Introduction

India has the highest number of tuberculosis cases worldwide (World Health Organization, 2021) and 16% of the cases are among children and adolescents aged 19 years or younger (Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network, 2021). World Health Organization (WHO) defines abdominal tuberculosis as the presence of an abdominal tuberculosis specimen confirmed by clinical suspicion, laboratory, or radiological evidence (World Health Organization, 2010). Abdominal tuberculosis is difficult to diagnose because patients present with symptoms of other abdominal conditions and is associated with high resource utilization rates (Lal et al., Reference Lal, Bolia, Menon, Venkatesh, Bhatia, Vaiphei, Yadav and Sethi2020). Abdominal tuberculosis is a common condition in India; however, a search of evidence on the burden of the condition shows that there are no data on the estimates of the disease incidence. If diagnosed early, abdominal tuberculosis can be treated by medical interventions; otherwise, surgical interventions are needed (Debi et al., Reference Debi, Ravisankar, Prasad, Sinha and Sharma2014).

The Indian Government aims to provide free tuberculosis services to all people in need, but treatment for complications arising out of tuberculosis is not free, and there are no cost estimates for abdominal tuberculosis interventions (India Ministry of Health with Family Welfare, 2017). The aim of this study was to inform the planning and budgeting of abdominal tuberculosis interventions that potentially need surgery among children up to 18 years old in India by quantifying the costs associated with these patients.

Methods

Study setting, population, and data collected

This study was part of an observational clinical study conducted at Christian Medical Hospital, Ludhiana to establish the patterns of presentation and treatment outcomes for abdominal tuberculosis in an Indian setting. Abdominal tuberculosis was defined using the WHO definition in the introduction above. Data were collected from in-patient children, diagnosed with abdominal tuberculosis, who were initiated on anti-tubercular treatment and completed the treatment.

Retrospective data were collected from medical records of children treated between 1st July 2007 and 31st December 2019, and prospective data were collected from children treated between 1st January 2020 and 30th June 2021. The year 2007 was chosen as the starting point for data collection because this is the year from which abdominal tuberculosis records were available at the hospital. Where necessary, treatment completion, further resource use, and cost data for the retrospective study patients were collected from the patients’ family through phone interviews (Supplementary Material S2). Prospective study patients were followed up to 30 days from the day of treatment completion. Patients whose family could not be contacted through the phone were considered lost to follow-up.

Resource use and unit costs

Direct healthcare resource use, direct non-healthcare resource use, unit costs, and indirect costs data were collected (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Derumeaux, Rapp, Garnault, Ferlicoq, Gillette, Andrieu, Vellas, Lamure, Grand and Molinier2012). Direct healthcare resource was the direct healthcare resources used for the treatments such as surgical services, medical diagnostics, medicines, hospital stay, and post-discharge evaluations incurred at Christian Medical Hospital, Ludhiana and other healthcare providers for the same episode of abdominal tuberculosis. Direct non-healthcare resources were the resources used to access the healthcare services, which included transport, accommodation, and food, while the indirect costs were the productivity losses of missed work due to the child’s illness. The data were collected using case report forms (CRFs) presented in Table S1 and all the supplementary material are available on the Cambridge Core website (https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/experimental-results).

Unit costs were collected using the CRFs together with the resources utilized. A bottom-up estimation approach was used to value the direct resources where the quantities of the resources were multiplied by the corresponding unit costs to get the value of the resources. A top-down estimation approach was used to estimate the indirect costs by asking the respondents to estimate the overall income lost to the patient’s family because of their child’s sickness (Table S1, Question 186–188) (Ghazy et al., Reference Ghazy, Sallam, Ashmawy, Elzorkany, Reyad, Hamdy, Khedr and Mosallam2023).

Ethical considerations

The clinical study was conducted in accordance with national and institutional committees on human experimentation ethical standards and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008 (JAMA, 2013). Ethical clearance for the study was granted by the Indian Health Ministry Screening Committee (2020-4130) and Institutional Ethics Committee (IECCMCL/01-0162020). For the prospective data, the patient’s parent or guardian provided written consent indicating that they agreed to participate in the study.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted in STATA Statistical Software, version 17.0 (StataCorp LLC; College Station, TX, USA). Data were presented in terms of mean and standard deviation (SD). Cost analysis was performed from a healthcare perspective by including only the direct costs, and a secondary analysis considered the societal perspective by including the indirect costs (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Derumeaux, Rapp, Garnault, Ferlicoq, Gillette, Andrieu, Vellas, Lamure, Grand and Molinier2012). Sub-group analyses were conducted to establish the difference in costs between groups (Supplementary Material S2).

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the impact of productivity cost underreporting. The productivity costs were assumed to be 93% of all costs in line with the findings from a systematic review of tuberculosis costs in India (Sinha et al., Reference Sinha, Carwile, Bhargava, Cintron, Acuna-Villaorduna, Lakshminarayan, Liu, Kulatilaka, Locks and Hochberg2020).

Costs from 2009 to 2019 were inflated to 2020 using World Bank inflation rates taking the year of starting treatment as the year for the costs for each patient (World Bank Group, 2022). The costs were inflated to 2020 because it was the year the last patient in this study started the treatment. Costs were reported in 2020 in international dollars ($) and Indian Rupees (INR). Costs collected in INR were converted to international dollars using purchasing power parity conversion factors (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2021). All costs were discounted at 3% because it is the recommended rate in developing countries (Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, 2014).

Assumptions

The following assumptions were made when conducting the analysis:

-

• Converting the costs to a single year made the retrospective and prospective costs comparable.

-

• As this was an observational study, resource use between the retrospective and prospective patients was assumed to be similar as they received the same treatment.

Regression analysis

Regression analysis was conducted to find variables that had a significant impact on the direct cost of abdominal tuberculosis (Supplementary Material S2). A generalized linear model (GLM) with log link function and Gamma family was chosen as the appropriate model for the data (Manning & Mullahy, Reference Manning and Mullahy2001).

Missing data

Missing data were accounted for using multiple imputation, which estimated 20 imputed values of the missing variable, and then Rubin’s rules were used to combine the outputs for the imputed values (Rubin, Reference Rubin and van Buuren2018).

Results

Patients included in the study

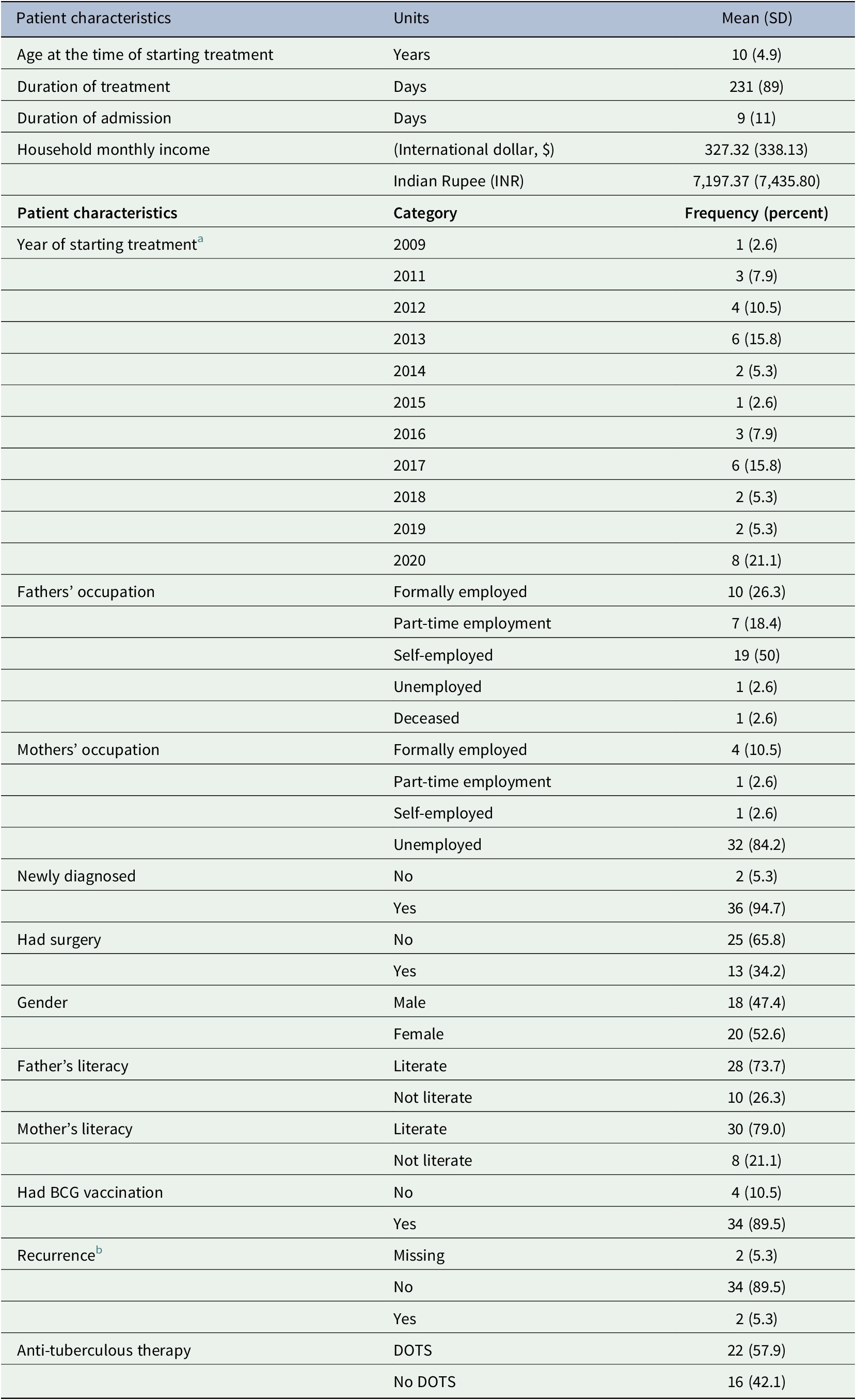

Seventy-five children were treated as in-patients for abdominal tuberculosis that potentially needed surgical intervention. Fifty-seven children completed the treatment, cost data were available from 38 of the 57 patients, and cost analysis was conducted for the 38 patients. Only 10% of the children’s fathers and 4% of the children’s mothers were in formal employment (Table 1). More characteristics of the patients in the study are presented in Supplementary Material S3.

Table 1. Patient characteristics

Abbreviations: BCG, Bacillus Calmette-Guérin; DOTS, directly observed treatment short course; SD, standard deviation.

a There were no patients that started treatment in 2010.

b The patient had recurrence of the abdominal tuberculosis.

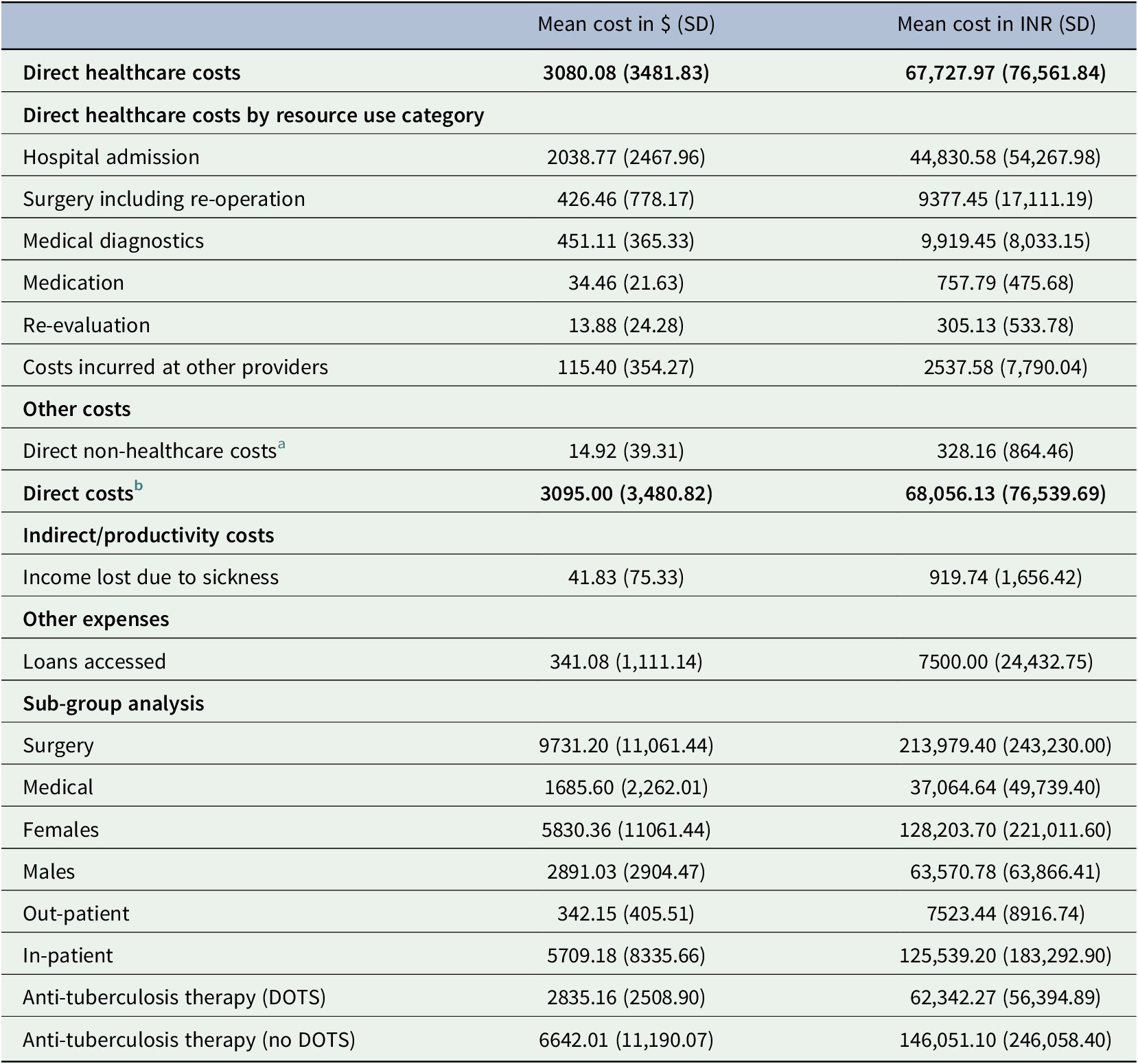

Costs

The average direct healthcare cost was $3080.80 (SD: 3481.83) or 67,727.97 INR (76,561.84) highly driven by hospital admission cost, which was $2038.77 (SD: 2467.96) or 44,830.58 INR (SD: 54,267.98) representing 66% of the direct costs (Table 2). The average cost of surgery including re-operation was $426.46 (SD: 778.17) or 9377.45 INR (SD: 17,111.19), and the average cost for medical diagnostics was $451.11 (SD: 365.33) or 9,919.45 INR (SD: 8,033.15). These costs were against an average monthly income of $327.32 (SD: 338.13) or 7197.37 INR (SD: 7,435.80) for the households of the patients in the study (Table 1). Patients had multiple diagnostic tests, especially blood tests (Supplementary Material S3).

Table 2. Cost-analysis results

Abbreviations: DOTS, directly observed treatment short course; INR, Indian Rupee; SD, standard deviation; $, international dollars.

a Includes transport, food, and accommodation.

b Combines direct healthcare and direct non-healthcare costs. Out-patient is the costs made for out-patient follow-ups. The study included patients who potentially needed surgery but after examinations some patients did not need the surgery.

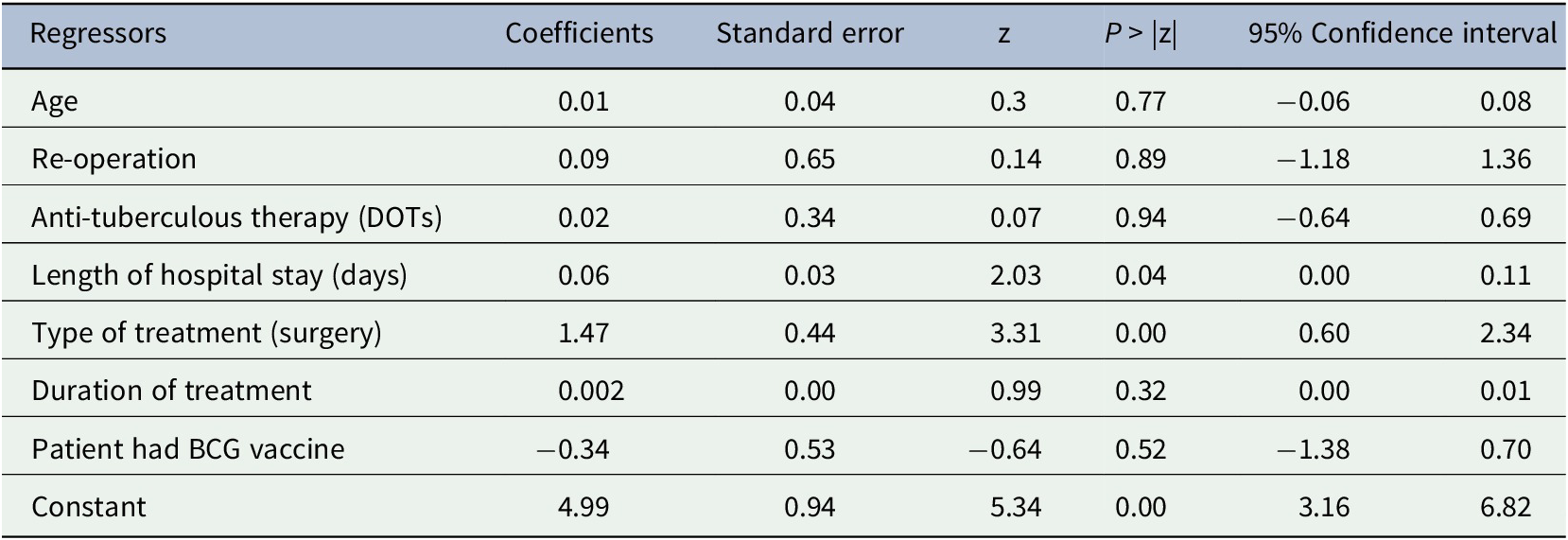

Regression results

The GLM regression results show that only length of hospital stay and surgical treatment were significantly associated with higher costs (Table 3).

Table 3. Generalized linear model regression analysis results

Abbreviations: BCG, Bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccine; DOTS, directly observed treatment short course; Z, Z-score.

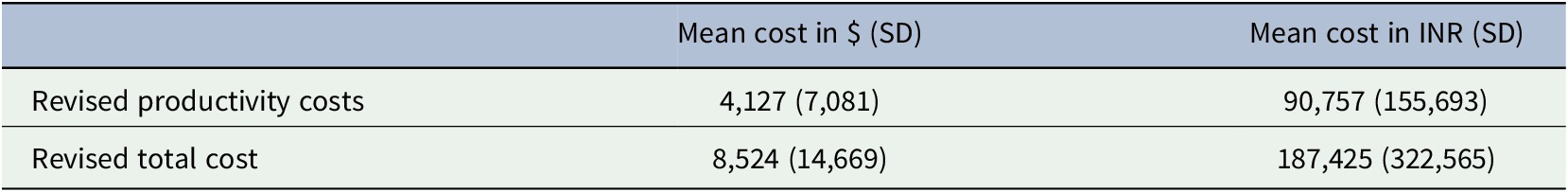

Productivity costs

The patient’s parents lost an average of 4 working days (SD: 5) due to the child’s sickness, which was associated with $41.83 (SD: 75.33) or 919.94 INR (SD: 1656.42) loss in income. The average amount of loans accessed to pay for the treatment was $341.08 (SD: 1111.14) or 7500.00 INR (SD: 24,433.75) (Table 2). However, sensitivity analysis shows that the results might have been affected by underreporting on the productivity costs as the results changed substantially when estimates on productivity costs from the literature were factored in (Table 4).

Table 4. Sensitivity analysis results

Abbreviations: INR, Indian Rupee; SD, standard deviation; $ international dollars.

Discussion

In India, the direct cost of pediatric abdominal tuberculosis that potentially needs surgical treatment was estimated to be $3095.00 (68,056.69 INR) and most of the costs were direct healthcare costs. These results were confirmed GLM regression analysis, which showed that the costs were significantly increased by an increase in duration of treatment and surgery cost that aligns with intuition. This could be because all the patients included in the study were admitted, which as expected was associated with high costs. Further, because abdominal tuberculosis is difficult to diagnose, the disease was likely diagnosed at an advanced stage, which increased the duration of treatment, resource use, and costs. These costs can potentially be avoided or reallocated if pediatric abdominal tuberculosis can be eliminated.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

This study adds to a growing body of evidence on costs of tuberculosis by focusing on pediatric abdominal tuberculosis, which has been overlooked.

This study has limitations. First, the generalizability of the results should be made with caution because the study was conducted at a single hospital and the sample size was small. Second, the retrospective data could be affected by quality of data because of relying on old records and recall bias of the respondents. Third, there was high rate of lost to follow-up (19/57). This might have resulted in bias especially by under-representing the costs of poorer patients who could not be reached for follow-up interviews because their families did not have a phone and patients treated in earlier years of the study as the contact details might have changed (Supplementary Material S4). Fourth, it was not possible to conduct patient matching by comparing the costs of abdominal tuberculosis patients to similar patients without the condition to minimize the impact of confounding variables on the results. However, regression analysis was conducted and found variables that significantly increased the costs of abdominal tuberculosis. Finally, productivity costs in this study were low compared to the direct costs maybe because all patients were children, and majority of their parents were not formally employed, as such they were likely not to report the lost productive days for doing unpaid household work. The sensitivity analysis results showed a substantial difference to the base case results because values from a single study, which only had point estimates but no SD, were used as such we could not estimate a range of values in the sensitivity analysis.

Comparisons with other studies

A systematic review of studies conducted in India found that the indirect costs for tuberculosis were higher compared to direct costs. The review reported that average direct costs range from $27 to $184 compared to $1 to $674 for indirect costs (US dollars) (Sinha et al., Reference Sinha, Carwile, Bhargava, Cintron, Acuna-Villaorduna, Lakshminarayan, Liu, Kulatilaka, Locks and Hochberg2020). The difference in costs reported in the review and the current study can be because the review included studies with costs from many hospitals including public, private, or non-governmental organization-owned hospitals, which might have different costs compared to Christian Medical Hospital, Ludhiana (Sinha et al., Reference Sinha, Carwile, Bhargava, Cintron, Acuna-Villaorduna, Lakshminarayan, Liu, Kulatilaka, Locks and Hochberg2020). The direct cost of abdominal tuberculosis in the current study was $3095.00, which is much higher than the average cost of extra-pulmonary tuberculosis, $367 US dollars, from seven health facilities in Yemen using data collected from 2008 to 2009 (Othman et al., Reference Othman, Ibrahim and Raja’a2012). The difference can be attributed to the fact that the current study included only hospitalized patients, while the earlier study did not include the cost of hospitalization. Beyond these, there was no cost evidence from high tuberculosis burden countries especially on abdominal tuberculosis.

Policy implications

The evidence in this study shows that patients do not have access to free tuberculosis services especially surgical services, and they incur huge costs. As such, free tuberculosis services should be extended to all patients in India and efforts of eliminating the condition should be strengthened.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/exp.2023.16.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/exp.2023.16.

Data availability statement

The data available have been presented in the manuscript and Supplementary material available online.

Authorship contribution

M.K. conducted the analysis, wrote, and edited the manuscript. S.S. conceptualized the cost-analysis study, conducted preliminary analysis, and wrote the manuscript. R.O. and M.M. conceptualized the cost analysis study, supervised the analysis and manuscript development, commented, and edited the manuscript. S.J., D.N.G., A.S., and J.D. conceptualized the clinical study, supervised data collection, and commented on the current manuscript. T.E.R. edited and commented on the manuscript. D.G.M. commented on the manuscript.

Funding statement

This research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) (NIHR 16.136.79) using UK aid from the UK Government to support global health research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the UK Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interest

We do not have any conflict of interests to declare.

Comments

Thank you for the opportunity to review this manuscript. Please find below a few additional comments for your consideration.

Lines 116-118: It is not very clear how top-down costing has been used here in estimating lost income. The authors refer to Table S1 which is the instrument used to collect the data. They do not direct the reader to which questions were used in calculating lost income or the detailed estimation approach.

Line 137-140: What was the conversion process? Were the costs in INR inflated to 2020 INR equivalent then converted to International dollars?

Line 159-161: Please provide an explanation here regarding the (75-38)/75 who did not have cost data. How many were lost to follow-up, how many were excluded because they were later found to have a different diagnosis etc.

Table 2: The structure is somewhat confusing. Adding subgroup totals would help guide the reader to each of the cost categories. It would also be helpful if the subcategory titles were in bold.

Line 184-186: A sensitivity analysis to inform the potential underreporting associated with self-estimated productivity losses would be useful here.

Overall, it is not coming out clearly how patients paid for the treatment. Was this captured in the CRF?