Introduction

Globally, public participation has become a defining feature of contemporary constitution-making processes. Comparative studies highlight an increasing trend toward involving citizens not only in the ratification of constitutional texts but also during earlier stages of drafting and deliberation (Corvalán and Soto Reference Corvalán and Soto2021; Hudson Reference Hudson2021; Hirschl and Hudson Reference Hirschl and Hudson2024). Some scholars argue that the participatory process itself can be as significant as the resulting constitutional text – if not more so – warranting critical reflection on its meaning and impact across different contexts (Ghai and Galli Reference Ghai and Galli2006). Citizen involvement is frequently associated with enhancing constitutional legitimacy, promoting civic education and fostering a shared political identity – factors that are crucial for consolidating new democratic orders, especially in post-conflict or deeply divided societies (Choudhry and Tushnet Reference Choudhry and Tushnet2020). Participation may also strengthen civic competence and institutional trust, increasing citizens’ long-term engagement with democratic institutions (Eisenstadt et al. Reference Eisenstadt, LeVan and Maboudi2017).

Yet, citizen participation in the making of new constitutions has taken multiple forms. Historically, involvement was often limited to electing representatives to constituent assemblies or voting in referendums on final texts. Over time, however, more comprehensive and sustained mechanisms of engagement have emerged (Widner Reference Widner2008; Saunders Reference Saunders2012). South Africa’s constitution-making process (1994–1996) is widely recognized as a landmark example. Through an extensive public outreach program – including civic education campaigns, public meetings, hearings and written submissions – the Constitutional Assembly received over two million citizen inputs that informed the drafting of the 1996 Constitution (Ebrahim Reference Ebrahim1998; Hudson Reference Hudson2021). Similar practices were developed in Colombia (1991), where citizens contributed proposals through Regional Working Groups and Preparatory Commissions. Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) also played an active role during the National Constituent Assembly’s deliberations (Rojas Betancur et al. Reference Rojas Betancur, Arbeláez, Yepes and Molina2019). Ecuador’s Constituent Assembly (2007–2008) established a dedicated ‘citizen participation unit’ to review more than 1,600 proposals gathered through public forums, territorial tables and social movements, some of which were incorporated into the final text (Beler Novik, Reference Beler Novik2018). Bolivia’s Constituent Assembly (2006–2009) employed public hearings to incorporate local perspectives into constitutional deliberations (Gamboa Rocabado Reference Gamboa Rocabado2009).

In addition to these face-to-face methods, recent constitution-making processes have leveraged digital platforms to expand access and engagement. Iceland’s (2010–2013) Constitutional Council pioneered the use of ‘crowdsourcing’ by publishing draft versions online and inviting citizen feedback through social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter. While participation was modest – about 3,600 submissions from a population of 320,000 – the process demonstrated the potential for digital public engagement in constitution drafting (Landemore Reference Landemore2020b). Egypt’s 2012 process introduced an official online platform for citizens to review drafts, submit suggestions and cast votes, ultimately receiving over 650,000 comments from more than 68,000 participants, despite a polarized political context (Maboudi and Nadi Reference Maboudi and Nadi2016). Tunisia’s National Constituent Assembly (2011–2014) combined traditional consultations with an online platform following the release of its second draft. However, public engagement was limited, and the process was criticized for insufficient promotion of participatory opportunities (Carter Center 2014).

Earlier institutionalized forms of public input can be found in Brazil and Poland. Brazil’s 1988 National Constituent Assembly developed a robust participatory framework by integrating citizen petitions and popular amendments, backed by millions of signatures, into its formal legislative process (Rauschenbach Reference Rauschenbach2011; Mendes Cardoso Reference Mendes Cardoso2016; Welp and Soto Reference Welp and Soto2019). Poland’s 1997 constitutional process allowed ‘popular drafts’ to be submitted, provided they had at least 500,000 signatures. This mechanism enabled civil society and opposition groups to formally contribute to constitutional debates, although institutional resistance ultimately constrained their influence on the final text (Garlicki and Garlicka Reference Garlicki, Garlicka and Miller2010).

Despite endorsements from international organizations such as the United Nations and IDEA, there remains limited empirical evidence on the substantive impact of participatory mechanisms in constitution-making (Ginsburg, Elkins and Blount Reference Ginsburg, Elkins and Blount2009; Parlett Reference Partlett2012; Saati Reference Saati2015). Against this background, Chile’s recent constitution-making process (2021–2023) offers a valuable case for examining both the opportunities and limitations of participatory constitution-making in practice. The recent Chilean experience is particularly notable for the development of one of the most institutionalized mechanisms for citizen participation: the Citizen Initiative (CI). While this tool is commonly associated with legislative processes in other countries – allowing citizens to propose or influence the drafting of laws – Chile became the first country to incorporate a CI mechanism as a deliberative input tool within the formal process of drafting a new constitution, rather than as an amendment mechanism to an existing one. This innovation differs significantly from traditional CIs, such as Switzerland’s federal popular initiative – established in 1891 – which enables constitutional amendments through referendums within an existing constitutional framework. In contrast, Chile’s mechanism was embedded in the constituent process itself, granting citizen proposals institutional parity with those of elected representatives, without triggering a referendum or direct vote. This represents a distinct and significant expansion of participatory constitution-making.

A significant body of scholarship has critically analyzed the design and limitations of the recent Chilean constitution-making processes (Canzano Giansante et al. Reference Canzano Giansante2023; Issacharoff and Verdugo Reference Issacharoff and Verdugo2023; Ginsburg and Álvarez Reference Ginsburg and Álvarez2024; Landau and Dixon Reference Landau and Dixon2024; Suárez Delucchi Reference Suárez Delucchi2024; Toro Maureira and Noguera Larraín Reference Toro Maureira and Noguera Larraín2024). These studies have primarily focused on institutional design features – such as fragmentation within the Constitutional Convention, lack of party leadership and overrepresentation of certain activist agendas – which they identify as key factors contributing to the failure of ratification. However, none of these works provides a detailed account of the regulation and performance of CIs in either of the two constitution-making processes. This article complements existing analyses by addressing this gap, offering the first comprehensive examination of how CI were regulated, how they operated in practice and what their outcomes reveal about their potential for institutional continuity in future participatory mechanisms.

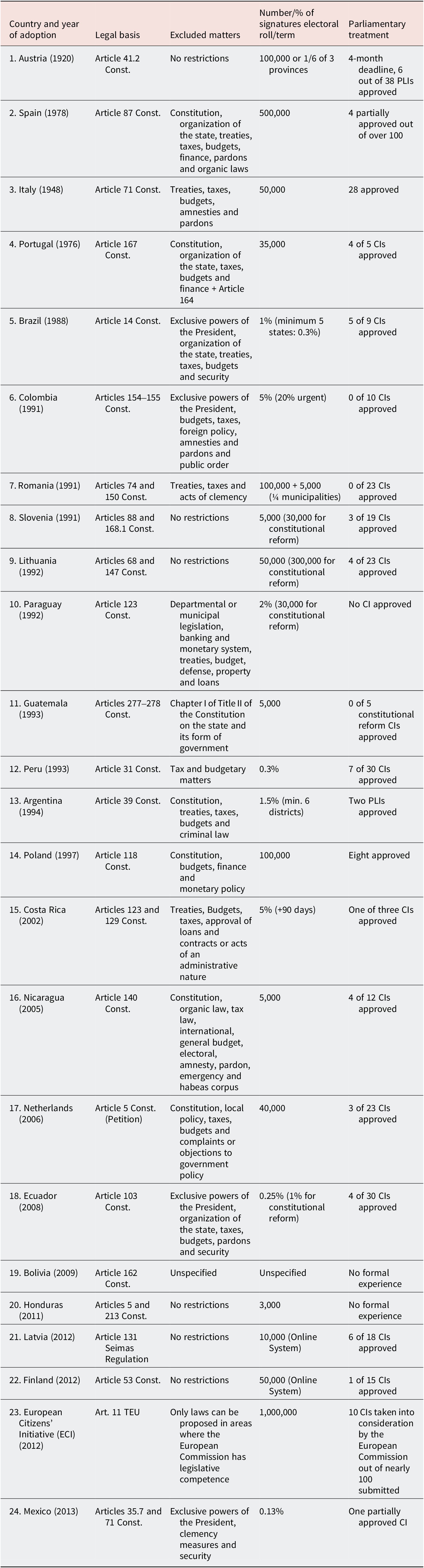

As noted, CIs have traditionally been associated with legislative processes rather than constitution-making. Historically, this mechanism – which enables a segment of the electorate to formally propose legislative changes – was first institutionalized in the 1920 Austrian Constitution. Hans Kelsen, its original author, regarded the CI as a fundamental instrument of democratic participation. By allowing citizens to collectively influence the formation of the state’s will, Kelsen argued, CIs fostered deliberative dialogue, transforming general public concerns into legislative proposals that parliaments were obligated to consider (Kelsen Reference Kelsen1932, Reference Kelsen2008). In this article, we adopt a concept of the CI aligned with contemporary theorists such as Devra Moehler and Hélène Landemore, who underscore its potential to enhance democratic responsiveness and address systemic deficiencies in representative systems. Moehler (Reference Moehler2008) contends that CIs can empower a more informed and engaged citizenry, capable of holding political leaders accountable and advancing public priorities in areas often neglected by traditional legislative bodies. Landemore (Reference Landemore2020a) further develops this perspective, situating CIs within an ‘open’ model of democracy that complements representative institutions. She emphasizes their remedial role in addressing legislative blind spots, providing citizens with institutional pathways to introduce proposals that might otherwise be marginalized (Landemore Reference Landemore2020a: 75). Moreover, Landemore highlights the capacity of CIs to empower motivated minorities to contest majoritarian decisions or injustices, thereby compelling legislators – whether randomly selected or traditionally elected – to anticipate and respond to potential challenges from an engaged public (Landemore Reference Landemore2020a: 203–204).

This article analyzes the use of the CI (Iniciativas Populares de Norma) in Chile’s two recent constitution-making processes spanning 2021–2023. More than one million citizens participated through digital platforms, submitting and endorsing proposals that were integrated into formal constitutional deliberations. While the CI is an established mechanism for public participation in legislative processes across Europe and Latin America, its use in constitution-making remains rare. Chile’s case reflects a broader phenomenon often described as constitutional borrowing, transplantation or the migration of constitutional ideas (Epstein and Knight Reference Epstein and Knight2003; Choudhry Reference Choudhry2007; Perju Reference Perju, Rosenfeld and Sajó2012).

Traditionally, CIs are legally regulated instruments that allow citizens to propose new laws, amendments or policies directly to legislative bodies, typically after gathering a requisite number of supporting signatures. These mechanisms are generally categorized as either ‘weak’ CIs (or Agenda Initiatives), requiring parliamentary consideration, or ‘strong’ CIs, which can directly trigger referendums, as seen in Switzerland or Uruguay. As shown in Table A1, since first being regulated in Austria’s 1920 Constitution and advocated by Kelsen, the CI has spread across multiple jurisdictions, including Portugal (1976), Spain (1978), Brazil (1988), Colombia (1991), Romania (1991), Slovenia (1991) and Poland (1997). More recent examples include Costa Rica (2002), the Netherlands (2006), Ecuador (2008), Bolivia (2008) and Finland (2012), with Mexico adding a CI mechanism in 2013 (Suárez Antón Reference Suárez Antón2019). At the supranational level, the European Citizens’ Initiative (ECI), established under the Lisbon Treaty in 2012, allows European Union (EU) citizens to propose legislative initiatives for consideration by the European Commission. Despite its promise, the ECI faces structural limitations: few initiatives achieve the required one million signatures, and the Commission retains full discretion over advancing proposals to the European Parliament (Suárez Antón Reference Suárez Antón2020).

Complementing the ECI, the Conference on the Future of Europe (CoFoE) introduced an ambitious participatory framework combining transnational citizen panels, a multilingual digital platform and plenary sessions that produced recommendations on EU policy and governance, including issues of constitutional relevance (Geuens Reference Geuens2023: 149–168). However, CoFoE’s outputs were consultative, lacking binding mechanisms for integrating recommendations into EU legislative or constitutional processes (European Parliament 2022; Geuens Reference Geuens2023: 154–155). As Jančić (Reference Jančić and Jančić2023: 3–30) notes, these mechanisms reflect the EU’s gradual institutionalization of citizens as public law actors but remain complementary to representative democracy rather than conferring direct decision-making power. Similar developments at the national level, such as Ireland’s Constitutional Convention (2012–2014) and Citizens’ Assembly (2016–2018), demonstrate increasing openness to citizen participation in constitutional reform debates, although citizen proposals remained nonbinding, with governments retaining discretion over their adoption (Doyle and Walsh Reference Doyle and Walsh2020: 453). Even Switzerland, often considered a model of direct democracy (Cronin Reference Cronin1989; Kriesi Reference Kriesi2008), has primarily used CIs to propose constitutional amendments within an existing legal framework – culminating in referendums – but not as a mechanism embedded in a foundational constituent process. In that sense, while over 200 federal initiatives have been proposed since 1891, only a small fraction resulted in constitutional amendments, and none were part of drafting an entirely new constitution (Swiss Confederation 2025). Chile’s CI, by contrast, functioned within a process of replacing the constitutional order, offering nonbinding yet formally regulated citizen input to constituent bodies – a feature not present in the Swiss model.

Against this backdrop, Chile’s recent experience with the CI during its constitution-making processes (2021–2023) stands out as an unprecedented application of this participatory tool in constitutional design. Unlike the ECI or the CoFoE, which focus on consultative input and agenda-setting within representative frameworks, Chile’s CIs were structurally integrated into the formal constitutional drafting procedures. Citizen proposals meeting procedural thresholds were granted institutional parity with proposals introduced by elected representatives. A significant number of Chileans actively engaged in submitting and endorsing initiatives, facilitated by digital platforms that streamlined participation and broadened accessibility.

This institutional design allowed citizens to directly shape constitutional debates, positioning them as co-authors of the proposed texts rather than mere consultees. Although both constitutional drafts produced during these processes were ultimately rejected in national referendums, the Chilean CI represents a qualitative advancement in participatory democracy, combining digital innovation with formal deliberative influence. As this article argues, despite setbacks in ratification, citizen-driven initiatives are likely to remain a durable feature of future constitution-making. Chile’s experience offers valuable lessons for comparative constitutional studies, particularly regarding how CIs can be effectively embedded within constitution-making frameworks to enhance democratic legitimacy and foster inclusive deliberation.

This article examines Chile’s innovative application of the CI in its two recent constitution-making processes. Methodologically, this study adopts a qualitative case study approach, focusing on how the CI was designed, implemented and received within these processes. The analysis draws on primary sources, including official reports from the Technical Secretariat for Popular Participation (Secretaría de Participación Popular 2022) and the Executive Secretariat for Citizen Participation (SEPC) (Secretaría Ejecutiva de Participación Ciudadana 2023; Secretaría Ejecutiva de Participación Ciudadana 2024). Secondary sources include scholarly studies (Suárez Antón Reference Suárez Antón2019; Soto and Suárez Reference Soto and Suárez Antón2024), legal commentaries and comparative constitutional law literature. A process-tracing method was applied to map the regulatory design, the stages of implementation, citizen uptake and the CI’s influence on constitutional outcomes. Quantitative data, such as the number of initiatives submitted and endorsements collected, were analyzed to assess participation levels. This study acknowledges several limitations. The reliance on digital platforms may have introduced demographic biases, given persistent disparities in internet access and digital literacy across Chile’s regions. The absence of qualitative data, such as participant interviews or surveys, restricts deeper insight into citizens’ motivations and experiences. In addition, while official reports are comprehensive, they reflect institutional perspectives that may not fully capture broader public perceptions of the CI’s legitimacy and effectiveness. Future research could address these gaps through mixed-methods approaches that integrate quantitative analysis with qualitative fieldwork.

The article advances the following three core arguments. First, Chile’s CIs met the three defining standards typically associated with CIs in legislative processes (see Table A1): (i) eligibility of initiators, with citizen sponsorship and submission thresholds; (ii) formal and substantive rules governing proposals, including content limitations; and (iii) differentiated procedural treatment during deliberation, allowing proponents to influence debate. In both processes, the CI mechanism adhered to these principles, granting equal status to citizen-submitted initiatives alongside those introduced by elected members.

Second, the article analyzes the measurable impact of Chile’s CIs on both constitutional drafts produced during the 2021–2023 processes. Over a million Chileans submitted and endorsed proposals, using dedicated digital platforms that aggregated diverse viewpoints and enabled citizen input to shape constitutional deliberations. This contrasts with earlier participatory efforts, where citizen input was often symbolic or subject to significant institutional filtering (Welp and Soto Reference Welp and Soto2019).

Third, the Chilean case represents an example of fully digitalized constitution-making participation. Leveraging the country’s advanced digital infrastructure, particularly the Clave Única digital identification system, Chile provided a scalable and secure platform for citizen engagement. This experience demonstrates how digital tools can transform traditional state–citizen relations, making constitution-making processes more participatory and inclusive (Noveck Reference Noveck2009; Fung Reference Fung2015).

In comparison, while the ECI and CoFoE illustrate innovations in supranational participatory democracy, they remain primarily consultative and lack binding mechanisms for citizen proposals (Suarez Anton Reference Suárez Antón2019; Alemanno and Organ Reference Alemanno and Organ2021; Geuens Reference Geuens2023; Jančić Reference Jančić and Jančić2023). By contrast, Chile’s CI was structurally embedded in the drafting process itself, ensuring that citizen proposals carried formal deliberative weight. This model of institutionalized digital participation offers important lessons for future constitutional reforms. Despite the rejection of both constitutional drafts, Chile’s CI demonstrates the potential for digital participation mechanisms to evolve as a key feature of constitution-making worldwide. Taiwan’s recent experiments in digital democracy further underscore this emerging global trend (Tang and Weyl Reference Tang and Weyl2024).

This article is structured in three sections. Following this introduction, the second section analyzes the novel participatory features of Chile’s CIs, focusing on their regulation and implementation during both the Constitutional Convention (2021–2022) and the participatory stage of the Constitutional Council (2023). The third section concludes by identifying lessons from Chile’s experience for the future development of CIs in comparative constitution-making.

The CI in the Chilean constitution-making process

The crisis of Chile’s political institutions and the demand for a new Constitution have been central concerns for social movements in recent decades. The massive protests starting in October 2019, known as the estallido social, were not spontaneous but built upon a history of social mobilization. Key precedents include the 2006 protests led by secondary students demanding educational reforms, the 2012 university student demonstrations advocating for free and quality education, the 2016 mobilizations against the privatized pension system and the 2018 feminist movement’s protests addressing gender inequality and violence. These successive waves of activism reflected deep public dissatisfaction with the country’s institutional framework, particularly due to historically low levels of trust in political actors. As of 2022, approval ratings for political parties, Congress and the Government stood at just 2, 3 and 5%, respectively (CEP 2022). In response to this crisis of legitimacy, political institutions embraced the idea of constitutional reform as both a survival strategy and an attempt to rebuild public trust in the political system.

Providing a bigger picture of the two constitution-making processes requires us to first acknowledge their main features. Both undertakings ended up delivering constitutional proposals that failed to gain majoritarian support in national referendums held in a span of over a year: September 2022 to December 2023. Both processes were based on multiparty agreements: Acuerdo por la Paz Social y la Nueva Constitución and Acuerdo por Chile. These agreements were later enforced through extensive constitutional reforms to the current Constitution (mainly Law No. 21,200/2019 on December 24 and Law 21,533/2023). Surprisingly, today, and likely as an unprecedented element in comparative constitution-making, the Constitution’s final chapter XV includes as a ‘dead letter’ two different titles: ‘of the procedure to draft a new constitution of the republic’ and ‘of the new procedure to draft a political constitution of the republic.’ The ad hoc nature of these regulations, designed as extensive constitutional provisions for a single implementation, has been criticized (Negretto and Soto Reference Negretto and Soto Barrientos2022).Footnote 1

In general terms, the first constitution-making process unfolded along the following path: First, a technical commission was appointed by Congress to draft the details of the constitutional reform that paved the constitutional change agenda. Then, an entry national referendum in October 2020 was held asking the people if they wanted a new constitution and the type of the constituent body: a fully elected constitutional convention or a mixed convention including the presence of acting parliamentarians. The first type won by a considerable margin, and a Constitutional Convention including 155 representatives with a high number of independents, gender balanced and with reserved seats for the indigenous population was elected in May 2021. The Convention was installed on July 4, 2021, and ended its term exactly 1 year later, on July 4, 2022.

Unlike the second process, the Constitutional Convention’s constitutional regulation did not mention anything related to citizen participation. It was the Convention itself that included in its internal regulation an ambitious process of public participation, including different mechanisms that we will examine later.

After the first constitutional proposal was rejected in September 2022, the second constitution-making process was designed in an attempt to avoid repeating what were seen as the mistakes of the first process. This second attempt at constitutional replacement had a stronger presence of the political parties, included a 24-member Expert Commission and a smaller constituent body of 50 elected representatives now called the Constitutional Council, all of which were bound by 12 substantive ‘institutional and fundamental bases’ that the draft constitution must conform to before being submitted for ratification in a referendum (Article 154, Constitution). Also, the internal regulation of the constitutional bodies was not delegated to the constituent body itself, but rather established by Congress (Article 153, Constitution). Article 153 of the Constitution established the following: ‘The regulations will include mechanisms for citizen participation, which will take place once the Constitutional Council is established and will be coordinated by the University of Chile and the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, through methods that allow the participation of all accredited universities. These mechanisms will include the popular initiative of norms’ (Article 153, Constitution).

The second process was also shorter. The Expert Commission was installed in March 2023, and it produced a preliminary constitutional draft that worked as the basis for the work of the elected Constitutional Council. The Council was elected in May 2023 and installed in June that same year. Both constitutional bodies, including a third constitutional body called the Technical Admissibility Committee (in charge of resolving any internal dispute or violation of the substantive or procedural limitations), were automatically dissolved by law on November 7, 2023, weeks before the national referendum scheduled for December 17, 2023. The participatory stage in this constituent process only began after the installation of the elected Council.

In what follows, we will examine how CIs were regulated in both constitution-making processes, their general implementation and describe critically examples of how they influenced the outcome of both constitutional proposals.

In the first constitution-making process (2021–2022)

As previously mentioned, the constitutional reform outlining the primary features of the first process (2021–2022) did not refer to public participation during the Convention’s drafting of the constitutional proposal. Reflecting the overall context of this first process, it was expected that the Convention would actively embrace various participatory mechanisms. Upon its commencement on July 4, 2021, the Convention prioritized electing its governing board and establishing its internal regulations. After nearly 3 months of effort, these regulations were approved, facilitated by the formation of eight provisional commissions.Footnote 2 Notably, these commissions conducted public hearings involving various civil society organizations. For instance, the commission responsible for drafting the internal general regulation held over 100 hearings. By the end of this initial organizational stage, the Constitutional Convention had adopted four core regulations to govern its activities: (1) the General Regulation, (2) the Regulation on Popular Constituent Participation, (3) the Regulation on Indigenous Participation and ConsultationFootnote 3 and (4) the Ethics Regulation.Footnote 4 This article focuses on the Regulation on Popular Constituent Participation, formally drafted by one of the provisional commissions and subsequently adopted by the plenary of the Constitutional Convention under its decision-making authority. Officially titled the Regulation for Mechanisms, Structure and Methodologies of Constituent Participation and Popular Education, it established the framework for citizen involvement throughout the drafting process.Footnote 5

The CI was regulated along with other mechanisms of citizen participation, such as public hearings, Community Councils (Cabildos Comunales), self-convened meetings, national deliberation days, deliberative forums and intermediate referendums, among others.Footnote 6 The CI was one of the first participation mechanisms to be implemented, along with public hearings and Community Councils. Specifically regarding the timeline, the CI received proposals from mid-November to mid-December 2021. Sponsorship signatures to support the proposals could be registered until February 1, 2022. The regulation defined the CI as ‘a mechanism of popular participation through which an individual or group of individuals can submit a proposed norm on a constitutional matter to the Constitutional Convention’ (Article 31).

There were two main bodies governing the participatory mechanisms. On the one hand, the Popular Participation Commission, defined by the regulation as a functional and permanent body, tasked with directing and supervising the design and implementation of popular participation mechanisms and methodologies (Article 16). This Commission included at least 21 members of the Convention, ensuring representation from indigenous peoples, maintaining gender parity and incorporating members from the seven thematic commissions of the Convention (Article 17). Its responsibilities included overseeing the work of the Technical Secretariat for Popular Participation, coordinating with various Convention bodies to implement the established mechanisms for participation and popular education (Article 18). The Technical Secretariat for Popular Participation was tasked with implementing participation mechanisms and was required to produce periodic reports detailing their implementation and results (Article 19). The Secretariat was led by a director and consisted of 16 individuals with recognized expertise in constitutional matters, citizen participation methodologies, linguistic analysis, intercultural knowledge, quantitative and qualitative data analysis, information technologies and other relevant disciplines essential for fulfilling its duties (Article 20). The Convention’s Board of Directors selected these 16 individuals, who were then approved by the Convention Plenary (Article 22). The Secretariat’s primary functions included proposing to the Commission the design of methodologies and implementation procedures for each participation mechanism, establishing systems to ensure the systematization and traceability of the information received and developing a proposed participation timeline (Article 23).

To submit a CI, individuals or groups were required to first register in the Public Participation Registry and complete a form provided by the Technical Secretariat for Popular Participation. This form included a rationale for the proposal, a brief summary of its proponents and background and a draft text for the new Constitution (Article 33). In addition, individuals or organizations could each submit up to seven CIs (Article 33). Furthermore, the Popular Participation Commission could reject initiatives that violated International Human Rights Treaties ratified by Chile, thereby preventing their publication on the digital platform (Article 33). Once approved, initiatives were published on the Convention’s Digital Platform, where a signature collection process began. Signatures could be submitted by individuals over 16 years old, including Chilean nationals, foreign residents in Chile and Chileans abroad (Article 34). Moreover, the Technical Secretariat oversaw the mechanisms for digital and physical signature collection, ensuring authenticity, transparency, data protection and platform security (Article 34). In addition, the Secretariat evaluated the relevance of initiatives for constitutional discussion and reported to the Popular Participation Commission for its resolution (Article 35). Importantly, only CIs with at least 15,000 signatures from a minimum of four regions were formally treated as norm proposals from Convention members and were discussed and voted on (Article 35). Finally, all proposals remained on the online public repository, allowing for additional signatures throughout the deliberation process (Article 35).

Regarding digital constitution-making and in accordance with the regulations, the Convention established a ‘Digital Platform for Popular Participation,’ which served as a crucial link between individuals, organizations, communities and the Convention itself. This platform functioned as a tool for facilitating participation, supporting the systematization of inputs, promoting popular constitutional education, maintaining a database and providing accessible information (Article 26). Its primary objectives included offering digital mechanisms for popular participation, streamlining the receipt of inputs and aiding in the organization of various participation processes (Article 27).

According to the Final Implementation Report of June 2022 from the Technical Secretariat for Participation, the Digital Platform was a system developed and managed by the Ucampus Technology Center, initiated within the University of Chile’s Faculty of Physical and Mathematical Sciences. This website served as a central hub for various participation mechanisms, including CIs, Indigenous Peoples’ Initiatives and Councils and Meetings, and featured a tool for searching constitutional norms. Through the platform, users were required to log in using their Clave Única or cédula de identidad to access the platform’s components. The ‘Clave Única’ in Chile is an authentication and electronic signature system provided by the State, allowing citizens and residents to securely access a wide range of online services offered by public institutions, such as the Civil Registry, the national health system, the Ministry of Education, pension procedures or tax declarations. Upon logging in, individuals needed to complete a Participation Registration (Secretaría de Participación Popular 2022: 25). The platform allowed users to submit CIs and support initiatives of interest until the required seven endorsements were reached. It provided detailed reporting on participation results, including the total support received by initiatives, those that achieved the necessary endorsements for constitutional discussion, all available initiatives and participant numbers. Users could filter initiatives by commission and sort them by support or date, with each initiative displaying sociodemographic statistics about its supporters (Secretaría de Participación Popular 2022: 25).

In addition, the Constitutional Convention created a public registry for individuals and organizations interested in engaging with the different participation mechanisms. The Technical Secretariat for Popular Participation was responsible for providing a registration form for both individuals and organizations, available on the Digital Platform and in physical format (Article 28). Consequently, to participate in the Digital Platform, individuals had to create a user account. This process led to the creation of the abovementioned National Participation Registry, ensuring the confidentiality and protection of each user’s personal data. A total of 1,006,314 public registrations were recorded, most of which were completed before the deadline for submitting CIs (Secretaría de Participación Popular 2022: 26).

The digitalization of the initiative process in Chile, along with the inclusion of foreigners residing in the country and citizens over the age of 16 years, introduced innovative elements that align with global best practices in citizen participation, such as those seen in the ECI (Suárez Antón Reference Suárez Antón2020). From a comparative perspective, these features are also present in some of the most successful legislative models, such as those in Austria and Latvia (Suárez Antón Reference Suárez Antón2019). However, the entry requirements for initiatives in Chile appear overly demanding, especially considering that these initiatives are only intended to foster debate within the Constitutional Convention. The necessity of presenting a set of articles for admissibility seems excessive, as a simple, clear statement of the proposal’s subject and objectives could have sufficed.

A critical flaw in the process is the lack of involvement of initiative proponents in the admissibility analysis, coupled with the lack of technical or economic support for developing and promoting the initiatives. These material requirements are more characteristic of ‘strong’ CIs, which involve rigorous controls and are typically submitted for direct citizen approval, as in models like Switzerland or Uruguay (Soto y Suárez Reference Soto and Suárez Antón2024). In such contexts, stricter normative and constitutional standards are expected. Moreover, the procedure was criticized for its lack of deadlines, with only the start and closing dates for proposal submissions and sponsorships being defined. The absence of deadlines for observations and subsequent corrections introduced a degree of flexibility in the process, which undermined its effectiveness.

Let us now proceed to the evaluation of the CIs process, drawing on the official data compiled by the Technical Secretariat for Popular Participation in its Final Implementation Report (June 2022), as well as complementary analysis by Soto and Suárez (Reference Suárez Delucchi2024). The following assessment considers both quantitative data and qualitative insights. We begin by reviewing the numerical data reported by the Secretariat, which serves as the primary source of official participation records. This includes the number of initiatives submitted through the Digital Platform for Popular Participation, their admissibility outcomes, the signature collection process and subsequent deliberations by the Constitutional Convention’s commissions. The benchmarks for this evaluation are established by the Convention’s own regulatory framework – specifically, the requirements set out in the Regulation for Mechanisms, Structure and Methodologies of Constituent Participation and Popular Education. These requirements included, among others, criteria for the admissibility of proposals, signature thresholds for advancing initiatives to formal debate (a minimum of 15,000 signatures from at least four regions) and the subsequent treatment of proposals within the Convention’s deliberative process. According to the Final Implementation Report, a total of 6,105 initiatives were submitted through the digital platform. Of these, 2,350 were declared inadmissible by the Popular Participation Commission and the Technical Secretariat, based on noncompliance with the regulatory criteria. In addition, 1,259 initiatives were flagged for observations but were not corrected by their proponents within the established timeline. Ultimately, 2,496 initiatives were published on the platform, and 78 successfully met the threshold of 15,000 signatures, qualifying them for formal discussion. Among these, five were debated across multiple commissions, leading to a total of 83 Citizens’ Initiatives being formally examined in the Convention’s thematic commissions.

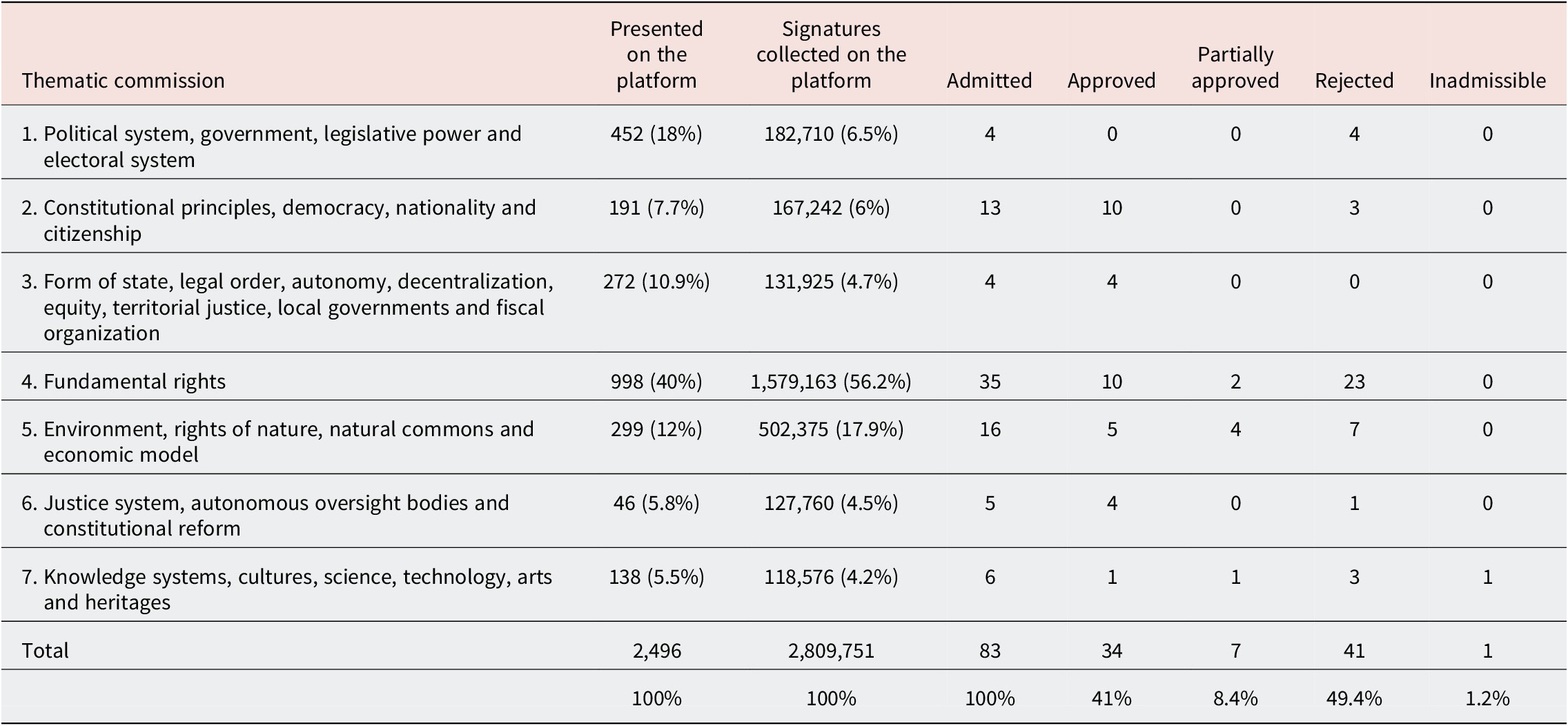

The Final Implementation Report highlights that a total of 2,809,751 sponsorships were registered from 1,005,771 individuals, with 47.8% of participants identifying as women and 39.9% as men. According to the report, there was a substantial degree of alignment between the CIs that garnered popular support and the draft text produced by the Constitutional Convention. Of the 78 initiatives that met the threshold of 15,000 signatures, 29.5% were fully incorporated into the draft, 59% were partially incorporated – meaning only some of their proposed content was included – and ~11.5% were not reflected at all in the final text (Secretaría de Participación Popular 2022: 96). These figures suggest a relatively high level of responsiveness to citizen proposals and offer a quantitative basis for evaluating both the inclusiveness and effectiveness of the participatory mechanisms established by the Convention. However, a closer examination of the process – particularly regarding the most popular yet ultimately excluded initiatives – reveals important limitations. Notably, the rejection of high-profile initiatives, such as the widely supported proposal on pension reform, underscores the gap between citizen demands and the final decisions of the Convention. It is important to note that the Final Implementation Report was issued while the draft constitution was still under review by the Harmonization Commission, which may have resulted in an overly optimistic account of the participatory process. In many respects, the report lacks critical self-reflection, failing to address the consequences of excluding initiatives with significant public backing and the potential impact of these decisions on the legitimacy of the constitutional process as a whole.

Table 1 illustrates the distribution of CIs among the permanent thematic commissions of the Constitutional Convention, with the highest concentration in the Commission on Fundamental Rights. Of the 83 CIs that were introduced into the constitutional debate, 34 were approved by their respective commissions, 7 were partially approved, 41 were rejected and 1 was deemed inadmissible.

Table 1. CI admissions and results (2021–2022)

Source: Soto and Suárez (Reference Soto and Suárez Antón2024).

However, the landscape of approval and rejection shifted significantly during the subsequent plenary discussions. To accurately assess the impact of each CI on the final draft of the proposed new constitution, a detailed individual analysis is required – an endeavor that goes beyond the scope of this study. Instead, our analysis will concentrate on reviewing only the most emblematic examples. As previously noted, the Commission on Fundamental Rights stands out due to its significant impact and the volume of CIs that it reviewed, representing over 40% of the total. One notable example is the CI titled ‘Villagers for the Right to Decent Housing,’ which involved extensive community participation and garnered 21,896 signatures. This initiative was incorporated into Article 51 of the final constitutional draft, establishing the right to decent and adequate housing and detailing the State’s role in managing public land and preventing speculation. Similarly, the CIs ‘For the Constitutional Recognition of Domestic and Care Work’ and the ‘Right to Care’ were included in Articles 49 and 50, respectively. Article 50 affirmed the right to comprehensive and dignified care, with the State tasked with ensuring a universal, culturally relevant care system supported by adequate financing.

In addition, the CI titled ‘The Right to Social Security,’ presented by the National Coordination of Workers ‘NO + AFP,’ was approved and partially incorporated into Article 45, emphasizing the principles of universality and solidarity. This initiative sought to establish a social security system based on state participation and collective funding, departing from the individual capitalization model managed by the Administradoras de Fondos de Pensiones (AFP). In contrast, the highly supported CIs ‘Not with My Money’ and ‘It’s My Money and That’s It,’ which gathered 60,852 and 16,944 signatures, respectively, were rejected by the Commission, generating controversy. These initiatives, backed by groups advocating for the individual ownership of pension funds, aimed to ensure that workers’ savings in AFPs remained untouchable, preventing state intervention in their use or redistribution. They were rooted in the principles of freedom of choice and the protection of the individual capitalization system, asserting that pension funds belong exclusively to each contributor. The opposing nature of these initiatives highlights the broader polarization surrounding the future of Chile’s pension system. While one promoted a solidarity-based, state-managed model, the other defended individual capitalization and contributors’ autonomy. Although neither initiative ultimately determined the final content of the constitutional draft rejected in 2022, their impact on the public debate was significant, demonstrating that pension reform remains one of the most contentious issues in Chile, and that any future policy changes must account for these divergent perspectives.

Another significant case involved a CI with over 27,000 supporters related to maintaining the bicameral system called ‘A bicameral legislative power in Chile,’ which was rejected by the majority of the Commission on Political System, Government, Legislative Power and Electoral System. Despite its rejection, this CI contributed to moderating the initial proposal to replace the Senate with a new chamber known as the Regional Chamber (Soto and Suárez Reference Soto and Suárez Antón2024).

Public discontent became increasingly evident following the rejection of several high-profile CIs, most notably ‘Not with My Money,’ which had gathered substantial public support. The decision by the Constitutional Convention to exclude these proposals, particularly those related to the future of the pension system, generated widespread controversy and dissatisfaction among certain sectors of the population. This sentiment was reflected in the results of the CADEM survey conducted on April 1, 2022, which showed growing public opposition to the proposed constitution, with 46% of respondents expressing support for rejection compared to 36% favoring approval. Importantly, although some widely supported initiatives – such as those affirming the right to housing, social security and care – were incorporated, either fully or partially, into the final draft of the Proposed New Constitution, these inclusions were not sufficient to overcome broader concerns and public skepticism. Many citizens perceived the exclusion of key proposals, along with other contentious aspects of the draft, as undermining the Convention’s responsiveness to popular demands. Consequently, public support for rejecting the Proposed New Constitution continued to rise in the months leading up to the plebiscite. Ultimately, this trend culminated in a decisive outcome: 62% of voters rejected the draft constitution in the national plebiscite held on September 4, 2022 (Segovia y Toro 2022). This result underscores the complex relationship between citizen participation, institutional decision-making and the perceived legitimacy of the constitutional process.

In the second constitution-making process (2023)

In contrast to the first constitution-making process, the second experience explicitly mandated the inclusion of citizen participation mechanisms, including CIs, as outlined in Article 153 of the Constitution. This explicit requirement, coordinated by the University of Chile and the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, highlighted the CI mechanism as a successful model for participation from the previous process. It reflects the consensus among political parties in Congress regarding its efficacy. Furthermore, the direct constitutional mandate to these universities for coordinating the process marked a significant innovation in comparison. As we will discuss, the new regulations are built upon many aspects of the previous Convention experience. It was also a form of addressing the errors identified in the first process.

The mandate to the University of Chile and the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile established a joint SEPC. The regulation defined SEPC as an ‘inter-institutional technical’ body, whose integration and structure were to be determined by both universities. SEPC comprised academics, many of whom had been involved in the previous process.Footnote 7 According to the regulation, the Secretariat ‘must design, coordinate, implement and systematize’ citizen participation mechanisms. The regulation also allowed SEPC to receive support from other universities and civil society institutions, with a mandate to include groups or individuals typically excluded from public discussion (Article 106, Reglamento de Funcionamiento). SEPC had to report its work to the Constitutional Council’s Secretariat (Article 106, Reglamento de Funcionamiento). A critical element in its institutional design was the regulation’s provision for ensuring SEPC’s funding and logistical support. The regulation stated that ‘the coordinating universities must be provided with the necessary financial resources to carry out the citizen participation process’ (Article 107, Reglamento de Funcionamiento). This support could be secured through specific agreements between SEPC and state bodies.

According to the regulation, the SEPC was also responsible for designing and implementing the digital platform, supporting citizen participation, promoting citizen influence in drafting the constitutional text proposal and providing constant feedback. Here, it is relevant to highlight the continuity that the University of Chile’s digital platform (ucampus) had through a new interactive website that concentrated the different participatory mechanisms. The regulation required the SEPC to issue ‘at least’ one final report to the Constitutional Council on the implementation and results of the participation mechanisms and the proposals submitted by various individuals and groups (Article 106, Reglamento de Funcionamiento). It is worth noting, in this respect, that this requirement addressed the poor performance of the previous process, where reports lacked a minimum level of rigor. In September 2023, the output of the CIs was synthesized in a 284-page report. Also, in January 2024, after the final rejection through the referendum, an additional and larger 471-page report examined the impact of the CI in the constitutional proposal.

Following the constitution-making agenda, beginning on April 6, 2023, SEPC was authorized to organize preparatory activities for citizen participation before the installation of the Constitutional Council in June. These activities included civic education and explanations about the constituent process and the available citizen participation mechanisms (Article 104, Reglamento de Funcionamiento). In addition, Article 105 tasked the SEPC, in collaboration with the National Congress Library, to work on a significant report. This report involved systematizing the forms of citizen participation developed in previous constituent processes, starting from 2016 onward with Michelle Bachelet’s first attempt at constitutional replacement, where information was already available.Footnote 8 Particularly, for CIs, the process followed a structured timeline. From May 16 to June 6, 2023, individuals and organizations could express interest and preregister their CIs. The official submission period then took place from June 7 to June 21, 2023. Following this, on June 23, 2023, the submitted initiatives were published, and the collection of citizen endorsements occurred between June 23 and July 7, 2023. Finally, on July 10, 2023, the validated CIs were submitted to the Constitutional Council (Secretaría Ejecutiva de Participación Ciudadana 2023: 18).

Compared to the 2021–2022 process, this clear timeframe enabled a more organized and structured approach, contributing positively to the overall process. The timely presentation of CIs to the Constitutional Council was essential for their overall impact, as it ensured that they were formally considered before the deliberative body began its discussions, deliberations and agreements. This aspect was a notable flaw in the previous constitutional process, where many CIs were introduced after substantial agreement had already been reached among each Commission of the Convention. In contrast, the second process successfully addressed this issue by ensuring that all CIs were submitted before the installation of the Constitutional Council (Secretaría Ejecutiva de Participación Ciudadana 2024: 6–7).

According to the regulations (Title VI), citizen participation procedures had to be systematized and, when feasible, provide ‘feedback’ to participants (Article 98, Reglamento de Funcionamiento). The regulations also required that the results from these participation mechanisms be promptly delivered to the Constitutional Council to enhance its deliberative work (Article 98, Reglamento de Funcionamiento). The four participation mechanisms included CI, public hearings, deliberative citizen dialogues and citizen consultations (Article 99, Reglamento de Funcionamiento).

Unlike the previous process, where CIs were formulated without a preestablished draft, the new regulations mandated that each CI, whether proposed by individuals or organizations, was framed as an amendment to specific articles of the draft Constitution prepared by the Expert Commission. These amendments could involve deleting, replacing, modifying or adding norms, as outlined in Article 100 of the Reglamento de Funcionamiento. SEPC was responsible for providing the digital platform through which citizens could submit amendment requests, ensuring compliance with formal admissibility criteria. Each submission had to identify the provisions to be amended, provide the proposed text, offer a rationale and include the authors’ identification, verified via the Clave Única del Servicio de Registro Civil e Identificación. SEPC reviewed submissions for compliance and made them publicly available for digital signature collection within a specified timeframe. Unlike the previous process, which allowed ~4 months for submissions, the new one limited submission and signature collection to 30 days following the Constitutional Council’s installation (from June 15 to July 15, 2023). CIs that garnered 10,000 signatures from at least 4 regions were forwarded to the Constitutional Council for debate and resolution. Citizens could sign up to 10 initiatives, an increase from 7 in the prior process, and once submitted, no amendments to these initiatives were permitted. In addition, SEPC facilitated a platform feature allowing voluntary merging of CIs, enabling collaboration among authors. SEPC also assumed several responsibilities not explicitly outlined in the regulations, such as lowering the age requirement for CI sponsors to 14 years, compared to 16 years in the previous process. A Consultative Committee, comprising representatives from universities and civil society organizations, was established to receive suggestions and observations throughout this mechanism. SEPC also established formal admissibility criteria, which included requirements that CIs addressed norms within the same chapter of the draft, linked to the correct article or chapter, provided a proposed wording and rationale and avoided deleting or replacing the entire draft or a chapter. The CIs were also required to maintain coherence between the title, proposed wording and rationale, be clearly formulated, address legal matters and refrain from using offensive or derogatory language. To ensure compliance with the 12 institutional bases established in Article 154 of the Political Constitution of the Republic and international human rights treaties, SEPC informed proposers if their CI potentially violated these bases, although it could not declare a CI inadmissible on these grounds. If a proponent insisted on including such content, a statement was added to the publication noting the potential infraction (Secretaría Ejecutiva de Participación Ciudadana 2023: 17).

For organizations, only their designated representative was allowed to submit CIs. Individuals aged 14–18 years had to declare that they had parental or legal guardian authorization to propose a CI. To enhance the participation of indigenous peoples and the Afro-descendant Tribal People, provisions were made for individuals and organizations to identify as belonging to these groups and to indicate if their CI was relevant to these communities. To prevent the fragmentation of proposals and support, a voluntary process was established allowing authors to unify their initiatives by sharing their contact information with other proponents. All submitted CIs underwent a thorough verification process to ensure compliance with admissibility criteria, which involved three successive levels of review: an initial review by law students selected by collaborating universities, followed by a review by fifth-year law students or law graduates and a final validation by academic experts. Proponents were given the opportunity to correct any identified errors, with explanations and the necessary corrections. In addition, there was a mechanism for the public to request a review of rejected initiatives. The presentation and support phases for initiatives were separated to ensure equal time for support seeking and to allow for a thorough review of all submissions by SEPC. Workshops were conducted before and during the presentation phase to explain the methodology, admissibility criteria and platform usage, with email and telephone support available throughout the process (Secretaría Ejecutiva de Participación Ciudadana 2023: 18).

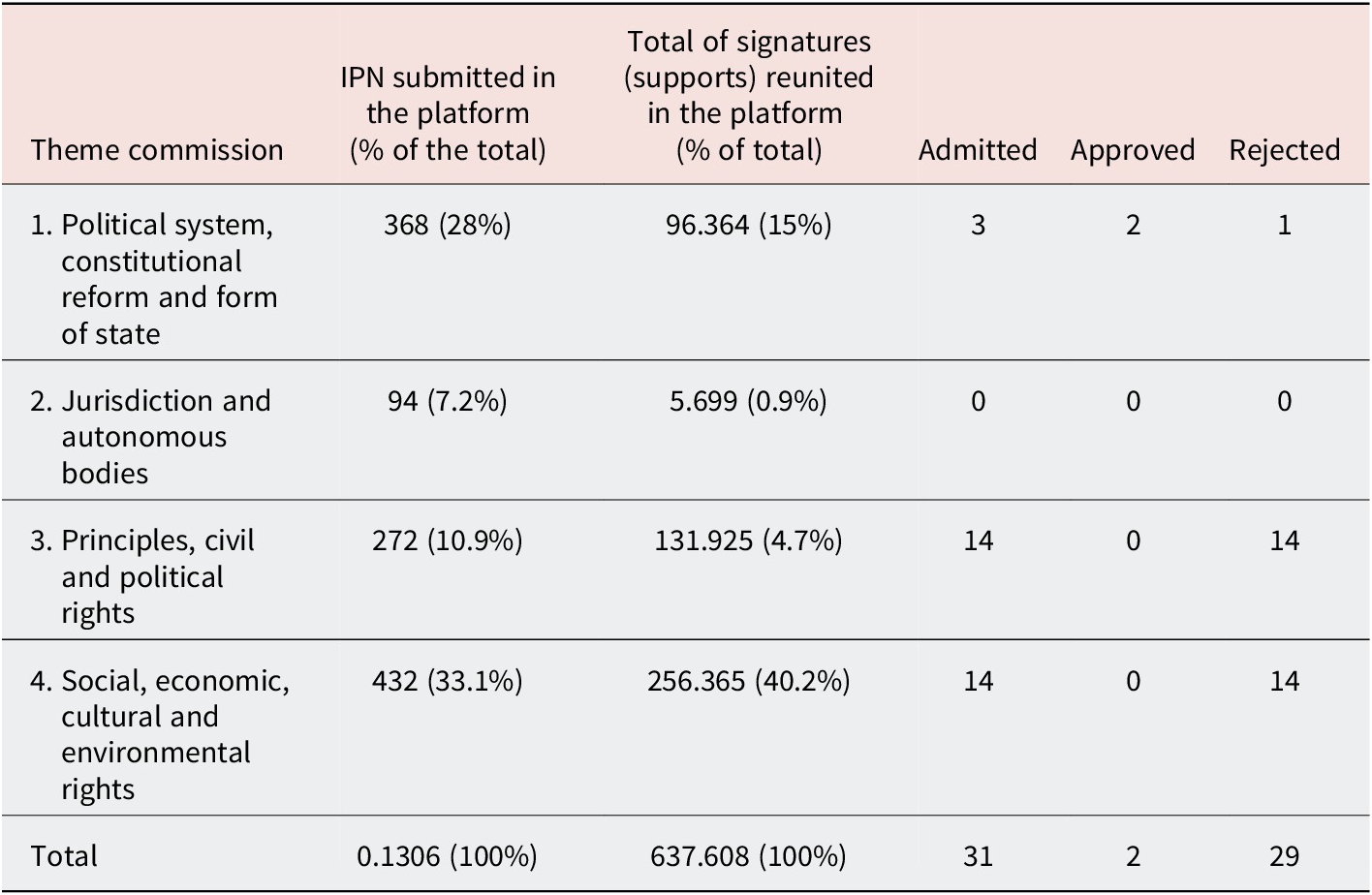

A total of 1,602 CIs were submitted, representing a significant decrease from the 6,105 initiatives in the previous process. Of these, 241 were not resubmitted after a request for corrections, 52 were rejected and 3 were withdrawn, resulting in 1,306 published initiatives (Secretaría Ejecutiva de Participación Ciudadana 2023: 19). In contrast, during the 2021–2022 period, 3,609 initiatives were deemed inadmissible, and only 11 of these were considered to potentially infringe upon the institutional bases established in Article 154 of the Constitution. Notably, 31 CIs received the required 10,000 signatures from at least 4 different regions within the specified timeframe, qualifying them for discussion in the Constitutional Council, compared to 78 in the previous process. These initiatives were subsequently reviewed by the Council’s board and processed by the relevant committees (Secretaría Ejecutiva de Participación Ciudadana 2023: 19). Each submitted proposal included details on the initiatives’ identification and the total number of signatures received, representing the aggregate support for each grouped initiative (Informe 2023, SEPC 20). Statistical data and characterization of the authors and supporters relevant to each commission’s scope were also provided (Secretaría Ejecutiva de Participación Ciudadana 2023: 20). Participants could support up to 10 CIs, but the average was 2.7. The number of individuals sponsoring initiatives was notably lower, with 236,474 supporters (23% women/70.3% men) compared to 1,005,771 (47.8% women/39.9% men) in the previous process, resulting in a total of 637,608 endorsements versus 2,809,751 previously. Only 21.1% of CI authors were identified as organization representatives, although this representation increased to 93.5% among initiatives that received over 10,000 signatures. As detailed in Table 2, the most popular themes focused on Chapter II of the draft for the new Constitution – fundamental rights and freedoms, constitutional guarantees and duties – comprising 40.1% of the proposals and 63.9% of the signatures. This preference was also evident within the two commissions addressing Chapter II of the draft (Secretaría Ejecutiva de Participación Ciudadana 2023: 20).

Table 2. CI admissions and results (2023)

Source: Suárez Delucchi (Reference Soto and Suárez Antón2024).

As noted in Table 2, only two CIs were formally approved in Theme Commission number 1: the CI called ‘For a State without pítutos’ supported with 18,706 signatures and promoted by the NGOs Pivote, Horizontal and Ideapaís.Footnote 9 This CI sought to establish a new regime for hiring, promotion and dismissal of public officials. Although some corrections were made based on the proposed articles, they were subsequently substantially modified, distorting the CI’s original intent. Another approved initiative with 11,173 signatures was called ‘Regulations for respect and dignity for firefighters in Chile,’ presented by the Citizens Committee for the Dignity of Firefighters in Chile.Footnote 10 As a result of this initiative, a new article was incorporated into the draft of the proposed new constitution, specifically inserted after Article 122. This new provision included two of the three sections proposed by this CI, recognizing and regulating the role of firefighters in Chile.Footnote 11 However, during later stages of the constitutional process, the Expert Commission ultimately decided to delete this article from the draft. It is, in this context, essential to highlight that, as CIs implied concrete regulatory proposals for articles integrating the Expert Commission’s preliminary draft, partial approvals, such as those in the previous process, were not possible. Only if the entire text was approved could corrections to the articles be considered pertinent. Rejection, on the other hand, entailed excluding the articles entirely, although certain content could eventually be assessed in amendments of unity of purpose, as happened on several occasions. However, as we will show below, this was not an obstacle for CIs having a clear effect on the content of the constitutional proposal.

To evaluate the CIs’ impact on the constitutional process and provide feedback to their proposers, SEPC developed an analysis of how each of the 31 CIs influenced various stages of the Constitutional Council process. The report declared: While the impact of citizen participation can be assessed according to different criteria and variables, in this report, the impact of the CIs refers to ‘the influence or effect that the themes raised in the respective citizen proposals had on the constitutional process’ (Secretaría Ejecutiva de Participación Ciudadana 2024: 5). The SEPC report categorized this impact into four levels. A first level considered the CI authors’ presentations to each respective theme commission. This level, open to all CIs, involved the opportunity for authors to facilitate explanations, exchange of ideas and discuss their initiatives with the Council members. A second level of impact corresponds to amendments presented by Council members or unity of purpose amendments, according to Article 74.3 of the regulations, which incorporated a core or essential idea from the respective CI. This situation arose because the CIs were received before the deadline for the presentation of amendments by Council members, enabling the total or partial incorporation of some of the CIs (Secretaría Ejecutiva de Participación Ciudadana 2024: 5). A third level referred broadly to the contribution of each CI into the overall constitutional deliberation. In other words, to the debate and discussion that took place at any stage of the process (Secretaría Ejecutiva de Participación Ciudadana 2024: 6). Finally, a fourth level involved the inclusion of core ideas or proposals from CIs into the constitutional text, in the various stages of discussion either through direct approval or amendments (Secretaría Ejecutiva de Participación Ciudadana 2024: 6–7).Footnote 12

We end this section discussing the three conclusions learned from the 2024 SEPC Report. First, this report positively evaluates the Constitutional Council’s decision to allow authors of CIs to present their proposals, a step not initially outlined in the regulations. Unlike the 2022 process, where such opportunities were limited, the 31 CI authors were able to present and justify their proposals before the Constitutional Council’s commission. This facilitated direct exchanges between CI authors and Council members, allowing for the resolution of doubts and preliminary discussions. The public nature of these sessions, which were streamed online, also enhanced public engagement with the debates surrounding the proposals (Secretaría Ejecutiva de Participación Ciudadana 2024: 461). Second, the potential impact of CIs was further amplified by the amendments introduced by Council members, which partially or fully integrated some of the CI proposals. By submitting their CIs before the deadline for amendments, the proponents ensured that their proposals could be considered in the drafting process. This approach allowed for a broader impact than simply accepting or rejecting the CIs outright. The amendments reflected a range of approaches, from fully adopting CI proposals to incorporating parts of them or modifying their content while maintaining their core orientation (Secretaría Ejecutiva de Participación Ciudadana 2024: 461).Footnote 13

Third, CIs’ incorporation into the final constitutional text varied significantly. None of the CIs were entirely approved as presented. As the 2024 report shows, out of the 31 CIs admitted, proposals from 22 CIs were incorporated. This took place in later stages of the constitutional process, either through partial approval or through the adoption of amendments by Council members, that fully, partially or with modifications, included the CIs’ normative proposals (Secretaría Ejecutiva de Participación Ciudadana 2024: 463). In this context, the 2024 SEPC’s report distinguished the degree of impact of each CIs by dividing it into five categories: (i) CIs fully incorporated through amendments by Council members (2 cases)Footnote 14; (ii) CIs proposals significantly incorporated (10 cases) and (iii) minor incorporated (10 cases); (iv) CIs not incorporated, although considered in an earlier stage (2 cases), which, according to the report, played a significant role in generating discussion and influencing broadly public opinionFootnote 15 and, finally, (v) CIs not considered in any stage at all (7 cases).Footnote 16 Of course, as the report itself recognizes, this CI distinction is at least polemic and ‘open to debate’ (Secretaría Ejecutiva de Participación Ciudadana 2024: 464).

Here, we focus on discussing some symbolic examples from the second and third categories, that is, significant and minor incorporations. The most popular initiatives are as follows: ‘Chile for animals’ (No. 4,131), sponsored by various animal rights organizations, which garnered the highest number of signatures (25,415), sought originally to incorporate a new articleFootnote 17 in the draft’s constitution Chapter XIII: Environmental Protection, Sustainability and Development. It was finally partially included as a state and individual’s duty to protect animal welfare and promote respect for animals through education (Article 37.8 of the constitutional proposal). On the other hand, the second most voted initiative (24,505 signatures), ‘Not with my money,’ (No. 2,507), a CI protagonist also in the first constitution-making process, aimed to guarantee the ownership and inheritability of pension savings.Footnote 18 While this CI was formally rejected in the respective commission, as seen in Table 2, the final version of the right to social security provision included the central aspects of the CI proposal in Article 16.28 letter (b).Footnote 19 Another example of significant incorporation was observed in CI ‘Public Education for Chile’ (No. 5,127), where the constitutional text introduced the recognition of public education – a provision absent in the Expert’s Draft Proposal – mandating that the state provides public, pluralistic and quality education at all levels, with a guarantee of funding. Similarly, CI ‘Freedom of Thought, Conscience and Religion’ (No. 6,739) led to an expansion in the constitutional text of the right to live according to one’s religion or beliefs, to transmit these beliefs and to conscientious objection, even though the initiative specifically addressed individual and institutional conscientious objection (Secretaría Ejecutiva de Participación Ciudadana 2024: 464).Footnote 20 Conversely, minor incorporation was observed in CI ‘Right to Dignified, Safe and Own Housing’ (No. 10,327), as the constitutional text only broadly addressed the exemption from contributions, omitting the CI’s key proposals on defining the right to housing, its standards, territorial planning and land availability. Another example is CI ‘Every Life Counts’ (No. 3,903), where the constitutional text included a mandate for the legislator to protect the life of the unborn – a provision absent from the Expert’s Draft Proposal – but failed to achieve the CI’s central objective of explicitly recognizing the dignity, personhood and right to life of every human being from conception to natural death (Secretaría Ejecutiva de Participación Ciudadana 2024: 466).Footnote 21

Unlike the first constitution-making process, the second process offered a clearer perspective on the significant role that CIs played in shaping the final draft of the proposed new constitution. While both constitutional proposals were ultimately rejected in national referendums, the use of CIs as a formalized mechanism for public participation in constitution-making remains a noteworthy feature of Chile’s recent experience. Although comparable participatory approaches have been employed in other jurisdictions, the Chilean case represents a distinctive innovation – particularly in relation to the CI mechanism – both from a comparative perspective and within the Latin American context. It stands out for the institutionalization of CIs within a constitution-making framework, the scale of digital engagement and the structured procedures established for submitting, supporting and reviewing citizen proposals. These elements combined to create a participatory model that was both legally mandated and procedurally robust. As we will discuss in the final section of this article, there are valuable lessons to be drawn from Chile’s constitution-making processes. In particular, the participatory mechanisms employed – despite the political and institutional challenges they faced – constitute one of the lasting legacies of these processes and may inform future attempts at constitutional reform, both in Chile and in other countries seeking to enhance citizen involvement in foundational legal debates.

Conclusion

Broadly speaking, the Chilean case supports the increasing trend toward greater public involvement in constitution-making. As mentioned in the ‘Introduction’ section, the Chilean constituent process matters because it demonstrates how public participation through CIs can contribute to shaping its content and direction. Arguably, the CI is the most original aspect of Chile’s constituent process. Chilean citizens not only elected representatives and participated in the constitutional referendums over the proposals but also played a direct role in the drafting stage through CIs. As this article has shown, while none of the initiatives were entirely approved as presented, several CIs influenced the content of the constitutional proposals – either through partial incorporation or by shaping deliberations – demonstrating their relevance as an innovative mechanism in constitution-making.

At the beginning of this article, we noted that the use of CIs as a mechanism for public participation has recently extended from the legislative sphere to constituent processes. In the Chilean case, this experience should be recognized both for the significant mobilization of over one million people during the signature collection stage and for the influence that CIs had during the deliberations and the drafting of the constitutional proposals approved by the Constitutional Convention in 2022 and the Constitutional Council in 2023. While many CI contributions were incorporated into various articles of the constitutional drafts during the discussion stages, only a portion of these proposals were ultimately retained in the final versions of the constitutional texts that were submitted to national referendums. This distinction is crucial: although CIs shaped certain provisions in the drafts, their impact was more limited in the final constitutional proposals formally presented to the electorate. Nonetheless, the active participation of individuals and organizations promoting these initiatives played a significant role in shaping the national debate and the broader deliberative process throughout both constitution-making efforts.

Chile’s constitution-making experience is also an exemplary model of digital constitution-making, particularly through its formalized mechanism of CIs. The country showcased how new digital technologies could enhance public participation by enabling citizens not only to express their views but also to formally submit and support concrete proposals for constitutional norms. The digital online platform made a significant difference in shaping the final versions of both constitutional proposals by facilitating the submission, endorsement and deliberation of CIs. Chile’s advanced digital registration system enabled a more inclusive and participatory process, demonstrating how digital tools can transform the state–citizen relationship and make democracy more participatory. If only for this reason, the Chilean CI within the constitution-making process is worthy of attention. In this regard, the Chilean experience parallels other participatory innovations, such as the EU’s Multilingual Digital Platform, which was deployed during the Conference on the Future of Europe to collect citizen input across member states in multiple languages. However, Chile’s model stands out for its institutionalized integration of citizen proposals directly into a constitution-making process, supported by clear regulatory frameworks and threshold mechanisms. Both the Chilean and European experiences reflect a growing global trend of leveraging digital platforms to aggregate diverse viewpoints and integrate them into decision-making frameworks.

The two constitution-making processes present a unique comparative opportunity to observe and analyze the evolution of CI implementation in distinct contexts marked by both ongoing practices and innovations. These comparable processes provide different insights into institutional design and procedural aspects. The second constitution-making process, while lacking the same level of enthusiasm and participation as the first, was an enhanced version with improvements in CI regulation aimed at better performance. It is important to highlight these improvements, as they contributed to various dimensions of the process.

Several features should be considered for the future design and improvement of CIs, both in Chile and other constitution and law-making processes globally, to enhance accessibility, inclusiveness and overall effectiveness. One key aspect is allowing CI promoters to continue influencing the drafting of the constitutional proposal even after the formal submission of their initiative to the constituent assembly. In this context, notable improvements already tested in Chile – such as lowering the age requirement for CI sponsors (to 16 years or even 14 years) and reducing signature thresholds (from 15,000 to 10,000 signatures) – could inform future designs elsewhere. In addition, establishing a clear and predictable timeframe for the submission and review of CIs is crucial for providing certainty to both initiative promoters and representatives. More broadly, there is considerable potential for improving dialogue between CI authors and representatives in the constituent body. For example, CIs should be submitted before commissions begin formal deliberations during a preliminary phase when informal agreements on constitutional content have not yet been finalized, thereby increasing their persuasive impact. It may also be worth exploring the possibility of allowing CIs to be resubmitted or revised after gathering additional support at a later stage in the drafting process. In this regard, a comparative analysis of CI regulations across different constitution-making experiences could offer further valuable insights for both Chile and other countries adopting or refining similar mechanisms.

Another element worth noting is how CIs primarily focused on the rights dimension of the constitutional proposal. The expansion of rights was a defining feature of both constitutional drafts and reflects a broader global trend in constitutional development (Chilton and Versteeg Reference Chilton and Versteeg2020; Corvalán and Soto Reference Corvalán and Soto2021). A notable aspect of the CI model is its emphasis on placing citizens’ rights at the center of the constitution. Evidence suggests that increased public participation contributed to more expansive rights provisions by incorporating a broader range of individual interests and perspectives. As Landemore observes in discussing Iceland’s experience, opening the draft to public input raised concerns about minority rights. Advocacy groups could highlight how initial formulations by legislators or government representatives were less inclusive, bringing attention to issues that might otherwise have been overlooked (Landemore Reference Landemore2020a: 199).

From an institutional design perspective, a key lesson was the importance of including a clear mandate in the CI regulation for a third-party institution to design, coordinate and implement CIs. This approach was advantageous compared to the first process, where the constituent body had exclusive control over the CI process, as was the case with the Convention. Representatives may have had incentives to exclude citizen inputs from their work, given that CIs were formally treated as normative initiatives alongside proposals from representatives. In the second process, the Constitution explicitly required the University of Chile and the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile to jointly establish the SEPC as an ‘inter-institutional technical’ body, incorporating expertise from academic experts who had participated in the previous process. The continued use of UCampus for developing the digital platform was also crucial. The regulation permitted collaboration with other universities and civil society institutions, and ensured state funding and logistical support for the SEPC. This institutional design highlights the significant public role that universities played in the Chilean process, demonstrating their commitment not only to public participation but also to civic education and democratic engagement.

A compelling hypothesis worth exploring is that a more participatory constitutional process should result in a greater number of mechanisms for popular participation being included in the final constitutional proposal. In this sense, the value of CIs was evident in their incorporation into both constitutional drafts presented for referendum. During the 2021–2022 Constitutional Convention, several provisions involving CIs were integrated into the legislative process at both regional and national levels (Articles 156, 157 and 158), and CIs were also included in the constitutional reform procedure (Articles 385 and 386). In contrast, the 2023 Constitutional Council incorporated only one provision related to CIs in Chapter III, ‘Political Representation and Participation’ (Article 47).