The economic crisis had its most dire effects in Southern Europe. Social protest proliferated, culminating in an ‘electoral’ and later ‘government epidemic’ (Bosco and Verney Reference Bosco and Verney2016). Financial and political crises converged with a twofold effect, both domestic and European. ‘Challenger parties’ emerged, embodying opposition to austerity policies, demanding renewal of ‘antiquated’ political systems and raising concerns about the fate of the nation state in the context of the balance of power between creditor and debtor nations in the EU (Hutter et al. Reference Hutter, Kriesi and Vidal2018).

The radical left has proved to be a challenging political force, one that has moved from being a ‘pariah’ to being a ‘participant’ (Bale and Dunphy Reference Bale, Dunphy, De Waele and Seiler2012). For the first time it seemed to be going beyond its post-1989 ‘decline and/or mutation’ dilemma (Lazar Reference Lazar1992; March and Mudde Reference March and Mudde2005). It acquired electoral visibility and became a threat to the mainstream centre left, whose decline had started even before the advent of the crisis. Social democracy found itself trapped in a Faustian pact that could be traced back to its previous strategic orientations and made it impossible to impose a Euro-Keynesian response. Now it was social democracy that was facing a similar dilemma: ‘renovation or resignation’, ‘restoration or renewal’ (Arndt and van Kersbergen Reference Arndt and van Kersbergen2015; Escalona and Vieira Reference Escalona and Vieira2014).

If during the Third Way period its moderate politics enabled social democracy to win over centrist middle-class voters, today it looks much less capable of representing the traditional and new middle class (Arndt Reference Arndt2013). On the other hand, the association of radical left with the social radicalism generated by the crisis made it not only politically significant but also interesting from a research standpoint: academic literature on the radical left is flourishing, notwithstanding its predominant association with populism (Kriesi and Pappas Reference Kriesi and Pappas2015; March Reference March2007; Ramiro and Gomez Reference Ramiro and Gomez2017). Populist or not, the radical left's rhetoric and strategy have enabled it to make its claim as an actor with government/coalition potential. The aim of this article, through a straightforward research question, is to revisit the two party families in their interaction: has the crisis as experienced in different countries modified the dynamics of this enduring relationship of competition and symbiosis? In what ways has the pattern of radical left being a pariah and social democracy an incontestable force for government – a disposition quasi-frozen since the 1990s – now been disrupted? And what are the factors of convergence/divergence between the two?

Analytical framework

The extensive bibliography on social democracy touches on its organic ties with the unions and the political representation of the working class. At the epicentre of social democratic compromise was the taming of material insecurity and inequality, without great sacrifices on the part of macroeconomic stability (Moschonas Reference Moschonas2002). Recent research has focused on its historical path (Berman Reference Berman2006); the Third Way as moment of adaptation to globalization (Cramme and Diamond Reference Cramme and Diamond2012); the European dimension (Dimitrakopoulos Reference Dimitrakopoulos2012); the social democratic political economy from Keynesian ‘orthodoxy’ to ‘social-liberal’ adaptation (Andersson Reference Andersson2009).

The radical left is a post-communist party family which promotes root-and-branch change without renouncing liberal democracy. Its traditional anti-capitalism has changed into opposition to ‘neoliberal globalization’ (March Reference March2011). The literature gradually began to approach the trajectory of this family ‘from marginality to mainstream’ (Bale and Dunphy Reference Bale, Dunphy, De Waele and Seiler2012; March and Keith Reference March and Keith2016). In this context, what has been the subject of particular study is the attitude of the radical left towards the EU (Dunphy Reference Dunphy2004; Charalambous Reference Charalambous2011), its transnational networking (Dunphy and March Reference Dunphy and March2013), participation in coalition governments (Bale and Dunphy Reference Bale and Dunphy2011), electoral performance (March and Rommerskirchen Reference March and Rommerskirchen2015), policies and materialist/post-materialist agenda (Fagerholm Reference Fagerholm2017).

Despite the fact that the literature on social democracy is extensive and the approaches on the radical left are proliferating, there is an absence of studies focused specifically on their interaction, which since 2008 has been significant. The cases and causes of increased political power of the communist left versus social democracy have been studied from a macro-historical perspective (Bartolini Reference Bartolini2000), as have the convergences and deviations of the two ‘enemy brothers’ during the critical juncture of 1960–70 (Rand Smith Reference Rand Smith2015).

Our research takes place in precisely this gap: we propose to examine the two party families not on an individual basis but from a relational perspective in a number of case studies. Two of them concern countries on the European periphery that have been subjected to fiscal stabilization programmes (a sovereign debt crisis that soon turned into a sociopolitical crisis in Greece and a debt crisis followed by intense austerity, albeit with lesser sociopolitical repercussions, in Portugal). Also examined are the economic crisis in Spain, which was treated to an informal reorganization plan, and crises-in-the-crisis (corruption/Catalonia), not to mention the crisis in France, which saw its hegemonic role in Europe contracting and has experienced an internal national identity crisis, giving rise to the radical extreme right in a development whose consequences have been more severe than the effects of a certain economic stagnation. The frame of reference is the political and electoral cycle of 2015–17: SYRIZA's rise to power in Greece, ‘government epidemic’ in Portugal and Spain, and the critical French presidential election.

It is arguable that the crisis is the critical juncture which poses external challenges to the parties in question, forcing them to develop response strategies which eventually shape future path dependencies – even if this period of significant change occurs in ways which differ from country to country since it unfolds within the context of distinct party-system dynamics. The crisis as a critical juncture consists in a combination of antecedent conditions, cleavages that emerge and trigger the change, and different legacies that are produced (Collier and Collier Reference Collier and Collier1991). The aim of this article is thus to investigate whether the different responses of these parties to the varieties of crisis in each country and their strategic reorientations have created the conditions for convergence or moved the two party families further apart. Simple empirical observation indicates that convergence was indeed attempted or achieved, or favourable conditions to that end created: governmental cooperation in Portugal; unsuccessful and then successful attempts at such cooperation in Spain; an on-again off-again dialogue between the two in Greece and France.

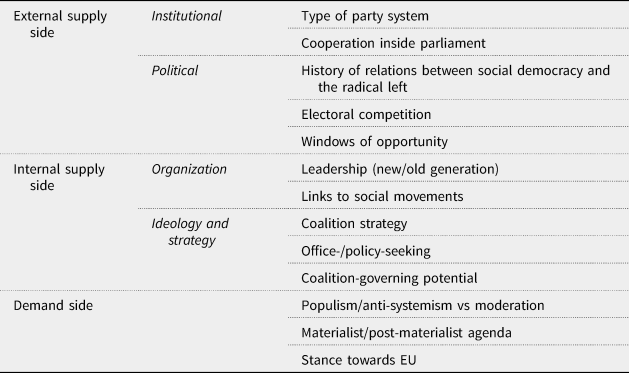

For the purpose of approaching the research question, we will thus examine the radical left and social democratic parties of these countries in their interaction. The empirical data consist in a corpus of party documents, speeches and public interventions of party leaders as well as secondary literature, considered in the light of certain critical interpretative factors. We will regard these parties as rational collective actors who are de facto ‘neighbours on the scale’ (Luebbert Reference Luebbert1983), thus examining their office-, policy- and vote-seeking tactics (Müller and Strøm Reference Müller and Strøm1999) as well as their attempts to gain coalition-blackmail or governing potential. But parties do not pursue their action in abstracto; rather, they operate in certain institutional and historical conditions which determine the possibilities and limits of their action. Party strategies are thus framed by four sets of factors: (1) institutional factors; (2) party competition and structures of political opportunity; (3) internal party dynamics; and (4) national–global economic and political conjuncture and external shocks (Olsen et al. Reference Olsen, Hough and Koss2010). Following the demand-and-supply scheme, institutional factors and party competition belong to the external supply side, whereas internal party dynamics belong to the internal supply side. Situational factors belong to the demand side and at the same time generate political and ideological responses to specific problems that are therefore also linked to the internal supply side (March and Rommerskirchen Reference March and Rommerskirchen2015; Mudde Reference Mudde2007) (see Table 1). In what follows we will examine how these factors affect the strategic paths pursued by social democratic and radical left parties in the four countries, and which of the above conditions are expected to lead to more cooperation or competition.

Table 1. Supply-/Demand-Side Factors of Convergence or Divergence

From the external supply side, in their diverging historical paths, social democratic parties evolved into large office-seeking catch-all institutions, weakening their ideological identity for the sake of maximizing their electoral performance, whereas communist parties remained smaller, policy-seeking players, with a strong ideological slant. The question is whether this pattern and the dynamics of their electoral competition, especially since the 1990s, was disrupted by the crisis and whether such a development could bring the two closer together than in the recent past. To this we should add institutional factors such as the destabilization of party systems where social democracy is (was) one of the two pillars of bipartisanship, or the patterns of cooperation inside the parliament. Last but not least, when after 2008 social democrats in governmental positions implemented austerity policies, the radical left benefited from structures of political opportunity (Tarrow Reference Tarrow1994) such as the Aganaktismenoi and Indignados (meaning ‘indignants’ in both cases) movements in Greece and Spain. In what ways do these factors bring significant change in the political competition or collaboration of the two families?

Concerning the internal supply-side factors, one classic social democratic strategy was to form governments in collaboration with parties to their left only when in a strong position electorally. In circumstances of electoral downturn the preference was for collaboration either with centre-right parties (‘grand coalitions’) or other smaller parties (Hough and Verge Reference Hough and Verge2009). However, during the crisis in Spain the coalition strategy with the centre right was called into question, and in Portugal a coalition with the left was formed even though social democrats were not in a position of strength. On the other hand, the radical left overcame its 2000s fixation with social protest and dealt with the issues of governance, even at the price of its ideology (in Greece, Spain and Portugal). How are the coalition strategies of the two families, before and during the crisis, expected to affect their competition or approximation? Is the social democrats’ effort to maintain their governing potential and the left's passage from social movements to office-seeking tactics a factor for distancing or of cooperation? And how is the whole picture affected by the rise of a new generation in the leadership of the parties under examination?

Finally, from the demand side, the convergence/divergence ratio depends on a series of distinctive features that are directly related to the challenging external shock of the crisis. The most critical of them, which we consider to be of particular interpretative value, are the following:

Firstly, materialist/post-materialist orientations (Inglehart Reference Inglehart1977). Recent literature detects a ‘return’ of traditional materialist values, with which the radical left is more at ease. As the economic crisis erodes the conditions of material prosperty from which social democracy had benefited, enabling it to shift its focus to post-materialist questions, we may well wonder what the consequences of this might be for the relationship between the two party families.

A second parameter is the emergence of an anti-system populist style, mainly on the side of the radical left, which indirectly attacks social democracy by challenging its reformist, moderate and mainstream profile. The conflict between systemic and anti-system/populist characters also functions as a regulator of convergence/divergence.

Thirdly, a key indicator is their attitude towards European integration. This is their positioning between strong/weak European reformism and hard/soft Euroscepticism (Dunphy Reference Dunphy2004; Szczerbiak and Taggart Reference Szczerbiak and Taggart2008) as the ‘permissive consensus’ of the pre-Maastricht period is crystallizing into a ‘constraining dissensus’ (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2005), multiplying the varieties of criticism against the European project and shifting formerly fixed attitudes, which could be expected to lead to more cooperation rather than competition.

The current crisis offers a good opportunity to reassess the two neighbouring, albeit unequal, party families through their interaction, which is intensifying even as they develop different dynamics οf ascension and weakening, of transformation, mutation and adaptation. Our working hypothesis is that this critical juncture, with its specific demand-side dimensions along with its effects on the supply side, has led social democracy and radical left parties to respond strategically in ways far different from previous years. The comparative study of different national cases from this point of view may enlighten us as to the ongoing reconfiguration of the profile of the two party families, on the basis of the forementioned factors that bring them closer together or move them further apart.

Greece: polarized enemies, realist brothers?

The case of Greece is most striking: nowhere else has a party of the radical left formed a government; nowhere else has social democracy become so fragmented. SYRIZA is a left-wing coalition with Synaspismos as its main component, a party with a Eurocommunist tradition of political moderation, a Europeanism and new politics agenda. PASOK, on the other hand, used to be one of the two main pillars of the post-dictatorship bipartisanship: a hegemonic party that went through a radical-populist phase in the 1980s and moved to a ‘Third Way’ agenda in the 1990s. The relationship between the two in the post-dictatorship period was one of political proximity but also of suspicion due to their unequal magnitude; when Kostas Simitis, prime minister and leader of PASOK, invited Synaspismos to form a centre-left coalition at its Second Congress in 1996, the latter did not reciprocate for fear that it would eventually be absorbed by the larger party.

In the last election before the crisis (2009), PASOK formed a government with 43.9% of the vote, whereas SYRIZA remained a small opposition force. In the ‘electoral earthquake’ of 2012, PASOK collapsed to 13.2% in May and 12.3% in June, with SYRIZA emerging as the main opposition party with 16.8% and 26.9% respectively (Voulgaris and Nikolakopoulos Reference Voulgaris and Nikolakopoulos2014). PASOK was the party that handled the first tough adjustment programme. Although elected on a pre-crisis agenda of sustainable development, e-government and human rights (PASOK 2009), it found itself enforcing austerity policies very far from its socialist profile. SYRIZA took advantage of the opportunity which emerged in spring 2011 with the Aganaktismenoi movement and concluded at the end of 2011, when PASOK was forced to govern together with its perennial adversary, the conservative Nea Dimokratia (ND – New Democracy) – which led the established bipartisanship to crumble.

The rise of SYRIZA was attributed to its social-populist discourse as well as the successful combination of protest and manipulation of the political agenda (Katsambekis Reference Katsambekis2016; Stavrakakis Reference Stavrakakis2015; Tsakatika Reference Tsakatika2016). For the most part, however, SYRIZA forged a three-part approach which paved the way to power, unlike the ‘orthodox’ Kommounistiko Komma Elladas (KKE – Communist Party of Greece), which remained confined to a strictly class-oriented strategy (Lamprinou and Balampanidis Reference Lamprinou, Balampanidis, Voulgaris and Nikolakopoulos2014). First, SYRIZA aligned itself with an ambivalent public opinion combining a soft but increasingly intense Euroscepticism aimed at ‘overthrowing the neoliberal European edifice’ (Synaspismos 2011) with a denunciation of the Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece (also known as the ‘Memorandum’) as undermining national sovereignty (Tsipras Reference Tsipras2011). Second, it identified with every sort of social mobilization through a typically populist appeal to the ‘people’; and, third, it created a strong leader profile in the charismatic person of Alexis Tsipras.

It was just before the 2012 elections that the small left party turned from policy-seeking into office-seeking, requesting a vote for governance, not protest, as the government-oriented PASOK entered a downward spiral. From then on the relationship between the two underwent a reversal. SYRIZA aspired to being recognized as having a ‘legitimate’ right to govern, while the fragmented social democrats sought to maintain a coalition-blackmail potential, promoting their competence and European orientation.

SYRIZA sideswiped PASOK, accusing ‘traditional social democracy’ of fully assimilating neoliberal policies (SYRIZA 2013), while PASOK pressed it to participate in a government of national unity – as did the Democratic Left (DIMAR), SYRIZA's moderate wing that broke away in 2010. SYRIZA countered with a ‘left-wing government’ plan that would put an end to the Memorandum and denounced the ND-PASOK-DIMAR government under Antonis Samaras as a coalition of the ‘Memorandum forces’ that belong to the ‘old’ political system.

The two ally-antagonists in the reconstruction of the centre left, PASOK and DIMAR, bore the brunt of governmental discredit as the tripartite coalition's minor partners, with DIMAR eventually leaving the coalition when ND and Samaras decided to shut down public television in June 2013 without consulting their coalition partners. Now a new player was added to the centre-left game: civil society ‘Initiative 58’ attempted to bring together PASOK and DIMAR in a ‘progressive popular Europeanism’ that would face off both ‘the right and the neo-communist Left’ (Initiative 58 2013).

Soon, Initiative 58 was disbanded as a result of disagreements over the ballot for ‘Elia’, the new scheme that PASOK was promoting. Elia, headed by PASOK president and vice-president of the Samaras government V. Venizelos, was to be pitted against SYRIZA and its ‘populism and irrational anti-Europeanism’ (Elia 2014). When Initiative 58 disbanded, another new player appeared: Potami, headed by journalist S. Theodorakis, proposed a European reformism that would transcend left and right (Potami 2014). Like SYRIZA it claimed to be rising above the ‘old’ political system, but unlike SYRIZA it espoused positions that were more or less favourable to the adjustment programme.

The European elections of 2014 confirmed the split in the centre left (Elia 8%, Potami 6.6%, DIMAR 1.2%); the anticipated rise of SYRIZA to power forced the three parties to adjust their strategy. They put pressure on SYRIZA, focusing on two major issues: on the one hand, keeping the country in the eurozone (i.e. a ‘correction’ to SYRIZA's ambivalence towards the EU), and on the other, SYRIZA's lack of realism and competence to govern.

In January 2015, SYRIZA formed a government in collaboration with Independent Greeks (ANEL), a small anti-Memorandum party of the far right. SYRIZA represented a retrospective economic vote which rejected the adjustment programme, without any radical questioning of Greece's position in the EU (Tsirbas Reference Tsirbas2015). It also expressed an anti-Memorandum vote overlapping with rejection of the ‘old’ political system (Hutter et al. Reference Hutter, Kriesi and Vidal2018). In the September elections, after the referendum on whether Greece was to accept the bailout conditions in the country's government debt crisis proposed by the European Commission, IMF and ECB, and the painful compromise with the lenders, its anti-Memorandum aspect necessarily receded and its opposition to the ‘old’ party system emerged more predominantly. SYRIZA was able to express this equally well (Tsatsanis and Teperoglou Reference Tsatsanis and Teperoglou2016).

The same election was a watershed for PASOK (4.7%) and DIMAR (0.5%), which both moved towards a change of leadership and the formation of a common undertaking, the Democratic Coalition. In its founding manifesto it combined a pro-European orientation with a turn towards social issues, all the time keeping an equal distance from ND and SYRIZA (Dimokratiki Symparataxi 2016). Given that up until the September 2015 elections SYRIZA had chosen not to jeopardize the country's position in the eurozone, the Democratic Coalition downplayed the anti-SYRIZA attitude of the Venizelos era, but looked back at the strategic partnership with ND as having diluted its progressive positions and reasserted itself as a ‘neighbour on the scale’ with SYRIZA. In parliament, too, it voted for crucial government bills on TV licences, a one-off bonus to pensioners, and a same-sex cohabitation agreement.

Following the signing of the third Memorandum, SYRIZA developed a dual strategy: on the one hand it denounced social democracy; on the other it flirted with it (Tsipras Reference Tsipras2015), especially at the European level, having participated as an observer at the meetings of the European social democrats. By October 2016, the approach to ‘European Social Democracy and the Greens’ was made formal (Tsipras Reference Tsipras2016), despite the objections of the party's left wing (Initiative 53+ 2016). Meanwhile, the centre left took a further step in its unification venture (PASOK, DIMAR, Potami), the central dilemma being whether to form a strategic alliance with a potential ND government or make an approach to SYRIZA. The winner of the primaries for the leadership of the new unified party, PASOK president Fofi Gennimata, signalled a repositioning on the left–right axis, calling for ‘progress’ rather than ‘conservative restoration’ (Gennimata Reference Gennimata2017). But soon after the foreign ministers of Greece and former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia(FYROM) signed a deal with the potential to resolve a long-running dispute over the latter's name, PASOK aligned itself with ND in a nationalist rhetoric against the deal, hoping, by stimulating their patriotic reflexes, to repatriate its former voters who had moved to SYRIZA. This caused a split, with Potami abandoning the centre-left unification venture, and triggered a series of internal disputes in PASOK over the risks of identification with ND.

The case of Greece appears to be a European anomaly. The established policy- and office-seeking roles were reversed, with SYRIZA coming into power and PASOK, along with other smaller centre-left players, trying to maintain coalition or blackmail potential (alternately against ND and SYRIZA) in order to remain politically relevant.

From the internal and external supply side, the three-pronged approach of SYRIZA in the appropriate structure of opportunity overturned an established balance of power in party competition. And while this articulation was associated with the emergence of a new dynamic leadership in SYRIZA, the contracted space of the centre left was shared among many minor players and many leaders, and each change of leadership also reflected points of strategic refocus: Papandreou was forced to ally with ND; his successor Venizelos deepened this collaboration; Gennimata in turn acknowledged that collaboration was more detrimental than beneficial, without clearly distancing himself from an eventual new government coalition with ND in the near future.

The crisis was the decisive external/situational shock that disturbed the established equilibria. The contrast between a populist-antisystem-Eurosceptic profile focused on hard materialist issues favoured the ascent of SYRIZA, as opposed to the unwavering Europeanism and unfashionable post-materialism that PASOK maintained while accepting austerity at a great cost.

SYRIZA's ‘U-turn’ in 2015 modified these parameters: SYRIZA directed its anti-system stance against the ‘old’ political system, having made peace with the creditors and now trying to persuade both voters and creditors of its pragmatism; the centre-left players were exerting political pressure, doubting the sincerity of SYRIZA's reorientation. It is clear that the future strategic paths are still developing. The prospect of further convergence would be facilitated by SYRIZA making a permanent turn to moderation and distancing itself from alliance with the nationalist-populist ANEL, and by the centre left moving definitively away from cooperation with ND. Conversely, SYRIZA's ambivalence towards the centre left is a factor for divergence, as is the possibility that the latter may elect to pursue convergence with ND once more, if that is what would secure its presence in government.

Spain: far away, so close

The successive elections of 2011–16 in Spain weakened the bipartisan divide between Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE – Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party) and Partido Popular (PP – People's Party) that had existed since 1977 (Orriols and Cordero Reference Orriols and Cordero2016) and were also marked by a steep drop in the combined electoral percentages of the two ruling parties. Financial stagnation bred dissatisfaction against the ‘old’ political system, empowering two emerging ‘challengers’: the inclusive populism of the left-wing radical Podemos and the moderate rhetoric of the centrist Ciudadanos.

Almost identical to the Greek case, in Spain the radical left became massively popular very rapidly. The appearance of Podemos was the outcome of the need to bring together the demands of the Indignados in a new political configuration – something which the moderate Izquierda Unida (IU – United Left) was unable to accomplish (Ramiro Reference Ramiro2016) – and the rejection of old ‘institutional conservatism’ (Rodríguez-Teruel et al. Reference Rodríguez-Teruel, Barrio and Barberà2016). Podemos used populism both as a tool of political analysis and as a lever for social mobilization (Zarzalejos Reference Zarzalejos2016). At the same time, it sought progressive alliances not only to increase its institutional legitimacy but also to consummate a ‘constitutional modernization’. It adopted a Spanish version of the ‘Historical Compromise’ in order to invest its programme with historical depth (Iglesias Reference Iglesias2015a). Thus there emerged a heterogeneous organization that combined Manichaean rhetoric with programmatic moderation, an attachment to social movements with faith in parliament, and Latin American populism with the Eurocommunist tradition (Iglesias Reference Iglesias2016a).

The PSOE, however, continued to be the predominant progressive party, demonstrating its strong societal roots, historically associated with the smooth transition to democracy, as well as Spain's modernization (Kennedy Reference Kennedy2013). Nevertheless, its electoral disintegration due to its privatization policies, deregulation of the labour market and cuts in welfare came as a ‘natural’ development (Field Reference Field2013); it was left out of power and its vote share became fixed at 20–25%.

Izquierda Unida was the main actor to the left of social democracy before Podemos. Shaped by the Eurocommunist Partido Comunista de España (PCE – Communist Party of Spain) in 1986, it followed aggressive tactics towards the PSOE. The limited success of this strategy led to reorientation: in 2004, the IU voted in favour of the Socialist Zapatero government. In the crisis, the IU pursued cooperation at the local/regional level with the PSOE (Andalusia), while ensuring that the channels of communication with all left-wing forces were kept open.

But it was Podemos that succeeded in broadening its audience, and its electoral percentages duly increased. Its rise was attributed to the radical responses it gave during the Spanish crisis and to the leading figure of Iglesias (Rodríguez-Teruel et al. Reference Rodríguez-Teruel, Barrio and Barberà2017). Podemos started its transformation into an office-seeking party ‘knocking at the door’ of power precisely when the PSOE seemed to be losing its ‘governmental mentality’. From that point on, the PSOE would be accused of adopting a neoliberal doctrine and of being overly tolerant of the conservative PP. At the same time, Podemos was attempting to forge its identity as a progressive, governmental power, while still claiming the traditional social democratic space (Iglesias Reference Iglesias2015b). Competition was often expressed as an intense conflict centred on Spain's place in the EU. The PSOE made sure it defended its inheritance, emphasizing its European orientation against the ambivalence and inexperience of Podemos. Conversely, Podemos embraced a soft Euroscepticism, demanding disengagement from the neoliberal path set by domestic and European elites, without raising the issue of exiting the eurozone (Iglesias Reference Iglesias2015c).

Podemos's main goal was to create a single progressive pillar against the dominance of the conservative PP (Iglesias Reference Iglesias2016b). Convergence with the PSOE at this level was contingent exclusively on the withdrawal of its support for austerity policies and its commitment to radical constitutional changes such as the recognition of Spain's multinational character and the possibility of referenda in autonomous regions (Iglesias Reference Iglesias2015d). In such regions the party's policy principally aimed at ousting the PP from local governments – which, however, did not receive the expected response from either the IU or the PSOE.

The 2014 European elections confirmed the scattering of the ‘progressive’ vote, with the PSOE securing only 23%, the IU 10% and the newly emerging Podemos 7.98%. In the 2015 regional and national elections, unlike the PSOE, whose downward spiral continued, Podemos saw its strength jump to 20.68%, which realized its ambition to overtake the Socialists (‘sorpasso’). The announcement that elections would be held in June 2016 found the parties blaming each other for their inability to form a government.

The pre-election climate changed significantly when it was decided that Podemos would participate on a single national ticket with the IU under the name Unidos Podemos. Leading members of the IU such as former Secretary-General G. Llamazares opposed this collaboration and in Podemos disagreements were expressed by the so-called erejonistas, who, following the party's ‘number 2’, Íñigo Erejon, felt that such collaboration unjustifiably left PSOE out of the alliance. The Socialists, on the other hand, who saw that this polarization between left and right did not favour them, sharpened their criticism of Podemos's anti-system rhetoric and the conservatism of the PP (Galindo Reference Galindo2016).

Finally, the PP managed to increase its strength to 33% and PSOE remained in second place, thwarting the sorpasso from Unidos Podemos. The latter remained in third place, with 1 million fewer votes than Podemos and the IU had won separately in 2015. The following period found the Socialists under Pedro Sanchez constructing a consensual profile towards the radical left with the ultimate goal of establishing a progressive majority in both parliament and senate (Sanchez Reference Sanchez2016a, Reference Sanchez2016b).

This course was abruptly halted when the moderate wing and old guard of the PSOE removed Sanchez from the party's leadership, blaming him for courting the ‘dangerous’ Podemos and prolonging instability through his refusal to participate in a government coalition led by the PP. The distance from the left-wing party widened; the PSOE facilitated the formation of a government by parliamentary abstention. Then the situation changed again, this time with the return of Sanchez to the party leadership. The PSOE adopted a clearly progressive agenda, spearheaded by anti-cyclical policies. It acknowledged the failure of austerity policies, establishing a permanent committee for dialogue between the Socialists and Unidos Podemos.

The Catalan referendum disrupted their relationship yet again and exposed the disagreements caused by the division that pitted the centre against regions, something that is most critical in Spain. Podemos argued that the referendum was legitimate, but did not recognize the binding nature of the vote. The PSOE, by contrast, opposed the organization of the referendum from the outset and defended the unity of Spain.

In the context of this competitive symbiosis, Sanchez's second in-party victory worked as a catalyst for convergence, signifying a break from the alliance with the PP and highlighting the opposition of the party's base to the ideological shift towards the liberal centre. That led to a stepping up of cooperation within parliament, not only for the ouster of Rajoy on the grounds of corruption – in a no-confidence vote with the support of Podemos – but also for the 2019 budget and the highly symbolic removal of Franco's remains from the Valley of the Fallen. As a result of these developments, the PSOE staged a comeback to power.

The interaction between Podemos and the PSOE does not point clearly towards either conflict or convergence. On the contrary, continuing volatility has been generated by the parties’ positions concerning political alliances, which are conditioned by internal divisions within each party and/or by ‘crises within the crisis’ (corruption, Catalonia). At the same time as the prospects for convergence are being projected on the basis of progressive economic choices and a materialist anti-austerity agenda, along with the deepening of social and civil rights and the overcoming of neo-liberalism (rejected by both), the conflict over the Catalan issue remains intense. Spain's place in the EU does not seem to be a critical factor. Instead, the anti-system populism of Podemos as opposed to the mainstream, moderate orientation of the PSOE is a more crucial parameter, although both are being challenged by internal party dynamics. In Spain, too, the social democratic party and its future strategy depend on which direction best secures relevance and ideological identity: joining the conservative right and forming a ‘grand coalition’, or further approaching the radical left.

Portugal: brothers in anti-austerity government

The Portuguese case has a distinctive feature: the convergence between social democracy and the radical left is fact. Indeed, Bloco de Esquerda (BE – Left Bloc) and Partido Comunista Portugues (PCP – Portuguese Communist Party) extend parliamentary support to the Socialist minority government (Partido Socialista – PS) in return for the implementation of a ‘minimum’ joint programme. This is definitely a first in Portuguese political history. The PS is considered a typically office-seeking ‘Third Way’ social democratic party which had consistently maintained its distance from the radical left due to both its ideological positioning and the historical experiences of the turbulent transition to democracy in the 1970s. On the other hand, the PCP has traditionally been considered to be one of the most orthodox communist parties in Western Europe, and the BE was founded in 1999 to oppose ‘neoliberal’ globalization (Lisi Reference Lisi2009). This background could not possibly encourage a convergence between the two party families. But, then, under what conditions did they finally decide to cooperate?

The effects of the international financial crisis on the Portuguese economy were severe. Three successive austerity packages were voted in 2009–10 by the PS and the centre-right Partido Social Democrata (PSD – Social Democratic Party). The failure of the Socialist government to pass the fourth package in March 2011 caused the resignation of Prime Minister Socrates, which eventually led to a right-wing government coalition of PSD and Centro Democrático e Social–Partido Popular (CDS-PP, People's Party). However, the dramatic rise in interest rates of Portuguese bonds led to an Economic Adjustment Programme (usually referred to as the bailout programme or Memorandum).

The four-year period that followed had major implications for the political system. They can be attributed to the assertion that the Coelho government had moved beyond the popular mandate and to the poor payoff from those sacrifices (Freire Reference Freire2016). Nevertheless, when dissent towards the Memorandum reached high levels (2011–12), new social movements did not emerge; protest was instead expressed through ‘traditional’ institutional paths (Accornero and Pinto Reference Accornero and Pinto2015).

The 2015 election took place within this context of delegitimation. Following Coelho's inability to form a government, the mandate went to the head of the PS. Antonio Costa secured the support of the radical left in parliament for the first time since the transition to democracy, on the basis of programmatic agreements he had signed separately with the BE and the PCP. The key to interpreting this convergence is to be found through an examination of the positions of the parties on critical issues.

On the part of the radical left, the PCP, representative of a rather hard Euroscepticism, argued that the economic crisis in Europe was a consequence of the existence of the EU itself. Thus, it called for the abolition of the Treaty of Lisbon and withdrawal from the euro. Such a move could not be immediate, however: a gradual and well-calculated process of disengagement would be required (PCP 2015). The BE professes a soft Euroscepticism. Its position is critical of institutionalized neoliberalism and austerity. Nevertheless, unlike the PCP, the BE argues that the EU can re-establish itself on the basis of a more progressive balance of power (BE 2015).

On the other hand, the social democratic PS is a Europhile party (PS 2015). But for all its Europeanism, it mounts vigorous criticisms of the EU; in particular it asserts that austerity measures have created an economic and social imbalance which can only be addressed by increasing the cohesion between member states and promoting integration. Within Portugal itself, the PS has rallied around the need to overcome austerity, considering that this policy was a strategic choice by the Coelho government (PS 2015).

The radical left and social democracy in Portugal diverge in significant ways, but converge on a crucial point: they both criticize austerity. Their positions on Europe are quite different, but the BE's soft Euroscepticism is not entirely incompatible with the positions of the PS, which could be said to have adopted a rationally sceptic stance towards the management of the European crisis by Brussels (and/or Germany). There are, though, crucial differences in their views on the economic crisis and the relationship between state and economy. The radical left speaks of the need to restructure the public debt and to nationalize the banking sector. The positions of the PS are poles apart from such a radical approach: the party perceives many of the positions of the radical left as ‘adventurism’ (PS 2015).

The programmatic convergences can be supplemented by ideological and political ones. There has been an ideological shift of right-wing party cadres (PSD, CDS-PP) to the right, and left-wing party cadres (PS, BE, PCP) to the left, resulting in greater polarization but also in a convergence of social democracy and the radical left on the left of the right–left axis (Freire et al. Reference Freire, Tsatsanis, Lima, Voicu, Mochmann and Dülmer2016). Similar indications can be found from Portugal's parliamentary life (Lisi Reference Lisi2016): since 2012 there has been a tendency for socialist MPs to vote more frequently against the Coelho government's draft legislation. From 2013 onwards these indications have become stronger, with the positions of social democrats and radical left coinciding on critical issues (e.g. they voted against the state budget and have demanded an examination of the constitutionality of government bills). It also seems that there is a broad consensus among centre-leftist and leftist voters on the question of social democrats and the radical left forming coalition governments (Freire et al. Reference Freire, Lisi, Lima, Freire, Lisi and Viegas2015).

No less important is the strategic orientations within Portugal's party system. The agreement with the PS has enabled the policy-seeking radical left parties to promote their agenda, and also to prevent the implementation of ‘neoliberal’ austerity policies. But involvement in government policymaking legitimizes these parties as actors who do not evade government responsibilities. The danger that this development entails their ‘absorption’ by the mainstream parties is not significant, since these policies are in line with their distinct, radical left identity.

On the other hand, the office-seeking social democracy sought to remain a key governmental actor and to avoid staying out of office for a prolonged period of time. The PS's choice to work with the radical left enabled it to form a minority government and gain access to the symbolic and material resources of the state. Moreover, the need for a distinct identity within the party system also applies to the PS. Indeed, cooperation with the radical left on the basis of a common anti-austerity agenda enabled it to differentiate itself from the conservatives’ governance.

The fact that the PS failed to win the 2015 elections – that is, its inability to capitalize on social dissatisfaction after four years of austerity imposed by the right-wing coalition – was a crucial factor in its decision to cooperate with the left. This election result was a shock to the PS and during its exploratory mandate to form a government, the PS leadership expressed fears of a possible collapse of the party's legitimacy and the loss of its distinct identity if it chose to support a government of the right-wing coalition, not to mention if it followed PASOK's example and participated in it. In Portugal it was precisely the weakening of social democracy that forced it to adopt a strategy of convergence with the radical left – a political cohabitation that appears to have been mutually beneficial.

France: tous contre tous

France has not been subjected to a fiscal consolidation regime. Nevertheless, the period of the crisis radically altered its party system, with Marine Le Pen of the Front National (now the Rassemblement National) coming to prominence and the socialists disintegrating in the presidential elections of 2017.

Historically, the relationship between the left and the Socialists has been a collaborative struggle for hegemony, from the ‘Programme commun’ which in 1981 led to the Parti Communiste Français (PCF – French Communist Party) taking over four ministries under the Mitterrand presidency up to the ‘Gauche Plurielle’ under Jospin in 1997–2002 (Bell Reference Bell and Evans2018). The PCF was the largest component of the Front de Gauche (FDG – Left Front), which was created in 2012 in the run-up to the presidential election, with Jean-Luc Mélenchon as candidate, originating from the Parti Socialiste (PS – Socialist Party). The idea dates back to 2005, and the referendum on the European constitution, when Communists and dissenting Socialists entered into discussions on possible collaboration on the common ground of a soft Euroscepticism (Damiani and De Luca Reference Damiani and De Luca2016).

In 2012, François Hollande was elected president of the Republic, with Mélenchon finishing fourth, after Marine Le Pen. Although Hollande was elected on the basis of a policy triptych ‘care – real equality – fiscal revolution’ (Hollande Reference Hollande2012), he quickly abandoned his ambitious programme, at a time when the crisis was expanding throughout the eurozone and France was increasingly retreating in the face of the hegemonic dynamics of Germany.

Popular disapproval of the Hollande presidency gradually emerged. In the 2014 European elections (PS 13.98%, FDG 6.33%) Hollande was accused of being incapable of leading the French economy to recovery as well as a ‘betrayal’ of his promise to combat social inequalities (Shields Reference Shields2016). On the other hand, within the FDG, many were uncomfortable with the personalized strategy of the fiery populist orator Mélenchon.

Hollande's flagship reforms aiming at opening up the economy and deregulating the labour market (Macron Law, El Khomri Law) led to unprecedented levels of dissatisfaction. The government needed to resort to Article 49-3 of the Constitution in order to endorse these reforms, bypassing the parliament. In the case of the labour reforms, the entire trade union movement was opposed, with a large part of the left wing of the PS (frondeurs) objecting the reform and even putting forward a motion of no-confidence co-signed by MPs of the FDG.

It was a point of no return for the PS. A government-oriented party turned into the weak link of the political system, with its parliamentary group deeply divided and with centrifugal dynamics among its executives, militants and voters. At the same time, France was facing the shock of the rise of Lepenism. Arnaud Montebourg and Benoît Hamon were both candidates at the PS's primaires and members of its left-wing faction that had opposed the El Khomri Law which was seen as leading to a significant deregulation of the labour market; they openly declared themselves in favour of an approach to the PCF and the FDG.

At the primaires Benoît Hamon prevailed against Manuel Valls. His programme was essentially a repositioning of the PS to the left; an attempt to get back to the set of ideas with which voters had become disillusioned after Hollande's quinquennat. In his manifesto Hamon sought to revive the distinction between progressive and conservative-nationalist forces and to boost expansion of the welfare state (a universal basic income), while expressing a vivid scepticism at the course of European integration, along with proposals for strong reforms in Europe (a parliament for the eurozone) (Hamon Reference Hamon2017). But it was too little too late.

The PCF, on the other hand, took a stand in favour of all left-wing forces collaborating (PCF 2016). In the presidential election it was divided over supporting the candidacy of Mélenchon, who had lost no time in presenting (if not imposing) his independent candidacy under the title of La France Insoumise. The PCF is a minor political actor but also a historical and well-structured moderate party, inspired by soft Euroscepticism which aims at changing the neoliberal orientation of the EU and redressing its democratic deficit (Boccara et al. Reference Boccara, Durand and Dimicoli2016); this profile, however, was easily overcome by the dynamics of Mélenchon's highly personalized and mediatized campaign.

Mélenchon led an aggressive vote-seeking campaign focused on his charismatic persona, clearly compatible with the personalized presidential election system. His strong populist/anti-system message was reflected in his manifesto La Force du peuple: a radical contestation of the Fifth Republic, the ‘people’ against the ‘elites’, the defence of France's national/economic sovereignity (souverainisme), scepticism towards the EU, which is purportedly ‘dominated by Germany’. In the same document one finds ‘Plan B’: a hard Eurosceptic line. If the project of laying a new foundation for Europe fails, France should freeze its contribution to the EU budget, impose capital controls and henceforth regard the euro as a ‘common but not single’ currency (Mélenchon Reference Mélenchon2017a). Mélenchon invited Hamon to break with the ‘ancien monde’, that is, with the mainstream system profile of the PS (Mélenchon Reference Mélenchon2017b). His ambition was to overturn completely the balance within the French left – something he succeeded in doing.

Paradoxically, the great protagonist of the presidential election also came from the PS: the charismatic leader of the En Marche movement, Emmanuel Macron. A former minister of François Hollande, Macron too animated a highly personalized political initiative, an anti-system message that explicitly went beyond left and right. Macron's discourse was clearly pro-European, and his campaign was geared to the reforms that would liberate the French economy and labour market from the chains of state regulation – something like a continuation and deepening of the erstwhile Hollande agenda (En Marche 2017; Macron Reference Macron2016).

In the presidential election of 2017 Hamon collapsed (6.36%) and the PS was added to the social democratic parties hit by ‘Pasokification’. Mélenchon gained 19.58% of the vote and successfully emerged as the new powerful player of the French left. In the run-up to the second round, the PS and the PCF offered their support to Macron against the threat of the extreme right; Mélenchon refused to do so, aiming to preserve his anti-system profile but risking a clear break with his former allies. After the parliamentary elections, having failed to be elected even as an MP, Hamon abandoned the PS to establish his own ‘Mouvement du 1er juillet’, which aspired to fill the gap left by the rollback of the socialists. On the other hand a significant number of PS cadres moved to En Marche. The French left thus appears more fragmented than ever. In view of the 2019 European elections, the PCF gave an open invitation to all parties to collaborate, and Hamon favoured a partnership with the PCF. Mélenchon, however, wanted to buttress further his strong position as the alternative to Macron, making contact with the left-wing of the PS, which after the defeat of 2017 was trying to rebuild its profile.

Comparative findings and discussion: different paths lying ahead

A comparative analysis of the four case studies conveys a complex picture. The crisis of 2008 proved to be a crucial ‘external shock’ that was felt first in countries under economic adjustment programmes (Greece and Portugal), and coincided with political crises and ‘crises within the crisis’: the rise of the far right in France, corruption and Catalan/corruption crisis in Spain. In this critical juncture, both established and emerging political actors seek new strategic responses and modify their profile.

All in all it appears that mainstream social democratic parties have been shaken up, but as their courses are conditioned by previous path dependencies, they find it difficult to adjust their strategy with anything like the required rapidity. They remain in crisis and/or fragmented (Greece, Spain and France), with Portugal being the only example of successful readjustment. On the other hand, the challenger parties of the radical left – precisely because they belong to a less cohesive political family – have been able to take advantage of the emergent opportunities more flexibly. They have also presented more persuasive responses to political demands and have acquired a more relevant position than in the past, approaching actual governance rather than merely representing social protest. But their strategic shift does not have uniform characteristics and often encounters limits of its own.

After 1989 the radical left parties developed a relationship of competition and cooperation with the dominant Socialist parties, but only in France is a clear tradition of collaboration to be observed, dating back to the Popular Front of 1936. Recent history has not favoured further convergence between the two party families: in all four cases the social democratic party was the stronger player in the electoral competition, whereas the radical left parties were minor players. But the economic crisis, together with the major crisis of political confidence (and the rise of the far right in France), destabilized the respective two-party systems in which the parties of a radicalized ‘Mediterranean’ socialism had been one of the two key pillars since the transition to democracy in Spain, Greece and Portugal and since 1981 in France.

It is thus the critical breakdown of decades-long stable party systems, along with an ‘electoral epidemic’ and disintegration of the centre left in many competing polities (as in the Greek and French case) that fostered a certain interaction between the two families. To this institutional factor one must add the fact that the radical left took advantage of the opportunity that presented itself in the form of the ‘movements of the squares’ and either radically redefined their former profile (SYRIZA) or emerged as new actors (Podemos) and ventures centred on individuals (Mélenchon). These external supply-side factors favoured convergence in the sense that the well-established unequal relationship between the two players was partly overcome by the crisis, on the one hand due to the ‘Pasokification’ of social democracy and on the other due to the strengthening of the radical left, which took advantage not only of the adversary's recession but also of the social tension (see Table 2). In this context convergence is also reflected at the institutional level in various forms of cooperation inside parliament: the radical left supporting minority Socialist governments (Portugal and Spain), Socialists supporting bills on civil rights introduced by radical left governments (Greece), a common understanding between the left and the frondeurs of the Socialist party (France).

Table 2. External Supply-Side Factors of Convergence or Divergence

But how did the radical left exploit this double window of opportunity (economic crisis and destabilization of party systems) and what effect did this have on the social democratic parties, from the internal supply side? The reorientation of the radical left was facilitated by the emergence of a new generation and type of leadership (see Table 3). The personalization of politics is a trend dating from before the crisis, but it now appears, additionally, to be intensely populistic in style, complemented by rather loose organizational structures (SYRIZA, Podemos, Mélenchon) which were not to be found in more ‘traditional’ participatory parties (IU and PCF). This enabled the new leaders to steer the ship with greater determination and flexibility – even though there were internal divisions over coalition strategy towards the PSOE in Podemos and between the PCF and Mélenchon in France. On the other hand, this new equilibrium has created internal shocks within social democratic parties and also their gradual change of trajectory. It is no coincidence that in most cases there has been fragmentation at the leadership level and/or in organizational forms: a leadership crisis in the PSOE, successive changes of leadership and party experimentation in Greece, the collapse of the PS at the end of Hollande's five-year term in France. The former organic link with the social movements and the unions was weakened, which in turn prevented social democracy from promoting an updated social democratic compromise, while at the same time the radical left was renewing its links with social radicalism.

Table 3. Internal Supply-Side Factors of Convergence or Divergence

These factors play a dual role in what concerns our argument: they escalate the competitive relationship between the two families (as the minor player gains in strength and the dominant party is destabilized), but at the same time they reduce the distance in their ideological profile and strategic choices. The major strategic shift of the radical left was that from policy-seeking parties expressing social protest they mutated into forces with a horizon of governance and an increasingly intense office-/vote-seeking character. Rather than entrenching themselves behind a strong protest-party profile (which had been the choice in the 2000s), they were confronted with the question of power. The strategy of forming alliances was the common thread – that is, the convergence of forces within the radical left (Podemos and the IU, Bloco and the PCP, the PCF and Mélenchon), the opening to social democratic forces in an anti-austerity or anti-right direction, or the paradoxical Greek case, where SYRIZA formed a coalition with smaller radical left parties and movements and later a government in alliance with a party of the populist right. By representing social protest, these parties gained enough strength to acquire coalition potential against their Socialist ‘enemy brothers’ (leading in Portugal, and eventually in Spain, to governmental cooperation), or even to directly threaten to unseat them as dominant parties on the left side of the spectrum (France, where Mélenchon preferred an autonomous course to the strategy of coalition with the Socialists that the PCF favoured), and actually to succeed in doing so, emerging as major governing powers (Greece, where it was only after its compromise that SYRIZA undertook to approach the centre left).

At the other end of the spectrum, social democrats realized that if they have a strong radical left to their own left they cannot retain political hegemony in an alliance with right-wing parties (Greece, Spain and Portugal) or by focusing on their own distinguishing features, which in the 1990s might have been satisfactory responses but in current conditions are not appropriate (France, Spain and Portugal). It is thus a common trend among the social democratic parties we have studied to opt out of collaborating with conservatives in order to remain a relevant political force with government (Spain, Portugal) or coalition potential (as in Greece, where the fragmented centre left seems to have moved away from its strategic collusion with the right, though it has not converged with SYRIZA). The exception here is France, where a minority part of the Socialists turned to the radical left as a potential ally and another shifted towards the centre.

But the most critical factors of convergence/divergence in the countries under consideration are the demand-side factors which generate immediate political and ideological responses to the ‘external shock’ of the crisis (see Table 4). These factors work in a seemingly paradoxical way. As a first step, they seem to increase the distance. In essence, however, they destabilize the established ideological identities and provoke critical displacements: as the radical left approaches government it comes closer to more realistic positions, mitigating its anti-system Eurosceptic profile; social democracy, in contrast, breaks with its previous strategic paths in order to remain relevant and maintain its government potential. It adopts an anti-austerity stance and ventures a certain criticism of European integration as it evolves in the crisis-ridden EU.

Table 4. Demand-Side Factors of Convergence or Divergence

The key to the advance of the radical left is precisely that it has responded appropriately to the demand-side factors. It reinforced its anti-system profile against the mainstream parties in office. A strong anti-system populist rhetoric was added to this, flexible enough to censure the dominant economic policy and/or the ‘established’ political elites considered to be corrupted (SYRIZA, especially after the ‘capitulation’ of 2015, Podemos against the PP) and to carry out a clear turn to a strongly materialist and soft Eurosceptic programme that at times morphed into hard Euroscepticism (in SYRIZA's hypothetical ‘Plan B’ to break with Greece's creditors or Mélenchon's possible return to the franc; the traditional hard Euroscepticism of the Portuguese PCP proved to be more pragmatic). Indeed, this new political style has clearly prevailed over older, more moderate forms of radical left-wing politics (the ‘Tsipras generation’ vs traditional SYRIZA cadres, Podemos vs the IU, Mélenchon vs the PCF).

In this way, the radical left seized issue ownership from the hands of social democracy, which had been transformed into a ‘liberal’ and post-materialist mainstream power in an overly consensual and depoliticized alliance with the conservative-liberal right (Cronin et al. Reference Cronin, Ross, Shoch, Cronin, Ross and Schoch2011). If its unconditional Europhilia and inability to propose an alternative to the predominant ordoliberal austerity is added to all the above, we have the basic reasons for its suddenly finding itself threatened by its ‘enemy brother’ for the first time since the collapse of the socialist camp.

Only the Portuguese socialists diagnosed the change of climate, and that only after coming within a hair's breadth of not winning an election. They quickly reassumed the position of a relevant governmental party, sceptic of the fiscal policy imposed by Brussels and espousing the anti-austerity agenda of the radical left by jointly forging with them a front against the right. In Spain, Sanchez's plan for disengagement from the scandal-ridden PP led to his being removed by the PSOE's old guard. He nevertheless staged a comeback, making a Portuguese-style anti-austerity turn combined with an anti-corruption offensive against the PP, which ended in a socialist government with the backing of Podemos. In France, Hamon represented a mild, belated shift to the left for the Socialists, but the bet was won by Macron, who proceeded with a radical break from the PS via an anti-system profile that only later started moving towards the centre.

The opposite also holds true: notwithstanding its explosive rise in some cases, the radical left soon encountered the limits of its anti-system Eurosceptic profile. It was unable to keep its anti-austerity promises, particularly within the narrow margins permitted by the complex ‘conservative’ institutional edifice that is the EU (Moschonas Reference Moschonas and Callaghan2009), at least in so far as it refused to adhere to hard Euroscepticism. At the same time, their Achilles heel is exactly what social democratic parties have claimed for themselves: governmental competence and pro-European realism. SYRIZA's pragmatic shift/compromise has been the most striking example of this. The limits of the radical strategy were also revealed by Podemos's inability to achieve the sorpasso over the Socialists in the context of a national crisis such as that of Catalonia. The same is true of Mélenchon's highly ambiguous strategy (Plan B). It is no coincidence that, with the exception of Mélenchon, who is nevertheless currently being established as the main left-wing opposition to Macron's ‘radical centrism’, the forces of the radical left pragmatically seek (in Spain and Greece) or maintain (in Portugal) ways of cooperation or cohabitation with the socialist family at the national and/or European level.

Conclusions

The answer to the opening research question seems positive: the critical juncture of the crisis has modified the quasi-frozen dynamics between the radical left and social democracy. In the four countries we have examined, all of which have experienced in a particular – albeit not the same – way the economic and political crisis of recent years, the respective parties have seen significant ideological and strategic reorientations.

Nevertheless, there is no unilateral answer to the question of whether the crisis has brought those parties closer together or moved them further apart. New demand-side factors have emerged, and previously static supply-side factors are being modified, some exacerbating competition and others favouring symbiosis; or initially increasing the distance and then bringing them closer together. Hence, ‘competitive symbiosis’ is an appropriate term to describe the antinomies of this perennially fluid relationship.

Certainly, the displacements caused by the crisis and the electoral-government epidemic in the European South cannot constitute a generalized norm for the two party families as a whole. An in-depth comparative study on a Europe-wide scale would probably indicate a wide variety of relations, ranging from absolute stability to spectacular overturn. Besides, in terms of party families, there are more exceptions than rules. What is confirmed, though, is that research should focus not only on how the two ‘enemy brothers’ change but on how they evolve in their interactions.

The reorientation of the radical left from protest to governance, and the readaptation of social democracy as it breaks with paths followed since the 1990s, are major moves that can be better understood in terms of how they intertwine with each other. This would facilitate avoidance of the essentialist trap of an allegedly immutable social democratic/radical left ‘identity’. The historical phase in which we find ourselves clearly shows that one identity is constantly being reformulated in its ‘competitive symbiosis’ with the other – in the enduring competition on the terrain (champ) of political parties, as Pierre Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu1982) would put it, where political and ideological relations remain stable yet constantly morph into critical historical junctures via their own interaction.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge their debt to the three anonymous reviewers of the journal, whose feedback was very constructive and has substantially enhanced the paper. Also, they would like to thank their colleagues Christos Roukos and George Papoulias for their contribution at an early stage of this research project.