Introduction

Higher education plays important roles in producing citizens of character and skills necessary for democracy to work. The failure of higher education would mean the failure of the entire society. To play its roles well, higher education needs institutional autonomy and academic freedom, which are under threat everywhere (Hao Reference Hao2020b).

Institutional autonomy and academic freedom go hand in hand. In order to better fulfil the mission of the university, faculty and students need academic freedom. In order to have academic freedom, the institution needs to have autonomy. Academic freedom is thus embedded in institutional autonomy, but it can be weakly embedded, as in Latin America, which is ‘strong in corporate prerogatives for the university as an organization but weak at its core: academic freedom’ (Bernasconi Reference Bernasconi2023). For example, the institution has the right to self-determine its bylaws and regulations and the freedom to develop its own patrimony (Bernasconi Reference Bernasconi2021: 60). But the bylaws can impede academic freedom, and funding can be against non-popular research. Historically, ‘autonomous Oxford and Cambridge in the early nineteenth century denied academic freedom to their faculty, whereas nonautonomous Berlin University became known for its Lehrfreiheit, or academic freedom’ (Berdahl et al. Reference Berdahl, Altbach, Gumport, Altbach, Berdahl and Gumport2005: 6; see also Cain Reference Cain2023: 4, and Taiwo Reference Taiwo2011: 70 for a similar point). Besides, not everything in the multifaceted ideal that comprises institutional autonomy is closely or directly related to academic freedom, as we will discuss below.

Indeed, institutional autonomy without academic freedom will only become authoritarian management. It must include shared governance for the purpose of academic freedom, or it will easily lead to managerial tyranny (Pringle and Woodman Reference Pringle and Woodman2022: 4). Academic freedom needs to be at the centre of institutional autonomy. And the two terms are not necessarily synonymous, but they cannot be separated in meaning (Bernasconi Reference Bernasconi2021: 60; Bernasconi Reference Bernasconi2023; Nokkala and Bladh Reference Nokkala and Bladh2014: 3−4, 16−17; Taiwo Reference Taiwo2011: 68−69).

In the following, I will define academic freedom and institutional autonomy and delineate the continuum of university autonomy as ‘little or no’, ‘low’, ‘somewhat balanced’, or ‘balanced’. Then I will discuss how the government affects institutional autonomy and academic freedom. My conclusion is that the government plays a key role in the kind of autonomy a university enjoys, and a balanced institutional autonomy requires that actors work together in a federation to protect academic freedom and to better fulfil the mission of the university.

Defining Academic Freedom and Institutional Autonomy

While academic freedom can benefit both the institution and the faculty (Taiwo Reference Taiwo2011: 68), I would rather define the freedom of the former as institutional autonomy and the freedom of the latter as academic freedom just for the convenience of analysis. According to the American Association of University Professors’ (AAUP) 1915 Declaration of Principles on Academic Freedom and Academic Tenure, academic freedom ‘comprises three elements: freedom of inquiry and research; freedom of teaching within the university or college; and freedom of extramural utterance and action’ (AAUP 2001: 292). This definition covers research, teaching and service, the usual roles of a university professor. In other words, professors are free to do research and publish their results, free to discuss subject matter in the classroom and free ‘to write and speak as citizens without institutional censorship or unwanted sanction’ (Hao Reference Hao2020a: 49; see also similar definitions of academic freedom in the 2020 Rome Communique cited in Pruvot et al. Reference Pruvot, Estermann and Popkhadze2023: 83).

Institutional autonomy, or university autonomy, refers to the ability of the institution to make independent decisions regarding its mission and to access the means to accomplish that mission. The European University Association (EUA) identifies four dimensions of university autonomy: (1) organizational autonomy, including academic and administrative structures, leadership and governance; (2) financial autonomy, including the ability to raise funds, own buildings, borrow money and set tuition fees; (3) staffing autonomy, including the ability to recruit independently, promote and develop academic and non-academic staff; and (4) academic autonomy, including study fields, student numbers, student selection as well as the structure and content of degrees (Pruvot et al. Reference Pruvot, Estermann and Popkhadze2023: 9; see also Rayevnyeva et al. Reference Rayevnyeva, Aksonova and Ostapenko2018: 73−74 about the related categories of the EUA’s Lisbon Declaration). Other definitions of institutional autonomy also deal with similar aspects, i.e., internal management structures and policies (organizational), control over material resources (financial), the appointment, promotion and disciplining of staff at all levels (staffing), and student admissions, curriculum, and methods of teaching and assessment (academic) (Taiwo Reference Taiwo2011: 68).

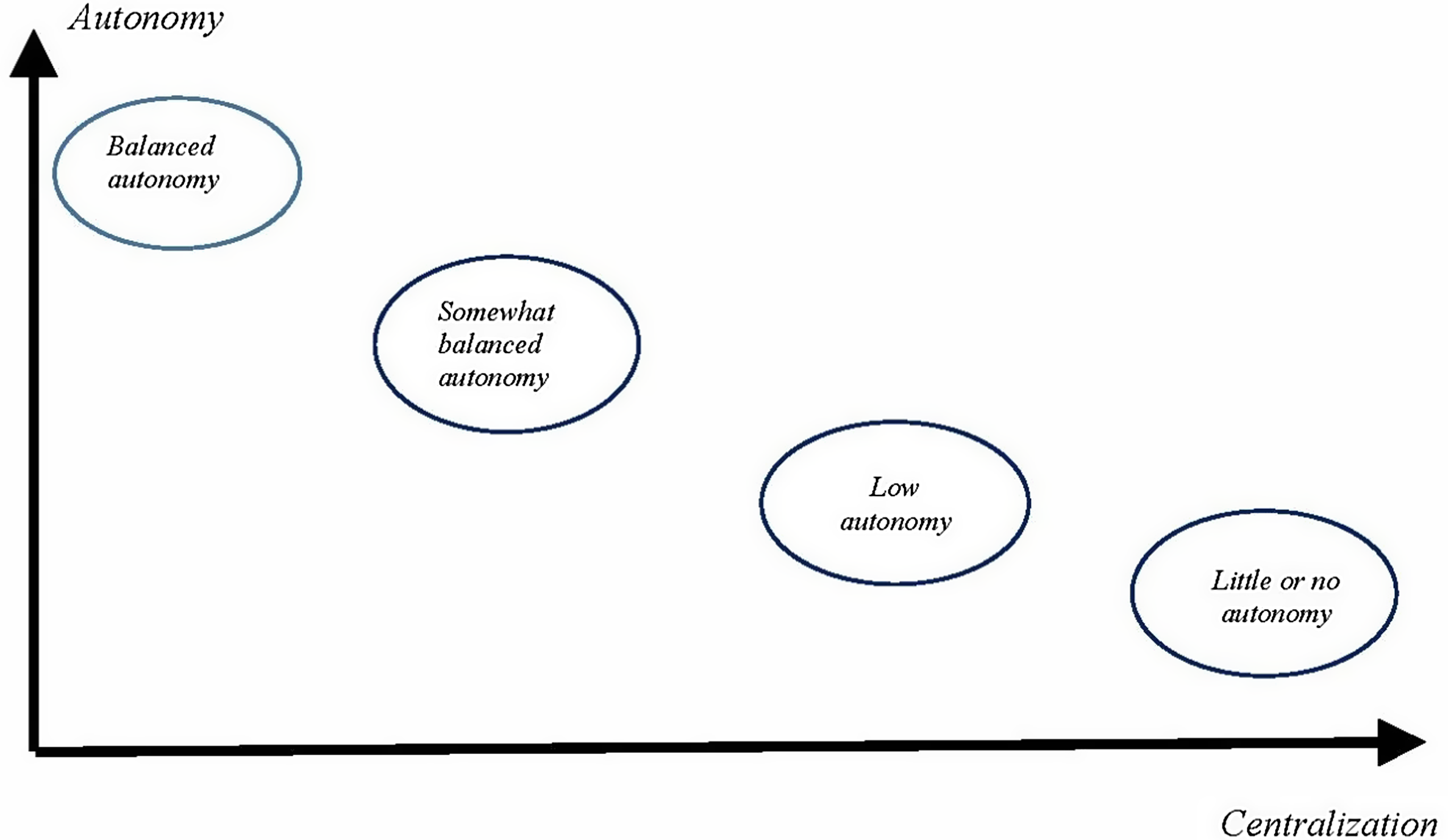

The EUA dimensions of institutional autonomy are a very comprehensive mechanism to gauge the extent to which a university can be free to do (procedural autonomy) what it wants to do (substantive autonomy) to accomplish its mission (Berdahl et al. Reference Berdahl, Altbach, Gumport, Altbach, Berdahl and Gumport2005: 5−6; Lackner Reference Lackner2023: 4; Maassen et al. Reference Maassen, Gornitzka and Fumasoli2017: 241; see also Nokkala and Bladh Reference Nokkala and Bladh2014 for a description of the situation in these terms in the Nordic context). Based on those dimensions, the EUA is able to come up with a scorecard demonstrating the status of each of the 35 European universities and colleges on each of the dimensions, i.e., high autonomy (scoring between 100% and 81%), medium high autonomy (scoring between 80% and 61%), medium-low autonomy (scoring between 60% and 41%) and low autonomy (scoring between 40% and 0%). This is indeed a very worthwhile exercise to help people understand institutional autonomy and for each university and college to know where they stand and where they are still lacking as well as what they need to do to catch up (for an analysis of the Nordic countries using the four dimensions, see Nokkala and Bladh Reference Nokkala and Bladh2014). I would like to do a related but, in some ways, different exercise that covers more educational jurisdictions than Europe and America. I will characterize institutional autonomy in relation to academic freedom as a continuum (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Institutional autonomy versus centralization.

McGuinness (Reference McGuinness, Altbach, Berdahl and Gumport2005: 199−200, 212) and Rayevnyeva et al. (Reference Rayevnyeva, Aksonova and Ostapenko2018: 75−76) both discussed continuums of university autonomy. Mine is different from theirs in that I am expanding the influencing factors to go beyond just the state, and my categories are also different from theirs. McGuinness’s categories include high and low levels of state control, and Rayevnyeva et al. discussed a model that includes minimal autonomy, semi-autonomy (average low), semi-dependence (average high) and independence (maximum autonomy). They also cited other scholars’ model of minimal, partial and complete autonomies. My model of analysis is inspired by other people’s research, but it is different from theirs as well.

In my model of analysis, the categories of little or no autonomy, low autonomy, somewhat-balanced autonomy, and balanced autonomy are ideal types, an analytical construct that helps us understand various scenarios of autonomy but does not necessarily mean ideal or desirable in a normative sense. ‘An ideal type is constructed by the abstraction and combination of an indefinite number of elements which, although found in reality, are rarely or never discovered in this specific form’ (Giddens Reference Giddens1971: 141, referring to Max Weber’s method of analysis). For example, we define China as a case of little or no autonomy, but it does not mean that it does not exhibit characteristics of the other three types at times and in some respects. The same applies to countries or sub-countries we describe in these other types.

This typology is based on the degree of concentration of power, ranging from centralization to decentralization on a continuum from high to low, and resulting in a continuum of autonomy from low to high. That is, the higher the concentration of power, the lower the autonomy, and vice versa. This typology does not put nations or sub-nations into straitjackets. The elements in the types only help us understand the dominant aspects of each type.

Furthermore, one can certainly designate balanced autonomy as high autonomy as long as it has the same explanatory or theoretical power of analysis. However, in reality, if autonomy is not balanced, i.e., if some actor(s) has/have very high autonomy, meaning some monopoly of power, while others do not, it can easily lead to autocracy, no matter whether it refers to the management or the faculty (see examples below). That is why ‘balanced autonomy’ rather than ‘high autonomy’ is used to mitigate confusion. I will now explain each type of autonomy.

Little or No Autonomy

Borrowing Clark’s (Reference Clark2008: 478) rendition, this is where ‘national [or subnational] rules are applied across the system by one or more national bureaus’. The major characteristics of such systems include a nationalized system of finance (emphasis mine, ditto below, to relate to the EUA dimensions of autonomy); ‘much nationalization of the curriculum, with common mandated courses in centrally approved fields of study’; a nationalized degree structure with degrees awarded by the national system; a nationalized personnel system with all those working in the university being members of the civil service; and a nationalized system of admissions with federal rules determining ‘student access as well as rights and privileges’. This happened at one time or another in France, Germany and Italy, but especially in ‘communist-controlled state administrations, such as East Germany and Poland’. This happens where there is a monopoly of power. It doesn’t matter whether it is a monopoly of students, as in some medieval Italian universities; of senior faculty, as in some Continental and English universities in the past two centuries; of trustees, as in some early and not-so-early American colleges; or of autocratic presidents, as in some American institutions (Clark Reference Clark2008: 483).

The strongest contemporary case of little or no autonomy in higher education is probably China. I will give more examples later, but for now suffice it to say that the Chinese government has been building college and university textbooks in humanities and social sciences that must incorporate and be guided by Marxism with Chinese characteristics. Called Ma gongcheng, or ‘Marxism project’, textbooks are compiled, edited and published by the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (MOE 2022). College and university professors are required to use them rather than any other textbooks they might want to choose themselves. The purpose of higher education is to train talents for the Party-state so the Party must control the textbooks, the MOE says.

This is what Clark aptly calls the nationalization of the curriculum, and it is a hallmark example of little or no autonomy on the part of the university and its faculty. This happens especially when the university is an arm of the state in its true meaning and professors are mouthpieces of the government (see also Schoorman and Gatens Reference Schoorman and Gatens2023: 7 on a similar scene in the US).

This also happened in Russia when universities were expressing their support for Vladmir Putin and his re-election campaign (The Barents Observer 2024). Academics in Russia now have to report to authorities about any foreign trips under agreements, contracts, or grants (A UWN Reporter 2024; for more examples of Russian academics’ loss of autonomy, see also Yudkevich Reference Yudkevich2024). And this little- or no-autonomy model of Chinese higher education includes not only the nationalization of the curriculum, but also of financing, staffing and organization, which I will discuss later. China’s academics are also strictly restricted in their contacts with foreign scholars. China’s low Academic Freedom Index (AFI) ranking of 142nd out of 152 countries is an indication of its having little or no university autonomy (Greenfield Reference Greenfield2023; see also V-Dem Institute 2023). Centralization is the key.

Low Autonomy

Low autonomy is when there is a fair amount of systemic differentiation that can defend the institution from outside attacks to a great extent, but not enough of it for them to avoid suffering from certain restrictions. Florida is a good example. The government controls both the state university system’s board of governors and each university’s board of trustees by appointing the majority of their members. The boards’ tendency is to ‘follow the lead of the [state] governor and his allies in the legislative supermajority’ (AAUP 2023: 21). The board of trustees makes decisions such as cutting gender-studies programmes, prohibiting the teaching of Critical Race Theory and eliminating sociology as a core course requirement option. But those are actually government policies, and the boards are merely implementing them. Indeed, the law says that faculty cannot teach identity politics and systemic racism, sexism, oppression and privilege as being inherent in the institutions of the US (AAUP 2023: 34; Nelson Reference Nelson2024). The Trump administration is now implementing some or all of these Florida policies and more on a national scale, and has cut or threatened to cut federal funding if colleges and universities do not obey.

In such cases, the university may seem to have institutional autonomy, but faculty’s academic freedom is strictly limited. The same applies to university presidential appointments of conservative politicians with little academic experience (AAUP 2023: 22). In Florida, academic freedom is violated when students are allowed to record professors’ teaching in class without their consent, just as in China, and even to ask professors to fill out surveys about their political views (AAUP 2023: 31; Greenfield Reference Greenfield2023). And ‘faculty are required to give equal time to ideas in class that are not factually sound or supported by evidence’ according to anti-shielding laws in Florida (Greenfield Reference Greenfield2023).

When Brazil’s Bolsonaro administration (2019−2023) cut federal funding for humanities and social sciences and interfered in rector appointments in universities, the latter was experiencing low autonomy (Bernasconi Reference Bernasconi2023). So was the case of Mexico, which has an AFI score 0.67 out of 1.00, when the government cut research funding and fired two professors supporting student protests (Greenfield Reference Greenfield2023). Universities have low autonomy when that autonomy does not protect academic freedom.

In contrast to the faculty in little- or no-autonomy institutions, the faculty in low-autonomy institutions still have much of their freedom since, arguably, most of the restrictions above mainly create a climate of fear (see AAUP 2023: 35) or (self-)censorship. They can still largely decide what to teach and how to teach it. And they have recourse when such freedoms are violated. For example, in 2021 the University of Florida administration barred faculty members from testifying as expert witnesses on behalf of plaintiffs seeking to block Florida’s voter suppression law. Some of these professors filed suit challenging the university’s conflict-of-interests policy and won. In addition, the judge ‘described the university’s actions as an example of vorauseilender Gehorsam (‘pre-emptive subservience’) in anticipation of “perceived pressure from Florida’s political leaders”’ (AAUP 2023: 30). Some of Bolsonaro’s most far-fetched encroachments were also blocked in a court of law (Bernasconi Reference Bernasconi2023). That is not possible in China’s little or no autonomy institutions.

Other organizations can also come to their aid even if unionization in the public school systems in Florida is met with obstacles set up by the government, such as the method of paying dues and a percentage of dues-paying members required to qualify for union recognition (AAUP 2023: 39−40). The AAUP investigation report I am citing here is one example. Various lawsuits have now been filed by professional organizations againt the Trump administration’s attack on higher education. Such manoeuvring room, however, is not available in states such as China. That is also a difference between democracy and autocracy. But the climate of fear and censorship does relegate Florida’s public education system to low autonomy in relation to academic freedom even though the faculty have some recourse to address the problems, recourse that is not available in places such as China.

In brief, low-autonomy institutions still have some autonomy and freedom, albeit greatly eroded. Some other states in the US, with mostly Republican-controlled legislatures, have similar restrictions on what can and cannot be taught, a similar erosion of shared governance, and similar boards of trustees doing the bidding of the politicians that appointed them. These states include Texas, Georgia and North Carolina, according to an AAUP survey (Greenfield Reference Greenfield2023), as well as Oklahoma, Idaho, North Dakota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Kansas and other red states (Ruth Reference Ruth2023). They may all be considered to be in or adjacent to the low-autonomy group, depending on how seriously academic freedom is violated.

Somewhat-balanced Autonomy

I mentioned nineteenth-century Germany, when the university was an arm of the state and professors were civil servants expected to support the government. But ‘German academics ran their universities, making all the personnel decisions and electing deans and other administrators from among their number’ (Schrecker Reference Schrecker2010: 11). They were restricted in their off-campus activities and could be fired for backing oppositional parties, but most did not mind such restrictions. This was somewhat-balanced autonomy, with the government and the university each having some kind of power and with academic freedom largely guaranteed, although it was not the most desirable kind, i.e., a truly balanced autonomy. I will provide contemporary examples of somewhat-balanced autonomy in the next main section. Somewhat-balanced autonomy, between low autonomy and balanced autonomy, is what most if not all the institutions in mature democracies have in common.

Balanced Autonomy

The desirable ideal typical balanced autonomy may be something similar to what Clark (Reference Clark2008: 247) calls federalism, where decentralization is the key. He says that the complex university tends to be a ‘federal system: semiautonomous departments and professional schools, chairs and faculties, act like small sovereign states as they pursue distinctive self-interests and stand over against the authority of the whole.’ Clark here views the whole educational system as a federation, including government agencies or departments, university systems’ governing boards, accreditation agencies, donors, university boards of trustees, the president, the faculty, students and their parents, as well as the general public, including the media (see Cain Reference Cain2023 for the importance of accreditation). As Clark (Reference Clark2008: 250) says, different groups tend to go their own way, but they also need to perforce seek ‘the benefits of association’. So ‘near-monopolies of power are restricted and a diffusion of power promoted’. By logic, when freedom of research, teaching and study ‘are seriously curtailed, the system as a whole suffers’.

So, in an ideal typical balanced autonomy, no one has a monopoly of power, and each part of the federation strives for its own interest but, at the same time, reaches compromises with other parties so that the interest of the whole can be preserved. These different parties are the different actors I mentioned above. But because of space restrictions for this article, I will discuss mainly the role of the government, although I will inevitably have to mention other actors. Whether the powers are balanced determines whether there is balanced autonomy and academic freedom. Balanced autonomy is desirable and still needs to be strived for.

How the Government Affects Institutional Autonomy and Academic Freedom

The government I discuss here includes state policymakers, state coordinating boards, the courts, legislators and the governors (for these and other actors of influence discussed here, see Kerr Reference Kerr and Brint2002: 13−14) even though the roles of the trustees, the president, the faculty and students are also important. I will now discuss the government’s role in the various scenarios of autonomy.

In Little- or No-autonomy Institutions

Regarding the government’s role in the little- or no-autonomy institutions, China again is the most conspicuous example. There, the role of the government is paramount, and power is monopolized by the Party. I have already mentioned the central imposition of Chinese Marxism in every course curriculum possible. For another example, every university has to have a Party committee that controls the political and ideological orientation of the university’s organization, financing, staffing and academic affairs. Elsewhere, I discussed the Party’s organizational and ideological control of students both in and outside class (Hao Reference Hao2024). I also discussed the seven topics that are taboo in the classroom: civil society, civil rights, universal values, legal independence, press freedom, the bourgeois class with money and power, and the historical wrongs of the Party – often called ‘the Seven Nos’ (Hao Reference Hao2024: 96, 100; see also Pringle and Woodman Reference Pringle and Woodman2022: 4 for more such restrictions). Likewise, in Nigeria, universities cannot decide which courses to offer, who is to teach them, and what research will be conducted. Only the state can (Taiwo Reference Taiwo2011: 72−73).

In China, cameras are installed in the classrooms so that both faculty and students will behave. Recent university charter changes have ditched words such as shared governance and dictated that the university adhere to the Party’s leadership in every aspect of university life, follow Party lines and serve the CCP (Chinese Communist Party) and socialism with Chinese characteristics. Faculty members have to do research on topics that the Party likes and teach the way the Party wants them to teach in order to be promoted or otherwise rewarded, or they will be penalized by being admonished, fired, or even imprisoned (Hao Reference Hao2024: 98−100, 103−104; for the Chinese case see also Douglass Reference Douglass2023; Wilson Reference Wilson2021).

We are seeing authoritarian leaders take similar draconian steps to restrict academic freedom in Turkey, Hungary and India (AAUP 2023: 51−52). Parson and Steele (Reference Parson and Steele2019) studied the case of Hungary where the leaders would stop funding for gender studies and allow publishing only research that supports the government. Another example is the ‘summary expulsion of university professors and lecturers for being critical of government educational policies and other national issues’ in Nigeria and some other African countries (Taiwo Reference Taiwo2011: 71, 73−77; see also Kigotho Reference Kigotho2024 for more on the African situation). Self-censorship is thus also a common practice, just as in China. But the dismissed professors and lecturers in Nigeria were reinstated by the Nigerian Supreme Court, so that may actually put Nigeria into the low-autonomy category below, except when the court injunctions are also ignored by the government. Turkey, Russia, Hungary, Iran, etc., all follow the same pattern of autocracy in higher education (Douglass Reference Douglass2023; for the story of Russia and re-Sovietization, see Chirikov Reference Chirikov2023). Under authoritarianism, whether in China or elsewhere, institutional autonomy and academic freedom have a difficult time surviving, let alone thriving (see also Dreiling and Garcia-Caro Reference Dreiling and Garcia-Caro2022).

In Low-autonomy Institutions

If the government control of higher education is nearly total in little- or no-autonomy institutions, government restrictions in the low-autonomy institutions are less so. In our discussion above, we have already seen how Florida’s governor, legislature and the courts have affected institutional autonomy and academic freedom. The government’s main control is through legislative measures and appointments of trustees that follow their ideology. In 2022 alone, of all the bills that became law, ‘57 percent targeted higher education, compared with just 25 percent of the new laws’ in 2021 (Ruth Reference Ruth2023). Florida’s Senate Bill 266 directly prohibits using state or federal funding to promote, support, or maintain any programmes or activities related to Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) (see Suarez Reference Suarez2024 for the Board of Governors’ vote to implement the policy on 24 January 2024). It also gives the board of trustees and the governor ‘more power in hiring and in termination of appointments and erodes tenure protections’ (Ruth Reference Ruth2023). The University of Wisconsin system has stopped diversity hires and other diversity initiatives after lawmakers threatened faculty’s salary raises and other funding (AP News Reference AP2023). Utah legislators have passed law to ban DEI programmes at schools and in government (Riess and Croft Reference Riess and Croft2024).

Courts are not always friendly to university autonomy and academic freedom. Both the US Supreme Court’s decision to cut off fair share fees for collective bargaining and a federal appeals court’s decision to uphold Texas’ campus gun-carry law hurt institutional autonomy and academic freedom (Hao Reference Hao2020b: 21−22). But whatever the courts’ decision, they are an important check and balance in addition to other organizations, as discussed earlier, in the power struggle between different actors in influencing institutional autonomy and academic freedom.

In Somewhat-balanced Autonomy Institutions

In somewhat-balanced autonomy, not yet the desirable ideal typical one, the government’s interference and involvement in university affairs vary from time to time and place to place (see also Bok Reference Bok2013: 63−69). There are fewer extreme cases of violations although serious ones do happen. For example, government austerity or other financial measures are often used to dictate programme changes, selective research funding, faculty tenure, student intake and university closures or mergers, as in Japan, South Korea, Australia and Africa (Hao Reference Hao2020b: 21; Taiwo Reference Taiwo2011: 70). The Japanese government’s requirement for humanities and social sciences to either abolish themselves or make themselves useful and the South Korean government’s requirement to cut humanities and social science student enrolment numbers and increase the number of STEM students, are just two examples.

In the US in the 1980s, Congress passed laws to start what people later termed as the commercialization of higher education: allowing universities to retain intellectual property rights or to assign them to others, encouraging university technology transfer, and facilitating collaboration with industry (Powell and Owen-Smith Reference Powell, Owen-Smith and Brint2002: 115−116). As a result, industry funding has increased while government funding has shrunk (Washburn Reference Washburn2005: 8−9). For example, in the early 2000s, ‘California supplied just 34 percent of its overall budget, compared with 50 percent just twelve years earlier. Other public universities have suffered similar cutbacks’ (Washburn Reference Washburn2005: 8). Meanwhile, universities increased their research and development budget from industry by an average of 7% but often by double digits: in early 2002, Duke University drew 31% of its R&D budget from industry (Washburn Reference Washburn2005, p. 139).

UC Berkeley’s newest numbers show that, in the past 30 years, state support of its revenue declined from 50% to 14%, while student tuition and fees grew from 18% to 34% in the past decade alone (UC Berkeley Office of the Chief Financial Officer 2023). By the early 2000s, the federal government had already provided ‘less than 15% of all college and university revenues’, although in direct aid to students and funds for research and development ‘federal outlays far exceed those of the states, industry, and other donors’ (Gladieux et al. Reference Gladieux, King, Corrigan, Altbach, Berdahl and Gumport2005: 163; see Bok Reference Bok2013: 65−66 for a similar number). As a condition of federal spending and tax support, universities have to accept federal regulations on university autonomy, including civil rights acts that bar discrimination of various kinds (Gladieux et al. Reference Gladieux, King, Corrigan, Altbach, Berdahl and Gumport2005: 163, 193).

Once it started, commercialization developed to consider students as customers, faculty as casual workers and higher education as an industry just like another business. One indication is that in 2019 about 63% of the faculty in the US were contingent, only 26.5% tenured and 10.5% on tenure track (Batker and Turpin Reference Batker and Turpin2023: 5). As a business, a university needs to be organized like a business; thereby a trend of corporatization emerges. Commercialization and corporatization have then become one of the larger forces influencing institutional autonomy and academic freedom (see Hao Reference Hao2020a; Shore and Taitz Reference Shore and Taitz2012: 204−205, 208−216 for the case of New Zealand; and Magalhaes et al. Reference Magalhaes, Veiga, Ribeiro and Amaral2013: 245, 249, 255, 259 for the case of Portugal, where New Public Management measures are used but institutional autonomy is not under stress). Governors and legislators have revised and restructured higher education in a number of states by pushing ‘institutions to redirect enrolments and research programs toward engineering, teacher preparation, or other state priorities’ and requiring student learning assessment and an increase in faculty teaching workload (Zusman Reference Zusman, Altbach, Berdahl and Gumport2005: 143). In the process, power is concentrated in the hands of the trustees and the president, and shared governance is being eroded.

Nonetheless, in somewhat-balanced autonomy, there is still more shared governance as compared with little or no autonomy and low autonomy. The current tension between the university and the government and between the board and the president and the faculty should not obscure the fact that the university still has much discretion to determine its course of development, although much negotiation and discussion are still needed (Zusman Reference Zusman, Altbach, Berdahl and Gumport2005: 145). After all, the boards of trustees ‘routinely approve or entirely delegate […] thousands of faculty initiatives and recommendations’ (Chait Reference Chait and Brint2002: 304). Despite all the problems discussed above, university autonomy is much more balanced, publicly accountable and socially responsive in the US in general than in many other parts of the world. So is autonomy in much of Europe, such as Norway and Portugal, and in Australia (Lackner Reference Lackner2023; Magalhaes et al. Reference Magalhaes, Veiga, Ribeiro and Amaral2013: 255, 259; Maassen et al. Reference Maassen, Gornitzka and Fumasoli2017: 247; Moses Reference Moses2007: 273). In the US, state financial support of higher education for fiscal year 2024 also saw an average increase of 10.2% (to be exact, an increase in 41 states and a decline in nine states), or a 36.5% increase over the past five years (Nietzel Reference Nietzel2024).

Conclusions and the Importance of a Federation in Balanced Autonomy

Indeed, higher education everywhere is facing challenges from governmental authoritarianism on the one hand, and internal responsibility and accountability issues on the other. But the seriousness of those challenges varies in institutions of little or no autonomy, low autonomy and somewhat-balanced autonomy. While China is an example of little or no autonomy, some national and subnational states such as Hungary, some African countries, Florida, etc., can represent the low autonomy model. Most mature democratic states are more likely to have somewhat-balanced autonomy, but it is an autonomy that still needs improvement, as discussed above, hence a call for federation and a truly balanced autonomy.

In whichever form of autonomy, the influence of the government can be both substantive and procedural. Such influences, including commercialization and corporatization, are assisted and can be resisted by the boards of trustees and presidents. But the faculty’s interaction with the two also plays an important role in deciding how much autonomy and academic freedom a university and its faculty can enjoy. A federation of all the actors is called for and needs to be established and maintained.

As Clark (Reference Clark2008: 245, 426, 472) points out, over the centuries universities have shown that they have great staying power and have adapted to every passing age, renewing and transforming themselves (i.e., in democracies mainly; see also Birnbaum and Eckel Reference Birnbaum, Eckel, Altbach, Berdahl and Gumport2005: 362 on a decentralized, flexible, moderately interdependent structure they have created). Divided power or federalism is actually a strength that allows the university to prosper, since it has a value that other organizations do not have and that society cannot do without. It is a social contract the stakeholders have made (or should make) with one another (Zusman Reference Zusman, Altbach, Berdahl and Gumport2005: 152).

Under this system of checks and balances, the faculty will have to form partnerships with the government, industry, boards of trustees, presidents and students and work out their differences and find commonalities to reach a truly balanced institutional autonomy and academic freedom (see Berdahl et al. Reference Berdahl, Altbach, Gumport, Altbach, Berdahl and Gumport2005: 7; Clark Reference Clark2008: 426; Keith Reference Keith and Tierney1998: 167; Thelin Reference Thelin2004: 344). Universities can collaborate with these partners, even with industry, without having to sacrifice their core principles of institutional autonomy and academic freedom while fulfilling their aims and purposes (Washburn Reference Washburn2005: 225).

Indeed, we need to further understand and advocate for the idea of a federation of higher education, including a reform of the governing boards to be more inclusive of faculty voices rather than representing mainly the will of the government, especially in public universities, and the making of higher education institutions into a Commonwealth University (Kaufman-Osborn Reference Kaufman-Osborn2023). It is possible for different actors in the federation to work together to produce beneficial results just as some contingent faculty members have done, as reported in Berry and Worthen (Reference Berry and Worthen2021, cited in Schrecker (Reference Schrecker and Juggernaut2024).

An effective federation of the government, trustees and presidents, and faculty and students is required for the realization of the ideal academic freedom, truly balanced institutional autonomy, and for the fulfilment of the goals of the university and the aims of a college education. In this federation, the government’s power needs to be balanced by other actors. It is a task that is much more difficult in no-autonomy and low-autonomy institutions than in somewhat-balanced autonomy institutions. But it needs to be done wherever we are.

About the Author

Zhidong Hao is Emeritus Professor of Sociology at the University of Macau. He obtained his PhD in sociology from the City University of New York in 1995 and has taught at both US and Chinese universities. He has researched the sociology of higher education, political sociology, historical sociology, sociology of religion, and sociology of intellectuals.