1. The emergence of a paradigm

The last decades have seen unprecedented changes to the Earth's biological and cultural components. From genes, species, ecosystems, landscapes and seascapes, to languages, practices, traditions, artistic expressions and belief, value, and knowledge systems, these diversities are facing rapid changes and, most importantly, rapid loss (Barnosky et al., Reference Barnosky, Matzke, Tomiya, Wogan, Swartz, Quental and Ferrer2011; Harmon & Loh, Reference Harmon and Loh2010; Maffi, Reference Maffi2005). Although the loss of biocultural diversity is usually associated with local effects on social-ecological systems, it is less clear how this loss could impact global sustainability. Important efforts to understand nature-culture relations and bolster sustainable practices at all scales have been made by scientists, local communities, civil society organizations and policy makers. In spite of their efforts, a stronger articulation between sectors and biocultural discourses is needed for a broader transformative impact. Here, we discuss how biocultural approaches, collectively referred to as the biocultural paradigm, can contribute to both local and global sustainability. Moreover, we analyse some of the main connections between the most prominent biocultural discourses in the context of sustainability. Finally, in order to encourage a greater articulation between science, practice and policy, we propose that discourses produced within the biocultural paradigm should integrate ontological, epistemic and ethico-political dimensions.

The term ‘paradigm’ is employed here to designate a common thinking field (shared forms of understanding, values and methods), which suggests ‘new puzzles’ and new approaches to solving them (Kuhn, Reference Kuhn1970). In this sense, the ‘biocultural paradigm’, as termed by Maffi (Reference Maffi, Pretty, Ball, Benton, Guivant, Lee, Orr and Ward2007) and Toledo (Reference Toledo2013), corresponds to a wide-ranging framework that poses novel questions and methodologies around the intricate connections between nature and culture. In its early version, the biocultural paradigm was deeply seated in the concept of biocultural diversity (Maffi, Reference Maffi, Pretty, Ball, Benton, Guivant, Lee, Orr and Ward2007), which arose in the 1990s to denote the inextricable link between areas of high biological and cultural diversity (Maffi & Woodley, Reference Maffi and Woodley2012; Posey, Reference Posey and Posey1999). Spurring early discussions, the Declaration of Belém (1988) raised alarm over the rapid decline in biological and cultural diversity and recognized the dependence of people on natural resources (Rapport & Maffi, Reference Rapport, Maffi, Pilgrim and Pretty2010). It also emphasized the importance of native people as stewards of the world's biodiversity (including genetic resources and the knowledge to manage them), and the inextricable links between all manifestations of life (biological, cultural and linguistic) (Maffi & Woodley, Reference Maffi and Woodley2012; Posey, Reference Posey and Posey1999). This declaration gave recognition and value to indigenous knowledge, including local indigenous specialists as authorities that need to be consulted in programs affecting indigenous communities, their resources and their environments. These ideas gained prominence in response to concerns about the rapid decline of biocultural diversity and the loss of intergenerational transmission of traditional knowledge, practices and languages (Maffi, Reference Maffi2005; Maffi & Woodley, Reference Maffi and Woodley2012; Posey, Reference Posey and Posey1999), as evidenced in the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD; United Nations, 1992), and highlighted again in the 2010 Declaration on Bio-Cultural Diversity (United Nations, 2010).

Recognition of indigenous communities and their knowledge has been growing in the last three decades. Calls have been made for sustainable development approaches to be aligned with local cultural practices and for such communities to have greater control over their land, development and heritage (Brondizio & Tourneau, Reference Brondizio and Tourneau2016; Davidson-Hunt et al., Reference Davidson-Hunt, Turner, Te Pareake Mead, Cabrera-Lopez, Bolton, Idrobo and Robson2012; Garnett et al., Reference Garnett, Burgess, Fa, Fernández-Llamazares, Molnár, Robinson and Leiper2018; Sterling et al., Reference Sterling, Filardi, Toomey, Sigouin, Betley, Gazit and Bergamini2017). In 2018, marking the 30th anniversary of the Declaration of Belém, this city hosted again a large international meeting to discuss the rights of indigenous peoples and traditional populations and the sustainable use of biodiversity (www.ise2018belem.com). Attracting over 1600 participants from 45 countries, of whom 500 were indigenous, this event has been by far the largest gathering to date of researchers, scholars, students, indigenous peoples and other traditional communities, government agencies, civil society organizations, and social movements engaged in these discussions. The magnitude and resolutions of this event highlight the currency of these discussions and the crucial role of biocultural diversity for global sustainability. For example, it is known that indigenous peoples and traditional communities manage 95% of the world's genetic resources (Maffi & Woodley, Reference Maffi and Woodley2012) and act as stewards of approximately 40% of protected areas and ecologically intact systems worldwide (Garnett et al., Reference Garnett, Burgess, Fa, Fernández-Llamazares, Molnár, Robinson and Leiper2018). The associated knowledge and local management practices thus become crucial given that the health, agriculture and economy of people around the world are partially or totally dependent on these resources and environments (Corona-M, Reference Corona-M2018).

2. Expanding the biocultural paradigm and its applications

While the concept of biocultural diversity has been commonly applied to indigenous and traditional communities, especially in the context of a ‘crisis narrative’ (Brosius & Hitchner, Reference Brosius and Hitchner2010), recent developments have significantly expanded its meanings to include other social and ecological contexts. Cocks (Reference Cocks2006) and Cocks and Wiersum (Reference Cocks and Wiersum2014) argue that the concept of biocultural diversity is equally applicable to social groups who do not adopt traditional lifestyles and do not live in largely pristine natural environments. Research amongst rural and urban communities in the Global South heavily impacted by hegemonic socio-economic processes shows that more modernized communities maintain cultural practices reliant on natural environments and high biodiversity (Cocks, Reference Cocks2006; Emperaire & Eloy, Reference Emperaire and Eloy2008) and that people retain cultural and spiritual values associated with natural landscapes and vegetation in rural and urban contexts (Cocks, Vetter, & Wiersum, Reference Cocks, Vetter and Wiersum2018; Cocks & Dold, Reference Cocks and Dold2012; Cocks et al., 2015, unpublished data). Along the same lines, Buizer, Elands, and Vierikko (Reference Buizer, Elands and Vierikko2016) have proposed that biocultural diversity should be considered as a reflexive and sensitizing concept that can be used to assess the different values and knowledge of different human groups living with biodiversity within different contexts. For these authors, biocultural diversity emphasizes the importance of urban green areas for the quality of life in growing cities. In this way, cultural interactions with nature form a crucial part of the city's cultural heritage and identity (Elands, Wiersum, Buijs, & Vierikko, Reference Elands, Wiersum, Buijs and Vierikko2015).

In the field of sustainability science, the biocultural paradigm overlaps strongly with the social-ecological systems framework. In particular, in early work on social-ecological systems (Berkes, Colding, & Folke, Reference Berkes, Colding and Folke2003; Berkes, Folke, & Colding, Reference Berkes, Folke and Colding2000), there is strong emphasis on the co-evolution and deep intertwinedness of humans and nature, which is mirrored in the concept of biocultural diversity (Gavin et al., Reference Gavin, McCarter, Mead, Berkes, Stepp, Peterson and Tang2015; Loh & Harmon, Reference Loh and Harmon2005; Maffi, Reference Maffi2005). Moreover, in resilience thinking, biocultural diversity is regarded as a crucial component of social-ecological systems and a key resource for surviving crises, adapting to change, and crafting new social-ecological systems in the future. As part of these discussions, it has been suggested that the concept of ‘ecosystem services’ can be usefully expanded to ‘nature's contributions to people’ (Díaz et al., Reference Díaz, Pascual, Stenseke, Martín-López, Watson, Molnár and Shirayama2018), highlighting the cultural context of co-construction of nature's benefits and emphasizing the role of biocultural diversity. Currently, the social-ecological systems approach and terminology is also used in a much broader sense, and the term ‘bioculture’ is employed to emphasize tightly intertwined and co-evolving social-ecological systems, cultural dimensions and implications in such systems (e.g. Barthel, Crumley, & Svedin, Reference Barthel, Crumley and Svedin2013; Haider, Reference Haider2017; Hirons et al., Reference Hirons, Boyd, McDermott, Asare, Morel, Mason and Norris2018; Kealiikanakaoleohaililani et al., Reference Kealiikanakaoleohaililani, Kurashima, Francisco, Giardina, Louis, McMillen and Yogi2018).

The biocultural paradigm has also been adopted by intergovernmental organizations, programs and platforms (e.g. UNESCO, the Convention for Biological Diversity [CBD] and the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services [IPBES]). The concept of biocultural diversity was taken on by a joint UNESCO-CBD programme in 2010, the International Year of Biodiversity, to promote reciprocal knowledge exchange of cultural, ethnic, linguistic and religious diversity, and to foster dialogue for sustainable development based on recognition of and respect for different knowledge systems, including the knowledge of indigenous peoples and local communities (United Nations, 2010). Biocultural perspectives were then integrated into the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011–2020 that included 20 Aichi Biodiversity Targets, within which biocultural heritage was seen as a key promoter of resilience (United Nations, 2010). A plan of action on customary sustainable use of biological diversity was established to ensure the participation of indigenous and local communities in such a Strategic Plan (United Nations, 2010). The IPBES platform, created in 2012 to strengthen knowledge foundations for better policy through science, recognized from the onset the role of biocultural diversity in shaping nature, as reflected in its conceptual framework (Díaz et al., Reference Díaz, Demissew, Carabias, Joly, Lonsdale, Ash and Zlatanova2015). In this context, a Task Force was also created to foster the recognition of the knowledge that indigenous people and local communities possess, the way it is constructed and evolves over time, and its relevance for the governance of biodiversity from local to global levels.

In the Global South, particularly in Latin America, the biocultural paradigm has become instrumental for indigenous rights movements and the political agenda of environmental civil society organizations (Argumedo, Reference Argumedo2011; Martínez-Esponda et al., Reference Martínez-Esponda, Benítez, Ramos Pedrueza, García Maning, Bracamontes and Vázquez2017; Panduro, Reference Panduro2014). A unifying feature of this perspective is the claim that indigenous conservation knowledge, practices and territories (including food production, biocultural heritage and memory) are threatened by globalized capitalism and neo-colonial powers (Declaration of Ixtlán, 2017). Social movements find in the biocultural paradigm an essential political tool to demand land rights protection, focusing on diverse forms of life in concrete (often contested) territories. Related concepts in this context include biocultural heritage (‘patrimonio biocultural’ with its connotations of birthright and ownership) (Argumedo, Reference Argumedo, Amend, Brown, Kothari, Phillips and Stolton2008; Boege, Reference Boege2008, Reference Boege2015), biocultural memory (Toledo & Barrera-Bassols, Reference Toledo and Barrera-Bassols2008) and sociobiodiversity (Almeida, Reference Almeida2012).

A growing array of discourses and applications enlivens an evolving biocultural paradigm, which informs the study, practice and politics of the vital interconnections between culture and nature. However, the local contributions of this paradigm may be more easily deducible than its role in promoting global sustainability, as it is discussed below.

3. The biocultural paradigm's crucial role in global sustainability

The biocultural paradigm is inherently systemic and place-based, focusing on practices, knowledge, values and governance systems that relate specific human groups with their environment. As Sterling et al. (Reference Sterling, Filardi, Toomey, Sigouin, Betley, Gazit and Bergamini2017: p. 1800) note, “all biocultural approaches are social-ecological in nature, but not all social-ecological approaches frame interactions from locally relevant cultural perspectives”. Despite being associated with human-nature connections from local cultural viewpoints, we argue that the biocultural paradigm is decisive to global sustainability for at least four reasons.

3.1. Global sustainability strongly relies on diversity

Whilst biodiversity has been proven to be crucial for ecosystem functioning (Cardinale et al., Reference Cardinale, Duffy, Gonzalez, Hooper, Perrings, Venail and Naeem2012), cultural diversity constitutes an invaluable source of knowledge, ways of knowing and learning, governance mechanisms, management practices and innovations toward sustainability that provides options for the future of humanity and the Earth (Barthel et al., Reference Barthel, Crumley and Svedin2013; Maffi, Reference Maffi1998; Singh, Pretty, & Pilgrim, Reference Singh, Pretty and Pilgrim2010; Sterling et al., Reference Sterling, Filardi, Toomey, Sigouin, Betley, Gazit and Bergamini2017; Tengö et al., Reference Tengö, Hill, Malmer, Raymond, Spierenburg, Danielsen and Folke2017). Biocultural diversity refers to the interdependence between biological and cultural diversity, indicating how significant ensembles of biological diversity are managed, conserved and even created (e.g. agrodiversity) by different cultural groups, many of which have had low environmental impact, thus offering significant stewardship examples of strong relevance for other groups across the globe (Berkes et al., Reference Berkes, Folke and Colding2000; Brondizio & Tourneau, Reference Brondizio and Tourneau2016; Garnett et al., Reference Garnett, Burgess, Fa, Fernández-Llamazares, Molnár, Robinson and Leiper2018; Gavin et al., Reference Gavin, McCarter, Mead, Berkes, Stepp, Peterson and Tang2015). In a highly interconnected world, where local activities can affect and be affected by social-ecological dynamics occurring in other parts of the planet, such culture-based sustainable practices are of benefit to all humans, and facilitate alternative ways of being.

3.2. The biocultural paradigm emphasizes the connections between nature and human well-being, shifting the attention in sustainability debates from economic development to cultural values that guide non-instrumental relationships with nature

Relational values that focus on identity, well-being and a sense of stewardship/responsibility are found across a great variety of cultural groups and societal contexts (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Balvanera, Benessaiah, Chapman, Díaz, Gómez-Baggethun and Turner2016). Relational values have become iconic through cultural manifestations such as Ubuntu in South Africa, Sumak Kawsay in Latin America, Hālau ‘Ōhi‘a in Hawaii, the Gandhian Economy of Permanence in India, Pope Francis’ encyclical letter Laudato Si’ and the Degrowth movement in Europe. These and other value systems that emphasize individual and collective well-being, and the fundamental dependence of well-being on the environment, tend to conserve and construct forms of relationship with nature and the human community that may potentially counter the negative impacts of the progressive commodification of nature and the loss of traditional governance systems (Acosta, Reference Acosta2016; Fuentes-George, Reference Fuentes-George2013; Gómez-Baggethun & Ruiz-Pérez, Reference Gómez-Baggethun and Ruiz-Pérez2011; Gudynas, Reference Gudynas2015; Kothari, Demaria, & Acosta, Reference Kothari, Demaria and Acosta2014; McCauley, Reference McCauley2006).

3.3. The biocultural paradigm is a useful approach to address the social justice aspects of sustainability

Cultural groups contribute differently to environmental changes that currently challenge all humans. Although in the term ‘Anthropocene’ (Crutzen, Reference Crutzen2002) our species as a whole is identified as the major driver of global change, it is important to clarify that the alterations in the climate, water cycles, biodiversity and in various ecosystem dynamics are mainly caused by the forms and levels of production and consumption in industrial and post-industrial societies rather than all of humanity (Baskin, Reference Baskin2015; Malm & Hornborg, Reference Malm and Hornborg2014; Moore, Reference Moore2016, Reference Moore2017). The Great Acceleration (Steffen, Crutzen, & McNeill, Reference Steffen, Crutzen and McNeill2007) and its significant impacts both on economic wealth and the ecological crisis have been largely associated with the demands and activities of a small fraction of the human population. Steffen and collaborators (Reference Steffen, Broadgate, Deutsch, Gaffney and Ludwig2015) show, for example, that in 2010 the OECD countries accounted for 74% of global GDP while representing only 18% of the global population. Wiedman and collaborators (Reference Wiedmann, Schandl, Lenzen, Moran, Suh, West and Kanemoto2015) found that with every 10% increase in GDP the material footprint of nations increases by 6%, and that as wealth grows countries not only consume more materials from nature but also tend to rely more on those abroad through international trade. Biocultural perspectives highlight these disparities, as well as the economic, political and epistemic inequalities that lie at the basis of intercultural exchanges and environmental conflicts (Boege, Reference Boege2015; Leff, Reference Leff2017). Key areas of biocultural diversity are often under intense dispute, with a great number of local communities facing challenges such as land dispossession and large-scale development projects (Apgar, Ataria, & Allen, Reference Apgar, Ataria and Allen2011). Biocultural approaches can cast light on the contrasting values, knowledge systems and practices that underpin social-ecological conflicts and contribute, through collaborative and engaged research (Gavin et al., Reference Gavin, McCarter, Berkes, Mead, Sterling, Tang and Turner2018; Salomon et al., Reference Salomon, Lertzman, Brown, Wilson, Secord and McKechnie2018; Temper, Del Bene, & Martinez-Alier, Reference Temper, Del Bene and Martinez-Alier2015), to the construction of peace and justice, necessary conditions for any attempt toward local and global sustainability.

3.4. Global sustainability depends on the enactment of culturally pertinent policies that can be articulated across governance levels and actors

The lack of biocultural approaches in the formulation of top-down policies by governments operating at all scales may lead to the implementation of culturally inappropriate actions, which can result in unproductive and even harmful processes, generating the loss of control over place, resources, knowledge and practices (Sterling et al., Reference Sterling, Filardi, Toomey, Sigouin, Betley, Gazit and Bergamini2017). The effectiveness of environmental governance depends on the direct involvement of local and indigenous populations in political platforms that reconcile different cultural perspectives (Brondizio & Tourneau, Reference Brondizio and Tourneau2016) and the right to self-determination via traditional governance systems (Lovera, Reference Lovera2010).

The adoption of the biocultural paradigm by academia, practitioners and policy makers may catalyse the joint construction of relevant knowledge, sustainable practices and policies by different social actors. This would imply a greater contribution to sustainability, from local to global scales. Fruitful collaboration between sectors relies, however, on the understanding of different biocultural conceptions, knowledge and applications put forward by distinct actors and their agendas. In the following section, we discuss some of the key features of four main biocultural discourses in the field of sustainability as well as some significant connections between them. These discourses emphasize distinct aspects of the biocultural paradigm's contributions to local and global sustainability, depending on their locus of production and objectives.

4. Biocultural discourses in academia, practice and policy

Discourses are both a product and a producer of power as they constitute a response to perceived needs in specific historical and political contexts, and have the potential to drive change by framing problems and solutions (Foucault, Reference Foucault1975). Understanding how different discourses shape human-nature interactions and promote change across actors at different scales is thus key for sustainability (Clement, Reference Clement2013; Hajer, Reference Hajer1995). Our purpose here is not to provide a thorough analysis of how biocultural discourses are constituted or have contributed to sustainability, but to briefly characterize them and discuss some of their connections in order to better understand the limits and potentialities of the biocultural paradigm.

Drawing on the authors’ involvement with distinct discursive fields, and on different sources of information (scientific and grey literature, websites, international policy documents, declarations, conferences), we identified four major biocultural discourses in the field of sustainability. Two of these discourses are represented by scholars working in the fields of (i) social-ecological systems and sustainability science and (ii) anthropology and ethnobiology. Another discourse has emerged among civil society organizations, social movements and engaged scholars ([iii] indigenous rights movements and political ecology) and the fourth in international policy arenas ([iv] intergovernmental bodies) (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of biocultural discourses in academia, practice and policy.

All of these approaches recognize the reciprocal links between cultural and biological diversity; however, some emphasize epistemic dimensions from a more ecological (i) or anthropological (ii) perspective, while others focus on ethico-political aspects from a bottom-up (iii) or top-down approach (iv). The strength of the connections between the discourses and their influence on each other vary, as shown in Figure 1 and further described below.

Fig. 1. Connections between biocultural discourses. Arrows indicate the degree of mutual influence between discourses. Some discourses influence each other more strongly (solid black arrows), whereas some have weaker connections (solid grey arrows). Some other connections reflect an unbalanced influence between discourses (arrows with color gradients; black arrowheads point to the discourse that is influenced to a larger degree, and grey arrowheads point to the discourse that is influenced to a lesser degree). A more detailed characterization of these connections is provided in the text.

The social-ecological systems and sustainability science discourse is scientific and often employs quantitative methodologies. Even though inclusive and transdisciplinary approaches are gradually increasing, social-ecological perspectives generally tend to place less emphasis on the role of power relations and social inequalities. Due to their scientific status and orientation towards policy influence, this type of narrative strongly informs international bodies (such as IPBES) and maintains synergic ties with other scholarly discourses, but is not significantly influenced by indigenous rights movements. The ties with anthropology and ethnobiology have a long history, where the social-ecological systems literature has drawn from these bodies of work, for example, on indigenous and local knowledge and institutions (e.g. Berkes et al., Reference Berkes, Colding and Folke2003; Gavin et al., Reference Gavin, McCarter, Mead, Berkes, Stepp, Peterson and Tang2015); on cultural aspects of ecosystem services (e.g. Comberti, Thornton, Wyllie de Echeverria, & Patterson, Reference Comberti, Thornton, Wyllie de Echeverria and Patterson2015; Pröpper & Haupts, Reference Pröpper and Haupts2014) and values, including relational values (e.g. Chan et al., Reference Chan, Balvanera, Benessaiah, Chapman, Díaz, Gómez-Baggethun and Turner2016; West et al., Reference West, Haider, Masterson, Enqvist, Svedin and Tengö2018).

Anthropological and ethnobiological discourses often draw on ethnographic and other forms of qualitative research. While biocultural diversity in this context was originally applied to the study of indigenous peoples in remote and more pristine areas, this perspective has extended the notion of bioculturality to modernized communities, and agricultural and urban contexts. The political emancipatory dimension of biocultural views is not a main focus of these discourses, although they argue strongly for indigenous knowledge and practices to be given prominence in development and policy. Anthropological and ethnobiological discourses have had some influence on indigenous movements and some impact on international policy. Stronger synergies are identified with social-ecological scientific discourses with which there is a shared academic basis and on-going cross-fertilization, with many scholars publishing in anthropology, ethnobiology and social-ecological realms (Buizer et al., Reference Buizer, Elands and Vierikko2016; Gavin et al., Reference Gavin, McCarter, Mead, Berkes, Stepp, Peterson and Tang2015; Vogt et al., Reference Vogt, Pinedo-Vasquez, Brondízio, Rabelo, Fernandes, Almeida and Dou2016).

Indigenous movements and political ecologists have produced biocultural discourses that focus primarily on ethico-political dimensions with a bottom-up approach. These discourses are strategically used to advocate for environmental and indigenous rights and are informed by ecological and anthropological biocultural knowledge, although the term ‘biocultural’ is not always explicitly employed. The focus on power relations and social inequities is largely expressed through the overt opposition to capitalist globalization and neo-colonialism, with an overall discredit of global intergovernmental initiatives because of their limited impact on national and local levels. The political nature of these discourses often implies a simplification of social-ecological knowledge and the essentialization of ethnic groups, that is, the idealization of the indigenous.

The biocultural discourses produced within and in relation to intergovernmental organizations, programs and platforms (e.g. UNESCO, CBD and IPBES) are also chiefly ethico-political, strongly informed by science, and have a top-down orientation. Strong links are maintained between these international bodies and social-ecological discourses (Díaz et al., Reference Díaz, Demissew, Carabias, Joly, Lonsdale, Ash and Zlatanova2015, Reference Díaz, Pascual, Stenseke, Martín-López, Watson, Molnár and Shirayama2018). Other academic discourses are also incorporated in international policy, but with lesser impact. While progress has been made to integrate indigenous knowledge, further steps are needed to truly bridge across knowledge systems (Tengö et al., Reference Tengö, Hill, Malmer, Raymond, Spierenburg, Danielsen and Folke2017). In some aspects of its work, the CBD has created platforms for engagement with representatives from indigenous peoples and local communities that have led to their biocultural perspectives gaining greater prominence and power. Despite such efforts, there is little adoption or effective application of the recommendations generated in these international arenas by national states and local authorities, whose decisions are heavily informed by competing economic narratives.

In sum, there is limited interaction between scientific, conservation-focused approaches of both international policy makers and academics (themselves in a position of power and privilege within the capitalist system) on one hand, and the overt political focus of indigenous rights movements who struggle for social justice and autonomy over land and the use of biocultural resources. As a matter of fact, abstract scientific approaches and decontextualized policy recommendations stand in stark contrast to civil society and social movements’ discourses, which derive from marginalized groups’ lived experiences of land dispossession and vulnerability in the face of the dominant economic, political and cultural models. In spite of these differences in form and focus, the biocultural discourses summarized above oppose the homogenizing effects of globalization and many of them assert the need for changes in how development and sustainability are both conceived and driven by official institutions and corporations. Some discursive synergies also include the claim for a broader participation of cultural groups in knowledge co-production and political decisions at all scales.

5. Ways forward toward a paradigm shift

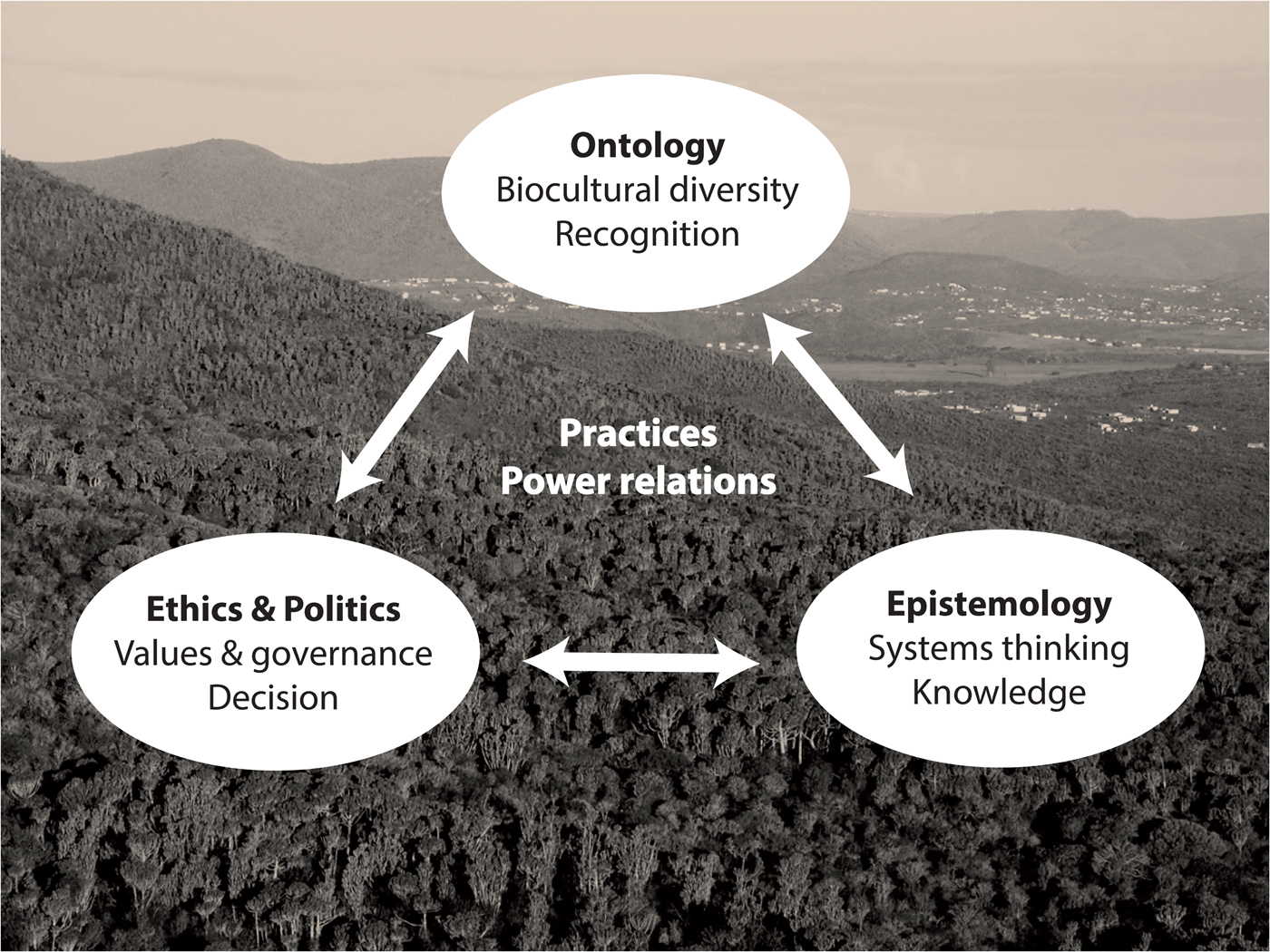

The current plurality of biocultural discourses reflects the diversity of socio-cultural positions, communities of practice and political orientations involved in their construction and application. Some tensions between these stances are inevitable and can provide meaningful challenges for further dialogue and political changes. Without advocating complete integration or the disappearance of significant discursive differences, we propose here that biocultural approaches recognize and articulate the ontological dimension of biocultural diversity, an epistemological dimension through systems thinking, and an ethico-political dimension taking explicitly into account plural values, governance systems and power relations (Figure 2). These dimensions are essential to connect forms of understanding across actors and to strengthen actions toward global sustainability, as we show below.

Fig. 2. Ontological, epistemological and ethico-political dimensions of the biocultural paradigm are interconnected and manifested through cultural practices and power relations embedded in specific biocultural landscapes (Photo: Tony Dold).

The ontological dimension of the biocultural paradigm refers to the recognition of diverse ways of conceiving and experiencing nature and their cultural embeddedness. Acknowledging the diversity of ontological systems co-existing on the planet is a necessary condition for a full understanding of human-nature relationships. Many of these relationships, which are not completely conditioned by hegemonic culture, are particularly important given their historical invisibility but crucial contribution to local and global well-being and sustainability (Masterson et al. unpublished data). Making biocultural diversity visible in academia, practice and policy has implications on decisions and actions at different scales. The study of biocultural manifestations in urban contexts and the extension of the concept to non-indigenous groups enlarge the diversity spectrum and contribute to novel knowledge and applications. In any case, a broader attention to Global South experiences is key to reveal how a great number of (currently threatened) human-nature relations contribute to global sustainability.

Holistic or systems thinking broadly characterizes the biocultural paradigm's epistemology. This type of approach focuses on the interaction between socio-cultural and ecological components, acknowledging their interdependence and dynamic nature, as proposed by the social-ecological systems perspective (Berkes et al., Reference Berkes, Folke and Colding2000). Systemic forms of understanding involve the direct participation of indigenous and local knowledge holders through transdisciplinary processes, boundary work, action research and other forms of place-based collaborative knowledge production. Such engagement needs to be carried out in ways founded in respect, equity and usefulness for all involved (Tengö, Brondizio, Elmqvist, Malmer, & Spierenburg, Reference Tengö, Brondizio, Elmqvist, Malmer and Spierenburg2014; Tengö et al., Reference Tengö, Hill, Malmer, Raymond, Spierenburg, Danielsen and Folke2017). Collaboratively produced knowledge with a systemic perspective creates more holistic and complexity-oriented ways of understanding sustainability (Ayala-Orozco et al., Reference Ayala-Orozco, Rosell, Merçon, Bueno, Alatorre-Frenk, Langle-Flores and Lobato2018; Merçon, Ayala-Orozco, & Rosell, Reference Merçon, Ayala-Orozco and Rosell2018; Mistry & Berardi, Reference Mistry and Berardi2016) and may impact on the values, decisions and practices that constitute biocultural realities. This could lead to greater recognition and protection of biocultural systems as well as influence policies and sustainable practices beyond the local. To enable this potential and allow for real collaboration in contexts of power asymmetries, the study of and engagement with diverse biocultural knowledge systems should take a series of ethico-political and epistemological considerations into account, including, for example, the use of co-formulated biocultural protocols, dedicated implementation of Free Prior and Informed Consent, and support of indigenous-led initiatives and movements (Bavikatte & Robinson, Reference Bavikatte and Robinson2011; Ward, Reference Ward2011). Such change in perspective would demand a strong commitment and capacity building for a constructive engagement in high-level policy fora.

The ethico-political dimension encompasses values and governance regimes whose decisions impact on the ontological manifestation and understanding of biocultural systems and vice-versa. For example, the biocultural paradigm can cast light on how relational values and local governance systems contribute to nature conservation, thus providing elements for the legitimation at national and international levels of such systems in indigenous peoples’ struggles for self-determination (Brondizio & Tourneau, Reference Brondizio and Tourneau2016; Garnett et al., Reference Garnett, Burgess, Fa, Fernández-Llamazares, Molnár, Robinson and Leiper2018; Rozzi, Reference Rozzi, Rozzi, Pickett, Palmer, Armesto and Callicott2013). Moreover, the development and implementation of full participatory mechanisms to include the values, governance systems, needs and knowledge of vulnerable groups in policy making may ensure more comprehensive understandings of biocultural systems and hence more culturally appropriate actions (Ruiz-Mallén, Corbera, Novkovic, Calvo-Boyero, & Reyes-García, Reference Ruiz-Mallén, Corbera, Novkovic, Calvo-Boyero and Reyes-García2013; Sterling et al., Reference Sterling, Filardi, Toomey, Sigouin, Betley, Gazit and Bergamini2017).

Despite being present in the practices that sustain all dimensions (ontology, epistemology, ethics and politics), power relations have had little recognition in biocultural discourses (Table 1). As various scholars have demonstrated, neglecting the role of structural, actor-based and discursive power leads to partial and naive understandings of human-nature interactions (Boonstra, Reference Boonstra2016; Bryant, Reference Bryant1998; Meadowcroft, Reference Meadowcroft2009; Smith & Stirling, Reference Smith and Stirling2010; Zimmerer & Bassett, Reference Zimmerer and Bassett2003). Understanding biocultural systems from a power relations perspective is needed to account for different types of inequities that accentuate cultural groups’ vulnerability in the face of hegemonic cultural, political and economic forces. With such understanding, the biocultural paradigm can be used to counter globalization's homogenizing drivers and the loss of cultural practices, languages, knowledge, values and governance systems. This emancipatory nature of the biocultural paradigm places social and environmental justice at the core of global sustainability.

6. Conclusions

In a growingly globalized world, where the accelerated loss of biological and cultural components leads to profound inequitative social and ecological repercussions, biocultural approaches collectively represent a promising paradigm. By focusing on the connections between cultural and biological diversity, human well-being, social justice and the formulation of culturally pertinent policies, biocultural discourses hold great transformative potential. The full actualization of such potential relies, however, on the construction of bridges between current discourses, embodied by scientists, practitioners and policy makers who tend to emphasize distinct dimensions of the biocultural paradigm (ontological, epistemological or ethico-political). In this sense, the recognition and articulation, in theory, practice and policy, of biocultural diversity, holistic or systems thinking, plural values, governance systems and power relations contribute to a more encompassing and effective perspective. From local landscapes, urban spaces and social movements to academia and international policy, discursive bridging and inter-sectorial collaboration potentialize the crucial contributions of the biocultural paradigm to local and global sustainability.

Author ORCIDs

Juliana Merçon, 0000-0001-7249-1994

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the initial contribution of Karla Karina Pérez López for her support in the systematic literature review. JM, PB, JAR and BA-O are also thankful for the support of the Socioecosystems and Sustainability Network (Red de Socioecosistemas y Sustentabilidad, CONACyT, Mexico). MT acknowledges support from the Swedish Research Council. The initial discussions presented here were held at the Second Open Science Conference of the Programme for Ecosystem Change and Society (PECS) of Future Earth, in Oaxaca, Mexico. Inspiration for this paper also came from the Multi-Actor Dialogues on Biocultural Diversity and Social-Ecological Resilience, held in Ixtlán, Oaxaca, and financially supported by Sida (through SwedBio) and PECS.

Author contributions

All authors participated, at some stage, in the conception and design of the article, as well as data gathering. JM, SV, MT, MC and PB wrote the article and all authors reviewed it.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

None.