety, severity of EDs, psychotic symptoms, and personality structure. This is in line with recent literature about the relationship between ATs and other psychiatric disorders [Reference Fietz, Valencia and Silani43, Reference Lundström, Chang, Kerekes, Gumpert, Råstam and Gillberg44].

In our sample, there was not a statistically significant difference between the clusters with regard to the number of subjects scoring above the cutoff at BDI-II and STAI-Y1/Y2 scales. Nonetheless, subjects in the intermediate and AT clusters exhibited statistically significant higher scores on both scales, thus indicating a higher level of overall affective symptomatology. Previous literature has already highlighted the relationship between ATs and affective disorders, namely, depression, either bipolar or unipolar [Reference Abu-Akel, Clark, Perry, Wood, Forty and Craddock45–Reference Matsuo, Kamio, Takahashi, Ota, Teraishi and Hori48], and anxiety disorders [Reference Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright, Skinner, Martin and Clubley19, Reference Moss, Howlin, Savage, Bolton and Rutter49]. Moreover, studies have focused on the striking clinical similarities between ATs and social anxiety disorder (SAD) manifestations, such as social avoidance, difficulties being in public, and avoidance of eye contact [Reference Muris and Ollendick50–Reference White, Ollendick and Bray52]. These shared features can sometimes make it difficult to adequately distinguish the two conditions in clinical practice [Reference Farrugia and Hudson53], also considering the well-researched frequent comorbidity between full-blown ASDs and SAD [Reference Cath, Ran, Smit, van Balkom and Comijs54–Reference White, Oswald, Ollendick and Scahill57].

The same trend was observed for the scales assessing EDs symptoms and psychosis risk, wherein participants with higher ATs obtained higher scores compared to those in the intermediate and no-AT clusters. There is now a substantial body of literature highlighting the shared psychopathological features between ASDs and EDs (especially, but not exclusively, anorexia nervosa, AN). These include atypical social cognition, difficulties in processing emotions, cognitive rigidity [Reference Brede, Babb, Jones, Elliott, Zanker and Tchanturia58], and an impaired theory of mind [Reference Huke, Turk, Saeidi, Kent and Morgan59]. Furthermore, research indicates a higher prevalence of ATs in both AN [Reference Baron-Cohen, Jaffa, Davies, Auyeung, Allison and Wheelwright60–Reference Tchanturia, Smith, Weineck, Fidanboylu, Kern and Treasure62] and other EDs [Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita, Gesi, Cremone, Corsi and Massimetti12, Reference Vagni, Moscone, Travaglione and Cotugno63].

As for psychotic spectrum disorders and ASDs, an increasing number of papers have pointed out the similarities in the clinical presentation of these conditions, as well as the higher prevalence of ATs in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders (SSDs) and the comorbidity between these syndromes [Reference De Crescenzo, Postorino, Siracusano, Riccioni, Armando and Curatolo64, Reference van Os, Hanssen, Bijl and Strauss65]. Social withdrawal, theory of mind deficits, and cognitive dysfunctions represent shared symptomatologic features between these conditions, and a conspicuous number of studies have identified genetic, biological, and familial overlap between SSDs and ASDs [Reference Carroll and Owen66–Reference Jutla, Foss-Feig and Veenstra-VanderWeele69]. Furthermore, an increased occurrence of schizophrenia has been observed in individuals with ASDs compared to controls [Reference Lai, Kassee, Besney, Bonato, Hull and Mandy70, Reference Zheng, Zheng and Zou71], and this is also true for subthreshold ASD conditions, which show high prevalence rates in psychotic populations [Reference Kincaid, Doris, Shannon and Mulholland72].

The higher scores obtained by AT subjects at the Detachment and Disinhibition domains of the PID-5-BF questionnaire reflect the clinical similarity between some features of ASDs (and ATs) and the anxious-avoidant psychopathological dimension, as noted in prior studies [Reference Carpita, Nardi, Bonelli, Massimetti, Amatori and Cremone73, Reference Dell’Osso, Amatori, Bonelli, Nardi, Massimetti and Cremone74]. Additionally, disinhibition is a commonly observed symptom in full-blown ASDs, and it is worth mentioning that ASDs are often comorbid with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and impulse control disorders [Reference Mannion, Brahm and Leader75–Reference Vannucchi, Masi, Toni, Dell’Osso, Marazziti and Perugi77], which have all been classified among the so-called obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders [Reference Hollander, Kim, Khanna and Pallanti78]. On the other hand, the higher scores observed in the Negative Affect and Psychoticism domains mirror the aforementioned considerations about BDI-II, STAY, and PQ-16 results.

Regarding narcissistic traits, in our study participants with more ATs displayed a higher amount of narcissistic vulnerability. It is now recognized that individuals with vulnerable narcissism face an increased risk of developing mental health conditions. Specifically, the dimensions of hiding and underestimating the self seem to be associated with suicidal ideation and a high frequency of non-suicidal self-harm [Reference Sprio, Mirra, Madeddu, Lopez-Castroman, Blasco-Fontecilla and Di Pierro79]. The presence of greater vulnerable narcissism is also related to social avoidance, anxiety, and internalized depressive manifestations (low self-esteem and shame) [Reference Erkoreka and Navarro80, Reference Miller, Lamkin, Gentile, Lynam and Campbell81]. In line with these findings, our cohort consisted of young individuals seeking psychiatric assistance for various psychopathological concerns. Furthermore, it has been shown that a high prevalence of vulnerable, but not grandiose, narcissistic traits can be found among ASD patients [Reference Broglia, Nisticò, Di Paolo, Faggioli, Bertani and Gambini82], which recalls the definition of “naïve egocentrism” first postulated by Frith and colleagues referring to a certain self-absorption intrinsic to ASDs [Reference Frith and de Vignemont83].

Lastly, the results of our discrimination analysis hint at the possibility that ATs may predispose to an overall greater psychopathological burden. This is evidenced by the accurate separation of AT clusters by the scores obtained at the administered psychometric scales.

The findings of this study must be interpreted in light of the following limitations. First, reliance on self-report scales for data collection may introduce biases due to subjective perceptions and social desirability biases. Second, the available ASDs screening scales might not adequately capture the female phenotype of ASDs, possibly resulting in the oversight of female participants exhibiting ATs. Additionally, the absence of a control group limits the ability to compare the observed findings with those of individuals without psychopathological conditions. Third, we did not include in our analysis important variables such as family history and substance use, since they were not consistently disclosed by every subject during the first consultation; moreover, further statistical analyses such as a stratification of the results based on demographic variables (e.g., living environment) were not feasible due to the unequal distribution of participants across the living environment categories (i.e., most subjects lived with their family). Lastly, the cross-sectional nature of the study restricts the possibility of establishing causal relationships or tracking longitudinal changes in psychopathological symptoms over time.

In conclusion, this study highlights the high prevalence of ATs in a group of young individuals struggling with mental health concerns. Additionally, subjects exhibiting more ATs displayed an overall greater severity of psychiatric symptoms across various psychopathological domains, including mood, anxiety, EDs, psychotic symptoms, and personality structure. The findings also underscore the necessity of adopting a dimensional approach to psychopathology to better understand the complex interplay of symptoms and facilitate tailored interventions. Future studies with a larger sample, a longitudinal nature, and a control group may provide further insights into the relationship between ATs and other psychiatric disorders.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None.

Competing interest

None.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.