Over the last 10 years, the Global Mental Health (GMH) movement has been engaged in concerted efforts to promote equitable access to mental health services for people worldwide. Commentators, such as Chowdhary et al. (Reference Chowdhary, Jotheeswaran, Nadkarni, Hollon, King, Jordans and Patel2014), have reflected on the importance of culturally and linguistically adapting mental health interventions to optimise engagement with services in local contexts. Researchers from diverse disciplinary fields (including anthropology, psychology and psychiatry) have also advocated for consideration of the local cultural and linguistic contexts when using standardised assessment measures (Mendenhall et al., Reference Mendenhall, Yarris and Kohrt2016). Nichter (Reference Nichter1981, Reference Nichter2010) introduced the term ‘idioms of distress’ to account for ‘socially and culturally resonant means of experiencing and expressing distress in local worlds’ (2010, p. 405). The DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) uses the term ‘cultural concepts of distress’ (CCDs; e.g. ataques de nervios, shenjing shuairuo, khyal cap) as an umbrella term that can be: (1) cultural syndromes, (2) cultural idioms of distress and/or (3) cultural explanations. Many of these documented terms can serve as some or all of these three subgroups of ‘CCDs’. For example ‘khyal cap’ is both an explanatory model – in that it may be perceived as the cause of a set of symptoms – and an idiom of distress – as it is a linguistic term used among particular groups to talk about suffering or distress. A review of epidemiological studies of CCDs by Kohrt et al. (Reference Kohrt, Rasmussen, Kaiser, Haroz, Maharjan, Mutamba, De Jong and Hinton2014) found that the terminology used to refer to locally distinct ways of expressing distress was not uniform across papers or research teams. Thus in the current paper, which seeks to examine linguistic idioms, the term ‘idioms/CCDs’ will be used to denote the range of linguistic terms that have been employed to date in an attempt to deal with the apparent ambiguity associated with these terms in the literature.

Mendenhall et al. (Reference Mendenhall, Yarris and Kohrt2016) showed that distress detected through narrative interviews can be missed by standardised scales, elucidating the need for more attention to be paid to the context of distress during assessment. While standardised assessment measures can help to facilitate international communication about distress that transcends cultural differences, local concepts of distress can make a rich contribution to the development of instruments and interventions that are valid in the local context (Mendenhall et al., Reference Mendenhall, Yarris and Kohrt2016). Kohrt & Hruschka (Reference Kohrt and Hruschka2010b) warn of the consequences of not addressing local psychological frameworks in treatment programmes, such as further pathologising and stigmatising the individual, particularly in the case of trauma healing.

Idioms/CCDs have been utilised in a number of ways in psychiatric research and practice, such as being incorporated into assessment questionnaires (Hinton et al., Reference Hinton, Reis and De Jong2015) or integrated into models accounting for the development of mental disorder [e.g. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and panic attacks] with the aim of improving the effectiveness of interventions among certain cultural groups (Hinton et al., Reference Hinton, Hofmann, Pitman, Pollack and Barlow2008). In terms of clinical use, idioms/CCDs can promote improved communication between patients and clinicians in the clinical encounter (Keys et al., Reference Keys, Kaiser, Kohrt, Khoury and Brewster2012); improve communication with clients and reduce stigma associated with distress in humanitarian situations (Kohrt & Hruschka, Reference Kohrt and Hruschka2010a); and improve the accuracy of assessments of psychosocial functioning or psychopathology (Hinton & Lewis-Fernández, Reference Hinton and Lewis-Fernández2010; Hinton et al., Reference Hinton, Kredlow, Bui, Pollack and Hofmann2012b).

The bulk of GMH-related research continues to be published in English-language journals. As such, research into idioms/CCDs frequently requires processes of translation and/or interpretation but also the negotiation of local and global epistemologies. To date, there has not been a systematic effort to identify and review the existing body of research that has sought to integrate information about idioms/CCDs into mental health assessment measures and/or interventions. The current systematic review sought to remedy this by conducting a narrative synthesis of relevant research studies. In addition, an adapted version of the COSMIN (COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health status Measurement Instruments) checklist (Mokkink et al., Reference Mokkink, Terwee, Knol, Stratford, Alonso, Patrick, Bouter and Vet2010) – originally developed to assess the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health-related patient reported outcomes – was used to assess the quality of the translation of local language descriptions of idiom/CCD data. The aim of this systematic review is to synthesise information relating to the integration of idioms/CCDs into interventions and/or assessment measures for distress. In particular, the review seeks to address the following questions:

(1) How was information about idioms/CCDs gathered?

(2) How was the information about the idioms/CCDs integrated into the assessment measure and/or intervention?

(3) How was the linguistic translation of idioms/CCDs handled?

(4) Did studies assess participants' level of understanding of the measure/intervention incorporating idioms/CCDs, and participants' perception of the relevance of the assessment/intervention (e.g. through piloting)?

(5) What were the psychometric properties of the assessment measures that were developed?

As a multitude of terms are used to denote idioms/CCDs, for this review they were defined as any distress concept (emotional, psychological, social, etc.) described in the terms used by the DSM (e.g. variations of: idioms of distress, CCDs, cultural syndrome, culturally bound explanatory model) or a distress concept that is described as being culturally influenced.

Method

The conduct and reporting of this systematic review was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, Grp and Group2009).

Protocol and registration

Systematic review methods and inclusion criteria were documented in a protocol consistent with the PRISMA-P guidelines, as recommended by Shamseer et al. (Reference Shamseer, Moher, Clarke, Ghersi, Liberati, Petticrew, Shekelle and Stewart2015). After initial screening, details of the review protocol were recorded on the PROSPERO (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/) database (registration number: CRD42017069244).

Eligibility criteria

Studies were deemed eligible if they:

(1) Contained primary data relating to a mental health assessment or intervention that incorporated information about an idiom/CCD

(2) The idioms/CCDs addressed were linguistic (i.e. expressed in the form of language rather than behaviour)

(3) Were available in English, French or Spanish

(4) Discussed how idioms/CCDs were incorporated into a psychosocial assessment measure or intervention

Information sources

The databases Scopus, PsychInfo, MEDLINE, Web of Science, Sociological Abstracts, CINAHL and ASSIA were searched with no time period limits. The databases were last searched on 19 October 2018. Databases were searched using terms relating to: idioms/CCDs such as ‘local concepts’; intervention and assessment such as ‘measurement’ and ‘treatment’; the CCDs listed by DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) e.g. ‘kufungisisa’; mental illness/health and linguistic/language-based terms such as ‘conceptual equivalence’. The full search strategy can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author. The reference lists of papers meeting inclusion criteria were hand-searched for other potentially eligible studies. Additionally an expert in the field was contacted for information on potentially eligible papers.

Study selection

The resulting papers were screened independently by two researchers (C.C. and B.K.). In order to establish coherence of understanding of the inclusion criteria, an initial sample of 10 studies was selected at random for the researchers to screen. They compared their results before carrying out independent screening of all articles. The researchers scanned the abstracts and titles before examining the resulting full texts for eligibility based on the pre-determined criteria. Any disparities between the researchers were resolved by thorough discussion of the inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Data collection process and data items

An extraction form was developed based on the research questions. Information was extracted by one researcher (C.C.) on the following aspects of each study:

(1) Aims of the study

(2) Population and location

(3) Methods of collection of information on idioms/CCDs

(4) Language the research was carried out in

(5) Terminology used by researcher(s) to refer to idioms/CCDs

(6) Methods/frameworks used to develop the assessment measure, or to integrate idioms/CCDs into existing assessment measures and/or psychosocial/psychological interventions

(7) Therapeutic models (e.g. cognitive behavioural therapy, interpersonal therapy) that guided the content of the interventions

(8) How translation was conducted (if applicable)

(9) Whether idioms/CCDs were compared with DSM/ICD categories

(10) Results of piloting/psychometric property testing

Assessing quality of translation and interpretation

The ‘cross-cultural validity evaluation’ section of the COSMIN checklist (Mokkink et al., Reference Mokkink, Terwee, Knol, Stratford, Alonso, Patrick, Bouter and Vet2010) was adapted for use in assessing the translation of idiom/CCD data in each paper. As these guidelines were developed for the translation of assessment measures, adjustments were made for the checklist to be used in relation to translation of idioms/CCDs alone. The COSMIN checklist entails choosing one of four response options regarding the level of quality specific to each item that corresponds to four possible gradings (excellent, good, fair and poor). Only fatal flaws are defined as poor quality to reflect the ‘worst score counts’ system of evaluation (Terwee et al., Reference Terwee, Mokkink, Knol, Ostelo, Bouter and De Vet2012). The full questions and response guidelines are available in a manual on the COSMIN website (http://www.cosmin.nl).

Results

Study selection

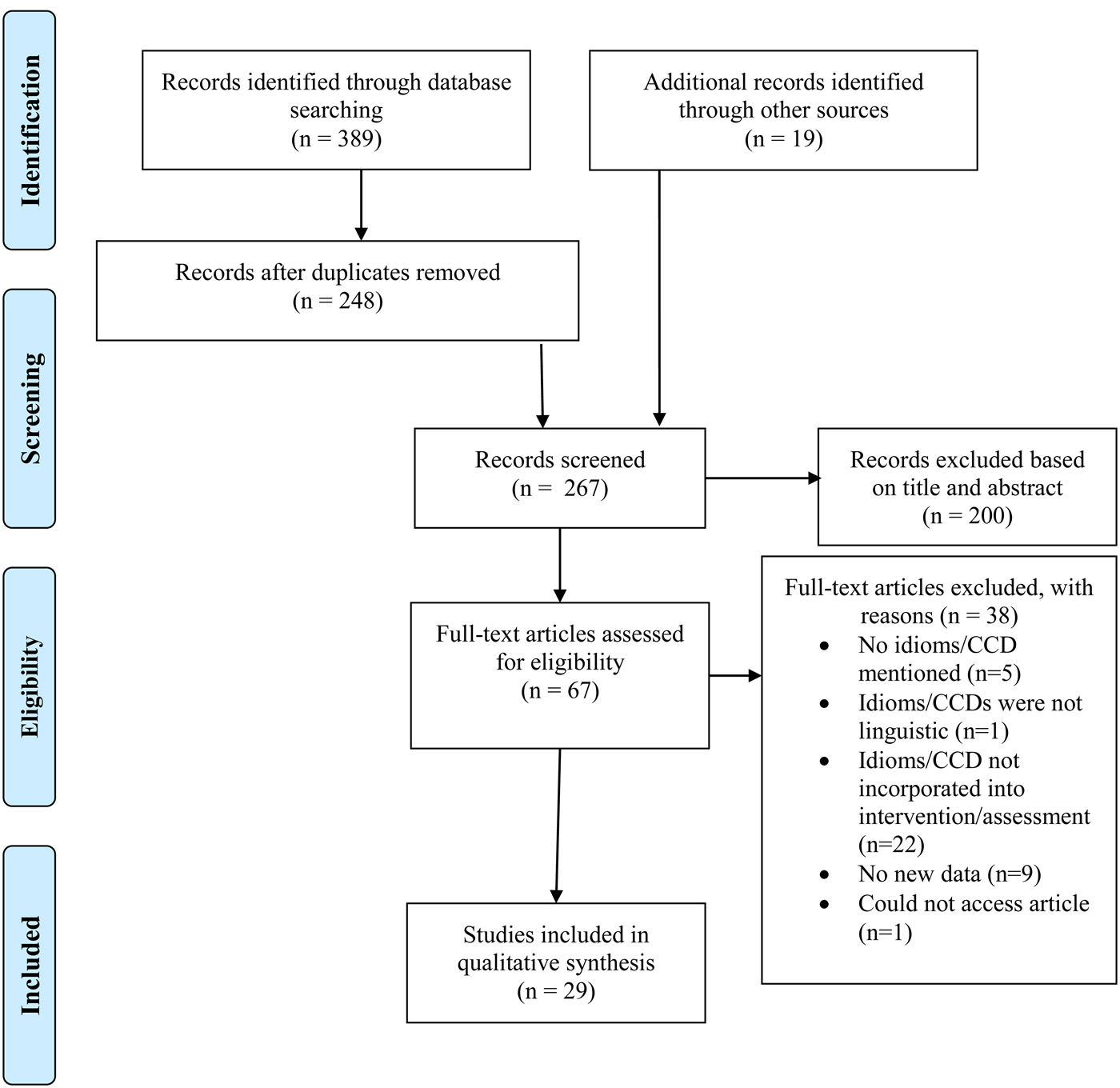

The PRISMA flowchart (see Fig. 1) provides information about the identification and selection of papers. After the full text review, one author (B.K.) included 14 papers that the primary author (C.C.) had not included because of a lack of consensus over the inclusion criterion pertaining to incorporating idioms/CCDs into an assessment/intervention. These differences were resolved after a thorough discussion about the inclusion criteria.

Fig. 1. PRISMA flowchart of studies through the screening.

Study characteristics

Characteristics of included studies are summarised in Table 1. The characteristics are described in the following section based on the 10 aspects extracted as outlined in the Method section. A number of papers discussed the development or use of the same assessment measure. Three discussed the Acholi Psychosocial Assessment Instrument (APAI) (Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, Bass, Betancourt, Speelman, Onyango, Clougherty, Neugebauer, Murray and Verdeli2007; Betancourt et al., Reference Betancourt, Bass, Borisova, Neugebauer, Speelman, Onyango and Bolton2009a; Mcmullen et al., Reference Mcmullen, O'callaghan, Richards, Eakin and Rafferty2012); two discussed different versions of the Cambodian Somatic Symptom and Syndrome Inventory (C-SSI) (Hinton et al., Reference Hinton, Hinton, Eng and Choung2012a, Reference Hinton, Kredlow, Pich, Bui and Hofmann2013); two discussed the Kreyòl Distress Idioms (KDI) inventory (Kaiser et al., Reference Kaiser, Kohrt, Keys, Khoury and Brewster2013, Reference Kaiser, Kohrt, Wagenaar, Kramer, Mclean, Hagaman, Khoury and Keys2015); two discussed the Afghanistan Symptom Checklist (ASCL) (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Omidian, Quraishy, Quraishy, Nasiry, Nasiry, Karyar and Yaqubi2006; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Ventevogel, Sancilio, Eggerman and Panter-Brick2014); and two discussed the ‘tension’ scale (Weaver & Hadley, Reference Weaver and Hadley2011; Weaver, Reference Weaver2017)

Table 1. Characteristics of the included studies

The studies were conducted in a wide range of locations, with three studies each from Uganda, India, USA and Haiti, two each from Afghanistan, Kenya and Sri Lanka and one each from Cambodia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Liberia, Vietnam, Tanzania, South Korea, Pakistan, Zimbabwe, Australia, Timor-Leste and Nepal. Four of the 29 studies were conducted with migrant populations in countries other than their country of origin (Phan et al., Reference Phan, Steel and Silove2004; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Han and Weed2006; Hinton et al., Reference Hinton, Hofmann, Rivera, Otto and Pollack2011, Reference Hinton, Kredlow, Pich, Bui and Hofmann2013).

Identification of idioms/CCDs

Identification of idioms/CCDs was described as being carried out in a number of ways: conducting qualitative interviews as part of the research activity reported in the papers (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Simunyu, Gwanzura, Lewis and Mann1997; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Omidian, Quraishy, Quraishy, Nasiry, Nasiry, Karyar and Yaqubi2006; Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, Bass, Betancourt, Speelman, Onyango, Clougherty, Neugebauer, Murray and Verdeli2007; Bass et al., Reference Bass, Ryder, Lammers, Mukaba and Bolton2008; Fernando, Reference Fernando2008; Kaaya et al., Reference Kaaya, Lee, Mbwambo, Smith-Fawzi and Leshabari2008; Silove et al., Reference Silove, Brooks, Bateman Steel, Steel, Hewage, Rodger and Soosay2009; Betancourt et al., Reference Betancourt, Bass, Borisova, Neugebauer, Speelman, Onyango and Bolton2009a; Mcmullen et al., Reference Mcmullen, O'callaghan, Richards, Eakin and Rafferty2012; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Ventevogel, Sancilio, Eggerman and Panter-Brick2014; Snodgrass et al., Reference Snodgrass, Lacy and Upadhyay2017; Green et al., Reference Green, Tuli, Kwobah, Menya, Chesire and Schmidt2018); utilising qualitative interview data from other research teams (Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Eustache, Raviola, Kaiser, Grelotti and Belkin2015); extracting data from clinical case notes (Mumford et al., Reference Mumford, Ayub, Karim, Izhar, Asif and Bavington2005; Abeyasinghe et al., Reference Abeyasinghe, Tennakoon and Rajapakse2012) and combined approaches such as reviewing relevant literature as well as gathering qualitative data (Phan et al., Reference Phan, Steel and Silove2004; Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Luitel, Acharya and Jordans2016); reviewing literature as well as using information from clinical experience (Hinton et al., Reference Hinton, Pollack, Weiss and Trung2018); participant observation, observant participation and qualitative interviews (Kaiser et al., Reference Kaiser, Kohrt, Keys, Khoury and Brewster2013, Reference Kaiser, Kohrt, Wagenaar, Kramer, Mclean, Hagaman, Khoury and Keys2015); and patient chart notes as well as qualitative interviews (Fabian et al., Reference Fabian, Fannoh, Washington, Geninyan, Nyachienga, Cyrus, Hallowanger, Beste, Rao and Wagenaar2018). Amongst the studies that used qualitative research methods, the most common ways of gathering information on idioms/CCDs were carrying out free-list interviews, focus groups and in-depth interviews with key informants. These activities were mainly carried out with community samples as opposed to patient samples. Two studies did not discuss how the idioms/CCDs were identified, as they were previously identified in the literature (Choi & Lee, Reference Choi and Lee2007; Hinton et al., Reference Hinton, Hofmann, Rivera, Otto and Pollack2011), while in one paper the methods used to identify idioms/CCDs were not described (Ice & Yogo, Reference Ice and Yogo2005). In two papers which described the development of the same assessment, a list of idioms/CCDs was developed by an expert in the field (Hinton et al., Reference Hinton, Hinton, Eng and Choung2012a, Reference Hinton, Kredlow, Pich, Bui and Hofmann2013). Additional information was gathered on previously identified idioms/CCDs in three studies, two by conducting qualitative research with the sample (Weaver & Hadley, Reference Weaver and Hadley2011; Weaver, Reference Weaver2017), and the other through rational selection from the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI-2) item pool (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Han and Weed2006).

Research language

The papers varied in how they dealt with the language in which the research was carried out. While one paper stated that research was carried out in participants' ‘first language’ (Fernando, Reference Fernando2008), it was not clear whether this was the case with other papers. Research was carried out: with participants who were ‘fluent in’ or ‘spoke the language’ used (Phan et al., Reference Phan, Steel and Silove2004; Abeyasinghe et al., Reference Abeyasinghe, Tennakoon and Rajapakse2012), in the ‘local language’ (Bass et al., Reference Bass, Ryder, Lammers, Mukaba and Bolton2008), in the language of the target ethnic group (Ice & Yogo, Reference Ice and Yogo2005; Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, Bass, Betancourt, Speelman, Onyango, Clougherty, Neugebauer, Murray and Verdeli2007; Betancourt et al., Reference Betancourt, Bass, Borisova, Neugebauer, Speelman, Onyango and Bolton2009a; Mcmullen et al., Reference Mcmullen, O'callaghan, Richards, Eakin and Rafferty2012); in the preferred language of communication (Hinton et al., Reference Hinton, Hofmann, Rivera, Otto and Pollack2011; Weaver & Hadley, Reference Weaver and Hadley2011; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Ventevogel, Sancilio, Eggerman and Panter-Brick2014; Weaver, Reference Weaver2017); the most widely spoken language (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Simunyu, Gwanzura, Lewis and Mann1997; Kaiser et al., Reference Kaiser, Kohrt, Keys, Khoury and Brewster2013, Reference Kaiser, Kohrt, Wagenaar, Kramer, Mclean, Hagaman, Khoury and Keys2015; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Eustache, Raviola, Kaiser, Grelotti and Belkin2015); the national language (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Han and Weed2006; Kaaya et al., Reference Kaaya, Lee, Mbwambo, Smith-Fawzi and Leshabari2008; Hinton et al., Reference Hinton, Hinton, Eng and Choung2012a, Reference Hinton, Kredlow, Pich, Bui and Hofmann2013, Reference Hinton, Pollack, Weiss and Trung2018; Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Luitel, Acharya and Jordans2016; Green et al., Reference Green, Tuli, Kwobah, Menya, Chesire and Schmidt2018) and the more common language in a multi-lingual context (Mumford et al., Reference Mumford, Ayub, Karim, Izhar, Asif and Bavington2005; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Omidian, Quraishy, Quraishy, Nasiry, Nasiry, Karyar and Yaqubi2006; Snodgrass et al., Reference Snodgrass, Lacy and Upadhyay2017; Fabian et al., Reference Fabian, Fannoh, Washington, Geninyan, Nyachienga, Cyrus, Hallowanger, Beste, Rao and Wagenaar2018). In two studies, there was no discussion of what language the research was carried out in (Choi & Lee, Reference Choi and Lee2007; Silove et al., Reference Silove, Brooks, Bateman Steel, Steel, Hewage, Rodger and Soosay2009).

Terminology used to capture idioms/CCDs

Up to 19 different terms were used to allude to the concept of idioms/CCDs, with no single term consistently used across papers and researchers. A range of different terms were employed by the studies to describe idioms/CCDs. Fourteen studies used the term ‘idiom(s) of distress’ (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Simunyu, Gwanzura, Lewis and Mann1997; Ice & Yogo, Reference Ice and Yogo2005; Mumford et al., Reference Mumford, Ayub, Karim, Izhar, Asif and Bavington2005; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Omidian, Quraishy, Quraishy, Nasiry, Nasiry, Karyar and Yaqubi2006; Hinton et al., Reference Hinton, Hofmann, Rivera, Otto and Pollack2011; Weaver & Hadley, Reference Weaver and Hadley2011; Kaiser et al., Reference Kaiser, Kohrt, Keys, Khoury and Brewster2013, Reference Kaiser, Kohrt, Wagenaar, Kramer, Mclean, Hagaman, Khoury and Keys2015; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Ventevogel, Sancilio, Eggerman and Panter-Brick2014; Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Luitel, Acharya and Jordans2016; Snodgrass et al., Reference Snodgrass, Lacy and Upadhyay2017; Weaver, Reference Weaver2017; Green et al., Reference Green, Tuli, Kwobah, Menya, Chesire and Schmidt2018; Fabian et al., Reference Fabian, Fannoh, Washington, Geninyan, Nyachienga, Cyrus, Hallowanger, Beste, Rao and Wagenaar2018); two studies used the term ‘local idioms of distress’ (Ice & Yogo, Reference Ice and Yogo2005; Mumford et al., Reference Mumford, Ayub, Karim, Izhar, Asif and Bavington2005); four studies used the term ‘local syndrome’ (Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, Bass, Betancourt, Speelman, Onyango, Clougherty, Neugebauer, Murray and Verdeli2007; Bass et al., Reference Bass, Ryder, Lammers, Mukaba and Bolton2008; Betancourt et al., Reference Betancourt, Bass, Borisova, Neugebauer, Speelman, Onyango and Bolton2009a; Mcmullen et al., Reference Mcmullen, O'callaghan, Richards, Eakin and Rafferty2012); and two studies used the term ‘culture-bound syndrome’ (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Han and Weed2006; Choi & Lee, Reference Choi and Lee2007). See Table 1 for full list of terms used across papers.

Integration of idioms/CCDs

Assessment measures

Sixteen studies discussed incorporating idioms/CCDs into the items of an assessment measure (including measures made up of a range of idioms). Most discussed developing novel assessments for the same cultural group from whom the idiom/CCDs data were gathered (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Simunyu, Gwanzura, Lewis and Mann1997; Phan et al., Reference Phan, Steel and Silove2004; Ice & Yogo, Reference Ice and Yogo2005; Mumford et al., Reference Mumford, Ayub, Karim, Izhar, Asif and Bavington2005; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Omidian, Quraishy, Quraishy, Nasiry, Nasiry, Karyar and Yaqubi2006; Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, Bass, Betancourt, Speelman, Onyango, Clougherty, Neugebauer, Murray and Verdeli2007; Fernando, Reference Fernando2008; Betancourt et al., Reference Betancourt, Bass, Borisova, Neugebauer, Speelman, Onyango and Bolton2009a; Abeyasinghe et al., Reference Abeyasinghe, Tennakoon and Rajapakse2012; Mcmullen et al., Reference Mcmullen, O'callaghan, Richards, Eakin and Rafferty2012; Hinton et al., Reference Hinton, Hinton, Eng and Choung2012a, Reference Hinton, Kredlow, Pich, Bui and Hofmann2013, Reference Hinton, Pollack, Weiss and Trung2018; Kaiser et al., Reference Kaiser, Kohrt, Keys, Khoury and Brewster2013, Reference Kaiser, Kohrt, Wagenaar, Kramer, Mclean, Hagaman, Khoury and Keys2015; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Ventevogel, Sancilio, Eggerman and Panter-Brick2014; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Eustache, Raviola, Kaiser, Grelotti and Belkin2015; Snodgrass et al., Reference Snodgrass, Lacy and Upadhyay2017; Fabian et al., Reference Fabian, Fannoh, Washington, Geninyan, Nyachienga, Cyrus, Hallowanger, Beste, Rao and Wagenaar2018); while five discussed the use of idioms/CCDs in the adaptation of pre-existing instruments created elsewhere (Bass et al., Reference Bass, Ryder, Lammers, Mukaba and Bolton2008; Kaaya et al., Reference Kaaya, Lee, Mbwambo, Smith-Fawzi and Leshabari2008; Silove et al., Reference Silove, Brooks, Bateman Steel, Steel, Hewage, Rodger and Soosay2009; Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Luitel, Acharya and Jordans2016; Green et al., Reference Green, Tuli, Kwobah, Menya, Chesire and Schmidt2018). Three studies described the development of a checklist or scale for assessing levels of symptoms of a particular idiom/CCD previously identified in the literature: Weaver & Hadley (Reference Weaver and Hadley2011) and Weaver (Reference Weaver2017) describe the development of an original checklist within the target population; and Roberts et al. (Reference Roberts, Han and Weed2006) adapted a scale previously created elsewhere for this purpose.

Interventions

Two studies discussed the use of idioms/CCDs in an intervention. One discussed the incorporation of idioms/CCDs into an intervention using a cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) framework (Hinton et al., Reference Hinton, Hofmann, Rivera, Otto and Pollack2011) through specifically addressing nervios and ataque de nervios during sessions on modifying catastrophic cognitions. The other utilised a programme of music therapy, drama and group therapy based on Hahn-puri, or processes that help to vent Hahn (sorrow/regret) a concept closely related to Hwa-Byung (Choi & Lee, Reference Choi and Lee2007).

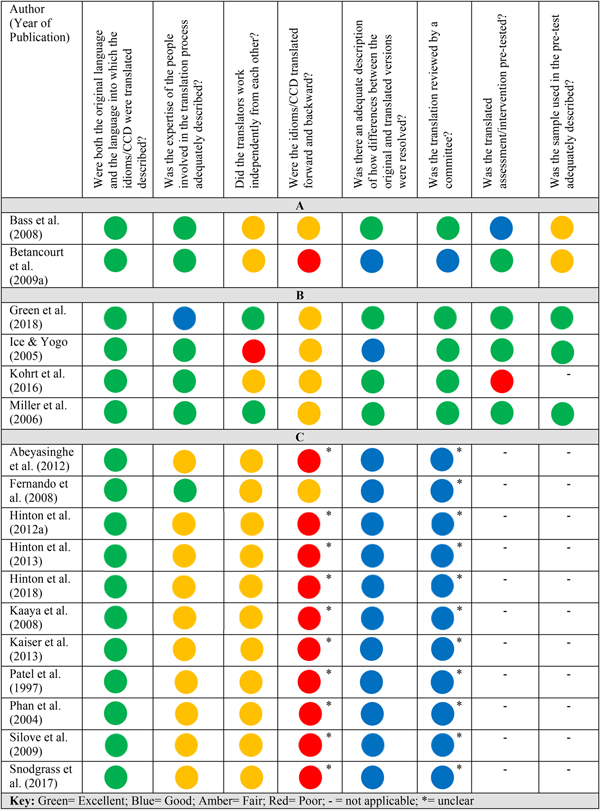

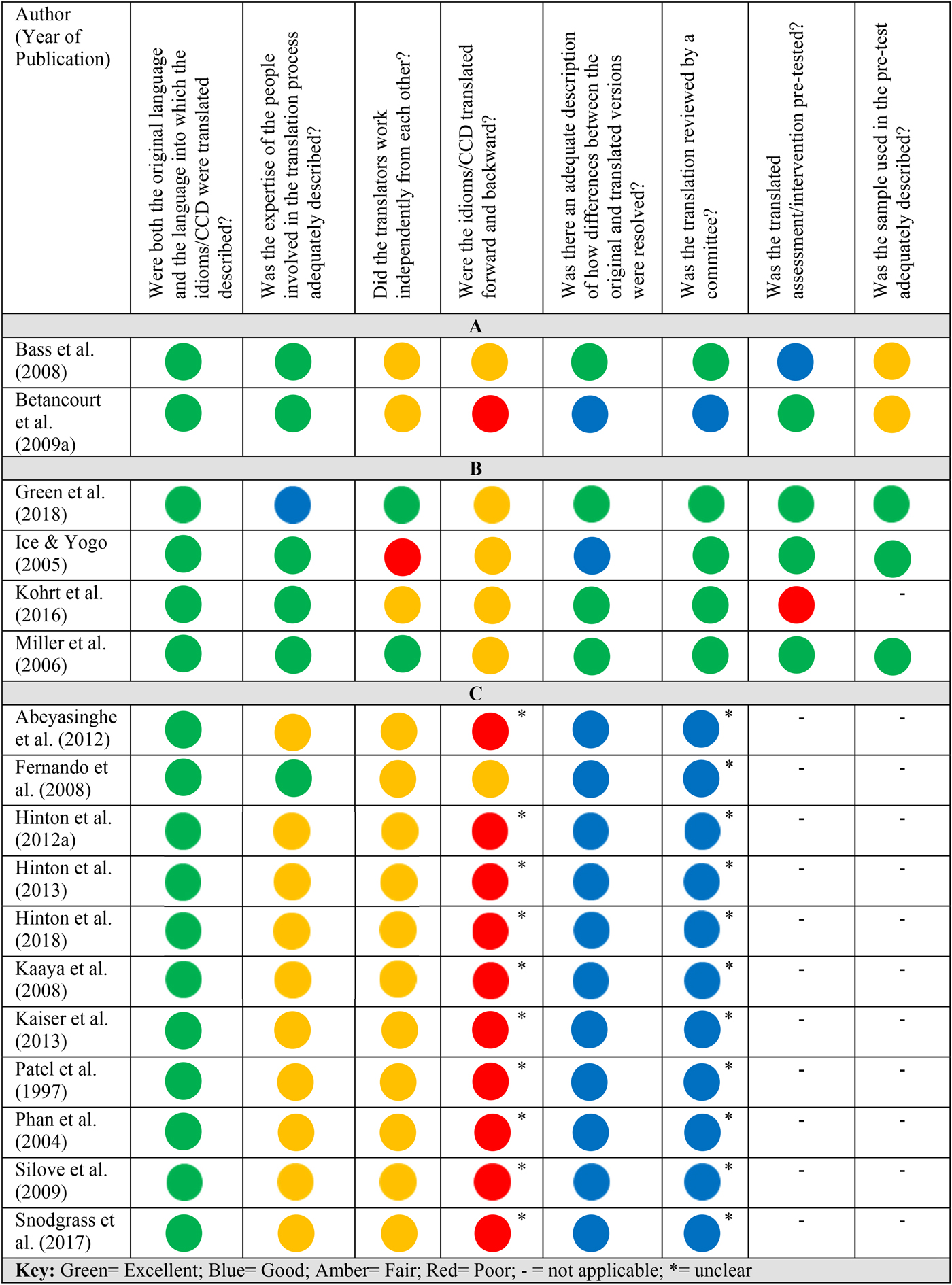

Translation: COSMIN checklist

The adapted COSMIN checklist was used to assess the quality of the translation of idiom/CCD data in each paper. Four papers neither discussed translation processes of the idiom data, nor referred the reader to another paper that did (Mumford et al., Reference Mumford, Ayub, Karim, Izhar, Asif and Bavington2005; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Han and Weed2006; Choi & Lee, Reference Choi and Lee2007; Hinton et al., Reference Hinton, Hofmann, Rivera, Otto and Pollack2011). However, in all of these, translation of idiom/CCD terms did not occur during the conduct of the research and only occurred for the purpose of writing the paper in English. In two studies, the idiom/CCD (‘tension') was described in terms of how it is used and applied in the local context and thus translation did not occur (Weaver & Hadley, Reference Weaver and Hadley2011; Weaver, Reference Weaver2017). One study was carried out in English (Fabian et al., Reference Fabian, Fannoh, Washington, Geninyan, Nyachienga, Cyrus, Hallowanger, Beste, Rao and Wagenaar2018). Five papers referred the reader to other included papers that discussed the translation of idiom/CCD data (Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, Bass, Betancourt, Speelman, Onyango, Clougherty, Neugebauer, Murray and Verdeli2007; Mcmullen et al., Reference Mcmullen, O'callaghan, Richards, Eakin and Rafferty2012; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Ventevogel, Sancilio, Eggerman and Panter-Brick2014; Kaiser et al., Reference Kaiser, Kohrt, Wagenaar, Kramer, Mclean, Hagaman, Khoury and Keys2015; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Eustache, Raviola, Kaiser, Grelotti and Belkin2015). Seventeen papers included in the current review provided information about the translation of idiom/CCD data into English (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. COSMIN evaluation of translation of idioms/CCDs.

In Fig. 2 the papers are grouped according to whether the linguistic translation of the idiom/CCD occurred: (A) before the assessment items/intervention content were generated [e.g. in Bass et al. (Reference Bass, Ryder, Lammers, Mukaba and Bolton2008), interviewers translated the qualitative interview data from Lingala into French straight after collecting the data]; (B) after the assessment items/intervention content were generated to check the appropriateness of the measure [e.g. in Kohrt et al. (Reference Kohrt, Luitel, Acharya and Jordans2016) a translation of a previously developed instrument was back-translated after the addition of idioms to check its accuracy] and (C) only for the purpose of writing the paper which was published in another language [e.g. in Abeyasinghe et al. (Reference Abeyasinghe, Tennakoon and Rajapakse2012) the measure development was carried out in Sinhalese, but some idioms are translated and explained for the reader of the article, which is written in English]. It was not appropriate to complete the final two questions on the adapted COSMIN checklist (which pertain to the piloting of a translated assessment measure) for studies in category (C), as translation in these studies only occurred for the purposes of the write-up. The COSMIN checklist works by assigning a rating (excellent, good, fair or poor) partly according to how essential an item is to ensure quality of translation. Therefore some items for some studies may be marked in blue for ‘good’ even if the information for that item was not provided, as it is not deemed to be a fatal flaw.

All papers that discussed the issue of language sufficiently described both the original language and the language into which the idioms/CCDs were being translated. In all studies in categories (A) and (B), the expertise of the translators was adequately described. In papers in category (C), all except for one (Fernando, Reference Fernando2008) did not describe the expertise of the translators. In all papers except for two (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Omidian, Quraishy, Quraishy, Nasiry, Nasiry, Karyar and Yaqubi2006; Green et al., Reference Green, Tuli, Kwobah, Menya, Chesire and Schmidt2018), translators either did not work independently from each other, or it was unclear whether or not they did so. To receive an ‘excellent’ rating on backward and forward translation processes, papers were required to indicate that multiple forward and multiple backward translations were undertaken however, papers variously indicated one forward and one backward translation; only a forward translation; or failed to clearly indicate how it was done. As such, no papers received an ‘excellent’ rating on this section. Four papers adequately described how differences in translations between translators were resolved (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Omidian, Quraishy, Quraishy, Nasiry, Nasiry, Karyar and Yaqubi2006; Bass et al., Reference Bass, Ryder, Lammers, Mukaba and Bolton2008; Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Luitel, Acharya and Jordans2016; Green et al., Reference Green, Tuli, Kwobah, Menya, Chesire and Schmidt2018), while all remaining papers either described these processes poorly or not at all. In a similar number of studies, the translated idioms/CCDs were reviewed by a committee (Ice & Yogo, Reference Ice and Yogo2005; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Omidian, Quraishy, Quraishy, Nasiry, Nasiry, Karyar and Yaqubi2006; Bass et al., Reference Bass, Ryder, Lammers, Mukaba and Bolton2008; Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Luitel, Acharya and Jordans2016; Green et al., Reference Green, Tuli, Kwobah, Menya, Chesire and Schmidt2018), while in all others there was no review.

Regarding the adapted COSMIN criteria relating to pre-testing assessment measures containing idioms/CCDs, four of the six studies to which this question was relevant pre-tested the measure in the targeted population (Ice & Yogo, Reference Ice and Yogo2005; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Omidian, Quraishy, Quraishy, Nasiry, Nasiry, Karyar and Yaqubi2006; Betancourt et al., Reference Betancourt, Bass, Borisova, Neugebauer, Speelman, Onyango and Bolton2009a; Green et al., Reference Green, Tuli, Kwobah, Menya, Chesire and Schmidt2018); in one study the measure was pre-tested, but it was unclear whether this was carried out in the target population (Bass et al., Reference Bass, Ryder, Lammers, Mukaba and Bolton2008); while in another study the assessment measure was not pre-tested because the paper was reporting on the development of the measure itself (Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Luitel, Acharya and Jordans2016). Of the five studies that carried out pre-testing, three adequately described the sample used (Ice & Yogo, Reference Ice and Yogo2005; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Omidian, Quraishy, Quraishy, Nasiry, Nasiry, Karyar and Yaqubi2006; Green et al., Reference Green, Tuli, Kwobah, Menya, Chesire and Schmidt2018), while the other two did not (Bass et al., Reference Bass, Ryder, Lammers, Mukaba and Bolton2008; Betancourt et al., Reference Betancourt, Bass, Borisova, Neugebauer, Speelman, Onyango and Bolton2009a). Studies in category (C) had poorer quality translation processes than those in categories (A) and (B), with only one paper receiving an ‘excellent’ rating in more than one category (Fernando, Reference Fernando2008).

Comparisons with psychiatric diagnoses (DSM/ICD)

Seven studies drew parallels between idioms/CCDs and DSM categories such as: using the idioms/CCDs to contribute to a scale for detecting DSM/ICD psychiatric disorders (Mumford et al., Reference Mumford, Ayub, Karim, Izhar, Asif and Bavington2005; Abeyasinghe et al., Reference Abeyasinghe, Tennakoon and Rajapakse2012; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Eustache, Raviola, Kaiser, Grelotti and Belkin2015; Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Luitel, Acharya and Jordans2016; Green et al., Reference Green, Tuli, Kwobah, Menya, Chesire and Schmidt2018); describing them as closely approximating DSM categories (Bass et al., Reference Bass, Ryder, Lammers, Mukaba and Bolton2008); and describing the locally identified problems as containing varying combinations of DSM-IV symptoms of depression and related symptoms (Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, Bass, Betancourt, Speelman, Onyango, Clougherty, Neugebauer, Murray and Verdeli2007).

In seven studies, comparisons were made between idioms/CCDs and more general psychiatric constructs as opposed to comparing them with specific diagnoses listed in the manuals, i.e. describing idiom/CCDs as: ‘depression-like’ (Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, Bass, Betancourt, Speelman, Onyango, Clougherty, Neugebauer, Murray and Verdeli2007; Betancourt et al., Reference Betancourt, Bass, Borisova, Neugebauer, Speelman, Onyango and Bolton2009a; Mcmullen et al., Reference Mcmullen, O'callaghan, Richards, Eakin and Rafferty2012); conceptually similar to psychiatric constructs (Kaiser et al., Reference Kaiser, Kohrt, Wagenaar, Kramer, Mclean, Hagaman, Khoury and Keys2015); being representative of a number of psychiatric constructs (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Han and Weed2006); as idioms for depressive or anxiety symptoms (Kaaya et al., Reference Kaaya, Lee, Mbwambo, Smith-Fawzi and Leshabari2008); or grouped idiom/CCD data according to psychiatric constructs (Phan et al., Reference Phan, Steel and Silove2004). These comparisons are summarised in Table 1.

Efficacy, acceptability and psychometric properties

Assessments

All studies that discussed the incorporation of idioms/CCDs into assessment measures sought feedback from relevant stakeholders by piloting the assessment measures prior to use, carrying out focus group discussions during development, or conducting qualitative interventions on the suitability of the language used.

A number of studies included in the review investigated the psychometric properties of the measures that incorporated the idioms/CCDs, including assessing internal, inter-rater and test–retest reliability and content, convergent, discriminant and construct validityFootnote †Footnote 1. These findings are summarised in Table 2. The majority of studies reported that assessment measures had good psychometric properties. The following studies reported assessment measures that had inadequate psychometric properties: Betancourt et al. (Reference Betancourt, Bass, Borisova, Neugebauer, Speelman, Onyango and Bolton2009a) reported that the conduct, anxiety and prosocial scales of the Acholi Psychosocial Assessment Instrument (APAI) demonstrated inadequate levels of reliability and validity; in Bass et al. (Reference Bass, Ryder, Lammers, Mukaba and Bolton2008), the adapted Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL) and Edinburgh Post-Natal Depression Scale (EPDS) demonstrated only adequate test–retest reliability; in Ice & Yogo (Reference Ice and Yogo2005), factor analysis showed that the Luo Perceived Stress Scale (LPSS) did not demonstrate a uni-factorial structure; in Mumford et al. (Reference Mumford, Ayub, Karim, Izhar, Asif and Bavington2005), specificity of the ‘D’ (depression) scale in a sample of depressive v. anxiety patients was not high (64%); in Rasmussen et al. (Reference Rasmussen, Eustache, Raviola, Kaiser, Grelotti and Belkin2015) the Zanmi Lasante Depression Symptom Inventory (ZLDSI) had acceptable sensitivity but did less well with specificity, which could not be improved without unacceptable losses in sensitivity.

Table 2. Psychometric properties of assessments

Interventions

In the two studies that examined an intervention that incorporated the use of idioms/CCDs, the intervention produced significantly better outcomes than the control conditions (Choi & Lee, Reference Choi and Lee2007; Hinton et al., Reference Hinton, Hofmann, Rivera, Otto and Pollack2011); however, determining whether the incorporation of idioms/CCDs was a factor in the effectiveness of the intervention was not a specific aim of the studies, so we are not able to evaluate what intervention effects are due to idioms/CCDs. The study by Hinton et al. (Reference Hinton, Hofmann, Rivera, Otto and Pollack2011) was a pilot study comparing an intervention that incorporated the use of idioms/CCDs into a culturally adapted CBT (CA-CBT) for Latina women with treatment-resistant PTSD and compared this intervention with applied muscle relaxation. No information about the perceived acceptability of the intervention was provided in the study. The study by Choi & Lee (Reference Choi and Lee2007) integrated information about the idiom/CCDs into a culturally tailored nursing programme. The study did not discuss initial piloting or recipients' perceptions of the acceptability of the intervention.

Discussion

The current review gathers together, for the first time, research papers that discuss the integration of idioms/CCDs into psychological/psychosocial assessment measures and interventions. The review aimed to synthesise information on how idiom/CCD data were gathered, how their integration occurred, whether appropriate translation procedures were adhered to and the acceptability of these assessment measures/interventions.

In terms of the methods used to identify idioms/CCDs (review question 1), primary qualitative research was the most commonly used method. The justification for the choice of study language varied across the studies. In two studies, research was carried out in the preferred language of participants (Weaver & Hadley, Reference Weaver and Hadley2011; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Ventevogel, Sancilio, Eggerman and Panter-Brick2014); in three studies it was carried out in the official language of the country where research was undertaken (Hinton et al., Reference Hinton, Hofmann, Rivera, Otto and Pollack2011; Kaiser et al., Reference Kaiser, Kohrt, Keys, Khoury and Brewster2013, Reference Kaiser, Kohrt, Wagenaar, Kramer, Mclean, Hagaman, Khoury and Keys2015) and all other studies chose one language from a range of languages spoken in a setting where the research was conducted. This monolingual approach to working can belie the multilingual realities of people's daily lives where a number of languages can be in play (Andrews et al., Reference Andrews, Fay, White, Choi, Ollerhead and French2018). The practicalities of research mean that linguistic diversity can be difficult to accommodate; however, the marginalisation of particular languages and the risks that this may pose for certain communities needs to be recognised.

Regarding the integration of idioms/CCDs into assessments and interventions (review question 2), new assessment measures were developed by creating items based on signs and symptoms identified in qualitative interviews. For studies that created local assessment measures for constructs that had been identified elsewhere like depression or anger attacks, they either created new scales (Mumford et al., Reference Mumford, Ayub, Karim, Izhar, Asif and Bavington2005; Abeyasinghe et al., Reference Abeyasinghe, Tennakoon and Rajapakse2012); adapted a pre-existing scale using the locally identified symptoms (Silove et al., Reference Silove, Brooks, Bateman Steel, Steel, Hewage, Rodger and Soosay2009; Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Luitel, Acharya and Jordans2016); or used a combination of pre-existing and new scales (Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Eustache, Raviola, Kaiser, Grelotti and Belkin2015). In terms of interventions, idioms/CCDs were incorporated into CBT (Hinton et al., Reference Hinton, Hofmann, Rivera, Otto and Pollack2011) or a mix of music therapy, drama and group therapy (Choi & Lee, Reference Choi and Lee2007).

Regarding translation processes (review question 3), some papers did not sufficiently discuss translation, with six studies failing to detail translation processes of idiom/CCD terms (Mumford et al., Reference Mumford, Ayub, Karim, Izhar, Asif and Bavington2005; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Han and Weed2006; Choi & Lee, Reference Choi and Lee2007; Silove et al., Reference Silove, Brooks, Bateman Steel, Steel, Hewage, Rodger and Soosay2009; Hinton et al., Reference Hinton, Hofmann, Rivera, Otto and Pollack2011), perhaps due to the fact that translation only occurred after the research process was completed for the purposes of publishing the paper in an academic journal. Of the studies that did describe translation processes, all studies except for one (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Omidian, Quraishy, Quraishy, Nasiry, Nasiry, Karyar and Yaqubi2006) were graded ‘unclear’ or ‘inadequately described’ for at least one question out of eight in the COSMIN assessment. Twelve studies in this review compared idioms/CCDs with psychiatric constructs in some way. White et al. (Reference White, Fay, Phipps, Giurgi-Oncu and Chiumentoin press) have raised concerns about the risk of epistemic injustice occurring when indigenous knowledge is subsumed into constructs developed in the Global NorthFootnote 2. It is also important that translation of information gathered on idioms/CCDs is conducted in a systematic and reflective manner, even if the translation only occurs after the research has been carried out for the purposes of the paper. With this in mind, White et al. (Reference White, Fay, Phipps, Giurgi-Oncu and Chiumentoin press) have constructed a Group Reflection Tool that can be used following communications about distress and/or wellbeing that have involved an interpreter. As one example of these types of comparisons, Abeyasinghe et al. (2012) created a symptom scale of locally identified idioms of distress and other ‘universal terms’ that correlated with the diagnosis of depression in the DSM. They concluded that, ‘only certain idioms of distress are useful in detecting pathological states such as depression’ (p. 147). In such circumstances, it is important to be aware of the risk of category fallacy (Kleinman, Reference Kleinman1977) as the authors are noting associations between local idioms and the depression construct and subsequently describing those local idioms as symptoms of depression. This neglects the possibility that locally identified idioms may be useful in detecting culturally specific pathological states. On the other hand, Fernando (Reference Fernando2008) appeared to deal with translation and sensitivity to semantic equivalence well. The emic-etic dilemma experienced by the author in attempting to give English language terms to the factors of the scale was discussed, and it was noted that certain terms could not easily be translated into diagnoses developed in the Global North without losing meaning.

With regard to review questions 4 and 5, all studies assessed the participants' level of understanding of the measures incorporating idioms/CCDs either during testing or through prior piloting. The majority of studies reported that these assessment measures had good psychometric properties. The most commonly reported psychometric property was internal consistency, with all of these assessment measures showing good or high internal consistency. A range of different approaches was used across the studies to determine the validity of the measures that incorporated idioms/CCDs, and the majority was shown to have moderate to high levels of validity. One study (Phan et al., Reference Phan, Steel and Silove2004) gathered participants' views on the cultural sensitivity of a measure that incorporates idioms/CCDs, in comparison with standard measures. This is an important gauge of the acceptability of a measure, and researchers should explicitly gather this information in future. It is important to note however that this review does not cover all of the studies that have carried out psychometric testing of assessment measures that included idioms/CCDs, as only studies that reported on development and testing of scales were included.

None of the studies included in this review reported on efforts to incorporate idioms/CCDs into assessment measures/interventions that were intended for majority populations living in the Global North. This conveys a potential lack of parity in mental health research where idiomatic blind-spots (i.e. an obscuring of the culturally situated nature of one's own distress) may be occurring in the Global North. This is consistent with the previously noted observation that none of the CCDs listed in the glossary of the DSM-5 are English language terms, and none are deemed to originate in North America or Europe. These descriptions of idioms/CCDs do not form part of the taxonomy of mental illness in the main text but are instead restricted to the appendix (Thornton, Reference Thornton, White, Jain, Orr and Read2017). Consistent with views previously expressed by commentators (Kleinman, Reference Kleinman1977), it seems that there is an assumption that the largely English language terminology used to describe ‘mental disorders’ in the Global North are capturing experiences that are not culturally constructed but are instead universal forms of mental illnesses that are not prone to cultural particularity. This can create circumstances where non-English language terms for distress are bench-marked against, or indeed subsumed by, psychiatric terminology on the grounds that the latter carries greater legitimacy. This is a particular risk when local language terminology is translated into English and ‘conceptual equivalence’ is deployed (see White et al., Reference White, Fay, Phipps, Giurgi-Oncu and Chiumentoin press). It is thus important to raise awareness among mental health practitioners and researchers of the potential benefits of sharing knowledge about perceptions of distress and/or wellbeing in diverse linguistic and cultural settings, and of avoiding the imposition of concepts that are commonplace in majority languages like English.

The majority of included studies addressed assessment measures. However, the two studies that integrated idioms/CCDs into interventions produced better outcomes when incorporating idioms into an intervention compared with the standard intervention. Thus there is potential for future research to further explore the use of idioms/CCDs in mental health interventions. A number of approaches have been proposed for adapting and translating interventions and assessments for local contexts, e.g. the Design, Implementation, Monitoring and Evaluation (DIME) (Applied Mental Health Research Group, 2013), a ‘culturally sensitive framework’ (Bernal & Sáez-Santiago, Reference Bernal and Sáez-Santiago2006) and the translation monitoring form (Van Ommeren et al., Reference Van Ommeren, Sharma, Thapa, Makaju, Prasain, Bhattarai and De Jong1999).

Limitations

The current review had a number of limitations. First, the terminology used to refer to idioms/CCDs varied greatly between papers and included many different terms. This is similar to what Kohrt et al. (Reference Kohrt, Rasmussen, Kaiser, Haroz, Maharjan, Mutamba, De Jong and Hinton2014) found in their systematic review of CCDs – that the terminology used to refer to locally distinct ways of expressing distress (idioms, CCDs etc.) was not uniform across papers or research teams. The wide variety of terms and phrases used may be one reason that a substantial number of papers included in this review were found from searching reference lists, as it is possible that the search terms were not exhaustive enough. This is a difficulty inherent in conducting a review in an evolving area of study and practice: the concept being explored in this review is relatively new, and no papers before 1997 met the inclusion criteria. Moving forward, it will be important to ensure that researchers investigating linguistic expressions of distress that are specific to particular localities and cultural groups use the terminology ‘idioms/CCDs’ to refer to these phenomena.

The authors recognise the important role of ethnographic research methods for examining the utility and validity of idioms/CCDs in assessments and interventions. However it was beyond the scope of the current review to conduct a thorough examination of the ethnographic methods employed across the studies, which is a potential limitation of this review. A further potential limitation of the current review is that it included only published articles and the included papers were selected according to the parameters of our inclusion criteria. Thus, many studies relevant to this topic of idioms/CCDs were not included.

A final limitation relates to the fact that the scope of the current review was specifically limited to the linguistic translation of narrative descriptions of idioms/CCDs. A key focus was the attention allocated to processes of translation when integrating idioms/CCDs into assessment measures and interventions, however it should be noted that cross cultural mental health related work may well involve working with idioms that are ‘untranslatable’ (Kirmayer & Swartz, Reference Kirmayer, Swartz, Patel, Minas, Cohen and Prince2013). In other words, irrespective of how much care and attention is allocated to processes of forward- and backward-translation, the sharing of concepts relating to mental health across languages may continue to prove challenging. There is a need for further research, and synthesis of this research, relating to: (1) the methods used to collect information about idioms/CCDs – including ethnographic research methods; (2) how the idioms/CCDs were contextualised in terms of local meaning – including how consistent the operationalisation of the idioms/CCDs was with local ethnopsychology and (3) reflections from stakeholders about the clinical utility of the idioms/CCDs in the assessed studies.

Conclusion

We advocate for the integration of idioms/CCDs into assessment measures and interventions to increase understanding of forms of suffering, improve clinical communication and treatment outcomes, and reduce stigma (Kaiser et al., Reference Kaiser, Kohrt, Wagenaar, Kramer, Mclean, Hagaman, Khoury and Keys2015). The studies included in the review demonstrate the efforts that some researchers have made to integrate local ways of understanding and expressing distress into GMH assessment measures and interventions. A key finding was that a large proportion of studies did not engage in particularly rigorous forward- and backward-linguistic translation procedures. In addition, there was a tendency for idioms/CCDs to be integrated into existing assessment measures that had been developed in the Global North. Further research is needed reporting on the emic/bottom-up development of assessment measures developed in local contexts of the Global South. This is in keeping with calls for more equitable exchanges of knowledge about mental health and wellbeing between the Global North and the Global South (White et al., Reference White, Jain and Giurgi-Oncu2014).

Acknowledgements

The involvement of authors C.C. and R.W. in this research paper was supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council – ‘Idioms of Distress, Resilience, and Wellbeing: Enhancing understanding about mental health in multilingual contexts’ (AH/P009786/1): Nov 2016 – Feb 2018 (http://gtr.rcuk.ac.uk/projects?ref=AH%2FP009786%2F1).

Author contributions

C.C. contributed to the conception and design of the systematic review; the identification, screening and synthesis of relevant literature; and the drafting and revising of the manuscript. R.W. contributed to the conception and design of the systematic review, the synthesis of relevant literature, and the drafting and revising of the manuscript. B.K. contributed to the screening and synthesis of relevant literature, and the revising of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of this article.

Financial support

B.K.'s involvement in this research paper was supported by an NRSA grant from the National Institutes of Mental Health (MH113288).

Declaration of interest

None.