A. Introduction

It is out of question that nowadays the European competence to defend rule of law and human rightsFootnote 1 —hereafter jointly referred to as rule of law—against Member States became one of the core issues of the European project. In the last decade, EU institutions, in particular the European Commission and the European Parliament, have made several, benevolent, yet feeble, attempts to enforce rule of law requirements on some of the Member States.Footnote 2 All of these showcased how little power the EU has when encountering recalcitrant Member States who are contemptuous of the EU’s fundamental values.Footnote 3 While this facet of the EU’s human rights question has subsisted from the very outset, it was the controversies of the last decade that made it a central and non-evadable issue.Footnote 4

The effective protection of rule of law throughout the European Union became one of the central issues of the European project’s furtherance or even preservation. It is a historical question that may open the next phase in Europe’s arduous path to an “ever closer union.”Footnote 5 In this sense, very perversely, those Member State governments that are loudly and desperately defying the EU and its fundamental values may significantly contribute to the shifting of a further major competence to the “federal” level.Footnote 6 The European project’s history has shown us that challenges that do not kill the integration make it stronger.

This Article addresses the EU’s current constitutional predicament and proposes the adoption of a doctrine of incorporation à l’européenne. The problem and the proposed solution are presented in three steps.

First, the Article coins a new term, diagonality, which describes the EU’s rule-of-law problem and gives an account of the currently missing status of diagonality. This section proceeds to discuss: The “apparent diagonal application” of EU rule of law and its spill-over effects, the “Al Capone” tricks where the Commission used the rim—supportive by-effects—of unrelated EU law norms to protect rule of law in the Member States,Footnote 7 the ineffective security valve of Article 7 TEU, and the scholarly attempts to find a solution to the diagonality problem.

Second, the Article shows that the diagonal application is a typical problem of composite federal polities and comparative analysis may enlighten the further development of European constitutional law. This section gives an account of the patterns developed by other federal polities and argues that the approaches of loose federations where constituent entities have significant regulatory powers are, in this regard, instructive. Although the EU is not a state, it is not a traditional international organization either. The idiosyncratic nature of the EU legal order expresses the EU’s unique nature as a half-made federation.Footnote 8 The nature of the law, which features the doctrines of direct effect and supremacy, as well as the voluntary conferral of parts of national sovereignty, the circle of “common matters,” and the interdependence of Member States all have reached a quality where comparisons to federal states hold out meaningful results. Furthermore, while comparative federalism offers points of reference and provides an inventory of techniques and concepts, EU law will have to find a unique solution for its multilayered constitutional system equally featured by a set of common values and national constitutional identities.Footnote 9

Third, this Article advances a proposal for a European incorporation doctrine, which should replace the currently prevailing paradigm of “scope” with the paradigm of “core standards” and make EU rule of law requirements diagonally applicable via Article 2 TEU. The three layers of the proposed theory are presented in detail. The doctrinal analysis explores the ontological considerations and how these call for a selective and deferential approach as to the diagonal application. The textual-dogmatic analysis demonstrates that Article 2 TEU is a suitable entry-point for the diagonally applicable rule of law requirements. This is followed by an examination of the institutional aspects.

B. EU Rule of Law’s Diagonality: The Status of a Missing Concept

This section maps the missing diagonality of EU rule of law. First, it coins the term and gives a definition of the concept. Second, it reveals the internal contradiction in the EU’s constitutional architecture caused by the tension between the proclamation of fundamental values and the lack of diagonal application. Third, it demonstrates that EU rule of law is currently determined by the paradigm of “scope,” which—notwithstanding its substantial spill-over effects—is incapable of providing a comprehensive solution to the problem of diagonality.

I. What is Meant by Diagonality?

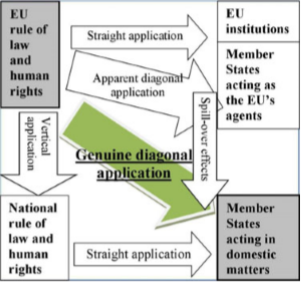

This Article coins a new term to describe the EU’s rule-of-law problem. Diagonality refers to the application of EU rule of law against Member States, as opposed to straight application, which refers to the application of EU law requirements against the EU (EU institutions and their national agents, that is, Member States implementing EU law), as well as the application of Member State requirements against Member States.

EU law contains a comprehensive set of rule-of-law requirements, which have a full application against the EU—straight application—but only a very limited one against Member States—diagonal application.Footnote 10

EU rule of law applies to Member States when they implement EU law, however, notwithstanding its substantial spillover effects, this diagonality is false, as here Member States act as the EU’s agents—apparent diagonal application—contrary to cases where EU rule of law is applied to Member States acting in their own field of operation—genuine diagonal application. The EU has a peculiar constitutional infrastructure where policy and institutional borderlines between the EU and the Member States are distant from each other. The EU has weak institutional and enforcement capacities and national authorities and courts have a predominant role in enforcing EU law. This dual role means that—when enforcing EU law—national authorities and courts are, in fact, acting on behalf of the EU.

II. European Constitutionalism’s Internal Contradiction

The EU’s constitutional architecture features a blatant contradiction when it comes to rule of law. Fundamental rights are protected as universal human interests—equality and dignity—but they are not directly enforceable among EU Member States.

On the one hand, while EU law generally requires Member States to respect rule of law and fundamental rights, it does not specify these requirements. While the expectations governing the actions of EU institutions are detailed, those applicable to Member State action are exhausted in the intensely general declaration of Article 2 TEU, which provides that the EU “is founded on the values of respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities.” Although the Charter of Fundamental Rights sets out the human rights to be protected, it is, for the most part, not applicable to Member States as such but to the Union—the Charter applies to Member States only when they are implementing EU law.Footnote 11 Even though EU law sporadically provides for the protection of rules of law and human rights against Member States, these make up no comprehensive solution.

On the other hand, the current European system, in relation to Member States, combines the naivety of a preachment and the simplicity of a bludgeon. While EU law asserts to place an extraordinary importance on core values, with Article 2 TEU calling them the foundation of the Union, no effective enforcement mechanism is attached to them. So long as no effective legal mechanism is attached to actually compel Member states to respect fundamental rights and freedoms. this remains an empty declaration. The nuclear bomb embedded in Article 7 TEU, which is a clause allowing the suspension of membership rights for human rights violations, is too brutal in terms of consequences and too unrealistic in terms of political feasibility.

It has to be noted that the main reason the diagonality problem is a pivotal question of the European “project” is not in itself the EU’s lack of power to effectively enforce rule of law in the Member States but rather the fact that these values are considered a ground of divorce. In essence, it is not the EU’s lack of competence but the accompanying displeasure of the community that makes this a crucial question for the European integration.Footnote 12

III. The Paradigm of “Scope” and the Current Missing Status of Diagonality in EU Rule of Law

Currently, the application of EU rule of law, as a matter of principle, is linked to the scope of EU law—paradigm of “scope”—and the debate on human rights in Member States has centered around how to define this scope. It is submitted that this approach is flawed. On the one hand, it is lacking as it does not provide protection in genuine domestic matters. On the other hand, it tempts EU institutions to overstretch the scope of EU law and in matters where EU rule of law is applied it is applied rigorously without taking into account national constitutional identities.

Although the Charter is the EU’s bill of rights, it is predominantly applicable to EU institutions; its scope extends to Member States only when they are implementing EU law.Footnote 13 The Charter does not aim to make sure that Member States respect human rights; it is meant to make sure that the EU exercises its powers and operates in a constitutional way. The idea of erecting human rights requirements against EU institutions is based on the notion that no public authority may exist without constitutional limits, and a considerable element of these limits are human rights.Footnote 14 Even though the CJEU has the tendency to construe the term “implementing Union law” fairly widely,Footnote 15 it has never questioned the above bifurcation.Footnote 16

Although EU rule of law has only apparent diagonal application, in that it applies to Member States when they act as the EU’s agents, this has at times momentous spill-over effects as regards Member State action. The independence of national judiciary is a good example (Portuguese Judges).Footnote 17 The independence and proper functioning of the national judiciaries does not emerge from the diagonal application of EU rule of law but from the effectiveness of EU law. National courts have a dual role in the sense that they are instrumental in applying both EU and national law. Due to the preliminary ruling procedure, they have a crucial role in the enforcement of EU law. Individuals usually cannot seek redress directly before the CJEU, and national cases reach Luxembourg through the mediation of national courts making references to the CJEU. As the independence of the judiciary as to EU and national law cannot be separated, Member States’ duties to secure their judiciaries’ independence for EU law, as a side-effect, inevitably implies the same for national law. It is a demand that national courts must be independent when applying EU law. As EU law and national law are applied by the same courts, the requirement of independence, which governs the application of EU law, also governs the application of national law. As a matter of principle, the EU law requirement is concerned solely with the cases where courts apply EU law.Footnote 18 However, as a matter of practice, because EU law and national law are applied by the same organization, this implies that national courts must be independent in general.

Another important element of the EU’s constitutional puzzle is the concept that Member States may use the exceptions provided by the internal market only if the restriction justified by the local public interest complies with EU rule-of-law requirements. A restriction of free movement, even if necessary and proportionate—that is, justified—is unacceptable if it goes counter to the foregoing requirements.Footnote 19 Given the highly extensive reach of the four freedoms,Footnote 20 this, in fact, extends EU fundamental rights to most national measures restricting economic activity.Footnote 21

The Commission also had to resort to “Al Capone tricks”Footnote 22 to foster rule of law in the Member States, using the verge of European rules and prohibitions. In these cases, the Commission “cooked from what it had”Footnote 23 and used the supportive by-effects of apparently unconnected EU norms. The “Al Capone tricks” hit the target in a few cases.Footnote 24

A notable example is Commission v. Hungary,Footnote 25 where the prohibition of discrimination based on age was used to protect the independence of the judiciary. Although this convoluted argument appears to have been needless in light of the CJEU’s recent ruling in Portuguese judges, at the relevant time the availability of 19(1) TEU for this purpose was uncertain.Footnote 26 In this case, Hungary reduced the mandatory retirement age for judges, public prosecutors, and public notaries from seventy to sixty-two. This resulted in the retirement of almost 300 judges and public prosecutors.Footnote 27 This was a highly perilous outcome for the independence of the judiciary, given that the mass dismissal and the ensuing mass recruitment of judges may have given the government an opportunity to influence the composition of courts. The concern for judicial independence was compounded by the fact that a good deal of the judges affected by the mandatory retirement were senior high court judges and supreme court justices. While the Commission was reluctant to base its claim on judicial independence, it successfully attacked the Hungarian provisions before the CJEU on the basis that they fell afoul of the principle of equal treatment. This was embedded in Directive 2000/78/EC, prohibiting discrimination at the workplace, among others, on grounds of age. The Commission doubted whether it had the power to address the primary issue directly, so it relied, successfully, on the EU prohibition of discrimination based on age. Tellingly, while the Commission wrapped up its legal arguments in the prohibition of discrimination, its press release announcing the launch of the infringement procedure leaves no doubt that it envisaged addressing judicial independence. In fact, the pertinent section of the press release is titled “Independence of the judiciary.”Footnote 28

Another notable example of supportive by-effects is the Slovak Language Law, which restricted the use of languages other than Slovak.Footnote 29 The law was criticized by different organizations from different human rights perspectives.Footnote 30 Nonetheless, the Commission objected to the law for thwarting the free movement of goods, persons, services, and capital and, thus, working counter to the EU internal market. Here, the application of the rules of the internal market had supportive by-effects for the language rights of minorities.Footnote 31

Apart from some sporadically guaranteed human rights, such as equality between men and women,Footnote 32 the only general mechanism providing for genuine diagonal application is Article 7 TEU, which sets out a lightly regulated political mechanism to address cases involving a clear risk of a serious breach of core EU values by Member States. This provision authorizes the Council to make a political decision, if found justified, but no meaningful sanction may be imposed without unanimity—of course, the Member State concerned is not included.Footnote 33 Furthermore, a huge weakness of Article 7 TEU is that it does not ensure EU human rights direct application in the Member States; it simply authorizes the Council to suspend certain membership rights.

Although Article 7 TEU is cherished as a nuclear bomb, it is rather a security valve, which is found wanting on at least three points:Footnote 34 It is unavailable in terms of practical feasibility, ineffective in terms of legal remedy, and summary in terms of legal consequences. Additionally, it creates a truly political mechanism lacking a normative character, which may be naturally subject to political criticism and national resistance.

It is a truism that enforcement of Article 7 TEU is politically unfeasible because any meaningful sanction postulates unanimity. Even though the Member State concerned cannot exercise its right to vote in its own case,Footnote 35 as a matter of practice, it would be difficult to imagine that no other Member States would veto an Article 7 condemnation, especially if this Member State is expected to be next on the docket.Footnote 36 Furthermore, even if a decision could be made, Article 7 TEU offers no redress but merely a sanction on the delinquent Member State. While a remedy may reinforce the trust in the EU, a sanction on the Member States may actually have a counterproductive effect and fuel nationalist sentiments in the case of a country that carries out a mutiny against Brussels and the European integration. The mechanism embedded in Article 7 TEU is summary and oversimplified; because of its political character and the general condemnation, it does not concentrate on the act but on the person, which may cause more harm than benefit. While the established metaphor for Article 7 TEU is a nuclear or atomic bomb, in reality, it is just a bludgeon.

IV. Scholarly Attempts

The scholarship is not devoid of proposals to extend the EU’s rule-of-law oversight of the Member States. Some argue that the scope of the Charter of Fundamental Rights should be extended, one way or another, to Member States in domestic matters.Footnote 37 Advocate General Jacobs argued in Christos Konstantinidis v Stadt Altensteig that EU citizens pursuing an economic activity in another Member State should benefit from the protection of EU rule of law.Footnote 38 In the same vein, it is argued that the Commission could bundle up a set of rule of law violations to present an Article 2 case, enabling it to launch an infringement procedure—systemic infringement procedure.Footnote 39

Nonetheless, authors have been struggling to forge a doctrine that reconciles the effective protection of EU rule of law with the required deferentialism to national constitutional identities. These inquiries were guided by the notion that the diagonal application should be limited, suggesting that the adequate solution will be found if one succeeds in delimiting full application from limited application in a meaningful and reasonable way. One attempt is conceiving the role of EU law as a macro-level oversight focusing on systematic issues and not individual remedy.Footnote 40 An alternative arrangement is making EU rule of law applicable with a qualification. The most well-known from these intellectual endeavors has probably been the Reverse Solange theory,Footnote 41 which qualified the applicability of the European human rights arsenal. Historically, the idea to link diagonal human rights protection to the concept of European citizenship and to reserve it for cases where the protection of fundamental rights in a Member State is gravely inadequate was first introduced by Advocate General Maduro in Centro Europa.Footnote 42 In the same vein, the Reverse Solange theory asserts that EU rule of law should have no application to a Member State as long as national law ensures a sufficient level of protection. In terms of direction, this is the opposite of the Solange approach of the German Constitutional Court,Footnote 43 under which, the acts of the EU would not be subject to German human rights review as long as EU law provides for a protection which provides a level that is “essentially similar” to that of German law.Footnote 44 The entry point of this theory was proposed to be the concept of EU citizenship.

The Reverse Solange theory proposes the application of EU rule of law but softens this with a qualification. It will apply only if there is a systemic failure in a Member State, which could also be a single but serious violation;Footnote 45 that is, the protection of rule of law collapses in a Member State—a circumstance that, by the way, could possibly give rise to proceedings under Article 7 TEU. In such a case, a Member State would be released from its duty to protect human rights on its territory.

While such a solution would represent an important progress and a major contribution to the development of EU law, it may appear to be lacunose for various reasons, especially in cases where the systemic violation, instead of a single but outrageous infringement, is based on a series of infringements. “The main problem, which thousands of EU citizens are facing, is not connected to the systemic meta-violations of rights, but to a myriad of most mundane ones, which are not dealt with by national authorities.”Footnote 46

First, if the judgment on the precondition—systemic failure—requires a comprehensive assessment, which occurs in the event EU law’s intervention is not triggered by a single but serious violation, EU courts may not be appropriately equipped to carry out this assignment. If the condemnation is based on a series of infringements, it would demand that EU courts make an overall judgment as to whether a Member State is a rule-of-law country and protects human rights appropriately. Second, because of the overall judgment on the state of rule of law and judging the person—in this case the Member State—and not only the specific conduct, there is a risk that the mechanism may be, notwithstanding its judicial nature, rather politicized. Third, in case the doctrine is applied because of a series of infringements, it may often be found wanting, as giving either too little, or too much. Before the breakdown of human rights protection is established, it fails to save individual victims. After that, due to the enforcement of EU rule of law, there is a risk that it might appear to encroach unnecessarily on national constitutional identities and Member States’ margin of appreciation. Fourth, the Solange approach appears to be much more plausible when applied to institutional arrangements as opposed to substantive standards; especially if it were argued that EU institutions should assume the duty to protect human rights in case national courts fail.

C. Comparative Law Models and Potential Paradigms

Fortunately, comparative federalism provides an array of experiences, solutions, and techniques which help the European integration to grasp and address the diagonal rule of law problem and to muster the available solutions. The spectrum of federal patterns is wide, ranging from federations based on the unitary normative nature of human rights—such as Austria, Belgium, and Germany—which may be designated as tight federal human rights systems, to countries that accommodate a more diverse set of human rights identities. Loose federal systems span a wide spectrum of patterns, ranging from Canada, where the Charter of Rights and FreedomsFootnote 47 applies equally to the federal government and the provinces,Footnote 48 to Australia, where there is no federal bill of rights at all. In between stands the United States (US), whose constitutional history appears to provide the closest parallelism to the European Union.

This section takes stock of the available patterns of diagonal protection of rule of law in two steps. First, it identifies those patterns that arguably do not comport with the demands of European integration and justifies their rejection. Second, it presents the US incorporation theory’s genesis and development as a mutatis mutandis employable pattern that has served as a source of inspiration for this Article’s proposed doctrine of European incorporation.

I. Dead Ends of Europeanization: Full Uniformization, Political Entrenchment, and Constitutional Silence

The straightest approach as to the diagonality of human rights is offered by tight federal human rights systems—such as in Austria, Belgium, and Germany—which feature a vertical application based on two structural principles. First, the federal list of rights—even if constituent states may have their own catalogs—is not confined to some minimum standards, but is meant to be comprehensive and exhaustive. Although states may have their own human rights systems, the federal community elaborated the federal list of rights with the purpose of being independent and complete. Second, the federally recognized rights have a uniform content giving no meaningful room to local variations—states have no special margin of appreciation different from that of the federal state.Footnote 49

This uniformization of human rights would be irreconcilable with the European way. First and foremost, while Member States did consent to some basic rule of law standards, which are pronounced the foundations of the EU by Article 2 TEU, it is obvious that they have never fully ceded this part of national sovereignty and have never subjected themselves to a full-fledged European human rights power. This would make the uniformization of rule of law requirements and the full application of the Charter to the Member States saliently contradictory. Second, the respect for constitutional identities and subsidiarity are fundamental principles of EU law having equal rank to the EU’s other core values and confine Europeanization.Footnote 50

Loose federal human rights systems use various methods to give room to regional “constitutional identities.”

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms does not distinguish between straight and diagonal application, and equally applies to the federal government and the provinces.Footnote 51 However, neither the depolitization nor the uniformization of Canadian human rights is as determinate as it may appear at first glance.

On the one hand, section 33 of the Canadian Charter (the notwithstanding clause) gives both the federal government and the provinces the right to unilaterally opt out from the Charter’s central provisions.

Section 33

-

(1) Parliament or the legislature of a province may expressly declare in an Act of Parliament or of the legislature, as the case may be, that the Act or a provision thereof shall operate notwithstanding a provision included in section 2 or sections 7 to 15.

-

(2) An Act or a provision of an Act in respect of which a declaration made under this section is in effect shall have such operation as it would have but for the provision of this Charter referred to in the declaration.

-

(3) A declaration made under subsection (1) shall cease to have effect five years after it comes into force or on such earlier date as may be specified in the declaration.

-

(4) Parliament or the legislature of a province may re-enact a declaration made under subsection (1).

-

(5) Subsection (3) applies in respect of a re-enactment made under subsection (4).

Although the unilateral opt-out can be made only for five years, it can be renewed as many times as the federal government or the province pleases. In the same vein, while the right to opt out is confined to section 2 and sections 7–15 of the Charter, in fact, these are the pith of human rights protection. Section 2 sets out the fundamental freedoms, such as “freedom of conscience and religion, freedom of thought, belief, opinion and expression, including freedom of the press and other media of communication, freedom of peaceful assembly, and freedom of association.” Sections 7–15 list the legal rights enjoyed before courts and law enforcement.Footnote 52 The rights from which no opt-out is possible are the democratic rights, sections 2–5, ensuring the right to participate in political activities and protecting the democratic form of government;Footnote 53 the right to free movement—mobility rights—of Canadian citizens in Canada, section 6; and language rights ensuring the use of English and French in communications with the federal and certain provincial governments and in education.

Although the provinces have made use of the notwithstanding clause only a few times and only temporarily— and in fact the federal government has never used this possibility,Footnote 54 making this provision’s application exceptional—the constitutional possibility exists. It is worthy of note that the notwithstanding clause embeds no specificity requirement. While provinces normally immunize specific pieces of legislation, in 1982 immediately after the adoption of the new constitution and the Charter, the province of Quebec made an omnibus declaration making all past and future québécois legislation immune from the Charter’s respective provisions.Footnote 55 Such a blanket application was found to be in conformity with section 33 of the Charter by the Supreme Court of Canada.Footnote 56

In contrast, federalism factored into the Charter and its caselaw at various points. First, the Charter contains no economic or social rights and may be conceived as a set of minimum standardsFootnote 57 instead of a bill of rights providing for a comprehensive and full rights protection, and provinces are free to have their own rights catalogs.Footnote 58 Second, section 27 of the Charter pronounces that the “Charter shall be interpreted in a manner consistent with the preservation and enhancement of the multicultural heritage of Canadians.” Third, while this did not develop into an explicit and specific doctrine describing the relationship between the federal bill of rights and federalism,Footnote 59 the judicial practice has shown considerable sensitivity to federalism.Footnote 60

From a European perspective, the Canadian constitutional pattern may appear to fall short of guarantees for provincial—national—constitutional identities and to be unduly permissive as to national political veto power. The Canadian federalization of human rights works effectively because of its political entrenchment emerging from the Canadian political consensus and the Charter’s social prestige.Footnote 61 The political veto power enshrined in section 33 has been used a few times but never in a perpetuated manner. Nonetheless, there is nothing to prevent a province from systematically, en bloc, immunizing its law with continuous renewal in case there is permanent political support in the provincial constituency.

Australian constitutional law features a pattern that can be presented as the antipole of uniformization: Constitutional silence. Namely, the Australian constitution contains no bill of rights, neither as to states nor as to the federal government. It contains a handful of fundamental rights, some of which limit only the federal government, some of which apply also to states.Footnote 62 Nonetheless, it clearly fails to build up a comprehensive system of human rights protection.

In this sense, the Australian constitutional architecture may seem to be similar to the current state of EU law in terms of sporadic rights protection. Regardless, this parallelism is false.

First, Australian states show a much lower level of diversity in terms of thinking about liberties, democracy, and social values than EU Member States. As an expressive example, Australia does have federal common law—a concept rejected even by the United States Supreme Court.Footnote 63 While in the US each state has its own common law, in Australia common law is a federal body of law.

Second, in Australia the Commonwealth has incomparably stronger legislative powers than the EU. Furthermore, under section 122 of the Australian Constitution, the territories are subservient to the Australian parliament and government. This enables the federation to get legislative—political—solutions to the eventual human-rights-focused tensions between federal and state/territorial political communities. For instance, contrary to the US and Europe, state sodomy laws were not quashed by judicial intervention but a legislative act. In the Toonen case, after a successful complaint submitted to the United Nations Human Rights Committee against Tasmania’s anti-gay laws,Footnote 64 the Commonwealth of Australia passed the Human Rights (Sexual Conduct) Act 1994 (Cth), which was designed to override the pertinent provisions of Tasmania’s criminal law.Footnote 65 The same legislative approach was taken concerning the 1995 euthanasia law of the Northern Territory,Footnote 66 which was the first to legalize assisted suicide. This law was suppressed two years later by an act of the Parliament of Australia, the Euthanasia Laws Act 1997 (Cth), which withdrew the power to legalize euthanasia.Footnote 67

II. United States Constitutional History: The Judicial Incorporation of the Federal Bill of Rights

The current EU architecture clearly parallels the first century of US constitutional history.Footnote 68 Although today, due to the incorporation doctrine, most fundamental rights valid against the federal government can be invoked also against the states,Footnote 69 the first century of US constitutional law reveals a federal approach similar to Article 51 of the EU Charter. Albeit that the US constitution sporadically established a couple of limits against states that may be regarded as human rights in nature,Footnote 70 the arsenal of human rights protection as enshrined in the US Constitution’s first ten amendments, the federal Bill of Rights, did not apply to states until the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment after the Civil War. For a century, states were limited only by the rules of state constitutions.Footnote 71

The parallelisms and similarities between the first century-and-a-half of US constitutional history and the current European architecture are manifold.

In both systems, the federal bill of rights—the EU Charter and the US Constitution’s first ten amendments—is the product of the same thinking, which is that no public power may exist without human rights clogs, and initially was introduced to limit the federal government without any endeavor to introduce a federal human rights watchdog power for the states. The founding fathers in both cases focused on creating a workable and fair system of federal government. Initially, the two unions were not created to protect human rights but to establish a federal government that can fulfill its functions.

In the US, the inclusion of a bill of rights into the constitution was rejected at the Constitutional Convention, but subsequently critical voices emerged against ratification arguing that power may be shifted only with human rights limits. The first ten amendments of the US Constitution were adopted after it became clear that ratification may not have occurred absent the inclusion of a bill of rights.Footnote 72

The US Supreme Court put this very clearly in Barron v Baltimore, decided more than three decades before the Fourteenth Amendment’s ratification:

The Constitution was ordained and established by the people of the United States for themselves, for their own government, and not for the government of the individual States. Each State established a constitution for itself, and in that constitution provided such limitations and restrictions on the powers of its particular government as its judgment dictated. The people of the United States framed such a government for the United States as they supposed best adapted to their situation and best calculated to promote their interests. The powers they conferred on this government were to be exercised by itself, and the limitations on power, if expressed in general terms, are naturally, and we think necessarily, applicable to the government created by the instrument. They are limitations of power granted in the instrument itself, not of distinct governments framed by different persons and for different purposes.

If these propositions be correct, the fifth amendment must be understood as restraining the power of the General Government, not as applicable to the States. In their several Constitutions, they have imposed such restrictions on their respective governments, as their own wisdom suggested, such as they deemed most proper for themselves. It is a subject on which they judge exclusively, and with which others interfere no further than they are supposed to have a common interest.Footnote 73

The EU Charter of Fundamental Rights walked the same path. The predecessor of the Charter had been the general principles of law—a concept developed by the CJEU, among others—to introduce human rights limits against the actions of the EU. They were not meant to control Member States. The purpose was to limit the power of the federal government. As in a democratic society no public authority may exist without human rights limits, the CJEU established very early that the EU has to respect human rights even if they were not explicitly provided for in EU law. It was evidently natural that public power goes hand in hand with human rights limits.Footnote 74 These court-developed human rights requirements culminated in the Charter—which was likewise not intended to be a general human rights “watchdog,” but a check on the EU’s federal government.Footnote 75 This approach informs the scope of the Charter as defined in Article 51. The extension of the Charter’s scope to Member States when they implement EU law is explained by the idiosyncratic European institutional architecture and reinforces the foregoing conception. Because the EU has no local administrative organs, Member States have a prominent role in enforcing EU law, and when they act as agents their actions are attributable to the EU.

The extension of the federal bill of rights to states—an accomplished fact in the US and a historical necessity in Europe—was and is inspired by a ground of divorce type of thinking. After the American Civil War, the Reconstruction Amendments proved that there are certain common core values which have to be respected throughout the Union, and there are certain practices that violate—to use conflicts law phraseology—the Union’s “most basic notions of morality and justice.”Footnote 76 This recognition fueled the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment, which provided for the applicability of a few federal fundamental rights to states. Interestingly, the idea of a bifurcated fundamental rights protection was so deeply entrenched in the American constitutional thinking that US courts rejected the extension for half a century. In United States v. Cruikshank, the Supreme Court held that the right to assembly, as enshrined in the First Amendment:

was not intended to limit the powers of the State governments in respect to their own citizens, but to operate upon the National Government alone, … for their protection in its enjoyment … the people must look to the States. The power for that purpose was originally placed there, and it has never been surrendered to the United States.Footnote 77

In 1897, the Supreme Court in Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad Co. v. Chicago used the Fourteenth Amendment to enforce “property protection” on states in the name of “substantive due process.”Footnote 78 The breakthrough was brought along in 1925, with Gitlow v. New York,Footnote 79 where the Supreme Court explicitly announced the doctrine of incorporation, in this case with express reference to the First Amendment.Footnote 80 This was followed by numerous cases extending the application of the federal Bill of Rights to states.

Accordingly, for nearly 150 years, the US federal Bill of Rights did not apply, or applied to a very limited extent, to states. The constitutional experience that entailed a shift in this system was the recognition that if states did not agree with one another in upholding certain rights, the system would be unsustainable. This idea found reflection in the case-law.

In Snyder v. Massachusetts, the Supreme Court held that a state is:

Free to regulate the procedure of its courts in accordance with its own conception of policy and fairness unless, in so doing, it offends some principle of justice so rooted in the traditions and conscience of our people as to be ranked as fundamental.Footnote 81

In the same vein, in Palko v. Connecticut, the Court held that:

The right to trial by jury and the immunity from prosecution except as the result of an indictment … are not of the very essence of a scheme of ordered liberty. To abolish them is not to violate a ‘principle of justice so rooted in the traditions and conscience of our people as to be ranked as fundamental.’ … Few would be so narrow or provincial as to maintain that a fair and enlightened system of justice would be impossible without them. What is true of jury trials and indictments is true also, as the cases show, of the immunity from compulsory self-incrimination…. This too might be lost, and justice still be done.Footnote 82

Although, subsequently, the Supreme Court incorporated the overwhelming majority of the rights listed in the first ten amendments, making non-incorporated rights an exception, the first decades of the doctrine, which have featured the approach of selective incorporation,Footnote 83 reveal how the Court tried to separate diagonally applicable rights from federal liberties limiting only the federal government.

The history of the Fourteenth Amendment is very instructive for the European integration, though the controversies between the EU and a few Member States concern less flagrant violations of human rights than the ones that gave rise to the Fourteenth Amendment, such as slavery and racial discrimination. The trajectory of this development, starting with a constitutional amendment and ending with nearly full incorporation, provides a myriad of lessons—patterns to follow and patterns to avoid.

It is no exaggeration to say that the Fourteenth Amendment proved to be successful in guaranteeing national fundamental rights in the United States and strengthening the link between the states and the Union with a further element. Although it contains both a judicial and a judicially controlled political mechanism, courts have carried the day in this process. At the end of the day, it was not the political branch and not quick and summary political solutions that did away with the human rights deficit but the courts. Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment lists a few selected and judicially enforceable rights that are to have diagonal application to states,Footnote 84 while section 5 confers on the Congress the “power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this Article.” Both prongs are judicially controlled. Section 1 is the subject of individual litigation, while the exercise of the legislative power conferred by section 5 is controlled by the court. Congress may not introduce new rights and may not change their content. Its power is limited to the enforcement of the liberties enumerated in the Bill of Rights, and the requirement of “appropriate legislation” implies that the law adopted shall be proportionate and have a “remedial” purpose:

Congress’ power under § 5, however, extends only to “enforc[ing]” the provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court has described this power as “remedial.”. The design of the Amendment and the text of § 5 are inconsistent with the suggestion that Congress has the power to decree the substance of the Fourteenth Amendment’s restrictions on the States. Legislation which alters the meaning of the Free Exercise Clause cannot be said to be enforcing the Clause. Congress does not enforce a constitutional right by changing what the right is. It has been given the power “to enforce,” not the power to determine what constitutes a constitutional violation. Were it not so, what Congress would be enforcing would no longer be, in any meaningful sense, the “provisions of [the Fourteenth Amendment].”Footnote 85

It must be stressed that although section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment confers a legislative power on the Congress, it depoliticizes it as far as possible. The aim of this power is not the general condemnation of a state on human rights grounds. Section 5 has a positive function: It addresses systematic human rights violations without empowering the political branch to pronounce “collective guilt”:

If Congress could define its own powers by altering the Fourteenth Amendment’s meaning, no longer would the Constitution be “superior paramount law, unchangeable by ordinary means.” It would be “on a level with ordinary legislative acts, and, like other acts, … alterable when the legislature shall please to alter it.” … Under this approach, it is difficult to conceive of a principle that would limit congressional power…. Shifting legislative majorities could change the Constitution and effectively circumvent the difficult and detailed amendment process contained in Article V.Footnote 86

The American approach is in sharp contrast with the current European architecture, which provides very limited possibility for individual litigation. This is available chiefly in case a Member State, at least partially, implements EU law, and features a truly political and judicially uncontrolled mechanism to condemn a Member State for the systematic violation of fundamental rights. The recent proposal to make EU funding conditional on rule of lawFootnote 87 fits perfectly in this line: A summary political mechanism to condemn a Member State for its illicit attitude without providing any remedy. Of course, it would be highly unfair to blame the EU institutions for this because they cook with what they have and have used their powers in the most creative way to protect the Union’s fundamental values.Footnote 88 It appears to be clear, however, that a sustainable solution cannot be attained without reforming the current legal and institutional architecture. The Fourteenth Amendment’s two-prong approach—individual litigation limited to a set of core rights violation of which amounts to a ground of divorce, and a positive legislative power to enforce these rights against systematic violations—is very instructive in this regard.

American constitutional history also provides a caveat for Europe. While this has not always been the case, at the end of the day the Fourteenth Amendment practically unified human rights law in the United States. Subsidiarity and state constitutional identities could have been given room in two ways: Incorporating only a part of the enumerated rights and interpreting the incorporated rights in a more flexible manner to afford states a certain margin of appreciation to display local values and ideas. After a period of balking, both of these were rejected. Although the Supreme Court was, for a long time, wavering between total and selective incorporation, in the end, it incorporated the vast majority of the rights listed in the first ten amendments.Footnote 89 It is true that some of the liberties of the federal Bill of Rights are not incorporated, but they are very few. For the time being, most fundamental rights valid against the federal government can also be invoked against states under the incorporation doctrine.Footnote 90 States are, of course, free to have a more generous rights catalogue. However, they may not depart from the national liberties applied via the Fourteenth Amendment.Footnote 91 Furthermore, the doctrines of margin of appreciation, subsidiarity, and constitutional identity are alien to the Supreme Court’s bill of rights caselaw.Footnote 92

D. Proposal for a European Doctrine of Incorporation

To this point, this Article has demonstrated that, with the exception of the unfeasible mechanism of Article 7 TEU, the application of EU rule of law to Member States has been consistently conceived in the paradigm of scope—that is, EU rule of law applies in matters coming under the scope of EU law. Although the scope of EU law has been, at times, constructed extremely widely and this generated huge spillover effects on matters outside the scope of EU law,Footnote 93 the result of this approach has been—in an increasing number of cases—saliently unsatisfactory. This Article proposes to replace or complement the paradigm of scope with the paradigm of core standards.

This section advances this Article’s proposal for a European doctrine of incorporation. The proposed theory draws on the American incorporation of the federal bill of rights. It is argued that this provides the closest point of reference, though not a ready-made pattern, for disentangling Europe’s rule of law predicament. The theory of European incorporation is presented through its doctrinal, textual-dogmatic, and institutional layers.

First, this Article demonstrates that incorporation is warranted in EU law for two compelling reasons. The principled consideration is that respect of rule of law is considered to be a cornerstone of the EU—it is part of the EU’s identity—and its ignorance amounts to a ground of divorce. The practical consideration is that the latter may also undermine the practical operation of the European mechanisms, such as mutual trust, cooperation, and recognition in the field of civil and criminal justice or the decentralized enforcement of EU competition law. It is demonstrated that these ontological considerations also shape the diagonal purview of EU rule of law. Contrary to the straight application against EU institutions, diagonal application should be restricted to what is considered to be the baseline of EU rule of law—EU’s rule-of-law identity.Footnote 94 This implies that not all fundamental rights included in the Charter should be incorporated, and even with those which are incorporated, Member States’ margin of appreciation should be respected.

Second, this Article demonstrates that Article 2 TEU serves as a suitable textual-dogmatic entry point for the proposed doctrine of selective incorporation. Article 2 TEU, while having a very general language, is built up of terms—rule of law and human rights—that are sufficiently defined and elaborated in EU law and, hence, meet the requirements of direct effect and justiciability.

Third, this Article demonstrates how the proposed doctrine of European incorporation fits in the EU’s institutional architecture.

I. Doctrinal Layer: The Ontological Questions of Diagonality

The first and foremost question of the diagonality of EU rule of law is its raison d’être.

The ontology of the federal bill of rights’ application to the federal government is clear: No public power may exist without constitutional rule of law limits. The roots of the thinking that public authority is not limitless goes back well before the enlightenment.Footnote 95 Still, the latter introduced two innovations. First, it made the limits tighter and the state’s playing field narrower. Second, it replaced divine law and religious thoughts, among others, with human rights accruing from natural law. According to the idea of social contract, people ceded—or more precisely, if they had concluded a social contract, they would have ceded—Footnote 96 some of their rights to the state, but they reserved their inalienable human rights.Footnote 97 In this thinking, public power, human rights, and democratic control go hand in hand.

Nevertheless, this gives no guidance as to why federal human rights should be applied diagonally. As the EU confers no power on states, it can also not limit Member States in exercising their public power. Quite the contrary, because the genesis of federations by aggregation, such as the EU, are based on states’ conferring some of their powers on the federal entity, it is the states who should worry about the human rights limits of the federal power—as US states did and supplemented the US Constitution with the first ten amendments making up the federal bill of rights.Footnote 98

To find an answer to this question, one does not have to go very far. It suffices to simply observe why certain Member States’ rule of law backsliding has been criticized and opposed so emphatically and why it has been insisted that Member States comply with the EU’s core values. The critics of national backsliding, consciously or sub-consciously, asserted that fundamental values, such as rule of law, are part of the EU’s identity; they are the rules of the club and, as such, are part of the club identity, and members are expected to respect them. To put it another way, these values keep the Union together and their infringement is a ground of divorce.Footnote 99 This is reinforced by the languages of the EU’s constitutional instruments. Article 2 TEU calls these values the foundation of the Union, implying that if they fall out that would make the whole structure collapse. The preamble of the Charter pronounces them the EU’s “spiritual and moral heritage.”Footnote 100

Of course, the reason why the EU has a human rights problem is not that it lacks the power to effectively protect fundamental freedoms and rule of law against its Member States but instead that the public feeling is that such a power is needed to keep the Union together. Regional economic integrations operate without internal human rights watchdogs. And what is more, this approach is not alien to federal systems either. For instance, the Australian constitution contains no bill of rights.Footnote 101 The reason that turns this plight into a central issue and major challenge is not the encroachment on the fundamental freedoms. Instead, it is the sentiments generated in the community of states. Slavery has been one of the most disgusting and immoral practices of mankind. Still, the reason why this became one of the leading forces resulting in the American Civil War and the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment afterwards was that slavery was loathed by the Union at large. The Northern states not only rejected slavery on their own territories, but rejected it everywhere, as they regarded the abolition of slavery as a universal value.Footnote 102 That is, the source of the problem is not the local attitudes but the tension between the federal values and the local attitudes. This problem-setting shall determine the solution.

Accordingly, the fundamental reason that the diagonality problem has become so pivotal in the context of European integration is not the lack of power to effectively enforce rule of law in the Member States, but the fact that the community considers these values a ground of divorce. It is not the lack of competence but the community’s accompanying displeasure that makes this a pivotal question for the European integration, and this circumstance should shape the approach employed to solve the problem itself. There is no reason to make EU rule of law in the diagonal relation so uniform and exhaustive as in the straight relation, when it is applied to the EU. The purpose of the diagonal application is different—it is meant to create a baseline ensuring mutually tolerable arrangements in the Member States and to lift any possible centripetal tendency.

Having said that, it must be stressed that not only idealistic and value-driven considerations justify treating the EU’s core values as non-negotiable. If Member States did not share the EU’s common values, the EU would, for many reasons, become inoperative.

The European judiciary would be a torso without national courts, whose independence, reliability, willingness, and freedom to make references to the CJEU are an essential element of the EU’s justice system.Footnote 103 In the same vein, the EU has no regional or territorial bodies and needs to rely on the assistance of local administrative authorities. A good example is the decentralized enforcement of EU competition law. After realizing that the Commission cannot go after each case that arises, a decentralized enforcement system was created to reinforce European competition law with the use of national administrative capacities.Footnote 104 If national competition authorities are under political influence and effective remedy by national courts is not secured, then decentralization, in fact, spoils European competition enforcement instead of making it more effective.Footnote 105

Likewise, various forms of cooperation, in particular the achievements in the field of civil and criminal justice, largely based on the principle of mutual trust, would be seriously undermined. As stressed by the CJEU in Portuguese judges:

According to Article 2 TEU, the European Union is founded on values, such as the rule of law, which are common to the Member States in a society in which, inter alia, justice prevails. In that regard, it should be noted that mutual trust between the Member States and, in particular, their courts and tribunals is based on the fundamental premise that Member States share a set of common values on which the European Union is founded, as stated in Article 2 TEU.Footnote 106

Recognition of sister-state judgments, judicial assistance, and extraditions can be a reality only if it is out of question that the core values are respected throughout the Union. It is impossible to create a justice area where national court judgments move freely and benefit from full faith and credit if these courts do not trust each other without reservation. Intra-EU extraditions cannot be expected to be a routine if there is even the slightest doubt that defendants may not be granted a fair trial.Footnote 107

The ontology of the diagonal application shapes its operation. When the federal bill of rights is applied to the federal government, there is no reason not to apply the federally recognized human rights at full length. Nonetheless, the diagonal application has much more limited aims: It is destined to keep the Union together and to ensure mutual trust and recognition.Footnote 108 It could be said that the federal bill of rights’ straight application is destined to achieve a perfect world, while the diagonal application contents itself with tolerable results.

It is subconsciously understood that the full application of the Charter would be contradictory. Member States have never fully ceded that part of their sovereignty and have never subjected themselves to a full-fledged European human rights power. It is also undeniable, however, that Member States did make rule of law promises,Footnote 109 so even if no full EU power was accepted, some limited power was accepted. The scholarship has struggled with delimiting full from limited European rule-of-law power, understanding that if we find the legitimate limiting principle we have extracted the judiciable meaning of Article 2 TEU.

This implies the need for a partial incorporation as to the rights included and the construction of these rights—a selective incorporation of the human rights recognized by EU law and the respect of the Member States’ margin of appreciation when it comes to the diagonal application of EU rule of law.

In contrast with the rather homogenizing American caselaw, the European landscape calls for a fundamental rights protection pattern that is effective, but at the same time does not suppress national constitutional identities and accommodates national sensitivities.Footnote 110 For instance, Catholic traditions play a pivotal role in the Irish constitutional identity;Footnote 111 though same-sex marriages are available in quite a few Member States. In a few states such as Hungary,Footnote 112 Slovakia,Footnote 113 and Poland,Footnote 114 the constitution limits marriage to opposite-sex couples; in the former socialist Member States there is a special sensitivity against the red star.Footnote 115 Of course, the core of human rights protection cannot be subject to territorial variations and the violation of the nucleus of these rights cannot be justified with reference to constitutional identity.

The Charter contains rights, in particular the economic and social rights listed in Title IV,Footnote 116 that may be legitimately amenable to regional variations and, hence, selective incorporation is justified. Furthermore, at times, certainly not always though, you can have your cake and eat it too. The treatment of same-sex marriages by the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) demonstrates this well. In Obergefell v. Hodges, the US Supreme Court held that all states are required to register and recognize same-sex marriages.Footnote 117 On the contrary, the ECtHR adopted a more deferential but still protective approach. It held that the status of same-sex couples has to be recognized but states are not obliged to call this status a marriage. States have to afford a more or less comparable status to same same-sex couples,Footnote 118 but they are not obliged to use the label of marriage.Footnote 119 They may do this under the notion of civil union or registered partnership. In other words, the ECtHR protected the status of same-sex couples to the utmost extent but also tried not to interfere with the national sensitivities. In Schalk and Kopf v. Austria, the Court “observe[d] that marriage has deep-rooted social and cultural connotations which may differ largely from one society to another [and] it must not rush to substitute its own judgment in place of that of the national authorities, who are best placed to assess and respond to the needs of society.”Footnote 120

II. Textual-Dogmatic Layer: The Direct Effect of Article 2 TEU

The textual-dogmatic question relies on whether and how the doctrine proposed above may find its way into positive law.Footnote 121 Notably, without an appropriate entry point, the proposed doctrine of ground of divorce may not be anchored in EU law and would be, at most, a de lege ferenda proposal in a matter where achieving unanimity is highly unlikely and constitutional amendments hold out little hope.

Unfortunately, the mainstream dogmatic approach of EU law gives a very narrow playing field. It is generally accepted that, notwithstanding the various significant but sporadic rule-of-law requirements that EU law erects against national action, Member States are not subject to any comprehensive regime. Although the CJEU has interpreted the term “implementing EU law” widely, the language of Article 51 of the Charter makes it difficult to stretch the scope of the EU bill of rights to cover all European grounds of divorce. Nonetheless, EU law does contain a suitable entry point for Europe’s core rule-of-law and human rights principles: Article 2 TEU, a provision that has been largely overlooked due to its general language.Footnote 122

This Article will demonstrate in two steps in the text below the suitability of Article 2 TEU to serve as an entry point for EU rule of law. First, the pre-conditions of direct effect will be established, and this Article will demonstrate that, over time, the doctrine evolved into a question of justiciability. Second, this Article will demonstrate that Article 2 TEU is justiciable, as it uses terms and concepts sufficiently defined by EU law and, hence, may serve as an entry point for the doctrine of ground of divorce.

It is worthy to note that if Article 2 TEU opened the door for EU law to create a rule of law baseline for Member States, that may be an impetus for Member States to work out the conceptual architecture of diagonality via a treaty amendment. An interesting parallelism is offered by EU merger control law. For roughly four decades, EU competition law contained no rules on merger control and was satisfied with having rules on restrictive agreements and abuse of dominant position only. Even though this was a major shortcoming, Member States refused to cede this competence to the EU. In 1987, however, the CJEU sanctioned the Commission’s banning a merger as a restrictive agreement under Article 101 TFEU.Footnote 123 The judgment, although logical, generated a huge uproar and Member States, driven by the fear that without appropriate statutory rules the Commission and the CJEU themselves may work out the law on concentrations, adopted the first ever European merger control regulation.Footnote 124

1. Direct Effect: A Justiciability Question

The crucial dogmatic issue of European incorporation is the direct effect of Article 2 TEU. Obviously, if Article 2 TEU has no direct effect, it is not capable of serving as an entry point for EU rule of law. Though there is nothing in EU law stopping the Commission from launching infringement procedures against Member States if they violate EU norms having no direct effect. Alternatively, if this provision has direct effect, the door to EU courts opens and it must be applied by national courts and authorities.Footnote 125 The questions whether Article 2 TEU is sufficiently clear to have direct effect and whether it may function as an entry point for EU rule of law intermingle: the language of this provision is rather vague, and it becomes clear and justiciable because of the interpretative framework built up by sources of EU law that are external to Article 2 TEU.

The doctrine of direct effect is probably one of the foundational principles of EU law ensuring—together with the doctrine of supremacyFootnote 126 —that EU norms can be invoked before national courts and authorities. Although direct effect has never covered all provisions of EU law and has been subject to pre-conditions from the outset, these pre-conditions gradually evolved into a general requirement of justiciability.Footnote 127 As a rule of thumb, all EU law norms save for the ones inapt for judicial interpretation have direct effect.

Initially, the doctrine of direct effects was meant to embrace a significantly narrower set of norms than justiciable rules. In Van Gend en Loos, the CJEU set out a few pre-conditions for direct effect: The norm of EU law needs to be clear, unconditional, inclusive of a negative obligation, and qualified by no reservation on the part of the Member State making its implementation dependent on any national implementing measure.Footnote 128 Subsequently, however, the CJEU significantly watered down these pre-conditions.

The requirement of negative obligation reflected the fact that Van Gend en Loos dealt with the stand-still clause embedded in Article 12 EEC Treaty, which froze national tariffs rates for an interim period of ten years, at the end of which, they were fully abolished.Footnote 129 This requirement lost its relevance after the Court held, for instance, that individuals may rely on provisions in directives that set out procedural obligations for Member States, such as prior notification and environmental impact assessments, to oppose the validity of national measures adopted in violation of these procedural requirements.Footnote 130

[W]here the Community authorities have … imposed on Member States an obligation to pursue a particular course of conduct, the effectiveness of such an act would be diminished if individuals were prevented from relying on it in legal proceedings and if national courts were prevented from taking it into consideration … in determining whether the national legislature … had kept within the limits of its discretion.Footnote 131

An established phrasing of direct effect was that it gives ground to EU norms conferring rights on individuals and, accordingly, the doctrine of direct effect is destined to assure that national courts and authorities protect these EU rights. This conceptualization was gradually overcome, however, and gave ground to the idea that direct effect governs EU norms that can be invoked before national courts and authorities.Footnote 132 This conceptual twist appears to be plausible—rights and obligations are inseparably fused—Member States’ obligation not to impose tariffs implies the right to tariff-free trade, while the right to tariff-free trade implies an obligation to refrain from imposing tariffs.

The requirement of being clear and unconditional went through a similar melting. Reserving direct effect for crystal clear norms having no give of interpretation would have excluded a good deal, if not the majority, of EU norms. Even if the uncertainty of interpretation is included in the norm on purpose to afford Member States a margin of appreciation, there is no reason not to subject national action to a deferential EU law review examining the limits of this discretion and the consistency of balancing,Footnote 133 in the same way as the CJEU reviews Member States’ use of the exceptions to the free movement rights guaranteed by the internal market,Footnote 134 the ECtHR reviews national measures where states have a recognized margin of appreciation and administrative courts review administrative agencies’ discretionary acts. If an EU law norm affords Member States a certain margin of appreciation, they may enjoy a wider playing field but are not completely freed of legal clogs.

Member States’ possibility to choose does not preclude direct effect:

[T]he right of a State to choose among several possible means of achieving the result required by a directive does not preclude the possibility for individuals of enforcing before the national courts rights whose content can be determined sufficiently precisely on the basis of the provisions of the directive alone.Footnote 135

Due to the above developments, the Van Gend en Loos requirements, while leaving their imprints on the caselaw, were reduced to a general justiciability question:

Today, although the criteria used by the Court still vaguely echo those in Van Gend en Loos, the only thing required is that a national court, with the possible preliminary help of the ECJ, is able to apply the provision so as to determine the outcome of the case in hand.Footnote 136

As Advocate General Van Gerven puts in British Coal Corporation:

[P]rovided and in so far as a provision of Community law is sufficiently operational in itself to be applied by a court, it has direct effect. The clarity, precision, unconditional nature, completeness or perfection of the rule and its lack of dependence on discretionary implementing measures are in that respect merely aspects of one and the same characteristic feature which that rule must exhibit, namely it must be capable of being applied by a court to a specific case.Footnote 137

2. Is Article 2 TEU Justiciable?

Probably the first thought that comes to the mind of the reader of Article 2 TEU is that it is a political declaration with little or no normative content.Footnote 138 Indeed, the utmost constitutional importance of Article 2 and its normative strength are reversely proportionate. One may argue that this is a provision that could be better placed in a preamble: The European Union “is founded on the values of respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, rule of law, and respect for human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities.” A closer look at the text, however, suggests that the values listed here are taken much more seriously than a general recognition usually indicated in the preambles of international treaties. For example, the language, “recognizing that …” is often found in the preambles of international treaties. After all, Member States consider these values to be foundational, thus implying their ignorance may make the whole structure collapse. Furthermore, the fact that Article 7 TEU contains a mechanism for the enforcement of Article 2 TEU clearly indicates that the latter does embed legal obligations for the Member States.Footnote 139

The biggest problem with the direct application of Article 2 TEU is its uncertain nature and use of apparently undefined legal terms. To put it ironically, Article 2 says that there are things that are extremely important but fails to disclose what those things are. Nonetheless, this uncertainty and indetermination evaporates if we subject this provision to a statutory interpretation employing the most traditional legal methods. Notably, while Article 2 TEU tells us very little on the level of strict textual analysis, external sources of EU law do fill this gap of interpretation. Approaching a provision from this angle is neither novel, nor unknown. It is widely accepted that statutory interpretation has four layers—grammatical, logical, historical and systematic—and if statutory language is not clear or unequivocal, external legal norms, definitions, logic, and legislative purpose may also be used to find the proper meaning. The content of a provision having the most general language may be judicially ascertainable, or even unequivocal, if it uses terms defined by other provisions of the law.

Indeed, if reading them with blinders, “rule of law” and “human rights” may appear to be undefined legal terms. However, EU law is a coherent system and has to be interpreted as such. The CJEU had no scruples treating these concepts as directly effective when applying the general principles of law, an amorphous judge-made source of EU norms. In the same vein, national constitutions often, if not mostly, do contain provisions having a similarly elusive language. Myriads of examples could be given. The German Fundamental Law (Grundgesetz) pronounces human dignity to be inviolableFootnote 140 without giving any textual indication as to what human dignity means. A similar reference can be found in the Spanish Constitution.Footnote 141 The French Declaration of the Rights of the Man and of the Citizen of 1789 provides that “[m]en are born and remain free and equal in rights” without specifying what that freedom means.Footnote 142 The Hungarian Fundamental Law declares that Hungary is a rule-of-law state,Footnote 143 without giving any hints about the content of this concept. In this sense, Article 2 is not less defined than some of the provisions of national constitutions and its general language does not derogate from its justiciability. The relevant question is not whether Article 2 TEU, itself, has a clear meaning, but whether a sufficiently clear meaning can be attributed to it on the basis of EU law. From this perspective, it is irrelevant whether Article 2 itself defines what it means by “rule of law” and “human rights”; it obviously contains no definition. The main point is whether the meaning of these terms is sufficiently clear in EU law to make them justiciable.

As statutory “blanket fact patterns”—Blankett-Tatbestand—are completed in criminal law with the incorporation of rules and concepts of legal sources external to the criminal code, Article 2 may serve as an entry point for EU law’s various rule-of-law provisions. If this construction complies with the very stringent principles of criminal law, it should a fortiori be valid in other fields of law.

As discussed above, the US Supreme Court used the Fourteenth Amendment and specifically the concept of due process to incorporate the overwhelming majority of the rights and liberties listed in the first ten amendments—also known as the US Bill of Rights. From a textual perspective, incorporating the Charter into Article 2 TEU would be, by far, more obvious than incorporating the bill of rights included in the first ten amendments into the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process clause when due process is also listed in the Fifth Amendment as a specific liberty.

EU law does contain a set of detailed rule-of-law requirements which have been part of this legal system from the beginning. The CJEU considered fundamental principles of law to be one of the primary sources of EU law and pulled rule of law into the sphere of EU law. With the comprehensive codification of EU human rights in the form of the Charter of Fundamental Rights, these standards became much clearer. The Charter’s scope is limited, in that it applies to EU institutions and binds Member States only when they are implementing EU law. But it contains a clear and complete list of the fundamental rights recognized by the Union.

It must be noted that the proposed construction of Article 2 TEU would not be unprecedented in EU law. In fact, the CJEU has incorporated EU human rights and pronounced them having direct effect already twice in situations that involved way more uncertainty than the incorporation of the Charter’s codified human rights provisions, not to say that in these cases the Court did this on the basis of the general principles of law.

First, in Wachauf, the CJEU established that even though EU human rights requirements apply in principle to EU institutions, they also govern Member State action when the latter implements EU law.Footnote 144 This notion is subsequently included into Article 51 of the Charter. On the one hand, interestingly, the CJEU pronounced the Member States’ duty to respect EU human rights without any specific statutory basis and did not even examine the question of direct effect of these requirements. On the other hand, Article 2 TEU specifically invites EU rule of law, which are, due to the Charter, not judge-created doctrines anymore. Stating it otherwise, if incorporation and direct effect could be validly deduced in Wachauf, this should be valid as to Article 2 TEU too.

Second, in ERT,Footnote 145 human rights were incorporated and pronounced directly effective in a case paralleling the diagonality question even more closely. Here, the CJEU held that a Member State may use local public interest to justify the restriction of one of the four freedoms—an exception generally recognized by EU law—only in case its action is in compliance with EU human rights. In other words, the Court read EU human rights into the various exceptions to free movement. It must be noted that here the CJEU extrapolated EU human rights requirements to Member States without any textual basis, contrary to Article 2 TEU, which does contain an explicit reference.

III. Institutional Layer: Judicialization and Depoliticization

In the EU’s current institutional architecture, the political elements have an excessive role, while judicial enforcement is marginalized. The only comprehensive and straightforward means to address rule of law issues in the Member States is Article 7 TEU, a truly political mechanism, which may be used to address general backsliding but whose radar does not perceive individual violations, however outrageous they are. The sporadically available provisions of EU law, especially if they are backed by Al Capone tricks, are, at most, second best solutions for the protection of human rights. Their employability is unpredictable and implies the risk that the application of the law may be distorted by extraneous motivations, let alone that they may give rise to accusations of political nature.

It would be essential to complement the above toolkit with genuine judicial mechanisms which are, otherwise, generally available for the enforcement of EU law. This judicial enforcement meets two demands: It is capable of addressing both individual and systematic violations, and is depoliticized. Preliminary ruling procedures may be used in cases where individual remedy is sought, while infringement procedures are tailored to handle systematic issues.