No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 June 2011

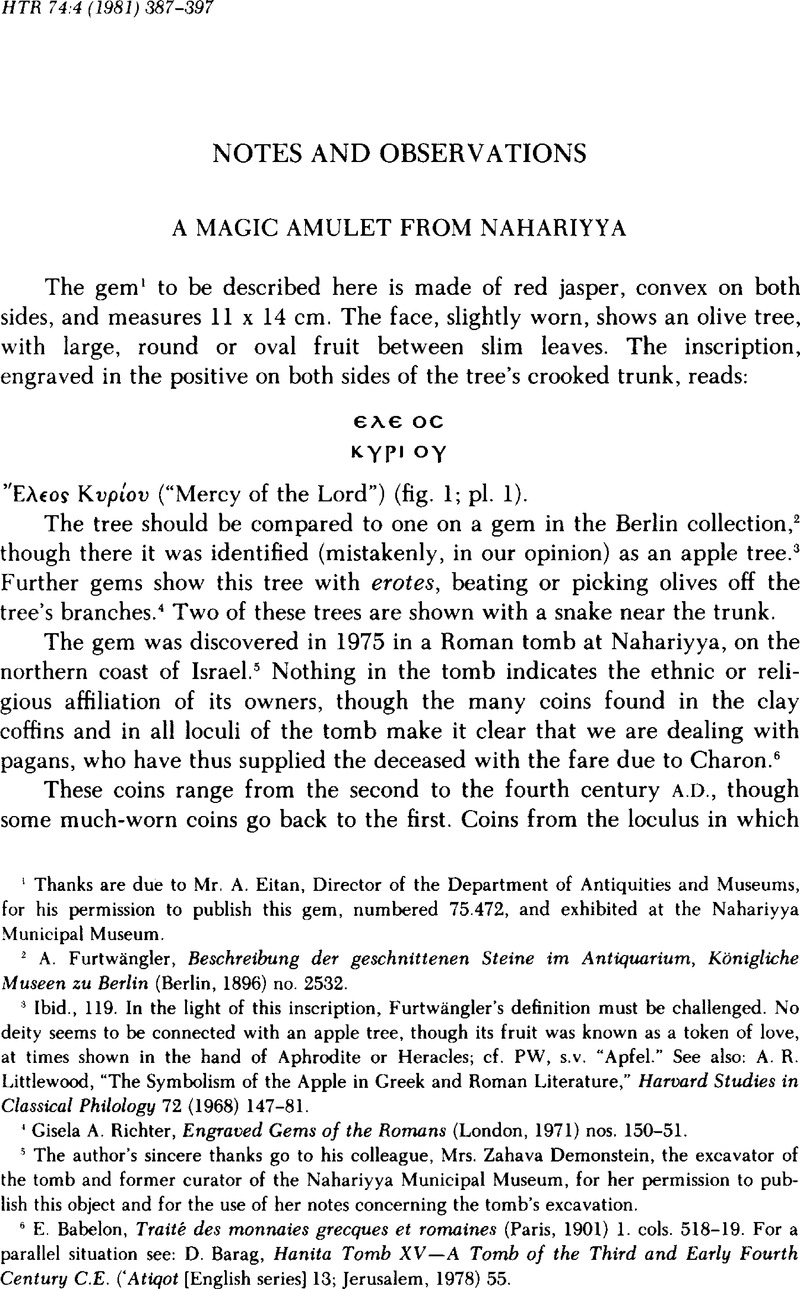

1 Thanks are due to Mr. A. Eitan, Director of the Department of Antiquities and Museums, for his permission to publish this gem, numbered 75.472, and exhibited at the Nahariyya Municipal Museum.

2 Furtwängler, A., Beschreibung der geschnittenen Steine im Antiquarium, Königliche Museen zu Berlin (Berlin, 1896) no. 2532Google Scholar.

3 Ibid., 119. In the light of this inscription, Furtwangler's definition must be challenged. No deity seems to be connected with an apple tree, though its fruit was known as a token of love, at times shown in the hand of Aphrodite or Heracles; cf. PW, s.v. “Apfel.” See also: Littlewood, A. R., “The Symbolism of the Apple in Greek and Roman Literature,” Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 72 (1968) 147–81CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

4 Richter, Gisela A., Engraved Gems of the Romans (London, 1971) nos. 150–51Google Scholar.

5 The author's sincere thanks go to his colleague, Mrs. Zahava Demonstein, the excavator of the tomb and former curator of the Nahariyya Municipal Museum, for her permission to publish this object and for the use of her notes concerning the tomb's excavation.

6 Babelon, E., Traite des monnaies grecques et romaines (Paris, 1901) 1Google Scholar. cols. 518–19. For a parallel situation see: D. Barag, Hanita Tomb XV -A Tomb of the Third and Early Fourth Century C.E. (Atiqot [English series] 13; Jerusalem, 1978) 55.

7 The author thanks his colleague, Miss Marcia Sharabani, curator of coins in the Department of Antiquities and Museums, for providing him with the identification of these coins.

8 Another feature this tomb has in common with the Hanita Tomb XV; Barag, Hanita Tomb XV, 54–55.

9 Roscher, Lexicon, s.v. “Athene,” col. 683; Nilsson, M. P., Geschichte der griechischen Religion (2d ed.; Munich, 1955) 349Google Scholar; see also 210. A connection with Eleos and his altar at Athens can be discounted, as no olive tree is reported in this context; see PW, s.v. “Eleos.”

10 Nonnos, Dionysiaca (eds. W. H. D. Rouse and R. J. Hind; LCL; London, 1942) 40. 469–534; cf. Cook, S. A., The Religion of Ancient Palestine in the Light of Archaeology (London, 1930) pi. 161Google Scholar. For a discussion of Tyre as the cult's place of origin, and the relation between the cultivation of the olive and the cult of Heracles, see Brundage, B. C., “Heracles the Levantine,” JNES 17 (1958) 231Google Scholar.

11 Cook, A. B., Zeus (Cambridge, 1940) 3. 980Google Scholar, figs. 783–89, ranging from Caracalla to Salonina.

12 Yonah, M. Avi, The Holy Land (Michigan, 1966) 130Google Scholar.

13 Chéhab, M., “Tyr à 1'époque romaine,” Mélanges de I'Université Saint Joseph 38 (1962)Google Scholar 18, citing Father Mouterde; see also W. W. von Baudissin, Kyrios (Giessen, 1929) 2. 262–69; for further examples from Byblos and Aradus, ibid., 271; cf. Renan, M. F., Mission en Phénicie (Paris, 1864) 1. 133Google Scholar, 237, where Kyria alone designates the locally well-known goddess.

14 Baudissin, Kyrios, 342. To this might be added Palmyrene inscriptions, e.g., ![]()

![]() from 188 AD, in Lidzbarski, M., Ephemeris für semitische Epigraphik (Giessen, 1902) 1. 203 and 2. 313–16Google Scholar. For full references see: Jean, C. F. and Hoftijzer, J. J., Dictionaire des inscriptions sémitique de I'ouest (Leiden, 1965) 278Google Scholar, s.v.

from 188 AD, in Lidzbarski, M., Ephemeris für semitische Epigraphik (Giessen, 1902) 1. 203 and 2. 313–16Google Scholar. For full references see: Jean, C. F. and Hoftijzer, J. J., Dictionaire des inscriptions sémitique de I'ouest (Leiden, 1965) 278Google Scholar, s.v.![]() . It may be added that the LXX uses “eleos” fairly indiscriminately to translate

. It may be added that the LXX uses “eleos” fairly indiscriminately to translate ![]() and

and ![]() , at times even in the same sentence, e.g. Isa 63:7.

, at times even in the same sentence, e.g. Isa 63:7.

15 Ginzburg, L., The Legends of the Jews (Philadelphia, 1947) 1. 93–94Google Scholar.

16 The Books of Adam and Eve” APOT 2. 142–44. For the date, Pfeiffer, R. H., History of New Testament Times (New York, 1949) 73Google Scholar; and Eissfeldt, O. E., The Old Testament (Oxford, 1965) 637Google Scholar.

17 It may be added that later Christian writings-presumably after the fifth century AD - amended the concept of the resurrection so that it would take place with the return of Christ, who would dispense the Oil of Mercy to the resurrected Adam and all believers. See “Vitae Adae” 42:2–3, APOT, 144; see also “Acts of Pilate” (The Gospel of Nicodemus), Part II: The Descent into Hell III (XIX) in James, M. R., The Apocryphal New Testament (Oxford, 1926) 126–27Google Scholar; on dating, ibid., 95.

18 Ginzburg, Legends, 5. 119, n. 113.

19 Gnostic” is used here in the sense given in Bonner, C., Studies in Magical Amulets, Chiefly Greco-Egyptian (Ann Arbor, 1950) 1, 45Google Scholar. See also: Anit Hamburger, Gems of Caesarea Maritima (Atiqot [English Series] 8; Jerusalem, 1968) 3–5.

20 Bonner, Magical Amulets, 9.

21 Ibid., 250–51.