A. Introduction

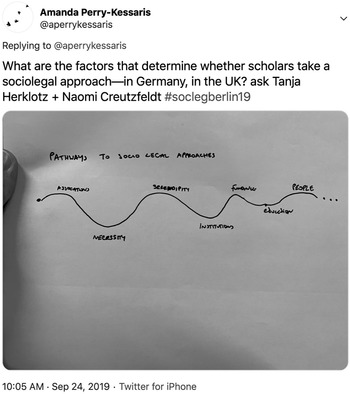

A central theme motivating the 2019 workshop on “Socio-Legal Studies in Germany and the UK: Theory and Methods”—from which this Special Issue emerged—was “how academic traditions and institutional contexts have influenced the development of socio-legal research in Germany and the UK,” and whether there exists a “typical pathway into and through law and society research” in each jurisdiction. During discussion, repeated note was made of a tendency among German academic institutions to be relatively structured or rigid—both in their definitions and assessments of legal research, and in their expectations around publishing and career pathways—and it was argued that this influences the inclination and ability of researchers to follow where their intellectual curiosity might lead. By contrast, it was observed, researchers in the UK benefit from a greater freedom to pursue the topics and methods of their choosing. As Stefan Machura details elsewhere in this Special Issue, this divergence manifests in the fact that, although German Rechtssoziologie began earlier, the UK variant, socio-legal studies, is stronger—a difference he attributes to the fact that socio-legal studies is defined more broadly, and there is a “greater openness” to “ideas from other disciplines in the UK.”Footnote 1 As a UK-based academic, I can confirm that my personal experience—shaped, of course, by a particular constellation of factors such as time, place, economics, and identity—has been one of freedom, and especially recently, of support to go my own way. Most notably, I have been able to devote substantial time and research funds over the last twenty-five years to train in other disciplines; and my attempts to draw insights from those disciplines have generally been received as legitimate by the UK socio-legal research community. That curiosity-driven, somewhat “serendipitous”Footnote 2 journey has led me to an ongoing project, Doing socio-legal Research in Design Mode, which explores the potential of design to help us to understand and enhance socio-legal research methods.

My interest in the intersections between law and design was triggered by frustration at the lack of communication among law, economics, sociology, and development studies.Footnote 3 Between 2012–2017, I became a part-time student of visual communication and then graphic design at the University of the Arts, London. A key insight I took from those years spent as a student of design is that “designerly ways”—that is, the mindsets, tools, and processes that are characteristic of design—are more inherently “social” than legal ways. I began to investigate the potential of designerly ways to make socio-legal research more “social.”Footnote 4

Reflecting back on the workshop discussion, two questions arise for me—one retrospective and inward-looking, one prospective and outward-looking—around which I will structure this Article. First, what signs of Anglo-German life can I find in the literature and practice underpinning my current research into socio-legal research and design? Second, might design have a role to play in nurturing a sense of Anglo-German socio-legal community?

B. Anglo-German Concepts and Norms

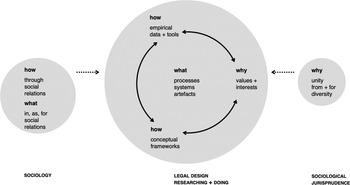

Any approach to law can be categorized in terms of what, substantively, is approached—for example, legal text, context, and/or subtext; how it is approached, both empirically and conceptually; and why it is approached—that is, motivated by what values and interests (Figure 2).Footnote 5 My wider project on “doing socio-legal research in design mode” focuses primarily on how designerly ways (mindsets, tools, processes) might enhance how (empirically, conceptually) we do socio-legal research; and in so doing, to better promote whichever values and interests we may seek to promote through our research. Here, I emphasize the Anglo-German influences on the conceptual (not empirical) dimensions of my work (how); and on my normative agenda (why).

Figure 1. Visual summary of discussion on pathways to socio-legal scholarship in the UK and Germany at “socio-legal Studies in Germany and the UK: Theory and Methods”.

Figure 2. Excavating the Anglo-German roots of Doing socio-legal Research in Design Mode.

I. Concepts

socio-legal researchers conceptualize the world, including law, in terms of social relations and the values and interests that underpin or motivate them. Like many in the UK and beyond, I tend to think in terms of the typology proposed by German sociologist and jurist, Max Weber, to distinguish between values and interests that are “instrumental” (for example, motivated by a purpose or task), “belief-based” (for example, motivated by religion), “affective” (for example, motivated by love) or “traditional” (for example, motivated by custom).Footnote 6 As populations have diversified and the complexities inherent in notions of national identity have been exposed, so it has become necessary to identify more flexible units of social analysis. Here, I draw on UK sociologist and legal philosopher Roger Cotterrell, who has long argued that we ought to look less for “society” and more for “communal networks”—that is, for those patterns of relatively sustained and trusting interactions, centering on any of the values and interests identified by Weber, in which each of us is (typically multiply) engaged.Footnote 7 This is the lens through which I think about both the social life of law, especially law as a communal resource; and the socio-legal research process, especially socio-legal researchers as forming an (instrumental, but also potentially affective) communal network.

II. Values and Interests

Why do we (or ought we to) do socio-legal research—what values and interests does it (ought it to) serve? What is its function? For me, the most useful and meaningful answers to this question—at least in the English language—are to be found in Cotterrell’s recent work on sociological jurisprudence, which—like his earlier work on law’s role as a communal resource—is built on German foundations.Footnote 8

In Sociological Jurisprudence, Roger Cotterrell celebrates the role of “jurists”—that is, thoseFootnote 9 who, first, approach law as a “practical” as opposed to purely abstract or technical, “idea”; and, second, seek to protect and “promote” its “well-being,” rather than to merely exploit, “unmask or debunk it.” He argues that this juristic “promotion of a value-oriented idea of law,” which is “adapted to the specific, varying conditions of law’s sociohistorical existence is the most distinctive, perhaps ultimately the most difficult, form of legal expertise,”; and that it requires a distinctly sociological—as opposed to a black-letter law, or law and social theory—orientation.Footnote 10 For me, the unavoidable implication of Cotterell’s argument is that all socio-legal scholarship ought to be juristic. So how does such a juristic orientation translate into socio-legal practice?

First, a juristic orientation implies a focus on law as an empirical, real world, phenomenon. This aligns very easily with standard socio-legal practice which has for many decades, and thanks in large part to Max Weber, centered on systematic sociologically-informed studies of what I will call legal action—for example, of how police, judges, bureaucrats, activists, and/or litigants use, abuse, and avoid law. Second, a juristic orientation encourages the systematic, sociologically-informed study of “legal ideas”—for example, what are the core “values” present in law and society, where do they come from, and what are their effects? Again, this aligns with standard socio-legal practice, which in turn owes much to the work of Max Weber.

What makes a juristic orientation distinctive is that it can shed light on what legal values ought to be. This is controversial because sociology and, therefore, socio-legal scholarship, is traditionally directed to “understanding facts” rather than “applying values.”Footnote 11 Specifically, Cotterrell argues, a juristic orientation gives an overarching, normative purpose for socio-legal scholarship—namely, unity. Drawing on the work of German legal philosopher Gustav Radbruch (1878-1949), Cotterrell proposes that we conceptualize law as a “triangle” composed of “three central values.” Of these, two are basic technical values that fall within even the thinnest of conceptions of law: Namely order (“or security or certainty”) and justice (or “equal treatment”). But the third value, law’s “(fitness for) purpose,” is dynamic and contingent. Its “content”—including “who and what are to be considered equal … and how justice is to be measured and realised” is derived from, and so changes with, “sociohistorical place and time.”Footnote 12 The distinctive duty of the jurist who, by Cotterrell’s definition, seeks to promote the well-being of law as a practical idea, is to actively work to “hold” that “justice-order-purpose triangle of law together.” They must do this by conceptualizing law in ways that accommodate and promote diversity, specifically by “integrating as equally valuable subjects of law … all those living within the jurisdiction of a legal system.”Footnote 13 More specifically, the social function of law is to express the values and interests that hold us together, coordinate the differences that keep us apart, and encourage participation in social life.Footnote 14

The upshot for socio-legal researchers is that we have a juristic duty to promote social and legal unity from and for social and legal diversity. In my view, that duty applies to us both in our capacities as members of socio-legal research communities, and in relation to the impact that our research might have on communal networks beyond academia. At the heart of this duty is, I argue, a tension between unity/structure and diversity/freedom on the other:

On the one hand, a commitment to the well-being of law requires a commitment to “law’s unity” as a coherent “structure of values.” On the other hand, a commitment to law as a practical idea, one that is socially meaningful, requires a commitment to ensuring that it accommodates, and actively nurtures, diversity. Law achieves this objective, which Cotterrell terms “social unity,” by “facilitat[ing] communication” about the “need” for “respect” for “all”; as well as by enforcing that need by challenging inequality and bias.Footnote 15

This need to navigate the tension between structure and freedom, and this emphasis on law as a communicator, are clear points of contact between law and design. Furthermore, a juristic commitment to the well-being of law as a practical idea calls for skills, knowledge, and attitudes that are at once practical, critical, and imaginative; and, as will be seen below, this constitutes the third point of contact between law and design. What I did not fully appreciate before the opportunity presented by the workshop is that these points of contact exist in large part thanks to 19th and 20th Century Anglo-German efforts to organize design into a socially-attuned practice.

C. Design as Socially-Attuned Field of Practice

Generations of sociological thinking render it commonsensical for a socio-legal researcher to see law and design—and therefore, legal design—as fundamentally social phenomena—that is, “concerned with the mutual relations of human beings or classes of human beings,” especially with “society” and “its organization,”; and shaping and shaped by human “interdependence,” including the “need for companionship” and cooperation.Footnote 16 Perhaps more surprising to the socio-legal researcher, and indeed for some contemporary design enthusiasts, is that the discipline of design was, at its Anglo-German origins, remarkably socially-attuned. By this I mean that design was seen as a form of social relations, as playing a role in social relations, and as having a role to play in working for certain forms of social relations.

The story begins with the Arts and Crafts movement and its leading light, English designer and social activist William Morris (1834-1896). “Born of thinkers and practitioners in Victorian England who despaired of the ornate clutter which seemed to be pervading architecture and design,” this was a “movement about integrity. It was about respecting your materials, and the way you used them,” about “the maker and the process of making as much as the object made.” In so doing, it “produced works of extraordinary vibrancy and intellectual rigor.” Although the Arts and Crafts movement “came to an end shortly after the First World War,” its already global influence endured.Footnote 17 Crucial to that endurance was the fact that architect Walter Gropius was directly influenced by Morris in writing the Manifesto and Program for Germany’s famous Bauhaus school of art and design in 1919.Footnote 18

Although the Bauhaus itself was short-lived, its practices were secured in its curriculum and carried by its members as they scattered across the globe in the wake of its 1933 closure by the Gestapo. Much of the Bauhaus agenda was later picked up and extended at the Ulm School of Design (Hochschule für Gestaltung). From Ulm, “research into design methods crossed the channel and found its advocates in Britain” in “the ‘design methods movement’ of the 1960s,”Footnote 19 most visibly in the 1962 Conference on Design Methods in London. Designers have since periodically pushed back against the normative agenda of “design methodology.”Footnote 20 But the Bauhaus approach continues to exert global influence right through to the contemporary teaching and practice of design.

I. Design as Social Relations

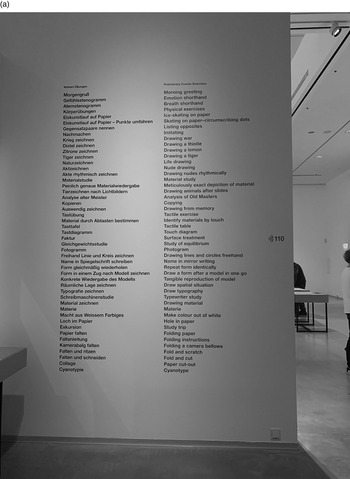

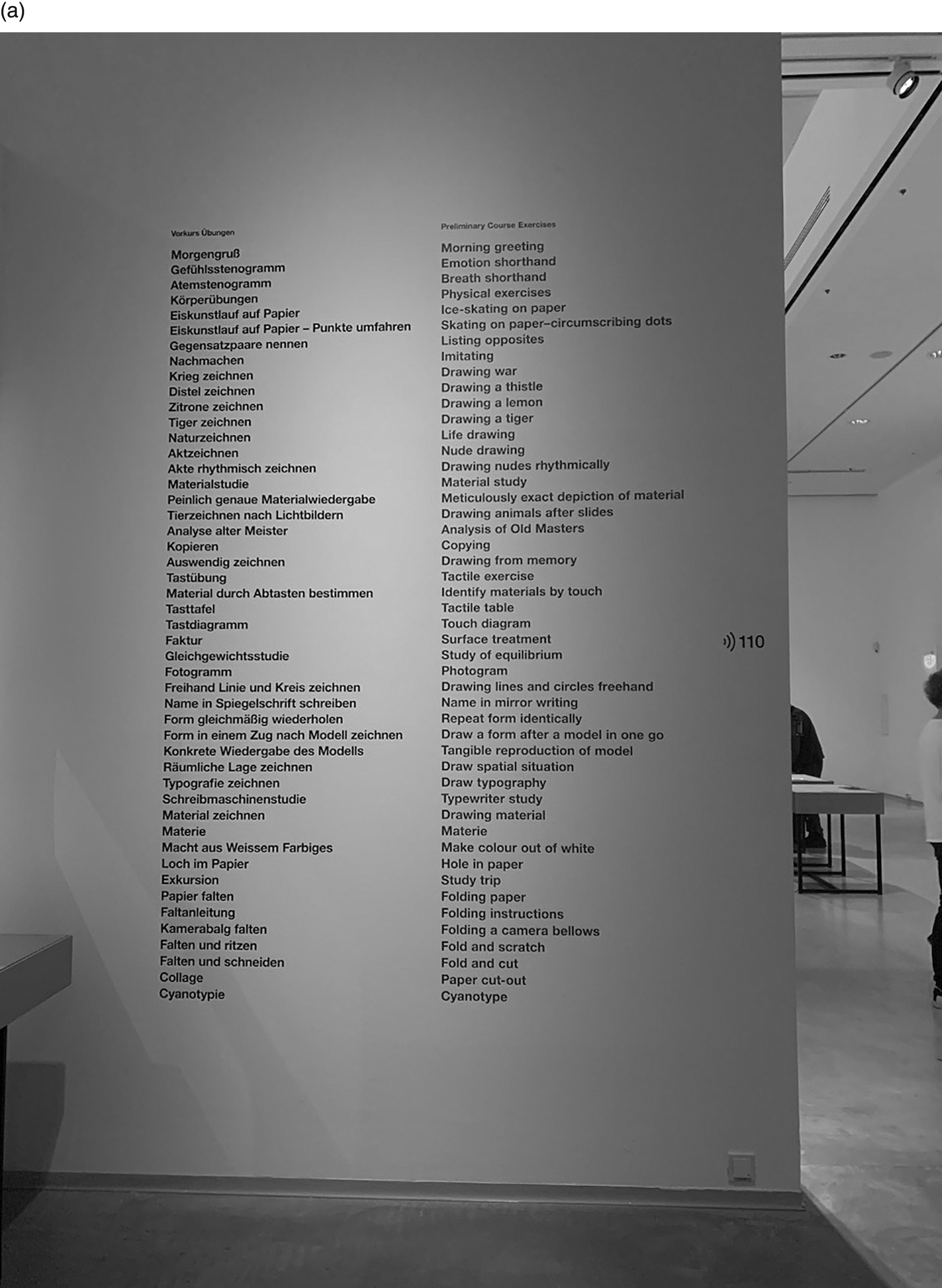

The Arts and Crafts movement and the Bauhaus school both demonstrated a keen awareness of, and willingness to exploit, the relational dimensions of design. The Bauhaus Preliminary Course (Vorkurs) was the first, at least in the global North, to systematize the teaching—and therefore practice—of design, and remains perhaps its most influential legacy.Footnote 21 The course “emulated Arts and Crafts practices,” not only in its “promotion of the applied arts and integrated design” but also in its communal “workshop-based system.”Footnote 22 Although “its character changed significantly” with each lead instructor—Johannes Itten, László Moholy-Nagy, and Josef Albers—it nevertheless “served as a unifying experience for students and a common ground from which all began their studies,” because all “students, be they joiner, bookbinder, potter, weaver or stage designer received the same instruction.”Footnote 23

More specifically, and in today’s terminology, we can say that they understood design as a form of sociomaterial relations. Course leaders at the Bauhaus echoed the Arts and Crafts movement’s determination that designers and users alike should fulfill their “psychological and sensory needs” by “the acts of creating, using, touching, and perceiving.”Footnote 24 For example, Johannes Itten saw experimentation as a way to “unlock students’ creative potential,” which he sought to do using “several unorthodox techniques, including rhythmic and improvisatory drawing,” “gymnastics,” and “other body-based, meditative” practices which were conducted communally. Under course leader Josef Albers, students were asked to complete a series of experiments—"practical, concrete exercises”—that emphasized “process” and “learning through doing”.Footnote 25

The outcomes of these regular experiments were brought together into a shared space and assessed. Although they were intended to function as mere drafts or prototypes, such examples still exist—even the names and specifications of the experiments—and are today, 100 years later, treated as artistic works and are exhibited in major art galleries around the world—either in their original state or reproduced in larger form. But it is rare to see them as they were intended—as a collection of experiments on a common theme that generated a sense of community.Footnote 26 Figure 4).

Figure 3. Assessment of work from Albers’s Preliminary Course, 1928-1929.

Figure 4. Vorkurs exercises celebrated (a) as a list and (b) in large scale, high quality reproduction.

II. Design in and for Social Relations

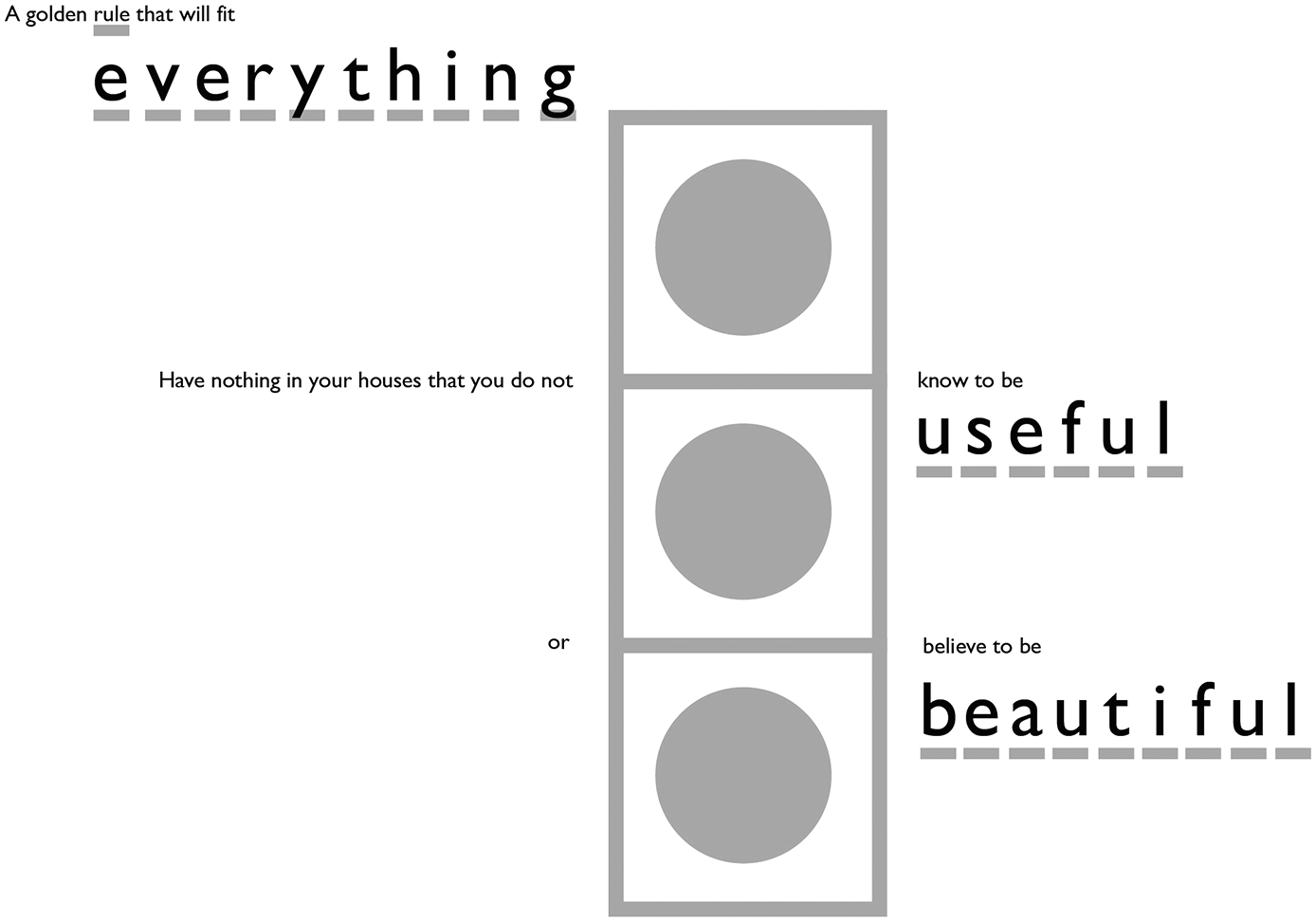

Members of the Arts and Crafts movement and the Bauhaus understood design(s) normatively, as tools for shaping social relations. They pursued a—then radical—agenda of making design relevant, appealing, affordable, and even transformative to all, including the relatively poor. For example, Morris asked in 1883, “[w]hat business have we with art at all unless all can share it?”Footnote 27 Likewise, “[u]niting all of [the Bauhaus’] multiple tendencies and impulses was an attempt to put art and architecture to use as social regeneration for the world’s working classes.” But it took some time to get there: Gropius originally wrote in his 1919 manifesto that “[t]he ultimate aim of all artistic activity is building!” and “[t]he ultimate, if distant, aim of the Bauhaus is the unified work of art.” But in 1929 thendirector of the Bauhaus, Hannes Meyer, “consciously revised the statement, in poetic form, no less: ‘thus the ultimate aim of all Bauhaus work/the summation of all life-forming forces/to the harmonious arrangement of our society.’”Footnote 28 Relatedly, both the Arts and Crafts movement and the Bauhaus were committed to the practical idea that, above all, designs must function. For example, Morris exhorted his followers to “have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful”Footnote 29 (See Figure 5)— a sentiment since summarized in the maxim “form follows function,” which is widely associated with the Bauhaus.Footnote 30

Figure 5. William Morris’ 1880 exhortation for useful, beautiful design.

Over time it became clear that this socially-attuned quest for user-centered functionality ought to begin further upstream, with design theory and pedagogy. So, at the Ulm school of design, Bauhaus graduate Max Bill sought “to make the design process more readily accessible and easy to understand,” and thereby “to facilitate cross-disciplinary work, for example with anthropology and psychology.”Footnote 31

Thereafter, as design was evermore associated with consumerism, designers across the world have pushed back with regular attempts to highlight its ever-present political dimensions. Perhaps most famously, in 1964, UK-based designer Ken Garland launched First Things First, a rather Arts and Craft-y/Bauhaus-y “manifesto,” calling on designers to take more responsibility for their practice. It was restated in broader terms in 2000 and 2014, and now calls to address “environmental, social and cultural crises.”Footnote 32

In recent years, design has come to be applied—across a wide range of private, public, and civil society contexts—to create or enhance not only “physical products” but also “services, strategies and policies.”Footnote 33 This movement towards what is often referred to by the—misleadingly partial—moniker of “design thinking”Footnote 34 has been especially pronounced in countries such as the UK and Germany that are home to well-developed design sectors. For example, globally, Germany and the UK ranked 4th and 5th respectively for their per capita design-related exports in 2015. While the UK “has the largest design sector” in Europe and its government was “one of the first to recognise the power of design” in the private and public policy sectors,Footnote 35 the Policy Lab of the German Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs uses “design thinking labs” to promote “cooperative thinking.”Footnote 36 Anglo-German influence over design thinking discourse is to be found in an ever-growing collection of frameworksFootnote 37—variously described as systems, toolkits, guides, and so on. For example, the Design Council—which is an independent charity and adviser to the UK Government on design—produced in 2004 a globally influential Double Diamond, visualizing four phases in design processes: Discover, define, develop, and deliver.Footnote 38 Likewise, a largely German team of independent designers was behind the globally influential This is Service Design Thinking project, which centers on three designerly tools: Personas, maps, and prototypes.Footnote 39

Proponents of “design thinking” see it as “a cognitive style” that can serve as a “resource for organizations.”Footnote 40 However, as the pioneers of the Arts and Crafts movement and the Bauhaus always already knew, design is much more than a way of thinking. It is a sociomaterial practice—that is, a “routinized . . . behavior” including bodily and mental activities, “‘things’ and their use,” “background knowledge,” know-how, emotion, and motivation. Seen as a practice, “design thinking” comprises not merely the thoughts and actions of individuals, but rather “dynamic configurations of minds, bodies, objects, discourses, knowledge, structures/processes and agency.”Footnote 41 So it makes more sense to think in terms of sociomaterial “designerly ways.”Footnote 42

Since at least 2001, there has been an increasingly concerted and global effort to apply design—more often “design thinking” than “designerly ways”—in the legal sphere.Footnote 43 Initially, the focus was on visualizing legal instruments such as contracts,Footnote 44 while recent efforts have addressed more strategic and systemic concerns.Footnote 45 As I have argued elsewhere, the rise of what we now call “legal design”Footnote 46 can be both explained and justified by the existence of important “points of contact” between “lawyerly concerns” and “designerly ways.” On the one hand, drawing on Roger Cotterrell, I argue that lawyers need to communicate; they need to balance structure/unity and freedom/diversity; and they need to be at once practical, critical, and imaginative. On the other hand, drawing on social designer Ezio Manzini, I argue that designerly ways—especially the emphasis on communication, experimentation, and making things visible and tangible—can improve communication and generate new spaces of “structured freedom,” in which lawyers can be simultaneously practical, critical, and imaginative.Footnote 47 Given these synergies, I have argued that attention ought also to be paid to the potential of design to enhance legal, especially socio-legal, research.

D. Designerly Ways for socio-legal Community?

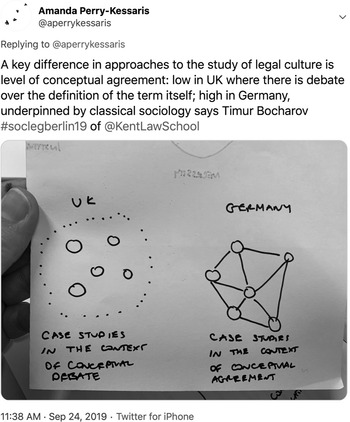

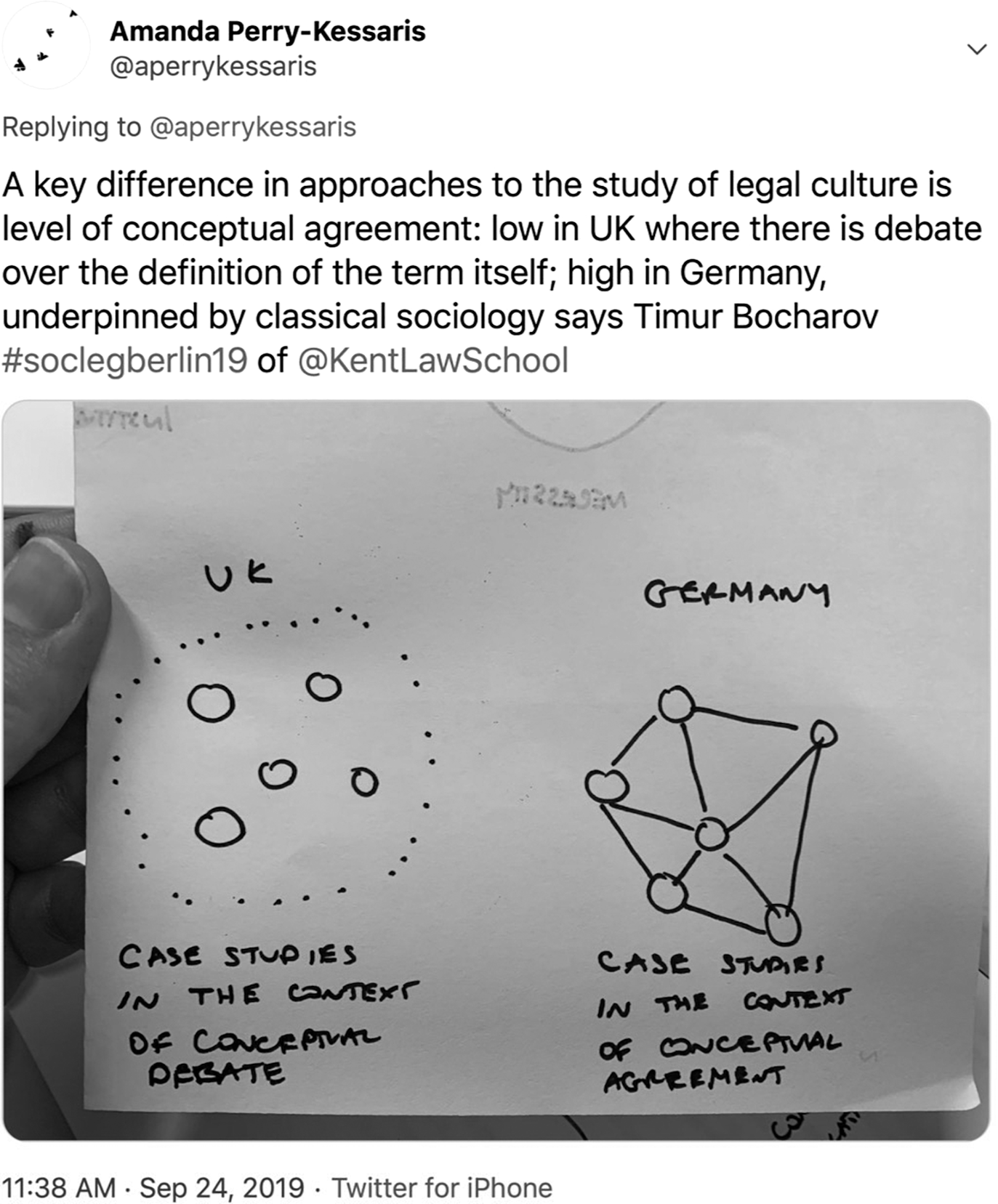

A key insight emerging from my research into the potential of design to help us understand and enhance socio-legal research methodology is that designerly ways can help us more productively to navigate the tension between structure and freedom that is inherent in socio-legal research. That tension manifests not only in law’s (in)ability to promote social unity from and for diversity, but also in scholarly (in)ability to promote conceptual unity from and for diversity and, relatedly, the (in)ability of academic communities to promote social unity from and for diversity among their members. For example, in his presentation at the Berlin workshop underpinning this Special Issue, Timur Bocharov explored one specific difference between the two jurisdictions (Figure 6)—namely, a lack of conceptual agreement around “legal culture” in socio-legal scholarship coming from the UK; and, in stark contrast, a clear consensus among German scholars around the concept of “Recht als Kultur”—that is, founded in the home-grown classical sociology of Max Weber and Georg Simmel.Footnote 48 And this divergence may be symptomatic of the fact, as noted above, that German socio-legal culture is perceived to be relatively structured and UK socio-legal culture is perceived to be relatively free. What might be the impact of any difference in general aversion/adherence to canon, or in divergence in the content of said canon, on the possibility of future Anglo-German collaboration on socio-legal research? And might it be overcome with the aid of design?

Figure 6. Live-tweeted visual summary of presentation by Timur Bocharov on “Legal Culture v. Recht als Kultur: the UK and German Approaches to Law and Culture” at “Socio-Legal Studies in Germany and the UK: Theory and Methods”.

I. Socio-Legal Model-Making

Multiple sub-fields, such as transition design and social innovation design, have seen designers collaborating with communities through design for more or less radical social change.Footnote 49 For example, social innovation designers provoke and facilitate us—“diffuse designers”—to work collaboratively for social change by approaching our own field of expertise or life in “design mode.”Footnote 50 Here, the intended users of the social design output—which may be, for example, an artifact, environment, service, or event—become “coresearchers and co-designers exploring and defining the issue, and generating and prototyping ideas.”Footnote 51

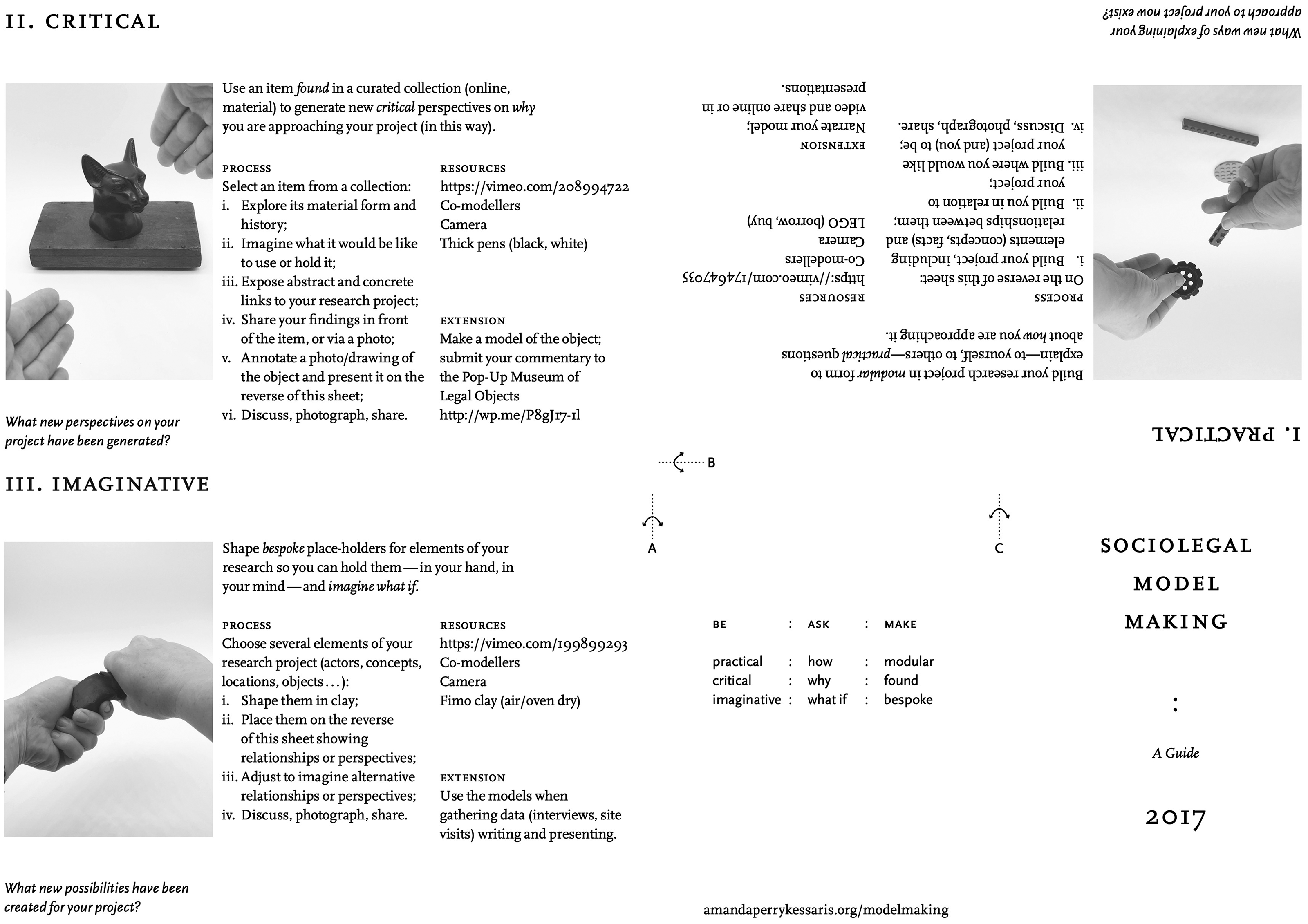

Between 2016–2017, I drew on these practices to run a series of experiments in the UK that eventually included around 100 researchers and focused on how we might make socio-legal ideas “visible and tangible,” and how that might affect the social dimensions of socio-legal research. Participant researchers engaged in individual and collaborative model-making in relation to their ongoing projects. The primary outcome of those experiments was an openaccess guide introducing three forms of socio-legal model-making (See infra Figure 7): ‘Modular” model-making, in which systems such as LEGO are used primarily for the practical purpose of explaining; “found” model-making, in which stumbled-upon or curated items are used primarily for the critical purpose of generating new perspectives; and “bespoke” modelmaking, in which artifacts are made—for example—from clay, primarily for the imaginative purpose of speculating about new possibilities.Footnote 52

Figure 7. A guide to socio-legal model-making, designed to be downloaded and folded into a booklet.

The most potentially significant of these instances of socio-legal modelmaking occurred during the compulsory postgraduate Research Methods in Law module at Kent Law School, which became distinctly more social and more communal as a result. The module runs for autumn and spring terms. A model-making session is held towards the end of the first term. The session is based around an A3 landscape printed worksheet on which participants from all over the world are asked to use a LEGO set to complete three builds relating to their research projectFootnote 53: First, they build a representation of their project, focusing on key concepts, actors, and relationships; second, they add in a representation of themselves in relation to the representation of the project; third, they build a representation of what they hope their project will be in the future. More experienced student researchers attend the session to act as mentors. Participants are encouraged to video or photograph the process throughout to remind themselves of how their build progressed; to explain their model to other participants, especially mentors; to ask each other questions about the models of others, and to offer critical feedback. Feedback reveals that model-making not only helps participants to better understand their research but also reminds them of the need to “discuss our projects more, to learn more from each other.” They provoked and facilitated to form trusting relationships with each other, and to engage in depth with each other’s projects; and these relationships extend beyond their cohort. A sociomaterial community of practice is formed (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Postgraduate research students modelling their projects at Kent Law School.

It is particularly gratifying—and relevant to the present context—that students, such as Steve Crawford, have transferred socio-legal design skills learned at Kent Law School to other postgraduate and faculty in the UK and elsewhere in Europe,Footnote 54 including to postgraduate researchers Lisa Hahn and Siddharth de Souza, who have in turn introduced it to the postgraduate research community at Humboldt University in Berlin via their vibrant socio-legal Lab, on which more below.

II. Making Anglo-German socio-legal Research Community?

The question that arises then is whether designerly ways might be especially well-suited to facilitating Anglo-German cooperation around socio-legal research. Visual summaries of the kind that I live-tweeted during the workshopFootnote 55 (See infra Figures 1, 6) are one simple example. But what if, for example, by collaboratively making our ideas visible and tangible—in material models or even virtually—we might generate a sense of community among UK and German socio-legal researchers?

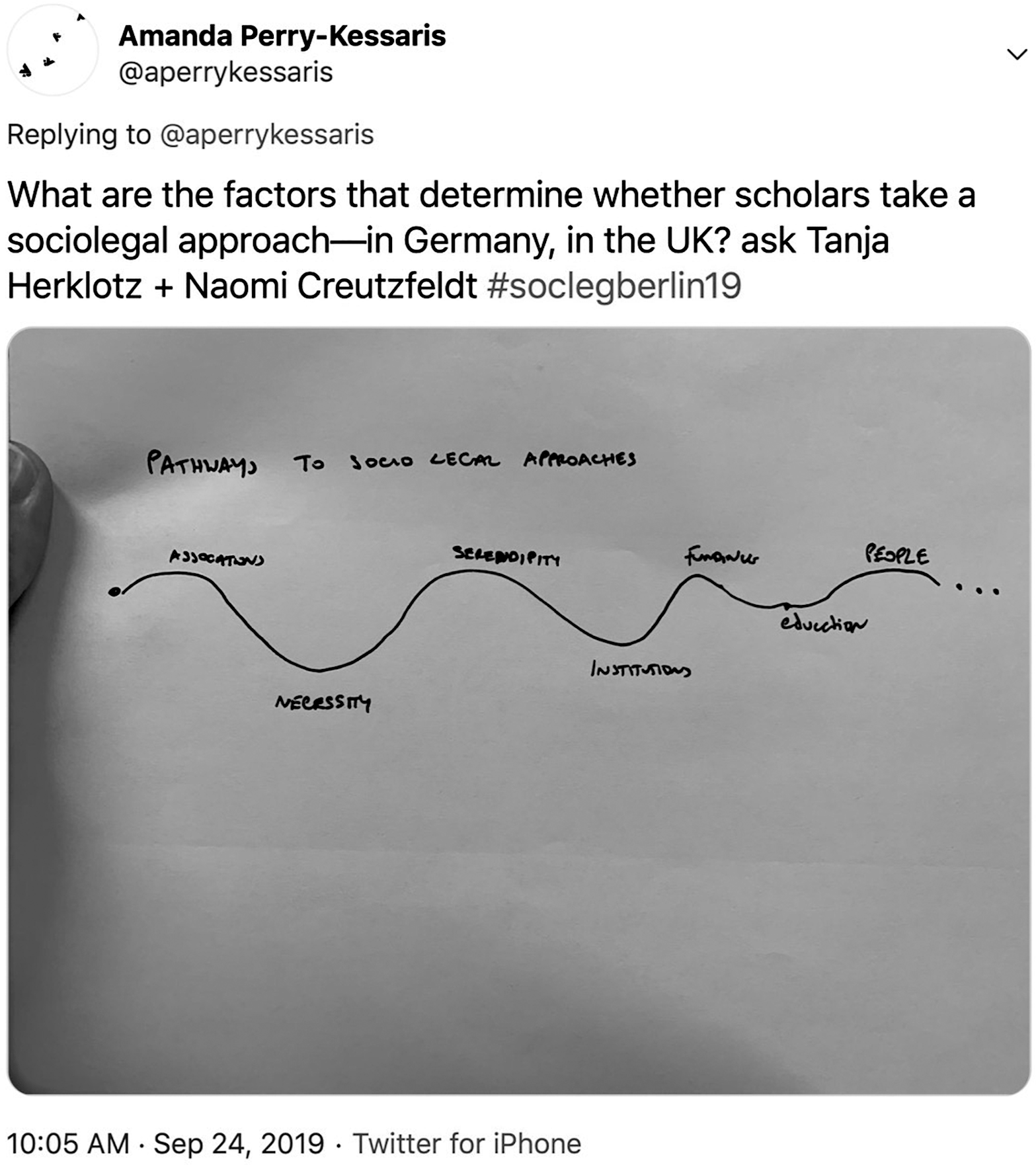

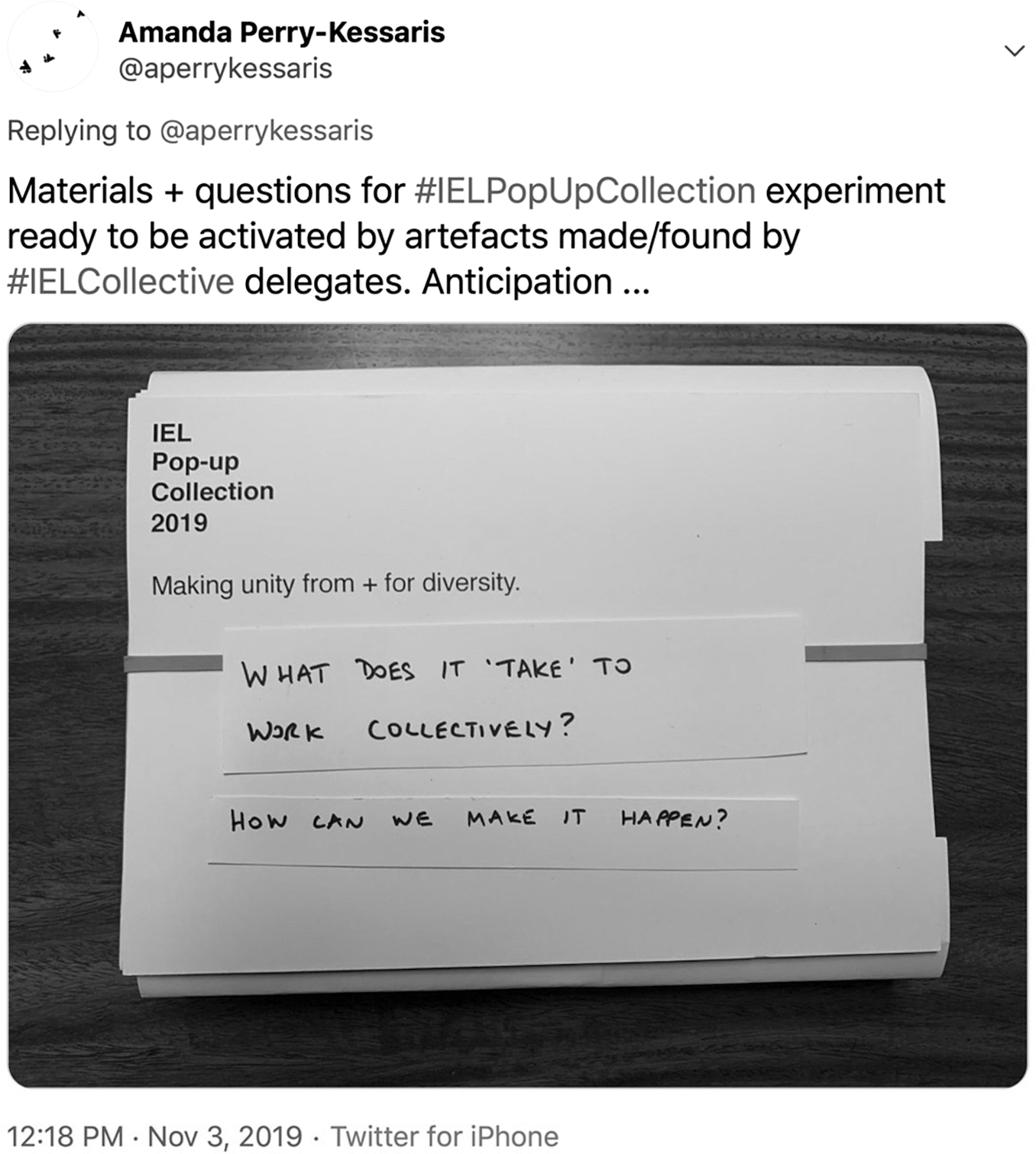

For a transnational precedent, we can look to the inaugural conference of “The IEL Collective”—a collaboration of academics and practitioners from across the world who aim to work inclusively to “stimulate conversations about plurality, representation and criticality”—in the field of International Economic Law.Footnote 56 Like any possible future effort at promoting Anglo-German socio-legal community, the Collective can be framed as a “prefigurative” endeavor, in the sense that its participants seek to “perform present-day life in the terms that are wished-for,” both in order “to experience a better” present, and “to advance” future change”.Footnote 57 Returning to the normative agenda outlined above, we can see that for the IEL Collective collaboratively to protect and promote the “wellbeing” of international economic law as a “practical idea” requires unified-yet-diverse thinking. It is only by bringing diverse conceptual frames, empirical examples, and normative agendas into the same space that we can really respect, understand, and use them in practical, critical, and imaginative ways. Collaborative mindsets, tools, and processes are not part of traditional legal scholarship and practice. Might they be introduced though model-making? This was the question that motivated me to propose the co-production of an IEL PopUp Collection as part of the IEL Collective inaugural conference held at Warwick Law School in November 2019.Footnote 58

The Pop-Up Collection was designed to make unity from and for diversity, visibly and tangibly, and in prefigurative spirit. Delegates from across the world were invited to bring with them to the conference an artifact (object or image) that they felt was relevant to their approach to, or understanding of, International Economic Law, that was either found or made, and that would fit on an A5 page. Most delegates had never met, and were unlikely to have engaged in such an activity in the past, but these barriers to engagement were offset by the context—that is, the warm, inclusive, and non-hierarchical approach of the people at the heart of the Collective; and via specific social media prompts (Figure 9). During the conference, the artifacts were placed on designed A5 cards in the form of a grid. Arrows printed on the cards indicated possible points of contact or influence between the artifacts, and the approaches to or understandings of IEL that delegates intended them to represent. For example, Figure 10 shows delegates handling and discussing an artifact, made by Gamze Erdem Turkelli, to represent International Economic Law as a black box. On opening, we find plain notes representing the international economic activities—trade, investment, and aid—and elaborate bejeweled notes representing the promised benefits of engaging in such activities—for example, prosperity. Eventually, we realize that the box contains another hidden layer full of decentered concerns, such as climate change, colonialism, and gender. The Collection grew, shrank, grew again, and moved to a new venue over the course of the two days—a quiet, shifting presence. The impact of the Collection, and of the event, was extended through video tweets of such discussions.Footnote 59 This experiment was successful in generating a “structured-yet-free” prefigurative space for practical, critical, and imaginative thinking—both individual and collective. That space was necessarily limited by the usual constraints of time and attention, all the more so in the context of the heady and transformative atmosphere of the wider IEL Collective conference. But it is there to be reactivated at future events, and deepened via an online collection of commentaries.Footnote 60

Figure 9. IEL Pop-Up Collection display cards as social media prompt.

Figure 10. Delegates interacting with models at the IEL Collective inaugural conference in Warwick.

What evidence is there that it might be possible and productive to conduct an Anglo-German socio-legal Studies variant of this experiment? One reason for hope is the Socio-Legal Lab at Humboldt, which seeks:

[T]o create an environment that facilitates collaboration in research, to provide a communication space that is open and safe for wide-ranging discussions, and to create communities of support for researchers such that they feel empowered to voice their anxieties and to test and incubate new ideas.Footnote 61

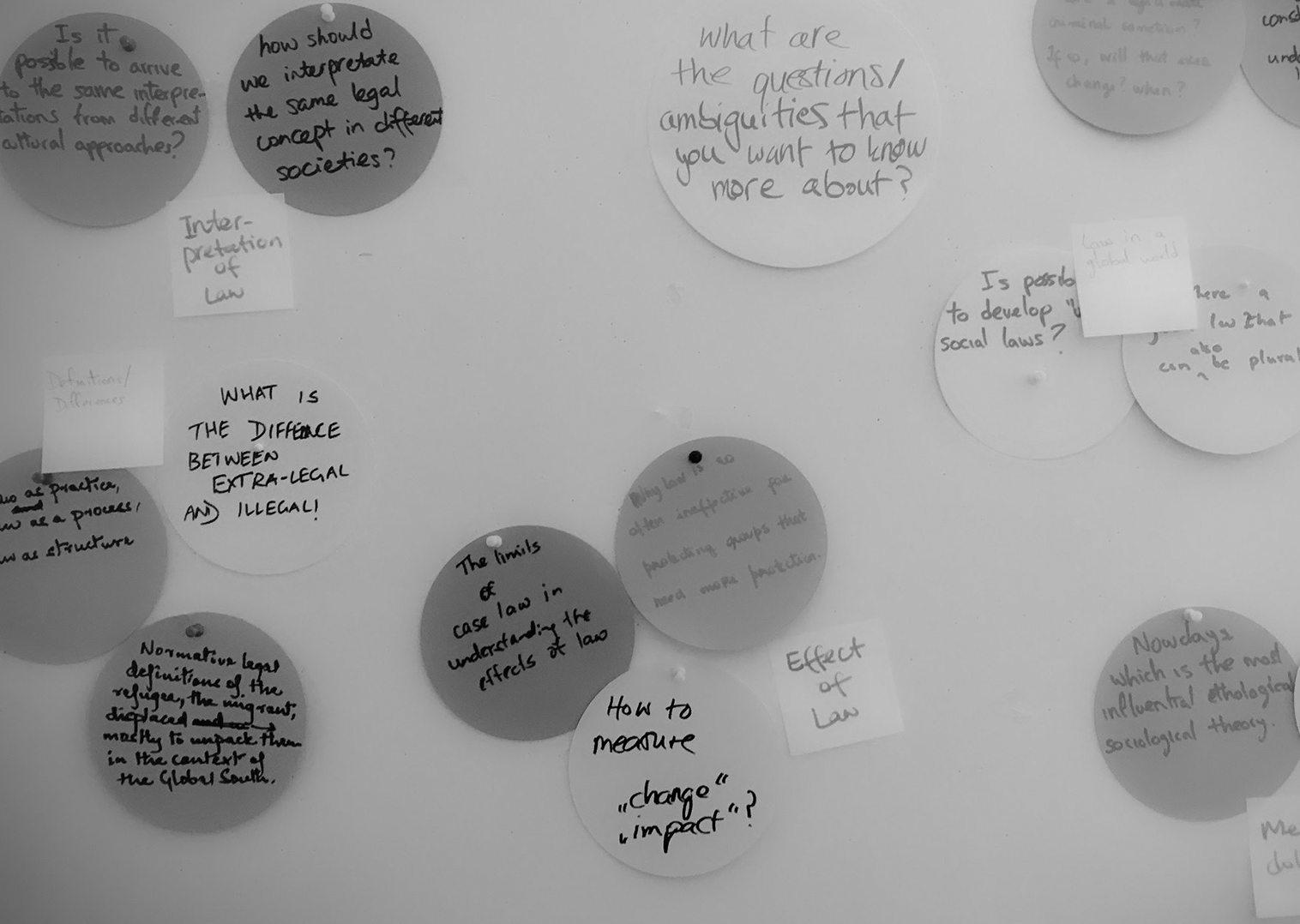

It can be seen as designerly, in the sense that it promotes experimentation—both with different methods and with “different ways of communicating research,” including visualization (See Figure 11)—to determine “what works best in conversation and cooperation with others.” Although it is explicitly disruptive in orientation, it has been supported by institutions—such as the Law and Society Institute Berlin and the Berliner Arbeitskreis Rechtswirklichkeit (Berlin Working Group on socio-legal Studies, BAR)—and attracted participants from across Germany.Footnote 62 So it is safe to predict that at least some of its innovations will be absorbed into the German mainstream.

Figure 11. Brainstorming the interrelations between law and society.

Lest we forget, the UK and Germany share darker histories too, not least a propensity for empire-building. Much remains to be done in both jurisdictions to face the past, present, and future effects of those histories. For example, Philipp Dann has observed a “contemporary amnesia,” both regarding the pursuit by the German state of empire outside Europe (18751919) and within Europe (19391945), and regarding East and West German scholarly critiques of empire-building by the “other side” during the Cold War.Footnote 63 This shared imperial history is relevant here because mainstream visions of design are—like law—infused with a particular social and political history. Design began to emerge as “an aspect of every day” during the Industrial Revolution because mechanization focused attention on making, and because European societies became “pervaded by expert knowledge and discourses.” Over time, Eurocentric conceptions of design were exported, not least via empire, as part and parcel of the “universalizing ontology of dominant forms of modernity.” So, argues Arturo Escobar, if design is to play a role in meaningful social change—especially in non-European and postcolonial contexts—it must first “be creatively reappropriated.”Footnote 64 Any proposal to use designerly ways to promote Anglo-German socio-legal community must be open—proactively inclusive of all, especially those stakeholders whose perceptions, expectations, and experiences might otherwise be ignored.

E. Conclusion

My initial workshop preparation strategy was to look for signs of Anglo-German life in my niche field of study. This led me to questions that I would never otherwise have considered, and to answers that are both surprising and reassuring to me as a UK-based transnationalist in Brexity times. In particular, design communities in the UK and Germany can both lay substantial and roughly equal claims to establishing design as a socially-attuned discipline; and while I have since been initiating the systematic exploration of design’s potential for socio-legal research, early career researchers have been early adopters and innovators in Germany. Long may this story of mutual Anglo-German provocation and appreciation continue.

The combined effect of Anglo-German scholarship and practice is to teach us that a “sociological imagination”Footnote 65 is essential if we are to fully understand possible synergies between design and socio-legal research, and the risks and rewards of activating them. At the time of writing, social relations of all kinds are being strained, broken, deepened, and reinvented to accommodate the material threats posed by a global pandemic; all on the back of sustained pressure relations, perhaps especially Anglo-German relations, arising from Brexit; and all in the context of the rise of other nationalistic movements across the world. We cannot know what socio-legal research will or ought to look like in the coming months and years. My own experience of pandemic-lockdowns-as-natural-experiment has made visible to me how important sociomaterial interaction with my socio-legal community is, and reinforced my conviction that we must pay more attention to designing those moments that we are lucky enough to share in person.