1 Introduction

In order to minimize technical difficulties, in this paper we will only discuss automorphic forms over function fields F of characteristic

![]() $\neq 2$

. Denote the adeles over F by

$\neq 2$

. Denote the adeles over F by

![]() ${\mathbb {A}}={\mathbb {A}}_F$

.

${\mathbb {A}}={\mathbb {A}}_F$

.

This paper has two parts. The first part focuses on the construction of a symmetric monoidal structure on the category of smooth representations of

![]() ${\mathrm {GL}}(2)$

over a local field. The second part uses this construction in the global setting, to construct an abelian category of ‘abstractly automorphic’ representations.

${\mathrm {GL}}(2)$

over a local field. The second part uses this construction in the global setting, to construct an abelian category of ‘abstractly automorphic’ representations.

While the first part takes up the majority of this paper, it is the author’s expectation that the second part (which uses the first in an essential way) would be the most interesting.

Therefore, before delving into the details of the first part of the paper, let us briefly discuss the second.

There is a famously unsatisfactory aspect of the global theory of automorphic representations. There is an informal analogy between the global cuspidal representations and local supercuspidal representations. Both are in some sense compactly supported: The local representations in terms of matrix coefficients, and the global representations in terms of their corresponding automorphic forms. Moreover, there is some similarity between the local theory of Jacquet modules and the global theory of constant terms. Additionally, there is similarity between the notion of parabolic induction and the notion of Eisenstein series.

This analogy between the local and global theory is fairly imprecise. Supercuspidal representations, Jacquet modules and parabolic induction all enjoy the status of functors, with clear formal properties and relationships between each other. On the other hand, cusp forms, constant terms and Eisenstein series are all considered at a lower level of categorification as maps between specific spaces of automorphic functions.

We want to strengthen this analogy by placing these constructions on an equal footing.

That is, we want to construct a category of ‘abstractly automorphic’ representations. This category should decompose as a category into a cuspidal and an Eisenstein part. Constant terms and Eisenstein series should translate into a pair of adjoint functors, and cuspidal abstractly automorphic representations should all be killed by taking their automorphic parabolic restriction. This should allow us to discuss the cuspidal automorphic spectrum in more or less the same terms as the supercuspidal local spectrum.

This paper will culminate in the construction (and proving the basic properties) of a category of abstractly automorphic representations for

![]() ${\mathrm {GL}}(2)$

over F. A detailed proof of the above properties appears in a separate paper [Reference Dor6].

${\mathrm {GL}}(2)$

over F. A detailed proof of the above properties appears in a separate paper [Reference Dor6].

The remainder of this introduction is structured as follows. In Subsection 1.1, we will describe in detail the ideas comprising Part I, as well as provide its outline. In Subsection 1.2, we will describe the ideas and outline of Part II. Finally, in Subsection 1.3, we will briefly describe Appendix A, which contains an application of the results of Part II.

1.1 Symmetric monoidal structure

Let us begin with describing in detail the ideas in the first part of this paper.

Let

![]() $(\pi ,V)$

be an automorphic representation for a reductive group G over F. Automorphic L-functions for V are usually defined via one of many different procedures. These procedures all share the following general form:

$(\pi ,V)$

be an automorphic representation for a reductive group G over F. Automorphic L-functions for V are usually defined via one of many different procedures. These procedures all share the following general form:

-

1. Take a space of test functions (e.g.,

$S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2({\mathbb {A}}))$

, the space of matrix coefficients of V, the space of vectors from V, etc.).

$S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2({\mathbb {A}}))$

, the space of matrix coefficients of V, the space of vectors from V, etc.). -

2. To each test function, assign a zeta integral – a meromorphic function in a complex variable s in some right-half-plane.

-

3. Take the greatest common divisor (GCD) of the resulting zeta integrals, guided by some place-by-place prescription to deal with the overall normalization.

The GCD we end up with is a meromorphic function in s, known as the L-function for

![]() $(\pi ,V)$

.

$(\pi ,V)$

.

The procedure above might seem rather ad hoc. Nevertheless, it gives correct results that conform to our expectations. The resulting L-functions admit analytic continuation, satisfy a functional equation and match up with those produced from Galois representations (where the procedure to produce them is much more straightforward). Much work has been done in order to systematize this kind of procedure via the use of spherical varieties (see, for example, [Reference Sakellaridis12] and [Reference Sakellaridis13]).

The research detailed in this paper was the result of taking a different point of view on these automorphic L-functions. The idea is to study the entire space of zeta integrals, instead of just the L-functions that generate them. From this point of view, it is the collection of zeta integrals itself that is important, along with the relationships between such collections. This is analogous to the way in which a vector space can be studied without necessarily specifying a concrete basis: The space of zeta integrals is analogous to the vector space, and the L-function is a basis, or a generator, for this space.

This paper is the first in a series of papers, all based on this same philosophical idea, giving a variety of results.

In this paper specifically, we will demonstrate some hidden algebraic structures that can come out of comparing different spaces of zeta integrals. We will look at automorphic representations for

![]() ${\mathrm {GL}}(2)$

, and specifically, the comparison of Godement–Jacquet and Jacquet–Langlands zeta integrals. These are two completely different constructions of the L-function for

${\mathrm {GL}}(2)$

, and specifically, the comparison of Godement–Jacquet and Jacquet–Langlands zeta integrals. These are two completely different constructions of the L-function for

![]() ${\mathrm {GL}}(2)$

, both of which give the same result. We will extend this to a canonical bijection between their spaces of zeta integrals, instead of just their L-functions. It will turn out that this point of view, where the focus is on the zeta integrals, has unexpected benefits.

${\mathrm {GL}}(2)$

, both of which give the same result. We will extend this to a canonical bijection between their spaces of zeta integrals, instead of just their L-functions. It will turn out that this point of view, where the focus is on the zeta integrals, has unexpected benefits.

To be more precise, this bijection between zeta integrals turns out to carry an algebraic structure: It induces a novel multiplicative structure on representations of

![]() ${\mathrm {GL}}(2)$

. The main focus of this paper will be refining this algebraic structure and studying some of its consequences.

${\mathrm {GL}}(2)$

. The main focus of this paper will be refining this algebraic structure and studying some of its consequences.

Let us recall each of the Godement–Jacquet and Jacquet–Langlands constructions in turn. Suppose that we are given an automorphic representation

![]() $(\pi ,V)$

. For Godement–Jacquet L-functions, one takes a smooth and compactly supported test function

$(\pi ,V)$

. For Godement–Jacquet L-functions, one takes a smooth and compactly supported test function

![]() $\Psi \in S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2({\mathbb {A}}))$

and integrates it along with a matrix coefficient

$\Psi \in S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2({\mathbb {A}}))$

and integrates it along with a matrix coefficient

![]() $\beta \in V\otimes \widetilde {V}$

to obtain the zeta integral

$\beta \in V\otimes \widetilde {V}$

to obtain the zeta integral

Here,

![]() $\widetilde {V}$

denotes the contragradient, and

$\widetilde {V}$

denotes the contragradient, and

![]() $\beta (g)$

denotes the matrix coefficient formed by contraction of

$\beta (g)$

denotes the matrix coefficient formed by contraction of

![]() $\pi (g)$

with the vector and covector defining

$\pi (g)$

with the vector and covector defining

![]() $\beta $

. The GCD of all these zeta integrals in an appropriate ring of holomorphic functions of

$\beta $

. The GCD of all these zeta integrals in an appropriate ring of holomorphic functions of

![]() $s\in {\mathbb {C}}$

is the Godement–Jacquet L-function.

$s\in {\mathbb {C}}$

is the Godement–Jacquet L-function.

However, there is an alternative approach to defining L-functions for

![]() ${\mathrm {GL}}(2)$

, by Jacquet–Langlands in the adelic formulation, based on a formulation by Hecke in more classical language (see also Remark 1.1). In this case, one takes an automorphic form

${\mathrm {GL}}(2)$

, by Jacquet–Langlands in the adelic formulation, based on a formulation by Hecke in more classical language (see also Remark 1.1). In this case, one takes an automorphic form

![]() $\phi \in V$

and integrates it along some subgroup to obtain the zeta integral

$\phi \in V$

and integrates it along some subgroup to obtain the zeta integral

$$ \begin{align} Z_{\text{JL}}\left(\phi,s\right)=\int_{{\mathbb{A}}^\times/F^\times} \phi\left(\begin{pmatrix}y & \\ & 1\end{pmatrix}\right){\left|{y}\right|}^{s-\frac{1}{2}}{\,\mathrm{d}^\times\!{y}}. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} Z_{\text{JL}}\left(\phi,s\right)=\int_{{\mathbb{A}}^\times/F^\times} \phi\left(\begin{pmatrix}y & \\ & 1\end{pmatrix}\right){\left|{y}\right|}^{s-\frac{1}{2}}{\,\mathrm{d}^\times\!{y}}. \end{align} $$

Remark 1.1. Let us make a couple of brief remarks about terminology. As stated above, the first variant of the zeta integrals we are referring to as ‘Jacquet–Langlands’ zeta integrals was introduced by Hecke in the classical language of modular forms. Later, Jacquet and Langlands gave these integrals an adelic and local interpretation. Since in this text, we are emphasizing the local case and the role of the adelic language, the author has chosen to refer to these zeta integrals as ‘Jacquet–Langlands’ zeta integrals, rather than Hecke zeta integrals (which might be further confused with the L-functions of Hecke characters).

In a similar fashion, for the sake of historical accuracy, one should also remark that what we are referring to as ‘Godement–Jacquet’ zeta integrals are generalizations to

![]() ${\mathrm {GL}}(2)$

of the ideas laid out by Tate in his thesis [Reference Tate14] and independently by Iwasawa in [Reference Iwasawa, Smith, Graves, Hille and Zariski10]. Tate’s ideas were originally stated in the adelic language, but only for

${\mathrm {GL}}(2)$

of the ideas laid out by Tate in his thesis [Reference Tate14] and independently by Iwasawa in [Reference Iwasawa, Smith, Graves, Hille and Zariski10]. Tate’s ideas were originally stated in the adelic language, but only for

![]() ${\mathrm {GL}}(1)$

, generalizing work of Riemann on the Mellin transform of theta functions.

${\mathrm {GL}}(1)$

, generalizing work of Riemann on the Mellin transform of theta functions.

Let us go back to our main line of discussion and elaborate on the structure relating the two kinds of zeta integrals. Our proof of the equivalence between Godement–Jacquet and Jacquet–Langlands L-functions will directly associate the data of a specific Godement–Jacquet zeta integral (a pair

![]() $\Psi \otimes \beta $

) with the data of a specific Jacquet–Langlands zeta integral (a form

$\Psi \otimes \beta $

) with the data of a specific Jacquet–Langlands zeta integral (a form

![]() $\phi $

). This isomorphism of ‘modules’ of zeta integrals is a categorification of the usual equivalence of L-functions.

$\phi $

). This isomorphism of ‘modules’ of zeta integrals is a categorification of the usual equivalence of L-functions.

Given the description above, one might be led to suspect the existence of some kind of algebra structure on the space

![]() of automorphic forms. After all, we are associating pairs of forms

of automorphic forms. After all, we are associating pairs of forms

![]() $\beta \in V\otimes \widetilde {V}$

with single forms

$\beta \in V\otimes \widetilde {V}$

with single forms

![]() $\phi \in V$

. Amazingly, that turns out to more or less be the case! There is, however, one caveat: The symmetric monoidal structure that one needs to use on the category of representations of

$\phi \in V$

. Amazingly, that turns out to more or less be the case! There is, however, one caveat: The symmetric monoidal structure that one needs to use on the category of representations of

![]() ${\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}})$

is not the standard one but instead a construction (related to the theta correspondence) using the space of test functions on

${\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}})$

is not the standard one but instead a construction (related to the theta correspondence) using the space of test functions on

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2({\mathbb {A}})$

.

$\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2({\mathbb {A}})$

.

The author would like to note that the papers [Reference Xue15] and in particular [Reference Fang, Sun and Xue7] study aspects of the theta correspondence that are related to this symmetric monoidal structure (although without referring to it as such).

The construction of this symmetric monoidal structure is the topic of the first part of this paper, while the algebra of automorphic functions is constructed in the second part.

A rough outline of Part I is as follows. We will begin by establishing the aforementioned correspondence between Godement–Jacquet and Jacquet–Langlands L-functions in Section 2, focusing on the local picture. This will be done by looking at the space

![]() $Y=S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)\times F^\times )$

of smooth compactly supported functions, where F is a non-Archimedean local field. This space carries a left

$Y=S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)\times F^\times )$

of smooth compactly supported functions, where F is a non-Archimedean local field. This space carries a left

![]() $G={\mathrm {GL}}_2(F)$

-action by left-multiplication on

$G={\mathrm {GL}}_2(F)$

-action by left-multiplication on

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)$

and the determinant action of G on

$\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)$

and the determinant action of G on

![]() $F^\times $

. Similarly, it also carries a right G-action by right-multiplication on

$F^\times $

. Similarly, it also carries a right G-action by right-multiplication on

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)$

and the determinant action on

$\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)$

and the determinant action on

![]() $F^\times $

. The key observation is that Y additionally carries a third, hidden, G-action that commutes with these two, coming from the Weil representation. The third action will allow us to directly relate the two kinds of zeta integrals.

$F^\times $

. The key observation is that Y additionally carries a third, hidden, G-action that commutes with these two, coming from the Weil representation. The third action will allow us to directly relate the two kinds of zeta integrals.

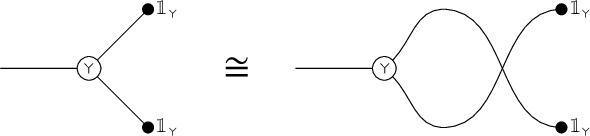

In Section 3, we will try to understand the object Y. It turns out that a useful way to do this is to change our perspective and think of the object Y as defining a tensor product operation given by

where

![]() $\otimes _G$

denotes the relative tensor product over G, that is, the universal space through which G-invariant pairings factor. The operation

$\otimes _G$

denotes the relative tensor product over G, that is, the universal space through which G-invariant pairings factor. The operation

turns out to be a unital, associative, symmetric monoidal structure on the category

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}(G)$

of smooth representations of

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}(G)$

of smooth representations of

![]() ${\mathrm {GL}}_2(F)$

. In fact, the structure of

${\mathrm {GL}}_2(F)$

. In fact, the structure of

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}(G)$

equipped with

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}(G)$

equipped with

is slightly richer:

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}(G)$

can be turned into a commutative Frobenius algebra in

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}(G)$

can be turned into a commutative Frobenius algebra in

![]() ${\mathbb {C}}$

-linear presentable categories in an appropriately categorified sense.

${\mathbb {C}}$

-linear presentable categories in an appropriately categorified sense.

1.2 Abstractly automorphic representations

Let us describe in detail the ideas in the second part of this paper.

In Part II, we will go back to the global picture. We will show that under the symmetric monoidal structure

![]() , the space

, the space

![]() of automorphic functions now carries a multiplication operation, via a kind of theta lifting. The codomain of this multiplication is not quite

of automorphic functions now carries a multiplication operation, via a kind of theta lifting. The codomain of this multiplication is not quite

![]() . However, if we denote by

. However, if we denote by

![]() ${\mathscr {I}}$

the subspace of

${\mathscr {I}}$

the subspace of

![]() which is orthogonal to all functions of the form

which is orthogonal to all functions of the form

![]() $\chi (\det (g))$

, then

$\chi (\det (g))$

, then

![]() ${\mathscr {I}}$

is closed under multiplication. This turns out to induce on

${\mathscr {I}}$

is closed under multiplication. This turns out to induce on

![]() ${\mathscr {I}}$

a structure of unital associative commutative algebra with respect to

${\mathscr {I}}$

a structure of unital associative commutative algebra with respect to

![]() . This will give us an algebra of automorphic functions.

. This will give us an algebra of automorphic functions.

We will use this construction, the algebra structure on

![]() ${\mathscr {I}}$

, to construct a category of what we refer to as abstractly automorphic representations. Specifically, given a monoidal category

${\mathscr {I}}$

, to construct a category of what we refer to as abstractly automorphic representations. Specifically, given a monoidal category

![]() $({\mathcal {C}},\otimes )$

and an algebra object

$({\mathcal {C}},\otimes )$

and an algebra object

![]() $A\in {\mathcal {C}}$

with respect to its monoidal structure

$A\in {\mathcal {C}}$

with respect to its monoidal structure

![]() $\otimes $

, one can construct the category of A-modules in

$\otimes $

, one can construct the category of A-modules in

![]() ${\mathcal {C}}$

. This is given by the category of objects

${\mathcal {C}}$

. This is given by the category of objects

![]() $M\in {\mathcal {C}}$

, along with action maps

$M\in {\mathcal {C}}$

, along with action maps

satisfying the usual axioms.

By applying this construction to the algebra object

![]() ${\mathscr {I}}$

with respect to the monoidal structure

${\mathscr {I}}$

with respect to the monoidal structure

![]() , we obtain the category of

, we obtain the category of

![]() ${\mathscr {I}}$

-modules in

${\mathscr {I}}$

-modules in

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}({\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}}))$

, which we denote by

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}({\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}}))$

, which we denote by

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}^{\mathrm {aut}}({\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}}))$

, and refer to as the category of abstractly automorphic representations.

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}^{\mathrm {aut}}({\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}}))$

, and refer to as the category of abstractly automorphic representations.

The category

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}^{\mathrm {aut}}({\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}}))$

is canonically equipped with a forgetful functor

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}^{\mathrm {aut}}({\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}}))$

is canonically equipped with a forgetful functor

which turns out to be fully faithful in our case. This means that being an abstractly automorphic representation (or, more concretely, an

![]() ${\mathscr {I}}$

-module) is a mere property of a

${\mathscr {I}}$

-module) is a mere property of a

![]() ${\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}})$

-module. We choose to interpret this property as an automorphicity property for

${\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}})$

-module. We choose to interpret this property as an automorphicity property for

![]() ${\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}})$

-modules, which we call abstract automorphicity.

${\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}})$

-modules, which we call abstract automorphicity.

The question of what, exactly, is an automorphic representation is an old one. It is generally accepted that an irreducible representation is automorphic if it is a subquotient of an appropriate space

![]() of functions on

of functions on

![]() ${\mathrm {GL}}_2(F)\backslash {\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}})$

(this is, for example, the definition used in [Reference Langlands11]). However, these irreducible automorphic representations do not seem to be known to fit into any natural category.

${\mathrm {GL}}_2(F)\backslash {\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}})$

(this is, for example, the definition used in [Reference Langlands11]). However, these irreducible automorphic representations do not seem to be known to fit into any natural category.

We propose that the category

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}^{\mathrm {aut}}({\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}}))$

of abstractly automorphic representations can be taken as an answer to this question. A key property of the abelian category

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}^{\mathrm {aut}}({\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}}))$

of abstractly automorphic representations can be taken as an answer to this question. A key property of the abelian category

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}^{\mathrm {aut}}({\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}}))$

, which helps justify its name, is that its irreducible objects are precisely the irreducible automorphic representations in the above sense (although the proof of this result lies outside the scope of this paper; see [Reference Dor6] for the proof). In particular, this seems to allow the use of more categorical methods in the theory of automorphic representations.

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}^{\mathrm {aut}}({\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}}))$

, which helps justify its name, is that its irreducible objects are precisely the irreducible automorphic representations in the above sense (although the proof of this result lies outside the scope of this paper; see [Reference Dor6] for the proof). In particular, this seems to allow the use of more categorical methods in the theory of automorphic representations.

The detailed study of the category

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}^{\mathrm {aut}}({\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}}))$

lies outside the scope of this paper. Nevertheless, it appears to be much better behaved than the ambient category

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}^{\mathrm {aut}}({\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}}))$

lies outside the scope of this paper. Nevertheless, it appears to be much better behaved than the ambient category

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}({\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}}))$

of smooth

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}({\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}}))$

of smooth

![]() ${\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}})$

-modules. For example, although we will only show this in a follow-on paper [Reference Dor6], the category

${\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}})$

-modules. For example, although we will only show this in a follow-on paper [Reference Dor6], the category

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}^{\mathrm {aut}}({\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}}))$

admits a decomposition into components that are either induced from

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}^{\mathrm {aut}}({\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}}))$

admits a decomposition into components that are either induced from

![]() ${\mathrm {GL}}(1)\times {\mathrm {GL}}(1)$

(corresponding to Eisenstein series) or cuspidal in nature (corresponding to cuspidal automorphic representations), in analogy to the local theory of representations of

${\mathrm {GL}}(1)\times {\mathrm {GL}}(1)$

(corresponding to Eisenstein series) or cuspidal in nature (corresponding to cuspidal automorphic representations), in analogy to the local theory of representations of

![]() ${\mathrm {GL}}(2)$

.

${\mathrm {GL}}(2)$

.

The category

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}^{\mathrm {aut}}({\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}}))$

will be described in Subsection 4.6.

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}^{\mathrm {aut}}({\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}}))$

will be described in Subsection 4.6.

Example 1.2. One way to think of the multiplicative structure on

![]() ${\mathscr {I}}$

is to compare it to the commutative case.

${\mathscr {I}}$

is to compare it to the commutative case.

Let H be a commutative group, and let

![]() $\Gamma \subseteq H$

be a subgroup. Then the space of functions on

$\Gamma \subseteq H$

be a subgroup. Then the space of functions on

![]() $\Gamma \backslash H$

admits an algebra structure, given by the convolution product with respect to H.

$\Gamma \backslash H$

admits an algebra structure, given by the convolution product with respect to H.

If we think of H as being analogous to

![]() ${\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}})$

and

${\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}})$

and

![]() $\Gamma $

as being analogous to

$\Gamma $

as being analogous to

![]() ${\mathrm {GL}}_2(F)$

, then we can justify thinking of the algebra structure of

${\mathrm {GL}}_2(F)$

, then we can justify thinking of the algebra structure of

![]() ${\mathscr {I}}$

as being a kind of convolution product. In a sense, the nonstandard symmetric monoidal structure

${\mathscr {I}}$

as being a kind of convolution product. In a sense, the nonstandard symmetric monoidal structure

![]() allows inherently commutative phenomena to manifest for the noncommutative group

allows inherently commutative phenomena to manifest for the noncommutative group

![]() ${\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}})$

. See also Remarks 3.1 and 4.1.

${\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}})$

. See also Remarks 3.1 and 4.1.

Remark 1.3. Let us make a much more speculative remark.

The author believes that it would be interesting to generalize the results of this paper to groups other than

![]() ${\mathrm {GL}}(2)$

. At the very least, if B is a quaternion algebra over F, then it is possible to place the theta correspondence between

${\mathrm {GL}}(2)$

. At the very least, if B is a quaternion algebra over F, then it is possible to place the theta correspondence between

![]() $B^\times $

and

$B^\times $

and

![]() ${\mathrm {GL}}(2)$

into the same framework of symmetric monoidal and module structures as this paper. The author intends to do so in a subsequent paper.

${\mathrm {GL}}(2)$

into the same framework of symmetric monoidal and module structures as this paper. The author intends to do so in a subsequent paper.

Regardless, the author has not yet been able to take this theory beyond

![]() ${\mathrm {GL}}(2)$

and its inner forms. However, it is possible to formulate some expectations for such a generalization. Essentially, for a reductive group G, one can hope to construct some category

${\mathrm {GL}}(2)$

and its inner forms. However, it is possible to formulate some expectations for such a generalization. Essentially, for a reductive group G, one can hope to construct some category

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}^{\mathrm {aut}}(G({\mathbb {A}}))$

of abstractly automorphic

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}^{\mathrm {aut}}(G({\mathbb {A}}))$

of abstractly automorphic

![]() $G({\mathbb {A}})$

-modules. We can expect that there will be a realization functor

$G({\mathbb {A}})$

-modules. We can expect that there will be a realization functor

but it seems too harsh to demand that the realization functor be fully faithful outside the case of

![]() $G={\mathrm {GL}}(n)$

.

$G={\mathrm {GL}}(n)$

.

1.3 Additional consequences

Before ending this introduction, let us mention one more interesting consequence of our construction of the algebra

![]() ${\mathscr {I}}$

of automorphic functions. Consider the space

${\mathscr {I}}$

of automorphic functions. Consider the space

![]() ${\mathscr {I}}_{/\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2({\mathcal {O}}_{\mathbb {A}})}$

of coinvariants of

${\mathscr {I}}_{/\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2({\mathcal {O}}_{\mathbb {A}})}$

of coinvariants of

![]() ${\mathscr {I}}$

with respect to the action of

${\mathscr {I}}$

with respect to the action of

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2({\mathcal {O}}_{\mathbb {A}})$

, where

$\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2({\mathcal {O}}_{\mathbb {A}})$

, where

![]() ${\mathcal {O}}_{\mathbb {A}}\subseteq {\mathbb {A}}$

is the subring of all adeles which are integral at all places. Note that

${\mathcal {O}}_{\mathbb {A}}\subseteq {\mathbb {A}}$

is the subring of all adeles which are integral at all places. Note that

![]() ${\mathscr {I}}_{/\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2({\mathcal {O}}_{\mathbb {A}})}$

is the space of all smooth compactly supported spherical automorphic functions that are orthogonal to all one-dimensional characters (note that because

${\mathscr {I}}_{/\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2({\mathcal {O}}_{\mathbb {A}})}$

is the space of all smooth compactly supported spherical automorphic functions that are orthogonal to all one-dimensional characters (note that because

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2({\mathcal {O}}_{\mathbb {A}})$

is compact, it does not matter whether we take invariants or coinvariants).

$\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2({\mathcal {O}}_{\mathbb {A}})$

is compact, it does not matter whether we take invariants or coinvariants).

The algebra structure of the space

![]() ${\mathscr {I}}$

with respect to

${\mathscr {I}}$

with respect to

![]() will, as a special case, automatically equip the space

will, as a special case, automatically equip the space

![]() ${\mathscr {I}}_{/\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2({\mathcal {O}}_{\mathbb {A}})}$

with the structure of a commutative algebra with respect to the usual tensor product

${\mathscr {I}}_{/\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2({\mathcal {O}}_{\mathbb {A}})}$

with the structure of a commutative algebra with respect to the usual tensor product

![]() $\otimes $

(up to choice of a piece of global data called an unramified spin structure; see Appendix A). This algebra structure is different from the usual pointwise multiplication and respects the action of the center of the category

$\otimes $

(up to choice of a piece of global data called an unramified spin structure; see Appendix A). This algebra structure is different from the usual pointwise multiplication and respects the action of the center of the category

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}({\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}}))$

. This can be thought of as a kind of convolution product for spherical automorphic functions in the following sense.

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}({\mathrm {GL}}_2({\mathbb {A}}))$

. This can be thought of as a kind of convolution product for spherical automorphic functions in the following sense.

The space

![]() ${\mathscr {I}}_{/\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2({\mathcal {O}}_{\mathbb {A}})}$

of spherical automorphic functions has a Fourier transform. Specifically, the Hecke operators act on this space, and therefore it defines a module on the spectrum of all Hecke operators. Classically, one can try to identify this module with the structure sheaf of its support on the spectrum of the Hecke operators and thus associate to each function

${\mathscr {I}}_{/\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2({\mathcal {O}}_{\mathbb {A}})}$

of spherical automorphic functions has a Fourier transform. Specifically, the Hecke operators act on this space, and therefore it defines a module on the spectrum of all Hecke operators. Classically, one can try to identify this module with the structure sheaf of its support on the spectrum of the Hecke operators and thus associate to each function

![]() $\phi \in {\mathscr {I}}_{/\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2({\mathcal {O}}_{\mathbb {A}})}$

a function on the unramified automorphic spectrum. However, this association is noncanonical. This manifests as our freedom to choose different unramified vectors at each unramified automorphic representation. In particular, it makes no sense to talk about the convolution of two functions

$\phi \in {\mathscr {I}}_{/\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2({\mathcal {O}}_{\mathbb {A}})}$

a function on the unramified automorphic spectrum. However, this association is noncanonical. This manifests as our freedom to choose different unramified vectors at each unramified automorphic representation. In particular, it makes no sense to talk about the convolution of two functions

![]() $\phi ,\phi '\in {\mathscr {I}}_{/\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2({\mathcal {O}}_{\mathbb {A}})}$

.

$\phi ,\phi '\in {\mathscr {I}}_{/\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2({\mathcal {O}}_{\mathbb {A}})}$

.

However, the commutative algebra structure on

![]() ${\mathscr {I}}_{/\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2({\mathcal {O}}_{\mathbb {A}})}$

allows us to make this canonical. Given an unramified spin structure, we can canonically identify functions

${\mathscr {I}}_{/\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2({\mathcal {O}}_{\mathbb {A}})}$

allows us to make this canonical. Given an unramified spin structure, we can canonically identify functions

![]() $\phi \in {\mathscr {I}}_{/\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2({\mathcal {O}}_{\mathbb {A}})}$

with functions on the unramified automorphic spectrum (by a certain normalization of their Whittaker coefficients). In the most abstract terms, one can think of the algebraic spectrum

$\phi \in {\mathscr {I}}_{/\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2({\mathcal {O}}_{\mathbb {A}})}$

with functions on the unramified automorphic spectrum (by a certain normalization of their Whittaker coefficients). In the most abstract terms, one can think of the algebraic spectrum

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Spec}}{{\mathscr {I}}_{/\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2({\mathcal {O}}_{\mathbb {A}})}}$

as a space and of elements of

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Spec}}{{\mathscr {I}}_{/\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2({\mathcal {O}}_{\mathbb {A}})}}$

as a space and of elements of

![]() ${\mathscr {I}}_{/\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2({\mathcal {O}}_{\mathbb {A}})}$

as functions on it. With this identification, the multiplication of

${\mathscr {I}}_{/\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2({\mathcal {O}}_{\mathbb {A}})}$

as functions on it. With this identification, the multiplication of

![]() ${\mathscr {I}}_{/\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2({\mathcal {O}}_{\mathbb {A}})}$

corresponds to pointwise multiplication on the spectrum and is thus a convolution product.

${\mathscr {I}}_{/\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2({\mathcal {O}}_{\mathbb {A}})}$

corresponds to pointwise multiplication on the spectrum and is thus a convolution product.

This multiplicative structure will be described in Appendix A.

Remark 1.4. One can speculate about the relationship of our construction with the geometric Langlands conjectures. Let C be a smooth proper curve over

![]() ${\mathbb {C}}$

. Then the geometric Langlands conjectures predict the equivalence of a certain category of D-modules on

${\mathbb {C}}$

. Then the geometric Langlands conjectures predict the equivalence of a certain category of D-modules on

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Bun}}_{{\mathrm {GL}}_2}(C)$

with a certain category of sheaves of modules over

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Bun}}_{{\mathrm {GL}}_2}(C)$

with a certain category of sheaves of modules over

![]() $\mathrm {LocSys}_{{\mathrm {GL}}_2^\vee }(C)$

. Now, the category of D-modules over

$\mathrm {LocSys}_{{\mathrm {GL}}_2^\vee }(C)$

. Now, the category of D-modules over

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Bun}}_{{\mathrm {GL}}_2}(C)$

carries a symmetric monoidal structure, corresponding after decategorification to the pointwise multiplication of unramified automorphic functions.

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Bun}}_{{\mathrm {GL}}_2}(C)$

carries a symmetric monoidal structure, corresponding after decategorification to the pointwise multiplication of unramified automorphic functions.

However, one can speculate about giving this category a symmetric monoidal structure inherited from the other side of this equivalence, for example, from the

![]() $!$

-tensor product of

$!$

-tensor product of

![]() $\mathrm {LocSys}_{{\mathrm {GL}}_2^\vee }(C)$

. This should correspond to a ‘spectral’ product, or a convolution product, on unramified automorphic forms after decategorification. The author believes that it would be interesting to attempt to relate this structure to the convolution product on

$\mathrm {LocSys}_{{\mathrm {GL}}_2^\vee }(C)$

. This should correspond to a ‘spectral’ product, or a convolution product, on unramified automorphic forms after decategorification. The author believes that it would be interesting to attempt to relate this structure to the convolution product on

![]() ${\mathscr {I}}_{/\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2({\mathcal {O}}_{\mathbb {A}})}$

described above.

${\mathscr {I}}_{/\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2({\mathcal {O}}_{\mathbb {A}})}$

described above.

Part I

Symmetric monoidal structure

2 Godement–Jacquet versus Jacquet–Langlands

2.1 Introduction

Let F be a non-Archimedean local field with

![]() ${\text {char}}(F)\neq 2$

. In this section, we will attempt to give a new point of view on the equivalence between the Godement–Jacquet L-functions of representations of

${\text {char}}(F)\neq 2$

. In this section, we will attempt to give a new point of view on the equivalence between the Godement–Jacquet L-functions of representations of

![]() $G={\mathrm {GL}}_2(F)$

and the Jacquet–Langlands L-functions of the same representations.

$G={\mathrm {GL}}_2(F)$

and the Jacquet–Langlands L-functions of the same representations.

Consider the G-bi-module

![]() $S({\mathrm {GL}}_2(F))$

of smooth and compactly supported functions on

$S({\mathrm {GL}}_2(F))$

of smooth and compactly supported functions on

![]() ${\mathrm {GL}}_2(F)$

, and fix the standard Haar measure

${\mathrm {GL}}_2(F)$

, and fix the standard Haar measure

![]() ${\,\mathrm {d}^\times \!{g}} $

on

${\,\mathrm {d}^\times \!{g}} $

on

![]() ${\mathrm {GL}}_2(F)$

such that the volume of a maximal compact subgroup is

${\mathrm {GL}}_2(F)$

such that the volume of a maximal compact subgroup is

![]() $1$

. The spectral decomposition of this bimodule is well known; for a pair of irreducible representations

$1$

. The spectral decomposition of this bimodule is well known; for a pair of irreducible representations

![]() $(\pi ,V)$

and

$(\pi ,V)$

and

![]() $(\pi ',V')$

, we have

$(\pi ',V')$

, we have

if

![]() $V\cong V'$

, and

$V\cong V'$

, and

otherwise, where

![]() $\tilde {V}$

is the contragradient of V, considered as a right G-module.

$\tilde {V}$

is the contragradient of V, considered as a right G-module.

In other words, every G-bi-module

![]() $V\otimes _{\mathbb {C}}\tilde {V}$

appears ‘once’ in the spectral decomposition of

$V\otimes _{\mathbb {C}}\tilde {V}$

appears ‘once’ in the spectral decomposition of

![]() $S({\mathrm {GL}}_2(F))$

. To truly specify this decomposition, one needs to also discuss the dependence of this decomposition on the continuous part of the spectrum, but let us ignore this for now.

$S({\mathrm {GL}}_2(F))$

. To truly specify this decomposition, one needs to also discuss the dependence of this decomposition on the continuous part of the spectrum, but let us ignore this for now.

A question we can ask, then, is what is the spectral decomposition of the space

![]() $S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))$

. The answer to this question should be fairly deep as it relates to the Godement–Jacquet construction of L-functions. The simplest aspect of this we can ask about is to compute the spaces

$S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))$

. The answer to this question should be fairly deep as it relates to the Godement–Jacquet construction of L-functions. The simplest aspect of this we can ask about is to compute the spaces

with

![]() $(\pi ,V)$

irreducible. Here, the Schwartz space

$(\pi ,V)$

irreducible. Here, the Schwartz space

![]() $S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))$

is the space of smooth and compactly supported functions on

$S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))$

is the space of smooth and compactly supported functions on

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)$

. We restrict to the case where

$\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)$

. We restrict to the case where

![]() $(\pi ,V)$

is generic, that is, has a Kirillov model. Note that we are also only looking at the diagonal part of the spectral decomposition, which we justify by observing that the two actions of the Bernstein center of G on

$(\pi ,V)$

is generic, that is, has a Kirillov model. Note that we are also only looking at the diagonal part of the spectral decomposition, which we justify by observing that the two actions of the Bernstein center of G on

![]() $S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))$

coincide (this follows because the two actions of the center on

$S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))$

coincide (this follows because the two actions of the center on

![]() $S(G)$

coincide, as well as the fact that

$S(G)$

coincide, as well as the fact that

![]() $S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))$

embeds in the contragradient of

$S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))$

embeds in the contragradient of

![]() $S(G)$

). This means that off-diagonal components

$S(G)$

). This means that off-diagonal components

with

![]() $V'\neq V$

generic are

$V'\neq V$

generic are

![]() $0$

.

$0$

.

The space

![]() $\tilde {V}\otimes _G S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))\otimes _G V$

turns out to be a one-dimensional vector space. However, this answer in not too meaningful. We would like to say which one-dimensional vector space this is. In order to be able to make interesting statements about it, we should give it some more structure. So, consider instead the space

$\tilde {V}\otimes _G S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))\otimes _G V$

turns out to be a one-dimensional vector space. However, this answer in not too meaningful. We would like to say which one-dimensional vector space this is. In order to be able to make interesting statements about it, we should give it some more structure. So, consider instead the space

![]() $Y=S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)\times F^\times )$

. We let G act on

$Y=S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)\times F^\times )$

. We let G act on

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)\times F^\times $

from both sides as

$\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)\times F^\times $

from both sides as

which turns

![]() $Y=S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)\times F^\times )$

into a G-bi-module. Therefore, we want to compute the space

$Y=S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)\times F^\times )$

into a G-bi-module. Therefore, we want to compute the space

which now has an extra structure of

![]() $F^\times $

-module, via the action of

$F^\times $

-module, via the action of

![]() $F^\times $

on the second term in the product

$F^\times $

on the second term in the product

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)\times F^\times $

. The desired space

$\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)\times F^\times $

. The desired space

![]() $\tilde {V}\otimes _G S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))\otimes _G V$

is canonically the space of coinvariants of

$\tilde {V}\otimes _G S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))\otimes _G V$

is canonically the space of coinvariants of

![]() $\tilde {V}\otimes _G Y\otimes _G V$

under this

$\tilde {V}\otimes _G Y\otimes _G V$

under this

![]() $F^\times $

-action.

$F^\times $

-action.

Spectrally, the operation sending the G-bi-module

![]() $S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))$

to the

$S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))$

to the

![]() $F^\times $

-module

$F^\times $

-module

![]() $\tilde {V}\otimes _G S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)\times F^\times )\otimes _G V$

can be described as follows. Given a character

$\tilde {V}\otimes _G S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)\times F^\times )\otimes _G V$

can be described as follows. Given a character

![]() $\chi {\,:\,} F^\times \rightarrow {\mathbb {C}}^\times $

, the component of

$\chi {\,:\,} F^\times \rightarrow {\mathbb {C}}^\times $

, the component of

![]() $\tilde {V}\otimes _G S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)\times F^\times )\otimes _G V$

at

$\tilde {V}\otimes _G S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)\times F^\times )\otimes _G V$

at

![]() $\chi $

is the same as the component of

$\chi $

is the same as the component of

![]() $S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))$

at the exterior product of

$S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))$

at the exterior product of

![]() $\pi \times (\chi \circ \det )$

with itself.

$\pi \times (\chi \circ \det )$

with itself.

In order to have an idea of the answer, we can start by considering the

![]() $G\times G$

-submodule

$G\times G$

-submodule

![]() $Y^\circ =S({\mathrm {GL}}_2(F)\times F^\times )$

of Y. It is easy to see that there is a canonical isomorphism

$Y^\circ =S({\mathrm {GL}}_2(F)\times F^\times )$

of Y. It is easy to see that there is a canonical isomorphism

given by the formula

Since

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)$

is some completion of

$\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)$

is some completion of

![]() ${\mathrm {GL}}_2(F)$

, we can expect

${\mathrm {GL}}_2(F)$

, we can expect

![]() $\tilde {V}\otimes _G Y\otimes _G V$

to be some extension of

$\tilde {V}\otimes _G Y\otimes _G V$

to be some extension of

![]() $S(F^\times )$

.

$S(F^\times )$

.

2.1.1 Statement of the main result

We want to decompose the

![]() $G\times G$

-module Y. It turns out that we can do this by introducing a third action of G on this space, coming from the Weil representation.

$G\times G$

-module Y. It turns out that we can do this by introducing a third action of G on this space, coming from the Weil representation.

Fix a nontrivial additive character

![]() $e{\,:\,} F \rightarrow {\mathbb {C}}^\times $

, and let

$e{\,:\,} F \rightarrow {\mathbb {C}}^\times $

, and let

![]() $\theta $

be the corresponding character on the subgroup

$\theta $

be the corresponding character on the subgroup

![]() $U=U_2(F)\subseteq {\mathrm {GL}}_2(F)$

of upper triangular unipotent matrices, defined by

$U=U_2(F)\subseteq {\mathrm {GL}}_2(F)$

of upper triangular unipotent matrices, defined by

$$ \begin{align*} \theta{\,:\,} U & \rightarrow {\mathbb{C}}^\times \\ \theta\left(\begin{pmatrix}1 & u \\ & 1\end{pmatrix}\right) & =e(u). \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \theta{\,:\,} U & \rightarrow {\mathbb{C}}^\times \\ \theta\left(\begin{pmatrix}1 & u \\ & 1\end{pmatrix}\right) & =e(u). \end{align*} $$

For any generic irreducible G-module V, we denote by

![]() $V(n)$

the twist of V by

$V(n)$

the twist of V by

![]() ${\left |{\det (\cdot )}\right |}^{n}$

.

${\left |{\det (\cdot )}\right |}^{n}$

.

Recollection 2.1. Recall that for a generic irreducible G-module V, the Kirillov model

![]() $\mathcal {K}(V)$

of V is defined as follows.

$\mathcal {K}(V)$

of V is defined as follows.

Let

$P=\left \{\begin {pmatrix}* & * \\ & 1\end {pmatrix}\right \}\subseteq G$

be the mirabolic subgroup. Let

$P=\left \{\begin {pmatrix}* & * \\ & 1\end {pmatrix}\right \}\subseteq G$

be the mirabolic subgroup. Let

![]() $\Phi ^-{\,:\,}\operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}(P) \rightarrow {\mathrm {Vect}}$

be the functor that takes a P-module to its

$\Phi ^-{\,:\,}\operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}(P) \rightarrow {\mathrm {Vect}}$

be the functor that takes a P-module to its

![]() $\theta $

-equivariant quotient, for the nontrivial character

$\theta $

-equivariant quotient, for the nontrivial character

![]() $\theta $

on the unipotent radical of P (see [Reference Bernstein and Zelevinsky3] for this notation). Let

$\theta $

on the unipotent radical of P (see [Reference Bernstein and Zelevinsky3] for this notation). Let

![]() $\Phi ^+{\,:\,}{\mathrm {Vect}} \rightarrow \operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}(P)$

be its left adjoint, given by

$\Phi ^+{\,:\,}{\mathrm {Vect}} \rightarrow \operatorname {\mathrm {Mod}}(P)$

be its left adjoint, given by

![]() $\theta $

-equivariant induction with compact support (see Proposition 3.2 of [Reference Bernstein and Zelevinsky3]).

$\theta $

-equivariant induction with compact support (see Proposition 3.2 of [Reference Bernstein and Zelevinsky3]).

It is well known that the space

![]() $\Phi ^-\tilde {V}$

is one dimensional. A choice of vector

$\Phi ^-\tilde {V}$

is one dimensional. A choice of vector

![]() ${\mathbb {C}} \rightarrow \Phi ^-\tilde {V}$

gives, by adjunction, a map of P-modules

${\mathbb {C}} \rightarrow \Phi ^-\tilde {V}$

gives, by adjunction, a map of P-modules

Taking the dual map, we obtain a morphism of P-modules

where

![]() $\widetilde {S(F^\times )}$

is identified with the space of uniformly smooth functions on

$\widetilde {S(F^\times )}$

is identified with the space of uniformly smooth functions on

![]() $F^\times $

, and P acts on

$F^\times $

, and P acts on

![]() $\widetilde {S(F^\times )}$

by

$\widetilde {S(F^\times )}$

by

$$\begin{align*}\begin{pmatrix}a & b \\ & 1\end{pmatrix}\cdot f(y)=e(by)f(ay). \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\begin{pmatrix}a & b \\ & 1\end{pmatrix}\cdot f(y)=e(by)f(ay). \end{align*}$$

The map

![]() $V \rightarrow \widetilde {S(F^\times )}$

is the unique nonzero map of P-modules from V to

$V \rightarrow \widetilde {S(F^\times )}$

is the unique nonzero map of P-modules from V to

![]() $\widetilde {S(F^\times )}$

, up to scalar. Such maps are injective and have the same image. This image is called the Kirillov model

$\widetilde {S(F^\times )}$

, up to scalar. Such maps are injective and have the same image. This image is called the Kirillov model

![]() $\mathcal {K}(V)$

of V, and it acquires a canonical G-action from V [Reference Goldfeld and Hundley8, Theorem 6.7.2].

$\mathcal {K}(V)$

of V, and it acquires a canonical G-action from V [Reference Goldfeld and Hundley8, Theorem 6.7.2].

There is a related notion, called the Whittaker model of V. This model is obtained by taking the map

![]() $S(F^\times ) \rightarrow \tilde {V}$

of P-modules above and extending it to a map of G-modules:

$S(F^\times ) \rightarrow \tilde {V}$

of P-modules above and extending it to a map of G-modules:

by letting

be the induction with compact support of

![]() $S(F^\times )$

from P to G (see also Construction 3.10 where we give an isomorphic construction of the same space, given a choice of measure on

$S(F^\times )$

from P to G (see also Construction 3.10 where we give an isomorphic construction of the same space, given a choice of measure on

![]() $F^\times $

). The space

$F^\times $

). The space

is called the Whittaker space, and the image of the resulting dual map

is called the Whittaker model of V. Our notation for the Whittaker space is nonstandard.

Theorem 2.2. There exists an additional canonical G-action

![]() $\tau $

on Y. This action is uniquely determined by the following properties:

$\tau $

on Y. This action is uniquely determined by the following properties:

-

1. The action

$\tau $

commutes with the existing G-actions on Y from the left and the right.

$\tau $

commutes with the existing G-actions on Y from the left and the right. -

2. For every generic irreducible

$(\pi ,V)$

, there is an isomorphism of G-modules

$(\pi ,V)$

, there is an isomorphism of G-modules  $$\begin{align*}\nu{\,:\,}\tilde{V}\otimes_G Y\otimes_G V\xrightarrow{\sim}\mathcal{K}(V(-1))(1). \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\nu{\,:\,}\tilde{V}\otimes_G Y\otimes_G V\xrightarrow{\sim}\mathcal{K}(V(-1))(1). \end{align*}$$

-

3. The isomorphism

$\nu $

above fits into the commutative diagram (2.3)where

$\nu $

above fits into the commutative diagram (2.3)where

$\mu $

is as in equation (2.2), the left vertical map is induced from the natural inclusion

$\mu $

is as in equation (2.2), the left vertical map is induced from the natural inclusion

$Y^\circ \subseteq Y$

and the right vertical map is the inclusion of

$Y^\circ \subseteq Y$

and the right vertical map is the inclusion of

$S(F^\times )$

into the Kirillov model

$S(F^\times )$

into the Kirillov model

$\mathcal {K}(V(-1))$

of

$\mathcal {K}(V(-1))$

of

$V(-1)$

.

$V(-1)$

.

Remark 2.3. Note that in Item 2 above, the right-hand side

![]() $\mathcal {K}(V(-1))(1)$

is isomorphic to V as a representation of G, but ‘rigidified’ via the use of Kirillov models (in the sense that while an irreducible representation is only unique up to automorphism, the Kirillov model is a canonical realization of that representation).

$\mathcal {K}(V(-1))(1)$

is isomorphic to V as a representation of G, but ‘rigidified’ via the use of Kirillov models (in the sense that while an irreducible representation is only unique up to automorphism, the Kirillov model is a canonical realization of that representation).

Remark 2.4. Note that the right vertical map appearing in diagram (2.3) is not P-equivariant. Rather, this map is twisted-P-equivariant, with respect to the character

![]() ${\left |{\det (\cdot )}\right |}$

. The reason for this twist ultimately stems from an off-by-one in the variable s between Jacquet–Langlands and Godement–Jacquet zeta integrals: The formula for the Jacquet–Langlands zeta integral takes

${\left |{\det (\cdot )}\right |}$

. The reason for this twist ultimately stems from an off-by-one in the variable s between Jacquet–Langlands and Godement–Jacquet zeta integrals: The formula for the Jacquet–Langlands zeta integral takes

![]() ${\left |{y}\right |}$

to the power of

${\left |{y}\right |}$

to the power of

![]() $s-\frac {1}{2}$

, while the formula for the Godement–Jacquet zeta integral takes

$s-\frac {1}{2}$

, while the formula for the Godement–Jacquet zeta integral takes

![]() ${\left |{\det (g)}\right |}$

to the power of

${\left |{\det (g)}\right |}$

to the power of

![]() $s+\frac {1}{2}$

(see, for example, the form of the integrals given in equations (1.1) and (1.2).

$s+\frac {1}{2}$

(see, for example, the form of the integrals given in equations (1.1) and (1.2).

We refer to the G-action on Y introduced in Theorem 2.2 as the middle G-action (in contrast with the left or right G-actions). The isomorphism

![]() $\nu $

in Theorem 2.2 is our answer to the questions posed above. That is,

$\nu $

in Theorem 2.2 is our answer to the questions posed above. That is,

![]() $\nu $

defines an isomorphism

$\nu $

defines an isomorphism

2.1.2 Compatibility with L-functions

The isomorphism

![]() $\nu $

above has one more remarkable property: it intertwines Godement–Jacquet and Jacquet–Langlands zeta integrals (and thus shows that these two methods give the same L-function). Explicitly, we make the following claim.

$\nu $

above has one more remarkable property: it intertwines Godement–Jacquet and Jacquet–Langlands zeta integrals (and thus shows that these two methods give the same L-function). Explicitly, we make the following claim.

Proposition 2.5. Let

![]() $\Psi \otimes f\in S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))\otimes _{\mathbb {C}} S(F^\times )=Y$

be the function

$\Psi \otimes f\in S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))\otimes _{\mathbb {C}} S(F^\times )=Y$

be the function

![]() $\Psi (g)f(y)$

, let

$\Psi (g)f(y)$

, let

![]() $\beta $

be a matrix coefficient of V, and let

$\beta $

be a matrix coefficient of V, and let

be the canonical isomorphism. Then

where

$$ \begin{align*} Z_{\text{JL}}\left(w,s\right) & =\int_{F^\times} w(y){\left|{y}\right|}^{s-\frac{1}{2}}{\,\mathrm{d}^\times\!{y}}, \\ Z_{\text{GJ}}\left(\beta,\Psi,s\right) & =\int_{{\mathrm{GL}}_2(F)} \beta(g)\Psi(g){\left|{\det(g)}\right|}^{s+\frac{1}{2}}{\,\mathrm{d}^\times\!{g}} \\ \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} Z_{\text{JL}}\left(w,s\right) & =\int_{F^\times} w(y){\left|{y}\right|}^{s-\frac{1}{2}}{\,\mathrm{d}^\times\!{y}}, \\ Z_{\text{GJ}}\left(\beta,\Psi,s\right) & =\int_{{\mathrm{GL}}_2(F)} \beta(g)\Psi(g){\left|{\det(g)}\right|}^{s+\frac{1}{2}}{\,\mathrm{d}^\times\!{g}} \\ \end{align*} $$

are the Jacquet–Langlands and Godement–Jacquet zeta integrals, respectively.

This will follow immediately from Remark 2.21 below.

Remark 2.6. With the language and tools developed in Section 3, we will be able to reformulate Theorem 2.2 in a much cleaner way, as well as give a slightly different proof.

Specifically, it will turn out that we can use the space Y to define a symmetric monoidal structure

![]() on the category of smooth G-modules. The essence of Theorem 2.2 is that generic irreducible representations are idempotent with respect to this monoidal structure. This will follow at once from the general principle that in an abelian symmetric monoidal category whose tensor product is right exact, surjections from the unit

on the category of smooth G-modules. The essence of Theorem 2.2 is that generic irreducible representations are idempotent with respect to this monoidal structure. This will follow at once from the general principle that in an abelian symmetric monoidal category whose tensor product is right exact, surjections from the unit

![]() turn V into an idempotent. This is essentially the same argument showing that for a commutative algebra A, module quotients of A are also algebra quotients of A. See Example 3.55 for details.

turn V into an idempotent. This is essentially the same argument showing that for a commutative algebra A, module quotients of A are also algebra quotients of A. See Example 3.55 for details.

2.2 The Weil representation

In this subsection, we will construct the middle action on Y, which we will use to prove Theorem 2.2. This is done by turning

![]() $S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))$

into a Weil representation for an appropriate metaplectic group. The action of the metaplectic group is then used to construct the hidden action on Y directly. Once this action is constructed, proving its properties is relatively straightforward. After proving Theorem 2.2, we will give a few additional remarks about the middle action and its properties.

$S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))$

into a Weil representation for an appropriate metaplectic group. The action of the metaplectic group is then used to construct the hidden action on Y directly. Once this action is constructed, proving its properties is relatively straightforward. After proving Theorem 2.2, we will give a few additional remarks about the middle action and its properties.

We begin by constructing the symplectic space which will give us the appropriate representation. The idea is to find a space such that

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)$

is a Lagrangian subspace of it.

$\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)$

is a Lagrangian subspace of it.

Recall that the pairing

![]() $(m,m')\mapsto \left <m,m'\right>={\mathrm {tr}}(m){\mathrm {tr}}(m')-{\mathrm {tr}}(mm')$

is the polarization (or multilinearization) of the quadratic map

$(m,m')\mapsto \left <m,m'\right>={\mathrm {tr}}(m){\mathrm {tr}}(m')-{\mathrm {tr}}(mm')$

is the polarization (or multilinearization) of the quadratic map

![]() $m\mapsto \det (m)$

on

$m\mapsto \det (m)$

on

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)$

.

$\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)$

.

Construction 2.7. Consider the vector space

![]() $U=\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)$

, and let W be a two-dimensional symplectic vector space. We turn

$U=\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)$

, and let W be a two-dimensional symplectic vector space. We turn

![]() $U\otimes W$

into a symplectic vector space via

$U\otimes W$

into a symplectic vector space via

In particular, we get a map

of the group

into the group of symplectic automorphisms of

![]() $U\otimes W$

. This embedding is defined by

$U\otimes W$

. This embedding is defined by

Remark 2.8. The construction of the space

![]() $U\otimes W$

above obfuscates the fact that the three terms in

$U\otimes W$

above obfuscates the fact that the three terms in

![]() $G^{3,\det =1}$

act on

$G^{3,\det =1}$

act on

![]() $U\otimes W$

symmetrically. Indeed, as a vector space,

$U\otimes W$

symmetrically. Indeed, as a vector space,

![]() $U\cong W\otimes W^\vee $

, and therefore one can exchange the factors of W in the product

$U\cong W\otimes W^\vee $

, and therefore one can exchange the factors of W in the product

![]() $U\otimes W\cong W\otimes W^\vee \otimes W$

. This is easily seen to leave the symplectic form invariant.

$U\otimes W\cong W\otimes W^\vee \otimes W$

. This is easily seen to leave the symplectic form invariant.

Construction 2.9. The map

![]() $G^{3,\det =1} \rightarrow \operatorname {\mathrm {Sp}}(U\otimes W)$

of Construction 2.7 can be extended to a map

$G^{3,\det =1} \rightarrow \operatorname {\mathrm {Sp}}(U\otimes W)$

of Construction 2.7 can be extended to a map

where

![]() $S_3$

acts by interchanging the order of the factors. In particular, we fix the convention that the transposition

$S_3$

acts by interchanging the order of the factors. In particular, we fix the convention that the transposition

![]() $(1,3)\in S_3$

acts by

$(1,3)\in S_3$

acts by

Recollection 2.10 (Weil representation of metaplectic group)

Let V be a symplectic vector space over F. The Heisenberg group

![]() $H(V)$

is defined as the underlying set

$H(V)$

is defined as the underlying set

![]() $V\times F$

, with multiplication given by

$V\times F$

, with multiplication given by

The group

![]() $H(V)$

has a unique (up to scalar automorphism) irreducible representation

$H(V)$

has a unique (up to scalar automorphism) irreducible representation

![]() $(\pi ,X)$

such that

$(\pi ,X)$

such that

![]() $(0,x)$

acts via any given nontrivial additive character

$(0,x)$

acts via any given nontrivial additive character

![]() $e{\,:\,} F\to {\mathbb {C}}^\times $

. For any symplectomorphism

$e{\,:\,} F\to {\mathbb {C}}^\times $

. For any symplectomorphism

![]() $g\in \operatorname {Sp}(V)$

, one can define the representation

$g\in \operatorname {Sp}(V)$

, one can define the representation

![]() $\pi ^g$

given by

$\pi ^g$

given by

![]() $\pi ^g(v,x)=\pi (g(v),x)$

. The group of pairs

$\pi ^g(v,x)=\pi (g(v),x)$

. The group of pairs

![]() $(g,\gamma )$

, where

$(g,\gamma )$

, where

![]() $g\in \operatorname {Sp}(V)$

and

$g\in \operatorname {Sp}(V)$

and

![]() $\gamma {\,:\,}\pi \to \pi ^g$

is an

$\gamma {\,:\,}\pi \to \pi ^g$

is an

![]() $H(V)$

-linear map is called the metaplectic group

$H(V)$

-linear map is called the metaplectic group

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Mp}}(V)$

. This group sits in an exact sequence

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Mp}}(V)$

. This group sits in an exact sequence

and it has a canonical representation on the space X, called the Weil representation.

For

![]() $L\subseteq V$

a Lagrangian subspace and a splitting

$L\subseteq V$

a Lagrangian subspace and a splitting

one can give an explicit model for this representation,

![]() $X=S(L)$

. Here,

$X=S(L)$

. Here,

![]() $S(L)$

is the space of smooth and compactly supported functions on L, with group action

$S(L)$

is the space of smooth and compactly supported functions on L, with group action

$$\begin{align*}\pi(v,x)\cdot \Psi(\ell)=e\left(-\left<v,\ell+\frac{1}{2}p(v)\right>+x\right)\cdot\Psi(\ell+p(v)) \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\pi(v,x)\cdot \Psi(\ell)=e\left(-\left<v,\ell+\frac{1}{2}p(v)\right>+x\right)\cdot\Psi(\ell+p(v)) \end{align*}$$

for

![]() $v\in V$

,

$v\in V$

,

![]() $\ell \in L$

,

$\ell \in L$

,

![]() $x\in F$

. This defines an action of

$x\in F$

. This defines an action of

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Mp}}(V)$

on

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Mp}}(V)$

on

![]() $S(L)$

, called the Schrödinger model of the Weil representation.

$S(L)$

, called the Schrödinger model of the Weil representation.

Construction 2.11. Consider the Lagrangian subspace

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)=\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)\otimes e_2\subseteq U\otimes W$

, where

$\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)=\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)\otimes e_2\subseteq U\otimes W$

, where

![]() $e_1,e_2\in W$

is a standard basis. We define a splitting split

$e_1,e_2\in W$

is a standard basis. We define a splitting split

![]() $U\otimes W\to \operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)$

with kernel

$U\otimes W\to \operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)$

with kernel

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)\otimes e_1$

. Then by the Schrödinger model of the Weil representation of

$\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)\otimes e_1$

. Then by the Schrödinger model of the Weil representation of

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Mp}}(U\otimes W)$

on

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Mp}}(U\otimes W)$

on

![]() $S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))$

corresponding to the character

$S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))$

corresponding to the character

![]() $e{\,:\,} F \rightarrow {\mathbb {C}}^\times $

, we get an action of the metaplectic group

$e{\,:\,} F \rightarrow {\mathbb {C}}^\times $

, we get an action of the metaplectic group

on

![]() $S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))$

.

$S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))$

.

Proposition 2.12. There is a unique lift

satisfying that the transposition

![]() $(1,3)\in S_3$

of the left and right actions acts on

$(1,3)\in S_3$

of the left and right actions acts on

![]() $S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))$

via the transposition

$S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))$

via the transposition

![]() $g\mapsto g^T$

of

$g\mapsto g^T$

of

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)$

.

$\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)$

.

For the sake of clarity of the exposition, we postpone the proof of this statement to the end of this subsection. Our proof will be constructive, and we will give an explicit description of this lift.

We conclude that the group

![]() $S_3\ltimes G^{3,\det =1}$

acts on

$S_3\ltimes G^{3,\det =1}$

acts on

![]() $S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))$

.

$S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))$

.

Finally, we can use this Weil representation to construct an additional G-action on Y.

Construction 2.13. We use induction with compact support to extend the action of

![]() $G^{3,\det =1}$

on

$G^{3,\det =1}$

on

![]() $S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))$

to an action of

$S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))$

to an action of

![]() $G^3$

on Y. Specifically, we identify

$G^3$

on Y. Specifically, we identify

via the section

given by

$y\mapsto \left (1,\begin {pmatrix}y & \\ & 1\end {pmatrix},1\right )$

, together with a determinant twist.

$y\mapsto \left (1,\begin {pmatrix}y & \\ & 1\end {pmatrix},1\right )$

, together with a determinant twist.

Explicitly, if

![]() $\Psi (m,y)=\Phi (m)f(y)\in S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)\times F^\times )$

for

$\Psi (m,y)=\Phi (m)f(y)\in S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F)\times F^\times )$

for

![]() $\Phi \in S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))$

and

$\Phi \in S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))$

and

![]() $f\in S(F^\times )$

, then we define

$f\in S(F^\times )$

, then we define

$$ \begin{align} & ((g_1,g_2,g_3)\cdot\Psi)(m,y) \notag \\ &\quad ={\left|{\det(g_1 g_2 g_3)}\right|}\cdot\left(\left(g_1,\begin{pmatrix}y & \\ & 1\end{pmatrix}g_2\begin{pmatrix}y^{-1}\det(g_1 g_2 g_3)^{-1} & \\ & 1\end{pmatrix},g_3\right)\cdot\Phi\right)(m) f(y\cdot\det(g_1 g_2 g_3)), \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} & ((g_1,g_2,g_3)\cdot\Psi)(m,y) \notag \\ &\quad ={\left|{\det(g_1 g_2 g_3)}\right|}\cdot\left(\left(g_1,\begin{pmatrix}y & \\ & 1\end{pmatrix}g_2\begin{pmatrix}y^{-1}\det(g_1 g_2 g_3)^{-1} & \\ & 1\end{pmatrix},g_3\right)\cdot\Phi\right)(m) f(y\cdot\det(g_1 g_2 g_3)), \end{align} $$

where the action of

$\left (g_1,\begin {pmatrix}y & \\ & 1\end {pmatrix}g_2\begin {pmatrix}y^{-1}\det (g_1 g_2 g_3)^{-1} & \\ & 1\end {pmatrix},g_3\right )$

on

$\left (g_1,\begin {pmatrix}y & \\ & 1\end {pmatrix}g_2\begin {pmatrix}y^{-1}\det (g_1 g_2 g_3)^{-1} & \\ & 1\end {pmatrix},g_3\right )$

on

![]() $\Phi $

is the Weil representation action.

$\Phi $

is the Weil representation action.

We refer to the resulting action of the middle copy of

![]() $G={\mathrm {GL}}_2(F)$

on Y as the middle action.

$G={\mathrm {GL}}_2(F)$

on Y as the middle action.

Recall that

![]() $g\mapsto g^{-T}$

is the Cartan involution on

$g\mapsto g^{-T}$

is the Cartan involution on

![]() ${\mathrm {GL}}_2(F)$

, given by the inverse of the transposition map:

${\mathrm {GL}}_2(F)$

, given by the inverse of the transposition map:

![]() $g^{-T}=(g^T)^{-1}$

.

$g^{-T}=(g^T)^{-1}$

.

Example 2.14. We can explicitly write down the action of

![]() $(g_1,1,g_3)$

on Y

$(g_1,1,g_3)$

on Y

This follows from the explicit construction in equations (2.5) and (2.9) in the proof of Proposition 2.12 below.

Example 2.15. As in Remark 2.8, there is a hidden symmetry between the left, right and middle G-actions on Y. This follows because Y carries an action of

![]() $S_3\ltimes G^3$

. In particular, the action of the the transposition

$S_3\ltimes G^3$

. In particular, the action of the the transposition

![]() $(1,3)\in S_3$

on Y is given by

$(1,3)\in S_3$

on Y is given by

as can be seen from equation (2.10) in the proof of Proposition 2.12 below.

Remark 2.16. In order to be consistent with the notation of Theorem 2.2, we need to be able to write expressions of the form

Recall that we are considering

![]() $\widetilde {V}$

to be a right-module. Therefore, we need to turn one of the G-actions on Y into a right action. In order to be consistent with equation (2.1), we will occasionally use the transposition

$\widetilde {V}$

to be a right-module. Therefore, we need to turn one of the G-actions on Y into a right action. In order to be consistent with equation (2.1), we will occasionally use the transposition

![]() $g\mapsto g^T$

to turn the third G-action into a right-action whenever it is necessary. See also Definition 3.2 below.

$g\mapsto g^T$

to turn the third G-action into a right-action whenever it is necessary. See also Definition 3.2 below.

We finish this subsection by proving Proposition 2.12.

Proof of Proposition 2.12

Let us begin by showing that there is at most one metaplectic lift for the map

![]() $S_3\ltimes G^{3,\det =1} \rightarrow \operatorname {\mathrm {Sp}}(U\otimes W)$

compatible with the specified action of the metaplectic lift of

$S_3\ltimes G^{3,\det =1} \rightarrow \operatorname {\mathrm {Sp}}(U\otimes W)$

compatible with the specified action of the metaplectic lift of

![]() $(1,3)$

. This follows because the abelianization of

$(1,3)$

. This follows because the abelianization of

![]() $S_3\ltimes G^{3,\det =1}$

is

$S_3\ltimes G^{3,\det =1}$

is

![]() ${\mathbb {Z}}/2$

and is generated by the image of the transposition

${\mathbb {Z}}/2$

and is generated by the image of the transposition

![]() $(1,3)$

due to the fact that any two lifts to

$(1,3)$

due to the fact that any two lifts to

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Mp}}(U\otimes W)$

differ by a character. Also, recall that the Weil representation is faithful for the metaplectic group so that describing lifts of elements of

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Mp}}(U\otimes W)$

differ by a character. Also, recall that the Weil representation is faithful for the metaplectic group so that describing lifts of elements of

![]() $S_3\ltimes G^{3,\det =1}$

is the same as describing their actions on

$S_3\ltimes G^{3,\det =1}$

is the same as describing their actions on

![]() $S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))$

.

$S(\operatorname {\mathrm {M}}_2(F))$

.

Let us show the existence of this lift. We will do so in several steps. Let us first show that the subgroup

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2(F)^3\subseteq S_3\ltimes G^{3,\det =1}$

admits a unique lift. We will then handle the rest of the group. Indeed, the lift of each factor

$\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2(F)^3\subseteq S_3\ltimes G^{3,\det =1}$

admits a unique lift. We will then handle the rest of the group. Indeed, the lift of each factor

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2(F)$

is unique because its abelianization is trivial. Note that the subgroup

$\operatorname {\mathrm {SL}}_2(F)$