1. Introduction

Continued dependence on natural resource extraction is a key sustainability concern. Development models that rely on the expansion of extractive frontiers lead to overexploitation (Moore, Reference Moore2015; Svampa, Reference Svampa2019). This model is characterised by the simultaneous production of value, wealth and systemic damage to ecosystems and human health (Weinberg, Reference Weinberg2021). One such example is the increasing environmental damage due to the development of large-scale extractive projects, which primarily affect local communities.

The social impacts of environmental damage are unevenly distributed (Holifield et al., Reference Holifield, Chakraborty and Walker2017; Martinez Allier et al., Reference Martinez Allier, Temper, Del Bene and Scheidel2016). In particular, local communities living near mining projects are particularly affected by environmental degradation, reflecting a global problem of environmental injustice (Urkidi & Walter, Reference Urkidi, Walter, Holifield, Chakraborty and Walker2017). This has engendered protests and social movements calling for transformation of the development model towards sustainability and environmental justice.

Against this backdrop, multilateral agencies, extractive companies and states have developed institutional frameworks to protect fragile ecosystems from extraction and to mitigate environmental damage, including no-go zones for extractive activities and environmental impact assessments to mitigate the impacts of large-scale extractive projects (Goodland, Reference Goodland2012). However, these policies have not prevented environmental degradation in extractive areas, demonstrating the limitations of the mitigation approach and the need for effective transformative initiatives.

An important initiative that illustrates the tension between mitigation and transformative approaches at the local level is the adoption of environmental monitoring procedures to assess the quality of specific environmental conditions, such as water or air, at specific sites over a given period of time. States and companies have introduced such procedures in many extractive territories with a view to improving environmental mitigation policies (Dourojeanni et al., Reference Dourojeanni, Rada and Ramirez2012). However, several studies have questioned their effectiveness, arguing that this institutional, top-down scientific approach limits the involvement of local communities and disregards local knowledge (Himley, Reference Himley2014; Yacoub et al., Reference Yacoub, Boelens and Voz2016). As a result, environmental monitoring initiatives have little legitimacy with local communities who see them more as mechanisms to facilitate the expansion of extractive industries than as institutional innovations to promote sustainability (Ulloa et al., Reference Ulloa, Godfrid, Damonte, Quiroga and López2021).

Local communities and civil society groups have therefore begun implementing their own community-based environmental monitoring (CBEM) (Fernandez-Gimenez et al., Reference Fernandez-Gimenez, Ballard and Sturtevant2008). This is an outcome of interactive multi-actor governance schemes involving community members as well as foundations, NGOs or scientific experts throughout the various stages of the monitoring process: design of objectives, protocols, sampling, and interpretation or dissemination of results (Fernández-Giménez et al., Reference Fernandez-Gimenez, Ballard and Sturtevant2008). These local initiatives undoubtedly represent a progressive institutional innovation whereby local actors can take ownership and legitimise environmental monitoring (Godfrid et al., Reference Godfrid, Damonte and Lopéz Minchán2021), furthering a mitigation approach that links monitoring to the extractive project.

To what extent, then, can CBEM be seen as transformative institutional innovations that favour sustainability? In this paper, we argue that community-based monitoring is a transformative initiative that allows local and civil society actors to acquire knowledge and experiences and, in turn, challenge the prevailing model of natural resource governance based on expert knowledge and top-down institutional schemes. The knowledge and practices acquired by local actors allows them to push governments and companies for more democratic decision-making on management of natural resource extraction, going beyond mitigation approaches to a focus on managing socio-environmental impacts. CBEM entails alternative institutional arrangements structured from below that promotes local community involvement and synergistic interactions between stakeholders in proposing institutional innovations for sustainability in extractive territories. In addition, CBEM fosters community recognition of environmental injustices by raising awareness of unevenly distributed environmental impacts.

To develop our argument, we analyse two experiences of CBEM: one related to air quality in the Quintero Punchucavi Bay, Valparaiso Province, Chile, and another on water quality in the Cañipia Basin, Espinar Province, Peru. In these areas, local communities have opted to develop their own environmental monitoring processes to challenge prevailing arrangements led by the state or mining companies. These communities have chosen to focus on monitoring air and water quality, respectively, because these are perceived as the most pressing issues and because they still only have limited capacity to undertake multiple integrated environmental monitoring. We explore the ways in which local actors, responding to their specific socio-political contexts and using their own resources, develop collaborative strategies to implement CBEM initiatives aimed at highlighting persistent environmental impacts and their effects on local livelihoods, thus contesting state and corporate narratives of extractive development. As a contribution to the literature, we show how transformative narratives can be translated into specific actions and grounded in specific territories. Local communities' strategies for promoting transformations are diverse as they are culturally embedded and reflect their own experiences, resources and contexts.

This paper is divided into five sections. After this introduction we present our methodology and conceptual framework based on the concept of transformation towards sustainability. We then present our two case studies to analyse the emergence of a new transformative institution for environmental monitoring. Finally, we offer some concluding remarks.

2. Methodology

In methodological terms, we analyse each case to compare the similarities and differences (Stake, Reference Stake1995). Case selection was based on purposive sampling, whose ‘logic and power […] lies in selecting in formation-rich cases for study in depth. Information-rich cases are those from which one can learn a great deal about issues of vital importance to the purpose of the research […]’ (Patton, Reference Patton1990, p. 169). To collect the data, between 2021 and 2023 we conducted semi-structured interviews and ethnographies in situ (in Valparaíso, Chile and Espinar, Peru), including 18 interviews and 4 ethnographic records in Chile and 25 interviews and 3 ethnographies in Peru in 2022 and 2023. Additional information on the interviews and ethnographies can be found in Annexes 1 and 2. The number of interviews corresponds to the data saturation criteria: ‘[…] the collection of qualitative data to the point where a sense of closure is attained because new data yield redundant information’ (Moser & Korstjensc, Reference Moser and Korstjensc2018, p. 11). The interviews were carried out and analysed by the authors following the qualitative content analysis method (Mayring, Reference Mayring2000), which is based on a series of steps and procedures for reading and interpreting texts within their context of communication. The interviewees were members of the social organisations tasked with monitoring as well as participants involved in the community monitoring experience given our interest in reconstructing the perspective of the social actors who identify themselves as the communities affected by environmental contamination. We also interviewed state environmental monitoring and oversight officials, as well as representatives of the mining sector, to study the relationships and perceptions between actors. To ensure anonymity the interviewees are referred to only by their initials, excluding surnames. In addition, we systematised information from secondary sources, including reports by public agencies, specialist literature, legislation and publications by social organisations.

3. Transformations towards sustainability

Fundamental to the literature on ‘transformations’ or ‘transformations towards sustainability’ is the understanding that modern societies base their life model on a mode of interaction with nature that has devastating and unsustainable effects on ecosystems and life in general. This leads to the idea that reversing this situation requires significant and fundamental transformations rather than minor and inconsequential changes (Kapoor, Reference Kapoor2007).

Transformations require structural and transversal changes to the different social systems (economic, political, cultural, societal) to create new patterns of society–nature interaction that allow for fairer, more equitable and sustainable ways of life for humanity without affecting the stability and resilience of the Earth system (Feola, Reference Feola2015; O'Brien, Reference O'Brien2012; Patterson et al., Reference Patterson, Schulzb, Vervoortc, Van der Held, Widerberga, Adlere, Hurlbertf, Andertong, Sethih and Barauj2017). We study how CBEM challenges the dominant mitigation approach to environmental damage and proposes a shift from mitigating impacts to addressing and preventing the causes of environmental degradation.

Moreover, transitions towards sustainability are goal oriented (Geels, Reference Geels2011). This implies a social recognition of a situation as undesirable and necessitates a level of social organisation to alter the situation. The way in which these transformations towards sustainability are configured, their frameworks of interpretation and the narratives around them are socially constructed therefore implies a process of social definition of what constitutes the problem, for whom it is a problem and how to solve it. Drawing from studies on climate change, O'Brien (Reference O'Brien2012) posits some key questions: What kinds of transformations are considered necessary and why? Who decides whether or not they are necessary? Thus, thinking about transformations should include not only ‘technical’ solutions but also power, knowledge, norms, agency and scales. As an institutional initiative CBEM can therefore be regarded as ‘deliberative transformations’: the product of participation, debate and questioning of the beliefs, values and conditions that created the existing structures, systems and behaviours (O'Brien, Reference O'Brien2012).

Hence, in our study, transformative initiatives are closely related to environmental justice issues since awareness and responses to uneven environmental damage are key issues in explaining CBEM. The political ecology and environmental justice literature shows how local rural and indigenous communities are disproportionately vulnerable to environmental damage and its consequences (Peluso & Watts, Reference Peluso and Watts2001; Pellow, Reference Pellow2007; Johnston, Reference Johnston and Crumley2001; Bullard Reference Bullard2005; McGregor, Reference McGregor, Atapattu, Gonzalez and Seck2021). This is fundamental to understanding how local communities’ awareness of their vulnerability to pollution has driven the emergence of CBEM.

Transformations towards sustainability are complex, dynamic, political and multi-level (social, institutional, economic, technological, ecological) (Patterson et al., Reference Patterson, Schulzb, Vervoortc, Van der Held, Widerberga, Adlere, Hurlbertf, Andertong, Sethih and Barauj2017). Different social actors, social movements or networks of actors may be involved in the construction of transformative initiatives, as in other instances of social change (Kooiman & Bavinck, Reference Kooiman, Bavinck, Bavinck, Chuenpagdee, Jentoft and Kooiman2013; Melucci, Reference Melucci1999; Zald et al., Reference Zald, Morril, Rao, Zald, Morril and Rao2005). As Scoones et al. (Reference Scoones, Stirling, Abrol, Atela, Charli-Joseph, Eakin, Ely, Olsson, Pereira, Priya, van Zwanenberg and Yang2020) asserts, the agency of local communities is fundamental to implementing transformative processes. In our cases, local communities affected by extractive activities coalesce with other actors to promote new transformative forms of environmental monitoring.

Transformation likewise entails institutional interaction with multiple actors as well as processes of political tension or conflict insofar as the different actors within a society are differentially affected by the changes: some may gain or lose benefits depending on the results of the alterations (Meadowcroft, Reference Meadowcroft2011). Thus, the idea of transformation alludes to processes that can induce changes in various orders that regulate life: in perception or social meanings, forms of power distribution, social coordination schemes, institutional arrangements or organisational structures (Olsson et al., Reference Olsson, Gunderson, Carpenter, Ryan, Lebel, Folke and Holling2006). In extractive territories, the empowerment of local communities in environmental decision-making often leads to conflict and the articulation of different power constellations (Lave, Reference Lave2012). In our study, the different dynamics of conflict and cooperation between different actors are key to understanding the emergence of CBEM, lending specificities to the transformative process in each case study.

4. Case studies

In Chile and Peru mining has long been a key economic activity. In 2016 the two countries together produced 40% of the world's refined mine copper (Lagos, Reference Lagos2017). According to USGS (2021), both countries possess sufficient mineral reserves to continue expanding their copper extraction for many decades. However, this growth could be hampered by the evolution of socio-political and environmental factors in relation to new mining projects (Lagos, Reference Lagos2017).

Several studies in Chile and Peru have analysed the socio-environmental impacts of mining extraction and refining. The negative effects include the impact on glaciers (Brenning, Reference Brenning, Orlove, Wiegandt and Luckman2008), high emissions of polluting gases (Gayo et al., Reference Gayo, Muñoz, Maldonado, Lavergne, Francois, Rodríguez, Klock-Barria, Sheppart, Alonso-Hernandez, Mena-Carrasco and Urquiza2022), soil contamination (González et al., Reference González, Neaman, Rubio and Cortés2014; Montenegro et al., Reference Montenegro, Fredes, Mejias, Bonomelli and Olivares2009), water pollution and effects on human health (Berasaluce et al., Reference Berasaluce, Mondaca, Schuhmacher, Bravo, Sauvé, Navarro-Villarroel, Dovletyarova and Neaman2019; Gayo et al., Reference Gayo, Muñoz, Maldonado, Lavergne, Francois, Rodríguez, Klock-Barria, Sheppart, Alonso-Hernandez, Mena-Carrasco and Urquiza2022). In turn, various studies have explored effects on society, such as the multiplication of conflicts around water (Bauer, Reference Bauer2015; Calderón et al., Reference Calderón, Benavides, Carmona, Gálvez, Malebrán, Rodríguez, Sinclaire and Urzúa2016; Prieto, Reference Prieto2017), socio-environmental conflicts (Carranza et al., Reference Carranza, Varas-Belemmi, De Veer, Iglesias-Müller, Coral-Santacruz, Méndez, Torres-Lagos, Squeo and Gaymer2020; Delamaza et al., Reference Delamaza, Maillet and Neira-Martinez2017) or impacts on ethnic identities (Bolados, Reference Bolados2016; Carrasco, Reference Carrasco Moraga2014). Drawing on these frameworks we present our case studies.

4.1 Chile

4.1.1 The context of CBEM's emergence

In Chile, we analysed an experience of community environmental monitoring in the Quintero-Puchuncaví Bay (Valparaíso Region) on the central coast. Together, the municipalities of Quintero and Puchuncaví have a population of approximately 50,500 people (Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas, 2017). Since the 1960s, with the construction of a copper smelter and the Ventanas refinery, the Quintero-Puchuncaví Bay has become one of the biggest industrial complexes but also one of the most polluted areas in Chile (Berasaluce et al., Reference Berasaluce, Mondaca, Schuhmacher, Bravo, Sauvé, Navarro-Villarroel, Dovletyarova and Neaman2019).

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s industrial activities in the bay have expanded. At present the industrial complex hosts around 16 companies, including a copper smelter, thermoelectric plants, petrochemical and oil refiners, chemical processing companies and gas terminals, among others. Despite this industrial growth, the bay is one of the poorest areas in the country (Bolados, Reference Bolados2016). Most inhabitants work in the industrial complex, as artisanal fishers, or as peasant smallholders, but fishing and agriculture have been affected and diminished by environmental pollution problems (Sabatini et al., Reference Sabatini, Mena and Vergara1996). Residents are therefore exposed to a dual vulnerability: poverty and contamination. The biggest problem has been the high emissions of diverse air pollutants such as particulate matter, nitrogen oxides, sulphur dioxide and heavy metals (Gayo et al., Reference Gayo, Muñoz, Maldonado, Lavergne, Francois, Rodríguez, Klock-Barria, Sheppart, Alonso-Hernandez, Mena-Carrasco and Urquiza2022). Communities in the bay have experienced negative health effects: cardiovascular and respiratory mortality risks as well as increased cases of cancer (Berasaluce et al., Reference Berasaluce, Mondaca, Schuhmacher, Bravo, Sauvé, Navarro-Villarroel, Dovletyarova and Neaman2019; Salmani-Ghabeshi et al., Reference Salmani-Ghabeshi, Palomo-Marín, Bernalte, Rueda-Holgado, Miró-Rodríguez, Cereceda-Balic, Fadic, Vidal, Funes and Pinilla-Fil2016).

5. Social conflicts and institutional response: state and corporative monitoring

Towards the end of Pinochet's dictatorship (1973–1989) protests against pollution began to emerge along with environmental defence groups, such as Puchuncaví Environmental Defense Committee (Sabatini et al., Reference Sabatini, Mena and Vergara1996). Throughout the long history of environmental pollution in the bay, contamination episodes have prompted mass mobilisations, the emergence of female-led environmental organisations (Bolados, Reference Bolados2016) and different cycles of protest (Espinoza Almonacid, Reference Espinoza Almonacid2022). Residents, grouped into different social organisations, complain that they have been impoverished by the effects of environmental contamination and that their communities have been transformed into a ‘sacrifice zone’ (Bolados, Reference Bolados2016): a concept that has been used extensively by the environmental justice literature in reference to areas and communities exposed to high levels of pollution and environmental degradation that have been sacrificed in the name of national development or economic growth (Scott & Smith, Reference Scott and Smith2017). Interestingly, around 2015 the idea of ‘sacrifice zone’ became popular among grassroots movements in Chile. A women's social organisation, ‘Mujeres de Zona de Sacrificio en Resistencia’ (Women of the Sacrifice Zone in Resistance), was formed to highlight the environmental injustice experienced by women and other dwellers of the bay and attribute it to the unjust economic model that impoverishes, sickens and imposed environmental degradation (Bolados, Reference Bolados2016).

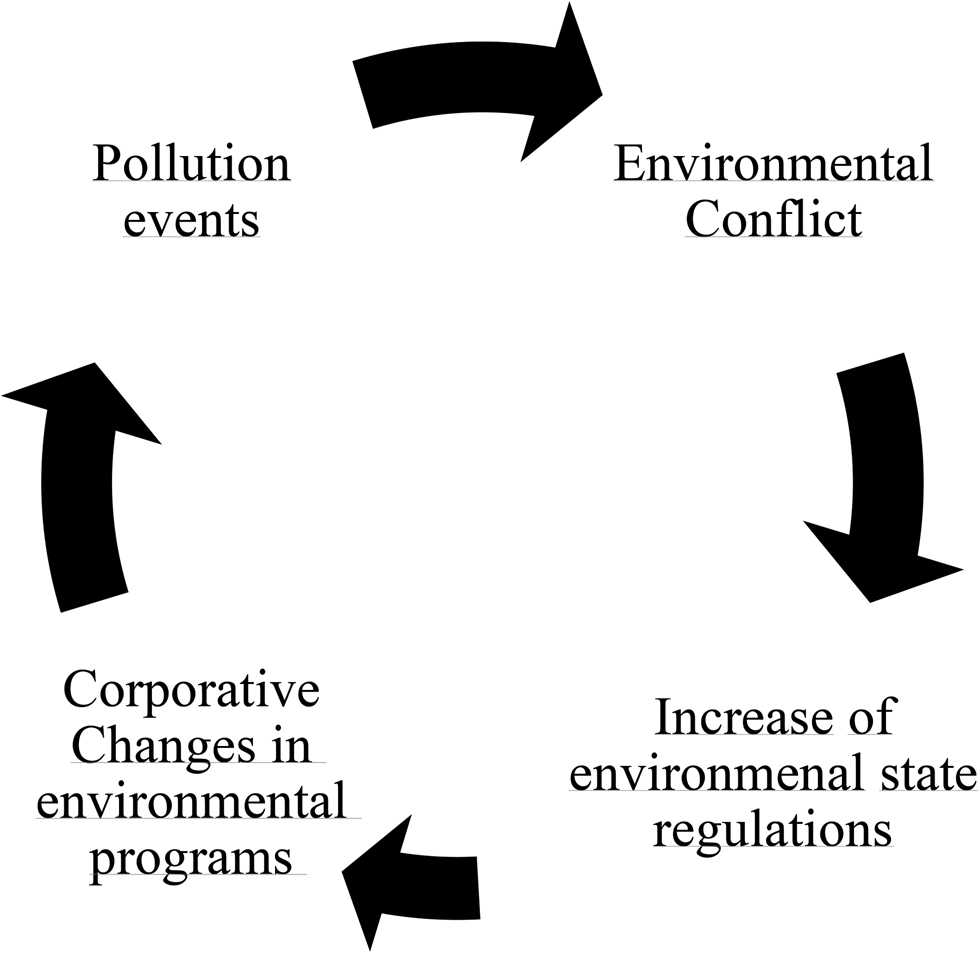

The chronology of contamination events is lengthy and has been widely analysed by other studies (Bolados, Reference Bolados2016; Sabatini et al., Reference Sabatini, Mena and Vergara1996). Multiple actors (state, companies and social organisations) have been involved in transforming air quality governance in Chile over the last 30 years: an experience marked by disputes, confrontations and occasional synergies. The dynamics of change involve a spiralling sequence of environmental accidents, social conflicts, changes in environmental regulations by the state and shifting business practices (a graphic representation of these dynamics is shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1. Dynamics of changes in air governance.

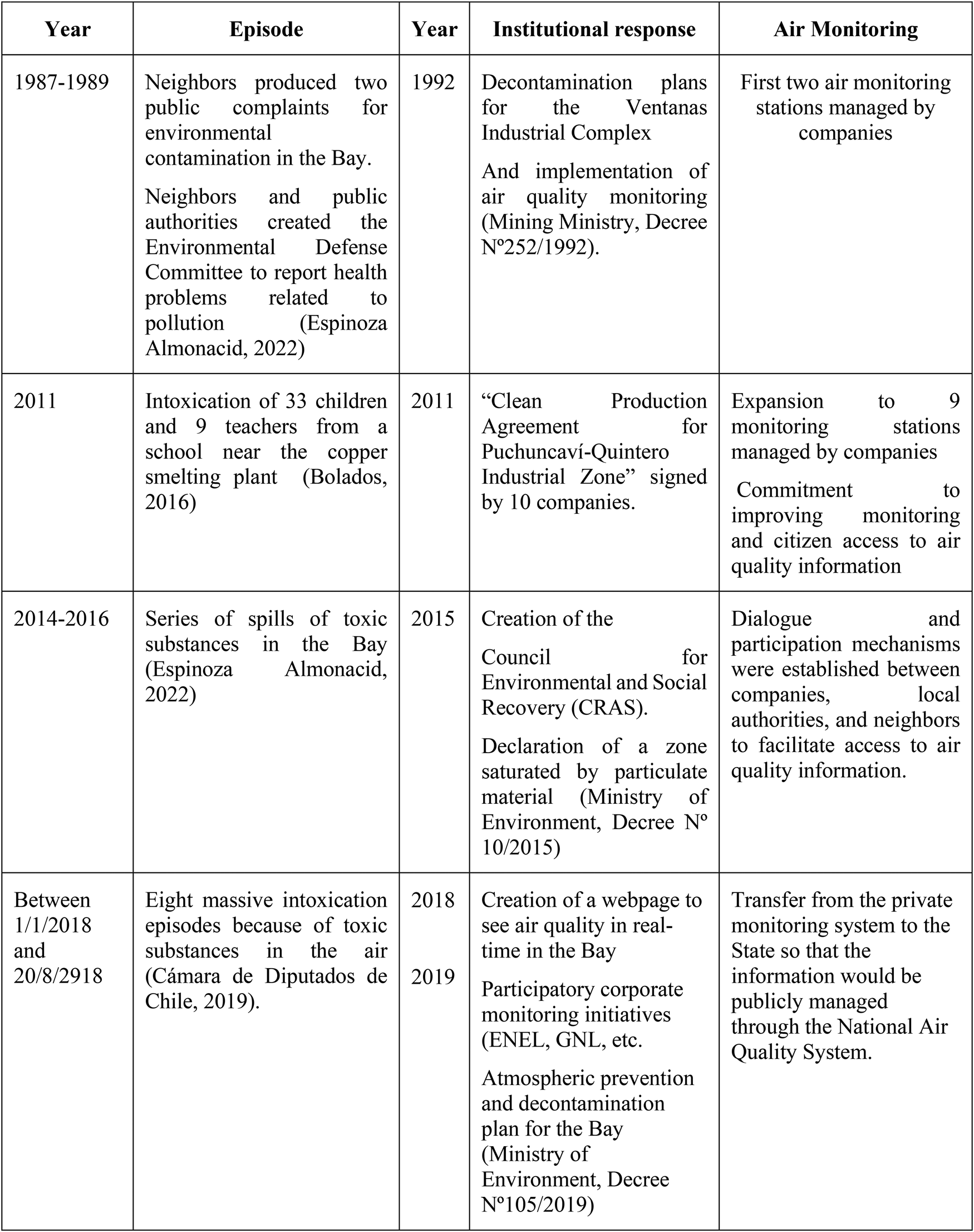

To understand changes in air governance and institutional responses, four key moments can be discerned, as outlined in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Institutionalisation of state and corporative monitoring.

Pollution episodes and subsequent conflict prompted at least five types of state and corporate responses in terms of monitoring: (1) the creation of a network of air quality monitoring stations, in 1992; (2) business strategies to make information on emissions transparent; (3) mechanisms for dialogue and citizen participation to learn about air quality; (4) corporate monitoring with citizen participation; and (5) an early warning system on air quality conditions.

Despite the institutional changes to promote greater environmental regulation and new mechanisms for citizen participation, the local population distrusts official monitoring and is concerned about possible recurrence of pollution (Espinoza Almonacid, Reference Espinoza Almonacid2022; Rogers Cerda, Reference Roger Cerda2020). In this context, experiences of air-quality monitoring have emerged in the Quintero-Puchuncaví Bay communities.

5.1 Community air monitoring in Quintero-Puchuncaví

In 2017, a CBEM experience began to emerge in Quintero-Puchuncaví Bay (V.M.A., personal communication, 26 April 2022) following the accumulation of conflicts between residents who endure pollution, companies operating in the bay and the state, which has done little to address environmental injustices over the years. Quintero-Puchuncaví inhabitants have rehearsed multiple resistance actions to express their grievances about pollution but also to build social alternatives. These actions have included micro resistances (Tironi, Reference Tironi2018), protest and street performance (Bolados, Reference Bolados2016) and legal actions (Espinoza Almonacid, Reference Espinoza Almonacid2022).

In 2017, after many years of participation in disparate social and environmental groups, social leaders decided to come together as an informal community organisation and develop a community environmental program (Quintero Mide, 2022; C.L, personal communication, 8 July 2022). The experience encompassed different processes: environmental education on air quality and Chilean regulation; participation in public mechanisms such as the Council for Environmental and Social Recovery to discuss decontamination plans and social alternatives for the bay; fundraising to build air quality sensors and develop a web platform for data display; device testing; and decision-making regarding what or how to measure (J.R. personal communication, 4 November 2022; C.L., personal communication, 20 October 2022).

Unlike the plans of companies and the state, which have generally been oriented to mitigating pollution problems, locals involved in monitoring focus on challenging the current development model and criticising ecological damage distribution. For example, one mitigation measure implemented by the state was to close schools during peaks of pollution – such as in 2011 – in order to prevent new intoxication events. The locals opposed this measure, demanding that the schools be reopened and that the plants instead bear the brunt by reducing production and emissions. These calls were partially translated into a new decontamination plan enacted in 2019 (Ministry of Environment, Decree N°105/2019).

Communities not only seek ways to monitor pollution conditions but actively question which companies pollute the most, trying to determine the most affected areas of the bay and at what times the effects of pollution are felt the most. One of their long-term goals through the monitoring experience is to map pollutants in the bay with the aim of identifying and denouncing the companies that pollute the most and building citizen protection mechanisms such as avoiding certain areas with higher levels of pollutants. One of the advantages of the CBEMs is the environmental training provided so that participants (residents and local leaders) can read and understand specific technical information about air quality (e.g. about particulate matter and the risks it generates). During emergencies, some members of the social organisation leading the CBEM read, interpret, simplify and share the technical information with their neighbours through social media, WhatsApp groups and radio programs. This circulation of information serves as an informal early warning system to keep people off the streets or reduce their risk exposure.

Through the different processes involved in monitoring, residents question central elements of environmental governance: Who manages the measurement instruments? What is measured? How is the data processed? Who manages the measurement information in the system? Why does the information delivery system stop working during pollution peaks? (C.L., personal communication, 8 July 2022; V.M.A., personal communication, 26 April 2022). Questioning official monitoring is a way of critiquing the natural resource governance in Chile and raising public awareness of environmental injustice. More profoundly, the organisation involved in monitoring, as well as other inhabitants, question environmental governance but also the development model based primarily on the extraction of natural resources. In the interviews, organisation members complained that the community bears the brunt of pollution and asserted that they no longer wish to be a sacrifice zone (N.N., personal communication, 11 July 2022; C.L., personal communication, 11 July 2022).

5.2 Institutional innovations towards sustainability

In 2019, following a legal claim filed by the Ombudsman for Children and other NGOs, Chile's Supreme Court ruled that the pollution peaks of 2018 had violated fundamental rights established in the Constitution. For this reason, the court established that an Emergency Plan for Quintero-Puchuncaví communes should be formulated (Supreme Court of Chile, Ruling No. 5888-2019). This plan was ultimately drafted in 2019, and an attempt to modify the network of monitors followed in 2021 (Ministry of the Environment, Resolution No. 80, 2021). These modifications were highly contested by residents and social leaders; in the words of the director of Chile Youth network and the Quintero-Puchuncaví Movement for Children, ‘we no longer trust measurements’ (Mennickent, Reference Mennickent7/4/2021).

Faced with social rejection, in 2022 the Minister of Environment called a public consultation on the new monitoring network. Justifying this decision, the environmental authority in the Valparaíso region stressed ‘We seek to generate trust in the community’ (Ministry of the Environment, 13/7/2022). As evidenced in the statements, the lack of public confidence in environmental monitoring remains a key problem. When the consultation finally took place between July and October 2022, more than 300 citizen submissions were made (Ministry of the Environment, 6/4/2023). The design of the new network was presented by the environmental authorities on 4/6/2023. The proposed new network has 14 monitoring stations for Quintero-Puchuncaví and Concón (the neighbouring municipality) and expand the types of chemical, volatile compounds and particulate matter measured (Ministry of the Environment, 6/4/2023).

The citizens in Quintero-Puchuncaví, through organisations such as that promoting monitoring, have pressured Chilean institutions into modifying air governance. Community monitoring helped citizens to acquire new knowledge, develop new framing and raise public awareness about environmental injustice. Social questioning and the emergence of community monitoring have promoted institutional innovation of air governance in Chile. The convergences and divergences between the framings of social organisations, companies and the state have been fraught with tensions and disagreements. For Fressolli et al. (Reference Fressoli, Arond, Abrol, Smith, Ely and Dias2014), innovation dynamics can also arise through the tension and negotiation that arise from dissimilar perspectives coming into contact. The lack of public confidence in state and corporate monitoring has been a driving force behind community monitoring. These efforts and their different stages, including environmental training, could be essential to promoting ‘transformations towards sustainability’ because the current production model and its unevenly distributed ecological costs are called into question.

5.3 Peru

5.3.1 The context of CBEM's emergence

In Peru, our CBEM experience is situated in the province of Espinar, Cusco department, in the southwest Andes. Espinar province comprises eight districts and has a total population of 57,582 inhabitants, of which 34,861 live in the district of Yauri, the provincial capital. The province is also home to 78 peasant communities.

Large-scale copper mining in the province commenced with the Tintaya project in 1982, initially operated by Empresa Minera Estatal Asociada Tintaya SA (EMATINSA) in the Salado River basin. In the 1990s, amid liberal reforms, the mine came under the ownership of the Australian company Broken Hill Proprietary (BHP). In 2012, the second phase of the project was inaugurated at Antapaccay in the Cañipía river basin. Since 2013, the company has been owned by the multinational Glencore. The project encompasses three tailings deposits (Ccamacamayo, Huinipampa and the former Tintaya pit), dumps, a concentrator and an industrial oxide plant.

Nevertheless, mining development manifests a profile of poverty and environmental injustice. According to the INEI poverty map (2018), Espinar's poverty rate ranges from 23.9% to 38%. The population engages in activities such as commerce, mining-related services, agriculture and livestock, with some residents employed directly at the mine. In this context, it is crucial to stress that the rural population living in the proximity of the operation has borne the most significant impacts, experiencing water, soil and air pollution as well as livelihood loss (Oxfam Community Aid Abroad, 2003; Pinto Herrera, Reference Pinto Herrera2014).

As regards the impact on human health, exposure to heavy metals such as cadmium, arsenic, mercury and lead is linked to kidney disease, weak joints and bones, lung damage and other health issues (Amnistía Internacional, 2021). This precipitates tensions between the state, the mine and social organisations in determining the causality of contamination. In this context, state governance has been characterised by hesitant and ambiguous studies, a mitigation-centred approach, and sluggish responses, perpetuating environmental injustice (Gamu & Dauvergne, Reference Gamu and Dauvergne2018; Paredes, Reference Paredes2022).

6. Social conflicts and institutional response: state and corporative monitoring

Ever since mining began in Espinar, there have been local demands for the operator to participate in local development. The first major demonstration took place on 21 May 1990, which yielded the first direct benefits such as electrification and road paving in the province. In the major social mobilisations that followed (2003, 2005m and 2012), environmental demands related to water contamination from mine tailings and the depletion of springs were central (Preciado & Alvarez, Reference Preciado and Álvarez2016).

In this regard, environmental monitoring and participatory control was included in the two dialogue mechanisms that emerged as a result of the social mobilisations: the Framework Agreement of 2003 and a 2004 Roundtable between the company and the affected communities. The former resulted in benefits such as a 3% profit reinvestment as well as the creation of a joint and participatory municipal environmental committee. The latter provided for the implementation of environmental monitoring plans involving local communities.

In this context, a number of participatory environmental and health monitoring studies have been carried out by various stakeholders. As part of the 2004 Roundtable, three air, water and soil monitoring processes took place (2002, 2005, 2010), while the Supervisory Agency for Energy and Mining Investment conducted eight monitoring campaigns on surface and groundwater effluents between 2008 and 2010, and the National Health Institute (CENSOPAS) conducted two studies on human health and heavy metals in 2010 and 2012–2013. The results showed that some of the permissible limits were exceeded (CooperAcción, 2016).

The Environmental Assessment and Control Agency (OEFA) and the National Water Authority (ANA), the state institutions responsible for overseeing the environment and monitoring water quality, respectively, also carried out their own monitoring. The official results showed that mining activity in Espinar complied with environmental standards and maximum allowable limits, which, in the view of the local population, did not reflect the contamination they had experienced first-hand (V.M., personal communication, 13 August 2022; A.S., personal communication, 18 August 2022). This sparked mistrust among residents, who accused the state institutions of acting in cahoots with the mining company (V.M., personal communication, 13 August 2022; N.C., personal communication, 15 August 2022; A.S., personal communication, 18 August 2022). Demands arose for new environmental studies and monitoring, culminating in the mobilisations and roundtables of 2011 and 2012.

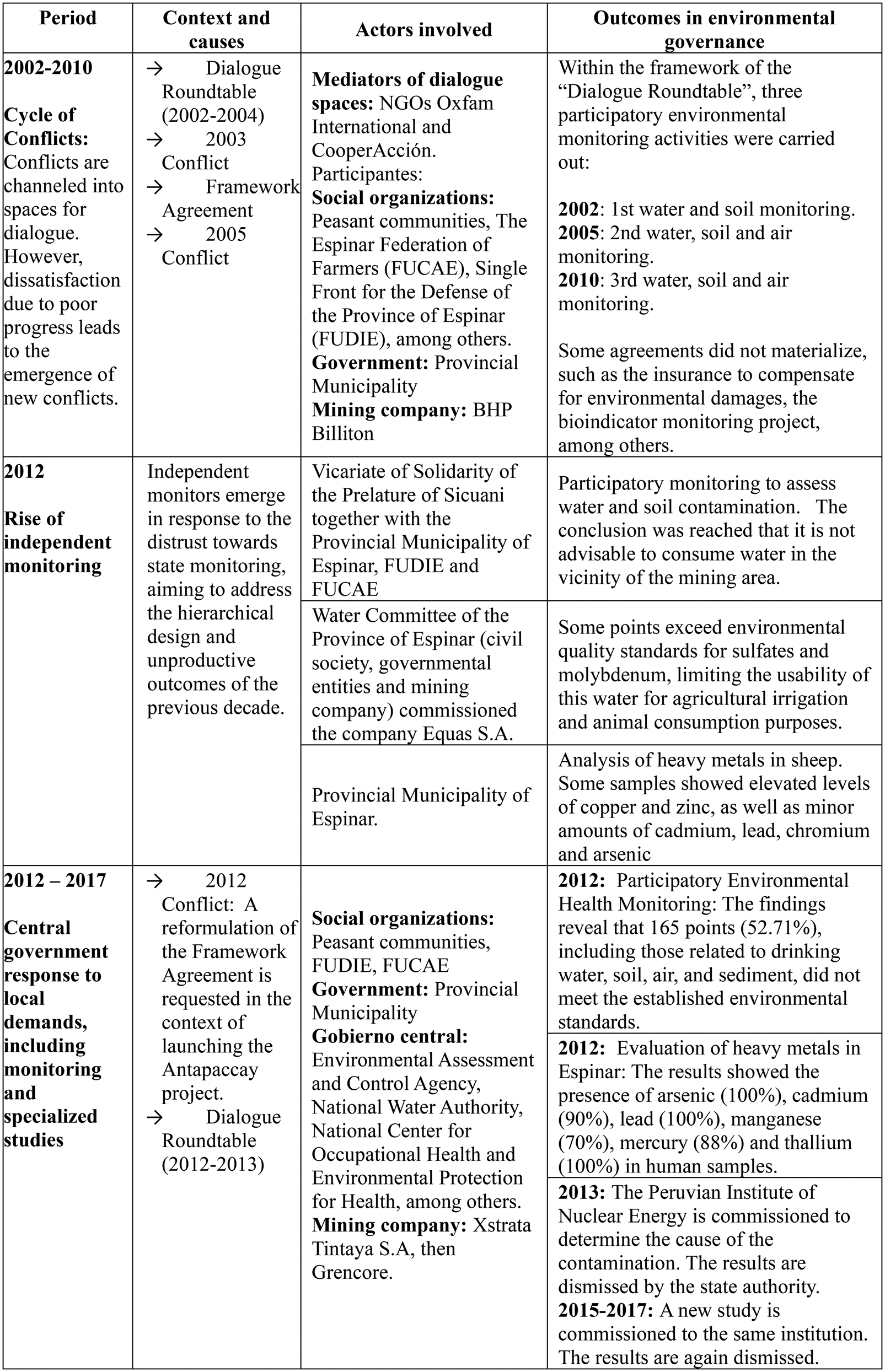

Sizeable social mobilisation events acted as catalysts for participatory monitoring initiatives in Espinar, as well as for specialised studies such as testing for heavy metals in human samples and the analysis of contamination causality. Figure 3 outlines the actors involved in the main conflicts and the institutional response. In this context, connections at the local and global levels, as well as transnational support, are crucial for exerting pressure and eliciting responses from the state and companies, as highlighted by Paredes (Reference Paredes2022). Therefore, we contend that these confrontations served to develop synergy and, in turn, temporary agreements related to monitoring and specialised studies.

Figure 3. Community-based water monitoring in the Cañipía–Espinar basin.

In the context of conflicts and demands for independent monitoring, several initiatives have been led by the Catholic Church and private companies. Between 2011 and 2012, the Vicariate of Solidarity of the Prelature of Sicuani conducted monitoring to assess water and soil contamination. In 2012, the Water Committee of the Province of Espinar commissioned the company Equas to carry out an environmental assessment. That same year, the Municipality of Espinar assessed heavy metals in sheep. All studies reported excessive levels in water, soil and air, in addition to detecting heavy metals, such as cadmium, lead, arsenic and others, in animals (CooperAcción, 2016). Yet although the detection of contamination represented progress of sorts, these processes were still not controlled by local communities, who continued to demand to play a protagonist role in monitoring water and soil quality.

In response to local demands and the 2012 conflict, the state commissioned the 2012–2013 roundtable to carry out participatory monitoring of water, air and soil. Moreover, in 2013, the first community monitoring was proposed, in which peasant communities and residents of the province would play a central role. This was an initiative of the aforementioned Vicarage of Solidarity of the Prelature of Sicuani, which became the NGO Human Rights Without Borders (in alliance with the NGO Suma Marka) and was part of an initiative to promote integrated water management in the regions of Ancash and Cusco, with the support of the Catholic Agency for Overseas Development (CAFOD) of England and Wales (CEAS, 2013). To carry out this monitoring, the methodology of the Global Water Watch (GWW) data platform was used, including the LaMotte monitoring kit, which allows the measurement of six physico-chemical parameters of water: temperature, pH, hardness, alkalinity, turbidity and dissolved oxygen. It was also decided to evaluate the same sampling points considered by the ANA and the OEFA, so that community monitoring could act as a ‘counter-sample’ and the results could be compared with the ‘official’ results of the ANA and OEFA.

The large and diverse group of volunteer monitors came from local peasant communities, leaders of social organisations, university students and other sectors. The group was trained in the use of the kit before participating in sampling. The results differed from those of the OEFA and the ANA, showing that several parameters exceeded environmental quality standards and maximum allowable limits (V.M., personal communication, 13 August 2022) and confirming to the population that their water was contaminated, which was not accepted by official bodies. Given this impact, community monitoring continued over the following years and in 2017 the monitors formally established an association with legal status, the Espinar Association of Environmental Supervisors and Monitors (AVMAE), which afforded them more autonomy to dialogue with other organisations and public entities.

Within the regulatory framework of this initiative, General Environmental Law No. 28961 recognises the establishment of Citizen Environmental Oversight Committees as an entity that contributes to the supervisory functions of the competent authority. Specifically, in the mining sector, the law provides for citizen participation during the execution phase of mining projects by way of a participatory environmental monitoring and surveillance committee. However, this participation is not mandatory (Supreme Decree No. 028-2008-EM; Ministerial Resolution 304-2008-EM). Therefore, although the AVMAE monitoring initiative aligns with the national regulatory framework, this framework does not encompass recognition of results, considering this an official matter within the purview of the competent institutions.

There have also been attempts for these community monitoring activities and their results to be recognised by the state. For example, in recent years there has been a push for the draft Law for Articulation of Environmental and Social, Citizen, and Indigenous Surveillance and Monitoring in the National Environmental Management System, which would allow incorporate these community-level committees to be articulated into the national infrastructure.

7. CBEM institutional innovations towards sustainability

The AVMAE experience led to the institutionalisation of CBEM. Currently, AVMAE conducts community monitoring with the support of Human Rights Without Borders (DHSF). Monitoring takes place four times a year, twice during the rainy season and twice during the dry season, at eight specific points distributed across three zones of the Cañipía River: upstream of the mine (3 points), the area where the mine is located (2 points) and downstream of the mine (3 points). The instrument used is still the Lamotte kit, and certain physico-chemical parameters have been added to the initial six at the initiative of the monitors, inspired by other regional monitoring experiences. In 2016, electrical conductivity and flow measurement was added, followed by aquatic and benthic macroinvertebrates in 2017.

There are three stages to the monitoring process. The first is the establishment of the monitoring plan during a meeting at the beginning of each year, led by AVAME with the support of DHSF, which sets the budget and technical experts (biologists, toxicologists, etc.) as well as the dates for monitoring and complementary activities (internships, training, etc.). The second stage is the sampling field trip, during which monitors visit the three designated zones: upstream, the project site and downstream. Each team is led by an experienced AVMAE monitor and supervised by a member of the DHSF. The AVMAE members handle the equipment, take each of the required samples and record the data. The third step is to analyse and report the results. Here, the DHSF experts support the AVMAE in interpreting the field data and preparing a final report, which is then presented and discussed with the AVMAE and finally disseminated to the general population.

Volunteer monitors are motivated to participate by their interest in learning about the state of the environment and acquiring knowledge and technical skills. One monitor explains that the aim of the AVMAE is ‘to know the state of the environment and to monitor its condition’ (N.C., personal communication, 15 August 2022). They also point out that monitoring helps give them a voice, as they learn the technical language and document evidence of environmental changes caused by mining activities. Another monitor notes that ‘monitoring shows that there is pollution from mining […]. We want to make the truth known and the mining company to assume its responsibilities, that it ‘pays the rent’, that it takes its impacts into account, for example the effects of tailings dams’ (S.C., personal communication, 10 August 2022).

A valuable aspect of monitoring is that it provides monitors with knowledge and access to alliances, enabling them to question and press for changes in state environmental governance and increase public awareness about local environmental injustice. One of the aims of the monitoring initiative is to put pressure on the state to ensure greater citizen participation in this process. Similarly, those involved in the monitoring experience see it as a way of making the state more responsive to citizens' demands. Some monitors point out, for example, that the ANA and the OEFA evaluations produce skewed results in favour of the mine, do not involve the local population, do not train community members and do not address the population's concerns about clarifying the causality of contamination and the status of heavy metal contamination (V.M., personal communication, 13 August 2022; S.C., personal communication, 10 August 2022). In response, the OEFA decided to conduct two studies in 2022: the Coroccohuayco Early Environmental Assessment and a causality study, both of which were to include training for AVMAE monitors. The OEFA acknowledges the importance of local social mobilisation in the development of its environmental monitoring: ‘the revolution of the studies was borne of the demands of the local population’ (F.G., personal communication, 19 August 2022). The importance of local participation in the production of environmental knowledge is also recognised:

What we want in this process is to involve much more citizen participation. To build our environmental assessment on the problems of the population, which was not the case before […] Now, our objectives are much more focused, because we have built them together with society (F.G., personal communication, August 26, 2022).

In this context, AVMAE monitoring does not aim to replace government environmental assessment, but rather to interweave networks and create spaces to push for better environmental assessment. One limitation the monitors recognise is the lack of financial and technical resources for complete and continuous environmental assessment encompassing air, water, sediment and heavy metal analysis (V.P., personal communication, 11 August 2022; A.S., personal communication, 18 August 2022). They cite as obstacles the lack of official state recognition of either them as an organisation capable of monitoring or the validity of their results. For this reason, they value technical training and building alliances with NGOs, foundations or universities in order to gain legitimacy and push for changes that respond to their concerns.

Another valuable advantage of CBEM is its role as an informal early warning system in case of environmental emergencies. Technical training and acquisition of scientific knowledge has enabled monitors to document contamination events reported by Espinar residents. These incidents can then be reported to the competent institution and/or broadcast through their radio station. The use of simplified terminology in the local language, Quechua, ensures that expert information can be conveyed to residents who may not have received formal training.

In Espinar, the social action mechanisms that mobilise changes in environmental governance are diverse, ranging from protests and legal actions to institutionalised actions such as community-based water monitoring. Thus, this institutional initiative has succeeded in sustaining transformative changes in its near-decade of existence. First, it has reduced knowledge inequalities, as the monitors are technically trained and acquire specialised knowledge, which leads to socio-technical empowerment of the communities. Second, the monitoring experience has promoted changes in water governance. On the one hand, it has allowed criticism to be voiced regarding the citizen participation mechanism in the design of state monitoring, and on the other hand, it promotes horizontal dialogue between experts and citizens. Finally, it promotes public awareness and recognition of the environmental injustice suffered by the local population.

8. Conclusion

This article shows that the analysed experiences of collaborative and CBEM are transformative initiatives because they challenge hegemonic resource governance in pursuit of sustainability. As Geels (Reference Geels2011) argues, they are goal-oriented. The communities involved in these innovative experiences are concerned about the negative impacts of extractive activities on the environment and quality of life. In this sense, environmental concerns relate not only to the environment in general and its ecosystems but also to the lives of communities, their productive systems and the health of present and future generations.

Moreover, these transformative initiatives are based on institutional change. The experiences of community monitoring question the current production model while also proposing alternative institutions and mechanisms to the institutional framework of environmental management. Although the experiences analysed are at different stages of institutional development, they arise from the same impulse of local actors and are both open and democratic experiences that invite community members to participate.

In line with Scoones et al. (Reference Scoones, Stirling, Abrol, Atela, Charli-Joseph, Eakin, Ely, Olsson, Pereira, Priya, van Zwanenberg and Yang2020), in both cases the role of local communities or groups has been fundamental in structuring transformative institutional innovation. Communities have sought to identify those responsible for environmental damage by challenging the extractive development model. In doing so, they have challenged the way in which the state and companies measure environmental impacts and proposed alternative monitoring systems that complement the vision of experts with the experience of local actors.

In both cases, the experiences of environmental monitoring face at least two major barriers. The first is that CBEM results are not recognised by state institutions; rather, they serve to generate information and promote dialogue with state monitoring and evaluation system. The second is that environmental monitoring (such as water and air monitoring) is expensive and requires access to funds to acquire sensors or measuring kits. It is difficult for social organisations that lead independent monitoring experiences to obtain and sustain such resources over time.

The two environmental monitoring cases also have certain specificities related to their different social contexts, power constellations, stages of institutional development and transformative goals. As Fressoli et al. (Reference Fressoli, Arond, Abrol, Smith, Ely and Dias2014) argue, different framings and interpretations of innovation are negotiated and contested in order to forge alternative pathways of innovation. In the Chilean case, civil society organisations and grassroots use the environmental monitoring initiatives to promote their national agenda for changing the air governance framework in the country, while in Peru the water monitoring initiative seeks state recognition to promote institutional changes in water governance in extractive sites from local experiences. In both cases, communities are willing to share their data and cooperate with government environmental agencies.

The different monitoring models can open up space for experimentation and other ways of producing knowledge that tend to transform existing governance mechanisms. The cases do not provide a definitive solution to social inclusion and environmental sustainability or transformation, but they do allow for the empowerment of local actors and broader access to environmental democracy. As a contribution to the literature on transformation, this article shows that the complexity of transformative initiatives lies in the ways they are embedded in and respond to specific social and environmental contexts.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/sus.2024.26.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the NGO Derechos Humanos Sin Fronteras and the Asociación de Vigilantes y Monitores Ambientales de Espinar in the Province of Espinar, Perú. Also, the authors want to thank all members of Corporación Quintero Mide in Chile, for participating in the interviews and this study.

Author contributions

G. H. D., J. G. and A. P. L. M conceived and designed the study for Perú and Chile. A. P. L. M. and E. A. Q. conducted data gathering in the case of Perú and J. G. conducted data gathering in the case of Chile. All authors participated in the analysis and writing of the cases presented.

Funding statement

This work was supported in part by the Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo de Chile, Fondo Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo (FONDECYT) N° 3200013; the Ford Foundation, Grant entitled ‘Project to promote and strengthen grassroots and CSO proposals for sustainable and inclusive development initiatives in mining regions in Colombia, Peru, and Chile through applied research’.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest related to the content of this paper.

Ethical standards

We confirm that all procedures (field work, interviews, observations) performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of each author's home institution (Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú and Universidad Autónoma de Chile), and national research committee and that informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.