1 Introduction

The decomposition of normed linear spaces into direct sums and the analysis of the associated projection operators is central to important chapters in the theory of modern and classical Banach spaces. In a seminal paper, Lindenstrauss [Reference Lindenstrauss23] set forth an influential research program aiming at detailed investigations of complemented subspaces and operators on Banach spaces.

The main question addressed by Lindenstrauss was this: Which are the spaces X that cannot be further decomposed into two `essentially different, infinite-dimensional subspaces'? That is to say, which are the Banach spaces X that are not isomorphic to the direct sum of two infinite-dimensional spaces Y and Z, where neither Y nor Z is isomorphic to X? This condition would be satisfied if X were indecomposable: that is, for any decomposition of X into two spaces, one of them has to be finite-dimensional. Separately, such a space could be primary, meaning that for any decomposition of X into two spaces, one of them has to be isomorphic to

![]() $X.$

The first example of an indecomposable Banach space was constructed by Gowers and Maurey [Reference Gowers and Maurey18], who also showed that their space

$X.$

The first example of an indecomposable Banach space was constructed by Gowers and Maurey [Reference Gowers and Maurey18], who also showed that their space

![]() $X_{\mathrm {GM}} $

is not primary – the infinite-dimensional component of

$X_{\mathrm {GM}} $

is not primary – the infinite-dimensional component of

![]() $X_{\mathrm {GM}} \sim X\oplus Y $

is not isomorphic to the whole space.

$X_{\mathrm {GM}} \sim X\oplus Y $

is not isomorphic to the whole space.

While indecomposable spaces play a tremendous role [Reference Argyros and Haydon3, Reference Gowers and Maurey18, Reference Maurey27] in the present-day study of nonclassical Banach spaces, a wide variety of Banach function spaces may usually be decomposed, for instance, by restriction to subsets, by taking conditional expectations, and so on. This provides the background for the program set forth by Lindenstrauss to determine the ‘classical’ spaces that are primary.

1.1 Background and history

The term ‘classical Banach space’ – while not formally defined – certainly applies to the space

![]() $C[0,1]$

and to scalar and vector-valued Lebesgue spaces. The space of continuous functions was shown to be primary by Lindenstrauss and Pełczyński [Reference Lindenstrauss and Pełczyński24], who posed the corresponding problem for scalar-valued

$C[0,1]$

and to scalar and vector-valued Lebesgue spaces. The space of continuous functions was shown to be primary by Lindenstrauss and Pełczyński [Reference Lindenstrauss and Pełczyński24], who posed the corresponding problem for scalar-valued

![]() $L_p$

spaces. Its elegant solution by Enflo via Maurey [Reference Maurey26] introduced a ground-breaking method of proof that applies equally well to each of the

$L_p$

spaces. Its elegant solution by Enflo via Maurey [Reference Maurey26] introduced a ground-breaking method of proof that applies equally well to each of the

![]() $L_ p $

spaces

$L_ p $

spaces

![]() $ (1 \le p < \infty )$

. Later alternative proofs were given by Alspach, Enflo and Odell [Reference Alspach, Enflo and Odell1] for

$ (1 \le p < \infty )$

. Later alternative proofs were given by Alspach, Enflo and Odell [Reference Alspach, Enflo and Odell1] for

![]() $L_p $

in the reflexive range

$L_p $

in the reflexive range

![]() $1<p<\infty $

and by Enflo and Starbird [Reference Enflo and Starbird16] for

$1<p<\infty $

and by Enflo and Starbird [Reference Enflo and Starbird16] for

![]() $L_1$

.

$L_1$

.

Exceptionally deep results on the decomposition of Bochner-Lebesgue spaces

![]() $L_p(X)$

are due to Capon [Reference Capon12, Reference Capon11], who obtained that those spaces are primary in the following cases:

$L_p(X)$

are due to Capon [Reference Capon12, Reference Capon11], who obtained that those spaces are primary in the following cases:

-

- X is a Banach space with a symmetric basis, and

$1 \le p < \infty $

.

$1 \le p < \infty $

. -

-

$ X = L_ q $

, where

$ X = L_ q $

, where

$ 1< q < \infty $

and

$ 1< q < \infty $

and

$ 1< p < \infty $

.

$ 1< p < \infty $

.

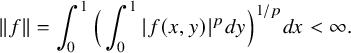

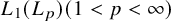

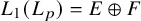

This leaves the spaces

![]() $ L_1(L_p) $

and

$ L_1(L_p) $

and

![]() $ L_p(L_1) $

among the most prominent examples of classical Banach spaces for which primariness is open.

$ L_p(L_1) $

among the most prominent examples of classical Banach spaces for which primariness is open.

After Capon’s paper [Reference Capon12], the focus was concentrated mostly on nonseparable Banach spaces, where Bourgain [Reference Bourgain7] developed a very flexible method based on localisation to a sequence of quantitative finite-dimensional factorisation problems. This method led to results like the primariness of

![]() $\mathcal {L}(\ell _2)$

[Reference Blower6] and the primariness of

$\mathcal {L}(\ell _2)$

[Reference Blower6] and the primariness of

![]() $\mathrm {BMO}$

and its predual

$\mathrm {BMO}$

and its predual

![]() $H_1$

by the third author [Reference Müller29].

$H_1$

by the third author [Reference Müller29].

The purpose of the present paper is to prove that

![]() $ L_1(L_p) $

is primary. Our proof works equally well for real and complex-valued functions. Before we describe our work, we review in some detail the development of methods pertaining to the spaces

$ L_1(L_p) $

is primary. Our proof works equally well for real and complex-valued functions. Before we describe our work, we review in some detail the development of methods pertaining to the spaces

![]() $L_p$

and, more broadly, to rearrangement-invariant spaces.

$L_p$

and, more broadly, to rearrangement-invariant spaces.

Projections on those spaces are studied effectively alongside the Haar system and the reproducing properties of its block bases. The methods developed for proving that a particular Lebesgue space

![]() $L_p$

is primary may be divided into two basic classes, depending on whether the Haar system is an unconditional Schauder basis.

$L_p$

is primary may be divided into two basic classes, depending on whether the Haar system is an unconditional Schauder basis.

In case of unconditionality, the most flexible method goes back to the work of Alspach, Enflo and Odell [Reference Alspach, Enflo and Odell1]. For a linear operator T on

![]() $L_p $

, it yields a block basis of the Haar system

$L_p $

, it yields a block basis of the Haar system

![]() $\widetilde {h}_I $

and a bounded sequence of scalars

$\widetilde {h}_I $

and a bounded sequence of scalars

![]() $a_I $

forming an approximate eigensystem of T such that

$a_I $

forming an approximate eigensystem of T such that

and

![]() $\widetilde {h}_I$

spans a complemented copy of the space

$\widetilde {h}_I$

spans a complemented copy of the space

![]() $L_p $

. Thus, when restricted to

$L_p $

. Thus, when restricted to

![]() $ span \widetilde {h}_I$

, the operator T acts as a bounded Haar multiplier. Since the Haar basis is unconditional, the Haar multiplier is invertible if

$ span \widetilde {h}_I$

, the operator T acts as a bounded Haar multiplier. Since the Haar basis is unconditional, the Haar multiplier is invertible if

![]() $ |a_I |> \delta $

for some

$ |a_I |> \delta $

for some

![]() $\delta> 0. $

$\delta> 0. $

Alspach, Enflo and Odell [Reference Alspach, Enflo and Odell1] arrive at equation (1) by ensuring that for

![]() $\varepsilon _{I, J }> 0 $

sufficiently small, the following linearly ordered set of constraints holds true

$\varepsilon _{I, J }> 0 $

sufficiently small, the following linearly ordered set of constraints holds true

where the relation

![]() $\prec $

refers to the lexicographic order on the collection of dyadic intervals. Utilising that the independent

$\prec $

refers to the lexicographic order on the collection of dyadic intervals. Utilising that the independent

![]() $\{-1,+1\}$

-valued Rademacher system

$\{-1,+1\}$

-valued Rademacher system

![]() $\{r_n\}$

is a weak null sequence in

$\{r_n\}$

is a weak null sequence in

![]() $L_p$

,

$L_p$

,

![]() $(1 \le p < \infty )$

, Alspach, Enflo and Odell [Reference Alspach, Enflo and Odell1] obtain, by induction along

$(1 \le p < \infty )$

, Alspach, Enflo and Odell [Reference Alspach, Enflo and Odell1] obtain, by induction along

![]() $\prec $

, the block basis

$\prec $

, the block basis

![]() $ \widetilde {h}_I$

satisfying equation (2).

$ \widetilde {h}_I$

satisfying equation (2).

The Alspach-Enflo-Odell method provides the basic model for the study of operators on function spaces in which the Haar system is unconditional; this applies in particular to rearrangement of invariant spaces in [Reference Johnson, Maurey, Schechtman and Tzafriri20] and [Reference Dosev, Johnson and Schechtman15].

In

![]() $L_1 $

, the Haar system is a Schauder basis but fails to be unconditional. The basic methods for proving that

$L_1 $

, the Haar system is a Schauder basis but fails to be unconditional. The basic methods for proving that

![]() $L_1 $

is primary are due to Enflo via Maurey [Reference Maurey26] on the one hand and Enflo and Starbird [Reference Enflo and Starbird16] on the other hand. For operators T on

$L_1 $

is primary are due to Enflo via Maurey [Reference Maurey26] on the one hand and Enflo and Starbird [Reference Enflo and Starbird16] on the other hand. For operators T on

![]() $L_1 $

, the Enflo-Maurey method yields a block basis of the Haar basis

$L_1 $

, the Enflo-Maurey method yields a block basis of the Haar basis

![]() $\widetilde {h}_I $

and a bounded measurable function g, such that

$\widetilde {h}_I $

and a bounded measurable function g, such that

for

![]() $ f \in \mathrm {span}\{ \widetilde {h}_I\}$

, and

$ f \in \mathrm {span}\{ \widetilde {h}_I\}$

, and

![]() $\widetilde {h}_I$

spans a copy of

$\widetilde {h}_I$

spans a copy of

![]() $L_1 $

. Thus the restricted operator T acts as a bounded multiplication operator and is invertible if

$L_1 $

. Thus the restricted operator T acts as a bounded multiplication operator and is invertible if

![]() $ |g |> \delta $

for some

$ |g |> \delta $

for some

![]() $\delta> 0. $

The full strength of the proof by Enflo-Maurey is applied to show that the representation in equation (3) holds true.

$\delta> 0. $

The full strength of the proof by Enflo-Maurey is applied to show that the representation in equation (3) holds true.

Enflo-Maurey [Reference Maurey26] exhibit in their proof of equation (3) a sequence of bounded scalars

![]() $a_I $

such that

$a_I $

such that

Since the Rademacher system

![]() $\{r_n\}$

is a weakly null sequence in

$\{r_n\}$

is a weakly null sequence in

![]() $L_1$

, equation (4) may be obtained directly by choosing a block basis for which the constraints in equation (2) and

$L_1$

, equation (4) may be obtained directly by choosing a block basis for which the constraints in equation (2) and

hold true. Remarkably, until very recently [Reference Lechner, Motakis, Müller and Schlumprecht22], eigensystem representations such as equation (4) were not exploited in the context of

![]() $L ^1 $

, where the Haar system is not unconditional.

$L ^1 $

, where the Haar system is not unconditional.

The powerful precision of

![]() $L_1$

-constructions with dyadic martingales and block basis of the Haar system is in full display in [Reference Johnson, Maurey and Schechtman19] and [Reference Talagrand36]. Johnson, Maurey and Schechtman [Reference Johnson, Maurey and Schechtman19] determined a normalised weakly null sequence in

$L_1$

-constructions with dyadic martingales and block basis of the Haar system is in full display in [Reference Johnson, Maurey and Schechtman19] and [Reference Talagrand36]. Johnson, Maurey and Schechtman [Reference Johnson, Maurey and Schechtman19] determined a normalised weakly null sequence in

![]() $L_1 $

such that each of its infinite subsequences contains in its span a block basis of the Haar system

$L_1 $

such that each of its infinite subsequences contains in its span a block basis of the Haar system

![]() $\widetilde {h}_I$

, spanning a copy of

$\widetilde {h}_I$

, spanning a copy of

![]() $L_1. $

Thus

$L_1. $

Thus

![]() $L_1 $

fails to satisfy the unconditional subsequence property, a problem posed by Maurey and Rosenthal [Reference Maurey and Rosenthal28]. By contrast, Talagrand [Reference Talagrand36] constructed a dyadic martingale difference sequence

$L_1 $

fails to satisfy the unconditional subsequence property, a problem posed by Maurey and Rosenthal [Reference Maurey and Rosenthal28]. By contrast, Talagrand [Reference Talagrand36] constructed a dyadic martingale difference sequence

![]() $g_{n,k} $

such that neither

$g_{n,k} $

such that neither

![]() $X = \overline {\mathrm {span}\, }^{L_1} \{ g_{n,k} \}$

nor

$X = \overline {\mathrm {span}\, }^{L_1} \{ g_{n,k} \}$

nor

![]() $L_1/X$

contains a copy of

$L_1/X$

contains a copy of

![]() $L_1$

.

$L_1$

.

The investigation of complemented subspaces in Bochner Lebesgue spaces was initiated by Capon [Reference Capon12, Reference Capon11] who pushed hard to further the development of the scalar methods and proved that

![]() $L_p(X) (1\le p < \infty )$

is primary when X is a Banach space with a symmetric basis, say

$L_p(X) (1\le p < \infty )$

is primary when X is a Banach space with a symmetric basis, say

![]() $(x_{k}) .$

Specifically, Capon [Reference Capon12] showed that for an operator T on

$(x_{k}) .$

Specifically, Capon [Reference Capon12] showed that for an operator T on

![]() $L_p(X)$

, there exists a block basis of the Haar basis

$L_p(X)$

, there exists a block basis of the Haar basis

![]() $\widetilde {h}_I $

, a subsequence of the symmetric basis

$\widetilde {h}_I $

, a subsequence of the symmetric basis

![]() $(x_{k_n}) $

and a bounded measurable g such that

$(x_{k_n}) $

and a bounded measurable g such that

for

![]() $ f \in \mathrm {span} \{\widetilde {h}_I \}$

. Thus on

$ f \in \mathrm {span} \{\widetilde {h}_I \}$

. Thus on

![]() $ \mathrm {span} \{\widetilde {h}_I \} \otimes \mathrm {span} \{x_{k_n}\}$

the operator T acts like

$ \mathrm {span} \{\widetilde {h}_I \} \otimes \mathrm {span} \{x_{k_n}\}$

the operator T acts like

![]() $M_g \otimes Id $

, where

$M_g \otimes Id $

, where

![]() $M_g $

is the multiplication operator induced by

$M_g $

is the multiplication operator induced by

![]() $g. $

Simultaneously, Capon shows that the tensor products form an approximate eigensystem,

$g. $

Simultaneously, Capon shows that the tensor products form an approximate eigensystem,

where

![]() $ a_{I }$

is a bounded sequence of scalars and

$ a_{I }$

is a bounded sequence of scalars and

![]() $\widetilde {h}_I$

spans a copy of

$\widetilde {h}_I$

spans a copy of

![]() $L_p $

.

$L_p $

.

In the mixed norm space

![]() $L_p (L_ q) $

where

$L_p (L_ q) $

where

![]() $ 1< q < \infty $

and

$ 1< q < \infty $

and

![]() $ 1< p < \infty $

, the biparameter Haar system forms an unconditional basis. Displaying extraordinary combinatorial strength, Capon [Reference Capon11] exhibited a so-called local product block basis

$ 1< p < \infty $

, the biparameter Haar system forms an unconditional basis. Displaying extraordinary combinatorial strength, Capon [Reference Capon11] exhibited a so-called local product block basis

![]() $ k_{I \times J }$

spanning a complemented copy of

$ k_{I \times J }$

spanning a complemented copy of

![]() $L_p (L_q ) $

such that

$L_p (L_q ) $

such that

1.2 The present paper

Now we describe the main ideas in the approach of the present paper.

Introducing a transitive relation between operators

![]() $S,T$

on a Banach space X, we say that T is a projectional factor of S if there exist transfer operators

$S,T$

on a Banach space X, we say that T is a projectional factor of S if there exist transfer operators

![]() $ A, B \colon X \to X $

such that

$ A, B \colon X \to X $

such that

If merely

![]() $S = ATB$

, without the additional constraint

$S = ATB$

, without the additional constraint

![]() $BA =Id_X$

, we say that T is a factor of S, or equivalently that S factors through T.

$BA =Id_X$

, we say that T is a factor of S, or equivalently that S factors through T.

Clearly, if T is a projectional factor of S and S one of R, then T is a projectional factor of R: that is, being a projectional factor is a transitive relation. Given any operator

![]() $T : L_1(L_p) \to L_1(L_p)$

, the goal is to show that either T or

$T : L_1(L_p) \to L_1(L_p)$

, the goal is to show that either T or

![]() $Id -T$

is a factor of the identity

$Id -T$

is a factor of the identity

![]() $Id : L_1(L_p) \to L_1(L_p)$

. In section 2.1, we expand on the quantitative aspects of the transitive relation in equation (6) and the role it plays in providing a step-by-step reduction of the problem, allowing for the replacement of a given operator with a simpler one that is easier to work with.

$Id : L_1(L_p) \to L_1(L_p)$

. In section 2.1, we expand on the quantitative aspects of the transitive relation in equation (6) and the role it plays in providing a step-by-step reduction of the problem, allowing for the replacement of a given operator with a simpler one that is easier to work with.

Let

![]() $T : L_1(L_p) \to L_1(L_p)$

be a bounded linear operator. It is represented by a matrix

$T : L_1(L_p) \to L_1(L_p)$

be a bounded linear operator. It is represented by a matrix

![]() $T = ( T^{I,J})$

of operators

$T = ( T^{I,J})$

of operators

![]() $ T^{I,J} : L_1 \to L_1 $

, indexed by pairs of dyadic intervals

$ T^{I,J} : L_1 \to L_1 $

, indexed by pairs of dyadic intervals

![]() $(I,J)$

: that is, on

$(I,J)$

: that is, on

![]() $f \in L_1(L_p)$

with Haar expansion

$f \in L_1(L_p)$

with Haar expansion

the operator T acts by

Theorem 6.1, the main result of this paper, asserts that there exists a bounded operator

![]() $ T^{0} :L_1 \to L_1 $

such that

$ T^{0} :L_1 \to L_1 $

such that

meaning there exist bounded transfer operators

![]() $A, B : L_1(L_p) \to L_1(L_p) $

such that

$A, B : L_1(L_p) \to L_1(L_p) $

such that

![]() $ B A = Id _{L_1(L_p)} $

and

$ B A = Id _{L_1(L_p)} $

and

The ideas involved in the proof of Theorem 6.1 are based on the interplay of topological, geometric and probabilistic principles. Specifically, we build on compact families of

![]() $L_1 $

-operators, extracted from

$L_1 $

-operators, extracted from

![]() $ span \{ T^{I,J} \} $

, and large deviation estimates for empirical processes:

$ span \{ T^{I,J} \} $

, and large deviation estimates for empirical processes:

-

(a) (Compactness.) We utilise the Semenov-Uksusov characterisation [Reference Semenov and Uksusov34, Reference Semenov and Uksusov35] of Haar multipliers on

$L_1 $

and uncover compactness properties of the operators

$L_1 $

and uncover compactness properties of the operators

$ T^{I,J} : L_1 \to L_1 $

. See Theorem 3.2 and Theorem 3.4.

$ T^{I,J} : L_1 \to L_1 $

. See Theorem 3.2 and Theorem 3.4. -

(b) (Stabilisation.) Large deviation estimates for the empirical distribution method gave rise to a novel connection between factorisation problems on

$L_ 1 (L_p) $

and the concentration of measure phenomenon. See Lemma 5.3 and Lemma 5.4.

$L_ 1 (L_p) $

and the concentration of measure phenomenon. See Lemma 5.3 and Lemma 5.4.

Step 1. We say that T is a diagonal operator if

![]() $ T^{I,J} = 0$

for

$ T^{I,J} = 0$

for

![]() $ I \neq J , $

in which case we put

$ I \neq J , $

in which case we put

![]() $ T^{L} =T^{L,L}$

. The first step provides the reduction to diagonal operators. Specifically, Theorem 4.1 asserts that for any operator

$ T^{L} =T^{L,L}$

. The first step provides the reduction to diagonal operators. Specifically, Theorem 4.1 asserts that for any operator

![]() $T = ( T^{I,J})$

, there exists a diagonal operator

$T = ( T^{I,J})$

, there exists a diagonal operator

![]() $T_{\mathrm {diag}} =( T^{L} )$

such that

$T_{\mathrm {diag}} =( T^{L} )$

such that

The reduction in equation (10) results from compactness properties for the family of

![]() $L_1 $

operators

$L_1 $

operators

![]() $ T^{I,J}$

established in Theorem 3.2 and Theorem 3.4. Specifically, if

$ T^{I,J}$

established in Theorem 3.2 and Theorem 3.4. Specifically, if

![]() $ f \in L_1$

, then the set

$ f \in L_1$

, then the set

if, moreover,

![]() $T^{I,J}$

satisfies uniform off-diagonal estimates

$T^{I,J}$

satisfies uniform off-diagonal estimates

then, for

![]() $ \eta> 0 ,$

there exists a stopping time collection of dyadic intervals

$ \eta> 0 ,$

there exists a stopping time collection of dyadic intervals

![]() $ \mathcal {A}$

satisfying

$ \mathcal {A}$

satisfying

![]() $|\limsup \mathcal {A}|> 1 -\eta $

such that the set of operators

$|\limsup \mathcal {A}|> 1 -\eta $

such that the set of operators

Recall that

![]() $ \mathcal {A} \subseteq \mathcal {D}$

is a stopping time collection if for

$ \mathcal {A} \subseteq \mathcal {D}$

is a stopping time collection if for

![]() $K, L \in \mathcal {A} $

and

$K, L \in \mathcal {A} $

and

![]() $ J \in \mathcal {D} $

, the assumption

$ J \in \mathcal {D} $

, the assumption

![]() $ K \subset J \subset L $

implies that

$ K \subset J \subset L $

implies that

![]() $ J \in \mathcal {A} .$

By Theorem 2.6, the orthogonal projection

$ J \in \mathcal {A} .$

By Theorem 2.6, the orthogonal projection

is bounded on

![]() $L_1 $

when

$L_1 $

when

![]() $ \mathcal {A} $

is a stopping time collection of dyadic intervals.

$ \mathcal {A} $

is a stopping time collection of dyadic intervals.

Step 2. Next we show that it suffices to prove the factorisation in equation (9) for diagonal operators satisfying uniform off-diagonal estimates. We say that

![]() $ T = (R^{L}) $

is a reduced diagonal operator if the

$ T = (R^{L}) $

is a reduced diagonal operator if the

![]() $R^L : L_1 \to L_1 $

satisfy

$R^L : L_1 \to L_1 $

satisfy

Proposition 5.6 asserts that there exists a reduced diagonal operator

![]() $ T^{\mathrm {red}}_{\mathrm {diag}} = (R^{L}) $

satisfying equation (14), such that

$ T^{\mathrm {red}}_{\mathrm {diag}} = (R^{L}) $

satisfying equation (14), such that

To prove equation (15), we use the compactness properties of

![]() $T_{\mathrm {diag}} = (T^{L}) $

together with measure concentration estimates [Reference Bourgain, Lindenstrauss and Milman8, Reference Schechtman33] associated to the empirical distribution method. See Lemma 5.3 and Lemma 5.4.

$T_{\mathrm {diag}} = (T^{L}) $

together with measure concentration estimates [Reference Bourgain, Lindenstrauss and Milman8, Reference Schechtman33] associated to the empirical distribution method. See Lemma 5.3 and Lemma 5.4.

Step 3. Next we show that we may replace reduced diagonal operators by stable diagonal operators. We say that

![]() $ T^{\mathrm {stbl}}_{\mathrm {diag}} = (S^{L}) $

is a stable diagonal operator if

$ T^{\mathrm {stbl}}_{\mathrm {diag}} = (S^{L}) $

is a stable diagonal operator if

for dyadic intervals

![]() $M, L $

satisfying

$M, L $

satisfying

![]() $ L \subseteq M$

, we obtain in Proposition 5.2 that for any reduced diagonal operator

$ L \subseteq M$

, we obtain in Proposition 5.2 that for any reduced diagonal operator

![]() $ T^{\mathrm {red}}_{\mathrm {diag}} $

, there exists a stable diagonal operator

$ T^{\mathrm {red}}_{\mathrm {diag}} $

, there exists a stable diagonal operator

![]() $ T^{\mathrm {stbl}}_{\mathrm {diag}} $

such that

$ T^{\mathrm {stbl}}_{\mathrm {diag}} $

such that

We verify equation (17), exploiting again the compactness properties of

![]() $T^{\mathrm {red}}_{\mathrm {diag}} = (R^{L}) $

in tandem with the probabilistic estimates of Lemma 5.3 and Lemma 5.4.

$T^{\mathrm {red}}_{\mathrm {diag}} = (R^{L}) $

in tandem with the probabilistic estimates of Lemma 5.3 and Lemma 5.4.

Step 4. Proposition 6.2 provides the final step of the argument. It asserts that for any stable diagonal operator

![]() $ T^{\mathrm {stbl}}_{\mathrm {diag}} =(S^L)$

, there exists a bounded operator

$ T^{\mathrm {stbl}}_{\mathrm {diag}} =(S^L)$

, there exists a bounded operator

![]() $ T^{0} :L_1 \to L_1 $

such that

$ T^{0} :L_1 \to L_1 $

such that

To prove equation (18), we set up a telescoping chain of operators connecting any of the

![]() $ S^L $

to

$ S^L $

to

![]() $S^{[0,1]} $

and invoke the stability estimates in equation (16) available for the operators

$S^{[0,1]} $

and invoke the stability estimates in equation (16) available for the operators

![]() $S^I $

when

$S^I $

when

![]() $ L \subset I \subset [0,1]. $

Thus we may finally take

$ L \subset I \subset [0,1]. $

Thus we may finally take

![]() $T^0 = S^{[0,1]} .$

$T^0 = S^{[0,1]} .$

Step 5. Retracing our steps, taking into account that the notion of projectional factors forms a transitive relation, yields equation (9).

2 Preliminaries

2.1 Factors and projectional factors up to approximation

A common strategy in proving the primariness of spaces such as

![]() $L_p$

is to study the behaviour of a bounded linear operator on a

$L_p$

is to study the behaviour of a bounded linear operator on a

![]() $\sigma $

-subalgebra on a subset of

$\sigma $

-subalgebra on a subset of

![]() $[0,1)$

of positive measure. This process may have to be repeated several times. We introduce some language that will make this process notationally easier.

$[0,1)$

of positive measure. This process may have to be repeated several times. We introduce some language that will make this process notationally easier.

Definition 2.1. Let X be a Banach space,

![]() $T,S:X\to X$

be bounded linear operators and

$T,S:X\to X$

be bounded linear operators and

![]() $C\geq 1$

,

$C\geq 1$

,

![]() $\varepsilon \geq 0$

.

$\varepsilon \geq 0$

.

-

(a) We say that T is a C-factor of S with error

$\varepsilon $

if there exist

$\varepsilon $

if there exist

$A,B:X\to X$

with

$A,B:X\to X$

with

$\|BTA-S\| \leq \varepsilon $

and

$\|BTA-S\| \leq \varepsilon $

and

$\|A\|\|B\|\leq C$

. We may also say that

$\|A\|\|B\|\leq C$

. We may also say that

$S C$

-factors through Twith error

$S C$

-factors through Twith error

$\varepsilon $

.

$\varepsilon $

. -

(b) We say that T is a C-projectional factor of S with error

$\varepsilon $

if there exists a complemented subspace Y of X that is isomorphic to X with associated projection and isomorphism

$\varepsilon $

if there exists a complemented subspace Y of X that is isomorphic to X with associated projection and isomorphism

$P,A:X\to Y$

(i.e.,

$P,A:X\to Y$

(i.e.,

$A^{-1} P A$

is the identity on X), so that

$A^{-1} P A$

is the identity on X), so that

$\|A^{-1}PTA - S\| \leq \varepsilon $

and

$\|A^{-1}PTA - S\| \leq \varepsilon $

and

$\|A\|\|A^{-1}P\|\leq C$

. We may also say that

$\|A\|\|A^{-1}P\|\leq C$

. We may also say that

$S C$

-projectionally factors through Twith error

$S C$

-projectionally factors through Twith error

$\varepsilon $

.

$\varepsilon $

.

When the error is

![]() $\varepsilon = 0$

, we will simply say that T is a C-factor or C-projectional factor of S.

$\varepsilon = 0$

, we will simply say that T is a C-factor or C-projectional factor of S.

Remark 2.2. If T is a C-projectional factor of S with error

![]() $\varepsilon $

, then

$\varepsilon $

, then

![]() $I-T$

is a C-projectional factor of

$I-T$

is a C-projectional factor of

![]() $I-S$

with error

$I-S$

with error

![]() $\varepsilon $

. Indeed, if P and A are as in Definition (b), then

$\varepsilon $

. Indeed, if P and A are as in Definition (b), then

![]() $PA = A$

and therefore

$PA = A$

and therefore

![]() $A^{-1}P(I-T)A = I - A^{-1}PTA$

: that is,

$A^{-1}P(I-T)A = I - A^{-1}PTA$

: that is,

![]() $\|A^{-1}P(I-T)A - (I-S)\| \leq \varepsilon $

.

$\|A^{-1}P(I-T)A - (I-S)\| \leq \varepsilon $

.

In a certain sense, being an approximate factor or projectional factor is a transitive property.

Proposition 2.3. Let X be a Banach space and

![]() $R,S,T:X\to X$

be bounded linear operators.

$R,S,T:X\to X$

be bounded linear operators.

-

(a) If T is a C-factor of S with error

$\varepsilon $

and S is a D-factor of R with error

$\varepsilon $

and S is a D-factor of R with error

$\delta $

, then T is a

$\delta $

, then T is a

$CD$

-factor of R with error

$CD$

-factor of R with error

$D\varepsilon +\delta $

.

$D\varepsilon +\delta $

. -

(b) If T is a C-projectional factor of S with error

$\varepsilon $

and S is a D-projectional factor of R with error

$\varepsilon $

and S is a D-projectional factor of R with error

$\delta $

, then T is a

$\delta $

, then T is a

$CD$

-projectional factor or R with error

$CD$

-projectional factor or R with error

$D\varepsilon +\delta $

.

$D\varepsilon +\delta $

.

Proof. The first statement is straightforward, and thus we only provide a proof of the second one. Let Y and Z be complemented subspaces of X, which are isomorphic to X. Let

![]() $P:X\to Y$

and

$P:X\to Y$

and

![]() $Q:X\to Z$

be the associated projections, and

$Q:X\to Z$

be the associated projections, and

![]() $A:X\to Y$

and

$A:X\to Y$

and

![]() $B:X\to Z$

the associated isomorphisms satisfying

$B:X\to Z$

the associated isomorphisms satisfying

![]() $\|A\|\|A^{-1}P\| \leq C$

,

$\|A\|\|A^{-1}P\| \leq C$

,

![]() $\|B\|\|B^{-1}Q\|\leq D$

.

$\|B\|\|B^{-1}Q\|\leq D$

.

![]() $\|A^{-1}PT - S\| \leq \varepsilon $

and

$\|A^{-1}PT - S\| \leq \varepsilon $

and

![]() $\|B^{-1}QSB - R\| \leq \delta $

.

$\|B^{-1}QSB - R\| \leq \delta $

.

We define

![]() $\tilde P = AQA^{-1}P$

and

$\tilde P = AQA^{-1}P$

and

![]() $\tilde A = AB$

. Then

$\tilde A = AB$

. Then

![]() $\tilde P$

is a projection onto

$\tilde P$

is a projection onto

![]() $\tilde A[X]$

and

$\tilde A[X]$

and

![]() $\|\tilde P\|\|\tilde A^{-1}P\| \leq CD$

. We obtain

$\|\tilde P\|\|\tilde A^{-1}P\| \leq CD$

. We obtain

and thus

![]() $\|B^{-1}QA^{-1}PTAB - R\| \leq D\varepsilon +\delta $

. Finally, observe that

$\|B^{-1}QA^{-1}PTAB - R\| \leq D\varepsilon +\delta $

. Finally, observe that

and thus

![]() $\|\tilde A^{-1}\tilde PT\tilde A - R\|\leq D\varepsilon + \delta $

.

$\|\tilde A^{-1}\tilde PT\tilde A - R\|\leq D\varepsilon + \delta $

.

The following explains the relation between primariness and approximate projectional factors.

Proposition 2.4. Let X be a Banach space that satisfies Pełczyński’s accordion property: that is, for some

![]() $1\leq p\leq \infty $

, we have that

$1\leq p\leq \infty $

, we have that

![]() $X\simeq \ell _p(X)$

. Assume that there exist

$X\simeq \ell _p(X)$

. Assume that there exist

![]() $C\geq 1$

and

$C\geq 1$

and

![]() $0<\varepsilon <1/2$

so that every bounded linear operator

$0<\varepsilon <1/2$

so that every bounded linear operator

![]() $T:X\to X$

is a C-projectional factor with error

$T:X\to X$

is a C-projectional factor with error

![]() $\varepsilon $

of a scalar operator: that is, a scalar multiple of the identity. Then for every bounded linear operator

$\varepsilon $

of a scalar operator: that is, a scalar multiple of the identity. Then for every bounded linear operator

![]() $T:X\to X$

, the identity

$T:X\to X$

, the identity

![]() $2C/(1-2\varepsilon )$

factors through either T or

$2C/(1-2\varepsilon )$

factors through either T or

![]() $I-T$

. In particular, X is primary.

$I-T$

. In particular, X is primary.

Proof. Let Y be a subspace of X that is isomorphic to X and complemented in X, with associated projection and isomorphism

![]() $P,A:X\to Y$

, so that

$P,A:X\to Y$

, so that

![]() $\|A^{-1}P\|\|A\|\leq C$

and so that there exists a scalar

$\|A^{-1}P\|\|A\|\leq C$

and so that there exists a scalar

![]() $\lambda $

with

$\lambda $

with

![]() $\|(A^{-1}P)TA - \lambda I\| \leq \varepsilon $

. If

$\|(A^{-1}P)TA - \lambda I\| \leq \varepsilon $

. If

![]() $|\lambda | \geq 1/2$

, then

$|\lambda | \geq 1/2$

, then

$$\begin{align*}\big\|\underbrace{\lambda^{-1}A^{-1}PTA}_{=:B} - I\big\| \leq 2\varepsilon <1\end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\big\|\underbrace{\lambda^{-1}A^{-1}PTA}_{=:B} - I\big\| \leq 2\varepsilon <1\end{align*}$$

and thus

![]() $B^{-1}$

exists with

$B^{-1}$

exists with

![]() $\|B^{-1}\| \leq 1/(1-2\varepsilon )$

. We obtain that if

$\|B^{-1}\| \leq 1/(1-2\varepsilon )$

. We obtain that if

![]() $S = B^{-1}\lambda ^{-1}A^{-1}P$

, then

$S = B^{-1}\lambda ^{-1}A^{-1}P$

, then

![]() $STA = I$

and

$STA = I$

and

![]() $\|S\|\|A\| \leq 2C/(1-2\varepsilon )$

. If, on the other hand

$\|S\|\|A\| \leq 2C/(1-2\varepsilon )$

. If, on the other hand

![]() $|\lambda | <1/2$

, then, because

$|\lambda | <1/2$

, then, because

![]() $\|A^{-1}P(I-T)A - (1-\lambda )I\|\leq \varepsilon $

, we achieve the same conclusion for

$\|A^{-1}P(I-T)A - (1-\lambda )I\|\leq \varepsilon $

, we achieve the same conclusion for

![]() $I-T$

instead of T.

$I-T$

instead of T.

If

![]() $X = Y\oplus Z$

and

$X = Y\oplus Z$

and

![]() $Q:X\to Y$

is a projection, then we deduce that either Y or Z contains a complemented subspace isomorphic to X. To see that we can assume that for some scalar

$Q:X\to Y$

is a projection, then we deduce that either Y or Z contains a complemented subspace isomorphic to X. To see that we can assume that for some scalar

![]() $\lambda $

, with

$\lambda $

, with

![]() $|\lambda |\ge 1/2$

, Q is a C-projectional factor with error

$|\lambda |\ge 1/2$

, Q is a C-projectional factor with error

![]() $\varepsilon \in (0,1/2)$

of

$\varepsilon \in (0,1/2)$

of

![]() $\lambda I$

. Otherwise, we replace Q by

$\lambda I$

. Otherwise, we replace Q by

![]() $I-Q$

. From what we have proved so far, we deduce that there are operators

$I-Q$

. From what we have proved so far, we deduce that there are operators

![]() $S,A :X\to X$

so that

$S,A :X\to X$

so that

![]() $SQA = I$

. Then

$SQA = I$

. Then

![]() $W = QA(X)$

is a subspace of Y that is isomorphic to X. It is also complemented via the projection

$W = QA(X)$

is a subspace of Y that is isomorphic to X. It is also complemented via the projection

![]() $R = (S|_W)^{-1}S:X\to W$

. So we obtain that Y is a complemented subspace of X and X is isomorphic to complemented subspace of Y. Since in addition X satisfies the accordion property, it follows from Pełczyński’s famous classical argument from [Reference Pełczyński30] that

$R = (S|_W)^{-1}S:X\to W$

. So we obtain that Y is a complemented subspace of X and X is isomorphic to complemented subspace of Y. Since in addition X satisfies the accordion property, it follows from Pełczyński’s famous classical argument from [Reference Pełczyński30] that

![]() $X\simeq Y$

. Similarly, if

$X\simeq Y$

. Similarly, if

![]() $(I-Q)$

is a factor of the identity, we deduce

$(I-Q)$

is a factor of the identity, we deduce

![]() $X\simeq Z$

.

$X\simeq Z$

.

At this point, it is appropriate to point out that the above proposition applies to the space

![]() $L_1(X)$

for any Banach space X. Indeed,

$L_1(X)$

for any Banach space X. Indeed,

![]() $L_1(X)$

is isomorphic to an

$L_1(X)$

is isomorphic to an

![]() $\ell _1$

sum of infinitely many copies of itself (see, e.g., [Reference Wojtaszczyk41, Example 22(a), page 44]).

$\ell _1$

sum of infinitely many copies of itself (see, e.g., [Reference Wojtaszczyk41, Example 22(a), page 44]).

2.2 The Haar system in

$L_1$

$L_1$

We denote by

![]() $L_1$

the space of all (equivalence classes of) integrable scalar functions f with domain

$L_1$

the space of all (equivalence classes of) integrable scalar functions f with domain

![]() $[0,1)$

endowed with the norm

$[0,1)$

endowed with the norm

![]() $\|f\|_1 = \int _0^1|f(s)| ds$

. We will denote the Lebesgue measure of a measurable subset A of

$\|f\|_1 = \int _0^1|f(s)| ds$

. We will denote the Lebesgue measure of a measurable subset A of

![]() $[0,1)$

by

$[0,1)$

by

![]() $|A|$

.

$|A|$

.

We denote by

![]() $\mathcal {D}$

the collection of all dyadic intervals in

$\mathcal {D}$

the collection of all dyadic intervals in

![]() $[0,1)$

, namely

$[0,1)$

, namely

We define the bijective function

![]() $\iota : \mathcal {D}\to \{2,3,\ldots \}$

by

$\iota : \mathcal {D}\to \{2,3,\ldots \}$

by

The function

![]() $\iota $

defines a linear order on

$\iota $

defines a linear order on

![]() $\mathcal {D}$

. We recall the definition of the Haar system

$\mathcal {D}$

. We recall the definition of the Haar system

![]() $(h_I)_{I\in \mathcal {D}}$

. For

$(h_I)_{I\in \mathcal {D}}$

. For

![]() $I = [(i-1)/2^j,i/2^j)\in \mathcal {D}$

, we define

$I = [(i-1)/2^j,i/2^j)\in \mathcal {D}$

, we define

![]() $I^+, I^-\in \mathcal {D}$

as follows:

$I^+, I^-\in \mathcal {D}$

as follows:

![]() $I^+ = [(i-1)/2^j,(2i-1)/2^{j+1})$

,

$I^+ = [(i-1)/2^j,(2i-1)/2^{j+1})$

,

![]() $I^- = [(2i-1)/2^{j+1},i/2^j)$

, and

$I^- = [(2i-1)/2^{j+1},i/2^j)$

, and

We additionally define

![]() $h_\emptyset = \chi _{[0,1)}$

and

$h_\emptyset = \chi _{[0,1)}$

and

![]() $\mathcal {D}^+ = \mathcal {D}\cup \{\emptyset \}$

. We also define

$\mathcal {D}^+ = \mathcal {D}\cup \{\emptyset \}$

. We also define

![]() $\iota (\emptyset ) = 1$

. Then

$\iota (\emptyset ) = 1$

. Then

![]() $(h_I)_{I\in \mathcal {D}^+}$

is a monotone Schauder basis of

$(h_I)_{I\in \mathcal {D}^+}$

is a monotone Schauder basis of

![]() $L_1$

, with the linear order induced by

$L_1$

, with the linear order induced by

![]() $\iota $

. Henceforth, whenever we write

$\iota $

. Henceforth, whenever we write

![]() $\sum _{I\in \mathcal {D}^+}$

, we will always mean the sum is taken with this linear order

$\sum _{I\in \mathcal {D}^+}$

, we will always mean the sum is taken with this linear order

![]() $\iota $

.

$\iota $

.

For each

![]() $n\in \mathbb {N}\cup \{0\}$

, we define

$n\in \mathbb {N}\cup \{0\}$

, we define

An important realisation that will be used multiple times in the sequel is the following. Let

![]() $I\in \mathcal {D}$

. Then there exist a unique

$I\in \mathcal {D}$

. Then there exist a unique

![]() $k_0 \in \mathbb {N}$

and a unique decreasing sequence of intervals

$k_0 \in \mathbb {N}$

and a unique decreasing sequence of intervals

![]() $(I_k)_{k=0}^{k_0}$

in

$(I_k)_{k=0}^{k_0}$

in

![]() $(\mathcal {D}^+)$

so that

$(\mathcal {D}^+)$

so that

![]() $I_0 = \emptyset $

,

$I_0 = \emptyset $

,

![]() $I_1 = [0,1)$

and

$I_1 = [0,1)$

and

![]() $I_{k_0}=I$

; and for

$I_{k_0}=I$

; and for

![]() $k=1,2, \ldots , k_{0-1}$

,

$k=1,2, \ldots , k_{0-1}$

,

![]() $I_{k+1}=I^+_k$

or

$I_{k+1}=I^+_k$

or

![]() $I_{k+1}=I^-_k$

. In other words,

$I_{k+1}=I^-_k$

. In other words,

![]() $(I_k)_{k=1}^{k_0}$

consists of all elements of

$(I_k)_{k=1}^{k_0}$

consists of all elements of

![]() $\mathcal D^+$

that contain I, decreasingly ordered. For

$\mathcal D^+$

that contain I, decreasingly ordered. For

![]() $k=1,2, \ldots , k_0-1$

, put

$k=1,2, \ldots , k_0-1$

, put

![]() $\theta _k = 1$

, if

$\theta _k = 1$

, if

![]() $I_{k+1} = I_k^+$

and

$I_{k+1} = I_k^+$

and

![]() $\theta _k = -1$

if

$\theta _k = -1$

if

![]() $I_{k+1} = I_k^-$

. We then have the following formula, already discovered by Haar:

$I_{k+1} = I_k^-$

. We then have the following formula, already discovered by Haar:

$$ \begin{align} |I|^{-1}\chi_I = |I_{k_0}|^{-1}\chi_{I_{k_0}} = h_{I_0} + \sum_{k=1}^{k_0-1}\theta_k|I_k|^{-1}h_{I_k}. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} |I|^{-1}\chi_I = |I_{k_0}|^{-1}\chi_{I_{k_0}} = h_{I_0} + \sum_{k=1}^{k_0-1}\theta_k|I_k|^{-1}h_{I_k}. \end{align} $$

Note that in the above representation, if we define

![]() $I_{k_0} = I$

, then

$I_{k_0} = I$

, then

![]() $I_k = I_{k-1}^-$

or

$I_k = I_{k-1}^-$

or

![]() $I_k = I_{k-1}^+$

for

$I_k = I_{k-1}^+$

for

![]() $k=2,\ldots ,k_0$

. To simplify notation, we will henceforth make the convention

$k=2,\ldots ,k_0$

. To simplify notation, we will henceforth make the convention

![]() $\theta _0 = 1$

and

$\theta _0 = 1$

and

![]() $|I_0|^{-1} = |\emptyset |^{-1} = 1$

to be able to write

$|I_0|^{-1} = |\emptyset |^{-1} = 1$

to be able to write

$$ \begin{align} |I_{k_0}|^{-1}\chi_{I_{k_0}} = \sum_{k=0}^{k_0-1}\theta_k|I_k|^{-1}h_{I_k}. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} |I_{k_0}|^{-1}\chi_{I_{k_0}} = \sum_{k=0}^{k_0-1}\theta_k|I_k|^{-1}h_{I_k}. \end{align} $$

This representation will be used multiple times in this paper.

A relevant definition is that of

![]() $[\mathcal {D}^+]$

, the collection of all sequences

$[\mathcal {D}^+]$

, the collection of all sequences

![]() $(I_k)_{k=0}^\infty $

in

$(I_k)_{k=0}^\infty $

in

![]() $\mathcal {D}^+$

so that

$\mathcal {D}^+$

so that

![]() $I_0 = \emptyset $

,

$I_0 = \emptyset $

,

![]() $I_1 = [0,1)$

, and for each

$I_1 = [0,1)$

, and for each

![]() $k\in \mathbb {N}$

,

$k\in \mathbb {N}$

,

![]() $I_{k+1} = I_k^+$

or

$I_{k+1} = I_k^+$

or

![]() $I_{k+1} = I_k^-$

. Note that for

$I_{k+1} = I_k^-$

. Note that for

![]() $(I_k)_{k=0}^\infty \in [\mathcal {D}^+]$

and

$(I_k)_{k=0}^\infty \in [\mathcal {D}^+]$

and

![]() $k\in \mathbb {N}$

,

$k\in \mathbb {N}$

,

![]() $I_k\in \mathcal {D}_{k-1}$

. Each

$I_k\in \mathcal {D}_{k-1}$

. Each

![]() $(I_k)_{k=0}^\infty $

defines a sequence

$(I_k)_{k=0}^\infty $

defines a sequence

![]() $(\theta _k)_{k=1}^\infty $

as described in the paragraph above. This yields a bijection between

$(\theta _k)_{k=1}^\infty $

as described in the paragraph above. This yields a bijection between

![]() $[\mathcal {D}^+]$

and

$[\mathcal {D}^+]$

and

![]() $\{-1,1\}^{\mathbb {N}}$

. This fact will be used more than once. On

$\{-1,1\}^{\mathbb {N}}$

. This fact will be used more than once. On

![]() $\{-1,1\}^{\mathbb {N}}$

, we will consider the product of the uniform distribution on

$\{-1,1\}^{\mathbb {N}}$

, we will consider the product of the uniform distribution on

![]() $\{-1,1\}$

, which via this bijection generates a probability on

$\{-1,1\}$

, which via this bijection generates a probability on

![]() $[\mathcal {D}^+]$

, which we will also denote by

$[\mathcal {D}^+]$

, which we will also denote by

![]() $|\cdot |$

. Also, we consider on

$|\cdot |$

. Also, we consider on

![]() $[\mathcal D^+] $

the image topology of the product of the discrete topology on

$[\mathcal D^+] $

the image topology of the product of the discrete topology on

![]() $\{-1,1\}$

via that bijection.

$\{-1,1\}$

via that bijection.

2.3 Haar multipliers on

$L_1$

$L_1$

A Haar multiplier is a linear map D, defined on the linear span of the Haar system, for which every Haar vector

![]() $h_I$

is an eigenvector with eigenvalue

$h_I$

is an eigenvector with eigenvalue

![]() $a_I$

. We denote the space of bounded Haar multipliers

$a_I$

. We denote the space of bounded Haar multipliers

![]() $D:L_1\to L_1$

by

$D:L_1\to L_1$

by

![]() $\mathcal {L}_{HM}(L_1)$

. In this subsection, we recall a formula for the norm of a Haar multiplier that was observed by Semenov and Uksusov in [Reference Semenov and Uksusov34, Reference Semenov and Uksusov35]. We then use Haar multipliers to sketch a proof of the fact that every bounded linear operator on

$\mathcal {L}_{HM}(L_1)$

. In this subsection, we recall a formula for the norm of a Haar multiplier that was observed by Semenov and Uksusov in [Reference Semenov and Uksusov34, Reference Semenov and Uksusov35]. We then use Haar multipliers to sketch a proof of the fact that every bounded linear operator on

![]() $L_1$

is an approximate 1-projectional factor of a scalar operator.

$L_1$

is an approximate 1-projectional factor of a scalar operator.

This recent formula of Semenov and Uksusov is a very elegant characterisation of boundedness on Haar multipliers on

![]() $L_1$

. In that spirit, Girardi studied related operators on

$L_1$

. In that spirit, Girardi studied related operators on

![]() $L_p$

and

$L_p$

and

![]() $L_p(X)$

of a multiplier type [Reference Girardi17]. Wark has since simplified the proof of Semenov-Uksusov [Reference Wark38] as well as extended the formula to the vector-valued case [Reference Wark39, Reference Wark40].

$L_p(X)$

of a multiplier type [Reference Girardi17]. Wark has since simplified the proof of Semenov-Uksusov [Reference Wark38] as well as extended the formula to the vector-valued case [Reference Wark39, Reference Wark40].

Proposition 2.5. Let

![]() $(I_k)_{k=0}^\infty \in [\mathcal {D}^+]$

be associated to

$(I_k)_{k=0}^\infty \in [\mathcal {D}^+]$

be associated to

![]() $(\theta _k)_{k=1}^\infty \in \{-1,1\}^{\mathbb {N}}$

. For

$(\theta _k)_{k=1}^\infty \in \{-1,1\}^{\mathbb {N}}$

. For

![]() $k\in \mathbb {N}$

define

$k\in \mathbb {N}$

define

![]() $B_k = I_k\setminus I_{k+1}$

, and let

$B_k = I_k\setminus I_{k+1}$

, and let

![]() $(a_k)_{k=0}^n$

be a sequence of scalars.

$(a_k)_{k=0}^n$

be a sequence of scalars.

Then we have

$$ \begin{align} \frac{1}{3}\Big(\sum_{k=1}^n|a_k - a_{k-1}| + |a_n|\Big) \leq \left\|\sum_{k=0}^na_k\theta_k|I_k|^{-1} h_{I_k}\right\|_{L_1} \leq \sum_{k=1}^n|a_k - a_{k-1}| + |a_n|, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{1}{3}\Big(\sum_{k=1}^n|a_k - a_{k-1}| + |a_n|\Big) \leq \left\|\sum_{k=0}^na_k\theta_k|I_k|^{-1} h_{I_k}\right\|_{L_1} \leq \sum_{k=1}^n|a_k - a_{k-1}| + |a_n|, \end{align} $$

and for any

![]() $1\le m< n$

,

$1\le m< n$

,

$$ \begin{align} & \left\|\Big(\sum_{k=0}^na_k\theta_k|I_k|^{-1} h_{I_k}\Big)\big|_{\bigcup_{j=m}^n B_j}\right\|_{L_1}\ge \frac{1}{3}\Big(\sum_{k=m+1}^n|a_k - a_{k-1}|+|a_n|\Big). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} & \left\|\Big(\sum_{k=0}^na_k\theta_k|I_k|^{-1} h_{I_k}\Big)\big|_{\bigcup_{j=m}^n B_j}\right\|_{L_1}\ge \frac{1}{3}\Big(\sum_{k=m+1}^n|a_k - a_{k-1}|+|a_n|\Big). \end{align} $$

Proof. Note that the sequence

![]() $(B_k)_{k=1}^\infty $

is a partition of

$(B_k)_{k=1}^\infty $

is a partition of

![]() $[0,1)$

, and for

$[0,1)$

, and for

![]() $k\in \mathbb {N}$

,

$k\in \mathbb {N}$

,

![]() $B_k$

is the set in

$B_k$

is the set in

![]() $[0,1]$

of measure

$[0,1]$

of measure

![]() $2^{-k}$

on which

$2^{-k}$

on which

![]() $\theta _k h_{I_k}$

takes the value

$\theta _k h_{I_k}$

takes the value

![]() $-1$

. Let

$-1$

. Let

![]() $f = a_0 h_\emptyset + \sum _{k=1}^n \theta _ka_k|I_k|^{-1}h_{I_k}$

. For

$f = a_0 h_\emptyset + \sum _{k=1}^n \theta _ka_k|I_k|^{-1}h_{I_k}$

. For

![]() $k\in \mathbb {N}$

, put

$k\in \mathbb {N}$

, put

![]() $b_k = a_k$

if

$b_k = a_k$

if

![]() $k\leq n$

and

$k\leq n$

and

![]() $b_k = 0$

otherwise. For each

$b_k = 0$

otherwise. For each

![]() $k\in \mathbb {N}$

, the function f is constant on

$k\in \mathbb {N}$

, the function f is constant on

![]() $B_k$

and in fact for

$B_k$

and in fact for

![]() $s\in B_k$

, we have

$s\in B_k$

, we have

$$ \begin{align*} f(s) =b_0 + \sum_{j=1}^{k-1}|I_j|^{-1}b_j - |I_k|^{-1}b_k = b_0 + \sum_{j=1}^{k-1}2^{j-1}b_j - 2^{k-1}b_k =: c_k. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} f(s) =b_0 + \sum_{j=1}^{k-1}|I_j|^{-1}b_j - |I_k|^{-1}b_k = b_0 + \sum_{j=1}^{k-1}2^{j-1}b_j - 2^{k-1}b_k =: c_k. \end{align*} $$

Therefore, for any

![]() $m=1,2,\ldots n$

,

$m=1,2,\ldots n$

,

$$ \begin{align} \left\|f \chi_{\bigcup_{j=m}^n B_j} \right\|_{L_1} = \sum_{k=m}^\infty |X_k|, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \left\|f \chi_{\bigcup_{j=m}^n B_j} \right\|_{L_1} = \sum_{k=m}^\infty |X_k|, \end{align} $$

where for each

![]() $k\in \mathbb {N}$

,

$k\in \mathbb {N}$

,

$$\begin{align*}X_k = \frac{c_k}{2^{k}} = \frac{1}{2^{k}}b_{0} + \sum_{j=1}^{k-1}\frac{2^{j-1}}{2^{k}}b_j - \frac{1}{2}b_k.\end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}X_k = \frac{c_k}{2^{k}} = \frac{1}{2^{k}}b_{0} + \sum_{j=1}^{k-1}\frac{2^{j-1}}{2^{k}}b_j - \frac{1}{2}b_k.\end{align*}$$

Putting

![]() $X_0 = 0$

, a calculation yields that for all

$X_0 = 0$

, a calculation yields that for all

![]() $k\in \mathbb {N}$

,

$k\in \mathbb {N}$

,

Applying the triangle inequality to equations (23) and (24), we conclude

$$ \begin{align*} \| f\|_{L_1}&=\sum_{k=m}^\infty |X_k|=\sum_{k=1}^\infty 2|X_k|-|X_{k-1}|\\ &\le \sum_{k=1}^\infty |2X_k -X_{k-1}|=\sum_{k=1}^\infty|b_k-b_{k-1}|, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \| f\|_{L_1}&=\sum_{k=m}^\infty |X_k|=\sum_{k=1}^\infty 2|X_k|-|X_{k-1}|\\ &\le \sum_{k=1}^\infty |2X_k -X_{k-1}|=\sum_{k=1}^\infty|b_k-b_{k-1}|, \end{align*} $$

which yields the upper bound of equation (21). The lower bound is proved with a similar computation. To obtain equation (22), we deduce from equation (24)

$$ \begin{align*} &\sum_{k=m+1}^\infty |X_k| \ge\frac12 \sum_{k=m+1}^\infty |b_k-b_{k-1}|-\frac12\sum_{k=m} |X_k| \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} &\sum_{k=m+1}^\infty |X_k| \ge\frac12 \sum_{k=m+1}^\infty |b_k-b_{k-1}|-\frac12\sum_{k=m} |X_k| \end{align*} $$

and therefore

$$ \begin{align*} & \frac32 \sum_{k=m+1}^\infty |X_k| +\frac12 |X_{m}| \ge \frac12 \sum_{k=m+1}^\infty |b_k-b_{k-1}|, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} & \frac32 \sum_{k=m+1}^\infty |X_k| +\frac12 |X_{m}| \ge \frac12 \sum_{k=m+1}^\infty |b_k-b_{k-1}|, \end{align*} $$

which yields

$$ \begin{align*} & \| f \chi_{\bigcup_{j=m}^n B_j}\|_{L_1} = \sum_{k=m}^\infty |X_k| \ge \sum_{k=m+1}^\infty |X_k| +\frac13|X_m| \ge \frac13 \sum_{k=m+1}^\infty |b_k-b_{k-1}| \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} & \| f \chi_{\bigcup_{j=m}^n B_j}\|_{L_1} = \sum_{k=m}^\infty |X_k| \ge \sum_{k=m+1}^\infty |X_k| +\frac13|X_m| \ge \frac13 \sum_{k=m+1}^\infty |b_k-b_{k-1}| \end{align*} $$

and proves equation (22).

Theorem 2.6 Semenov-Uksusov, [Reference Semenov and Uksusov34, Reference Semenov and Uksusov35]

Let

![]() $(a_I)_{I\in \mathcal {D}^+}$

be a collection of scalars and D be the associated Haar multiplier. Define

$(a_I)_{I\in \mathcal {D}^+}$

be a collection of scalars and D be the associated Haar multiplier. Define

$$ \begin{align} {\left\vert\kern-0.25ex\left\vert\kern-0.25ex\left\vert D \right\vert\kern-0.25ex\right\vert\kern-0.25ex\right\vert} = \sup\Big(\sum_{k=1}^\infty\big |a_{I_k} - a_{I_{k-1}}\big|+\lim_k\big|a_{I_k}\big|\Big), \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} {\left\vert\kern-0.25ex\left\vert\kern-0.25ex\left\vert D \right\vert\kern-0.25ex\right\vert\kern-0.25ex\right\vert} = \sup\Big(\sum_{k=1}^\infty\big |a_{I_k} - a_{I_{k-1}}\big|+\lim_k\big|a_{I_k}\big|\Big), \end{align} $$

where the supremum is taken over all

![]() $(I_k)_{k=0}^\infty \in [\mathcal {D}^+]$

. Then D is bounded (and thus extends to a bounded linear operator on

$(I_k)_{k=0}^\infty \in [\mathcal {D}^+]$

. Then D is bounded (and thus extends to a bounded linear operator on

![]() $L_1(X)$

) if and only if

$L_1(X)$

) if and only if

![]() ${\left \vert \kern -0.25ex\left \vert \kern -0.25ex\left \vert D \right \vert \kern -0.25ex\right \vert \kern -0.25ex\right \vert }<\infty $

. More precisely,

${\left \vert \kern -0.25ex\left \vert \kern -0.25ex\left \vert D \right \vert \kern -0.25ex\right \vert \kern -0.25ex\right \vert }<\infty $

. More precisely,

Proof. By equation (19), D is always well defined on the linear span of the set

![]() $\mathcal {X} = \{|I|^{-1}\chi _I:I\in \mathcal {D}\}$

. In fact, the closed convex symmetric hull of

$\mathcal {X} = \{|I|^{-1}\chi _I:I\in \mathcal {D}\}$

. In fact, the closed convex symmetric hull of

![]() $\mathcal {X}$

is the unit ball of

$\mathcal {X}$

is the unit ball of

![]() $L_1$

. We deduce that

$L_1$

. We deduce that

![]() $\|D\| = \sup \{\|Df\|:f\in \mathcal {X}\}$

, under the convention that

$\|D\| = \sup \{\|Df\|:f\in \mathcal {X}\}$

, under the convention that

![]() $\|D\| = \infty $

if and only if D is unbounded. Fix

$\|D\| = \infty $

if and only if D is unbounded. Fix

![]() $f = |I|^{-1}\chi _I\in \mathcal {X}$

. Use equation (19) to write

$f = |I|^{-1}\chi _I\in \mathcal {X}$

. Use equation (19) to write

$$\begin{align*}f = |I_{k_0}|^{-1}\chi_{I_{k_0}} = \sum_{k=0}^{k_0-1}\theta_k|I_k|^{-1}h_{I_k},\ that is,\ Df = \sum_{k=0}^{k_0-1}a_k\theta_k|I_k|^{-1}h_{I_k}.\end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}f = |I_{k_0}|^{-1}\chi_{I_{k_0}} = \sum_{k=0}^{k_0-1}\theta_k|I_k|^{-1}h_{I_k},\ that is,\ Df = \sum_{k=0}^{k_0-1}a_k\theta_k|I_k|^{-1}h_{I_k}.\end{align*}$$

Extend

![]() $(I_k)_{k=0}^{k_0}$

to a branch

$(I_k)_{k=0}^{k_0}$

to a branch

![]() $(I_k)_{k=0}^\infty $

. By equation (21), we have

$(I_k)_{k=0}^\infty $

. By equation (21), we have

$$ \begin{align} \frac{1}{3}\big(\sum_{k=1}^{k_0-1}|a_{I_k} - a_{I_{k-1}}| + |a_{I_{k_0-1}}|\big) \leq \|Df\|_{L_1} \leq \sum_{k=1}^{k_0-1}|a_{I_k} - a_{I_{k-1}}| + |a_{I_{k_0-1}}|. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{1}{3}\big(\sum_{k=1}^{k_0-1}|a_{I_k} - a_{I_{k-1}}| + |a_{I_{k_0-1}}|\big) \leq \|Df\|_{L_1} \leq \sum_{k=1}^{k_0-1}|a_{I_k} - a_{I_{k-1}}| + |a_{I_{k_0-1}}|. \end{align} $$

By the triangle inequality,

![]() $\|Df\|_{L_1} \leq \sum _{k=1}^{\infty }|a_{I_k} - a_{I_{k-1}}| + \lim _k|a_{I_{k}}| \leq {\left \vert \kern -0.25ex\left \vert \kern -0.25ex\left \vert D \right \vert \kern -0.25ex\right \vert \kern -0.25ex\right \vert }$

. The lower bound is achieved by taking in equation (27) all

$\|Df\|_{L_1} \leq \sum _{k=1}^{\infty }|a_{I_k} - a_{I_{k-1}}| + \lim _k|a_{I_{k}}| \leq {\left \vert \kern -0.25ex\left \vert \kern -0.25ex\left \vert D \right \vert \kern -0.25ex\right \vert \kern -0.25ex\right \vert }$

. The lower bound is achieved by taking in equation (27) all

![]() $f\in \mathcal {X}$

.

$f\in \mathcal {X}$

.

The following special type of Haar multiplier will appear in the sequel.

Example 2.7. Let

![]() $\mathscr {A}\subset [\mathcal {D}^+]$

be a nonempty set, and define the set

$\mathscr {A}\subset [\mathcal {D}^+]$

be a nonempty set, and define the set

![]() $\mathcal {A} = \cup _{k_0=0}^\infty \{I_{k_0}:(I_k)_{k=0}^\infty \in \mathscr {A}\}\subset \mathcal {D}^+$

. Let

$\mathcal {A} = \cup _{k_0=0}^\infty \{I_{k_0}:(I_k)_{k=0}^\infty \in \mathscr {A}\}\subset \mathcal {D}^+$

. Let

![]() $P_{\mathscr {A}}$

denote the Haar multiplier that has entries

$P_{\mathscr {A}}$

denote the Haar multiplier that has entries

![]() $a_I = 1$

for

$a_I = 1$

for

![]() $I\in \mathcal {A}$

and

$I\in \mathcal {A}$

and

![]() $a_I = 0$

otherwise. Then by Theorem 2.6,

$a_I = 0$

otherwise. Then by Theorem 2.6,

![]() $\|P_{\mathscr {A}}\|\leq {\left \vert \kern -0.25ex\left \vert \kern -0.25ex\left \vert P_{\mathscr {A}} \right \vert \kern -0.25ex\right \vert \kern -0.25ex\right \vert } = 1$

, and therefore

$\|P_{\mathscr {A}}\|\leq {\left \vert \kern -0.25ex\left \vert \kern -0.25ex\left \vert P_{\mathscr {A}} \right \vert \kern -0.25ex\right \vert \kern -0.25ex\right \vert } = 1$

, and therefore

![]() $P_{\mathscr {A}}$

defines a norm-one projection onto

$P_{\mathscr {A}}$

defines a norm-one projection onto

![]() $Y_{\mathscr {A}} = \overline {\langle \{h_I:I\in \mathcal {A}\}\rangle }$

.

$Y_{\mathscr {A}} = \overline {\langle \{h_I:I\in \mathcal {A}\}\rangle }$

.

The following elementary remark will be useful eventually.

Remark 2.8. Let

![]() $\mathscr {A}$

be a nonempty closed subset of

$\mathscr {A}$

be a nonempty closed subset of

![]() $[\mathcal {D}^+]$

and

$[\mathcal {D}^+]$

and

![]() $\mathcal {A} = \cup _{k_0=0}^\infty \{I_{k_0}:(I_k)_{k=0}^\infty \in \mathscr {A}\}$

. Let D be a Haar multiplier with entries that are zero outside

$\mathcal {A} = \cup _{k_0=0}^\infty \{I_{k_0}:(I_k)_{k=0}^\infty \in \mathscr {A}\}$

. Let D be a Haar multiplier with entries that are zero outside

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

. Then

$\mathcal {A}$

. Then

$$\begin{align*}{\left\vert\kern-0.25ex\left\vert\kern-0.25ex\left\vert D \right\vert\kern-0.25ex\right\vert\kern-0.25ex\right\vert} = \sup_{(I_k)_{k=0}^\infty\in\mathscr{A}}(\sum_{k=1}^\infty|a_{I_k}-a_{k-1}| + \lim_k|a_{I_k}|).\end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}{\left\vert\kern-0.25ex\left\vert\kern-0.25ex\left\vert D \right\vert\kern-0.25ex\right\vert\kern-0.25ex\right\vert} = \sup_{(I_k)_{k=0}^\infty\in\mathscr{A}}(\sum_{k=1}^\infty|a_{I_k}-a_{k-1}| + \lim_k|a_{I_k}|).\end{align*}$$

Haar multipliers provide a short path to a proof of the fact that every operator on

![]() $L_1$

is an approximate 1-projectional factor of a scalar operator, which in turn yields Enflo’s theorem [Reference Maurey26] that

$L_1$

is an approximate 1-projectional factor of a scalar operator, which in turn yields Enflo’s theorem [Reference Maurey26] that

![]() $L_1$

is primary.

$L_1$

is primary.

Theorem 2.9. The following are true in the space

![]() $L_1$

.

$L_1$

.

-

(i) Let

$D:L_1\to L_1$

be a bounded Haar multiplier. For every

$D:L_1\to L_1$

be a bounded Haar multiplier. For every

$\varepsilon>0$

, D is a 1-projectional factor with error

$\varepsilon>0$

, D is a 1-projectional factor with error

$\varepsilon $

of a scalar operator.

$\varepsilon $

of a scalar operator. -

(ii) Let

$T:L_1\to L_1$

be a bounded linear operator. For every

$T:L_1\to L_1$

be a bounded linear operator. For every

$\varepsilon>0$

, T is a 1-projectional factor with error

$\varepsilon>0$

, T is a 1-projectional factor with error

$\varepsilon $

of a bounded Haar multiplier

$\varepsilon $

of a bounded Haar multiplier

$D:L_1\to L_1$

.

$D:L_1\to L_1$

.

In particular, for every

![]() $\varepsilon>0$

, every bounded linear operator

$\varepsilon>0$

, every bounded linear operator

![]() $T:L_1\to L_1$

is a 1-projectional factor with error

$T:L_1\to L_1$

is a 1-projectional factor with error

![]() $\varepsilon $

of a scalar operator.

$\varepsilon $

of a scalar operator.

We wish to provide a sketch of the proof of the above. First, we will use it at the end of the paper; and second, it provides an introduction to the basis of the methods used in the paper. Now, and numerous times in the sequel, we require the following notation and definition.

Notation. For every disjoint collection

![]() $\Delta $

of

$\Delta $

of

![]() $\mathcal {D}^+$

and

$\mathcal {D}^+$

and

![]() $\theta \in \{-1,1\}^\Delta $

, we denote

$\theta \in \{-1,1\}^\Delta $

, we denote

![]() $h_\Delta ^\theta = \sum _{J\in \Delta }\theta _Jh_J$

. If

$h_\Delta ^\theta = \sum _{J\in \Delta }\theta _Jh_J$

. If

![]() $\theta _J = 1$

for all

$\theta _J = 1$

for all

![]() $J\in \Delta $

, we write

$J\in \Delta $

, we write

![]() $h_\Delta = \sum _{j\in \Delta }h_J$

. For a finite disjoint collection

$h_\Delta = \sum _{j\in \Delta }h_J$

. For a finite disjoint collection

![]() $\Delta $

of

$\Delta $

of

![]() $\mathcal {D}$

, we denote

$\mathcal {D}$

, we denote

![]() $\Delta ^* = \cup \{I:I\in \Delta \}$

.

$\Delta ^* = \cup \{I:I\in \Delta \}$

.

Definition 2.10. A faithful Haar system is a collection

![]() $(\tilde h_I)_{I\in \mathcal {D}^+}$

so that for each

$(\tilde h_I)_{I\in \mathcal {D}^+}$

so that for each

![]() $I\in \mathcal {D}^+$

, the function

$I\in \mathcal {D}^+$

, the function

![]() $\tilde h_I$

is of the form

$\tilde h_I$

is of the form

![]() $\tilde h_I = h_{\Delta _I}^{\theta _I}$

, for some finite disjoint collection

$\tilde h_I = h_{\Delta _I}^{\theta _I}$

, for some finite disjoint collection

![]() $\Delta _I$

of

$\Delta _I$

of

![]() $\mathcal {D}$

, and so that

$\mathcal {D}$

, and so that

-

(i)

$\Delta _\emptyset ^* = \Delta _{[0,1)}^* = [0,1)$

, and for each

$\Delta _\emptyset ^* = \Delta _{[0,1)}^* = [0,1)$

, and for each

$I\in \mathcal {D}$

, we have

$I\in \mathcal {D}$

, we have

$|\Delta _I| = |I|$

,

$|\Delta _I| = |I|$

, -

(ii) for every

$I\in \mathcal {D}$

, we have that

$I\in \mathcal {D}$

, we have that

$\Delta _{I^+}^* = [\tilde h_\emptyset \tilde h_I = 1]$

and

$\Delta _{I^+}^* = [\tilde h_\emptyset \tilde h_I = 1]$

and

$\Delta _{I^-}^* = [\tilde h_\emptyset \tilde h_I = -1]$

.

$\Delta _{I^-}^* = [\tilde h_\emptyset \tilde h_I = -1]$

.

Remark 2.11. It is immediate that

![]() $(\tilde h_\emptyset \tilde h_I)_{I\in \mathcal {D}^+}$

is distributionally equivalent to

$(\tilde h_\emptyset \tilde h_I)_{I\in \mathcal {D}^+}$

is distributionally equivalent to

![]() $(h_I)_{I\in \mathcal {D}^+}$

. Therefore,

$(h_I)_{I\in \mathcal {D}^+}$

. Therefore,

![]() $(\tilde h_I)_{I\in \mathcal {D}^+}$

is isometrically equivalent to

$(\tilde h_I)_{I\in \mathcal {D}^+}$

is isometrically equivalent to

![]() $(h_I)_{I\in \mathcal {D}^+}$

, both in

$(h_I)_{I\in \mathcal {D}^+}$

, both in

![]() $L_1$

and in

$L_1$

and in

![]() $L_\infty $

. In particular,

$L_\infty $

. In particular,

defines a norm-one projection onto a subspace Z of

![]() $L_1$

that is isometrically isomorphic to

$L_1$

that is isometrically isomorphic to

![]() $L_1$

. Note that unless

$L_1$

. Note that unless

![]() $h_\emptyset = 1$

, P is not a conditional expectation as

$h_\emptyset = 1$

, P is not a conditional expectation as

![]() $P\chi _{[0,1)} = 0$

. Instead, it is of the form

$P\chi _{[0,1)} = 0$

. Instead, it is of the form

![]() $Pf = \tilde h_\emptyset E(\tilde h_\emptyset f|\Sigma )$

, where

$Pf = \tilde h_\emptyset E(\tilde h_\emptyset f|\Sigma )$

, where

![]() $\Sigma = \sigma (\tilde h_\emptyset \tilde h_I)_{I\in \mathcal {D}^+}$

. Since

$\Sigma = \sigma (\tilde h_\emptyset \tilde h_I)_{I\in \mathcal {D}^+}$

. Since

![]() $\tilde h_\emptyset $

is not

$\tilde h_\emptyset $

is not

![]() $\Sigma $

-measurable, it cannot be eliminated. The advantage of the notion of a faithful Haar system is that one can be constructed in every tail of the Haar system. The drawback is that it causes a slight notational burden when having to adjust for the initial function

$\Sigma $

-measurable, it cannot be eliminated. The advantage of the notion of a faithful Haar system is that one can be constructed in every tail of the Haar system. The drawback is that it causes a slight notational burden when having to adjust for the initial function

![]() $\tilde h_\emptyset $

in several situations.

$\tilde h_\emptyset $

in several situations.

We will several times recursively construct faithful Haar systems

![]() $(\tilde h_I)_{I\in \mathcal {D}^+}$

, which means we first choose

$(\tilde h_I)_{I\in \mathcal {D}^+}$

, which means we first choose

![]() $\tilde h_\emptyset $

, second

$\tilde h_\emptyset $

, second

![]() $\tilde h_{[0,1)}$

and then

$\tilde h_{[0,1)}$

and then

![]() $\tilde h_I$

,

$\tilde h_I$

,

![]() $I\in \mathcal D$

, assuming that

$I\in \mathcal D$

, assuming that

![]() $\tilde h_J$

was chosen for all

$\tilde h_J$

was chosen for all

![]() $J\in \mathcal D ^+$

with

$J\in \mathcal D ^+$

with

![]() $\iota (J) < \iota (I)$

.

$\iota (J) < \iota (I)$

.

Proof of Theorem 2.9

Let us sketch the proof of the first statement. Let

![]() $(a_I)_{I\in \mathcal {D}^+}$

be the entries of D. For every

$(a_I)_{I\in \mathcal {D}^+}$

be the entries of D. For every

![]() $I\in \mathcal {D}$

, denote by

$I\in \mathcal {D}$

, denote by

![]() $Q_I$

the Haar multiplier that has entries 1 for all

$Q_I$

the Haar multiplier that has entries 1 for all

![]() $J\subset I$

and zero for all others. Then

$J\subset I$

and zero for all others. Then

![]() ${\left \vert \kern -0.25ex\left \vert \kern -0.25ex\left \vert Q_I \right \vert \kern -0.25ex\right \vert \kern -0.25ex\right \vert } = 1$

. First, note that for every

${\left \vert \kern -0.25ex\left \vert \kern -0.25ex\left \vert Q_I \right \vert \kern -0.25ex\right \vert \kern -0.25ex\right \vert } = 1$

. First, note that for every

![]() $\varepsilon>0$

, there exists

$\varepsilon>0$

, there exists

![]() $I_0\in \mathcal {D}^+$

so that

$I_0\in \mathcal {D}^+$

so that

![]() ${\left \vert \kern -0.25ex\left \vert \kern -0.25ex\left \vert DQ_{I_0} - a_{I_0}Q_{I_0} \right \vert \kern -0.25ex\right \vert \kern -0.25ex\right \vert }\leq \varepsilon $

. Otherwise, we could easily deduce

${\left \vert \kern -0.25ex\left \vert \kern -0.25ex\left \vert DQ_{I_0} - a_{I_0}Q_{I_0} \right \vert \kern -0.25ex\right \vert \kern -0.25ex\right \vert }\leq \varepsilon $

. Otherwise, we could easily deduce

![]() ${\left \vert \kern -0.25ex\left \vert \kern -0.25ex\left \vert D \right \vert \kern -0.25ex\right \vert \kern -0.25ex\right \vert } = \infty $

. Construct a dilated and renormalised faithful Haar system

${\left \vert \kern -0.25ex\left \vert \kern -0.25ex\left \vert D \right \vert \kern -0.25ex\right \vert \kern -0.25ex\right \vert } = \infty $

. Construct a dilated and renormalised faithful Haar system

![]() $(\tilde h_I)_{I\in \mathcal {D}^+}$

with closed linear span Z in the range of

$(\tilde h_I)_{I\in \mathcal {D}^+}$

with closed linear span Z in the range of

![]() $Q_{I_0}$

, and let

$Q_{I_0}$

, and let

![]() $P:L_1\to Z$

be the corresponding norm-one projection and

$P:L_1\to Z$

be the corresponding norm-one projection and

![]() $A:L_1\to Z$

be an onto isometry. Then

$A:L_1\to Z$

be an onto isometry. Then

![]() $\|A^{-1}PDA - a_{I_0}I\| \leq \varepsilon $

.

$\|A^{-1}PDA - a_{I_0}I\| \leq \varepsilon $

.

For the second part, we will use that the Rademacher sequence

![]() $(r_n)_n$

(i.e.,

$(r_n)_n$

(i.e.,

![]() $r_n = \sum _{L\in \mathcal {D}_n}h_L$

, for

$r_n = \sum _{L\in \mathcal {D}_n}h_L$

, for

![]() $n\in \mathbb {N}$

)) is weakly null in

$n\in \mathbb {N}$

)) is weakly null in

![]() $L_1$

and

$L_1$

and

![]() $w^*$

-null in

$w^*$

-null in

![]() $(L_1)^* \equiv L_\infty $

. Using this fact, we inductively construct a faithful Haar system

$(L_1)^* \equiv L_\infty $

. Using this fact, we inductively construct a faithful Haar system

![]() $(\tilde h_I)_{I\in \mathcal {D}^+}$

so that for each

$(\tilde h_I)_{I\in \mathcal {D}^+}$

so that for each

![]() $I\neq J$

, we have

$I\neq J$

, we have

where

![]() $(\varepsilon _{(I,J)})_{(I,J)\in \mathcal {D}^+}$

is a prechosen collection of positive real numbers with

$(\varepsilon _{(I,J)})_{(I,J)\in \mathcal {D}^+}$

is a prechosen collection of positive real numbers with

![]() $\sum \varepsilon _{(I,J)} \leq \varepsilon $

. This is done as follows. If we have chosen

$\sum \varepsilon _{(I,J)} \leq \varepsilon $

. This is done as follows. If we have chosen

![]() $\tilde h_I$

for

$\tilde h_I$

for

![]() $\iota (I) = 1,\ldots ,k-1$

. Let

$\iota (I) = 1,\ldots ,k-1$

. Let

![]() $I\in \mathcal {D}^+$

with

$I\in \mathcal {D}^+$

with

![]() $\iota (I) = k$

, and let

$\iota (I) = k$

, and let

![]() $I_0$

be the predecessor of I: that is, either

$I_0$

be the predecessor of I: that is, either

![]() $I = I_0^+$

or

$I = I_0^+$

or

![]() $I = I_0^-$

. Let us assume

$I = I_0^-$

. Let us assume

![]() $I = I_0^+$

. We then choose the next function

$I = I_0^+$

. We then choose the next function

![]() $\tilde h_I$

among the terms of a Rademacher sequence with support

$\tilde h_I$

among the terms of a Rademacher sequence with support

![]() $[\tilde h_\emptyset \tilde h_{I_0} = 1]$

. Denote by Z the closed linear span of

$[\tilde h_\emptyset \tilde h_{I_0} = 1]$

. Denote by Z the closed linear span of

![]() $(\tilde h_I)_{I\in \mathcal {D}^+}$

, and take the canonical projection

$(\tilde h_I)_{I\in \mathcal {D}^+}$

, and take the canonical projection

![]() $P:L_1\to Z$

as well as the onto isometry

$P:L_1\to Z$

as well as the onto isometry

![]() $A:L_1\to Z$

given by

$A:L_1\to Z$

given by

![]() $A h_I = \tilde h_I$

. Consider the operator

$A h_I = \tilde h_I$

. Consider the operator

![]() $S=A^{-1}PTA:L_1\to L_1$

, and note that for all

$S=A^{-1}PTA:L_1\to L_1$

, and note that for all

![]() $I\neq J$

, we have

$I\neq J$

, we have

![]() $|\langle h_I, S(|J|^{-1}h_J) \rangle | = |\langle \tilde h_I, T(|J|^{-1}\tilde h_J )\rangle | \leq \varepsilon _{(I,J)}$

. It follows that the entries

$|\langle h_I, S(|J|^{-1}h_J) \rangle | = |\langle \tilde h_I, T(|J|^{-1}\tilde h_J )\rangle | \leq \varepsilon _{(I,J)}$

. It follows that the entries

![]() $a_I = \langle h_I, S(|I|^{-1}h_I )\rangle $

define a bounded Haar multiplier D and

$a_I = \langle h_I, S(|I|^{-1}h_I )\rangle $

define a bounded Haar multiplier D and

![]() $\|S - D\| \leq \varepsilon $

: that is, T is a 1-projectional factor with error

$\|S - D\| \leq \varepsilon $

: that is, T is a 1-projectional factor with error

![]() $\varepsilon $

of D.

$\varepsilon $

of D.

2.4 Haar system spaces

We define Haar system spaces. These are Banach spaces of scalar function generated by the Haar system in which two functions with the same distribution have the same norm. This abstraction does not impose any notational burden on the proof of the main result. The only difference to the case

![]() $X= L_p$