Introduction

Corruption can be considered a multifaceted phenomenon associated with the abuse of authority by a civil servant for personal gain, which has substantial consequences for individuals and society in general (Fascì 2017). It has many forms that combine the concept of illegal benefits, which is the purpose of committing corrupt actions. The term ‘ethics’ refers to a set of moral principles that establish a person’s behaviour, determining what is considered right and wrong in a given social context. It is a criterion for assessing the integrity of individuals and organizations (in the case of corruption, the criterion of legality). Corruption is based on a deliberate violation of the norms of ethical behaviour. By acting corrupt, a person ignores the moral norms established in society, which threatens personal and collective integrity. This leads to undermining trust in the relevant government agencies, organizations, or businesses. According to data for 2023, there is a tendency for corruption to worsen both within the European Union (EU) and in other countries. In cases of stability of this state, citizens of states note that the level of corruption is constantly growing, despite the reports of organizations (Italy, Greece). In other countries, there is a disappointing trend in the attitude of the population to corruption and, in particular, its approval (Latvia) (Transparency International 2023).

Today, the issue of corruption and violation of ethical standards by civil servants is more relevant than ever. After all, every day the level of corruption is growing both in the EU member states and in other countries. Given the various cataclysms and wars that are raging in many states, it is extremely important to preserve the authority of state power and the trust of citizens in it. The growth of corruption demonstrates representatives of the civil service as persons who violate laws, while exercising their powers, which negatively affects the attitude of the population to the government of their state. Corruption has a direct impact on the rule of law, and if the level of corruption is assessed poorly, there may be a problem with ensuring the implementation of this right (a similar situation has developed in Greece).

Zamfirache (Reference Zamfirache2021) investigated the problem of corruption from the standpoint of business ethics. The author identified the negative impact of corruption on the development of the state and noted that corruption hinders economic growth and leads to the loss of investors. Using the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), the researcher determined that in most cases, the level of corruption in the world’s richest countries is usually quite low (in particular, in Denmark, Finland, Sweden, Iceland, Singapore, New Zealand and Canada). Soyaltin-Colella and Cin (Reference Soyaltin-Colella, Cin, Kubbe and Merkle2022) highlight the subject of corruption from the viewpoint of gender inequality in the EU. They argue, from a feminist standpoint, there is a serious problem of corruption in the EU and the lack of good governance, which has led to gender inequality. The researchers draw attention to the importance of equality between women and men and demonstrate the impact of this inequality on corruption in the EU.

Bellingeri and Luppi (Reference Bellingeri and Luppi2024) argue that the new EU Directive to combat corruption contains provisions that do not comply with the principle of proportionality, legality and degree of certainty of crimes (which are necessary to qualify crimes). They stress the importance of international cooperation in the field of criminal law to combat corruption. In particular, they note the need to harmonize offences at the EU level since, otherwise, unequal treatment and an ineffective anti-corruption system may arise. Some researchers focus on more visible, understandable examples to assess anti-corruption efforts in specific areas, such as the banking sector, and the sports sector (Loomis and Loomis Reference Loomis and Loomis2020; Novella-García and Cloquell-Lozano Reference Novella-García and Cloquell-Lozano2021). Separate publications are devoted to the codes of ethics, the impact of business ethics on minimizing corruption in companies, and the psychological process of corruption (Fróes Couto and de Pádua Carrieri Reference Fróes Couto and de Pádua Carrieri2020; Sakarneh Reference Sakarneh2020; Abraham and Pea Reference Abraham and Pea2018).

In general, research on ethics and corruption in the EU, given the content analysis of changing attitudes, is quite limited, despite the relevance of this problem. There are a large number of studies that relate the concepts of ethics and corruption and examine these concepts separately or in general. However, very few studies consider this issue in the context of the European Union, and there are even fewer on specific countries using reports from international organizations. This study’s novelty lies in its distinctive methodology for examining the correlation between ethics and corruption in the European Union, specifically targeting Italy, Greece, and Latvia. This study offers novel insights into the impact of ethics on public perceptions and governance by integrating a comparative investigation of corruption levels via the CPI with ethical considerations. This study provides a novel viewpoint on the significance of ethical conduct in addressing corruption, enhancing both theoretical comprehension and policy formulation.

The purpose of this study is to establish the link between ethics and corruption in the context of the EU and analyse statistical data on the attitude of citizens to corruption in specific states.

The main objectives of this study are to:

-

• define the concept of corruption, its content, and subcategories;

-

• establish a link between ethics and corruption;

-

• perform an analysis of the level of corruption in accordance with the reports of CPI Transparency International;

-

• investigate changes in the level of corruption in Italy, and the attitude of the population to this offence;

-

• analyse the level of corruption in Greece according to CPI reports;

-

• examine the issue of corruption in Latvia;

-

• conduct a comparative analysis of the ethical aspect of corruption in Italy, Greece and Latvia.

Literature Review

‘Corruption’ refers to fraudulent activities conducted by influential persons (persons in power) to obtain certain benefits. In most cases, corruption is used as an auxiliary means of achieving this goal. It mainly applies to situations where more ethical methods of resolving a particular dispute or problem seem inappropriate or inaccessible. Corruption is characterized as a persistent phenomenon and can exist in government agencies or corporations for many years (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2019; Simonyan Reference Simonyan2023).

The fight against corruption is an important element of EU strategy, as corruption contributes to the spread of crime and terrorism. Corruption has a direct impact on such phenomena as the rule of law and ensuring democracy in the state (Sanyal and Samanta Reference Sanyal and Samanta2020). Its consequences extend to all areas of government and business, which, in turn, implies negative economic, legal and social changes. It is considered that the EU is one of the least corrupt areas but, despite this, statistics show that there are a small number of EU countries where the level of corruption is at a minimum level, while most EU member states have a higher level of corruption. According to EU experts, the cost of corruption ranges from €179 to €990 billion per year – up to 6% of the gross domestic product of the European Union (European Commission 2024).

The only international document aimed at combating corruption and binding on EU member states is UNCAC (United Nations Convention Against Corruption). As a supranational organization, the EU ratified the UNCAC in 2008. This convention provides not only for the main aspects of the fight against corruption but also defines the types of offences belonging to the general category ‘corruption’ (European Commission 2021). These types of offences include:

-

• bribery of civil servants, the provision of certain illegal benefits, or the implementation of an offer or promise to provide this benefit to representatives of the civil service. This also includes the requirement or receipt of benefits by a civil servant, in any form, directly or indirectly, to persuade them to take certain actions or decisions that they will conduct in the performance of their official duties;

-

• bribery of foreign civil servants and officials of public international organizations. In this case, the illegal benefit concerns a certain foreign civil servant directly, or another individual or international organization. It means the commission of certain illegal actions on the part of these persons in the performance of their duties, to obtain benefits in conducting international commercial affairs;

-

• misuse of property by a civil servant;

-

• abuse of influence in the field of official activity. This means the use by a civil servant of their influence, to obtain illegal benefits from an administrative or state body. In addition, extortion from a civil servant to use their influence for profit;

-

• abuse of official authority – this consists of encouraging the civil servant, who has opportunities or position, to perform or refuse to perform any action contrary to the law, in the process of exercising their powers;

-

• concealment or retention of property that was obtained illegally;

-

• illegal unjustified enrichment – a substantial increase in the state of a public official, which cannot be properly explained, given their legal income;

-

• bribery in the implementation of economic activities in the private sector, providing illegal benefits (or extortion of its acceptance) to a person working (or managing) in a private sector business entity in order for them to perform a certain action or refrain from committing it;

-

• misappropriation of someone else’s property (funds, securities, things) in the private sector, by a person performing their work there, conducting financial, economic, or commercial activities;

-

• laundering of illegal funds, which involves putting such funds into circulation (stolen or acquired in another illegal way), to hide their origin;

-

• obstruction of justice – giving false testimony, preventing its provision, concealing evidence of an offence, making threats and intimidation, causing bodily harm to persons involved in the offence in a certain way (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2004; Stiernstedt Reference Stiernstedt2019).

This list includes a fairly extensive range of illegal acts that are classified as ‘corruption’ and, in most cases, it involves obtaining illegal benefits. In most cases, the offence is committed due to non-compliance with their duties by civil servants, and employees or managers of various enterprises. This is where the indissoluble link between ethics and corruption manifests itself, as ethics becomes a guiding principle that either fosters or curtails corrupt practices within an organization or society (de Sousa et al. Reference de Sousa, Clemente and Calca2022). Ethics is crucial in promoting honesty and fairness among persons, establishing a distinction between morally acceptable behaviour and corruption. Ethical behaviour fundamentally embodies a dedication to fairness, justice and transparency, acting as a deterrent against corruption. When ethics are neglected, the integrity of individuals and institutions deteriorates, allowing unscrupulous activities to thrive. Corruption constitutes not merely an unlawful conduct but also a significant ethical deficiency, indicative of a wider societal problem of moral deterioration.

Ethics in the area of public administration consists of the fact that civil servants and officials must act in the public interest, manage public resources properly, and make impartial decisions (Wysmułek Reference Wysmułek2019). This behaviour of the employee contributes to improving not only the financial field but also public confidence. In turn, unethical behaviour of public officials (in particular, EU member states) negatively affects both the image of the relevant state and the image of the entire European Union, while reducing confidence in it (European Court of Auditors 2019). Ethical standards erosion results in immoral behaviour, institutionalizing corruption. Compromised ethics erode public trust in political institutions, while the absence of ethical leadership in public offices normalizes corruption, rendering it acceptable to both citizens and officials.

Ethical behaviour has appropriate principles that should guide a civil servant. An important place among these principles is occupied by the principle of impartiality, which provides for the duty of a civil servant to observe the principle of impartial treatment of all citizens, guaranteeing their fair treatment. The next principle is the principle of transparency – all decisions of officials should be documented and publicly available to ensure proper accountability of the authorities to society. In addition, there is the principle of no conflict of interest, which provides for the prohibition of accepting gifts or any benefits that are illegal and are aimed at influencing the actions of an official (The ethics of civil services… 2024). When these ethical values are maintained, they serve as formidable protections against corruption. However, when overlooked, the ethical violation becomes the fundamental source of systemic corruption, resulting in the exploitation of public resources and the deterioration of the public sector.

Thus, ethics is an integral part of such an offence as corruption, in that it ensures the legality or illegality of the actions of a civil servant. An important element of corruption is the economic situation of the state (in particular, the EU), as well as political and cultural components that affect the level of crime in the state and, directly, on the level of corruption (these elements can be both a component of corruption and its consequences) (Remeikiene et al. Reference Remeikiene, Gaspareniene, Fedajev, Raistenskis and Krivins2022; Tseng Reference Tseng2020). Another component of corruption is the subjects – the person who provides or offers illegal benefits and the person who accepts them. It is these two factors that determine the level of corruption in the EU and the fight against it. In the analysis of corruption, it is crucial to acknowledge that both the donor and the recipient actively contribute to the continuation of corrupt activities. The ethical decisions of persons in these positions are crucial for dismantling the cycle of corruption. In the absence of a unified dedication to ethical conduct, corruption persists as a continual issue, both within the EU and beyond.

Materials and Methods

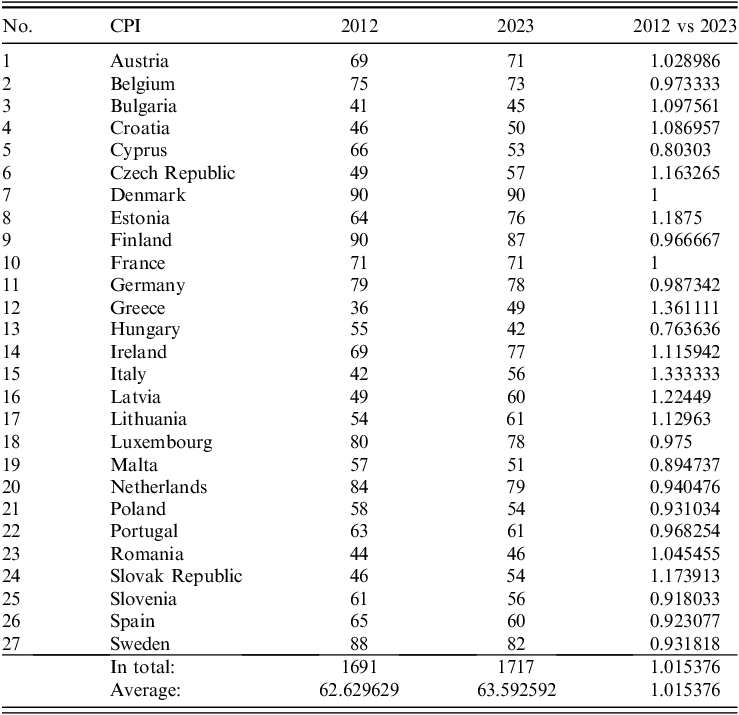

First, the experiences of such states as Italy, Greece and Latvia were used to thoroughly review the issue of ethics and corruption in the EU; in particular, to analyse the perception of corruption. The country data were selected as a result of a summary of Table 1, which contains comparative data obtained from CPI reports on the level of corruption in the EU in 2012 and 2023. This timeframe was chosen as it reflects significant political, economic, and legislative developments in the European Union, particularly in the context of anti-corruption measures and evolving public attitudes toward corruption in Italy, Greece and Latvia. Furthermore, this period allows for the analysis of trends and the impact of specific anti-corruption policies and reforms implemented by the EU and individual states.

Table 1. The table of comparative CPI data

Notes: Column 2 contains a list of EU countries; column 3 – score according to the 2012 CPI; column 4 – score according to the 2023 CPI; and column 5 – indicator of changes in the score from 2012 to 2023.

Source: Compiled by the authors based on Transparency International (2023).

Table 1 shows how much the CPI score increased or decreased, which, in turn, allowed identifying the three countries that achieved the greatest reduction in corruption perception between 2012 and 2023 (Italy, Greece and Latvia), which is why they were chosen for the analysis. During this stage of work, the method of quantitative analysis was used, due to which data on the perception of corruption were collected and divided into separate categories. The annual official reports of Transparency International (2023), a non-governmental international organization for combating corruption, were analysed to obtain these data. In Italy, the report of the Instituto Nazionale di Statistica (Sistema Penale 2024a; 2024b), the European Commission’s anti-corruption report on Italy (Montanari Reference Montanari2014), the report of the Group of States against Corruption (GRECO) (Occhipinti Reference Occhipinti2024); in Greece – the reports of the National Transparency Authority (NTA) (2024); and Latvia – the report of Corruption Prevention and Combating Bureau (2023). These reports provide numerous statistics and qualitative assessments that are important for understanding how corruption is perceived in different countries of the world.

For a more thorough analysis of citizens’ perception of corruption, a qualitative analysis was conducted, in particular, this applies to data from surveys in various reports – Transparency International (2023), European Commission on the fight against corruption (Montanari Reference Montanari2014), and also the EU’s report ‘Eurobarometer’ – Citizens’ attitudes towards corruption in the EU in 2023 (‘Eurobarometer’ survey shows… 2023). The CPI serves as a crucial metric in this analysis, offering a widely acknowledged assessment of corruption in public sectors. The CPI relies on expert evaluations and surveys of business professionals, making it a reliable and objective resource for assessing corruption levels among various nations. This index facilitated an evidence-based examination of corruption trends in Italy, Greece and Latvia, offering a quantitative assessment that reflects both worldwide and EU-specific patterns.

Due to these surveys, the statistics obtained were in-depth, as they reveal the personal experience of the population and their understanding of the problem of corruption in these countries. The use of the comparative method allowed comparing the existing definitions of the concepts of corruption and ethics indicated in studies, dictionaries and internet sources, which helped in establishing a conclusion about this concept. It was also used to compare CPI data and identify countries with the highest and lowest levels of corruption, both among EU member states and in other countries of the world. Since the analysis of the United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC) (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2004) was conducted, which is a normative legal act, a hermeneutical method was used to identify forms of corruption. This method was also used to interpret various forms of corruption defined in UNCAC and studies.

Results

Establishing the Level of Corruption in Accordance with Transparency International Reports

Transparency International is an organization that does an annual assessment of corruption across 180 different countries, offering significant metrics via its CPI. The CPI employs a 100-point scale, with 0 denoting very corrupt nations and 100 signifying countries seen as free from corruption. The CPI offers a comparative analysis of corruption levels among countries, where lower numbers signify greater corruption prevalence. The Transparency International report (2023) indicates that almost two-thirds of countries received scores below 50 points, highlighting a substantial worldwide corruption problem (Teichmann and Falker Reference Teichmann and Falker2020). The worldwide average corruption score is 43, indicating widespread difficulties in governance and public sector integrity. Moreover, a concerning negative trend has emerged in the fight against corruption: in recent years, corruption levels have deteriorated in over 23 nations, indicating a regression in global anti-corruption initiatives. This drop indicates that, despite global initiatives, numerous states are failing to enact effective strategies to combat corruption, hence intensifying its detrimental effects on social and economic growth.

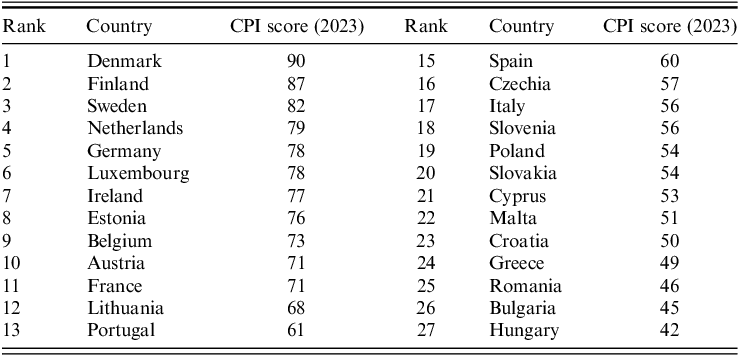

According to the results of the 2023 CPI report, Denmark was recognized as the least corrupt country in the world with an indicator of 90, Finland – 87, and New Zealand – 85. It should be noted that compared with CPI data since 2012, in 2023 the lowest rates for this period were found in Sweden – 82, the Netherlands – 79, Iceland – 72 and the United Kingdom – 71 (Katanich Reference Katanich2024). In particular, this indicates stability in states, the effectiveness of their legislative framework, and implies citizens’ trust in public administration (Munteanu et al. Reference Munteanu, Ileanu, Florea and Aivaz2024) (Table 2).

Table 2. The 2023 CPI report (EU countries).

Source: Compiled by the authors based on Transparency International (2023).

Table 2 shows the average level of corruption in EU member states. Thus, among the countries with the highest rates were Denmark with an indicator of 90, Finland – 87 and Norway – 84, while the countries with the lowest rates were Hungary – 42, Romania – 46 and Bulgaria – 45. Compared with 2012, only six EU countries substantially improved their performance, in particular, the Czech Republic – 57, Estonia – 76, Greece – 49, Latvia – 60, Italy – 56 and Ireland – 77. In relation to the indicators obtained in 2015, the level of corruption in Austria has substantially worsened – 71, also Luxembourg – 78 and Sweden – 82 (Munteanu et al. Reference Munteanu, Ileanu, Florea and Aivaz2024).

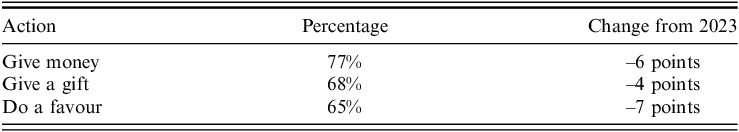

As for the attitude of EU citizens to corruption, the data for this are presented in Table 3. Despite a decline in disapproval for all three actions since 2023, the elevated percentages suggest that the majority of EU citizens continue to vehemently oppose corruption in these manifestations. The minor decrease in disapproval across all categories indicates a potential moderate reduction in the degree of public opposition to these behaviours, although it remains elevated overall. This alteration may signify a changing perspective or the intricacies involved in completely eliminating corruption-related behaviours, notwithstanding citizens’ predominant commitment to rejecting such offences. Nevertheless, the persistent high levels of dissatisfaction about these measures indicate a sustained strong opposition to corruption among the EU population.

Table 3. Disapproval of corruption among EU citizens.

Source: Compiled by the authors based on European Union (2024b).

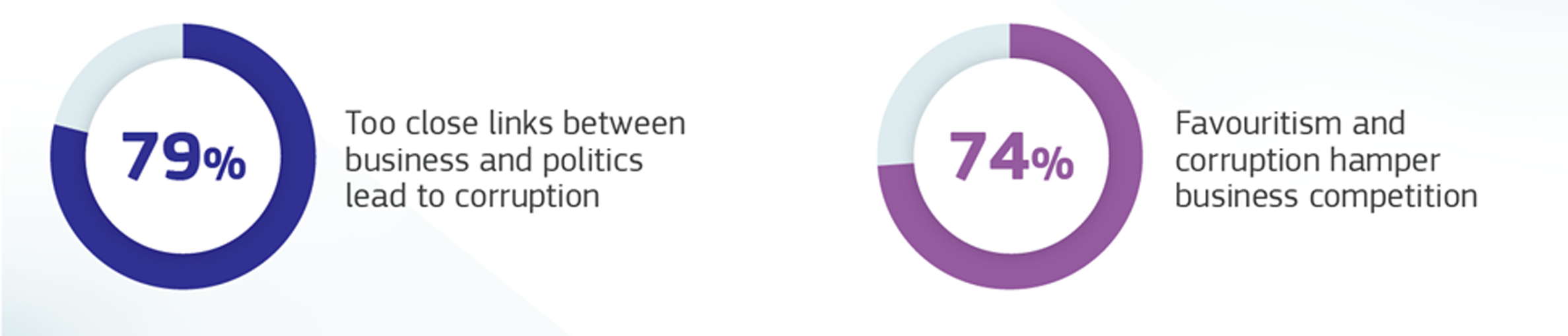

As for business corruption, it was determined that the majority of companies that are located within the EU (79%) noted that business and politics are extremely interconnected, and this is why there is a high risk of corruption. In the EU, 49% of businesses stated that the most common corrupt practice in their countries is to grant privileges to friends or family members in the business sector, while 48% spoke about granting them privileges in public institutions. In particular, a substantial part of these companies (74%) noted the negative impact of corruption and the existence of a trend regarding the privileges of loved ones in the business sector (Figure 1) (European Union 2024a).

According to these data, corruption is a global problem not only for the EU but also for states around the world. In 2023, the average level of corruption among EU countries was 64%, but it should be considered that in one state the indicator could be 90% (Denmark), while the level of corruption in another country, in particular, in Hungary, it is only 42% (European Union 2024a). This, in turn, points to strong differences in the level of corruption in the society of the European Union.

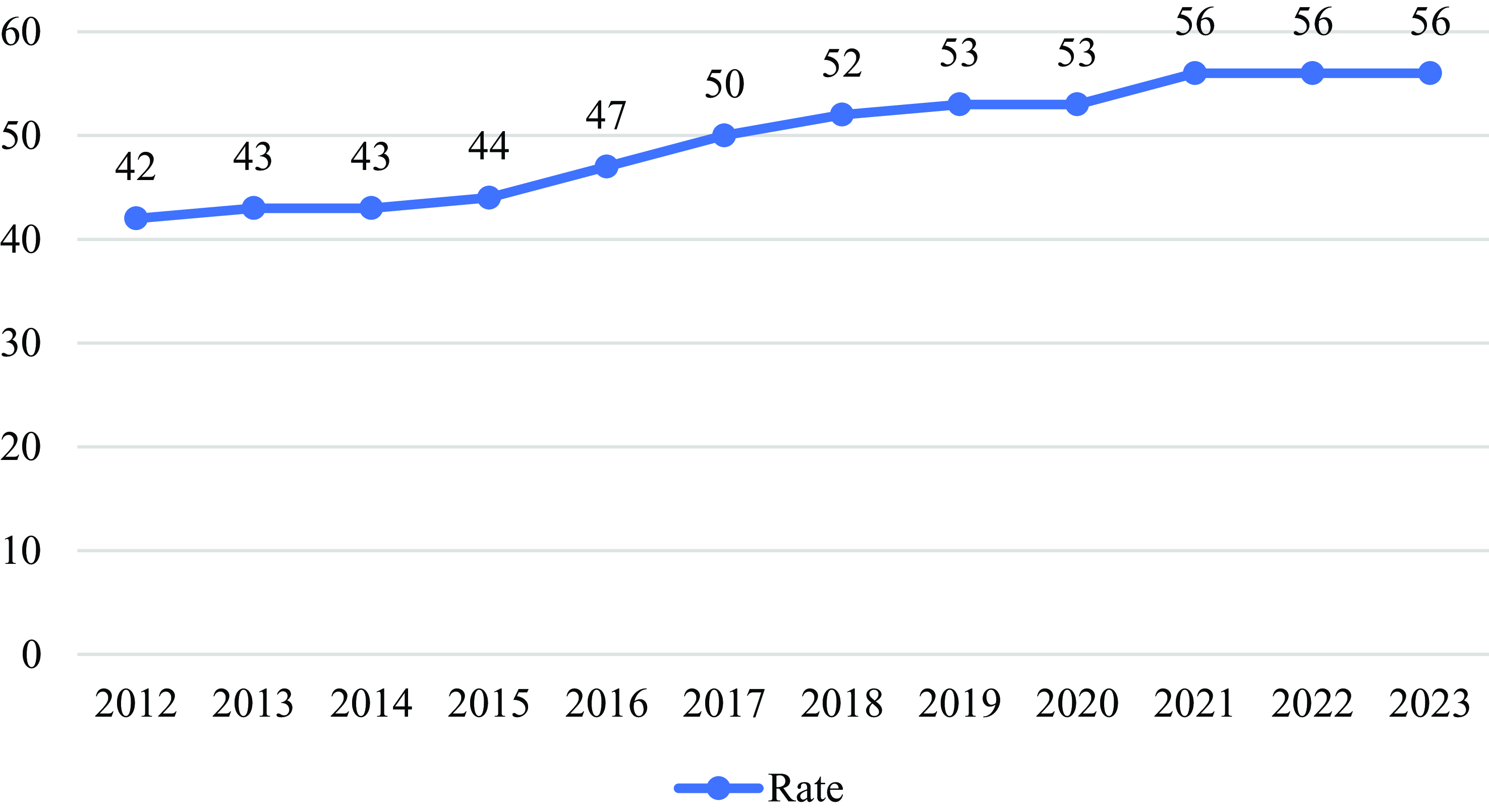

The Level of Corruption in Italy According to Reports from CPI Transparency International and GRECO

A report by Transparency International (2023) indicated that, in 2023, Italy ranked 42nd (out of 180) in the CPI, and the level of corruption in this country was estimated at 56 points, which is substantially better than in 2012 (42 points) (Corruption perception index… 2024). Figure 2 reflects the change in the level of corruption in Italy, starting from 2012 to 2023 according to the CPI, and establishes a positive growth trend of 14 points, which indicates the effectiveness of anti-corruption measures. Thereby, there is a certain stagnation because, in recent years, the improvement in the level of corruption has stopped.

Figure 2. Corruption rate in Italy from 2012 to 2023.

Source: Compiled by the authors based on Corruption perception index, Italy 42nd out of 180 countries (2024).

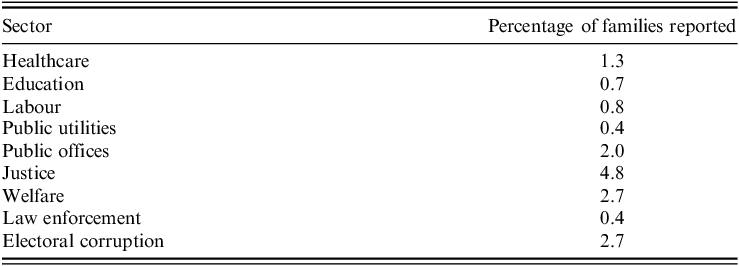

Table 4 is a summary of the documented incidence of corruption across different sectors in Italy. It indicates the proportion of families that have experienced or are cognizant of corruption in areas such as healthcare, education, labour, public utilities, government offices, justice, welfare, law enforcement and electoral procedures.

Table 4. Corruption across sectors in Italy.

Source: Compiled by the authors based on Sistema Penale (2024b).

The table indicates that the healthcare, education, and labour sectors have comparatively lower corruption rates, implying that, although corruption is present, these domains are less impacted by unethical behaviours than others. But the fact that even these areas report some degree of corruption shows how widespread this problem is in Italian society. On the other hand, sectors such as justice and welfare exhibit significantly elevated levels of corruption, indicating a greater susceptibility to the abuse of authority. The justice sector, notably, highlights potential systemic flaws within the legal framework that require attention, including the possibility of bribery or manipulation of legal decisions. The research also indicates alarming levels of tolerance for specific types of wrongdoing. This is especially apparent in the endorsement of electoral bribery by a minor yet notable segment of the population (4.5%). This implies that corruption, especially in political and electoral processes, may be perceived as a pragmatic or even essential component of operating within these institutions by certain persons. This acceptance may provide a substantial obstacle to mitigating corruption, indicating that addressing the issue may necessitate not just legal reforms but also changes in public perceptions on the acceptability of corrupt practices.

The report of the European Commission (2021) on the fight against corruption for 2023 contained data on the attitude of citizens to corruption in Italy. In particular, it was established that a substantial 97% of Italian citizens claimed that corruption is both worldwide and endemic within the nation. This discovery highlights the extensive public recognition of corruption as a major societal concern. Notably, 48% of Italian citizens reported frequently encountering or being personally affected by corruption. This indicates that corruption is regarded not merely as a remote issue but as a quotidian reality for almost half of the populace. It may indicate the normalization of corrupt behaviours within Italian society, where such actions are so entrenched that they frequently manifest in various facets of life, from bureaucratic processes to commercial transactions.

Seventy percent of the population noted a widespread phenomenon of corruption in the field of Public Procurement (this issue is regulated by the regional state bodies) (Montanari Reference Montanari2014). Public procurement, which involves the acquisition of goods and services by the government, is especially susceptible to corrupt practices owing to the substantial financial resources and the discretionary power exercised in contract awards. The perception of rampant corruption in this domain underscores inherent deficiencies in the regulatory and supervision frameworks, which should ideally guarantee openness and equity. The regulatory structure, overseen by regional state authorities, seems inadequate in addressing this issue, indicating possible inefficiencies or deficiencies in enforcement and monitoring that may require immediate reform. In addition, 60% noted an increase in corruption in local authorities (Montanari Reference Montanari2014). Local administrations, typically accountable for essential public services such as education, healthcare and infrastructure, wield significant influence over the daily lives of inhabitants. The increase in corruption inside these entities raises concerns regarding the deterioration of trust in local governance and the possible compromise of public service delivery. The increase in local corruption may be attributed to the fragmentation of political authority, rendering local governments more vulnerable to clientelism, favouritism and political patronage, hence complicating the enforcement of anti-corruption initiatives.

According to the GRECO report on corruption in Italy, it was determined that the Council of Europe is not concerned about the latest changes in Italian legislation on corruption, but is directly concerned with the Nordio Law of 2024. The amendments to this law provide for the abolition of the crime itself, and, accordingly, criminal liability, abuse of authority by a civil servant, and the return of the burden of proof (Sistema Penale 2024a). In this regard, the Council of Europe has predicted the probability of an increase in the risk of corruption among public officials and officials (Occhipinti Reference Occhipinti2024). GRECO also made comments to Italy about the low level of female representation. The current government consists of only 19 women out of 63 members, which is below the 40% recommended by the Council of Europe. The problem of the gender gap also extends to the state police, national guard units, and the financial service, especially at the managerial level (Occhipinti Reference Occhipinti2024; Jageklint Reference Jageklint2020).

It should be noted that every year corruption losses to the Italian economy amount to at least €237 billion. Corruption contributes to an increase in crime, injustice and inequality (Corruption, survey reveals… 2024). Since the CPI indicator decreased from 5.5 to 3.9 in Italy for the period 2001–2011, the damage caused by corruption can be estimated at the amount equal to: about €10 billion per year in terms of the gross domestic product; about €170 per year in terms of per capita income; and more than 6% in terms of labour productivity (Municipality of Massa – Transparent Administration 2015). Thus, corruption has negative consequences not only for citizens but also for the whole state.

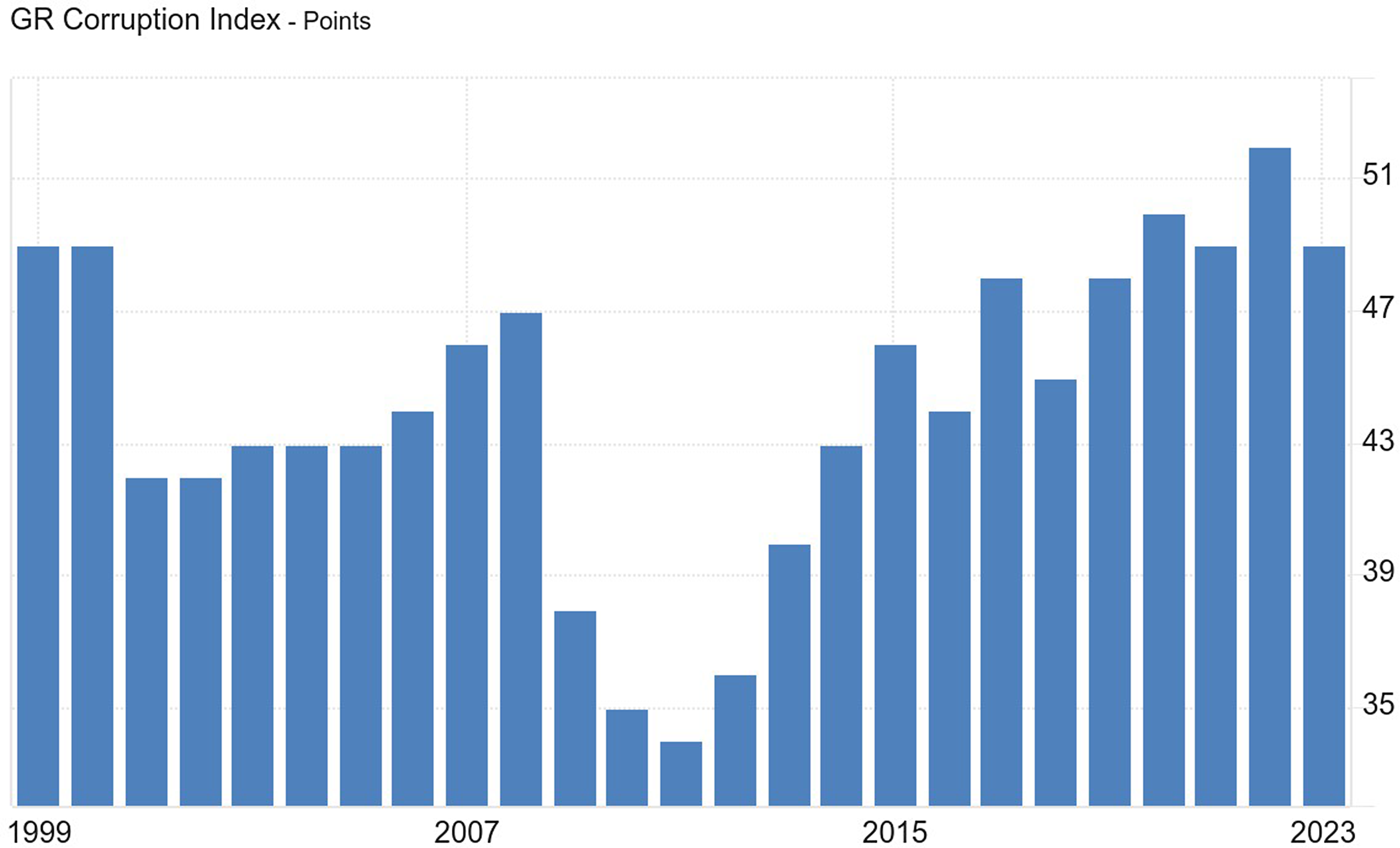

Level of Corruption in Greece According to CPI Transparency International Reports

According to CPI Transparency International (2023), the level of corruption in Greece was estimated at 49 points (three points lower than in 2022). On average, from 1995 to 2023, the level of corruption was estimated at 44.76 points, the maximum score was reached in 1997 – 53.50, while the minimum score was recorded in 2011 – 34 (Trading Economics 2024a). In particular, the situation with the level of corruption in Greece is shown in Figure 3, which contains data from 1999–2023.

In general, comparing the level of corruption from 2012 to 2022, the CPI showed an overall trend towards improvement at this level. However, in 2023, Greece’s indicators underwent a notable deterioration, prompting serious apprehensions regarding the nation’s advancement in combating corruption and maintaining the rule of law. This sharp drop reflects the challenges Greece faces in maintaining and building upon the gains made in prior years. According to Transparency International (2023), as a result of the illegal interception by the Greek government of messages from journalists and opposition politicians, as well as harassment of press freedom and a decrease in the level of independence of the judicial system, the country experienced the largest drop in the level of the rule of law in the EU. In particular, this is owing to excessive government interference in the case of Predatorgate wiretapping, including threats to members of the independent investigative body conducting the case and obstruction of witness protection (Chapter ‘Corruption’… 2024). The consequences of these events are significant, indicating a perilous transformation in Greece’s governing framework. The deterioration of press freedom and judicial independence presents a significant threat to the checks and balances vital for democratic operation. When governments control the media and intimidate judicial institutions, the integrity of the political system is compromised, leading to a loss of public confidence in the justice system’s fairness. The decline in Greece’s rule of law indicators, the most substantial inside the EU, underscores the increasing perception of impunity among the powerful and raises serious concerns regarding domestic stability and Greece’s foreign reputation.

According to the NTA report, the majority of Greek citizens identified the abuse of official positions in public authorities to obtain illegal benefits as the most prevalent form of corruption (EAD: 8 out of… 2022). This observation underscores a significant issue within the nation’s governance framework. This type of corruption erodes the fundamental concepts of equity and justice that underpin democratic society. The perception of this issue as pervasive suggests a fundamental defect in the governance framework, wherein corruption is ingrained in the operations of public authority. The main causes of corruption in Greece are nepotism, lack of effective legal regulation, and excessive customer orientation. Other reasons include the lack of state policy and effective control mechanisms, bureaucracy. According to 71.3% of respondents, the level of corruption in Greece is higher than in other EU member states. This perspective is concerning, as it implies that corruption is not merely a national issue but is regarded as more widespread than in other European Union countries. It indicates a prevalent perception that Greece is not complying with the anti-corruption norms required of EU member states, potentially jeopardizing the nation’s reputation and its capacity to engage effectively in the EU’s decision-making processes. On the other hand, 23.7% had the opposite opinion, which may point to either a more optimistic perspective on the country’s progress or a disconnect from the actual experiences of corruption on the ground.

Thus, the decline in Greece’s CPI indicates a number of global challenges that require prompt and coordinated measures to build confidence in public authorities and improve governance. Ensuring the rule of law, combating nepotism, and effective law enforcement are crucial to reversing the negative trend.

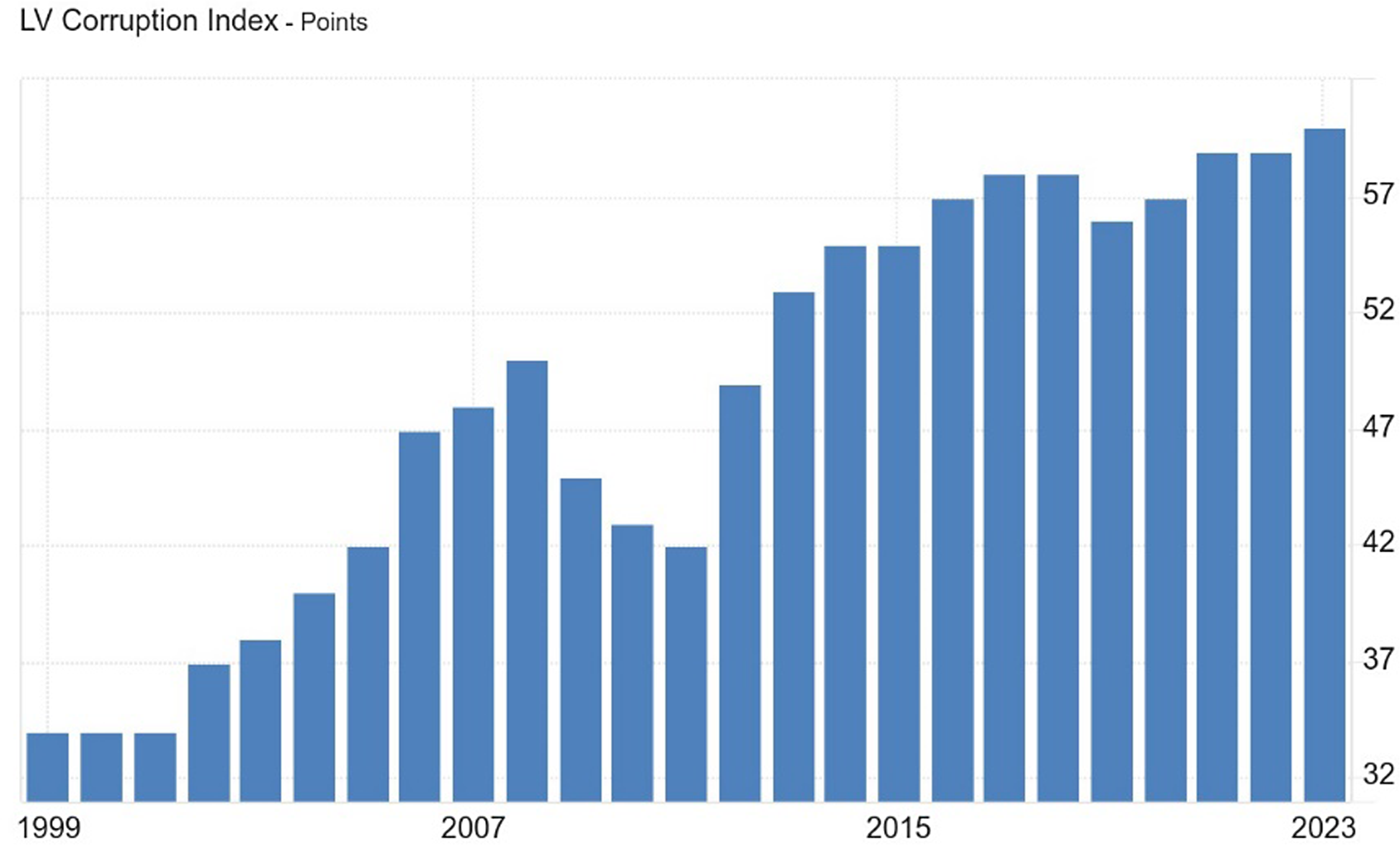

Level of Corruption in Latvia According to CPI Transparency International Reports

According to Transparency International (2023) data, Latvia ranked 36th in the CPI in 2023 with a corruption rate of 60 points. The average level of corruption in Latvia from 1998–2023 was 47.58 points. The maximum score was reached in 2023 – 60, while the minimum score was recorded in 1998 – 27. This is shown in Figure 4, which contains data on the determination of CPI scores for the level of corruption in Latvia (Trading Economics 2024b).

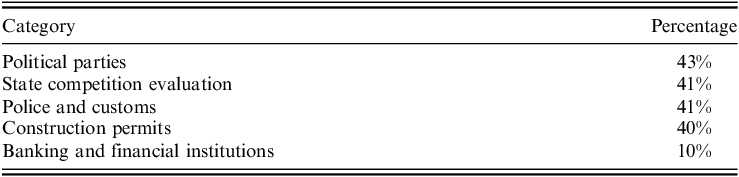

With these data in mind, it can be established that over the past 10 years, the level of corruption in Latvia has substantially improved compared with 1999. However, according to a 2023 Eurobarometer survey, 74% of respondents said that there is a widespread problem with corruption in Latvia, while 27% believed that the level of corruption has only increased over the past three years (despite the CPI rating). Compared with the Eurobarometer data of 2019, the level of perception of corruption in Latvia has decreased by 10%, but the indicator for 2023 remains higher than the EU average. In particular, a 2023 Eurobarometer study determined that during the year, 7% of Latvians were victims of corruption, or witnessed this phenomenon. Four percent of respondents were forced to pay extra, make a valuable gift to a medical professional or a donation to the hospital (‘Eurobarometer’ survey shows… 2023). Despite this, there is a tendency to tolerate corruption among the Latvian population. The survey showed that 49% of people are ready to make a gift to receive public services, 30% – to a certain service, and 23% – to give money. Such a perception of corruption substantially complicates the activities of law enforcement agencies since there is little public support, because society does not perceive corruption as a problem that is subject to priority solutions. Latvian citizens noted that corruption is most common in the field of politics (‘Eurobarometer’ survey shows… 2023). Table 5 provides a clear picture of how Latvian residents view the prevalence of corrupt practices in different areas of public life.

Table 5. Perception of corruption in various sectors in Latvia.

Source: Compiled by the authors based on the ‘Eurobarometer’ survey shows a high tolerance of corruption in Latvia (2023).

The findings suggest that corruption is predominantly linked to political parties, assessments of state competition, and law enforcement and customs agencies, all of which are regarded as having elevated corruption levels. This indicates that these sectors are perceived as especially vulnerable to unlawful activities, likely owing to their crucial involvement in governance, enforcement and the allocation of public contracts and resources. The elevated sense of corruption inside political parties may indicate prevalent apprehensions of political favouritism, clientelism, or the abuse of power for personal advantage. This is a prevalent issue in numerous democracies as political influence is frequently associated with access to public resources, which can be exploited through corrupt tactics. The prevalence of corruption in state competition assessments and law enforcement, including customs, underscores concerns regarding the integrity of essential governmental activities. The prevalent perception of corruption in these regions erodes public confidence in governmental institutions, complicating the ability of authorities to effectively tackle issues such as inefficiency, nepotism, or bribery. The notion of corruption in construction permits highlights concerns with the transparency of urban development and regulatory systems, where bribery or informal arrangements frequently affect decision-making, undermining fairness and the system’s proper functioning.

Conversely, the markedly diminished perception of corruption within banking and financial institutions is notable. Only 10% of the people observes corruption in this area, indicating that financial institutions may be regarded as more transparent and accountable in their activities than other industries. This may signify a comparatively elevated degree of control, oversight, and adherence to norms within the financial sector, or it could suggest a broader confidence in formal financial organizations as being less susceptible to the systemic corruption prevalent in more discretionary public services.

For 2023, the Corruption Prevention and Combating Bureau (2023) identified the most typical criminal offences, in particular, bribery, fraud, abuse of office, money laundering, and embezzlement, for which a penalty was imposed. Compared with 2022, the number of cases of offences related to restrictions on combining positions of civil servants in 2023 increased by 39%, committing actions in a state of conflict of interest by 24%, as well as non-compliance with restrictions on commercial activities by 15%. There was a decrease in offences related to the disposal of state property and finances, as well as the withdrawal of information from databases necessary for the exercise of official powers, and their use in personal interests.

The Latvian government has developed an Anti-Corruption Action Plan for 2023–2025 to strengthen internal control over corruption and reduce the level of tolerance of the population to its manifestations. This plan focuses on the need to encourage public activities and improve the level of knowledge about the available means of reporting cases of corruption (On the 2023-2025 corruption… 2023). In general, the trends of recent years indicate certain difficulties in the fight against corruption in Latvia and the need for more active public involvement and improving the effectiveness of government initiatives.

Comparative Analysis of the Ethical Aspect of Corruption in Italy, Greece and Latvia

Ethical issues are multidimensional since ethical values and principles affect not only the theoretical field but also, above all, practical issues. In particular, these can be real-life situations when it comes to respect for the law and respect for a person, virtue (one cannot abuse your power or position or allow others to abuse them; conflicts of interest should be resolved in favour of the public interest), and justice (not to show favouritism or grant illegal privileges). In the course of this study, it was identified that virtue can be influenced by a person’s material condition. After all, the higher their financial income, the more likely it is that a person will be able to independently provide for their needs (without bribery and other illegal actions) (Megías et al. Reference Megías, de Sousa and Jiménez-Sánchez2023).

Ethics include diligence and responsibility, independence, avoiding conflicts of interest, and efficiency. The ethical aspect also concerns intermediate issues – confidentiality and protection of information, avoiding incompatible external interests, informing about detected violations, attitude to political or public activities, restrictions on receiving gifts, dismissal from work in a state or local government body, and cooperation with former civil servants. Approaches to reducing the perception of corruption in Latvia, Greece and Italy, to some extent, differ. According to Transparency International (2023), in 2023 the indicator of Latvia increased by 11 points compared with 2012 – up to 60 (Trading Economics 2024b). The Latvian national development plan for 2021–2027 provides for measures to improve the fight against corruption and aims to increase the CPI (On the 2023-2025 corruption… 2023). Whereas, in Italy for example, in compliance with the European Central Bank’s guidelines on the ethical framework for the Eurosystem and SSM, the Bank of Italy has created an ethics officer who oversees compliance with ethical standards and reports directly to the bank’s Board of Directors. The functions of the ethics commissioner are performed by the managing director of Internal Audit, who contributes to the definition of ethics guidelines and measures (Bank of Italy 2024). Greece’s score in 2022 increased by 13 points compared with 2012, rising to 49. Greece adopted the first National Anti-Corruption Plan in March 2013–2020. Owing to the institutional changes introduced by law 4622/2019, the National Transparency Authority (2024) updated the 2018–2021 NACAP, making minor amendments to it.

As the experience of Greece shows, codes of ethics should not just be a formality, they should be improved while closing existing gaps, and systematically updated. The formation of ethical standards of performance is inextricably linked with the bringing together of ethical principles, values and norms. It is also important to improve awareness of the illegality of corruption, and various training schemes should be created that will help improve the level of understanding of ethical issues and corruption. In particular, the availability of such training is necessary, primarily, for civil servants (Pliscoff-Varas and Lagos-Machuca Reference Pliscoff-Varas and Lagos-Machuca2021). Even though different groups of employees have their own characteristics in the performance of professional duties, there are several ethical issues that each representative of the public sector faces.

Discussion

The problem of corruption is global in the twenty-first century, it affects all branches of public administration and all spheres of society while creating a split between the population of the state and its ruling elite. It affects the economy of the state, deals a crushing blow to the image of the state in the international arena, and establishes inequality in the rights of citizens. Even though most people argue that the problem of increasing corruption lies solely in inefficient legal regulation by the state, the main problem is directly human ethics. Ultimately, it is the norms of human behaviour (legitimate or illegal) that give rise to corrupt acts, and therefore the main reform of the fight against corruption should begin with a change in a person’s attitude to the phenomenon of corruption.

Thus, de Sousa et al. (Reference de Sousa, Clemente and Calca2022), in their study, stressed the importance of public awareness of the ethical rules of functioning, and the exercise of authority by civil servants. This directly affects the perception of corruption by citizens, which means there is a need to introduce various available sources of information on ethical behaviour in the field of management. The researchers thoroughly examined the possibility of a negative relationship between awareness of basic ethical principles and the corresponding attitude to corruption. A statement in the study by de Sousa et al. (Reference de Sousa, Clemente and Calca2022) is noteworthy, establishing that the older generation, which has extensive experience and faced various situations and learned to distinguish between legitimate and illegal behaviour, turned out to be more tolerant of corruption. In particular, they did not note the substantial impact of corruption on a democratic society. This statement is appropriate for consideration in this study, due to the fact that the opinions of citizens about corruption are completely different. While some categorically deny corruption as a manifestation of disrespect for the law and the principles of impartiality, others believe that by providing illegal benefits, it is possible to facilitate obtaining the service they need. The favourable attitude of the older generation to corruption can be explained by the fact that most of them perceive corruption as an integral part of the system of government.

Krivins (Reference Krivins2021) investigated public procurement issues in Latvia (in particular, using data from surveys). The author determined that in the period from 2012 to 2021, respondents considered the level of corruption in this area to be medium (in 2012 – 33% of respondents; in 2021 – 30.4%). In turn, the number of respondents who claimed a high level of corruption in the procurement sector increased substantially (from 43% to 57.8%). At the time of 2021, 93.1% of respondents indicated the probability of providing illegal benefits to the customer (compared with 2012, this is 12% more). An important result was that the number of respondents who claimed that they were not ready to become a participant in corrupt actions, even if the result was giving an advantage to this subject, increased substantially (from 45% to 64.7%). Notably, the author indicated that there is no link between the perception of corruption in general among the population and between entrepreneurs in the procurement sector. Overall, the study by Krivins contains certain similarities to the results obtained regarding corruption in Latvia between 2012 and 2021 in this study, in particular regarding the analysis of corruption in Latvia over this period of time. Despite certain negative results during this period (an increase in the level of corruption in the field of public procurement), there was a positive trend towards an increase in the number of respondents with a negative attitude to corruption. Compared with this study, in particular data from the period 2021 to 2023, the situation with the level of corruption has improved, but the perception of corruption by the population has changed for the worse.

Drapalova et al. (Reference Drapalova, Mungiu-Pippidi, Palifka and Vrushi2019) investigated the relationship between corruption and democracy. As a result of that study, it was concluded that this relationship is quite close, that these phenomena almost completely depend on each other. Researchers emphasize that when the state of democracy in a country worsens, the level of corruption rises. They explain this by the fact that when the rule of law is deteriorating, state authorities are increasingly moving away from the principle of independence, and the rights of citizens are being restricted. These factors weaken public policy and society, making them vulnerable to corruption. At the same time, when there is a high level of corruption in the state, it is very difficult to build a democratic society. The authors noted that it is necessary to constantly maintain democracy in the state and resort to various measures in the fight against corruption, this will help maintain citizens’ trust in the government of the state. This study repeatedly mentions democracy and the consequences of corruption on democracy. Therefore, Drapalova et al. (Reference Drapalova, Mungiu-Pippidi, Palifka and Vrushi2019) and our study both contain similar conclusions about the importance of fighting corruption. Negative consequences for democracy mean a decrease in human rights, which can lead to conflicts within society. Corruption poses a threat to democracy and human rights and therefore requires the creation of effective public policies at the national and international levels, the establishment of preventive methods, and the direct fight against it.

Fróes Couto and de Pádua Carrieri (Reference Fróes Couto and de Pádua Carrieri2020) in their study considered corruption and ethics in accordance with the views of M. Foucault, and noted the three dimensions of control over the state of corruption – selfishness (a personal interest that can lead to certain corrupt actions), utilitarianism (implies that one needs, first of all, to think about the consequences for the majority of society), and opportunism (using the situation for one’s own purposes). According to this opinion, the code of ethics should correspond to these dimensions only to a certain extent because it will not be able to fully ensure the legitimate conduct of business. The researchers argued that controlling corruption in a neoliberal context can be done through increased surveillance; reducing the attractiveness of illegal benefits; and an increased sense of community. Overall, the study by Fróes Couto and de Pádua Carrieri (Reference Fróes Couto and de Pádua Carrieri2020) considers such factors as ethics and corruption. In particular, the importance lies in the fact that their research supports the opinion that corruption is not completely dependent on ethical behaviour. In addition to the ethical aspect, there may be many other factors that will influence the occurrence of illegal behaviour. They identified the limitations of the code of conduct and stressed the need for specific actions on the part of the state government.

Alva et al. (Reference Alva, Vivas and Urcia2021) demonstrated the relationship between the attitude to unethical behaviour of students in the individual and collective environment and their tolerance for corruption. Although students were mostly negative about inappropriate behaviour, this rejection tended to decrease over time, indicating that the influence of a particular academic environment may affect students’ ethical standards. Whereas Kontogeorga and Papapanagiotou (Reference Kontogeorga and Papapanagiotou2023) showed that changes in the work of higher financial control bodies are necessary to improve the fight against corruption. It is necessary to attract new trends, introduce the latest technologies, and promote the formation of ethical standards to do this, which can substantially increase the efficiency of these bodies. A study by Vilks et al. (Reference Vilks, Kipane and Krivins2024) highlighted the importance of creating an effective legal framework to prevent various types of offences (including corruption).

Comparing the analysis of the findings of the above-mentioned authors with this study, certain general conclusions were formed. In particular, regarding the fact that people’s attitude to corruption in most cases differs, while some argued about the illegality of corruption and its harm, others believed that by providing illegal benefits, they could get the service they needed. The importance of ensuring democracy in the state is notable because it helps in the fight against corruption, ensuring equality of rights and the rule of law (which is an integral component that provides protection against corruption). In addition, there is the fact that the fight against corruption and the factors that protect society from it are not based solely on ethical standards. A comprehensive approach is needed to combat corruption, which will include preventive measures and specific methods of combating it. As for corruption in Latvia, the situation was quite difficult because, despite the increase in the level of the CPI indicator, Latvians did not oppose corruption, many of them consider corruption actions quite acceptable.

As a result of the study, it was concluded that the phenomenon of corruption violates human rights and negatively affects the level of democracy and the rule of law in the state. That is why effective legal regulation of the fight against corruption is so important, since systematic violation of these rights can lead not only to a change in the political regime in the country but also to complete despondency of citizens in their state.

Conclusions

This study enhances the ongoing discourse on corruption by highlighting the significance of ethics in changing public views and affecting the incidence of corruption. The findings emphasize that ethical standards are not only theoretical concepts but essential factors in mitigating unethical behaviour, especially in public administration. The analysis of Italy, Greece and Latvia demonstrates the pervasive nature of corruption within governmental frameworks and underscores the difficulties each nation encounters in addressing this problem. Italy and Greece, while considerably enhancing their Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), persist in contending with corruption in critical sectors, especially inside the judiciary and in law enforcement. However, Latvia presents a paradox: despite an enhancement in its CPI score, the populace’s increased tolerance for corrupt behaviours hinders effective measures against corruption.

The relationship between ethics and corruption is strongly interconnected; in environments where ethical standards are feeble or disregarded, corruption flourishes. Impartiality, transparency, and accountability are essential ethical values for promoting equitable governance and mitigating unethical activities. This study emphasizes that corruption is not merely a legal concern but also an ethical dilemma, because systemic ethical deficiencies sustain corrupt practices throughout institutions. Enhancing ethical frameworks in both public and commercial sectors is crucial for effectively addressing corruption.

In conclusion, combating corruption demands more than mere legal enforcement; it requires a comprehensive societal transformation towards ethical conduct across all tiers of administration. This entails the implementation of enhanced ethical training for public officials, the assurance of transparency, and the cultivation of a culture of integrity. The study’s findings indicate that anti-corruption initiatives should be comprehensive, integrating legal, ethical, and societal reforms to achieve enduring advancement. Subsequent studies could broaden this analysis to encompass more EU member states and non-EU nations to ascertain successful worldwide anti-corruption initiatives.

This study can make a substantial contribution to further research, as it contains not only an analysis of the relationship between ethics and corruption but also an analysis of reports on the level of corruption in EU countries. Prospects for further research are to analyse the experience of more countries, in particular, those that go beyond the EU, such as the United Kingdom (considering its past membership in the EU). This includes the countries with the highest and lowest levels of corruption – Denmark and Somalia, respectively – this will help to establish differences between anti-corruption methods and establish the most effective ones.

Availability of Data and Materials

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available.

Author Contributions

The authors’ contributions are equal.

Consent to Participate

The study was conducted without human participation. Informed consent is not required.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare they have no financial and competing interests.

Ethical Approval

The study was conducted without human participation. Ethical approval is not required.

About the Authors

Anatolis Krivins is a PhD, Associate Professor at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at the Daugavpils University. Research interests include: corruption, people’s behaviour.

Esat Durguti is a PhD, Associate Professor at the Faculty of Economics at the University ‘Isa Boletini’ Mitrovica. Research interests include: ethical principles and the line of legality.

Andrejs Vilks is a PhD, Professor at the Faculty of Social Sciences at the Riga Stradins University. Research interests include: illegal benefits, effectiveness of the government.

Aldona Kipane is a PhD, Associate Professor at the Faculty of Social Sciences at the Riga Stradins University. Research interests include: corruption and ethics, their concept and content.