Although populism is one of the trendiest research topics in contemporary literature, populist parties are still largely analysed through approaches that treat them, almost a priori, as ‘challengers’ or ‘outsiders’. Indeed, while excellent analyses of various aspects of the populist phenomenon abound (e.g. Albertazzi and McDonnell Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2015; Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn2016; Eatwell and Goodwin Reference Eatwell and Goodwin2018; Hawkins et al. Reference Hawkins, Carlin, Littvay and Rovira Kaltwasser2019; Kriesi Reference Kriesi2014; Moffitt Reference Moffitt2016; Mudde Reference Mudde2007; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019; Pappas Reference Pappas2019; Rooduijn Reference Rooduijn2019; Rovira Kaltwasser et al. Reference Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy2017; van Kessel Reference van Kessel2015), the literature seems not to have sufficiently theorized or empirically investigated a decisive development: the fact that an increasing number of populist parties are no longer at the margins of party systems; they are instead – as never before – integrated into their national political systems.

In this contribution, I shall respond to the recent call for a ‘paradigmatic shift’ in the study of populist parties (Mudde Reference Mudde2016: 16) and push the agenda forward by complementing the ideational approach with an analysis of the different interaction streams characterizing such actors. First, this review article provides an overview of 66 contemporary populist parties by adopting a wide-ranging pan-European perspective covering EU member states and micro-states, as well as extra-EU countries. In order to capture the salient ideational varieties of populist parties, subtypes within the general categories of right-wing and left-wing are identified, and the new category of ‘valence populism’ is introduced. Next, the limitations of the common approaches to the study of the role of populist parties in party systems, such as ‘anti-establishment’, ‘challenger’ and ‘outsider parties’, are discussed. Subsequently, building upon and expanding my previous works on the topic (Zulianello Reference Zulianello2018, Reference Zulianello2019a, Reference Zulianello2019b), the 66 populist parties under analysis are classified according to their different interactive patterns, and the key differences between non-integration, negative integration and positive integration are discussed. Finally, a brief summary is provided.

Mapping the ideational varieties of populist parties in contemporary Europe

Although definitional controversies will probably never be finally settled, an increasing number of scholars agree with the so-called ‘ideational’ approach to populism (Hawkins et al. Reference Hawkins, Carlin, Littvay and Rovira Kaltwasser2019; Mudde Reference Mudde, Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy2017). According to this, populist parties emphasize a moral and Manichaean contraposition between the ‘pure people’ and the ‘corrupt elite’ as well as the view that the essence of politics is honouring popular sovereignty (Mudde Reference Mudde2004: 543). Although any political actor may occasionally adopt populist rhetoric and messages, by adopting the ideational approach it is possible to identify the political parties for which populism represents a core ideological concept (Mudde Reference Mudde2004, Reference Mudde2007) and, as such, constitutes a decisive feature of their belief system and identity. Following an ‘inclusive’ approach to ideology (Sainsbury Reference Sainsbury1980: 8), it thus becomes possible to identify the ideas that are central for the identity of a party, even those that claim a ‘post-ideological’ or ‘non-ideological’ character (which is, ironically, an ideological claim in itself), such as the M5S in Italy (Zulianello Reference Zulianello2019a: 32), GERB in Bulgaria (Todorov Reference Todorov and Lisi2018), MOST in Croatia (Grbeša and Šalaj Reference Grbeša and Šalaj2017) and ANO 2011 in the Czech Republic (Siaroff Reference Siaroff2019).Footnote 1

Given its nature as a thin-centred ideology, populism is commonly attached to other, additional, ideological elements (thick or thin) that are crucial for its capacity to convey political meaning to the voters (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2013). From this follows the ‘highly chameleonic’ nature of populism (Taggart Reference Taggart2004: 275), which is shown by the fact that political parties that match the ideational definition can be found on the left, such as Podemos in Spain (e.g. Katsambekis and Kioupkiolis Reference Katsambekis and Kioupkiolis2019), on the right, such as the Danish DF (e.g. Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn2016), or can be impossible to locate meaningfully along the left–right continuum, such as the Italian M5S (Mosca and Tronconi Reference Mosca and Tronconi2019).

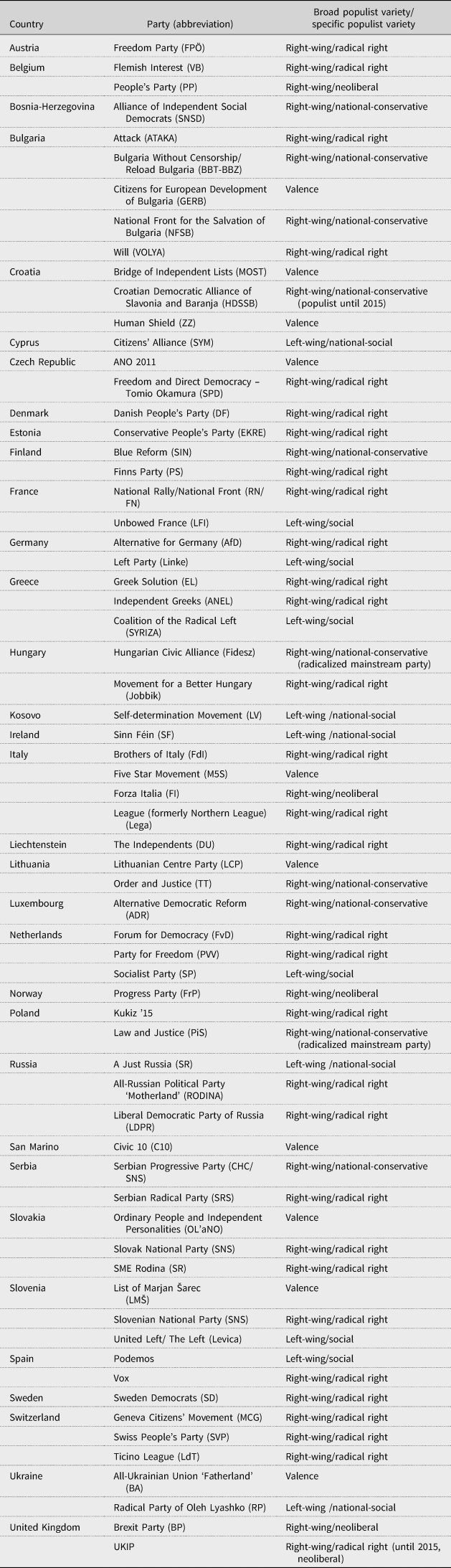

Hence, mapping the different ideational varieties of populist parties represents a decisive step towards understanding their impact on the structure of political conflict (Roberts Reference Roberts and de la Torre2018). In this respect, Table 1 adopts an unprecedented broad pan-European perspective, and provides an overview of the populist parties matching the ideational definition that obtained parliamentary seats in at least one of the following: the most recent national general election (lower house, up to 29 May 2019), the 2014 EU election or the 2019 EU election.

Table 1. Ideational Varieties of Populist Parties that Obtained Parliamentary Representation in at Least One of the Following: the Most Recent National General Election (Lower House), the 2014 EU Election or the 2019 EU Election

Sources for the identification of populist parties in EU and EFTA countries: I largely followed the list compiled by Rooduijn et al. (Reference Rooduijn, van Kessel, Froio, Pirro, De Lange, Halikiopoulou, Lewis, Mudde and Taggart2019), with a few modifications. First, I included three populist radical right parties that were not included in the list because they received less than 2% of the votes: the Dutch FvD, and two Swiss parties, the LdT and the MCG (Zulianello Reference Zulianello2019a). Second, I also classified the Bulgarian Volya, a member of the Movement for a Europe of Nations and Freedom, as populist. Third, I excluded the Icelandic Centre Party and People's Party because they do not seem to be ideational instances of populism, although they present populist ‘tendencies’ (Ólafur Harðarson, personal communication, 5 April 2019). Finally, I added two populist parties from micro-states: Civic 10 in San Marino (Civico 10 2019) and Independent Lists in Liechtenstein (Siaroff Reference Siaroff2019), and three parties that obtained seats in the 2019 European Parliament elections: the Brexit Party in the UK (Jacobson Reference Jacobson2019), Greek Solution (2019) and Vox in Spain (Turnbull-Dugarte Reference Turnbull-Dugarte2019).

Sources for the other countries: Bosnia-Herzegovina: Siaroff (Reference Siaroff2019); Kosovo: Yabanci (Reference Yabanci2015); Russia: March (Reference March2011, Reference March, Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy2017); Serbia: Stojić (Reference Stojić2018); Ukraine: March (Reference March, Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy2017).

Sources for the classification of populist varieties: I drew from various sources, although the ultimate decision was mine: Goodwin and Dennison (Reference Goodwin, Dennison and Rydgren2017), Grbeša and Šalaj (Reference Grbeša and Šalaj2017), de Jonge (Reference de Jonge2019); Katsambekis and Kioupkiolis (Reference Katsambekis and Kioupkiolis2019), March (Reference March2011), Mudde (Reference Mudde2007), Rovira Kaltwasser et al. (Reference Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy2017), Rooduijn et al. (Reference Rooduijn, van Kessel, Froio, Pirro, De Lange, Halikiopoulou, Lewis, Mudde and Taggart2019), Stojić (Reference Stojić2018), van Kessel (Reference van Kessel2015), Zulianello (Reference Zulianello2019a). On ‘radicalized mainstream parties’, see Bustikova and Guasti (Reference Bustikova and Guasti2017), see also Pytlas (Reference Pytlas, Herman and Muldoon2018).

As Table 1 suggests, 66 contemporary parties from 33 European countries can be considered to be ideationally populist, and they can be distinguished into three broad groups: right-wing (45 out of 66, 68.2%), left-wing (11 parties, 16.7%) and valence populism (10 parties, 15.2%).Footnote 2 Before proceeding, it is worth underlining that I focus on such broad categories because they are particularly suited for the analysis of party systems and party competition. In ‘positional’ terms, my conception of ‘left’ and ‘right’ follows Norberto Bobbio's (Reference Bobbio1996) approach in defining it in terms of relative propensity towards egalitarianism, an understanding that, in my view, also includes but does not correspond tout court to the distinction between ‘inclusionary’ and ‘exclusionary’ populism (cf. Font et al. Reference Font, Graziano and Tsakatika2019; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2013).

The first broad group is represented by right-wing populist parties, which includes three more specific varieties: the ‘populist radical right’ (31 out of 45), ‘neoliberal’ populists (four parties) (Mudde Reference Mudde2007), and ‘national-conservative populists’ (10 parties) (see Pankowski and Kormak Reference Pankowski, Kormak, Melzer and Serafin2013: 162), although two of them (Fidesz and PiS) are best understood as ‘radicalized mainstream parties’ (see Bustikova and Guasti Reference Bustikova and Guasti2017). The second group includes left-wing populists, which combine populism with variously defined forms of socialism. While six out of the 11 parties that fall in this category qualify as typical ‘social populists’ (Mudde Reference Mudde2007), five are best understood as ‘national-social populists’, as they complement left-wing populism with various forms of nationalism (March Reference March2011).

I introduce the term of valence populism to refer to the third cluster of actors (10 out of 66). As Kenneth Roberts (Reference Roberts and de la Torre2018: position 5260) maintains, whereas all populist parties ‘present elements of valence competition’, right-wing and left-wing populists also ‘have a positional character that politicizes a specific pole on their primary competitive axis’. However, some parties ‘offer little more than … valence considerations’ and cannot be classified as right or left, nor exclusionary or inclusionary, as they ‘defy positional definition altogether’ (Roberts Reference Roberts and de la Torre2018: position 5260). Accordingly, I operate a distinction between ‘positional’ populists (left-wing and right-wing varieties) and those that I shall define as instances of ‘valence’ populism – parties that predominantly, if not exclusively, compete by focusing on non-positional issues such as the fight against corruption, increased transparency, democratic reform and moral integrity, while emphasizing anti-establishment motives. This definition is similar to that of ‘centrist’ populist parties (Stanley Reference Stanley, Kaltwasser C, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy2017; see also Hanley and Sikk Reference Hanley and Sikk2016), but the term ‘valence populism’ seems more appropriate, as the former etiquette ‘directly or indirectly refers to the ideological or geometric center of the party system’ (Učeň Reference Učeň, Gyárfášová and Mesežnikov2004: 47). Nevertheless, the notion of ‘centre party’ should be restricted to an ‘ideologically positioned party’ (Hazan Reference Hazan1997: 27, emphasis added), while the distinctive feature of valence populists is precisely the prevailing emphasis on non-positional issues, such as competence and performance. To be clear, this is not to deny that valence populists may adopt specific positions; however, their policy stances are primarily informed by an unadulterated conception of populism (with other ideological elements, if any, playing a marginal or secondary role), and are therefore flexible, free-floating and, often, inconsistent. Valence populists thus subscribe to a ‘pure’ version of populism (cf. Tarchi Reference Tarchi2015; see also Curini Reference Curini2018), meaning that they are neither right-wing nor left-wing, neither exclusionary nor exclusionary.

Examining populist parties from a systemic perspective: common approaches

Whereas the ideational approach does a very good job of the key task of identifying which parties can be classified as populist, the existing literature has largely focused on the programmatic reaction of the so-called ‘mainstream’ parties (e.g. Bale et al. Reference Bale, Green-Pedersen, Krouwel, Luther and Sitter2010; de Lange Reference de Lange2012; Han Reference Han2015) or the impact of populist parties on party systems (e.g. Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn2016; Mudde Reference Mudde2014; Wolinetz and Zaslove Reference Wolinetz and Zaslove2018). However, the persistence of scholars in analysing populist actors, almost a priori, using analytical tools that are grounded on over-simplistic assumptions that do not appropriately represent empirical reality, such as the categories of anti-establishment, challenger and outsider parties, is striking.

Anti-establishment parties

Recent years have witnessed the proliferation of alternative ‘anti’ labels (for an overview, see Zulianello Reference Zulianello2019a: ch. 2). Among them, one of the most popular is represented by that of ‘anti-political establishment party’ (APE), first proposed by Andreas Schedler (Reference Schedler1996) and later revised by Amir Abedi (Reference Abedi2004). Whereas Schedler's notion presents ‘characteristics largely synonymous with what many would consider populist parties’ (McDonnell and Newell Reference McDonnell and Newell2011: 445), Abedi (Reference Abedi2004) defines an APE party as an actor that simultaneously: (1) ‘challenges the status quo in terms of major policy issues and political system issues’; (2) ‘perceives itself as a challenger to the parties that make up the political establishment’; and (3) ‘asserts that there exists a fundamental divide between the political establishment and the people’ (Abedi Reference Abedi2004: 11).

Despite the valuable attempt to combine the assessment of a party's profile with its role in the party system, a number of shortcomings emerge. It can be seen that, although Abedi's approach combines an assessment of both the substantive profile of a party (properties 1 and 3) as well as its role played in party competition (property 2), a disproportionate weight is placed on the latter when the issue of reclassification arises. Indeed, if we review his classification of political parties between APE and establishment actors (Abedi Reference Abedi2004: 143–149, see 11), it emerges that Abedi reclassifies a party of the former group into the latter as soon as it takes part in national government or even ‘cooperates’ with establishment parties, even if such a development is not accompanied by a substantive transformation of its ideological profile. In this respect, it is clearly an oversimplification to conclude that actors such as the Austrian FPÖ or the Finnish PS became ‘establishment parties’ comparable to the Austrian People's Party (ÖVP) or the National Coalition Party (KOK) as a mere consequence of their participation in the coalition game with the latter actors. This point is well summarized by Tjitske Akkerman (Reference Akkerman, Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn2016: 268, 277), who argues that when right-wing populist parties change ‘their anti-establishment behaviour’, meaning that they leave behind ‘their lone opposition and increasingly cooperate with other parties’, they usually do so while maintaining their radical positions and without ‘moderat[ing] their anti-establishment ideology’. Better still, precisely because of their ideational features, populist parties remain characterized by a clear anti-establishment mentality even if they take part in the coalition game and/or national government.

Challenger parties

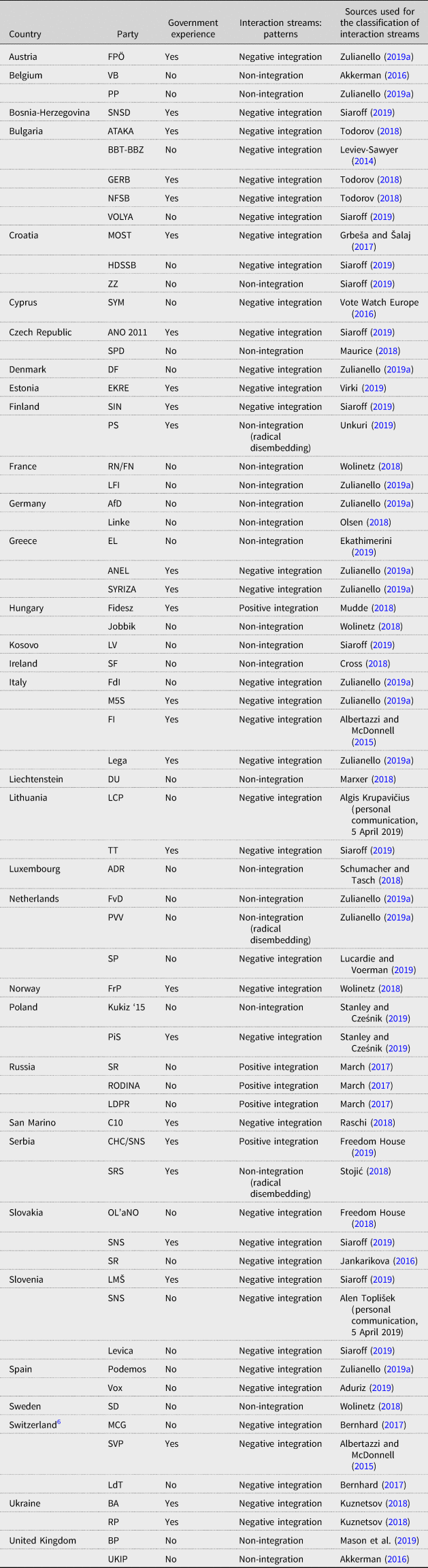

Sara Hobolt and James Tilley (Reference Hobolt and Tilley2016: 974) argue that by focusing on the parties that have not previously held political office, defined as ‘challengers’, it is possible to ‘indirectly capture many of the features of … populist parties’. Nevertheless, scholars should avoid using the term ‘challenger’ with the expectation that they are automatically referring to populist parties. As highlighted later in the text (Table 2), 40.9% of contemporary European populist parties do not qualify as challengers, as they have government experience at the national level. Furthermore, three additional serious shortcomings can be identified. First, the ‘challenger’ perspective overlooks the fact that populist parties may well continue, in ideational terms, to question the ‘mainstream consensus’, to echo the words of Hobolt and Tilley (Reference Hobolt and Tilley2016: 972), despite their inclusion in the area of government. Second, among the challengers matching the ideational definition, populist parties that are key players in the coalition game despite the absence of previous governmental experience (e.g. the Danish DF) are equated with actors that are non-coalitionable and, as such, marginalized or self-marginalized in the party system (e.g. the Swedish SD). Finally, and more generally, under the label of ‘challengers’ fall parties that have very little – if anything – in common, ranging from eminently ideologically moderate actors, such as the centrist Mario Monti's Civic Choice in Italy, to blatantly extremist actors, such as the extreme right Golden Dawn in Greece.

Table 2. Previous or Current Governmental Experience and Contemporary Interaction Streams of the Populist Parties (as of 29 May 2019, presentational order follows Table 1)

Outsider parties

Steven Wolinetz (Reference Wolinetz, Wolinetz and Zaslove2018: 285–286) identifies three areas within a party system with the goal of examining the ‘impact of populist parties on party systems’: ‘the core’, consisting of ‘insider’ parties that ‘govern or oppose’ and ‘rotate in and out of office’; an ‘intermediate zone’ consisting of parties that ‘could govern but don't do so often’; and ‘outsiders’ – actors that ‘represent and never govern’.

At first sight, parties falling into the intermediate zone should be classified as neither ‘outsider’ nor ‘insider’ following the definitions above; however, Wolinetz (Reference Wolinetz, Wolinetz and Zaslove2018) specifies that both actors that ‘never govern’ as well as those that ‘rarely’ govern qualify equally as outsiders. However, this choice results in lumping together – under the umbrella of ‘outsider parties’ – populist parties that have actually played substantially different roles for the functioning of party systems, such as those that supported formalized minority governments (e.g. the Danish DF), participated as full members in governing coalitions (e.g. the Norwegian FrP), as well as those that have been consistently excluded or self-excluded from the coalition game and are thus located at the margins of the party system (e.g. Jobbik in Hungary).

That said, according to Wolinetz (Reference Wolinetz, Wolinetz and Zaslove2018), only the People of Freedom (PdL)/Forza Italia in Italy, the Swiss SVP and Fidesz in Hungary should be classified as insiders. However, it is unclear why the Northern League, now the oldest parliamentary party in Italy with a long record of participation in national government, is classified as an ‘ambiguous or mixed’ case, as is the use of the same categorization for the Polish PiS. The fact that Wolinetz (Reference Wolinetz, Wolinetz and Zaslove2018: 281) argues that both these parties ‘self-define’ as outsiders despite the key role they have played in their national party systems adds further confusion, as any populist party (irrespective of its location) would attempt to deliver this image given the inherently anti-elitist or anti-establishment nature of its ideational profile. Finally, it is worth underlining that the fact that populist parties in the intermediate zone ‘would share power if they could do so on terms they could accept’ (Wolinetz Reference Wolinetz, Wolinetz and Zaslove2018: 285) is hardly unique to such actors and can be extended to any political actor possessing coalition potential. I shall return to this crucial point later.

Another approach to outsider parties is provided by Duncan McDonnell and James Newell (Reference McDonnell and Newell2011: 445, emphasis added), who define them as the parties that ‘have placed themselves and/or been placed by others, “outside” the sphere of potential governing parties’ and that present ‘transformative aspirations’ as they do not offer just ‘alternative “policies” … but alternative “metapolicies”’. Such a definition is explicitly bi-dimensional and presents various advantages over the other ‘anti’ labels discussed so far. First, the authors do not focus simply on governmental ‘relevance’ (i.e. the actual participation in office) but also on government ‘potential’, thus allowing a more appropriate understanding of the workings of party systems. Second, the choice to refer to ‘metapolicies’ to grasp the ‘transformative aspirations’ of outsiders (McDonnell and Newell Reference McDonnell and Newell2011: 445) appears particularly apt. Nevertheless, as with the other concepts discussed in the previous pages, conceptual boundaries remain unspecified. As McDonnell and Newell (Reference McDonnell and Newell2011: 447, 451) admit, outsider parties may: ‘join government while retaining or attempting to retain significant features of an outsider status … This poses the puzzle for researchers of assessing whether in such cases a party effectively stops being an outsider.’

Combining the ideational approach with the analysis of systemic interactions

The previous pages highlighted that the most common analytical tools used by scholars to assess the different roles played by populist parties in national party systems ultimately adopt dualistic lenses which do not do justice to empirical reality. Building upon and expanding from my previous works (Zulianello Reference Zulianello2018, Reference Zulianello2019a, Reference Zulianello2019b), I argue that a classificatory effort aiming to grasp the different roles played by populist parties in contemporary party systems requires the assessment of two distinct dimensions that may well vary independently from one another.

The first dimension is represented by the determination of the ideological orientation of a party towards crucial features of the status quo which, following Newell and McDonnell (2011), can be grouped under the umbrella term ‘metapolicies’. Although the latter term can be used to assess the orientation of any political party towards key ‘values and/or practices of the political, social, or economic system that are enshrined by the existing order’ (Zulianello Reference Zulianello2019a: 31), for the present purposes it suffices to say that, within liberal-democratic contexts, populist parties can be understood as instances of ideational opposition to a specific metapolicy – the political regime – in particular to key values such as the legitimacy of constitutional limitations to popular sovereignty and the safeguard of pluralism. Obviously, populist parties may well question other metapolicies in addition to the political regime – for example the political community (e.g. populist parties that also qualify as secessionist, such as the Flemish VB) – however, the minimal common denominator is the challenge posed, in ideational terms, to the political regime, which is sufficient to deem a populist party an instance of anti-metapolitical opposition.

The second dimension focuses on the qualitatively different functional roles played by political parties at the systemic level. Political parties can be distinguished on the grounds of the absence or presence of the property of ‘systemic integration’, which refers to various scenarios in which a political party is integrated in cooperative interactions at the systemic level (Zulianello Reference Zulianello2018, Reference Zulianello2019a). In this respect, the crucial test is represented by the assessment of the interaction streams at the national level, as a given political party may be ‘coalitionable’ at the subnational or regional level but ‘uncoalitionable’ (for whatever the reason) in the national party system.

The property of systemic integration does not simply characterize the actors that historically played a prominent and active role in the coalition game – that is, ‘core system’ parties (see Smith Reference Smith1989: 161)Footnote 3 – but also those that took part in formal minority governments, fully fledged coalition governments, pre-electoral coalitions, or possess (and do not refuse in principle to use) coalition potential, with mainstream actors.Footnote 4 For the sake of clarification ‘mainstream parties’ here means the parties that occupy an ‘overall advantageous position in the system’ (de Vries and Hobolt Reference de Vries and Hobolt2012: 250, emphasis added).Footnote 5

Although the most common path towards the achievement of systemic integration is constituted by the development and availability to use coalition potential (see below), a party can also achieve systemic integration through another, less frequent, path: through ‘very visible and direct actions’ while in national government (Zulianello Reference Zulianello2019a: 34–36) that result in its actual and active contribution to the continuity of the key features of the existing order, despite its principled refusal to cooperate with mainstream actors, as in the case of SYRIZA in 2015 (for details, see Zulianello Reference Zulianello2018, Reference Zulianello2019a: ch. 4).

As coalition potential is very central to my argument, it is important to clarify its meaning. Here, I follow Nicole Bolleyer (Reference Bolleyer and Deschouwer2008: 25) in stressing the fact that it corresponds to a ‘potential in the sense of the word’. On the one hand, once a party possesses coalition potential, it has achieved a ‘general acceptance as a political force’ (Bolleyer Reference Bolleyer and Deschouwer2008: 25) from the perspective of core-system parties and/or mainstream parties. On the other hand, its full development requires that the same party is equally available to a potential, reciprocal and formalized cooperation with the latter actors. In other words, ‘coalition potential’ here means that there is no a priori rejection of a potential cooperation, either from the side of mainstream or core-system parties, or from the party x itself. Once a party possesses coalition potential and is available to the possibility of using it, concretization into actual pre-electoral coalitions or coalition governments (i.e. governmental relevance) becomes simply dependent on other ‘pragmatic’ considerations (e.g. number of seats, programmatic compatibility, incentives of the political system). In other words, it is no longer a matter of the ‘legitimacy’ of a given party, but becomes merely a matter of (normal) politics.

This leads us to the question of how we can empirically grasp coalition potential. The answer is the assessment of the ‘public relationships’ between political parties at the national level (Zulianello Reference Zulianello2019a: 35) – that is, the visible interactions taking place within the party system. In terms of operationalization, if a populist party is integrated in cooperative interactions at the systemic level, it is usually an event that receives media coverage and, as such, high visibility at the public level (cf. Sartori Reference Sartori1976). Thus, this information is commonly contained in scholarly contributions, but in case of recent events or little-studied countries, reliable media reports fit the purpose well (see Table 2).

In sum, the property of systemic integration captures functional equivalents across the various contexts, and once achieved is in most cases maintained by political parties, given the competitive advantages it provides (i.e. as a credible coalition partner and/or governing party). However, although empirically rare, a political party may deliberately relinquish systemic integration through the process of ‘radical disembedding’ (a specific modality of non-integration), by distancing itself from its previous involvement in cooperative interactions at the systemic level through the radicalization of its ideological profile and its concomitant move to the margins of the party system through the adoption of an isolationist and non-cooperative stance (Zulianello Reference Zulianello2019a: 36–37, 110–111; see also Reference Zulianello2018).

The focus on these two dimensions resulted in a typology capable of classifying political parties in general (for details, see Zulianello Reference Zulianello2018, Reference Zulianello2019a) but, for the present purposes, the crucial point is that it makes it possible to account appropriately for the different interaction streams of populist parties across national party systems. This represents a decisive development in the scholarly debate, as Table 2 suggests that scholars’ persistence in analysing populist parties by adopting the challenger–outsider paradigm is indeed unwarranted, given the fact that 40.9% of populist parties in Europe have previous or current experience as fully fledged government actors (37.3% in EU member states). Furthermore, this tells only part of the story, as it focuses only on a very narrow outcome (governmental relevance) that overlooks crucial interactions taking place at the systemic level. Indeed, across all European countries, a clear majority (66.7%) of contemporary populist parties present the property of systemic integration, meaning that they are involved in very visible cooperative interactions (62.7% in EU member states). Conversely, only a minority of contemporary populist parties (across all countries, 33.3%; 37.3% in EU member states) lack the property of systemic integration, and are relegated, either because of their volition or that of the others, to the margins of the party system.

Non-integrated, negatively integrated and positively integrated populist parties

The discussion so far has highlighted that the integration or non-integration of populist parties needs to be evaluated by focusing on a more sophisticated approach than the typical challenger–outsider paradigm. By focusing on the interplay between the ideational profile of a party, its interaction streams and the features of the metapolitical system, it is possible not only to distinguish between populist parties that present the property of systemic integration from the others, but also to identify three, very different, patterns: non-integration, negative integration and positive integration (Table 2).

Non-integrated populist parties

Non-integrated populist parties are characterized by a ‘double image of externality in comparison to the “system”: in terms of their core ideological concepts as well as in terms of their direct and indirect visible interactions with the system itself’ (Zulianello Reference Zulianello2019a: 38). Such populist parties technically qualify as anti-system following my revisited concept (Zulianello Reference Zulianello2018, Reference Zulianello2019a) as they not only challenge the political regime (and possibly other metapolicies, according to the specific cases), but also, given the absence of systemic integration, represent a systemic constraint, especially in view of a possible expansion of the area of government and, in some cases, for routine governance. It is worth underlining that, although my revisited conceptualization of anti-system parties differs from classical approaches in various respects, it shares with the Sartorian conceptualization (Sartori Reference Sartori1976, Reference Sartori1982) an emphasis on conceiving the term ‘system’ and its negation ‘anti-system’ as ‘neutral’ and ‘relative’, meaning, inter alia, that ‘anti-system’ is not a synonym of ‘anti-democratic’, ‘outside the system’ or ‘revolutionary’ party (for details, see Zulianello Reference Zulianello2019a: ch. 2; Reference Zulianello2019b).Footnote 7

As previously mentioned, a minority of contemporary populist parties (33.3%) qualify as anti-system and hence non-integrated, with the majority of them (15 out of 22) found in Western European EU member states. In terms of ideational varieties, the large majority (17 out of 22) of non-integrated actors are right-wing parties (among them, 14 out of 17 belong to the populist radical right variety), followed by four cases of left-wing populism (the German Linke, Irish SF, LFI in France, LV in Kosovo) and one case of valence populism (ZZ in Croatia). Furthermore, whereas the vast majority of non-integrated populist parties (19 out of 22) never achieved systemic integration, three populist radical right parties (re)gained anti-system status through the process of radical disembedding. This is the case for the Dutch PVV, the Finnish PS and the Serbian SRS, which, despite their previous achievement of systemic integration, deliberately relinquished it by radicalizing their ideational orientation vis-à-vis the existing ‘system’ and simultaneously embracing an isolationist and non-cooperative posture (for details, see Zulianello Reference Zulianello2019a).

Negatively integrated populist parties

If the focus is placed on fully fledged liberal-democratic contexts, populist parties presenting the property of systemic integration are by definition negatively integrated. The adjective ‘negative’ refers to the fact that despite their involvement in a qualitatively different set of interaction streams (as indicated by the possession of systemic integration) in comparison to anti-system populist parties (i.e. non-integrated populists), in ideational terms they nevertheless continue to challenge the constitutional limitations of popular sovereignty and pluralism: the values embodied by the liberal-democratic regime (and possibly additional metapolicies, according to the individual cases).Footnote 8

Within the contexts under analysis that can be considered as fully fledged liberal democracies – thus excluding Bosnia-Herzegovina, Hungary, Kosovo, Russia, Serbia and Ukraine (Freedom House 2019) – the status of negative integration characterizes around two-thirds (65.5%, 36 out of 55) of contemporary populist parties: 23 of the right-wing variety, 8 instances of valence populism and 5 left-wing actors. Such populist parties achieved negative integration through various forms of cooperative interactions with mainstream parties, including but not limited to full participation in national government with the latter actors (e.g. the Estonian EKRE in the aftermath of the 2019 general elections), such as the possession of (and absence of a principled refusal to use) coalition potential as previously defined (e.g. Vox in Spain before the 2019 general election); participation in pre-electoral coalitions (e.g. FdI in Italy); support of formalized minority governments (e.g. Levica in Slovenia); or, despite the attempt to bypass mainstream parties, as a consequence of a direct and active contribution to the continuity of the ‘system’ itself through very visible actions while in office (e.g. SYRIZA in Greece). It is worth adding that, in some cases, populist parties did not have to undergo a temporal period before achieving systemic integration, as they already possessed it: for example, SIN in Finland was formed by defectors from the PS while the latter party was in government coalition with mainstream parties, and the Swiss SVP was already part of the so-called ‘magic formula’ once it transformed itself into a populist radical right party.

Whereas in fully fledged liberal democracies the integration of populist parties is by definition of the negative type (see above), in national contexts that cannot be considered as either consolidated or consolidating democracies, a more nuanced pattern emerges. Indeed, in addition to non-integrated parties (e.g. Jobbik in Hungary), it is possible to find not only instances of negative integration (e.g. the SNSD in Bosnia-Herzegovina), but also actors who are indeed positively integrated ‘in the system’.Footnote 9

Positively integrated populist parties

The status of positive integration characterizes only five contemporary European populist parties but it has great substantive importance, especially for democratic theory. The use of the adjective ‘positive’ refers to the fact that these parties are in a symbiotic relationship with the existing status quo, its values and practices.Footnote 10 Better still, in the case of Fidesz in Hungary and the Serbian CHC/SNS, it is more appropriate to say that precisely these parties changed ‘the sources of legitimation upon which the political regime itself is built’ (Zulianello Reference Zulianello2018: 660) by transforming the regime to match their own ideological preferences. Until recently, the case of Fidesz was still probably close to a ‘negative integration’ type given the peculiar nature of the ‘system of national cooperation’ (Zulianello Reference Zulianello2018: 672), but at the end of 2018 Hungary underwent the ‘final step towards a (competitive) authoritarian regime’ (Mudde Reference Mudde2018), following the abolition of independent judicial control over the government. Hungary has thus completed its full transformation, a qualitative change also (finally) sanctioned by Freedom House (2019), which warrants the reclassification of Fidesz as an actor that is clearly positively integrated in the system, as its illiberal values are now fully enshrined in the national political regime, despite EU membership.Footnote 11

Similarly, the Serbian CHC/SNS, in government since 2012, ‘has steadily eroded political rights and civil liberties, putting pressure on independent media, the political opposition, and civil society organizations’, with the country eventually being downgraded to ‘partly free’ by Freedom House in 2019. Finally, the other three positively integrated populist parties are found in Russia. Here, the explanation is rather straightforward, given the autocratic status of the regime; indeed, the LDPR, SR and RODINA are ‘satellites’ of the dominant United Russia, they are controlled by the Kremlin and their role is largely ornamental and supportive towards the regime (March Reference March, Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy2017).

Conclusion and discussion

In this contribution, I have taken a different approach to the study of the party politics of populism, by complementing the ideational approach to populism with the analysis of party interaction streams at the systemic level, and applied it on empirical grounds by adopting a broad pan-European perspective to 66 parties in 33 countries. First, from an ideational point of view, I argued that a more nuanced analysis of populist parties in contemporary party systems requires not only distinguishing between (subtypes) of left- and right-wing populism, but also introducing the separate category of valence populists to analyse actors such as the Italian M5S or the Croatian ZZ, which predominantly engage in non-positional competition and subscribe to an unadulterated version of populism. Second, from a party system perspective, I have stressed that scholars should avoid using labels such as anti-establishment, challenger or outsider parties with the expectation of automatically referring to the universe of populist actors. While the term ‘anti-establishment’ captures a decisive element of the ideational profile of populist parties, its usage is unwarranted if the goal is to understand the different roles played by such actors in contemporary party systems. Indeed, the anti-establishment ideology is frequently disjointed from anti-establishment behaviour, as indicated by the increasing integration of populist parties into the coalition game and the governmental arena. This observation applies equally to existing approaches that seek to distinguish between challenger-outsider or insider-outsider political parties, as populist actors may well present mixed features that are not captured appropriately by such categories.

In light of these considerations, I have followed a different line, arguing that a minority of contemporary populist parties are at the margins of their national party systems, as many of them are indeed integrated in very visible cooperative interactions at the systemic level. Furthermore, I have suggested that it is necessary not only to assess whether a populist party presents the property of systemic integration, but also to distinguish between two very different patterns: negative and positive integration. In fully fledged liberal-democratic contexts, the integration of populist parties is by default of a ‘negative’ type, given that their ideational profile is at odds with both the values of pluralism and the constitutional checks and balances characterizing these regimes. However, in hybrid or fully authoritarian contexts, populist parties may well be ‘positively’ integrated into the system, meaning that they share its underlying values, as shown by the cases of Hungary, Russia and Serbia.