1. Introduction

From mental health distress to severe water crisis, societies around the world are experiencing the impacts of human-induced climate change. In 2020, alongside these impacts, we experienced the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 has served to expose our societal vulnerabilities while also providing unique opportunities to act for a fair and climate-friendly world. With research supporting the need to develop carbon-neutral societies by 2050 to safely achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement, the need for transformative change is urgent (Head, Reference Head2020; Otto et al., Reference Otto, Donges, Cremades, Bhowmik, Hewitt, Lucht, Rockström, Allerberger, McCaffrey, Doe, Lenferna, Morán, van Vuuren and Schellnhuber2020). Enhanced understanding of the challenges facing Earth's systems – and of the social and economic consequences – contributes to identifying appropriate action.

In this paper, we carry out a horizon scan of important insights emerging from advances in integrated research related to climate change over the past year (focusing on findings published in 2019–2020). The objective of this horizon scan is twofold. First, through expert elicitation we attempt to identify the 10 most important new scientific insights over the past year. Second, this horizon scan constitutes an effort to provide an integrated synthesis of key research outputs and how these add up into broader science-based insights that should guide climate policy. This scientific horizon scan forms the basis of a wider research synthesis report on the 10 New Insights in Climate Science (10NICS) produced annually and officially handed over to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Secretariat in connection with the Conferences of Parties. Taken together, we are not claiming this to be a top-10 climate science ranking, but rather an effort of scanning the wide interdisciplinary arena of climate research and identifying key insights – and which provide evidence that is of critical importance for evidence-based policymaking.

The 10 insights begin by considering climate modelling advances and the improvements in our understanding of climate sensitivity, and regional climate predictability. In doing so, we are better placed to understand future risks and to plan for change. We then draw attention to evidence on thawing permafrost in the Arctic, which stores one-third of the world's soil carbon in a location that is responding quickly to climate change. We turn to carbon uptake by land sinks, which respond to anthropogenic change with consequences for their potential to mitigate carbon emissions. We consider how climate change will exacerbate the water crises already felt in many places, underlining how impacts depend on and contribute to social inequality. We also bring to the fore growing evidence that changing climatic conditions are adversely affecting mental health, an issue garnering attention in 2020 as it is exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. We reflect on the most urgent task for a post-COVID-19 era, namely making 2020 a turning point for reduction in global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. How our economies and societies contribute to emissions and the changes that can occur has been brought into stark relief by the lockdowns initiated to control spread of the pandemic. Following that, again in response to the pandemic, we consider the potential for COVID-19 to catalyse a new social compact for a just and climate-friendly world through strengthening inclusive forms of governance. We also underline how greening the economy through sustainable investments is cost effective and gives substantial co-benefits. This is vital given evidence showing that a primary focus on economic growth, which puts climate mitigation as a secondary goal, jeopardizes our last chance of achieving the Paris Agreement. From this we turn to energy, outlining evidence that shows how urban electrification provides a strategy to move towards low-carbon sustainable energy systems. Finally, our last insight draws attention to rights-based litigation, which clarifies the international legal standing and representation of the rights and interests of future generations in a healthy environment.

2. Methodology

The horizon scan has been overseen by an expert panel ‘Editorial Board’ with 10 researchers appointed by Future Earth, The Earth League and World Climate Research Programme (WCRP). The 10 ‘insights’ were identified through an expert elicitation process beginning with an open call for inputs, through an open-ended questionnaire for suggesting new topics. A link to the form was sent directly to 221 international experts covering a broad array of disciplines. It was also distributed to members of The Earth League, WCRP (Secretariat, Joint Scientific Committee, Core Project Chairs and Grand Challenge leaders), to international project offices and development teams of Future Earth Global Research Projects and Future Earth Knowledge-Action Networks, to Future Earth National Committees and Networks and posted on the Future Earth Open Network and Future Earth website. The questions posed to questionnaire respondents were: ‘What [do] you think are the 1–3 most important new discoveries or advancements in your overarching field of research since 1st July 2019 and the key articles and reports highlighting them[?]’.

The questionnaire resulted in 73 individual responses suggesting 128 topics. Additional 18 topics were suggested by 11 researchers via email, of which eight were unique respondents who had not answered the questionnaire. The suggested topics were summarized in 20 candidate ‘insights’. The Editorial Board identified the 10 insights that best satisfied the requirements for novelty, relevance and sufficient scientific evidence. Each insight was written by two or more experts selected from the questionnaire and the Future Earth, The Earth League and WCRP networks, based on qualifications and quality of topic suggestions. All authors were approved by the Editorial Board.

Further details on methodology can be found in Supplementary materials.

3. New insights

3.1. Climate sensitivity and predictability are now better understood

At the centre of international climate change negotiations are the rising concentration of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere. CO2 is the most significant anthropogenic GHG being emitted into the atmosphere, reducing emissions of terrestrial radiation to space and causing global temperatures to rise. Although this understanding pre-dates the 20th century, the quantitative relationship between CO2 levels and global warming has remained uncertain for decades, hampering efforts to understand future risks and plan for change.

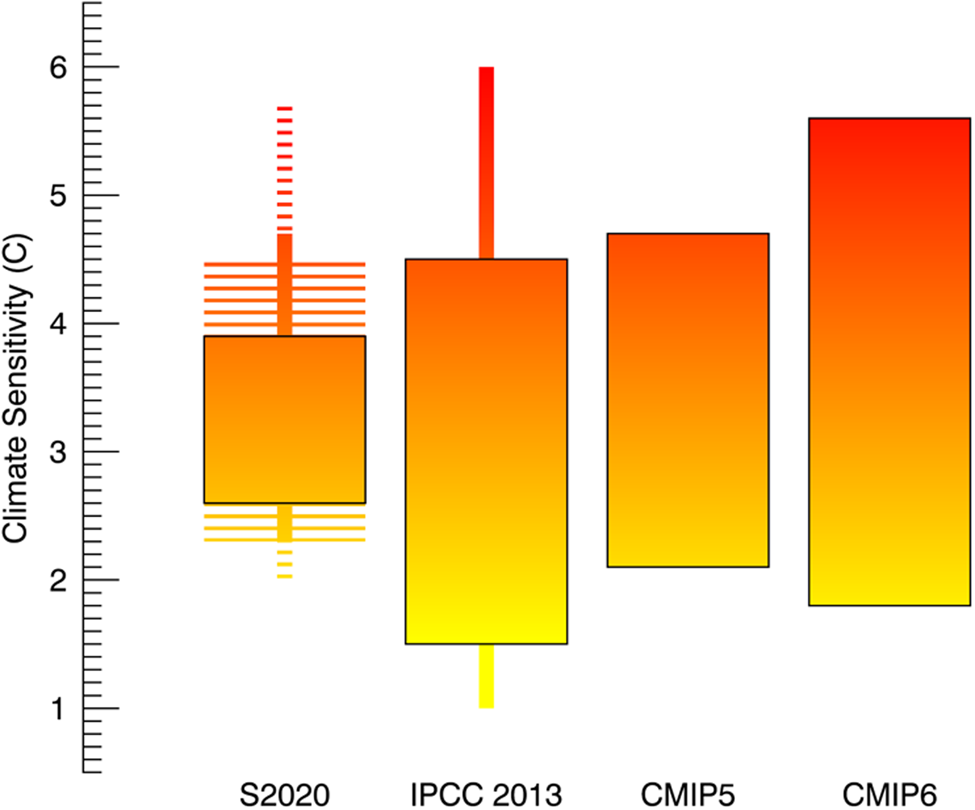

The ‘likely range’ (at least a 66% chance of being within this range) of equilibrium climate sensitivity – the long-term global rise in air temperature expected as a result of doubling atmospheric CO2 concentrations – was estimated to be 1.5–4.5°C by Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, Reference Stocker, Qin, Plattner, Tignor, Allen, Boschung, Nauels, Xia, Bex and Midgley2013) in its Fifth Assessment Report (AR5); these figures remained unchanged since the Charney report of 1979.

Larger climate sensitivity is suggested by global-scale climate change experiments carried out using the latest Earth System Models and coordinated under the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6), which exhibit sensitivity values ranging from 1.8 to 5.6°C. The values of 10 models exceeded the upper end of the aforementioned likely range. The higher climate sensitivity seen in many models is due primarily to stronger amplifying cloud feedbacks from low clouds at middle and high latitudes (Flynn & Mauritsen, Reference Flynn and Mauritsen2020; Zelinka et al., Reference Zelinka, Myers, McCoy, Po-Chedley, Caldwell, Ceppi, Klein and Taylor2020). This may be related to improvements in how models decide whether cold clouds are made of liquid or ice water, a difficult problem (Bodas-Salcedo et al., Reference Bodas-Salcedo, Mulcahy, Andrews, Williams, Ringer, Field and Elsaesser2019; Gettelman et al., Reference Gettelman, Hannay, Bacmeister, Neale, Pendergrass, Danabasoglu, Lamarque, Fasullo, Bailey, Lawrence and Mills2019). But even though a priori these changes seem to be improvements, many high-sensitivity models overestimate recent warming trends (Nijsse et al., Reference Nijsse, Cox and Williamson2020; Tokarska et al., Reference Tokarska, Stolpe, Sippel, Fischer, Smith, Lehner and Knutti2020), suggesting that the higher sensitivity models should be treated with caution.

Indeed, the likely range of climate sensitivity has now been narrowed to 2.3–4.5°C by a new, comprehensive WCRP analysis of the broader evidence (Sherwood et al., Reference Sherwood, Webb, Annan, Armour, Forster, Hargreaves, Hegerl, Klein, Marvel, Rohling, Watanabe, Andrews, Braconnot, Bretherton, Foster, Hausfather, von der Heydt, Knutti, Mauritsen and Zelinka2020). This took a three-pronged approach of examining climate feedback processes, the historical record and the palaeoclimate record, which all provided evidence against the high model climate sensitivities (Sherwood et al., Reference Sherwood, Webb, Annan, Armour, Forster, Hargreaves, Hegerl, Klein, Marvel, Rohling, Watanabe, Andrews, Braconnot, Bretherton, Foster, Hausfather, von der Heydt, Knutti, Mauritsen and Zelinka2020). In particular, they find that sensitivities above 4.5°C are hard to reconcile with palaeoclimate evidence, also noted by Zhu et al. (Reference Zhu, Poulsen and Otto-Bliesner2020). On the other hand, Sherwood et al. (Reference Sherwood, Webb, Annan, Armour, Forster, Hargreaves, Hegerl, Klein, Marvel, Rohling, Watanabe, Andrews, Braconnot, Bretherton, Foster, Hausfather, von der Heydt, Knutti, Mauritsen and Zelinka2020) find that the likely range does not extend below 2.3°C, which discounts the lower end of the IPCC AR5 range. This conclusion was supported by all lines of evidence and indicates that moderate emissions reduction scenarios are less likely to meet the Paris temperature targets than previously anticipated (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Climate sensitivity ranges from recent sources. First entry shows 66% (thick bar) and 90% (thin bar) probability ranges from Sherwood et al. (Reference Sherwood, Webb, Annan, Armour, Forster, Hargreaves, Hegerl, Klein, Marvel, Rohling, Watanabe, Andrews, Braconnot, Bretherton, Foster, Hausfather, von der Heydt, Knutti, Mauritsen and Zelinka2020), with hatched extensions bounding the span of these ranges under plausible alternative assumptions. The second bar shows the 66%-or-greater (thick bar) and 90%-or-greater (thin bar) probability ranges from IPCCs AR5 report in 2013. The third and fourth bars show the full span of values predicted by the previous and current generation of global climate models respectively. All values are ‘effective’ climate sensitivities except that IPCCs is formally given as an equilibrium value; the particular definition has a 5%-or-less impact on probability ranges (Sherwood et al., Reference Sherwood, Webb, Annan, Armour, Forster, Hargreaves, Hegerl, Klein, Marvel, Rohling, Watanabe, Andrews, Braconnot, Bretherton, Foster, Hausfather, von der Heydt, Knutti, Mauritsen and Zelinka2020).

On regional scales, climate models are also becoming better at simulating temperature and hydrological extremes (Di Luca et al., Reference Di Luca, Pitman and de Elía2020; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Min, Zhang, Sillmann and Sandstad2020), including the intensity of heavy rainfall events (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Min, Zhang, Sillmann and Sandstad2020) and hot and cold extremes (Di Luca et al., Reference Di Luca, Pitman and de Elía2020). Models are now able to simulate rainfall droughts well, particularly at the seasonal scale and the projections of drought duration and frequency are becoming more consistent over many regions (Ukkola et al., Reference Ukkola, De Kauwe, Roderick, Abramowitz and Pitman2020). Although regional changes in mean rainfall remain uncertain, this provides new opportunities for water resource management.

In the near term, climate models are better able to predict the observed evolution of regional climate than previously thought possible, particularly around the Atlantic Basin. Decadal predictions of the atmospheric circulation and regional temperature and rainfall all now show encouraging levels of skill and this offers great promise for the utility of regional climate predictions. However, climate models also show a spuriously low ratio of predictable signal strength to internal noise variability. This means that newfound decadal prediction skill can only be realized by averaging large ensembles of hundreds of simulations and it could affect the attribution and prediction of quantitative changes in extratropical climate using current models (Scaife & Smith, Reference Scaife and Smith2018; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Scaife, Eade, Athanasiadis, Bellucci, Bethke, Bilbao, Borchert, Caron, Counillon, Danabasoglu, Delworth, Doblas-Reyes, Dunstone, Estella-Perez, Flavoni, Hermanson, Keenlyside, Kharin and Zhang2020).

3.2. Greenhouse gas emissions from permafrost will be larger due to abrupt thaw processes

Thawing permafrost in the Arctic is expected to release significant quantities of GHGs over the coming decades, enough to merit consideration in climate negotiations. Recent research shows it will be larger than earlier projections due to abrupt permafrost thaw processes (Turetsky et al., Reference Turetsky, Abbott, Jones, Anthony, Olefeldt, Schuur, Grosse, Kuhry, Hugelius, Koven, Lawrence, Gibson, Sannel and McGuire2020).

Permafrost is a perpetually frozen layer beneath the seasonally thawed surface layer of the ground. The northern permafrost region covers 18 million km2 and stores 1460–1600 petagrams of carbon (PgC) – one-third of the world's soil carbon (Meredith et al., Reference Meredith, Sommerkorn, Cassotta, Derksen, Ekaykin, Hollowed, Kofinas, Mackintosh, Melbourne-Thomas, Muelbert, Ottersen, Pritchard, Schuur, Pörtner, Roberts, Masson-Delmotte, Zhai, Tignor, Poloczanska, Mintenbeck, Alegría, Nicolai, Okem, Petzold, Rama and Weyer2019). The Arctic is responding quickly to climate change, with air temperatures warming more than twice as fast as the global average. Unusually warm summers – such as the record-breaking 2020 heatwave in Siberia and Svalbard – are happening more often (Ciavarella et al., Reference Ciavarella, Cotterill, Stott, Kew, Philip, van Oldenborgh, Skålevåg, Lorenz, Robin, Otto, Hauser, Seneviratne, Lehner, Shirshov and Zolina2020). This is causing Arctic permafrost to thaw in some northern regions almost a century earlier than some climate models projected (Farquharson et al., Reference Farquharson, Romanovsky, Cable, Walker, Kokelj and Nicolsky2019).

Abrupt permafrost thaw happens when melting ground ice causes the ground surface above to collapse. This liberates previously frozen soil carbon, creating a so-called ‘thermokarst’ landscape of slumps and gullies in upland areas and collapse-scar wetlands and lakes in less well-drained areas. Satellite observations of these landscape-scale changes have shown an acceleration in abrupt thaw processes over the past two decades; they are expected to substantially increase this century as climate warms (Lewkowicz & Way, Reference Lewkowicz and Way2019).

Although climate models do include gradual permafrost thaw, they do not include the more complex thermokarst-inducing processes. When thermokarst is included, by the year 2100 up to three times more carbon becomes exposed assuming a moderate emission scenario at Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) 4.5 and up to 12 times more carbon is exposed under a high emission scenario of RCP8.5 (Nitzbon et al., Reference Nitzbon, Westermann, Langer, Martin, Strauss, Laboor and Boike2020).

Abrupt permafrost thaw increases thaw rates and also causes ecosystem shifts to conditions more conducive to producing strong GHG emissions, notably methane. The IPCC Special Report 1.5 estimated 27 PgC of cumulative carbon emissions from permafrost thaw and wetlands by 2100 for low emission scenarios (where PgC is carbon loss in CO2 equivalents). The more recent studies indicate that under moderate and high emission scenarios (RCP4.5–RCP8.5), emissions from abrupt thaw processes would approximately double the projected cumulative carbon emissions compared to estimates of gradual thaw alone (Gasser et al., Reference Gasser, Kechiar, Ciais, Burke, Kleinen, Zhu, Huang, Ekici and Obersteiner2018; Turetsky et al., Reference Turetsky, Abbott, Jones, Anthony, Olefeldt, Schuur, Grosse, Kuhry, Hugelius, Koven, Lawrence, Gibson, Sannel and McGuire2020). Increased losses through abrupt thaw may also apply to emission scenarios consistent with 1.5- or 2-degree warming targets but these more aggressive climate change mitigation pathways could halve abrupt thaw carbon losses compared to high emission pathways (Figure 2).

Fig. 2. Thawing coastal permafrost in Arctic Canada with person for scale. Credit: G. Hugelius.

Peatlands have year-round waterlogged conditions that slow plant decomposition, allowing peat to accumulate – one of the largest natural carbon stores on land. Nearly half of northern peatlands are underlain by permafrost. Abrupt thaw could shift the entire northern hemisphere peatland carbon sink into a net source of global warming, dominated by methane, lasting several centuries (Hugelius et al., Reference Hugelius, Loisel, Chadburn, Jackson, Jones, MacDonald, Marushchak, Olefeldt, Packalen, Siewert, Treat, Turetsky, Voigt and Yu2020).

Most of the methane emissions from thawing permafrost are fuelled by recently stored carbon, rather than carbon sequestered thousands of years ago (Dean, Reference Dean2020; Dean et al., Reference Dean, Meisel, Rosco, Marchesini, Garnett, Lenderink, van Logtestijn, Borges, Bouillon, Lambert, Röckmann, Maximov, Petrov, Karsanaev, Aerts, van Huissteden, Vonk and Dolman2020). A study of atmospheric methane over the past million years of Earth's history, using ice cores from Antarctica, found no evidence for substantial releases of methane due to the destabilization of old permafrost carbon stores (Dyonisius et al., Reference Dyonisius, Petrenko, Smith, Hua, Yang, Schmitt, Beck, Seth, Bock, Hmiel, Vimont, Menking, Shackleton, Baggenstos, Bauska, Rhodes, Sperlich, Beaudette, Harth and Weiss2020). This is because when methane is produced at depth in thawing soils or sediments, microorganisms living in the soil or water columns above oxidize most of the methane before it reaches the surface, instead releasing it as CO2 (Dean, Reference Dean2020).

An ecological feedback associated with permafrost thaw that is not yet included in global climate models is a priming effect on soil respiration, caused by an increase in root activity. This amplifies soil carbon loss, with an additional 40 PgC loss projected from Arctic permafrost by 2100 for RCP8.5 (Keuper et al., Reference Keuper, Wild, Kummu, Beer, Blume-Werry, Fontaine, Gavazov, Gentsch, Guggenberger, Hugelius, Jalava, Koven, Krab, Kuhry, Monteux, Richter, Shahzad, Weedon and Dorrepaal2020).

In summary, when adding new knowledge on abrupt thaw to what's currently modelled for gradual thaw, the expected carbon emissions from permafrost could as much as double by year 2100. The carbon emissions from permafrost regions could be even higher when including effects on root activity which increase soil decomposition. Accounting for these effects will impose tighter restrictions on the remaining anthropogenic carbon emission budgets.

3.3. Carbon uptake by land sinks – potentials and limits

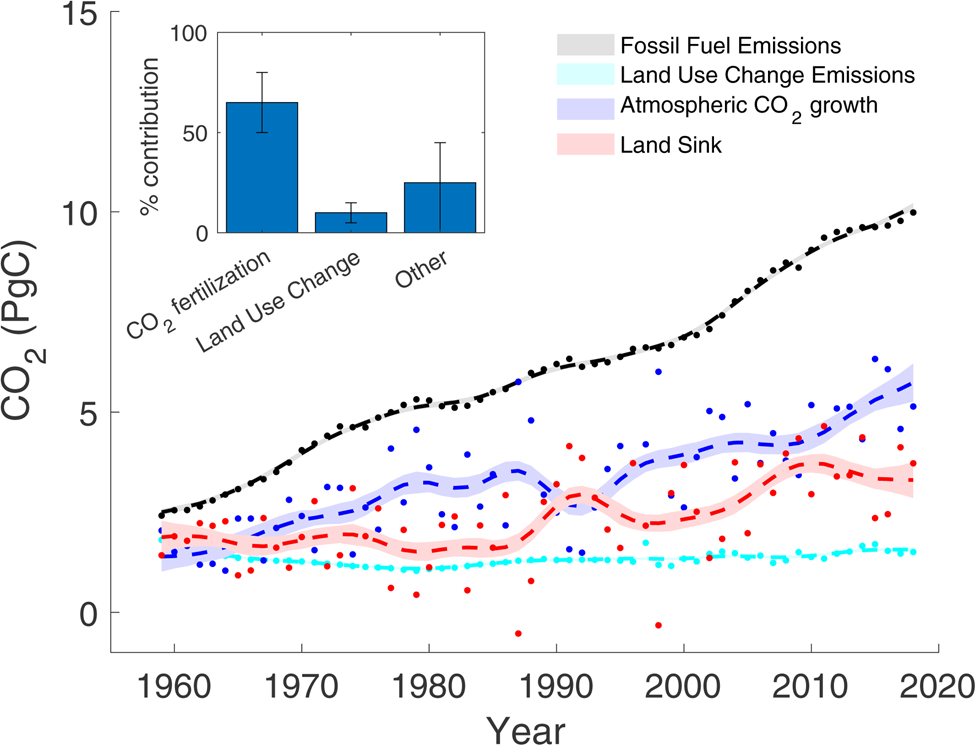

Land ecosystems remove about 30% of the CO2 emitted through fossil fuels and land-use change (LUC) emissions, an ecosystem service referred to as the ‘(natural) land sink’ (see Figure 3; Friedlingstein et al., Reference Friedlingstein, Jones, O'Sullivan, Andrew, Hauck, Peters, Peters, Pongratz, Sitch, Le Quéré, Bakker, Canadell, Ciais, Jackson, Anthoni, Barbero, Bastos, Bastrikov, Becker and Zaehle2019). This serves to slow the growth rate of atmospheric CO2, and consequently reduces the rate of climate change. The amount of CO2 absorbed by the land has also increased rapidly over the past few decades, likewise to anthropogenic CO2 emissions it has more than doubled since 1960 (Friedlingstein et al., Reference Friedlingstein, Jones, O'Sullivan, Andrew, Hauck, Peters, Peters, Pongratz, Sitch, Le Quéré, Bakker, Canadell, Ciais, Jackson, Anthoni, Barbero, Bastos, Bastrikov, Becker and Zaehle2019) with extensive greening reported (Piao et al., Reference Piao, Wang, Park, Chen, Lian, He, Bjerke, Chen, Ciais, Tømmervik, Nemani and Myneni2020) as well as large associated changes in the effect vegetation has on local and global climate (Forzieri et al., Reference Forzieri, Miralles, Ciais, Alkama, Ryu, Duveiller, Zhang, Robertson, Kautz, Martens, Jiang, Arneth, Georgievski, Li, Ceccherini, Anthoni, Lawrence, Wiltshire, Pongratz and Cescatti2020). The increased land sink has occurred despite an increased prevalence of large-scale natural disruptions to ecosystems (McDowell et al., Reference McDowell, Allen, Anderson-Texeira, Aukema, Bond-Lamberty, Chini, Clark, Dietze, Grossiord, Hanbury-Brown, Hurtt, Jackson, Johnson, Kueppers, Lichstein, Ogle, Poulter, Pugh, Seidl and Xu2020) and evidence that some of the largest carbon sinks of the planet have already saturated (Hubau et al., Reference Hubau, Lewis, Phillips, Affum-Baffoe, Beeckman, Cuní-Sanchez, Daniels, Ewango, Fauset, Mukinzi, Sheil, Sonké, Sullivan, Sunderland, Taedoumg, Thomas, White, Abernethy, Adu-Bredu and Zemagho2020). Its increase is stronger than changes in emissions from LUCs (Friedlingstein et al., Reference Friedlingstein, Jones, O'Sullivan, Andrew, Hauck, Peters, Peters, Pongratz, Sitch, Le Quéré, Bakker, Canadell, Ciais, Jackson, Anthoni, Barbero, Bastos, Bastrikov, Becker and Zaehle2019) but largely undermined by the impact of LUC on tropical ecosystems (Tagesson et al., Reference Tagesson, Schurgers, Horion, Ciais, Tian, Brandt, Ahlström, Wigneron, Ardö, Olin, Fan, Wu and Fensholt2020). The natural land sink is not constant, however, and responds directly to environmental changes, such as heatwaves and droughts (Bastos et al., Reference Bastos, Ciais, Friedlingstein, Sitch, Pongratz, Fan, Wigneron, Weber, Reichstein, Fu, Anthoni, Arneth, Haverd, Jain, Joetzjer, Knauer, Lienert, Loughran, McGuire and Zaehle2020), and anthropogenic interventions such as deforestation and LUC (Brando et al., Reference Brando, Soares-Filho, Rodrigues, Assunção, Morton, Tuchschneider, Fernandes, Macedo, Oliveira and Coe2020). The dynamic nature of terrestrial carbon uptake makes understanding the regional hotspots of source or sink potential – and the processes that dictate the likelihood of continued increased uptake in those regions – essential for adequate policy design.

Fig. 3. Long-term trajectories of the residual land sink, along with the atmospheric CO₂ growth rate and emissions from fossil fuel burning and land use. The inset attributes the long-term changes in the sink to the percentage contribution of CO2 fertilization, LUC and other (e.g. N-deposition, ozone and phenology) factors (data from Tharammal et al., Reference Tharammal, Bala, Devaraju and Nemani2019).

CO2 fertilization is widely reported to be the primary cause of the increased land sink (Tharammal et al., Reference Tharammal, Bala, Devaraju and Nemani2019; Walker et al., Reference Walker, De Kauwe, Bastos, Belmecheri, Georgiou, Keeling, McMahon, Medlyn, Moore, Norby, Zaehle, Anderson-Teixeira, Battipaglia, Brienen, Cabugao, Cailleret, Campbell, Canadell, Caias and Zuidema2020). Rising atmospheric CO2 increases leaf-scale photosynthesis and resource-use efficiencies, which can lead to increased plant growth, vegetation biomass and soil organic matter. However, due to the complexity and heterogeneity of ecosystems, the resulting impact of CO2 on carbon uptake is context dependent. Particularly, nutrient availability constrains the ability of global ecosystems to translate increased photosynthesis into increased biomass and thus carbon storage (Terrer et al., Reference Terrer, Jackson, Prentice, Keenan, Kaiser, Vicca, Fisher, Reich, Stocker, Hungate, Peñuelas, McCallum, Soudzilovskaia, Cernusak, Talheim, Van Sundert, Piao, Newton, Hovenden and Franklin2019). The CO2 fertilization and other effects beneficial for carbon uptake are further offset by the detrimental impact of warming on soil carbon (Vaughn & Torn, Reference Vaughn and Torn2019) and permafrost (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Yang, Yang, Piao, Li, Cheng and Fu2020a), and regional increases in forest mortality due to changes in the frequency of extreme events (McDowell et al., Reference McDowell, Allen, Anderson-Texeira, Aukema, Bond-Lamberty, Chini, Clark, Dietze, Grossiord, Hanbury-Brown, Hurtt, Jackson, Johnson, Kueppers, Lichstein, Ogle, Poulter, Pugh, Seidl and Xu2020). A recent report suggests that CO2 fertilization effects on vegetation photosynthesis are globally declining as a result of these and other offsetting factors such as water and nutrient limitations (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhang, Ju, Chen, Ciais, Cescatti, Sardans, Janssens, Wu, Berry, Campbell, Fernández-Martínez, Alkama, Sitch, Friedlingstein, Smith, Yuan, He, Lombardozzi and Peñuelas2020c).

The processes that offset CO2 fertilization are highly regionally specific, and emerging evidence suggests that many tropical regions are at or near sink saturation (Hubau et al., Reference Hubau, Lewis, Phillips, Affum-Baffoe, Beeckman, Cuní-Sanchez, Daniels, Ewango, Fauset, Mukinzi, Sheil, Sonké, Sullivan, Sunderland, Taedoumg, Thomas, White, Abernethy, Adu-Bredu and Zemagho2020), while boreal and temperate zones continue to increase their sink capacity (Tagesson et al., Reference Tagesson, Schurgers, Horion, Ciais, Tian, Brandt, Ahlström, Wigneron, Ardö, Olin, Fan, Wu and Fensholt2020). LUC impacts explain much of the regional differences with deforestation in tropical regions (Brando et al., Reference Brando, Soares-Filho, Rodrigues, Assunção, Morton, Tuchschneider, Fernandes, Macedo, Oliveira and Coe2020) and increased wood harvesting in Europe (Ceccherini et al., Reference Ceccherini, Duveiller, Grassi, Lemoine, Avitabile, Pilli and Cescatti2020). Moreover, unprecedented carbon losses also occurred due to fires in Australia, California, the Amazon and the Arctic, with fire impacts predicted to worsen as a result of anthropogenic climate change (Bowman et al., Reference Bowman, Kolden, Abatzoglou, Johnston, van der Werf and Flannigan2020; Witze Reference Witze2020). Although results for the world's drylands are currently inconclusive, recent reports suggest that previous long-term aridity-change projections overestimated dryland aridification (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Roderick, Zhang, McVicar and Donohue2019).

Several knowledge gaps exist regarding the future potential of the land sink to offset carbon emissions. Although the effect of CO2 on global ecosystem productivity is now widely acknowledged, the estimated magnitude of the effect spans an order of magnitude across studies (Walker et al., Reference Walker, De Kauwe, Bastos, Belmecheri, Georgiou, Keeling, McMahon, Medlyn, Moore, Norby, Zaehle, Anderson-Teixeira, Battipaglia, Brienen, Cabugao, Cailleret, Campbell, Canadell, Caias and Zuidema2020), which greatly hinders the ability of models to project future expected changes. On large scales the natural land sink can be measured only concurrently with CO2 sinks and sources due to land-use activities. Better quantification of the net LUC flux is thus key for a better understanding of the natural land sink. Land management is an important unknown, and practices that co-deliver food security, climate change mitigation and combat land-degradation and desertification are needed (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Calvin, Nkem, Campbell, Cherubini, Grassi, Korotkov, Hoang, Lwasa, McElwee, Nkonya, Saigusa, Soussana, Taboada, Manning, Nampanzira, Arias-Navarro, Vizzarri, House and Arneth2019). Although effective practices could potentially achieve up to 30% of mitigation targets needed to limit warming to 1.5°C (Roe et al., Reference Roe, Streck, Obersteiner, Frank, Griscom, Drouet, Fricko, Gusti, Harris, Hasegawa, Hausfather, Havlík, House, Nabuurs, Popp, Sánchez, Sanderman, Smith and Stehfest2019), proposed approaches based on widespread afforestation need to recognize the potential negative impacts of tree planting, such as habitat loss and interference with naturally treeless ecosystems (Bond et al., Reference Bond, Stevens, Midgley and Lehmann2019). Funding mechanisms for such natural solution approaches are also needed, with renewed calls for carbon tax strategies to support land-based mitigation (Barbier et al., Reference Barbier, Lozano, Rodríguez and Troëng2020).

In summary, although we currently see a substantial and slightly increasing land carbon sink, there is evidence of a weakening sink capacity as the effects of drought and warming start to outweigh CO2 fertilization effects (Figure 3).

3.4. Climate change will severely exacerbate the water crisis

Climate change is already causing extreme events in many watersheds, impacting communities (Madakumbura et al., Reference Madakumbura, Kim, Utsumi, Shiogama, Fischer, Seland, Scinocca, Mitchell, Hirabayashi and Oki2019). Changes in extreme precipitation are likely to be stronger than changes in mean precipitation, with extreme events increasing in intensity and frequency (Myhre et al., Reference Myhre, Alterskjær, Stjern, Hodnebrog, Marelle, Samset, Sillmann, Schaller, Fischer, Schulz and Stohl2019). Extreme precipitation will increase over all climate regions, but with greater intensity in humid and semi-humid regions compared to semi-arid areas, with a corresponding change in flood risk – overall flood intensity is also projected to increase for most areas (Tabari et al., Reference Tabari, Hosseinzadehtalaei, AghaKouchak and Willems2019). Changes in precipitation impact spatio-temporal distribution and water availability, with seasonally variable rainfall regimes anticipated to become even more variable, whereas regimes with low seasonal variation will receive more rainfall in the monsoon (Konapala et al., Reference Konapala, Mishra, Wada and Mann2020). There is likely to be an increase in the aridity of 72% of land area which, even when accounting for vegetation response to the increased CO2 levels, is expected to have deleterious effects on ecosystems and their ability to sustain life. This particularly affects the Middle East, North Africa, south Europe and Australia (Tabari et al., Reference Tabari, Hosseinzadehtalaei, AghaKouchak and Willems2019). Urbanization is further altering regional climate patterns – for instance increasing the magnitude and recurrence of extreme precipitation events in large urban areas in China (Li et al., Reference Li, Zhao, Scaioni, Hosseini, Wang, Yao, Zhang, Gao and Li2019). Climate hazards will drive water scarcity due to physical shortage, or scarcity in access due to the failure of institutions to ensure a regular supply or because of a lack of adequate infrastructure (Empinotti et al., Reference Empinotti, Budds and Aversa2019).

Extreme events are very important drivers of water crises, however, current practice in general circulation models may understate the potential for significant changes in the hydrological cycle including the risk of extreme events (Hamstead & Coseo, Reference Hamstead, Coseo, Smith and Ram2020; Lomba-Fernández et al., Reference Lomba-Fernández, Hernantes and Labaka2019; Nicklin et al., Reference Nicklin, Leicher, Dieperink and Van Leeuwen2019), for instance by focusing on the ensemble mean and variance (Tegegne & Melesse, Reference Tegegne and Melesse2020). Changes in extreme precipitation require greater attention in climate modelling and prediction research. There is greatest global uncertainty in tropical and subtropical regions because of a combination of the difficulty in modelling convective rainstorms and the sparsity of weather observation networks for model validation and refinement (Tabari et al., Reference Tabari, Hosseinzadehtalaei, AghaKouchak and Willems2019).

Climate change coupled with socioeconomic drivers can also impact water quality – for instance shifts in monsoon timings can lead to dilution or concentration of nitrogen, phosphorus and other pollutants (Whitehead et al., Reference Whitehead, Jin, Bussi, Voepel, Darby, Vasilopoulos, Manley, Rodda, Hutton, Hackney, Van Pham Dang Tri and Hung2019). Conversely, water quality and pollution levels can impact the ability of sensitive ecosystems such as coral reefs to recover from extreme climate events (MacNeil et al., Reference MacNeil, Mellin, Matthews, Wolff, McClanahan, Devlin, Drovandi, Mengersen and Graham2019).

The Cape Town water crisis has been a clear example of a water insecurity event that is indicative of how extreme climatic events are exacerbated by climate change. In 2018 Cape Town went through a severe water crisis as a result of a multi-year drought. Shepherd (Reference Shepherd2019) reviewed how the city responded to the threat of ‘Day Zero’ for the urban supply, the moment when the reservoirs might run dry. The water crisis in Cape Town has complex political and social ramifications, both reinforcing existing inequalities and increasing competition between water users, but also opening up new potentials for solidarity and collective action. Water conservation efforts, particularly the city's creative campaign to reduce demand among residents and businesses, reduced the severity of water scarcity (Simpson et al., Reference Simpson, Shearing and Dupont2020; Van Zyl & Jooste, Reference Van Zyl and Jooste2020).

The impacts of water crises and climate risks are highly unequal, driven by social inequality (Craig et al., Reference Craig, Feng and Gilbertz2019; Roshan & Kumar, Reference Roshan and Kumar2020; WWAP, 2020). A review of water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) and gender linkages shows that this highly unequal impact of inadequate water supply is the rule (Pouramin et al., Reference Pouramin, Nagabhatla and Miletto2020). Inadequate WASH resources disproportionately affect women and girls, leading to negative health outcomes in 71% of the studies reviewed.

Finally, there is increasing policy recognition that water-related extreme events are also contributing to the migration and displacement of millions of people. A new United Nations (UN) report documents these cases and suggests that rather than trying to prevent climate-driven migration, the international policy community should begin considering migration as a potential adaptation strategy, one that can help in achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Nagabhatla et al., Reference Nagabhatla, Pouramin, Brahmbhatt, Fioret, Glickman, Newbold and Smakhtin2020). Migration, urbanization and climate change are disruptors that can catalyse shifts in values towards water use and management (IPBES, Reference Brondizio, Settele, Díaz and Ngo2019). Integrated climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies could be a win–win policy: it could concurrently combat both the causes and impacts of climate change, thus help tackle water crises and disaster risk in tandem (WWAP, 2020).

3.5. Climate change can profoundly affect our mental health

Climate change is contributing to increased injuries, illnesses and deaths, with health risks projected to increase as temperatures, precipitation and other climatic variables continue to change (Haines et al., Reference Haines, Ebi, Smith and Woodward2014). There is growing evidence that changing climatic conditions are adversely affecting mental health including states of mental wellness, emotional resilience and psychosocial well-being (see e.g. Basu et al., Reference Basu, Gavin, Pearson, Ebisu and Malig2018; Hanigan, Schirmer and Niyonsenga, Reference Hanigan, Schirmer and Niyonsenga2018). These affects can become severe when people experience the consequences of cascading and compounding risks, such as heatwaves coincident with wildfires. Climate hazards can result in new or worsened stress and clinical disorders such as trauma, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and depression (Hayes, Berry & Ebi, Reference Hayes, Berry and Ebi2019; Middleton et al., Reference Middleton, Cunsolo, Jones-Bitton, Shiwak, Wood, Pollock, Flowers and Harper2020; Wu, Snell & Samji, Reference Wu, Snell and Samji2020). Some studies describe increased risk of suicide related to exposure to warming temperatures (Burke et al., Reference Burke, González, Baylis, Heft-Neal, Baysan, Basu and Hsiang2018b).

In 2016, it was estimated that mental and addictive disorders affected more than 1 billion people globally (Rehm & Shield, Reference Rehm and Shield2019) but accurate statistics are lacking. Growing public awareness of the current impacts and future risks of changing climate and weather patterns, wildfires, sea level rise and ocean acidification are increasing the prevalence of emotional responses, especially among youth concerned about the future (Clayton, Reference Clayton2020). Terms used to describe this phenomenon include eco-anxiety, biospheric concern and solastalgia (Cianconi, Betrò & Janiri, Reference Cianconi, Betrò and Janiri2020). It is expected that rising sea levels and coastal erosion and other climate impacts will contribute to relocation, displacement and migration away from high-risk human settlements (McMichael et al., Reference McMichael, Dasgupta, Ayeb-Karlsson and Kelman2020; Palinkas & Wong, Reference Palinkas and Wong2020). The associated disruption of community networks, livelihoods and place attachment can lead to heightened psychosocial risks (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Poland, Cole and Agic2020).

Tackling climate-related mental health issues requires proactive planning with (inter)national agreements, preparedness building activities but also displacement, migration and mental health support for those on the move or ‘left behind’ (Matias, Reference Matias2020; Schwerdtle, Bowen & McMichael, Reference Schwerdtle, Bowen and McMichael2018). Health-system resilience also needs to be strengthened to include mental health support for survivors of climate-related disasters, including the mental health impacts that can last years from living in temporary shelters over prolonged periods of time or enduring the lengthy reconstruction of settlements (Schwartz et al., Reference Schwartz, Liu, Lieberman-Cribbin and Taioli2017; Yokoyama et al., Reference Yokoyama, Otsuka, Kawakami, Kobayashi, Ogawa, Tannno, Onoda, Yaegashi and Sakata2014). Figure 4 shows a comprehensive list with factors influencing mental health, and how mental health, well-being and emotional resilience can be improved (Hayes, Berry & Ebi, Reference Hayes, Berry and Ebi2019). In order to better understand the risks to mental health arising from climate change, it is important to support transdisciplinary research and practice collaborations (Hayes, Berry & Ebi, Reference Hayes, Berry and Ebi2019).

Fig. 4. Factors that influence the psychosocial health impacts of climate change. A framework showing the mental health consequences of climate change and how these consequences are mediated by the social and ecological determinants of health, response interventions and factors that influence psychosocial adaptation when they are in place or when absent act as barriers to psychosocial adaptation. Adapted with permission from Hayes, Berry, and Ebi (Reference Hayes, Berry and Ebi2019).

A large body of research identifies strategies for addressing mental health and improving emotional resilience (Hayes & Poland, Reference Hayes and Poland2018; Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Blashki, Wiseman, Burke and Reifels2018). Such strategies will need to be harnessed and adapted to address current and future mental health risks and impacts of climate change. Concrete actions include communicating with individuals and populations about climate change and mental health; advocacy for GHG reductions and adaptation measures that enable populations to cope with, prepare for and respond to climatic risks. In this regard, governmental acknowledgment of mental ill-health as a worrying and increasing burden of disease is growing (McIver et al., Reference McIver, Kim, Woodward, Hales, Spickett, Katscherian, Hashizume, Honda, Kim, Iddings, Naicker, Bambrick, McMichael, Ebi and L2016; Rehm & Shield, Reference Rehm and Shield2019).

Policies and measures to protect and strengthen blue and green spaces (i.e. visible waters and greenery, respectively) are important as the ecosystem services they provide are associated with positive mental health and well-being outcomes (Bratman et al., Reference Bratman, Anderson, Berman, Cochran, de Vries, Flanders, Folke, Frumkin, Gross, Hartig, Kahn, Kuo, Lawler, Levin, Lindahl, Meyer-Lindenberg, Mitchell, Ouyang, Roe and Daily2019). For example, the presence of green space during childhood has been associated with better mental health later in life (Engemann et al., Reference Engemann, Pedersen, Arge, Tsirogiannis, Mortensen and Svenning2019). Likewise, short, frequent walks or time spent in blue spaces have proven mental health benefits (Vert et al., Reference Vert, Gascon, Ranzani, Márquez, Triguero-Mas, Carrasco-Turigas, Arjona, Koch, Llopis, Donaire-Gonzalez, Elliott and Nieuwenhuijsen2020). Ecosystem service assessments and policies, land-use decisions and climate change resilience plans need to include psychosocial well-being considerations. Such considerations are also fundamental components of climate-resilient development and have multiple benefits – for human health and the health of our natural environment.

In sum, climate change can profoundly affect mental health. Cascading and compounding risks are projected to increase, contributing to anxiety and distress. There are opportunities to address the mental health consequences of climate change, including by implementing and communicating effective mitigation and adaptation strategies (such as blue and green spaces), protecting ecosystems and biodiversity with resultant co-benefits for human health, as well as developing mental health support strategies.

This insight is further elaborated on in the Supplementary material.

3.6. Many governments are missing the opportunity to use COVID-19 recovery spending for decarbonization

In the first half of 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic led to widespread confinement and human mobility restrictions, resulting in economic contraction and reduced emissions of GHGs and air pollutants. For this period, global CO2 emissions were estimated to decline by 8.8% compared to 2019 (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Ciais, Deng, Lei, Davis, Feng, Zheng, Cui, Dou, Zhu, Guo, Ke, Sun, Lu, He, Wang, Yue, Wang, Lei and Schellnhuber2020). This included a CO2 emission decline of 17% at days of peak lockdown (Le Quéré et al., Reference Le Quéré, Jackson, Jones, Smith, Abernethy, Andrew, De-Gol, Willis, Shan, Canadell, Friedlingstein, Creutzig and Peters2020) and a nitrogen oxides (NOx) decline of 30% (Forster et al., Reference Forster, Forster, Evans, Gidden, Jones, Keller, Lamboll, Le Quéré, Rogelj, Rosen, Schleussner, Richardson, Smith and Turnock2020) in April. The transport sector was responsible for roughly half of the decline, while industry and the power sector yielded another 43%. Declines in single countries were even greater than the global total, averaging one-quarter at respective peak confinement. Significant air quality improvements were also observed, especially in urban areas, attributable to a reduction in car use, factory production and construction activities (Wang Reference Wang, Yuan, Wang, Liu, Zhi and Cao2020b).

Despite large reductions during lockdowns, global carbon emissions have bounced back and are expected to decline by ‘only’ 7% in 2020 as a whole (Friedlingstein et al., Reference Friedlingstein, O'Sullivan, Jones, Andrew, Hauck, Olsen, Peters, Peters, Pongratz, Sitch, Le Quéré, Canadell, Ciais, Jackson, Alin, Aragão, Arneth, Arora and Zaehle2020). Emissions from cars and other vehicles have returned and are close to 2019 levels as economies are opening up, while emissions from air travel are still down by almost half. To make 2020 a turning point in global emissions, the 7% emission reductions expected for 2020 will need to be repeated year on year to reach net zero by mid-century (Hepburn et al., Reference Hepburn, O'Callaghan, Stern, Stiglitz and Zenghelis2020). Climate change response strategies with accelerated systemic changes in energy sources, technology, personal choices and additional policies (Barbier, Reference Barbier2020) are essential to stay on a low-carbon path.

Some major economies like the United States, Japan and Germany are implementing recovery packages amounting to nearly 15% of their GDP (Sovacool et al., Reference Sovacool, Furszyfer Del Rio and Griffiths2020a). The size of these packages means that they can lock the world into more or less green trajectories. The global investment requirement for a Paris-compatible pathway has been estimated to be 1.4 trillion USD per year in the period 2020–2024, a modest sum compared to the global stimulus funds (Andrijevic et al., Reference Andrijevic, Schleussner, Gidden, McCollum and Rogelj2020) amounting to more than 12 trillion USD. Investments in areas like clean physical infrastructure, building efficiency retrofits, education and training, natural capital and clean R&D can achieve both economic revitalization and climate goals simultaneously (Engström et al., Reference Engström, Gars, Jaakkola, Lindahl, Spiro and van Benthem2020; Gawel & Lehmann, Reference Gawel and Lehmann2020; Hepburn et al., Reference Hepburn, O'Callaghan, Stern, Stiglitz and Zenghelis2020; Malliet et al., Reference Malliet, Reynès, Landa, Hamdi-Cherif and Saussay2020). However, governments are not taking the opportunity to decarbonize about 3.7 trillion USD of stimulus funds being allocated to environmentally relevant sectors suitable for such green investments (Vivid Economics, 2020). Instead, G20 governments are committing 233 billion USD to fossil fuel-based (‘brown’) activities, compared to only 146 billion USD for green activities, as of November 2020 (SEI et al., 2020). This will lock in brown activities for years or even decades (Barbier, Reference Barbier2020; Hepburn et al., Reference Hepburn, O'Callaghan, Stern, Stiglitz and Zenghelis2020) and also reinforce the power structures favouring fossil fuel companies, including their ability to hinder climate policy (Kuzemko et al., Reference Kuzemko, Bradshaw, Bridge, Goldthau, Jewell, Overland, Scholten, Van de Graaf and Westphal2020; Mildenberger, Reference Mildenberger2020).

Although the GHG emission reductions caused by mobility restrictions were mostly temporary, governmental economic recovery efforts invested in low-carbon solutions could reduce global warming by 0.3°C by 2050 and put the world on track to meet the Paris Agreement goals (Forster et al., Reference Forster, Forster, Evans, Gidden, Jones, Keller, Lamboll, Le Quéré, Rogelj, Rosen, Schleussner, Richardson, Smith and Turnock2020). Unfortunately, based on the stimulus plans announced at time of as of this writing, most governments are still on crisis mode and so far appear to be missing this unique and critically important opportunity for green investments (Climate Action Tracker, 2020). The period following the containment of the pandemic, when additional recovery packages will be designed and released, will be crucial for the global climate.

3.7. The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrates the need for a new social compact for a just and climate-friendly world

The world has a unique opportunity to reshape the future in new directions. COVID-19, coupled with divided and divisive national responses, abruptly exposed the weaknesses of international cooperation in an era of climate crisis (Oldekop et al., Reference Oldekop, Horner, Hulme, Adhikari, Agarwal, Alford, Bakewell, Banks, Barrientos, Bastia, Bebbington, Das, Dimova, Duncombe, Enns, Fielding, Foster, Foster, Frederiksen and Zhang2020). COVID-19 has laid bare governance deficiencies in many countries and led to a disruptive new normal – the tackling of which requires transformative strategies and collaborations. COVID-19 and climate change are transboundary risks that affect all regions indiscriminately. No government, community or company can unilaterally address the systemic risks posed by COVID-19 or climate change to human well-being and economic and environmental security. Finding new ways to act together is crucial, and this requires the strengthening of capacity and inclusive forms of governance.

Systemic risks will continue to grow (Renn et al., Reference Renn, Lucas, Haas and Jaeger2019). Throughout 2020, climate disasters and actions to address COVID-19 have together imposed difficult economic and social hardships around the world, especially on marginalized communities, in many cases increasing inequality (Howarth et al., Reference Howarth, Bryant, Corner, Fankhauser, Gouldson, Whitmarsh and Willis2020). Yet, at the same time, responses to COVID-19, coupled with activism by social movements surrounding climate change, opens up new possibilities for transformation and underlines the need to develop a new global social compact for a more just and sustainable future (Dixson-Decleve et al., Reference Dixson-Declève, Schellnhuber and Raworth2020). People everywhere are increasingly aware of their vulnerabilities to emergent transnational risks and the threats they pose to global systems and supply chains for energy, food, water, transport and material goods (Laborde et al., Reference Laborde, Martin, Swinnen and Vos2020). Short-term political expediency is being challenged as communities demand effective, long-term and just solutions to global risks, particularly for the most vulnerable (Leach et al., Reference Leach, Reyers, Bai, Brondizio, Cook, Díaz, Espindola, Scobie, Stafford-Smith and Subramanian2018).

In 2020, the climate and pandemic crises catalysed the emergence of an informal, yet increasingly powerful global commitment to change:

(1) Youth, labour and indigenous climate movements redoubled their commitments to creating and sharing knowledge and pressuring governments and the private sector to act decisively, even in the face of significant hurdles (Hayward, Reference Hayward2020; Whyte, Reference Whyte2020). In July, the United Nations created the Youth Advisory Group on Climate Change.

(2) Public health researchers, the private sector and health officials urgently collaborated to develop effective responses to COVID-19 (Rourke et al., Reference Rourke, Eccleston-Turner, Phelan and Gostin2020), and the climate science community continued to advocate for action to address climate change and other systemic risks.

(3) Transnational networks of businesses, cities, regions and countries collaborated to fight COVID-19 and to set targets and develop strategies for achieving carbon-neutral or even carbon-negative economies by mid-century (Bai et al., Reference Bai, Nagendra, Shi and Liu2020). In October, the International Energy Agency (IEA) acknowledged that net-zero carbon by 2050 was the new standard for a clean energy transition and laid out a roadmap for the world to get there (IEA, 2020a).

Year 2020 witnessed a public willing to tackle systemic risks by transforming the intertwined social, economic and technological systems (Sovacool et al., Reference Sovacool, Hess, Amir, Geels, Hirsh, Medina, Miller, Palavicino, Phadke, Ryghaug, Schot, Silvast, Stephens, Stirling, Turnheim, van der Vleuten, van Lente and Yearley2020b) that have created overlapping crises of sustainability, health, equality and democracy (Miller, Reference Miller, Hoff, Gausset and Lex2019). Generating shifts in human values and new ways of thinking and acting are often harder to achieve than technical solutions. Yet, as public responses to COVID-19 have demonstrated, when motivated, people can and do change. New narratives and forms of imagination are emerging to guide transformative change and to facilitate a transition towards new, more sustainable and equitable models for the economy, more socially and environmentally responsible technological innovation, and more just systems of governance (Eschrich & Miller, Reference Eschrich and Miller2019; Iwaniec et al., Reference Iwaniec, Cook, Davidson, Berbés-Blázquez, Georgescu, Krayenhoff, Middel, Sampson and Grimm2020).

Translating this emergent global compact into stronger forms of international collaboration for the planet is the key to effective long-term responses to COVID-19 and climate change. Systemic risks will require innovative, adaptive, reflexive, transparent, participatory and accountable approaches to governance (Brown & Scobie, Reference Brown, Scobie, Betsill, Benney and Gerlak2020; Chou et al., Reference Cianconi, Betrò and Janiri2020). Rapid, networked, transformative responses that foster greater trust and more just relationships between diverse actors will be indispensable to creating a thriving and equitable global future for all (Scobie et al., Reference Scobie, Benney, Brown, Widerberg, Betsill, Benney and Gerlak2020).

3.8. Economic stimulus focused primarily on growth would jeopardize the Paris Agreement

An increasing number of studies provide solid evidence that there are substantial economic benefits of climate action in the short as well as long term. Climate mitigation has substantial co-benefits, here and now, in terms of local economic, environmental and health benefits (Karlsson et al., Reference Karlsson, Alfredsson and Westling2020; Rauner et al., Reference Rauner, Bauer, Dirnaichner, Van Dingenen, Mutel and Luderer2020). Recent research insights show that economically ‘optimal’ abatement could very well be in line with the UN climate targets of limiting global warming to well below 2°C and to actively pursue a 1.5°C limit (Burke et al., Reference Burke, Davis and Diffenbaugh2018a; Glanemann et al., Reference Glanemann, Willner and Levermann2020; Hänsel et al., Reference Hänsel, Drupp, Johansson, Nesje, Azar, Freeman, Groom and Sterner2020). As the remaining carbon budget is limited it is essential to use it on investments that lead to high net CO2 savings, that is, have a high return on investment in terms of CO2-emission reductions (Alfredsson & Malmaeus, Reference Alfredsson and Malmaeus2019).

An important driver for the changing cost landscape is the significant drop in costs being realized for renewable energy, battery storage and electric mobility. The global average levellized cost of electricity has fallen by 82% for solar photovoltaics, and 29 and 40% for offshore and onshore wind power respectively, between 2010 and 2019 (IRENA, 2020). Of all the newly commissioned utility-scale renewable power generation projects, 56% (by capacity) had a levellized cost lower than the cheapest new source of fossil fuel-fired power (IRENA, 2020). Batteries for electric vehicles in the United States have dropped in average price from more than 1100 USD/kWh in 2010 to 156 USD/kWh in 2019 (IEA, 2020b).

There is a risk, however, that gains from growing clean energy sources are offset by rapid growth of economic activity that increase the overall demand for energy slowing down system-wide decarbonization. Dyrstad et al. (Reference Dyrstad, Skonhoft, Christensen and Ødegaard2019) have shown that this has happened in OECD countries since 1980. A large body of literature finds that there has generally been – at a global level – a strong coupling between GDP growth, resource use and GHG emissions (Haberl et al., Reference Haberl, Wiedenhofer, Virág, Kalt, Plank, Brockway, Fishman, Hausknost, Krausmann, Leon-Gruchalski, Mayer, Pichler, Schaffartzik, Sousa, Streeck and Creutzig2020; Parrique et al., Reference Parrique, Barth, Briens, Kerschner, Kraus-Polk, Kuokkanen and Spangenberg2019; Vadén et al., Reference Vadén, Lähde, Majave, Järvensivu, Toivanen, Hakala and Eronen2020). In high-income countries there is, in terms of GHG emissions and if measured from a production perspective, evidence of a small absolute decoupling. Several countries have shown that it is possible to combine (low) economic growth with decreasing CO2 emissions, also for consumption-based emissions, when there are targeted policies (Le Quéré et al., Reference Le Quéré, Korsbakken, Wilson, Tosun, Andrew, Andres, Canadell, Jordan, Peters and van Vuuren2019). Still, current policies are insufficient to reduce emissions globally at the rate needed to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement (Roelfsema et al., Reference Roelfsema, van Soest, Harmsen, van Vuuren, Bertram, den Elzen, Höhne, Iacobuta, Krey, Kriegler, Luderer, Riahi, Ueckerdt, Després, Drouet, Emmerling, Frank, Fricko, Gidden and Vishwanathan2020).

The decarbonization rate and mitigation costs not only depend on technology development, but also on the rate and type of economic development. In order to stay below 2°C, modelling scenarios with high growth often require CO2 removal (CDR) at quantities that threaten several sustainability goals. Van Vuuren et al. (Reference Van Vuuren, Stehfest, Gernaat, van den Berg, Bijl, Sytze de Boer, Daioglou, Doelman, Edelenbosch, Harmsen, Hof and van Sluisveld2018) show that in a scenario with moderate growth, the needs for CDR can be greatly reduced when combining a technology transition with substantial behavioural changes.

Weighing in the critical time factor, recent scientific evidence shows that if the economic recovery after COVID-19 has a primary focus on economic growth, with sustainability and climate mitigation as a secondary goal, it could jeopardize our last chance of achieving the Paris Agreement and safeguarding people's health, well-being and a prosperous economic development.

This insight is further elaborated on in the Supplementary material.

3.9. Electrification increasingly pivotal for just sustainability transitions and urban areas are at the forefront

Urban electrification has accelerated in recent years (World Economic Forum, 2020). However, although the decarbonization impacts of electrification are well documented in industrial and transport sectors (Alarfaj et al., Reference Alarfaj, Griffin and Samaras2020; Arabzadeh et al. (Reference Arabzadeh, Mikkola, Jasiūnas and Lund2020); Lah et al., Reference Yang, Roderick, Zhang, McVicar and Donohue2020; Madeddu et al., Reference Madeddu, Ueckerdt, Pehl, Peterseim, Lord, Kumar, Krüger and Luderer2020; Mai et al., Reference Mai, Jadun, Logan, McMillan, Muratori, Steinberg, Vimmerstedt, Jones, Haley and Nelson2020), comprehensive analyses of the role that urban electrification can play are lacking (Fuso Nerini et al., Reference Fuso Nerini, Slob, Ericsdotter Engström and Trutnevyte2019). The sustainable energy transition relies on a concurrent global urban transition (IRENA, 2019; IPCC et al., Reference Masson-Delmotte, Zhai, Pörtner, Roberts, Skea, Shukla, Pirani, Moufouma-Okia, Péan, Pidcock, Connors, Matthews, Chen, Zhou, Gomis, Lonnoy, Maycock, Tignor and Waterfield2018). Urban electrification offers opportunities to examine the challenges and harness the opportunities of urbanization and decarbonization in tandem (Romero-Lankao et al., Reference Romero-Lankao, Wilson, Sperling, Miller, Zimny-Schmitt, Bettencourt, Wood, Young, Muratori, Arent, O'Malley, Sovacool, Brown, Southworth, Bazilian, Gearhart, Beukes and Zund2019; Allam et al., Reference Allam, Jones, Thondoo, Allam, Jones and Thondoo2020); it opens up new areas of discussion for bridging urban and energy planning, which require interdisciplinary dialogues. Cities will need to develop new solutions, including fundamental structural and systemic changes, to cope with expected urbanization trends (Salvucci & Tattini, Reference Salvucci, Tattini, Holst Jørgensen, Krogh Andersen and Anker Nielsen2019) and other emerging technological innovations, like e-commerce and e-ride hailing.

The current wave of electrification is mainly driven by urban buildings and on-road transportation, especially battery electric vehicles, heat pumps and cookstoves (Romero-Lankao et al., Reference Romero-Lankao, Wilson, Sperling, Miller, Zimny-Schmitt, Bettencourt, Wood, Young, Muratori, Arent, O'Malley, Sovacool, Brown, Southworth, Bazilian, Gearhart, Beukes and Zund2019). Electric utilities and investors see these changes as new sources of growth, as can be seen from the global trends in investment in electricity networks. Rates of decline in carbon intensity are forecast to be faster in cities and with municipally owned utilities, due to their renewable targets, unique regulatory structures and prominent role in regional, state and national economies (REN21, 2019). Electrification via micro-grids can support the development of a small- and medium-sized enterprise-based industry (Ganguly et al., Reference Ganguly, Jain, Sharma and Shekhar2020), that shares economic benefits throughout communities (Westman, Moores & Burch, Reference Westman, Moores and Burch2021), and is linked with improvements in per capita income (Akin et al., Reference Aklin, Harish and Urpelainen2018). However, there is hardly any effort to examine those possibilities in urban contexts.

The expectation is that urban electrification can help leapfrog societies towards low-carbon sustainable energy systems and facilitate broad-based, just changes in the urban environment, thereby aligning adaptation and mitigation with the SDGs (IPCC, Reference Masson-Delmotte, Zhai, Pörtner, Roberts, Skea, Shukla, Pirani, Moufouma-Okia, Péan, Pidcock, Connors, Matthews, Chen, Zhou, Gomis, Lonnoy, Maycock, Tignor and Waterfield2018). Reductions in local air pollution and improvements to health and quality of life are some tangible co-benefits of urban electrification (REN21, 2019). Cities, including government, community and private actors, are at the forefront of innovation and adoption of technologies and thereby can be hubs of accelerated and equitable energy transitions (Bai et al, Reference Bai, Dawson, Ürge-Vorsatz, Delgado, Salisu Barau, Dhakal, Dodman, Leonardsen, Masson-Delmotte, Roberts and Schultz2018; de Chalendar, Reference de Chalendar, Glynn and Benson2019; Kern, Reference Kern2019; Romero-Lankao, Reference Romero-Lankao, Bulkeley, Pelling, Burch, Gordon, Gupta, Johnson, Kurian, Lecavalier, Simon, Tozer, Ziervogel and Munshi2018; Ryan, Reference Ryan2015). Cities are also places of informal settlements, environmental inequalities and energy poverty; and adaptation may increase energy demand (Gielen et al., Reference Gielen, Boshell, Saygin, Bazilian, Wagner and Gorini2019).

Urban electrification opens up opportunities to provide access to clean and affordable energy from renewable sources (e.g. Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Kennedy, Facchini and Mele2018) to over a billion people in the world who lack access to electricity, many of whom live in rapidly urbanizing areas or urbanized areas where access to electricity is highly uneven (de Collaço et al., Reference de Collaço, Dias, Simoes, Pukšec, Seixas and Bermann2019).

Urban electrification can help democratize electricity provision (Burke & Stephens, Reference Burke and Stephens2018). Decentralized energy systems, for example, can facilitate a transition away from exclusively centralized high-carbon electricity systems (Adil & Ko, Reference Adil and Ko2016), returning control to citizens over energy systems. Notable risks stem from significant inequalities of access to decision-making on investments and technologies; unmitigated, these factors could deepen the divide between those who benefit and can afford low-carbon systems and those who do not, or who bear the negative impacts (Korkovelos et al., Reference Korkovelos, Zerriffi, Howells, Bazilian, Rogner and Fuso Nerini2020). This electrification divide is a question that has not yet received sufficient attention in the academic literature.

Many actions can help realize the potential of urban electrification. Communities, local officials and utilities are introducing decentralized power systems such as distributed energy generation, micro-grids and smart grids (Adil & Ko, Reference Adil and Ko2016; Pullins, Reference Pullins2019). City officials are promoting the use of renewables in their government-owned facilities and also integrating them into their building codes (Schmid et al., Reference Schmid, Meister, Klagge and Seidl2020). Infrastructure is also being deployed to support end-use electrification, like electric vehicle charging solutions (IEA, 2020b).

It is, increasingly, grassroot movements that drive actions at the city level, involving diverse stakeholders. Youth climate activists, community actors and transnational networks are engaging in a variety of actions from working on urban planning, green transport and grid integration, to challenging existing power relationships around current energy regimes as well as the actors and political authorities who maintain them (Szulecki, Reference Szulecki2018). Urban electrification benefits, including reduction of GHG emissions, will be realized only if the demands of the built environment, institutional constraints and the carbon intensity of energy sources are addressed (Castan Broto, 2019; Romero-Lankao et al., Reference Romero-Lankao, Wilson, Sperling, Miller, Zimny-Schmitt, Bettencourt, Wood, Young, Muratori, Arent, O'Malley, Sovacool, Brown, Southworth, Bazilian, Gearhart, Beukes and Zund2019).

This insight is further elaborated on in the Supplementary material.

3.10. Rights-based litigation as an essential tool in climate action

Litigation is an essential tool to urge action to prevent dangerous climate change and support the goals of the Paris Agreement (Gerrard, Reference Gerrard2019; Setzer & Byrnes, Reference Setzer and Byrnes2019; International Bar Association, 2020; Mitkidis & Valkanou, Reference Mitkidis and Valkanou2020; Wegener, Reference Wegener2020). Most climate cases are public interest litigation against a government (e.g. Urgenda Foundation v. State of the Netherlands, 2020) although claims are also brought against private actors such as oil companies (e.g. Milieudefensie et al., v. Royal Dutch Shell plc., filed in 2019), and can be initiated before domestic courts and international courts, tribunals or human rights treaty bodies or non-compliance mechanisms (Spijkers, Reference Spijkers2020). Developing climate policy is typically the domain of the legislative branch of the State, but given the urgency to act and the absence of adequate climate action or enforcement, the courts come in as ‘lawmakers’ (Spijkers & Oosterhuis, Reference Spijkers, Oosterhuis and Muinzer2020; Voigt, Reference Voigt2019). This challenges conventional interpretations of the balance of power and features a critical interplay between scientific evidence and adjudication.

Climate cases have been based primarily on alleged human rights violations, around which litigation in developing countries, particularly in Latin America, is growing in scale and extent (Peel & Lin, Reference Peel and Lin2019). Such rights-based litigation appears to be a suitable and effective channel to clarify the content and scope of existing human rights, such as the right to life and the right to a private life, in light of climate change impacts (Rodríguez-Garavito, Reference Rodríguez-Garavito2020). The human rights prism has also led to a more focused debate on the obligation of conduct that states have in order to avoid dangerous climate change. This in particular details the definition of due diligence and the requirement of states to reflect on their highest possible ambition in their national climate plans, policies and laws. Moreover, climate litigation plays an important role in defining the content of a human right to a clean and healthy environment, and how this relates to the duty to inform, the precautionary principle and other substantive and procedural principles of international environmental law (Peel & Osofsky, Reference Peel and Osofsky2018).

Responsibility for extraterritorial emissions or harm is another critical issue addressed by climate litigation. One contentious issue in this context is whether states are responsible and should account for ‘imported emissions’ (which are produced elsewhere and cause emissions during those processes but are consumed ‘at home’) or ‘exported emissions’ (the result of exported oil and gas products that are refined and burned abroad). Extraterritoriality also applies to human rights violations due to climate impacts, where the cause of such impacts may have been in states other than those whose people are the victims of such harm.

Climate litigation clarifies the issue of international legal standing and representation of the rights and interests of future generations in a healthy environment. Standing is closely linked to establishing victimhood, which may involve future harm or harm to future generations. In some instances, children have initiated cases or similar proceedings as representatives of future generations. In September 2019, 16 children – representing 12 nationalities – filed complaints against five countries before the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child, and a group of Portuguese youth lodged an application in September 2020 at the European Court of Human Rights against 33 states to provoke legally binding climate action.

Furthermore, there has been an increase in climate-related cases yielding legal rights of nature. For example, Asociación Civil por la Justicia Ambiental v. Province of Entre Ríos, et al., filed 7 July 2020 in Argentina; and Demanda Generaciones Futuras v. Minambiente, (Republica de Colombia, 2018), which found the Amazon to have standing and be subject to protection. The number of different actors who can represent climate-related cases has widened, such as an NGO (McGrath, Reference McGrath2019), ombudsperson, trustee, institution, governmental agency or a select group of individuals. Also, courts, compliance procedures and human rights treaty bodies are starting to be asked to recognize the standing and rights of those who leave their country because it no longer sustains their life – known as climate migrants, like the case of Ioane Teitiota v. New Zealand (24 October 2019).

During recent decades, states have considered International Courts and Tribunals (ICT) to be an appropriate forum for the settlement of their international environmental legal disputes. ICTs are increasingly recognized as a potentially powerful venue for adjudication on climate and the court's jurisdiction to advise. This is due also to the demonstrated influence and cross-fertilization among judges, courts and tribunals at domestic, regional and international levels (Saiger, Reference Saiger2019; Wegener, Reference Wegener2020). Recent decisions of ICT have highlighted the challenges of resolving environmental disputes, such as the assessment of the evidence and the complexity of reparation for the loss of environmental goods and services, including gas regulation and carbon sequestration.

In summary, important developments are seen in climate litigation concerning the expansion of who and what has legal standing in courts, who may represent interests such as that of future generations, how to address harm across national boundaries, the role of courts in mandating climate action and cross-fertilization between courts and tribunals across levels and scales.

This insight is further elaborated on in the Supplementary material.

4. Conclusions

Year 2020 will enter history as the year in which the COVID-19 pandemic ravaged our world and reshaped our lives. Global responses to the pandemic provide a unique opportunity for the crucial large-scale sustainable investments needed to reach the Paris Agreement goals; these are investments that in turn are needed for healthy, sustainable lifestyles and a prosperous economic development. Although our horizon scan identifies a continued amplification in key environmental impacts (e.g. emissions and permafrost thaw), it also points to opportunities that arise from new views on climate change economics and governance, partially in response to the pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic not only reinforces the links between human health and climate change, it also provides a strong manifestation of how global crises can emerge in the hyper-connected world of the Anthropocene. Furthermore, it provides a unique opportunity for positive change by stimulating new social contracts and narratives but it's critical that economic stimulus measures reduce the risk of climate change rather than to drive short-term economic growth. Ultimately, the most fundamental 2020 insight may be that the world's nations and citizens can act together in the face of global threats and, although we cannot yet be said to be on the right climate trajectory, we can draw upon science and evidence to shape a safe, equitable and resilient future.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/sus.2021.2

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge support from Future Earth, The Earth League, World Climate Research Programme (WCRP), Arizona State University, Earth System Governance Project (ESG Project), Integrated Land Ecosystem-Atmosphere Processes Study (iLEAPS), Global Carbon Project (GCP) and Future Earth's Knowledge-Action Networks for (a) Health, (b) Systems of Sustainable Consumption and Production and (c) Urban. We further acknowledge support from Clara Burgard at Helmholtz-Zentrum Geesthacht and The Earth League, Roy Yi Ling Ngerng, National Taiwan University and Maria Martin at University of Potsdam, Institute for Climate Impact Research.

Author contributions

HAC, EF, TH, SL, HN, JohR, PR-L, DBS, LS and PS constituted the Editorial Board, conceiving and designing the study and providing editorial oversight. EP coordinated and provided editorial oversight. CME, SRH, RAL, CP, EP and GBS coordinated writing. EA, MB, KJB, VCB, KTC, KE, CME, PF, AG-F, MG, ARH, KH, BMH, SRH, GH, TI, RBJ, TFK, RAL, MiM, MaM, RIM, CM, CAM, NN, EASO, CP, JoP, JuP, PR-L, JoyR, AAS, ES, MS, SCS, GBS, JaS, JHS, OS, PHCT, MRT, AMU, DPvV, CV, CW and MDZ performed investigations and writing.

Financial support

VCB was supported by European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme, Grant Agreement No. 804051- LOACT – ERC-2018-Stg. PF was supported by the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under 4C (Grant Agreement No. 821003). AGF was supported by ANID/FONDAP/15130015. SRH was supported by the European Space Agency (ESA). GH was supported by The European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation project Nunataryuk (773421). TH acknowledges support from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 821471 (ENGAGE). TI acknowledges support by European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 821003 (4C) and European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 641816 (CRESCENDO). TFK acknowledges support by the Reducing Uncertainties in Biogeochemical Interactions through Synthesis and Computation Scientific Focus Area (RUBISCO SFA), which is sponsored by the Regional and Global Model Analysis (RGMA) Program in the Climate and Environmental Sciences Division (CESD) of the Office of Biological and Environmental Research (BER) in the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. NN acknowledges support from Global Affairs Canada. PR-L acknowledges support by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), operated by Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC, for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) under Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308. JoP was supported by the European Research Council Synergy grant (ERC-SyG-2013-610028 IMBALANCE-P), the Spanish Government grant PID2019-110521GB-I00 and the Catalan government grant SGR2017-1005. AAS was supported by the Met Office Hadley Centre Climate Programme funded by BEIS and Defra. ES acknowledges support from NSF PLR Arctic System Science Research Networking Activities (RNA) Permafrost Carbon Network: Synthesizing Flux Observations for Benchmarking Model Projections of Permafrost Carbon Exchange, Grant no. 1931333. (2019–2023). SCS's work was supported by the Australian Research Council grant FL150100035. GBS would like to acknowledge the International Research Fellow programme of Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. PHCT's work was supported by a share of a grant from The São Paulo Research Foundation – FAPESP (grant number 2018/06685-9). EF acknowledges support from the Nordic Africa Institute. AMU acknowledges support from the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes (CE170100023). The effort of MDZ was performed under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract DE-AC52-07NA27344 and was supported by the Regional and Global Model Analysis Program of the Office of Science at the DOE.

Conflict of interest

Johan Rockström is the current Editor-in-Chief of Global Sustainability journal. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.