The history of the New Testament [text] is the most perplexing of the unsolved problems of the universe and has almost as many missing links as the chain of life itself.Footnote 1 (James Rendel Harris [1852–1941], English biblical scholar)

Introduction

The New Testament manuscripts offer readings that vary from each other in a significant way.Footnote 2 Yet, many Bible readers are unaware of these differences in the ancient documents. This article presents a proposal on how editors could represent these differences in editions and translations so that these insights reach Bible readers. In this study I use Mark 1:1 to illustrate the issue.

The fifth edition of the UBS Greek New Testament (2014) prints Mark 1:1 as follows: Ἀρχὴ τοῦ εὐαγγελίον Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ [νἱοῦ θεοῦ], “A beginning of the good news about/of Jesus Christ [the son of god]” (my translation). The square brackets indicate that textual critics are not convinced of the authenticity of the enclosed words.Footnote 3 Tommy Wasserman argues for their inclusion.Footnote 4 One recent edition, the Greek New Testament Produced at Tyndale House, Cambridge, also includes them.Footnote 5 However, Bart Ehrman, Peter Head, and Adela Collins take the opposite position.Footnote 6

I propose in this study that future editions print Mark 1:1 as Ἀρχὴ τοῦ εὐαγγελίον Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ Υἱοῦ Θεοῦ, “A beginning of the good news about/of Jesus Christ the Son of God.” Thus, the two questionable words are under “partial erasure.”

This article does not propose placing all “dubious” texts under “partial erasure.” The technique is not a panacea solution for all textual problems. Editors should use common sense in dealing with text-critical issues. The study does offer three general principles for editors: 1) make the reader as active in the decision/reading process as possible; 2) do not make the text inaccessible with arcane symbols (critical signs); 3) wake up the reader! Indeed, editors need to shake up readers. The philosopher Martin Heidegger emphasized the need to wake up “being” from her slumber.Footnote 7 The strikethrough of words in the Holy Scripture is like the cut of a knife, threatening the text, perhaps even the reader.

Mark 1:1 in Codex Sinaiticus as a Test Case

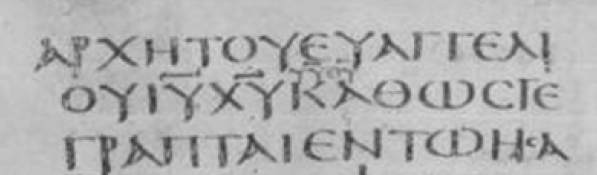

This study does not aim to revisit the whole manuscript evidence to Mark 1:1.Footnote 8 Instead, I will illustrate the topic with evidence from the famous fourth-century Codex Sinaiticus, “the world’s oldest and most complete manuscript of a Greek Bible.”Footnote 9 Due to this codex’s significance and the ambiguous text it represents in Mark 1:1, I have selected the Codex Sinaiticus as a test case for how modern editions could represent textual ambiguities.Footnote 10 Figure 1 reproduces Mark 1:1–2a.

Fig. 1. Codex Sinaiticus. Mark 1:1–2a.

In the second line, above the seventh and the eighth letters, is a tiny addition of four letters: ΥΥ ΘΥ, the abbreviation for Υἱοῦ Θεοῦ, “Son of God.”

©British Library Board (London, British Library, MS 43725; folio: 217b)

The scribe(s) wrote everything in capital letters, as was the custom until the ninth century.Footnote 11 The first line in figure 1 reads: Ἀρχὴ τοῦ εὐαγγελί, “the beginning of the good ne.” The Greek word for “news” continues on the second line. The first six letters of the second line are: ον ΙΥ ΧΥ, “ws about Jesus Christ.” The abbreviation ΙΥ ΧΥ stands for Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ, “Jesus Christ.”

After the letters ΧΥ, the scribe wrote the adverb καθώς, “as,” which is the first word of Mark 1:2: “As it is written in Isaiah the prophet: ‘I will send my messenger ahead of you, who will prepare your way’ ” (NIV).Footnote 12 This second verse introduces us to John the Baptist. Our interest remains on καθώς. Look carefully at the first two letters of this adverb in Sinaiticus (fig. 1). Above them, you see a small addition of four letters: ΥΥ ΘΥ, abbreviations for Υἱοῦ Θεοῦ, “Son of God.”

Who added these four letters? It might have been the same person who copied almost all the New Testament, including the Epistle of Barnabas. The scribe is known as “A.”Footnote 13 Alternatively, scribe “D” is responsible for the addition.Footnote 14 This D is known as the supervisor of the project Codex Sinaiticus.Footnote 15 Scribes A and D were contemporary, and they worked together, “since they take over from each other within a quire, a book, and even a column,” observes Peter Head.Footnote 16

We now have a short and long version of Mark 1:1, one without and one with Υἱοῦ Θεοῦ, “Son of God.” Are these four letters original or a later addition?

According to Adela Yarbro Collins, the reading Υἱοῦ Θεοῦ, “Son of God,” is “most likely secondary, because an accidental omission in the opening words of a work is unlikely.”Footnote 17 In other words, the Vorlage (the manuscript that scribe A or D used as their source) did not contain Υἱοῦ Θεοῦ. Thus, there would have been no error on the part of the scribe of Sinaiticus, and it was the scribe’s “invention” to add these extra words.

Tommy Wasserman argues instead that there was indeed a mistake, that is, the scribe’s Vorlage did have these Greek words.Footnote 18 According to Wasserman, the (supposed) error depended on the homoioteleuton, a term meaning “similar ending.” Homoioteleuton designates a type of error made when a scribe’s eye accidentally skips from one word or letter to the same word or letter later in the line because they look identical. In Mark 1:1, the (alleged) error would have depended on all the abbreviations ending with an upsilon: ΙΥ ΧΥ ΥΥ ΘΥ.Footnote 19

However, Bart Ehrman observes that since the shorter form of Mark 1:1 occurs in such a wide spread of the tradition, we cannot easily explain it away as an accident.Footnote 20 David Parker concurs and comments on the short variant of Mark 1:1 in Sinaiticus: “Did the scribe know the shorter form in his head, and then when checking the manuscript against his exemplar realize he had omitted words present in it, and supplied them? Was the absence of the words noticed in some other way? To be fanciful, did a visitor walk into the scriptorium, glance at a few sheets, and suggest that other copies read ‘son of God’ at the beginning of Mark?”Footnote 21

Messianic Secret

Parker comments on the mystical addition of the phrase Υἱοῦ Θεοῦ, “Son of God,” into Sinaiticus. Indeed, in Mark 1:1, we are facing a mystery, with two Greek words appearing and disappearing in the NT manuscripts. It is possible to associate this enigma with a motif in Mark’s Gospel known as the “messianic secret,” meaning that Mark would have represented Jesus ordering his disciples to be silent about his messianic mission. William Wrede, in 1901, was the first to draw attention to the “messianic secret”.Footnote 22 One key passage is Mark 8:30: ἐπετίμησεν αὐτοῖς ἵνα μηδενὶ λέγωσιν περὶ αὐτοῦ, “Jesus warned them not to tell anyone about him.”

Larry Hurtado has pointed out that “it is very significant that Jesus is called the ‘Son of God’ only by God (1:11, 9:7), by demons (3:11, 5:7), and by one man, the centurion at the cross (15:39), illustrating Mark’s emphasis upon the blindness of people in his own ministry.”Footnote 23 Thus, three categories of beings recognize Jesus’s identity. They have something in common, namely, that they are outsiders who have inside knowledge, as observed by Stephen D. Moore.Footnote 24 Since the demons are opposers to Jesus, they are outsiders. However, they are also insiders because they know who he is.

As for the centurion, as a pagan he is an outsider, but he becomes an insider when he makes his so-called confession at the foot of the cross: Ἀληθῶς οὗτος ὁ ἄνθρωπος νἱοῦ θεοῦ ἦν, “Truly this man was God’s son” (Mark 15:39).Footnote 25 Yet, as Hurtado observes, God’s people, that is, the Jews—the insiders—do not acknowledge that Jesus is God’s son. The Jews are (allegedly) insiders, since they have the scriptures (the Hebrew Bible) and since Jesus performs many miracles among them.Footnote 26

These comments by Hurtado and Moore help us understand the ramifications of including or omitting Υἱοῦ Θεοῦ, “Son of God,” in Mark 1:1: if we keep the phrase, we are like the centurion who recognizes the divine nature of Jesus.Footnote 27 The shorter variant emphasizes the secrecy motif in Mark’s Gospel.

Jesus himself used the word “mystery.” He proclaimed τὸ μνστήριον τῆς βασιλείας τοῦ θεοῦ, “the mystery of the Kingdom of God” (Mark 4:11).Footnote 28 A spiritual mystery depends as much on an absence as on presence.Footnote 29

The French philosopher Jacques Derrida has argued that Western thinking prefers presence to absence.Footnote 30 Instead, we should balance these two concepts—presence and absence. They are not opposites but accomplices of each other.Footnote 31 It is necessary not to suppress or downplay either component in the couple “presence and absence.” In Mark 1:1, the words Υἱοῦ Θεοῦ, “Son of God,” being both present and absent, create a mystical contradiction, in harmony with the themes of Mark’s Gospel: “messianic secret” and the “mystery of the Kingdom of God.”

The Problem with Square Brackets and the Footnote System

Peter Malik observes: “Sinaiticus provides genetic support for both the omission and the inclusion of the title ‘son of God’ in the beginning of Mark’s Gospel. Deciding on which of the two readings is to be preferred, however, is not the matter for our discussion.” Footnote 32

Since Sinaiticus supports both the omission and the inclusion of Υἱοῦ Θεοῦ, “Son of God,” would it not be preferable for editors to display this ambiguity in a way that reaches—through translations—readers of the Bible?

We have seen that the UBS5 Greek New Testament uses square brackets to display the ambiguous nature of Mark 1:1: Ἀρχὴ τοῦ εὐαγγελίον Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ [νἱοῦ θεοῦ]. The question is whether square brackets are the proper way to present the difficulties in that verse. My main argument against them is that translators treat Mark 1:1 as if the square brackets do not exist in the critical editions of the Greek New Testament: all translations (that I have consulted) include the phrase “Son of God” but, at the same time, square brackets are missing.

For instance, the New International Version translates Mark 1:1 as “The beginning of the good news about Jesus the Messiah, the Son of God.” The New Living Translation renders it: “This is the Good News about Jesus the Messiah, the Son of God.” As a third and final example, there is the English Standard Version: “The beginning of the gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God.”Footnote 33

The result is that the reader does not know how uncertain the status of the phrase Υἱοῦ Θεοῦ, “Son of God,” is. The introductory verse to the Gospel is of utmost significance, since it presents the most challenging claim: the protagonist is the Son of God! This affirmation is problematic, as its status among manuscripts is uncertain. The editions display the uncertainty of Υἱοῦ Θεοῦ with square brackets. However, translators ignore them. Therefore, NT editors must find a more efficient way of showing textual ambiguities.

Should translators and editors inform readers about such uncertainties with the use of a footnote? The footnote system would not be sufficient, because many readers would miss “the important variant readings,” observes Eldon Jay Epp.Footnote 34 He continues: “If numerous variants have a story to tell—as they do—their delegation to the footnote style apparatus mutes their voices and suppresses their narratives.”Footnote 35

I propose in this article a more efficient way of treating problems like that of Mark 1:1. The idea draws inspiration from the philosophers Martin Heidegger and Jacques Derrida.

Sous Rature

The German philosopher Martin Heidegger placed the term “being” (Sein) under erasure by placing an X over it. Although partially erased, the word remains visible.Footnote 36 Jacques Derrida, too, used the “under erasure” technique, as seen in the quotation below. Thanks to Derrida, this technique is better known under its French name: sous rature. In fact, he popularized it.Footnote 37

… the question of essence, to the “ti esti.” The “formal essence” of the sign can only be determined in terms of presence. One cannot get around that response, except by challenging the very form of the question and beginning to think that the sign is that ill-named thing, the only one, that escapes the instituting question of philosophy: “what is … ?”Footnote 38

The literary critic Gayatri Spivak explains why Heidegger and Derrida placed certain words under erasure: “In examining familiar things, we come to such unfamiliar conclusions that our very language is twisted and bent even as it guides us. Writing ‘under erasure’ is the mark of this contortion.”Footnote 39 According to Heidegger, a word’s current and metaphorical meanings can mislead us. The X-sign is a call to return to etymology. Being speaks to us through language, which is entangled with the world and its history.Footnote 40

Heidegger explains: “The crossing out of this word initially has only a preventive role, namely, that of preventing the almost ineradicable habit of representing ‘being’ as something standing somewhere on its own that then on occasion first comes face-to-face with human beings.”Footnote 41 He continues: “the sign of this crossing through cannot, however, be the merely negative sign of a crossing out. It points, rather, toward the four regions of the fourfold and their being gathered in the locale of this crossing through.”Footnote 42 Thus, the X evokes the four regions of the quadrant, intersecting in the middle of being (us).Footnote 43 The crossing over of “being” shows that we are, or should be, in the world.

When Derrida places the X over the French verb est (is), he criticizes the Western preference for presence. Derrida’s X-sign partially cancels “presence” to reveal its opposite.Footnote 44

The erasure technique can provide guidance when we edit the Greek New Testament. For example, when we encounter questionable words, such as Υἱοῦ Θεοῦ, “Son of God,” in Mark 1:1, we could use the X-type of cancellation. Instead, I propose that we draw a continuous line through them: Υἱοῦ Θεοῦ.Footnote 45 This strikethrough pays homage to another device Heidegger used, which is the extra hyphen that he sometimes added to words such as Dasein, spelling it Da-sein. In everyday German, the noun means “existence.” Taylor Carman explains that Dasein “denotes a human being’s existence, or one’s ‘living’ or ‘daily bread.’ Heidegger uses the term to refer to an individual human being.”Footnote 46

Heidegger did not invent a new meaning for Dasein. Instead, he believed that he revived its original sense, which is “being there.”Footnote 47 Da is an adverb meaning “there,” and sein means “being.” By adding the hyphen, the philosopher brought attention to the prefix, da.

The hyphen in Da-sein has many meanings. The German term for “hyphen” is Bindestrich, coming from binden, “to join,” and Strich, meaning “line.” Metaphorically speaking, the hyphen in Da-sein is a line or a path that joins humans to the world.

The Strich (line) relates to “reading.” Heidegger points out that the original meaning of lesen (reading) is “to collect” or “to gather.”Footnote 48 Sarah Pourciau explains that, in Heidegger, Strich designates the path that the primordial reader-gatherer followed.Footnote 49 Thus, Heidegger associates written signs with the “physical landscape of hunting and gathering out of which they are presumed to have emerged,” concludes Pourciau.Footnote 50

The hyphen in Da-sein also shows a lack of relationship to the world. Ivo De Gennaro aptly comments: “the hyphen is not a punctuation mark used to divide two syllables or word elements. Rather, the hyphen is the cut (or schism) itself.”Footnote 51 So, in De Gennaro’s interpretation, the hyphen in Heidegger’s Da-sein represents our unfortunate and violent separation from the world.

In other words, the hyphen in Da-sein is paradoxical: it is both a lifeline and a cut; it is a desire of bringing the being into the world but also an acknowledgment of her deplorable distancing from it.Footnote 52

In the term Da-sein, the prefix da (there) represents the object (the cosmos), while the sein (being) is the subject (the “I”). Thus, the hyphen separates and joins the subject and the object.

Heidegger hyphenated other words as well, such as Er-eignis and Ab-grund. Frank Schalow comments: “By hyphenating these words, Heidegger assigns an independent status to the prefixes…. He thereby leads us into the space of freedom, which remains inaccessible through the simple use of a dictionary.”Footnote 53 Indeed, the hyphen also symbolizes freedom.

The strikethrough in Υἱοῦ Θεοῦ, “Son of God,” is the multiplied hyphen that joins and cuts. The method of partial cancellation restores freedom to the reader; instead of the editor or the translator making a choice, you (the reader) now have the power to keep these words or eliminate them.

The strikethrough pays homage to two philosophical methods: the X-sign of partial cancellation and the hyphen in words such as Da-sein. Their common denominator is that they unite and separate. But, most significantly, the partial cancellation and the hyphen restore freedom to the Da-sein (us), the liberty to cut or restore.

In other words, the term Da-sein/Dasein describes who we are and explains our relationship to the world. Mark 1:1, in turn, describes who Jesus Christ is. The appearance and disappearance of Υἱοῦ Θεοῦ, “Son of God,” makes us reflect on Christ’s identity and his relationship to us. The strikethrough over this phrase represents the divine mystery that we can never wholly understand (Mark 4:11).

Clearing: A Place of Concealing and Lightening

For the sake of argument, suppose now that the scribe of Codex Sinaiticus was only absentminded. In Mark 1:1, he or she made an error and corrected it. Even so, we should signal it in an edition and translation since “error is not just accidental but belongs to the very essence of truth as unconcealment,” as the American philosopher Graham Harman says.Footnote 54

It is my hope that future editions will print Mark 1:1 as Ἀρχὴ τοῦ εὐαγγελίον Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ Υἱοῦ Θεοῦ, “A beginning of the good news about/of Jesus Christ the Son of God.” This procedure would be truthful to the manuscript evidence, which shows that the last two words are questionable.Footnote 55

The partial cancellation aims to bring forth the idea that truth is a process of continuous unconcealment and hiding. Heidegger writes:

The “Being-true” of the λόγος [word] as ἀληθεύειν [to speak truly] means that in λέγειν [to speak] as ἀποφαίνεισθαι [make known], the entities of which one is talking must be taken out of their hiddenness; one must let them be seen as something unhidden (ἀληθές); that is, they must be discovered. Similarly, “being false” (ψεύδεσθαι) amounts to deceiving in the sense of covering up [verdecken].Footnote 56

Heidegger compares the concept of truth with a clearing, in German Lichtung. Inwood comments: “Lichtung and lichten stem from Licht, ‘light,’ but have since lost this link and mean, in standard usage, a ‘clearing, glade’ in a forest and ‘to clear’ an area. Heidegger restores their association with light, so that they mean, ‘light(en)ing; light(en).’ His use of the terms is influenced by Plato’s story of prisoners in a cave.”Footnote 57 Inwood adds: “Being is lightened and concealed. Being lightens and conceals, both itself and entities.”Footnote 58

The gesture of striking through words is like cutting down trees: both cases have the unexpected effect of bringing forth light. The clearing becomes a brighter place when the trees disappear. Yet, this same process hides/destroys the trees. Revelation means disappearance.

Distancing from Textual Conventions

Would it not suffice that Bible translations alone use the “under erasure” technique?

One might argue that scholars who have been trained to use the Greek New Testament editions understand the complexity of the transmission of the NT text. However, the epigraph that introduces this article—a quotation from James Rendel Harris—suggests that no one can grasp its complexity.Footnote 59 But for the sake of argument, let us suppose that textual critics possess this ability. If so, why change textual conventions and symbols such as the use of square brackets?

One could furthermore affirm that the more pressing problem is the translations that obscure variation by printing rarely consulted footnotes that share no information about the extent of the variation that is flagged.

However, the translations are only the symptom. The root of the evil is the editions. Jennifer Knust comments that the custom of bracketing beloved texts is “a fitting material symbol of what it has meant to produce a ‘modern text,’ a visible proof of a willingness to embrace the secular distancing modern criticism demands.”Footnote 60

In other words, editors began to place certain cherished text passages, but not necessarily “original,” within square brackets to have more distance from them. At a distance, editors and readers could, supposedly, better observe and judge the texts placed between square brackets. However, as Yii-Jan Lin has observed, “the clinical distance textual critics maintain from their work is a fiction.”Footnote 61

Yet, one might instead ask if textual critics should keep a distance in the first place. Looking at things from afar makes them unreal and dim. Heidegger warns against the danger of distancing: “remoteness, like distance, is a determinate categorial characteristic of entities whose nature is not that of Dasein [human being].”Footnote 62 He compares the idea to wearing glasses: when “a man wears a pair of spectacles which are so close to him distantially that they are ‘sitting on his nose,’ they are environmentally more remote from him than the picture on the opposite wall.”Footnote 63

To illustrate the idea of “real” space and its relationship to us, Heidegger introduces the concepts zuhanden (ready-at-hand) and vorhanden (presence-at-hand). Inwood explains: “Zuhanden, literally ‘to, towards, the hands,’ is now, unlike vorhanden, not a common word. It is used in such phrases as ‘for the attention of [zuhanden] so-and-so.’ Again, Heidegger breathes new life into the word and applies it to things that serve human purposes in some way: articles of use, raw material, footpaths, etc.”Footnote 64

As for vorhanden, it literally means “before the hands, at hand”. The extended meaning is “available,” “existing”—both in everyday German and in Heidegger’s usage.Footnote 65 Things are vorhanden (existing), for instance, for a scientist looking at them from an emotional distance. Broken artifacts are also vorhanden.Footnote 66

Spectacles—that you wear—are “ready-at-hand” (zuhanden) because they are a useful item that you hardly observe. They are a part of you, an extension of you. However, they become vorhanden (presence-at-hand) when they break. You observe the broken glasses from a distance.Footnote 67

We can compare the damaged glasses with the text “under erasure.” Both are “broken” and thus at a distance. However, you can heal the text by discarding the partial cancellation. If so, the text is close—zuhanden. You can also reject the text, which then becomes vorhanden.

On the other hand, text within square brackets is permanently at a distance since the editorial committee has decided for you that the text is “unreliable.”Footnote 68

Text within square brackets gives the impression that you do not have any control. On the other hand, the text under partial erasure is controllable, being both close and at a distance; both healed and broken; both “ready-at-hand” and “presence-at-hand”; both “so secret and so close.”Footnote 69

If you are an editor of the Greek New Testament, you might ask if you should apply the “under erasure” technique to all text currently between square brackets. The answer is affirmative. The same goes also to double square brackets. They “enclose passages which are regarded as later additions to the text, but which are of evident antiquity and importance.”Footnote 70 The UBS5 places Mark 16:9–20, for instance, within double square brackets.Footnote 71 Compared with single square brackets, double ones are a further step away from the world where being belongs; the double square brackets create a second wall of defense against a possible intrusion from the reader. Consequently, editors should avoid the double square brackets as well.

What hinders editors from placing texts, such as Mark 16:9–20, under partial erasure?

Besides the single and double square brackets, the UBS5 Greek New Testament uses many other symbols to indicate textual problems. All these symbols serve to distance the reader from the text. Editors should therefore shun them.

I do not propose placing all “dubious” text under “partial erasure.” The technique is not a panacea solution for all textual problems.Footnote 72 Editors should use common sense in dealing with text-critical issues. However, editors do need to shake up readers. Heidegger emphasized the need to wake up “being” from her slumber.Footnote 73

Editors should throw away their bracketing habits. This habit is dangerous because it makes readers passive; it gives the impression that the text is far away, that it is beyond their control. Instead, the partial erasure technique helps expel indifference and, we hope, elicits a visceral reaction in the reader.

Spivak explains her role: “My peculiar theme is always persistent critique.”Footnote 74 She focuses “on different elements in the incessant process of re-coding that shifts the balance of the pharmakon’s effect from medicine to poison.”Footnote 75 Tat-Siong Benny Liew affirms the need for a “persistent critique,” which must be “a negation of positives, a constant challenge to closure.”Footnote 76 An example of a closure can be the square brackets that close the text, making a barrier around it.

How can Bible readers become persistent critics when the editors have already made all the decisions for them and closed the text to intervention?

Conclusion

Derrida has argued that Western thinking prefers presence to absence. Instead, it is healthier to balance these two concepts—presence and absence. Thus, scholars working with new editions of the New Testament should remember that their preference for presence or absence of the phrase Υἱοῦ Θεοῦ, “Son of God,” will create an unfair imbalance. The evidence from paleography shows that the words Υἱοῦ Θεοῦ are both absent and present. A way to communicate this ambiguity for readers is to place them under partial erasure: Υἱοῦ Θεοῦ.

Present editions place this phrase within square brackets. The rationale for this procedure is highly dubious, since it creates distance to texts placed within them. As Heidegger has argued, “remoteness, like distance,” is not characteristic of the human being. On the other hand, a text under partial erasure is both close and at a distance. Texts under partial erasure are both dead and living, while texts in square brackets are only far away—dim. Such texts encourage passivity in the reader.

What is the final message to editors? Heidegger compared truth to the process of creating a clearing, in German, Lichtung. Cutting down trees is destructive but subsequently allows the appearance of light. However, leaving a forest intact also has an obvious advantage.

As for the Bible text, if you, as an editor, place it within square brackets, readers will see the text dimly, like you would see a forest from afar. If you strike through it, you are in the process of cutting it down. Here, readers step in by becoming fellow lumberjacks. They can help you cut down the trees (the text). Alternatively, readers can decide to leave the forest intact. Thus, may editors turn into lumberjacks but let the readers decide if they want to become fellow lumberjacks or tree saviors.