Cabinets mark a structure at the very heart of the governing machine that, in many countries of the democratic world, have belonged to the efficient, not just the dignified, parts of the living constitution.Footnote 1 If to differing degrees, this remains true even after the long series of scholarly swan songs on the end of cabinet governance that have been published since the late 1960s (for an overview and assessment, see Foster Reference Foster2004). Indeed, it is fascinating to see that those cases widely referred to as showcases of a seminal decline of cabinet government in the past, notably the UK, are the same as those that have more recently come to witness a powerful return of the cabinet (e.g. Bell Reference Bell2017). Recent comparative research confirms that cabinet government is a notably resilient and viable regime at least in many of the Westminster democracies (see Weller et al. Reference Weller, Grube and Rhodes2021), but arguably well beyond. If, as Rudy Andeweg suggests (Reference Andeweg, Bakvis, Rhodes and Weller1997: 83), ‘multiple representation’, which is typical for multiparty coalition governments in complex multiparty regimes, tends to strengthen rather than weaken collective forms of government, cabinet government in many contemporary democratic regimes may be actually facing a bright future.

Cabinets allow for both stability and flexibility. The latter concerns the possibility of (more or less) silent makeovers of an incumbent government by replacing or relocating cabinet members while governing. Such cabinet turnovers matter in terms of representation, power and/or policymaking, to the extent that the cabinet matters in a given regime. The political importance of cabinets is obviously not confined to parliamentary democracies. Across Latin America, cabinets are part and parcel of presidential government (e.g. Albala Reference Albala2021). There is also a growing literature looking more specifically into issues of cabinet or ministerial turnover in presidential regimes (e.g. Camerlo and Martínez-Gallardo Reference Camerlo and Martínez-Gallardo2018; Perissinotto et al. Reference Perissinotto, Codato and Gené2020). Occasionally, cabinet and ministerial turnovers have been studied even for regimes from beyond the family of liberal democracies (e.g. Lee and Schuler Reference Lee and Schuler2020; Quiroz Flores Reference Quiroz Flores2017). Still, when understood as a concept of ‘governing together’ (Blondel and Müller-Rommel Reference Blondel and Müller-Rommel1993), cabinet government is essentially a defining feature of parliamentary government, if not synonymous with it (see Blondel Reference Blondel, Blondel and Thiébault1991: 5).

While cabinets' potential for combining institutional stability with political flexibility is widely acknowledged, there are forms of changes at cabinet level that are not covered by established notions of what constitutes ‘one cabinet’ in comparative political research. Most scholars agree that a cabinet terminates when: (1) a general election occurs; (2) the prime minister changes; (3) and/or if the party complexion of the cabinet changes; and some scholars consider (4) government resignations as another criterion (see Vercesi Reference Vercesi, Andeweg, Elgie, Helms, Kaarbo and Müller-Rommel2020: 440–441). Thus, even major changes to the cabinet team, including those involving a change of party control of cabinet departments in otherwise stable coalition governments, are not considered to mark the beginning of a new cabinet. Instead, changes in the composition of the cabinet, or its departmental structure, taking place within the lifetime of one cabinet (as defined in the way highlighted above), are widely referred to as ‘cabinet reshuffles’.

The political nature of reshuffles is generally assumed to be understood also by political observers outside the world of Westminster. However, this may well be an illusion. As veteran British political analyst Peter Riddell recalls, ‘When I was Director of the Centre of Government and wanted to discuss reshuffles with a visiting delegation from Germany, it was very difficult to get the concept over to them, because they simply did not understand what we were talking about’ (Riddell Reference Riddell2019: 196). This comes as a powerful reminder that such changes remaining below a level that would indicate the formation of genuinely new cabinet (according to the terms set out above) can take rather different shapes and forms, and flow from fundamentally different ‘governing philosophies’. Moreover, changes in the organization and make-up of evolving cabinets may not just reflect different motives and causes but can also have substantially different effects.

The extant literature has largely ignored this variety, either by investigating causes and rationales of cabinet reshuffles without making substantial distinctions between episodes of personnel change, or by focusing only on very specific manifestations of ministerial turnover (e.g. Bäck and Carroll Reference Bäck, Carroll, Andeweg, Elgie, Helms, Kaarbo and Müller-Rommel2020; Bäck et al. Reference Bäck, Meier, Persson and Fischer2012; Kam and Indriðason Reference Kam and Indriðason2005). This article seeks to take the first steps towards closing this gap and advancing the comparative study of cabinet reshuffles by reaching beyond the well-established tradition of analysing reshuffles in Westminster-type democracies. At the centre of this piece is the development of a heuristic typology of cabinet reshuffles that distinguishes between the different modes and scopes of reshuffles, and particular combinations of the two. We seek to answer two research questions: (1) which analytical dimensions define cabinet reshuffles? and (2) how many empirical types of reshuffles can be reasonably distinguished? In doing so, we do not aspire only to bring some order to the study of an exceptionally complex and dynamic element of the political executive. Rather, the ultimate aim of our effort is to help prepare the ground for more substantive and precise assessments of the effects of cabinet reshuffles by acknowledging that not all reshuffles are the same. Our premise is that different types of reshuffle are likely to have different effects (differences of both kind and degree), and that – to understand the effects of past reshuffles and to gauge the possible effects of prospective reshuffles – a conceptual framework capturing the fundamentally different nature of individual reshuffles is necessary.

The next section highlights the importance of cabinet reshuffles in light of the international literature. Moreover, it revisits this literature with the aim of developing a novel definition of cabinet reshuffles that will be used for devising a typology of reshuffles. This typology will be presented in the third section, alongside some illustrative examples. The fourth section then demonstrates the discriminating power of our conceptual distinctions through a systematic comparison of the ‘reshuffle landscapes’ in four large West European countries. The closing section discusses the findings and their implications, and identifies avenues for future research.

Cabinet reshuffles: conceptual challenges and empirical relevance

Changes in the make-up of the cabinet team tend to be political events accompanied by a maximum of public attention. In ever-more mediatized and personalized political environments, political events involving personnel matters have come to enjoy an unrivalled amount of attention. The presentation of a team of ministers after an extended election campaign (and, in many countries, lengthy negotiations between different parties) regularly marks a genuine highlight of the government-building process in terms of media attention and public excitement, and pretty much the same is true for changes at the level of cabinet ministers that occur during a government's term. As Pekka Isotalus and Merja Almonkari (Reference Isotalus, Almonkari, Strömbäck and Esser2015: 52) note, ‘any reshuffle of party leaders or ministers is seen as interesting in the media’. Even mere speculation about possible reshuffles that eventually do not materialize may keep observers rather busy.

However, there is good reason to believe that there is more to cabinet reshuffles than shallow media fuss about some new and other ‘all-too-familiar’ faces. Indeed, there is a rich, if widely scattered, literature on the politics of cabinet reshuffles. In accordance with the more particular agenda of this article, the literature review below focuses on the different key features of cabinet reshuffles and the motives and goals shaping the actions of those in charge. Before that, a reasonably clear-cut definition of cabinet reshuffles is in order.

Definition

To begin, we opt for an inclusive understanding of reshuffles – that is, we consider minor changes that are confined to one department and leave the established pattern of party control intact genuine reshuffles (see also Alderman and Cross Reference Alderman and Cross1987: 1). This marks an important contrast to the influential definition of cabinet reshuffles suggested by Christopher Kam and Indriði Indriðason, as ‘any change in ministerial personnel or responsibilities that affects more than two officeholders and at least two portfolios’ during the lifetime of an existing cabinet (Kam and Indriðason Reference Kam and Indriðason2005: 329). The two authors justify their choice by invoking the resistance to causal analysis of instances of isolated ministerial change. This may be mark a convincing argument in the specific theoretical and methodological context in which Kam and Indriðason operate. Yet, generally, we believe that comparative political research should confront the apparent challenge that real-world contingency continually threatens to frustrate scholarly efforts at the level of theory-building (see Shapiro and Bedi Reference Shapiro and Bedi2007). More specifically, we believe that a comparative inquiry into the politics of cabinet reshuffles has to account for all cases of ministerial change, even though some of them may be exceptionally difficult to assess.

Another key feature of Kam and Indriðason's definition worth noting in passing is that, unlike most coalition theorists, they do not consider the appointment of a new prime minister to be indicative of a new government, unless the incoming candidate is from a different party (Kam and Indriðason Reference Kam and Indriðason2005: 331). By contrast, we opt here for a definition that conceives of cabinet reshuffles as any change in ministerial personnel or responsibilities during the lifetime of a single cabinet (the latter being characterized by the absence of changes in the office of prime minister, in the party complexion of the government, a general election or the resignation of the full cabinet). In the real-word politics of different democratic regimes, there is a considerable and possibly confusing variety of rules to be accounted for when devising a general definition suitable for comparative inquiry. This is especially true for the rules concerning changes in the office of prime minister. While in Westminster systems and countries based on negative parliamentarism (Bergman Reference Bergman1993) the selection of a ‘takeover’ prime minister (Worthy Reference Worthy2016) can indeed be understood as a strategic party action to ‘reset’ an incumbent government, in other contexts the change of a prime minister formally requires the resignation of the whole cabinet, and a new confidence vote in the parliament. This is the case, for example, in Belgium, Israel, Italy, Japan and Spain. However, notwithstanding these differences, according to our definition any change in the office of prime minister indicates the formation of a new cabinet.

Goals/intended effects

As to the goals, or intended effects, of cabinet reshuffles, at least four threads of thinking can be distinguished.

First off, ministerial turnover has been considered a particular resource for governments, and/or more especially prime ministers, to prolong or to rebuild their popularity by bringing in new faces. There is scattered evidence that reshuffles actually lead to improved popularity scores for the government and/or the prime minister (see e.g. Miwa Reference Miwa2018). While popularity is a general resource that can be helpful in many ways, it is not something necessarily needed by governments in parliamentary democracies all along the way, apart from possible intra-party revolts driven by fears that a soaring unpopularity of a minister, prime minister or the government as a whole may be turning into a major electoral liability. In that case, intra-party challengers may seek to oust an incumbent well before the end of the legislative term. Similarly, in multiparty governments coalition partners may push the dismissal of less important ministers when the government popularity falls, especially if the economic situation is bad (Hansen et al. Reference Hansen, Klemmensen, Hobolt and Bäck2013). Generally, however, it is for the voters to decide if a government's time is up. Thus, reshuffles with the aim of increasing the government's popularity and public support for the government are, ultimately, about keeping the electoral costs of governing – which all administrations come to face sooner or later – down (see Green and Jennings Reference Green and Jennings2017: ch. 5).

A second set of arguments revolves around issues of effectiveness and efficiency, which mark important elements of perceived government performance that tend to shape popularity and approval scores, and perceived levels of legitimacy more generally (see Helms Reference Helms, Andeweg, Elgie, Helms, Kaarbo and Müller-Rommel2020). Most scholars have considered this issue within the framework of principal–agent theory. To the extent that the principal (the prime minister, or the party) controls the politics of hiring and firing ministers, or relocating them within a given administration, cabinet reshuffles offer an instrument against ‘ministerial drift’ (Indriðason and Kam Reference Indriðason and Kam2008), thereby allowing the principal to tighten its grip on the government's policy agenda. However, at the same time, ministerial turnover has been deemed to be potentially detrimental to both the efficiency and effectiveness of the policymaking process as well as the performance of cabinets vis-à-vis other institutions (Adolino Reference Adolino and Scherpereel2021; Perez and Scherpereel Reference Perez and Scherpereel2017),Footnote 2 all due to a possible lack of time for ministers to become familiar with the practices of their department. For example, Thomas Baylis (Reference Baylis2007: 84) has argued that duration in office ‘provides something like a proxy for [personal] effectiveness’; similarly, Wolfgang C. Müller and Wilfried Philipp (Reference Müller, Philipp, Blondel and Thiébault1991: 149) have stressed that staying in power defines the ‘ability to develop and implement policies’. Ministers need some time in office to get used to their job and learn how to deal efficiently with their departmental staff. As Richard Rose has pointed out, ‘[t]he bulk of the first year may … be spent in “learning the ropes” and not in making effective choices’ (Rose Reference Rose1971: 407).

Third, it has been noted that regular changes to the cabinet that offer advances in terms of winning ministerial office to ambitious career politicians in parliament can be used as a powerful incentive to secure reasonably high levels of party discipline (see Kam Reference Kam2009). This argument has been developed in the context of Westminster democracies, with single-party governments and ministers having to be drawn from the pool of parliamentarians.Footnote 3 The latter conditions and features may be largely absent in many other parliamentary democracies, but the general logic of having to keep members of the majority parliamentary party groups reasonably happy throughout a government's term clearly applies to different types of parliamentary democracy (see Depauw and Martin Reference Depauw, Martin, Giannetti and Benoit2009). This includes the more particular challenge for intra-party relations that may arise from the appointment of technocrat ministers at the expense of aspirants from within the parliamentary party groups.

Last, but not least, cabinet reshuffles may be pursued to generate certain policy effects. Traditional wisdom on public policymaking in parliamentary democracies considers the party complexion of the government as a proven key denominator of the public policies that governments make (see Potrafke Reference Potrafke2017; Schmidt Reference Schmidt1996). Therefore, even minor changes of party control limited to one single cabinet department may have discernible policy effects. Moreover, as Despina Alexiadou (Reference Alexiadou2015) suggests, the public policies that governments make also depend on the type of minister (‘loyalist’, ‘partisan’ or ‘ideologue’) that chairs a department, which implies the possibility of substantive policy effects in the course of ministerial turnover even in the absence of change in terms of party control. As Alexiadou concludes in light of an 18-country comparative inquiry, ‘ideologue and partisan social affairs ministers have increased social welfare generosity in the last 30 years unlike loyalists’ (Alexiadou Reference Alexiadou2015: 1078). These findings are suitable to challenge established assumptions in the political economy and welfare state literatures that political parties are homogeneous actors, and that public policies in party democracies can be explained sufficiently by looking at patterns of party control of the government and individual departments alone.

Incentives and capacity of principals

Discussions about the goals of reshuffles imply that there is an actor – a reshuffle's principal – who initiates and leads the change. In parliamentary governments, two possible principals can be distinguished: the prime minister or the party. In Westminster systems where single-party (majority) cabinets are typically led by prime ministers who are also party leaders, cabinet reshuffles are potent prime ministerial tools to sack ‘bad’ ministers (Huber and Martínez-Gallardo Reference Huber and Martínez-Gallardo2008), to disincentivize opportunistic ministerial behaviours (Indriðason and Kam Reference Indriðason and Kam2008) and/or to restore the cabinet's public reputation in the aftermath of ministerial scandal (Berlinski et al. Reference Berlinski, Dewan and Dowding2012). In this scenario, cabinet reshuffles essentially constitute solutions to problematic relationships of power delegation and accountability, in which the prime minister is the principal and cabinet ministers are the agents.Footnote 4

However, in many coalitional contexts (which are not extraneous to Westminster systems), where ministers are also agents of the coalition partners (Andeweg Reference Andeweg2000), political parties often play a major role as effective principals in their own right. This especially applies to countries where institutionally and politically weak prime ministers tend to be moderators or arbitrators rather than particularly vigorous leaders, and whose key function is to accommodate diverging party preferences within the government. Moreover, in coalition governments, one significant constraint on prime ministerial action relates to the fact that the head of government cannot usually ‘fire’ ministers from parties other than his or her own without risking the break-up of the coalition.

Depending on the aforementioned actors' goals, we assume that the prime minister or the party (leader) will seek to activate different forms of reshuffles, shaped by the incentives they face and their respective capacity to reach their goals (see Fleming Reference Fleming2021: 6). In this regard, the literature highlights three main incentives that make the principal likely to generate ministerial turnover. First, voluntary ministerial resignations – either due to force majeure (e.g. health reasons) or for political reasons – usually provoke certain revisions in the allocation of ministerial portfolios (e.g. Dowding and Kang Reference Dowding and Kang1998; Martínez-Gallardo and Camerlo Reference Martínez-Gallardo, Camerlo, Camerlo and Martínez-Gallardo2018: 211). Second, prime ministers and party leaders often dismiss or demote cabinet ministers in response to scandals or other events that undermine the public image of the ministers themselves (Berlinski et al. Reference Berlinski, Dewan and Dowding2012; Dewan and Myatt Reference Dewan and Myatt2007). Finally, several reshuffles are simply ‘discretionary dismissals [or reallocations …] indicating a sanctioning of agency loss or ministerial drift by the [principal … R]easons are policy disagreement, departmental error, performance failure and cabinet [reorganization]’ (Bäck et al. Reference Bäck, Meier, Persson and Fischer2012: 192).

One crucial aspect that distinguishes the three scenarios from one another concerns the principal's stance towards these changes. In fact, only in the latter case is there a real commitment to reshuffle the cabinet at work, irrespective of external events affecting the ministers involved. By contrast, in the first scenario the principal has no more than a ‘favourable attitude’ towards change: that is, a propensity to react to a certain event in the absence of any more particular interest in the issue. Precisely the existence of such major ‘interest’ characterizes the second scenario, however; here, the principal is inclined to act in an attempt to forestall the possible consequences of an unexpected shock, without which the incentive to reshuffle would be too low.Footnote 5

In any case, the breadth and depth of a reshuffle will depend to a significant extent on the power of the prime minister or the coalition party leaders. Only powerful actors facing few checks on their room for manoeuvre can – all else being equal – (re)move a larger number of cabinet ministers who command certain power resources themselves. For example, Thomas Fleming (Reference Fleming2021) has argued that prime ministers need electoral popularity to pursue large reshuffles in Westminster systems successfully. Within coalitions, the say of majority leaders is largely determined by their parties' bargaining position vis-à-vis other (real or potential) partners (Ecker and Meyer Reference Ecker and Meyer2019). Moreover, comparative research suggests that ministers holding key positions within the cabinet in terms of status and power are generally harder to (re)move than the holders of less senior offices (Bright et al. Reference Bright, Döring and Little2015).

The modes and scopes of cabinet reshuffles: the typology

While the specialist literature usually treats all cabinet personnel reorganizations and ministerial portfolio (re)allocations as essentially equivalent manifestations of ‘cabinet change’, we argue that for genuinely comparative inquiries into, and assessments of, the possible effects of cabinet reshuffles in parliamentary systems, a more fine-grained conceptual framework is needed. Based on the literature review above, we posit that the two most crucial dimensions when it comes to capturing the different nature of real-world cases relate to the mode and the scope of a cabinet reshuffle. The former flows from the discussion about the incentives for reshuffling, while the latter builds on the notion of capacity. We believe that the nature of a reshuffle, as to be captured by our two primary dimensions, is likely to have a major independent impact on the effects that different reshuffles may have. This implies that – depending on the principal's preferences and goals, the opportunity structure in place, and the extent to which the course of events can be controlled – principals may consciously opt for different types of reshuffles.

The mode – the ‘how’ of a reshuffle – denotes the level of activism of the principal in initiating and conducting the process. It ranges from a relatively reactive mode to strongly proactive behaviour. In the most reactive version, the principal (either prime minister or party/parties) simply acknowledges an unintended resignation of a minister and hastens to ‘fix’ an emerging vacancy resulting from that resignation. Theoretically at least, a resignation has not always to be followed by a replacement; however, the most common reaction of the principal is to close a ministerial vacancy before too long. Reshuffles due to resignations caused by health reasons, death of a minister or any voluntary resignation, the approval of an individual no-confidence motion or a judicial verdict against a minister falls into this category.Footnote 6 It is worth emphasizing that, according to this understanding, all (truly) voluntary resignations are counted the same – no matter how the ‘inside story’ of a particular case developed (see Fischer Reference Fischer2017: 13). The crucial point to stress here is that the principal did not intend to elicit the ministerial exit.

A higher – intermediate – level of activism of the principal can be distinguished when the principal experiences an exogenous pressure or shock (usually deemed to have detrimental effects), and thus acts in anticipation of further negative consequences to be avoided. In contrast to ‘fixing reshuffles’, where the principal adopts a purely reactive role, these reshuffles are ‘anticipatory’. The most common triggers for this kind of reshuffle are personal scandals, resignation calls from the opposition or unexpected crises that may cause the principal to persuade or urge the involved minister to step down (e.g. Brändström Reference Brändström2015). As pointed out by Jörn Fischer (Reference Fischer2017: 13–14), who distinguishes between push and pull factors driving ministerial turnover, in these cases ministers are being ‘pushed’ by the principal to leave. As more recent research suggests, contemporary ministers, facing unprecedented levels of personalization and mediatization of politics, tend to fall easy prey to scandalization dynamics, and thus are considerably more likely than their historical predecessors to lose their office before the end of a government's term (Garz and Sörensen Reference Garz and Sörensen2021).

Finally, principals can proactively initiate and manage a reshuffle. The typical proactive reshuffle involves changes of one or several ministers that reflect the political will of the principal, in the absence of any major exogenous pressures. In such contexts, the principal controls much of the process. The creation of new cabinet posts falls into this category, as well.

The second fundamental dimension of cabinet reshuffles concerns the scope – or the ‘what’ aspect – of a reshuffle. Large-scale reshuffles have greater weight and potential in the eyes of the public, in terms of policy changes and for the politics of cabinet governance more generally, than reshuffles with a more limited scope. The most consequential reshuffles, for good or bad, are those affecting many cabinet positions and, in particular, affecting the holders of the most important portfolios. Hence, we operationalize the scope as the overall extent of the change in terms of both the share of cabinet ministerial posts affected and their prestige.Footnote 7 The decision on when to speak of a small, medium or large scope is, necessarily, somewhat arbitrary. In fact, the size of parliamentary cabinets around the world ranges from about ten in smaller countries to more than 30 ministers in countries such as Canada, India or Israel. For the sake of comparison and better comparability, we set the thresholds as follows: a small reshuffle is limited to changes in less than 10% of cabinet ministerial positions; a medium reshuffle involves between 10% and 15% of all positions; finally, all reshuffles affecting 15% or more of all cabinet positions and/or high-prestige portfolios will be referred to as ‘large scope reshuffles’. We focus on percentage thresholds in order to mitigate cross-country differences. With regard to portfolios' prestige, we follow Mona Lena Krook and Diana O'Brien (Reference Krook and O'Brien2012: 845–846), who define it in terms of ‘visibility and significant control over policy’; based on their comparative assessment, we classify finance, economy, interior/home affairs, defence and foreign affairs as high-prestige portfolios.

From such a conceptualization scheme, nine types of cabinet reshuffles emerge (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Varieties of Cabinet Reshuffles in Parliamentary Systems

A minor fixing reshuffle denotes the replacement of a small number of ministers after their resignation, affecting less than 10% of cabinet posts.Footnote 8 Myriad incidents of cabinet turnover meet these criteria, and not all of them matter very much in terms of politics and policy, but some might. The case of Lorenzo Fioramonti, Italian minister for education, university and research in the Conte II cabinet, provides an example. After his resignation in December 2019, due to a conflict over the allocation of financial resources to its own ministry, the head of state appointed two new ministers, one for education and one for university and research (Il Sole 24 Ore 2019).

Moderate fixing reshuffles are usually ‘aftershock’ changes, being sparked by voluntary ministerial resignations and affecting between 10 and 15% of ministerial positions. The Norwegian case of two ministers voluntarily resigning together in August 2018 to spend more time with their families is a case in point. In the reorganization of the cabinet prompted by these resignations, Prime Minister Erna Solberg eventually exchanged the heads of three departments (14%) (Reuters 2018a).

Collective resignations are comparatively rare events that usually relate to serious disagreements between the resigning ministers and the prime minister, and/or over government policy. A major fixing reshuffle involving five ministers (16%, including the defence minister) occurred in Italy in the early 1990s. In protest against the new regulation policy for radio and TV communications of the Andreotti VI cabinet, five members of the left-wing area of the largest coalition partner (Christian Democracy) left the government between 26 and 27 July 1990 (Calandra Reference Calandra1996). Major adjustments can also result in the course of resignations of less than 10% of ministers, if a ‘high-prestige’ portfolio is concerned. British Prime Minister Theresa May promoted such a change when cabinet members David Davis and Boris Johnson (then foreign secretary) resigned in July 2018, in opposition to the government's White Paper about future relations between the United Kingdom and the European Union. May replaced both ministers with people who supported her (Dominic Raab and Jeremy Hunt), which ensued the reallocation of two further responsibilities. In Germany, after Ursula von der Leyen's election as president of the European Commission in 2019 and her subsequent resignation as German minister of defence, Chancellor Angela Merkel selected another female candidate, the recently elected Christian Democratic Union (CDU) party leader, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, as the successor to von der Leyen.

A minor adjusting reshuffle is, instead, the substitution of a small share of ministers, activated by the principal in response to an exogenous event and conducted against the will of the agent. For example, in April 2017, the Japanese Liberal Democratic Party's minister for reconstruction Masahiro Imamura resigned, urged by Prime Minister Shinzō Abe because of Imamura's controversial remarks about the 2011 disaster at Fukushima (Yoshida Reference Yoshida2017).

An example of a reshuffle of the moderate adjusting type can be found, inter alia, in India. Simultaneous scandals involving two cabinet members heading two ministries (out of 20 ministerial posts) – Pawan Kumar Bansal (railway minister) and Ashwani Kumar (law and justice minister) – affected the second Singh coalition government in 2013. Facing fervent resignation calls by the opposition, both ministers denied any responsibility or wrongdoing in the first place, but eventually resigned (and were substituted by party fellows) when their party (Indian National Congress) made clear that it would not tolerate any corruption charges against any of their ministers (Guha and Roy Reference Guha and Roy2013).

When similar cases affect 15% or more of the ministerial posts, we are confronted with a major adjusting reshuffle. One recent case, illustrating this type of reshuffle, occurred in Australia in March 2021, when a major reshuffle was triggered by allegations relating to rape and sexual assaults hanging over two ministers. Under the pressure of mounting public indignation, Prime Minister Scott Morrison launched a major reorganization of the cabinet that, in total, affected no fewer than eight posts. All these changes were presented by the head of government himself as a major move necessary for ‘getting the right perspective’ about justice for women and setting ‘a new benchmark, a new ambition for our government’ in terms of women's representation (Zagon Reference Zagon2021).

Finally, a ‘recasting’ reshuffle derives from the principal's will to make a change to the make-up of the cabinet for reasons that are internal to the government or the majority party/parties. Romania, for example, provides a textbook case of a minor recasting reshuffle, despite its semi-presidential system. In September 2021, Prime Minister Florin Cîțu dismissed – motu proprio – the justice minister because of a policy conflict.Footnote 9

A moderate recasting reshuffle, in turn, occurred in Denmark in May 2018, when Prime Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen picked three new ministers (accounting for 14% of the cabinet team). Although the ministers from the prime minister's party resigned voluntarily, this move was actually initiated by the party itself in preparation of the upcoming election (Reuters 2018b).

Finally, major recasting reshuffles mark the ‘infamous, earthshattering events’ in the lifetime of a cabinet, which have been observed in particular under powerful prime ministers operating at the head of a single-party government. Here, it suffices to recall Harold Macmillan's ‘Night of the Long Knives’ of 1962 in the United Kingdom (Alderman Reference Alderman1992), the major reorganization of the Spanish cabinet in late 1981 under José Calvo-Sotelo's premiership (Real-Dato and Jerez-Mir Reference Real-Dato, Jerez-Mir, Dowding and Dumont2008), or, more recently, Kyriakos Mitsotakis' sweeping reshuffle in Greece occurring early in 2021 (Reuters 2021b). That said, an event such as the single substitution in the finance ministry that occurred in Italy in 2004 also falls into this category. In this case, Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi forced the resignation of the minister Giulio Tremonti to accommodate the request by a coalition partner after serious criticisms about Tremonti's political behaviour and his technical choices (La Repubblica 2004).

Comparative patterns of cabinet reshuffles

Cabinet reshuffles in four parliamentary democracies

In this section, we proceed to apply our conceptual framework to a systematic analysis of real-world cases, intended to illustrate the viability and validity of our suggested typology.

Our investigation focuses on four West European parliamentary democracies with the largest population in 2020 (World Bank data): Germany, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom. We classify reshuffles that occurred between 2000 and 2021, using the first cabinet formed after 2000 as the first observation unit and the most recently terminated cabinet as the last for each country.Footnote 10 This choice of countries amounts to a homogenous, yet finely balanced, sample of parliamentary systems. First, inspired by the seminal work of Arend Lijphart (Reference Lijphart2012), Germany and Italy can be characterized as consensus democracies with regard to the prevalent relationships between the executive and supporting parties, which contrast with the prevailing patterns in the majoritarian systems of the United Kingdom and, if to a lesser extent, Spain. Second, we can contrast the three continental parliamentary democracies with the United Kingdom as the archetype of Westminster-style parliamentary democracy.Footnote 11 Third, these four countries display significant variations in terms of single-party and coalition government, majority and minority government, and prime ministerial powers, as well as the share of political and technocratic ministers (see Table A1 in the Online Appendix). Thus, our preliminary comparison provides a fruitful base for generating more wide-ranging hypotheses to be tested for other countries or samples of countries.

All information about personnel changes is taken from the Chiefs of State and Cabinet Members of Foreign Governments database of the US Central Intelligence Agency, while party affiliations are drawn from the WhoGov dataset (Nyrup and Bramwell Reference Nyrup and Bramwell2020). Details of reshuffle processes have been collected from online articles of widely distributed national newspapers – such as the German Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, the Italian Corriere della Sera, the Spanish El Páis and the Guardian (UK) – as well as from the Reuters website. Table 1 presents the results of this inquiry.

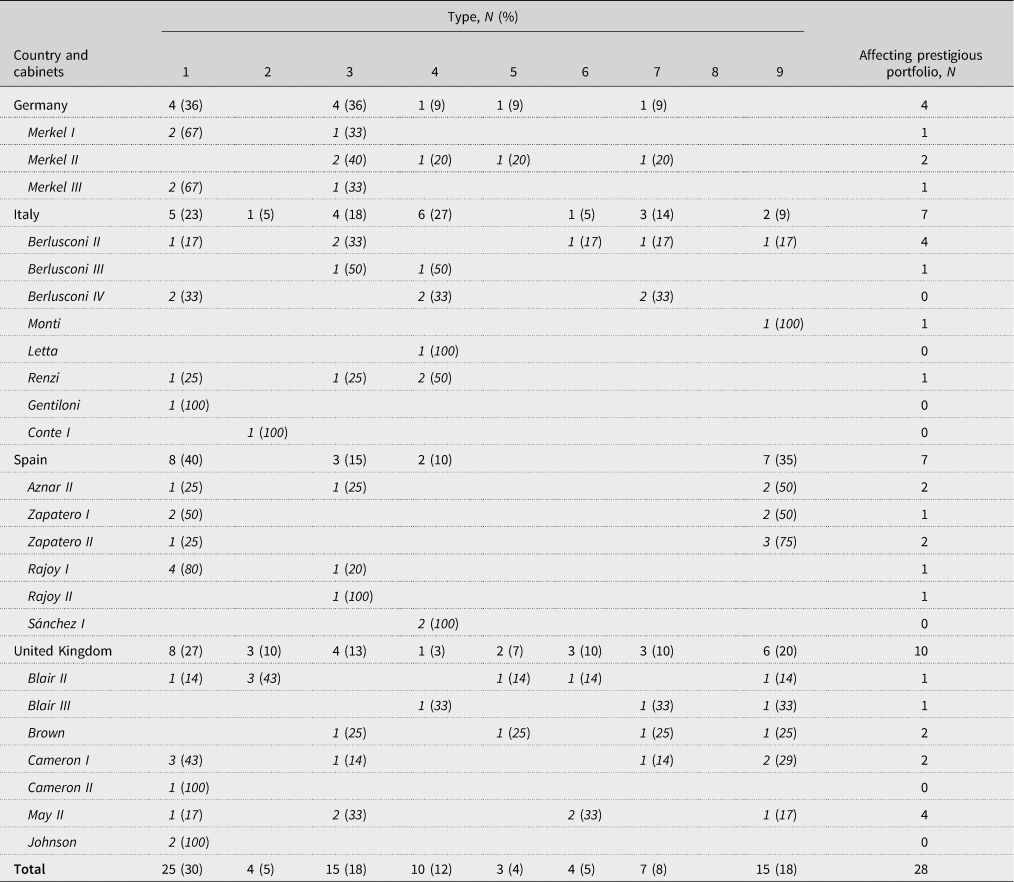

Table 1. Cabinet Reshuffles in Four West European Countries by Type

Notes: See Figure 1 for numbering of types. The calculation of the ‘scope’ is based on the number of ministerial posts at the time of cabinet inauguration; the position of deputy prime minister is not taken into consideration. The sum of rounded percentages can give totals slightly different from 100.

As Table 1 indicates, a comparison across a sample of four major West European parliamentary democracies testifies to the discriminating power of our typology, well able to accommodate cabinet reshuffles in different types of democratic regime. Moreover, we observe that, for our sample, the most common type of reshuffle is a minor adjustment of the ministerial team, following voluntary resignations. Major fixing reshuffles are the second most frequent occurrences, alongside major recasting reshuffles. However, the latter are rare in Germany and Italy, while Spain and the United Kingdom experienced 35% and 20% of such major recasting reshuffles, respectively. In terms of overall frequency, the United Kingdom is the unrivalled ‘El Dorado’ of cabinet reshuffles, with 30 episodes (featuring nearly three times as many as Germany, which experienced 11 episodes over the same period).

Principals and party changes

Though instructive, our analysis has as yet been silent about the principal of the detected reshuffles, which marks, however, no doubt an important aspect of the politics of cabinet reshuffles. Moreover, whether or not the partisan distribution of ministerial responsibilities is affected by the reshuffle does matter as well. In fact, the portfolio reallocation between parties can be used as a mechanism of interparty control (Müller and Meyer Reference Müller, Meyer, König, Tsebelis and Debus2010), to redefine public policy (Laver and Shepsle Reference Laver and Shepsle1996) or as a currency of exchange to settle cabinet conflicts (Marangoni and Vercesi Reference Marangoni, Vercesi, Conti and Marangoni2015). Political parties therefore usually have a strong interest in using cabinet reshuffles to shape different features of coalition governance.Footnote 12 The reallocation of responsibilities between parties can also result from selecting or deselecting non-partisan ministers appointed to revitalize the public credibility of the cabinet (Alexiadou et al. Reference Alexiadou, Spaniel and Gunaydin2022). This implies that even single-party governments can be subject to changes at the level of party/non-party control of cabinet departments.

For classificatory purposes, and to prove further the usefulness of our typology for comparative research, we labelled reshuffles in which the prime minister features as the principal as ‘A-type reshuffles’, and those reshuffles initiated and conducted by the political party (or parties) as ‘B-type reshuffles’. Based on our typology, both kinds of reshuffles, A and B, can be numbered from 1 to 9. Finally, we indicate partisan changes in the allocation of responsibilities with the symbol ‘ + ’. For example, in this scheme, a prime minister-led, minor fixing reshuffle without any changes in the party control of cabinet portfolios would feature as cabinet reshuffle type A1. Instead, a party-led, moderate recasting reshuffle leading to changes at the level of party control of portfolios would represent a reshuffle type B8+.

A comparison across a sample of four major West European parliamentary democracies testifies to the ability of our framework to accommodate a wide range of cabinet reshuffles in different countries (Table 2).

Table 2. Cabinet Reshuffles in Four West European Countries by Principal, Type and Party Change (Percentages)

Notes: * The figures in brackets refer to the percentage of reshuffles producing a change in the portfolio allocation among parties. A – prime minister-led reshuffles; B – party-led reshuffles. + indicates a change in the party allocation of portfolios. The sum of rounded percentages can give totals slightly different to 100. See Table A1 in the Online Appendix for the total number of reshuffles by country.

While in Germany, among the 36 theoretically possible combinations, the most frequent occurrence is a B1 reshuffle (36%), in Italy it is an A1+ reshuffle (18%). Moreover, we find that the most frequent reshuffles in Spain are those from the A1 and A9+ categories, both accounting for 25% of all reshuffles each. Similarly, in the UK the most common type of reshuffle is A1 (23%), followed by A9 (17%). Overall, the most frequent type of reshuffles are A1, A9 and A1+ (14, 10 and 8%, respectively), followed by A3, B1 (7% each), A9+ (6%), and A4, A7 and B3 (5% each). That is, more than half of all reshuffles observed are concentrated in six different categories, and one third in just three (A1, A9 and A1+). The remaining combinations occur infrequently (1% in seven cases each, 4% in four cases and 2% in three cases).

The application of our typology to other contexts and cases should allow us to draw up larger ‘landscapes of reshuffles’ that may reveal particular patterns in, for example, larger and smaller democracies, countries with different patterns of party complexion of the government, as well as divergent dynamics of change over time. However, arguably the most valuable contribution of such a typology concerns its potential to lift comparative research to the next level by relating plausible assumptions about the possible effects of cabinet reshuffles to particular types of reshuffles. The conclusion discusses some ideas emerging from our conceptual distinctions that should inform and inspire further research in this field.

Discussion and conclusion

Our analysis started from two premises: cabinet reshuffles in parliamentary democracies do matter in terms of politics and policy, and while not all reshuffles are the same, they can be conceptually differentiated and categorized. Our key ambition is to help advance future research on the politics of reshuffles and reshuffling. This includes in particular the much-contested effects of cabinet reshuffles on the fate of a government, or in fact a country as a whole. We sought to help overcome a glaring weakness of most previous research, which has tended to take each reshuffle as a unique and largely incomparable event, by developing a two-dimensional framework of types of cabinet reshuffles centring on the mode and scope of reshuffles. While we explicitly acknowledged the relevance of two other major discriminatory features of reshuffles (the nature of the principal, and changes or non-changes of party control of cabinet portfolios), we consciously ignored other possibly important aspects for the sake of keeping our typology reasonably simple and analytically manageable.

Generally, we believe that, all other things being equal, any intended effect of a cabinet reshuffle is likely to be shaped by the particular nature of the reshuffle itself – which, as we argued, can be conceptually and analytically captured by distinguishing between different types of reshuffles. We are convinced that these classificatory distinctions may come in useful when being systematically related to more particular comparative inquiries into the effects of cabinet reshuffles across time and space. Doing so should allow us to arrive at much more precise empirical hypotheses on, and assessments of, the effects that cabinet reshuffles may have. Specifically, our typological distinctions could be easily related to empirical investigations of the widely established assumptions on cabinet reshuffles as a possible instrument of prime ministerial or party leadership. In the remainder of this section, we briefly sketch out some of the more general patterns concerning different types of reshuffles and their possible effects.

To begin, the degree of the principal's activism characterizing a reshuffle is likely to make a major difference with regard to most effects. Ceteris paribus, proactive reshuffles tend to have more favourable effects for the principal, whereas most other cases in which the principal reacts to developments triggered by other players are usually about limiting the political costs of largely uncontrollable events. Conflictual ministerial resignations in particular may generate rather incalculable and politically unwelcome effects for governments and their effective principals (see also Alderman and Cross Reference Alderman and Cross1985). That said, the accomplishment of self-set strategic goals, such as pushing the government's popularity score or enhancing the principal's room for manoeuvre or its monitoring capacity, is uncertain even for the most clear-cut cases of proactive reshuffles. Just as early elections launched by the government may leave the government with a reduced or no majority at all, reshuffles (including particularly ‘vigorous’ ones) may backfire. More specifically, voters may dislike the impression of overly ‘opportunistic’ behaviour, not only regarding election timing (see Schleiter and Tavits Reference Schleiter and Tavits2018), but just as much at the level of cabinet reshuffles.

As to the scope of reshuffles, one of the first things to note is that ‘large’ reshuffles do not necessarily have the desired wide-ranging effects. Clearly focused interventions rearranging the ministerial team can have big effects on the government's political and policy performance, and the public perception thereof. Still, everything else being equal, increases in government popularity are significantly more likely to be observed after major recasting (i.e. large-scale and proactive) reshuffles (type 9).Footnote 13 These reshuffles are, by definition, designed to refresh the public image of the government and overcome perceptions of ‘immobilism’ (Alderman Reference Alderman1995: 506).

Some of the most intriguing formats of cabinet reshuffle emerge from a distinct combination of features: for example, recasting reshuffles with a relatively limited scope (types 7 and 8) are often important opportunities to improve the government's (perceived) performance, as they allow the principal to force the resignation of identified underperformers without destabilizing the cabinet's organizational set-up. Principals can use these opportunities to increase their control over ministers in complex departments and to enhance ministerial capacity (Indriðason and Kam Reference Indriðason and Kam2008). Further, proactive reshuffles are more likely to help re-establish intra-party or coalition discipline by promoting or demoting cabinet pawns and preserving general equilibria. In 1967, British Prime Minister Harold Wilson famously sacked Douglas Jay, ‘because he thought Jay was a nuisance and believed, rightly, that Jay, once sacked, would not be in a position to make trouble’ (King and Allen Reference King and Allen2010: 267). In coalition governments, recasting reshuffles of this kind are less common, but fixing and adjusting (i.e. reactive and anticipatory) reshuffles can still work as functional equivalents, as they may be used as opportunities to reallocate decision-making resources. For instance, in November 2004 the Italian Prime Minister Berlusconi – after the appointment of the minister as European Commissioner – promoted the leaders of two ‘unruly’ coalition partners, in an attempt to accommodate inter-party conflicts (Ignazi Reference Ignazi2005: 1067).

Finally, specific remodulations of public policy can often best be brought about by small reshuffles launched in response to external events that ‘legitimize’ these changes (type 4). It is no coincidence that putting pressure on a minister to resign is often used by the principal in a strategic way, seeking to remove ministers with diverging policy preferences (Fischer et al. Reference Fischer, Kaiser and Rohlfing2007). Even voluntary resignations by a single minister (type 1) can have considerable effects in terms of policy substance and political style within the department concerned, and beyond.

To conclude, this study has put forward a typology of real-world cabinet reshuffles that seeks to make explicit the major differences between individual reshuffles, even those reshuffles that may come about within the lifetime of a single government. A major contribution of our analysis is the development of distinct categories designed to capture, and inform future investigations into, similarities and variations in cabinet or ministerial turnover. Moreover, our typology provides a sufficiently fine-grained framework of reference, enabling future studies to assess the causes and effects of cabinet reshuffles in a more substantive and reliable way. Further, the suggested typology allows the development of new hypotheses about which kinds of reshuffle are more likely under certain conditions (and why), or the different effects that similar reshuffles can have, depending on third factors.

Importantly, the key distinctions suggested are compatible with other factors shaping the political fate of reshuffles, such as the timing of changes within the lifetime of a cabinet (see Kam and Indriðason Reference Kam and Indriðason2005). Indeed, the conceptually advanced comparative study of cabinet reshuffles would seem to hold a particular potential for furthering our understanding of different dimensions of ‘time’ in the study of political executives and politics more generally (see ‘t Hart Reference ‘t Hart2014: 107–112). Scholars could profit from referring to this typology also, and in particular when running systematic large-N studies across a wide variety of institutional contexts in which different types of reshuffle are the independent and political outcomes the dependent variable. Needless to say, such quantitative analyses could be meaningfully complemented by focused small-N comparisons that look into the motives, motivations and causal mechanisms emerging from the complex interplay of actors and factors. Finally, our typology can, we believe, also be trusted to provide inspiration for scholars in closely neighbouring areas of research, such as the presidentialization of political executives, party government and public policy, all of which have come to develop a growing interest in issues of cabinet reshuffles.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2022.22.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Matthew Kerby, Francesco Marangoni, and David M. Willumsen for having commented on earlier drafts of this article. Moreover, we would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers of the journal for their most valuable suggestions. Earlier drafts of this article were presented at the 2021 ECPR General Conference and the 2021 Italian Political Science Association (SISP) Conference. The usual disclaimer applies.