Organizational research on sustainability has examined the causes of pro-environmental action and its consequences for the organizations undertaking it. Intuitively, pro-environmental action is often perceived as antithetical to performance, especially short-term financial performance. And yet, some organizations successfully employ win–win environmental strategies, with positive bottom lines for both the natural environment and organizational stakeholders such as employees and investors (Margolis & Walsh, Reference Margolis and Walsh2003). In this paper, we consider the performance implications of pro-environmental action by universities, and specifically divestment from fossil fuel.

Universities are key players in global efforts to mitigate climate disruption. Researchers uncover and communicate the facts of rapid global warming, and in so doing provide a foundation for policy making, behavioral change, and organizational efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Climate science also informs teaching at universities, across disciplines, equipping future leaders with an understanding of the causes and consequences of anthropogenic threats to climate stability. Beyond their core missions of research and teaching, universities also participate organizationally in efforts to combat climate change, for example by reducing their own carbon footprints. Another front in higher education efforts is the movement to divest from fossil fuel.

Divestment by prominent institutions increases political pressure on governments to pass ‘restrictive legislation affecting stigmatised firms’ (Ansar et al., Reference Ansar, Caldecott and Tilbury2013), and has hindered firms' ability to pay for new fossil fuel projects (Cojoianu et al., Reference Cojoianu, Ascui, Clark, Hoepner and Wójcik2021). These positive environmental impacts led more than 11,000 scientists from 153 countries to describe the movement for divestment from fossil fuel as one of a few ‘encouraging signs’ amid all the ‘profoundly troubling’ statistics concerning the global climate (Ripple et al., Reference Ripple, Wolf, Newsome, Barnard and Moomaw2019). Universities are a prime target of this movement (Stephens et al., Reference Stephens, Frumhoff and Yona2018). By the end of 2020, 190 institutions of higher education in 13 countries had committed to divest their endowments of stock in fossil fuel. Most are divesting fully, whereas others are divesting partially, by selling off holdings in a sub-category of fossil fuel, such as coal, and/or oil mined from tar sands (Supplementary Table S1 and Figure S1). In some cases, universities that initially committed only to partial divestment later strengthened their commitments to cover all coal, oil, and gas.

1. The best divest: divestors best their competition

Although researchers often employ financial metrics to assess the overall performance of business firms, we use world rankings as a proxy for the overall performance of universities. Such rankings aim to track the quality and quantity of research and teaching, and also reputational status (see Supplementary materials; Vernon et al., Reference Vernon, Balas and Momani2018). Although rankings have limitations, as do other performance indicators (Espeland & Sauder, Reference Espeland and Sauder2007), they increasingly command the attention of the people who run universities (Muller, Reference Muller2018). Moreover, their inclusion of larger numbers of universities over time has at least reduced the risk of omitting certain important universities altogether.

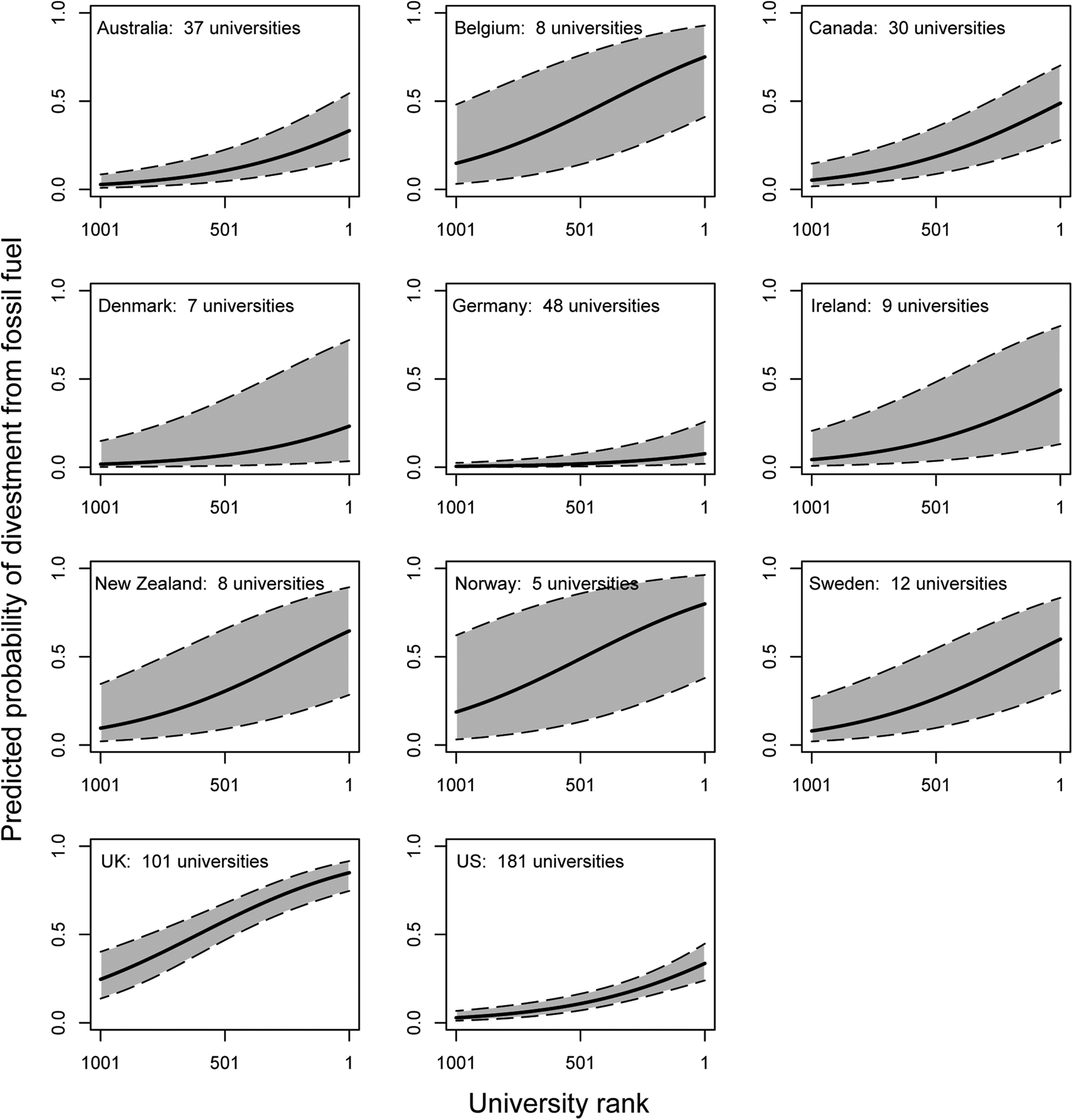

Cursory inspection of the most comprehensive world rankings, cross-referenced to the list of universities divesting from fossil fuel, reveals that five of the top 10, 19 of the top 50, and 33 of the top 100 had committed to divestment by the end of 2020 (Supplementary Table S2 and Figure S2). Across all 1527 universities in the 2021 rankings, those that made that commitment average 382 ranks higher than those that have not. This global pattern holds within most countries as well, and a statistical model affirms both country and rank as significant predictors of divestment (Figure 1). For a sub-sample of universities in the USA and Canada, we also considered other potential correlates of divestment, specifically the number of students, size of endowment, type of endowment, and regional politics. Of these, only the last relates significantly to divestment. In more conservative states and provinces, universities are less likely to divest. But even after controlling for that effect, higher-ranking universities are more likely to divest. On average, each incremental position higher in the rankings goes along with 0.3% greater odds of divesting from fossil fuel (the odds of something being its probability divided by one minus that probability). For details of the results reported above and below, as well as similar results from treating partial and full divestment as separate categories, see the Supplementary materials.

Figure 1. Predicted probabilities of divestment from fossil fuel. Derived from a binomial logistic regression of divestment on country and 2021 ranking. Results shown with 95% confidence intervals for each of the 11 countries with at least one ranked, divesting university. Larger sample sizes yield more precise estimates of country effects, hence narrower confidence intervals. The x axes run from lower-ranked universities on the left to higher-ranked universities on the right, with smaller numbers representing higher ranks.

These findings indicate that, just as economic profitability correlates with certain forms of ecological responsibility among companies, academic reputation correlates with a specific form of ecological responsibility among universities. However, they do not clarify the reasons for this correlation. In the business world, the mechanisms run in both directions. On the one hand, companies that perform better often have the slack and resources to allocate attention and effort to environmental issues (Etzion, Reference Etzion2007). On the other hand, social responsibility can lead to greater engagement, creativity, and knowledge sharing in ways that improve employee productivity (Glavas, Reference Glavas2016) and increase pride and commitment, thereby boosting employee performance (Rupp & Mallory, Reference Rupp and Mallory2015). There is also evidence that pro-environmental activities both attract (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Willness and Madey2014) and retain (Bode et al., Reference Bode, Singh and Rogan2015) better employees. Finally, having a pro-environmental reputation may allow businesses to hire equally competent workers at lower salaries (Burbano, Reference Burbano2016).

We, therefore, used time lags to test specifically for effects of university rankings on divestment and vice versa. Both tests yield positive results. The rankings for 2013, the year before the first ranked universities divested from fossil fuel, correlate significantly with subsequent divestments. This suggests an effect of rank on divestment.

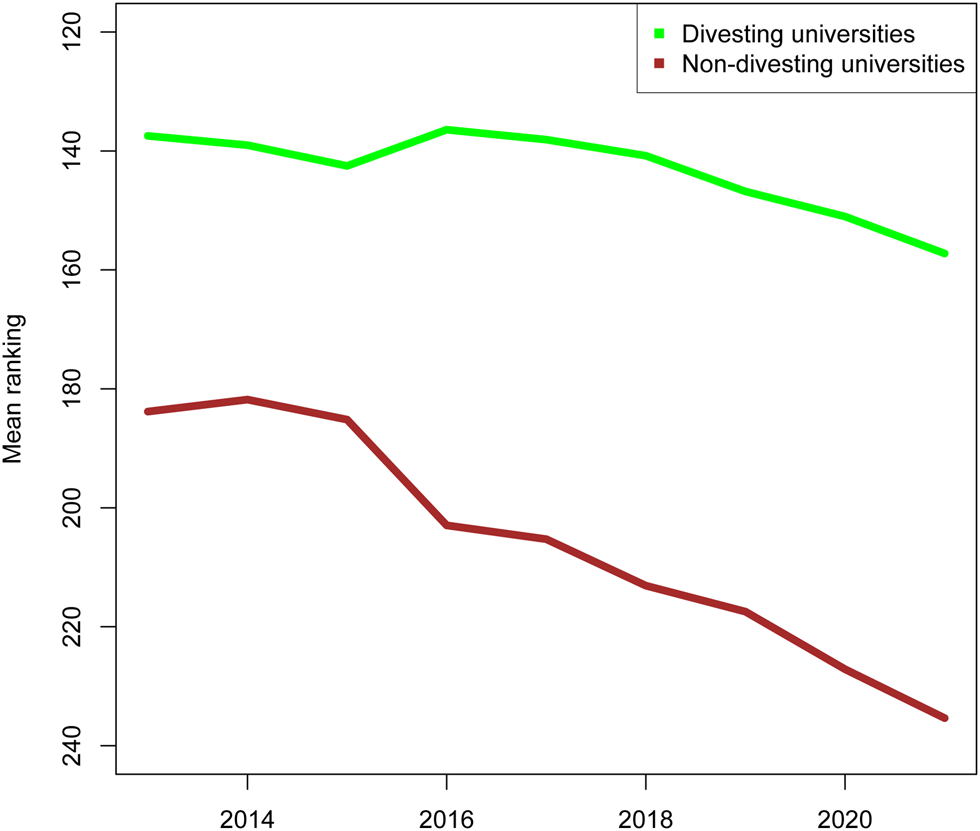

We also find evidence of an effect in the opposite direction. The gap between the average rankings of divesting vs. non-divesting universities has widened over time (Figure 2). A more fine-grained analysis indicates the year of divestment as a turning point at which divesting universities tend to begin out-performing non-divesting but otherwise similar universities. Before divesting, universities have no significant tendency to improve or decline in the rankings relative to their closest non-divesting competitors. But after divesting, universities do rise in the ranks relative to those same competitors, by an average of 2.1% per year. These results suggest a positive effect of divestment on subsequent rankings.

Figure 2. Average rankings of divesting vs. non-divesting universities over time. To keep the sample constant from year to year, this graph shows results for only the universities ranked in all years from 2013 through 2021. As the total number of universities ranked has increased, the average rankings of both divestors and non-divestors in this 347-university sample have declined. But non-divesting universities' rankings have declined more. This widened the gap between the two, from 46 ranks in 2013 – the year before any of these universities had divested – to 78 ranks in 2021, by which time 84 of them had divested.

For an illustrative although somewhat extreme example, consider a pair of universities in the USA that both ranked fairly highly in the first years of our sample period: the University of Maryland, College Park and the University of Florida. From 2013 to 2016, Maryland declined in the world rankings by 20.6%, from 97th to 117th place. Meanwhile, Florida improved by 1.6%, from 122nd to 120th place. These changes put Florida closer in rank than any other US university was to Maryland in 2016. Later that year, the University System of Maryland Foundation committed to sell off all fossil fuel stock from their billion-dollar endowment fund. Since that announcement, Maryland has improved in rank, and ended up at 90th place in 2021. In contrast, Florida has still not committed to either partial or full divestment, and declined to 152nd place in the 2021 rankings. Most comparisons between matched pairs of divesting vs. non-divesting universities are not as dramatic as this one. Moreover, there are many exceptions to the general pattern the Maryland–Florida pair exemplifies. However, the overall trend is for other post-divestment universities to also out-perform non-divesting universities located in the same countries and having similar rankings in the year of divestment.

2. Implications for the divestment movement

In the nearly 7 years that have elapsed since the first divestment by a ranked university, their pace has remained relatively slow and even. This trajectory is consistent with research on the diffusion of contested practices among other kinds of organizations, that is, practices which have moral and ethical entanglements (Briscoe & Safford, Reference Briscoe and Safford2008). Over time, additional actors increasingly follow suit, thereby reinforcing a positive feedback dynamic (Abrahamson & Fairchild, Reference Abrahamson and Fairchild1999). If this pattern holds, growth in the number of highly ranked universities that divest will make the norm of divesting increasingly coercive (Etzion, Reference Etzion2014) and is likely to lead lower ranked universities to eventually divest.

This progression will potentially have implications for universities as well as for society more broadly. At the level of the university, divestment seems to offer a reasonable risk/reward ratio. Financial research has determined that divestment has negligible impacts on investment returns (Trinks et al., Reference Trinks, Scholtens, Mulder and Dam2018), but improved performance is a possibility. Universities that act as climate leaders by divesting from fossil fuel are likely better positioned to prepare students for the grand challenges ahead. This may help explain the tendency for universities to move up the ranks after divesting. These modest reputational gains complement the scientific, moral, and political reasons for divesting from fossil fuel.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/sus.2021.19

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge input on this research from Michael Adamson, Juan Giraldo, Mark Goldberg, Shaun Lovejoy, Antonina Scheer, Sydney Sybydlo, Jacqueline Tam, and Margaret Winchell.

Author contributions

GMM, DE, and AC conceived and designed the study. GMM and DE gathered the data. GMM performed the statistical analysis. DE, GMM, and MA wrote the article.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (Grant Number 892-2017-3026 to DE).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare none.

Research transparency and reproducibility

Most data are publicly available from sources identified in the text. Contact GMM for the R code used to carry out the analyses, and/or news sources used to refine the divestment data.