Populist radical right (PRR) parties have become an increasingly relevant force within the Western European electoral system over the past 30 years. They have entered governmental coalitions both nationally and subnationally and have more than tripled their share of seats in the European Parliament (Inglehart and Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2016). Does this party group have a policy effect that justifies the scale of interest in them?

Several scholars have attempted to explain how PRR parties deal with welfare benefits, in which health plays a substantial role. Most have chosen to do this by distinguishing ‘deserving’ from ‘undeserving’ citizens (van Oorschot Reference van Oorschot2006). Laurenz Ennser-Jedenastik creates a table of those ‘deserving support’ versus those ‘undeserving of support’ to explain the welfare sentiments of the PRR Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) between 1983 and 2013 (Ennser-Jedenastik Reference Ennser-Jedenastik2016: 214). In his piece on pension reforms, Alexandre Afonso explains that the ‘deservingness’ of a particular group – for example, pensioners – will save them from retrenchment (Afonso Reference Afonso2014). Alexandre Afonso and Yannis Papadopoulos focus on the Swiss case. They argue that PRR parties use the popular ordering of deservingness accepted across Europe to determine which category of recipients is ‘more deserving’ of benefits (Afonso and Papadopoulos Reference Afonso and Papadopoulos2015). However, little thought has been given to health policies as an aspect of welfare politics.

Health and, in the broader sense, social policies are integral parts of the welfare state whose importance lies in protecting and promoting its people's social and economic well-being (National Research Council 2011). Therefore, it is necessary to fill this research gap and determine the healthcare and health policy consequences of PRR parties in government. Prime examples of such consequences on the national level are the reneging of the smoking ban in Austria (Falkenbach and Heiss Reference Falkenbach, Heiss, Falkenbach and Greer2021), mixed messaging regarding vaccination in Italy, as well as minimum income laws and policies excluding certain groups from obtaining welfare benefits, of which healthcare is a direct benefit (Falkenbach Reference Falkenbach, Falkenbach and Greer2021). This is to say that there are various approaches that parties, specifically PRR parties, can take regarding health policies, but we know very little about them or the reasons they are chosen.

In his 1984 book Do Parties Make a Difference?, political scientist Richard Rose concluded that in Great Britain, forces outside the control of parties (public opinion, societal changes and economic trends) impacted policies (Rose Reference Rose1984). This conclusion was re-evaluated in a more recent literature review (Falkenbach et al. Reference Falkenbach, Bekker and Greer2019) that found that political parties and their ideologies affect health in two important ways: first, and most importantly, politics shape our health systems and establish whether a country has a national healthcare system, a social insurance system or neither (Immergut Reference Immergut1992). This means that politics frames how healthcare is thought about and approached within a society (Falkenbach and Greer Reference Falkenbach and Greer2018): is it considered a universal right available to all or is it an industry, similar to the banking, textile or electronic industries, subjected to the market with questionable regulations? Second, and as a result of the first point, political traditions affect health outcomes (Navarro Reference Navarro2008). In essence, politics informs public policy and thus affects health outcomes for a given population. It is known that social democrats tend to favour redistributive health and welfare policies, thus generally improving health outcomes. In contrast, Christian democrats and conservatives are more reserved in their redistributive policies (Huber and Stephens Reference Huber and Stephens2001). The PRR's preferences are well known, as studies combing through manifestos demonstrate (Akkerman Reference Akkerman2015); however, what policies they actually implement and enforce (specifically in the realm of health) remain sparse, especially on the subnational level.

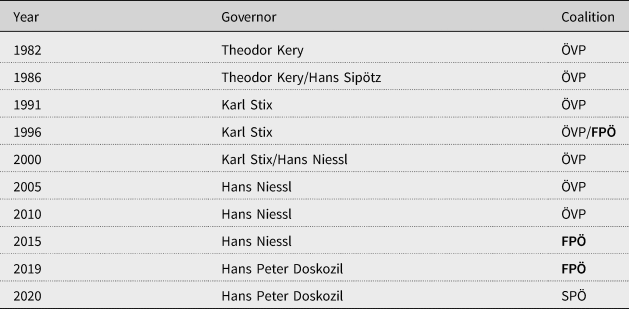

While there is an increasing list of PRR parties, only some have ever entered into government. Since the mid-1990s, PRR parties from seven Western European countries (Austria, Denmark, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway and Switzerland) have entered into a steady stream of national government coalitions (Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, De Lange and Rooduijn2016) (Table 1), most generally at the expense of centre parties (Inglehart and Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2016). Of these seven countries, two (Austria and Italy) have also seen PRR governmental coalitions form on the subnational level. Two book chapters examining the health policy impact of PRR parties in Austria and Italy on the national level (Falkenbach Reference Falkenbach, Falkenbach and Greer2021; Falkenbach and Heiss Reference Falkenbach, Heiss, Falkenbach and Greer2021) have paved the way for further research in this area. I will follow this approach to explore the health policy consequences provoked by PRR parties in Austria and Italy on a subnational level.

Table 1. PRR Parties in Western European Governments

Source: Author's own, adapted from Mudde (Reference Mudde2013).

Note: FPÖ = Austrian Freedom Party, BZÖ = Alliance for the Future of Austria, ÖVP = Austrian People's Party, DFP = Danish People's Party, DKF = Conservative People's Party, LAOS = Popular Orthodox Rally, ND = New Democracy, PASOK = Panhellenic Socialist Movement, LN = Lega Nord, L = Lega, FI = Forza Italia, CCD = Christian Democratic Centre, UDC = Union of the Centre, AN = National Alliance, PdL = People of Freedom, PVV = Party for Freedom, CDA = Christian Democratic Appeal, VVD = People's Party for Freedom and Democracy, SVP = Swiss People's Party, CVP = Christian Democratic People's Party, FDP = Freedom Democratic Party of Switzerland, SP = Social Democratic Party of Switzerland.

In order to assess the consequences of PRR parties in government at a subnational level with regards to health, I will analyse what PRR parties do in that area. I look at health policies and health system changes in the selected provinces of Austria and regions of Italy over time. Data from expert interviews with politicians and health experts as well as legal documents, media reports and historical documents inform my analysis. Details pertaining to the interviews can be found in the Online Appendix.

Theoretical framework

Generosity versus exclusivity: how do PRR parties position their health policies?

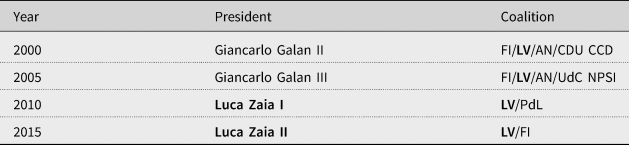

In May 2021, the first comprehensive book on PRR parties and their relationship with health policies was published (Falkenbach and Greer Reference Falkenbach and Greer2021), presenting a set of case studies that show the effects of PRR parties on health policy, thereby illuminating PRR politics. This research introduces two axes: generosity and the exclusiveness of benefits (Figure 1) as a way of thinking about the relationship that the PRR could have with welfare, and by extension, health. The generosity of benefits is well engrained within the welfare state literature (Bambra and Eikemo Reference Bambra and Eikemo2009). Conceptually, it is the extent to which people's dependence on money is reduced through increased social entitlements. In the case of health, this would imply that healthcare access be independent of a person's income (Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen and Esping-Andersen1990). When considering ways of measuring a health system's generosity, one could look towards financial barriers such as out-of-pocket expenditures or resource barriers such as capacity of intensive-care units or healthcare personnel.

Figure 1. Four-Policy Model Source: author's own.

The exclusiveness of benefits is the extent to which access to benefits is restricted based on citizenship, residency or participation in a social insurance scheme. The least exclusive benefits are available to all. The most exclusive benefits require money, legal residency or a position within the labour market. Within the realm of healthcare, this could mean the ability to afford private insurance on top of the mandatory social health insurance in countries such as Austria in order to give birth in a private hospital under the care of one's choice of doctor. In healthcare, people with money are granted everything from shorter waiting times to choosing the hospital they would like to be treated in. Within national health service systems such as Italy's, the ability to pay for extra services gives people an advantage in securing much more timely access to care.

To offer a more visual interpretation of the above, I created a four-policy model depicting the relationship between access and generosity (Figure 1).

This article hypothesizes that, when in government, the PRR will follow a liberal or welfare chauvinist approach.Footnote 1 Liberal chauvinism, which can be referred to as a combination of nationalism and neoliberalism (Kitschelt and McGann Reference Kitschelt and McGann1995), points to an economically liberal orientation, promising more accessible markets, lower taxes and less statism (Kitschelt and McGann Reference Kitschelt and McGann1995), resulting in marginal support for the collective financing of healthcare services (Greer Reference Greer2017). Ultimately, governments, or parties, following this approach to health policies are pushing for less generous healthcare benefits while simultaneously attempting to make the access to those benefits more difficult.

The other probability is that PRR parties follow a welfare chauvinist (Andersen and Bjørklund Reference Andersen and Bjørklund1990) approach to health. This approach implies that benefits are more generous due to increased health expenditure; however, access to these benefits is restricted, making them more exclusive. Today, the term is widely used by researchers (Rathgeb Reference Rathgeb2021; Rinaldi and Bekker Reference Rinaldi and Bekker2021) and similarly implies that welfare benefits should be generous (as they are in most European countries); however, these benefits should be restricted to citizens only (Cavaille and Ferwerda Reference Cavaille and Ferwerda2016). Many PRR parties have built this notion into their platform to exclude outgroups such as immigrants (Afonso Reference Afonso2014; Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt2007).

Looking more closely at the welfare chauvinist model, it is apparent that the concept of generous welfare provisions for citizens, coupled with restricted access and provisions for foreigners, directly plays into the PRR ideology of nativism. Within the literature, two different sides of this model are discussed. One focuses predominantly on the demand side of politics (voter preferences), while the other is more concentrated on the supply side of politics (party policy and ideology). The demand side stands to explain the emergence of the PRR altogether, as many voters feel that immigrants should not be immediately entitled to social benefits upon arrival (Bonal and Zollinger Reference Bonal and Zollinger2018), often identifying them as the least deserving social group (Ennser-Jedenastik Reference Ennser-Jedenastik2020). Why and to what degree voters embrace welfare chauvinistic policies and attitudes is made up of several different influencing factors: lack of viable alternatives to the traditional mainstream parties during economically uncertain times (Michel Reference Michel2017), low cultural capital (van Oorschot Reference van Oorschot2000, Reference van Oorschot2006), the previously mentioned feeling of economic inequality and cultural heterogeneity (Reeskens and van Oorschot Reference Reeskens and van Oorschot2012). In the supply-side research, scholars have highlighted welfare chauvinism as central in the policy approaches mentioned in party programmes. PRR party manifestos have been extensively researched, and it is clear that this party group favours welfare chauvinistic policies (Careja and Elmelund-Præstekær Reference Careja and Elmelund-Præstekær2016; Heinisch and Werner Reference Heinisch and Werner2019).

However, what is not entirely clear is whether there are distinct circumstances that must be in place for PRR parties to favour one approach over the other. What also remains unclear from this literature is whether a given welfare approach also applies to PRR parties' health policy choices. This article seeks to use and build on these theories to explore whether PRR parties' health policies or attitudes towards health follow the approaches previously mentioned. In order to accomplish this, knowing when PRR parties are able to shape policy can be particularly helpful.

Political constraints: when can PRR parties shape policy?

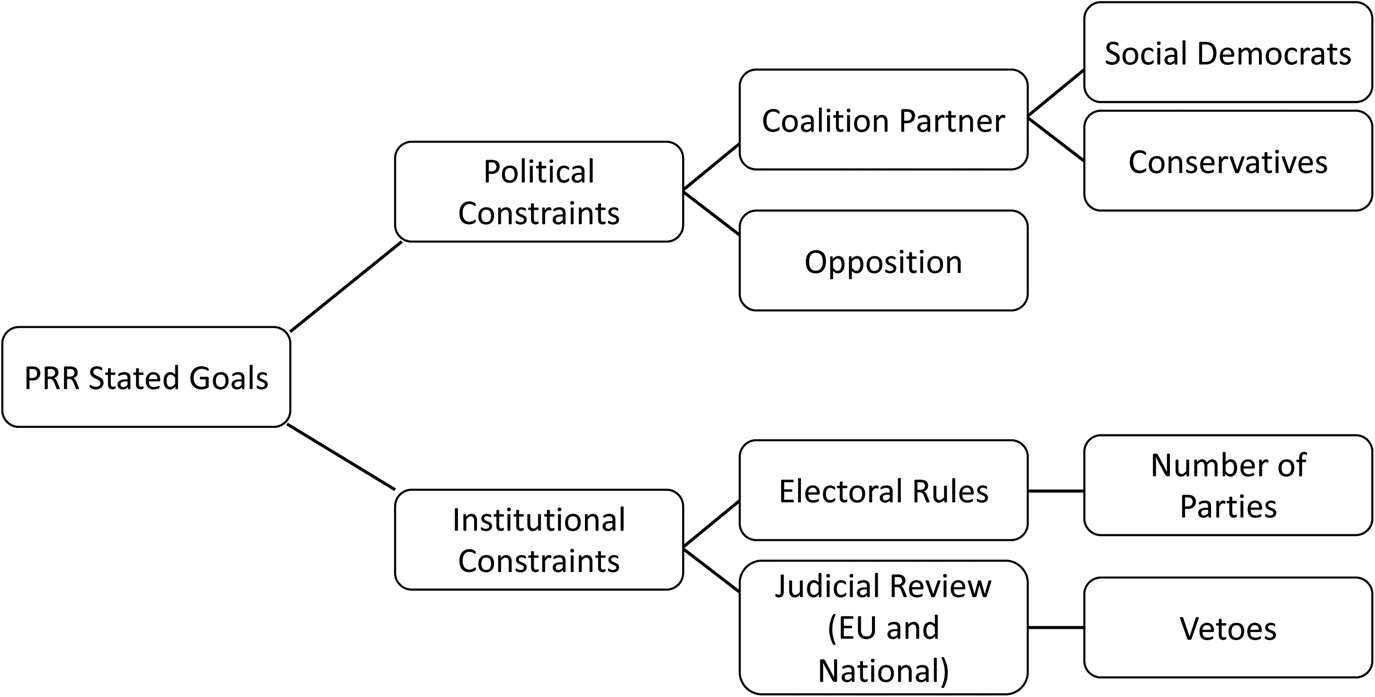

Many factors influence the impact of a political party on policy (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Impact of the PRR on Policy Source: adapted from Falkenbach and Greer (Reference Falkenbach and Greer2018).

Based on and expanded from the study by Michelle Falkenbach and Scott Greer (Reference Falkenbach and Greer2018), there are many political and institutional constraints on the PRR party. Electoral rules determine the effective number of parties in a party system. The higher the number of parties in any one government, the less strength any one party has, in general. Furthermore, when a given party system has many parties, governments typically require coalitions. In Western Europe, most PRR parties have formed coalition governments with established conservative, mostly Christian democratic, parties (the exception is Italy).Footnote 2 In a coalition government, PRR parties are constrained by the coalition agreement and the partner party. In addition, the colour of the coalition partner matters greatly in terms of health policy outcomes. For example, on the national level in Austria, the FPÖ was only ever in government with the conservative Austrian People's Party (ÖVP), a party that is not known for making health policies. Thus, in such a case, the likelihood that a PRR party controls the health sector is high, allowing it to affect health policy significantly. On the other hand, as this article will demonstrate, if the PRR party is in a coalition with a social democratic party, known for being actively involved and making health policies, the PRR party's influence on health will be minimal.

The second major external constraint is the rule of law (Falkenbach and Greer Reference Falkenbach and Greer2018). In particular, the constitutional judicial review, but also the administrative public law review and international laws such as those of the European Union, constrain the types of policies that PRR parties wish to pass. It is often the case that proposed PRR legislations are overturned because they are unconstitutional or breach fundamental human rights (Albertazzi and Mueller Reference Albertazzi and Mueller2013). If a country has strong, established institutions, independent courts and an engaged civil society, PRR policies that can be classified as being directly welfare chauvinistic are generally deemed unconstitutional in some way, shape or form.

In summary, I expect PRR parties in subnational governments to pursue welfare chauvinistic policies regarding healthcare. While they might not always be able to pass such policies due to the constraints depicted in Figure 2, I expect them to push in this direction. In the subnational case, I expect that coalition politics will matter the most in determining how much power a PRR party has with regard to health. When in coalition with a Christian democratic party, the PRR's influence on health will likely be greater. Its ability to follow either a welfare or liberal chauvinist approach will be more plausible given that Christian democrats are typically less interested in health policies. When in coalition with a social democratic party, I expect the PRR party to have a minimal influence on health as that competency would likely be assumed by the social democratic party, leaving the PRR party in charge of immigration, integration and security policies.

Research design

Case selection

Austria and Italy are two countries with a particularly long history of PRR parties in government both nationally and subnationally.Footnote 3 In addition, the FPÖ in Austria and Lega in Italy are close allies within the nationalist groups in Europe (Balmer Reference Balmer2020); they are also among the oldest, most stable and most established cases of the PRR party family in Europe and can be seen as prime examples of the right-wing populism that is predominant in contemporary Europe (Plescia et al. Reference Plescia, Kritzinger and De Sio2019).

While examining the cases of Austria and Italy on a national level is valuable, going subnationally gives me additional leverage that a country-level analysis cannot provide. Advantages of subnational comparative analysis can also be found in substance, theory and methods. Substantively, subnational research allows for the creation of new theories, specifically ‘when subnational observations cannot be explained by national-level theories’ (Giraudy et al. Reference Giraudy, Moncada and Snyder2019: 5). Methodologically, I am able to increase my case count as there are many more observations.

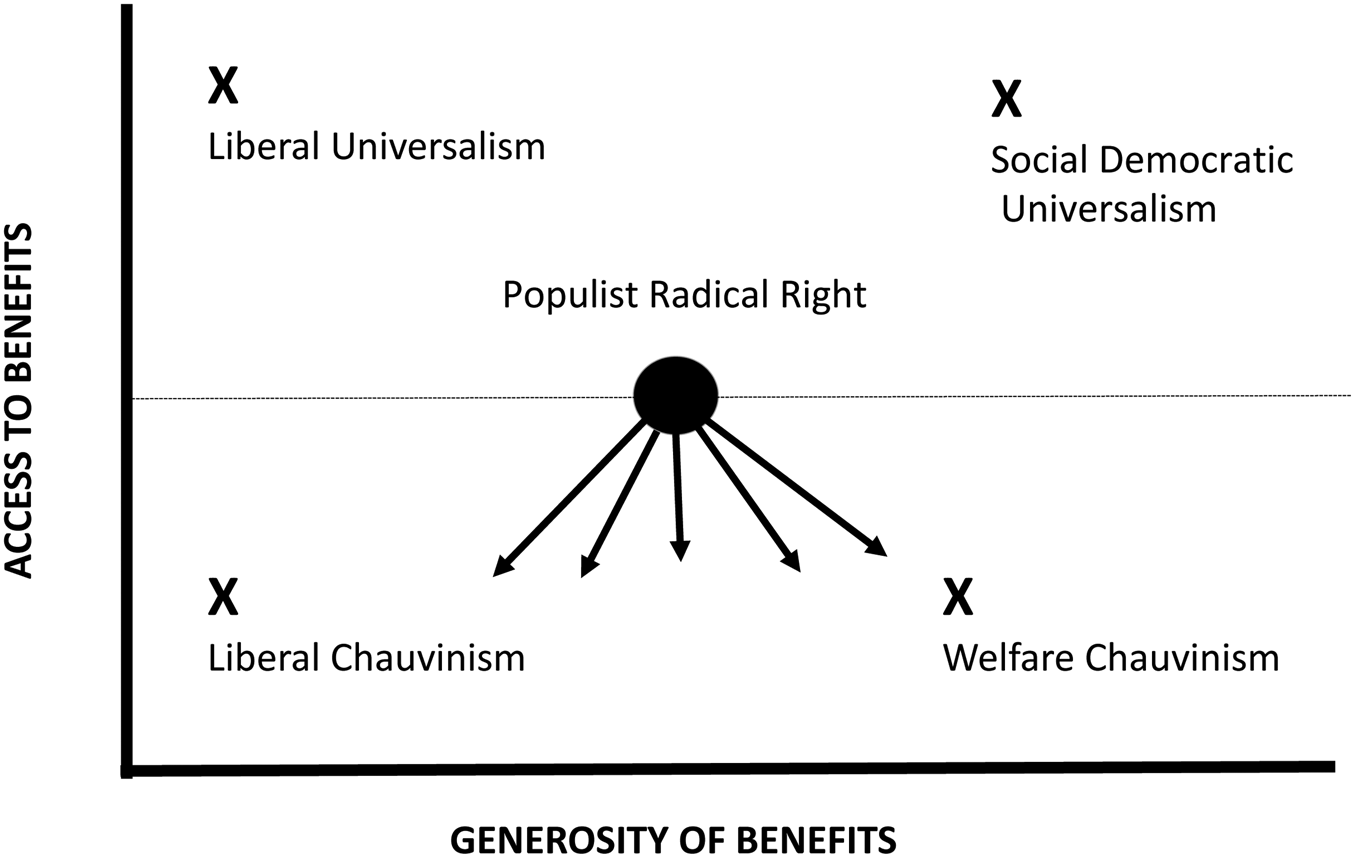

To understand what approaches to healthcare and health policies PRR parties take when in government on a subnational level, I compare four subnational cases: two provinces in Austria (Carinthia and Burgenland) and two regions in Italy (Lombardy and Veneto). The two provinces in Austria were selected because they had a PRR governor or vice governor and held at least one other ministerial position over a period of time. The reason for this specific criterion was that if a PRR party held either the governorship or the vice governorship along with at least one other ministry, one could expect the party to have an increased influence on policy due to its more pronounced involvement. The case selection for Italy was first narrowed down to the north as it is the macro-region in which the PRR Lega first developed, and its healthcare system is more comparable to its northern neighbours (Ferré et al. Reference Ferré, de Belvis and Valerio2014). The regions of Veneto and Lombardy were ultimately chosen as they are both considered Lega strongholds (Cento Bull Reference Cento Bull2009) and because the Lega has consistently been in government since the 1990s. There has been a Lega governor in Veneto since 2010 and in Lombardy since 2013, thus allowing me to maximize the odds of finding a Lega impact that is unconstrained by a coalition partner. This is essential because the goal of my study is to analyse the impact of the PRR, and coalition partners can prevent PRR parties enacting their preferred policies.

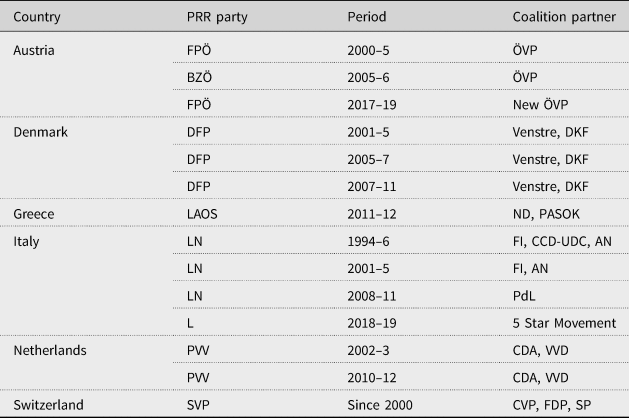

Regarding time periods, in Carinthia, the focus will be on 1999–2013 because the FPÖ held the governorship as well as at least one other ministry (Table 2), while in Burgenland the focus will be on 2015–20 since that is when the FPÖ held the vice-governorship and at least one another ministry in the provincial government (Table 3). In both Lombardy and Veneto, I will look at all the years starting from 2000 since the Lega was heavily involved in government over the last 21 years and held the presidency in Lombardy from 2013 onwards (Table 4) and in Veneto from 2010 onwards (Table 5).

Table 2. Case Selection: Carinthia

Notes: SPÖ = Social Democratic Party of Austria, ÖVP (until 2018) = Austrian People's Party, ÖVP new = New Austrian People's Party, FPÖ = Freedom Party of Austria, BZÖ = Alliance for the Future of Austria, Green = Green Alternative, TS = Team Stronach. Names in bold are PRR parties.

Table 4. Case Selection: Lombardy

Notes: FI = Forza Italia, LN = Lega Nord, AN = National Alliance, CDU = United Christian Democrats, CCD = Christian Democratic Centre, UdC = Union of the Centre, PdL = People of Freedom, FdI = Brothers of Italy, LV = Venetian League – Lega Nord, NPSI = New Italian Socialist Party, L = Lega. Names in bold are PRR parties.

Data and methods

To assess the PRR's impact on health policy, I conducted over 35 semi-structured interviews between 2016 and 2020 with political actors, researchers, health professionals and policy experts in the two countries and the respective relevant regions. The interviews were conducted in an iterative process. Cold emails, professional social media sites (researchgate, LinkedIn), word of mouth and conferences were used to establish contact and schedule interviews. Because this research fell under the International Review Board (IRB) exempt category two, recording of the subjects was possible as there was only minimal risk to the subjects. Therefore, all interviews were recorded and transcribed. Document and interview coding occurred in an iterative process using the software MAXQDA, a qualitative software package for qualitative data organization and analysis.

I also collected archival documents at national and regional/provincial levels to provide an institutional context behind the policy decisions. This body of text includes laws and regulations passed at the regional/provincial levels on relevant policies such as failed hospital mergers or the evolution of the healthcare system in Lombardy. I visited each regional and provincial website to determine if any relevant health policies were passed during my time of study. The analysis of legal and historical documents has built the framework for the comparative analysis of the subnational provinces and regions in both countries and supplements as well as complements the interviews, giving a holistic and thorough picture of the PRR's impact on health policies.

Findings

What are the health consequences of the FPÖ in subnational governments?

Healthcare in Austria

Austria is a federal, parliamentary, representative democratic republic composed of nine provinces. The health system was created based on the Bismarckian social insurance principle and is financed by wages. Two elements play a significant role within the health system: the social insurance funds and the hospitals. Health insurance funds attain their revenue through employee and employer contributions, meaning that the provinces have a financial connection to the social insurance funds; however, they have limited control over them (Obinger Reference Obinger, Castles, Obinger and Leibfried2005).

Most social policy fields, health included, fall within the legislative competencies of the national government (Article 10, 12 B-VG). However, everything surrounding hospital care (structural policies, the planning of inpatient care), health promotion and prevention services as well as the enforcement of legislation are competencies that fall to the nine provinces. Put differently, the national government is responsible for setting up the framework legislation while the provinces are responsible for the more detailed legislation, implementation and guaranteed hospital care within each province (Mätzke and Stöger Reference Mätzke, Stöger, Fierlbeck and Palley2015).

The case of Carinthia

Austria's southernmost province was dominated by the FPÖ under the charismatic leadership of Jörg Haider for close to 13 years.Footnote 4 Unlike the social democrats that had previously dominated the province's political landscape, Haider was able to pick up on and use globalization to his advantage. He realized that there were groups unable to cope with these extreme transitions – political science terms these people the ‘modernization losers’ (Luther Reference Luther, Merkl and Weinberg2003) – the introduction of computers, the opening of borders and the development of the European Union (Interviewee 1.2, political scientist). Throughout the 1990s, many people, particularly those less educated, felt increasingly threatened by immigrants and generally feared being left behind (Quinones Reference Quinones2017). Those were precisely the type of people that Haider was able to get on his side. He led an aggressive populist-style campaign throughout the 1990s, stressing issues such as political corruption, ‘over-foreignization’ and immigrant criminality and the values of the ‘little man’ to win over these voters (Luther Reference Luther, Merkl and Weinberg2003). This was the beginning of the shift of the working-class people from the Social Democratic Party of Austria (SPÖ) to the FPÖ.

In the specific case of health, there was a long-standing tradition that the social democrats dominated the health portfolio both nationally and subnationally. The reason for this is that ‘the SPÖ had the most pronounced health political ideas and also the greatest acceptance amongst the population in this area’ (Interviewee 1.5, politician). Thus, it comes as no surprise that in Carinthia, the reds (SPÖ) were always given the health portfolio.

However, there were a few things the FPÖ did do within the Carinthian health sector. First, Haider introduced many structural reforms as he knew that only by changing the structures would he get his people, the FPÖ, into positions of power generally held by the SPÖ. ‘This is something that Haider was exceptionally good at: combining departments, changing them, or splitting them and thus being able to place new people in positions of power’ (Interviewee 1.2, political scientist). One of these structural reforms led to the FPÖ's ‘domination of the KABEG, Carinthia's hospital management company supervisory board. This move limited the competencies of the SPÖ health adviser’ (Interviewee 1.5, politician).Footnote 5 With the advisory board of the hospital management company under its belt, the FPÖ, in accordance with the ÖVP, sought to reduce or eliminate the influence of the provincial government on the provincially owned hospital infrastructures. The goal was privatization wherein ‘the FPÖ and ÖVP worked together to turn these structures into self-made companies so that the political influence, which was primarily present through the SPÖ, could be reduced’ (Interviewee 1.2, political scientist).

The FPÖ not only wanted to dominate advisory boards within the healthcare sector to reduce the SPÖ's influence, but it also wanted to decrease bureaucratic structures within hospitals. This was significant as ‘a not so small portion of the provincial budget’ was dedicated to the hospital infrastructure in the province (Interviewee 1.4, politician). This meant that by keeping hospital administrations thin and by dominating the advisory boards, the FPÖ could redistribute funds allocated to hospitals and use them elsewhere.

In fact, during Haider's second term, 2000–5, ‘the FPÖ wanted to close several regional hospitals and medical institutions to save money. They produced studies that would have led to clear cuts’ (Interviewee 1.4, politician). The SPÖ, in charge of the province's health department, argued that there was no question that savings needed to be made; however, these savings should be acquired through a better-suited work distribution of the regional hospitals and a better endowment of the central hospitals, the Klinikum Klagenfurt and Villach, and not through the closure of any hospitals. The SPÖ had also argued that ‘closing these hospitals would have had major consequences as the regional hospital and medical institutions were important employers and built up important social structures’ (Interviewee 1.4, politician). The SPÖ easily deflected deals involving healthcare because it could be proved that such takeovers – privatization – would never have been beneficial to the patients.

The general problem with the FPÖ and health was that ‘they did not have an identified health programme’ (Interviewee 1.5, politician) or plan, which is why the SPÖ continued to dominate the health sector despite the FPÖ's attempts to ‘disempower the health adviser and force through their privatization plans’ (Interviewee 1.4, politician). What made the FPÖ so dangerous when it came to health was ‘their vulnerability to proposals where the quality of health services were promised to be upheld, but money could be saved by sliming bureaucratic structures’ (Interviewee 1.4, politician). German companies wanted to take over Carinthian hospitals time and time again, and the FPÖ was easily persuaded by this as promises of increased savings were made. A prime example of such a case was:

When the FPÖ appointed a certain Ms Manegold from Germany as KABEG supervisor in 2010. She worked very closely with the FPÖ health speaker Kurt Scheuch. The relationship between the two resulted in several lawsuits, Manegold's dismissal, and most importantly, a very weak and inconsistent regional structural plan for health that lacked implementation due to the political opportunism practised by the FPÖ. (Interviewee 1.5, politician)

A non-contested position was reached on the point of healthcare between all involved parties, and the SPÖ resumed complete control of the health advisory position without the interference of the FPÖ.

Despite the FPÖ's questionable involvement in specific health (primarily hospital) projects, ‘to give Haider (or the FPÖ) any profile relating to health would be presumptuous. The health sector and the employee representation sector are two things that Haider generally didn't touch; he mostly left these to the SPÖ’ (Interviewee 1.3, politician). This meant that decisions such as prevention strategies, ensuring public health services and implementing the federally regulated decisions generally fell into the hands of the SPÖ. The FPÖ, for its part, favoured structural and administrative minimalism and privatization so that it could use the generous budget given to hospitals for other priorities. The surplus budget was used by the FPÖ to ‘take care of their own, while successfully shutting out the rest. They tried to do this using as few resources as possible (in, for example, the healthcare sector) to be able to “buy” political success’ (Interviewee 1.4, politician) in other areas, thereby following a more liberal chauvinist approach to healthcare while simultaneously following a welfare chauvinist approach in other sectors.

The maintenance and survival of the healthcare sector in Carinthia can be attributed to the strength of the SPÖ, as without its years of experience, diligence and conscientiousness, many hospitals would have been closed. It also saved the province from sell-outs to Germany, which would have left the healthcare budget severely strained, the unemployment rate higher than necessary and a very likely scenario of a two-tiered hospital system.

The findings in the case of the FPÖ and Carinthian health policies come down to one main point: avoid the health sector and leave it in the hands of the SPÖ unless money can be deflected into other sectors, thereby upholding the ‘Carinthia first’ mentality.

The case of Burgenland

Located in the country's easternmost corner, Burgenland is not only the region with the country's smallest population (293,433) but also the youngest addition to the country of Austria (1921 (News.at 2005)). Switching between Christian democrat (ÖVP)- and social democrat (SPÖ)-led governments after its initial founding, Burgenland settled on a steady line of SPÖ governors, starting in 1965 with the ÖVP as its coalition partner. In 2016, this dynamic changed. The SPÖ still had the majority in the province but chose to form a coalition with the FPÖ. While this decision caused outrage among the federal SPÖ party, the cooperation mainly worked in favour of the provincial SPÖ for two reasons. In holding a governmental role, the FPÖ's criticism of the government significantly decreased as it was no longer in opposition, and its political support in the region decreased as it was given less significant roles within the regional administration and thus had less opportunity to claim credit for achievements important to its followers. These occurrences, coupled with the region's general makeup, took the wind out of the FPÖ's short-lived sails, making it an essentially uninfluential party in the governmental history of the province.

The FPÖ did not have nearly as much electoral success in Burgenland as it did in Carinthia. By 1987 the party reached over 5% in the parliamentary elections (7.31%) and slowly began growing, making itself known as an opposition party that was not afraid to criticize the SPÖ/ÖVP provincial government. Although the FPÖ had a short stint in the 1996 SPÖ/ÖVP coalition government, the FPÖ was clearly the junior party and was only given one portfolio, while the other two parties received three portfolios apiece, including the governorship and vice-governorship.

The FPÖ in Burgenland always had the lowest provincial parliament election results. Why? Burgenland was, for longer than in other regions, made up of predominately blue-collar workers. You can probably count on two hands the amount of industrial business there is, and 97% of all businesses are small or medium-sized. So, here the SPÖ found a population structure that more or less meshed well with their programme as elsewhere. Another point – the small structure of the province. It is very accessible, meaning that politicians here can be everywhere and have this closeness with the people that is often hard to establish elsewhere. It doesn't matter if they are promoting a new fire truck; if it's a sports match, something cultural, 300,000 inhabitants have the possibility to be in contact with politicians in a very uncomplicated way. (Interviewee 1.8, politician)

The SPÖ was able to keep a closeness with the citizens over the years, and by being a more established and bigger party, it left no room for the FPÖ to expand in the political arena.

By the 2015 elections, the migration crisis was in full swing and the FPÖ, both nationally and subnationally, used this to its advantage. Slogans such as ‘The flood of asylum seekers is rising unchecked!’ or ‘Did you know that you will become a stranger in your own country?’ (Hengst Reference Hengst2015) filled campaign posters and speeches, creating uncertainty in the country and the province. Not surprisingly, the FPÖ profited electorally from this, gaining 6%, putting it at 15.04%. Although the FPÖ was still in third place in the overall election results, Governor Hans Niessl (SPÖ), entering his fourth term, noticed the growing strength of the FPÖ and decided to join forces with it.

The FPÖ was given two roles in Niessl's fourth government (2015–19): FPÖ party head Johann Tschürtz became deputy governor and was in charge of the security portfolio, and Alexander Petschnig (FPÖ) was given the portfolio of tourism and economy; all the other portfolios, including health, stayed in the hands of the SPÖ.

While it seemed as if the FPÖ played a relatively insignificant role in the Niessl government, its hard line on immigration began influencing the SPÖ governor. In 2016, Niessl told the media that ‘in areas where unemployment is particularly high, the free movement of people must be restricted, for example in construction and related trades’, which gained him prompt support from his coalition partner Petschnig (FPÖ), who added, ‘Given the drama of the situation [referencing the migration waves], a sectoral closure of the labour market is the order of the day’ (Orovits Reference Orovits2016). Interestingly, both the SPÖ and the FPÖ were only speaking about the construction industry and not the tourism industry, since foreigners made up 54% of the tourist industry in Burgenland, whereas construction ‘only’ counted for 35% (Orovits Reference Orovits2016). Looking at the other industries, agriculture has 74% foreign workers in the province and healthcare workers, specifically carers, are mostly ‘independent’, self-employed, female, foreign nurses who are placed through agencies (Kuhlmann et al. Reference Kuhlmann2020).

As to actual accomplishments, the FPÖ Burgenland party head, Géza Molnár, stated in an interview, ‘we put an end to the debt policy, there are more jobs, more employers and the tourism numbers are better than ever, and we made Burgenland safer’ (Tscheinig Reference Tscheinig2019). In addition, the FPÖ claimed that the coalition did not argue – as was previously common under the SPÖ/ÖVP – but instead worked together in a very solution-oriented, trusting partnership. The FPÖ managed to stay in government with two portfolios (safety and the economy as well as tourism) from 2015 until 2020, after which the new governor Hans-Peter Doskozil (SPÖ) won the absolute majority and did not need a coalition partner.

The case of Burgenland shows how other parties can reduce the policy and political influence of the FPÖ. By forming a coalition with their most critical opposition party, the SPÖ managed to silence the FPÖ, thereby decreasing its power and influence. In addition to this strategy, the SPÖ in Burgenland also adopted the FPÖ's anti-immigrant stance. This welfare chauvinist approach coupled with its own position on welfare expansion allowed the SPÖ to win the absolute majority in the province and dispose of its PRR partner. This case demonstrates that a PRR party can, in fact, be defeated and that mainstream parties' adoption of some PRR policies (such as a harder stance on migration) can help in elections.

What are the healthcare consequences of the Lega in subnational government?

Healthcare in Italy

The Italian state is a parliamentary, democratic republic with a multiparty political system wherein parliament and the prime minister have more authority than the president. The Italian healthcare system has a mixed public–private system of provision, wherein healthcare is provided by the regionalized tax-based Italian national health service (Servizio Sanitario Nazionale – SSN), following the Beveridge model of healthcare. Since the early 1990s, every regional government has created its own healthcare system. Each region, not the national government, is solely responsible for creating, organizing and financing its regional healthcare system (RHS) (Perna Reference Perna2018). At the national level, the Ministry of Health determines the overall budget for the SSN. Funds are allocated according to a complex formula based on population size, average age, mortality rates and other regional characteristics, such as spending levels.

Since health competencies have been devolved to the regions, the goal is to identify how the Lega in Veneto and Lombardy impacted health policy and the healthcare system in a broader sense. While in Austria the SPÖ was typically in charge of the health portfolio, in Italy, the centre-right Forza Italia (FI) initially dominated the health portfolios in Lombardy and Veneto.

The case of Lombardy

The region of Lombardy is located in the far north of the country, surrounded by the regions Trentino-Alto Adige and Veneto on the east and Piedmont on the west. With the Italian healthcare reform in the 1990s (Decrees 502/92 and 517/93) – when the national government decided to decentralize healthcare, leaving it up to the regions how they wanted to spend public money – Lombardy, at that time under the leadership of Roberto Formigoni (FI), took a different route from the other regions. While most regions continued to use the central government's reimbursement rates and quality standards, Lombardy passed Regional Law 31/1997 and set up a quasi-market model (Brenna Reference Brenna2011).

The difference between the Lombard model and perhaps the more traditional healthcare models adopted in central Italy concern freedom of choice:

From the patients' point of view, the difference between, for example, the regional Emilia Romagna model and the Lombardy model is the freedom of choice. So, in Lombardy, they pay the same, but they have a wider freedom of choice as they can choose freely between public and private providers. There were no differences in terms of the rights the service provided and even the waiting times. (Interviewee 2.5, public health expert)

While there might have been advantages in a hospital-centric system in the early 1990s, it seems that the disadvantages of such a system began increasingly apparent over time – culminating with the COVID-19 pandemic.

It is important to mention Roberto Formigoni (FI), president of the region from 1995 until 2013, even though he does not belong to the Lega party. According to Cristiano Gori (Reference Gori and Gori2010), Formigoni and thus the FI, along with the regional health council, was responsible for implementing the Lombard regional health model (described above). This very hospital-centric model considered ‘general practitioners [GPs] useless under Formigoni and even under the Lega’ (Interviewee 2.17, economic sociologist and social policy expert). Formigoni adopted this new model based on the subsidiary principle. Not only did Formigoni and FI as a whole play an essential role in this transformation, but Catholic interest (such as Comunione e Liberazione) and business groups were also brought on board to solidify the quasi-market model. What is important to understand is that:

The president of Lombardy for almost 20 years, Formigoni, came directly from its [Comunione e Liberazione] ranks. So, what Formigoni did for 20 years was practically occupy the healthcare system in Lombardy. So, it means that every time they had to replace someone like … I don't know … the head of surgery department or whatever, they tried as much as they could to put their own people in, people loyal to the traditional Catholic Church. (Interviewee 2.17, economic sociologist and social policy expert)

The involvement of the Catholic Church in the Lombard healthcare system made it even more unique. For example, in Lombardy, ‘you could not become, or you were not able to become, a doctor in gynaecology if you were not supported by the Catholics’, and it was challenging at the time to ‘use your right of abortion because most doctors did not allow it’ (Interviewee 2.17, economic sociologist and social policy expert). Furthermore,

They [the Formigoni government] opted for a very different framework, where the private sector had the upper hand over the public. San Raffaele Hospital, San Donato Hospital. If you look at the name, all the hospitals, all the private hospital in Italy, are named after a saint: San Donato, San Raffaele, because the majority of the hospitals in Italy were originally founded by the Catholic Church. (Interviewee 2.6, medical and public health expert)

During the Formigoni presidency (1995–2013), welfare (specifically health) was also heavily associated with the freedom of choice and the will of the market (Pavolini Reference Pavolini2008). In addition, ‘the provision of health services, both in hospital and in the community setting, depended solely on hospitals’ (Interviewee 2.18, medical professional and public health expert), implying that the system was hospital-centric. This association did not change when the Lega took over the presidency in 2013. Although Roberto Maroni (Lega, 2013–18) recognized and attempted to change the system's imbalances, he, as well as his successor Attilio Fontana (Lega, 2018–present), were unable to change the existing market-based model.

Starting in 2005, with Alessandro Cè's (Lega) appointment as councillor of health, the Lega almost constantly controlled the regional health department (Vampa Reference Vampa and Vampa2016), thereby marking the Lega's increasing strength as a coalition partner in the centre-right Formigoni government. However, because Formigoni played such a decisive role within the health sector, Cè's opinions mattered little and were ‘practically crushed by Formigoni’ (Interviewee 2.17, economic sociologist and social policy expert). Heart surgeon Luciano Bresciani (Lega) replaced Cè in the autumn of 2007. In 2012, Bresciani stepped down after a fraud investigation (involving President Formigoni) regarding bribes paid to a medical supply company (Milano Today 2014). These accusations also led to the resignation of Formigoni, who was replaced by Roberto Maroni (Lega) in 2013. In sum, the Lega's role in healthcare at this time was essentially appeasing Formigoni’s neoliberal quest to privatize healthcare. Despite holding important positions (such as health councillor), the Lega was powerless against Formigoni and the FI structures.

When Maroni took over the presidency, two critical changes in healthcare were made. In 2015, Law 23/2015 promised to enhance the social welfare aspect of the healthcare model by increasing support for community welfare. It also sought to rebuild the local structure of governance to decrease institutional fragmentation. In essence, the goal was to centralize the region in certain aspects.

The second change occurred when the Maroni government introduced a new ‘autonomous income’ (reddito di autonomia) in 2015, which was explicitly created to support the more disadvantaged sectors of society (such as unemployed, elderly and disabled people) (Vampa Reference Vampa and Vampa2016). The central government strongly criticized this law (Senato della Repubblica 2017) as it claimed that with Resolutions X/5117 and X/6164, Lombardy was completely modifying healthcare, thereby replacing some of the founding pillars of the Health Reform Law 833 of 1978. The fear was that the new autonomous income was attempting to privatize public care for the chronically ill (Senato della Repubblica 2017).

A final point of action worth mentioning is that Maroni threatened to cut regional transfers to municipalities that hosted refugees (Vampa Reference Vampa and Vampa2016). In an open letter to the municipalities, Maroni stated the following:

I decided to write a letter to the prefects to warn them about bringing new illegal immigrants here to Lombardy. I also decided to write to the mayors to tell them to refuse to take them. If mayors accept them, we will reduce regional transfers as a disincentive because they do not have to. Whoever accepts illegal immigrants is violating the law and will suffer this consequence (la Repubblica 2015).

These words were supported by the president of Veneto, Luca Zaia (Lega), who backed Maroni, stating, ‘we are mad at the inadequate government that, in official documents, invites us to manage the “acute phase” of immigration. When we all know that it is not acute, it is chronic’ (la Repubblica 2015). While it was not officially stated, one can assume that both presidents rejected supporting the new immigrants due to financial reasons and nativist sentiments. In 2018, Attilo Fontana (Lega) took over the presidency, and his legacy will likely revolve around how poorly he and his minister of health initially managed the COVID-19 pandemic.

In summary, Lombardy was heavily influenced by Formigoni, the FI party and the Catholic movement Comunione e Liberazione, making it difficult for the Lega to create its own health agenda when it took control of the region in 2013. What did become apparent through the changes that the Lega was able to make in Lombardy is that it followed, whether willingly or not, the liberal chauvinist path that the FI set out. In addition, the Lega attempted to centralize power in the region and began threatening mayors who wanted to bring illegal immigrants into their municipalities. Whether this can be interpreted as being partial to a more welfare chauvinist approach to health and social benefits remains unclear.

The case of Veneto

The Veneto region is located in the north-eastern quadrant of Italy. To the east, it is bordered by Friuli-Venezia Giulia and the Adriatic Sea, and to the west, it borders Trentino-Alto Adige and Lombardy. Veneto's southern border is shared with Emilia-Romagna. Veneto follows the Aree Vaste model of healthcare. The only difference between this model and the classic Italian healthcare model is that there is an extra level of bureaucracy between the regional government and the local health units (azienda sanitaria locale – ASL).

Unlike the Lombard system, the Venetian healthcare model is characterized by ‘a strong orientation towards meeting the needs of individuals as well as the community through the integration of health and social services’ (WHO 2016: 16). This becomes apparent when one looks at where the power to make healthcare decisions lies:

In Veneto, I think regional bureaucracy is still very strong. But I mean, regional power is strong, but the power is probably more distributed, between the regional bureaucracy and local managers. In Lombardy, on the other hand, local mayors have no influence on healthcare. While certainly in Veneto, they have some influence, to a certain extent. (Interviewee 2.21, economic sociologist and social policy expert)

While decision-making power in Lombardy is strictly regionally based with regards to healthcare, in Veneto, decisions are more devolved, fitting nicely with the community-based model and the integration of services. Also, contrary to the Lombard model, primary care plays a central role in the Venetian system. Thus, it is not surprising that the GP is the first contact point for patients and central to the Venetian healthcare system.

Unlike President Formigoni in Lombardy, President Giancarlo Galan (FI, 1995–2010) did not come from the Catholic faction of FI, ‘he did not come from this specific movement called the Comunione e Liberazione’ (Interviewee 2.21, economic sociologist and social policy expert). Thus, when it became time to decide what kind of healthcare system the region should implement, he opted for ‘a more traditional system, placing much more importance on outpatient care and public services. So, in some ways Veneto, the organization of the healthcare system is more similar to Emilia-Romagna and Tuscany, so the red, social democratic, regions’ (Interviewee 2.21, economic sociologist and social policy expert).

Luca Zaia (Lega) became president of the region in 2010. He and his regional council, led by Health Minister Luca Coletto (Lega), supported Galan's system. They ‘followed this traditional path’ (Interviewee 2.21, economic sociologist and social policy expert), making no efforts to change it into something more market-oriented. In fact, ‘I don't expect privatization, I expect that they keep on investing in public healthcare. My impression in Veneto was that the League was just keen on organizing the system, not transforming it’ (Interviewee 2.17, economic sociologist and social policy expert).

In 2012, the Zaia government implemented a regional planning legislation (Regional Law 23/2012) that made the system even more patient-oriented by placing the person at the healthcare system's centre (Ghiotto et al. Reference Ghiotto2018). Four years later, in 2016, the government passed Regional Law 19/2016, defining a new primary care model in which integrated medical groups were promoted. The idea that ‘Veneto is a lot closer to central Italy’ regarding healthcare was confirmed with this change. Unlike in Lombardy, where GPs were seen as useless, Veneto praised GPs as being ‘an important part of the network, of the care network’ (Interviewee 2.17, economic sociologist and social policy expert). These changes solidified the patient- and community-oriented nature of the Venetian system and proved to be very beneficial during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In summary, under the leadership first of President Galan (FI) and then President Zaia (Lega), Veneto followed a very community-based approach to healthcare with little to no privatization. While both these approaches to healthcare found more similarities with social democratic parties' health policies, it is unclear what role the Lega's nationalistic sentiments will play into the health system design and health policies in the future (recall the quotation regarding migrants in the previous section).

Discussion and conclusion

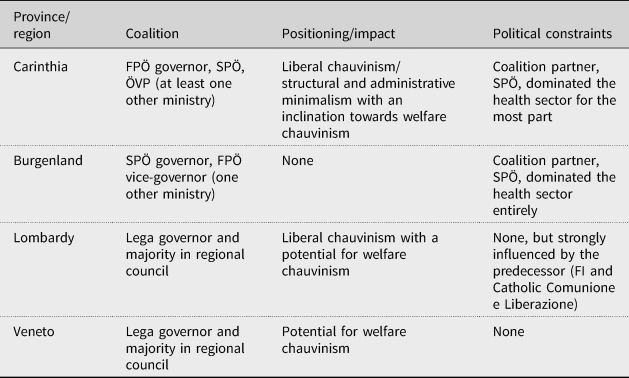

This article has demonstrated how two very prominent and popular PRR parties (the Lega in Italy and the FPÖ in Austria) have influenced health politics at the subnational level (Table 6). The findings establish that the magnitude of PRR influence on health very much depends on whom parties form coalitions with and how much authority they are actually given within the local health ministry. In Austria, health policies are made on the national level and thus, concrete subnational health policies were non-existent; in Italy, no evidence was found that institutional constraints limited the power of the PRR with regards to health. The exception here is Lombardy, where the Catholic Comunione e Liberazione could be seen as a religious authority and, thus, a type of institution.

Table 6. Summary of Findings

Based on the literature on the consequences of PRR parties and their approach to social policy, the expectation was that these parties would also pursue welfare chauvinistic policies with regards to healthcare, specifically when in a coalition with the Christian democrats. While this is most certainly in line with their intentions, this article found that the PRR parties in subnational governments were generally unable to pass desired policies or even attain a position where they could pass such policies due to coalitional and institutional constraints. Instead, PRR parties in coalition with Christian democrats (Carinthia) or PRR governors with strong predecessors from Christian democratic parties (Lombardy) tended more towards liberal chauvinist policies.

While the FPÖ in Austria followed a mostly welfare chauvinistic approach to healthcare during its time in national government (2017–19) (Falkenbach and Heiss Reference Falkenbach, Heiss, Falkenbach and Greer2021), the same could not be said for the subnational consequences. To begin with, in Austria, health policies are mainly made at the national level, so it was expected that the influence at the subnational level would be less. Second, in both Austrian cases (Burgenland and Carinthia), the FPÖ did not control the health sector. In Burgenland, this occurred because the FPÖ was simply the weaker coalition partner. In Carinthia, the situation was slightly different. Although the FPÖ did not control the health sector, it attempted to reform the hospital structures through its prominent role on the hospital advisory boards. The FPÖ's goal was to cut hospital expenditure through closures, mergers or simply by slimming down bureaucratic structures to redirect funds to support its ‘Carinthia first’ mentality. Thus, while it appears that the Carinthian FPÖ was taking a typically conservative retrenchment approach, it was actually attempting to cut in one area (hospital care) so that it could redistribute to other (social policies, labour market activation, tourism) sectors. In essence, the argument can thus be made that the Carinthian FPÖ took an indirect welfare chauvinistic approach to health. It attempted to redirect funds to sectors that it controlled, thereby increasing benefits for some while decreasing them for others. What ultimately hindered the Carinthian FPÖ from being successful was the strength and resilience of its coalition partner, the SPÖ.

In the cases of Italy, the two Italian regions of Lombardy and Veneto followed similar political trajectories in relation to health. Both regions were in the hands of the centre-right FI, from 1995 until at least 2010, when Lega presidents took over. Despite having the same parties in power, the two regions' healthcare systems developed very differently and with very contrary foci.

In Lombardy, President Formigoni created a healthcare system unique to Italy. He followed a quasi-market model wherein patients could choose whether they wanted to use public or private hospital facilities. The system he created revolved around the hospital as the centre for care, thereby deeming general practitioners useless. The result was an unbalanced system as only hospital care was given support. Formigoni's successor, Roberto Maroni, realized this and tried to balance out the system. His term ended after several failed attempts to move care outside of the hospital to accommodate the growing elderly and chronically ill population. An even less successful Attilio Fontana took over as president of the region in 2018. A weak presidential presence coupled with ineffective advisers and an ill-equipped system led Lombardy to become the poster child of pandemic failures during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. The failure of the Lega to change the Lombard health system can be primarily attributed to institutional barriers in the form of the Catholic Comunione e Liberazione.

In Veneto, Giancarlo Galan, without influence from ultra-conservative Catholic groups, created a more integrated healthcare system. Four levels of care created a more balanced system wherein the GP was given the traditional role of gatekeeper and seen as an essential part of the system. The historically more communal and interconnected region made it necessary to create a connected and more community-oriented healthcare system. When Luca Zaia replaced Galan in 2010, he expanded this system, making it even more patient-centred and organized. Unlike his colleagues in Lombardy, he did not see a need to change the existing system as it worked well. This efficiency was supported during the pandemic's first wave when, despite being a severely affected region, case numbers and death tolls were marginal compared to Lombardy's. It could be argued that the Lega in Veneto was also presented with institutional barriers in the sense that it had to continue with the health system it was given because it was effective, efficient and well-liked by the populace. So, while it might have wanted to make changes, it did not because the system was successful.

This article contributes to the literature surrounding the impact of PRR parties in government. It not only looks at the understudied area of health policy, but it does so at the subnational level. Both the consequences of PRR governments on healthcare and health policy and the focus on subnational PRR governments expand the perspective of studies of the PRR. The findings affirm that parties continue to matter when thinking about policy impact and suggest that PRR parties are generally constricted by either their coalition partner (as was the case in Austria) or institutions (as was the case in Italy). However, further research is necessary before generalizations can be made from these findings. Future articles can and should explore PRR parties' impact on subnational governments during the COVID-19 pandemic. This approach would serve as a good indicator relating the impact of a specific party in power (PRR) to a particular health phenomenon (COVID-19), thereby further expanding the literature on the impact of PRR parties on health policy.

The PRR is a minority in most places so, just as its presence depends on electoral rules, the effects of its participation in government depends on coalition politics. In all cases (except Burgenland) the PRR parties are consistently chauvinistic (despite seeming to prefer welfare to liberal chauvinism, they typically implement the latter with regards to health policies) and the generosity factor comes from a social democratic coalition partner or not at all.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2021.56.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful for the valuable feedback from Scott L. Greer, and the anonymous reviewers. Thank you to those who gave their time to be interviewed for this article.