Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 June 2011

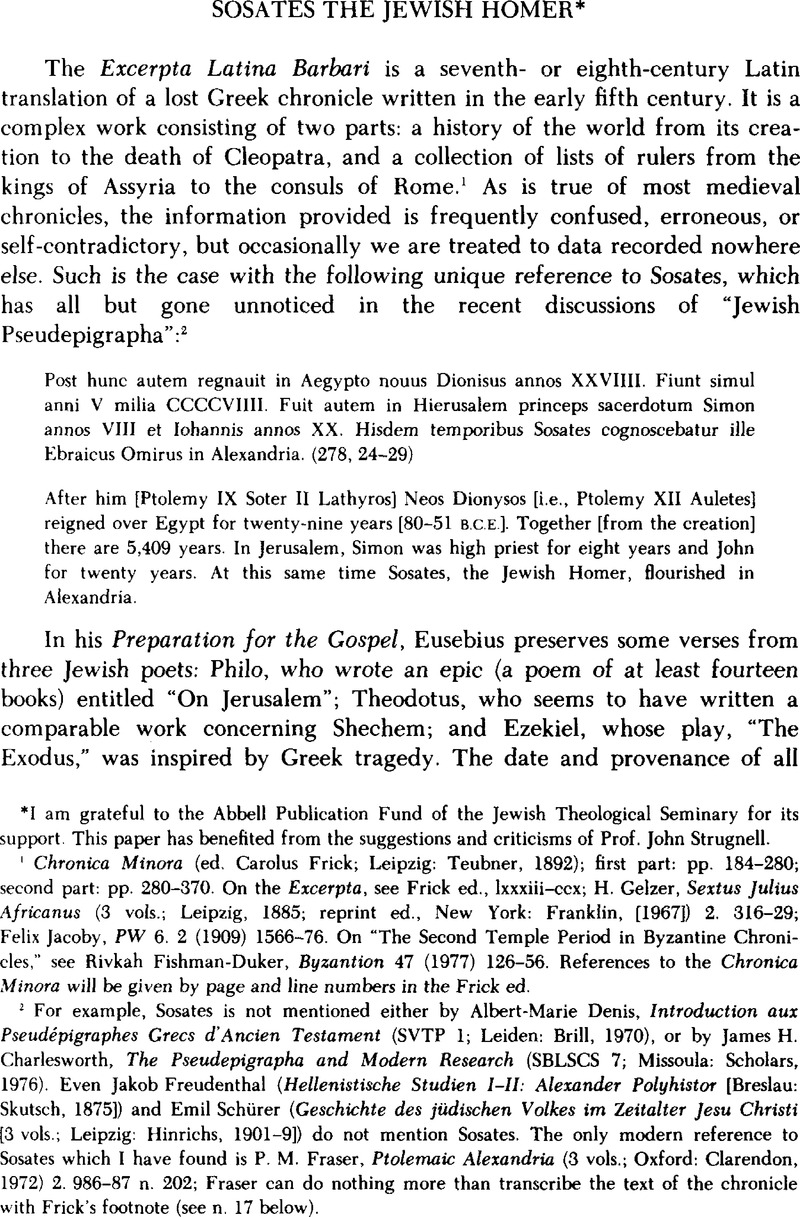

1 Chronica Minora (ed. Carolus Frick; Leipzig: Teubner, 1892); first part: pp. 184–280; second part: pp. 280–370. On the Excerpta, see Frick ed., lxxxiii-ccx; Gelzer, H., Sextus Julius Africanus (3 vols.; Leipzig, 1885Google Scholar; reprint ed., New York: Franklin, [1967]) 2. 316–29; Jacoby, Felix, PW 6. 2 (1909) 1566–76Google Scholar. On “The Second Temple Period in Byzantine Chronicles,” see Fishman-Duker, Rivkah, Byzantion 47 (1977) 126–56Google Scholar. References to the Chronica Minora will be given by page and line numbers in the Frick ed.

2 For example, Sosates is not mentioned either by Denis, Albert-Marie, Introduction aux Pseudépigraphes Grecs d'Ancien Testament (SVTP 1; Leiden: Brill, 1970)Google Scholar, or by James H. Charlesworth, The Pseudepigrapha and Modern Research (SBLSCS 7; Missoula: Scholars, 1976). Even Jakob Freudenthal (Hellenistische Studien l-ll: Alexander Polyhistor [Breslau: Skutsch, 1875]) and Emil Schurer (Geschichte des judischen Volkes im Zeitalter Jesu Christi [3 vols.; Leipzig: Hinrichs, 1901–9]) do not mention Sosates. The only modern reference to Sosates which I have found is Fraser, P. M., Ptolemaic Alexandria (3 vols.; Oxford: Clarendon, 1972) 2. 986–87 nGoogle Scholar. 202; Fraser can do nothing more than transcribe the text of the chronicle with Frick's footnote (see n. 17 below).

3 For the fragments, see Denis, Albert-Marie, Fragmenta Pseudepigraphorum quae Supersunt Graeca (PVTG 3; Leiden: Brill, 1970) 203–16Google Scholar. For the provenance and date of these authors, see Denis, Introduction, 270–77. It is usually said that Philo, Theodotus, and Ezekiel hail from Jerusalem, Samaria, and Alexandria respectively, but I prefer to admit that the provenance of these authors is unknown. On Theodotus see Collins, John J., “The Epic of Theodotus and the Hellenism of the Hasmoneans,” HTR 73 (1980) 91–104Google Scholar. On Alexander Polyhistor, see Stern, Menahem, Greek and Latin Authors on Jews and Judaism (Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Arts and Sciences, 1974) 157–64Google Scholar. On his date, see Jacoby, Felix, Die Fragmente der griechischen Historiker Ilia (reprint ed.; Leiden: Brill, 1964) 248–50Google Scholar (introduction to no 273).

4 The name Sosates (Σωσάτηϛ) is rare for either pagan or Jew and may be corrupt; Fraser calls it “improbable.” It appears neither in the prosopographic indices to the Corpus Papyrorum Judaicarum (ed. Victor Tcherikover et al.; 3 vols.; Cambridge: Harvard University, 1957–64), nor in Preisigke, F., Namenbuch (Heidelberg, 1922)Google Scholar, nor in Pape, W. and Benseler, Gustav, Handwörterbuch der griechischen Sprache III: Wörterbuch der griechischen Eigennamen (3d ed.; Braunschweig: Vieweg, 1884)Google Scholar. D. Foraboschi (Onomasticon Alterum Papyrologicum: Supplemento al Namenbuch di F. Preisigke [Testi e Documenti 16; Milan: Istituto Editoriale Cisalpino, 1971] 297) lists a Σoυσαίτηϛ from a seventh-century ostracon (O. Edfou 213). Pape and Benseler list Σωσάδηϛ, Σωσιάδηϛ Σωτάδηϛ.

5 Cognoscebatur = γνωριζεται= floruit indicates either the fortieth year of the subject's life or the date of some noteworthy accomplishment. See Erwin Rhode, Kleine Schriften (2 vols.; Tübingen: Mohr, 1901) 1. 136–40.

6 It makes little difference here whether “the author” is the author of the Greek original of the Excerpta, his source (“the Alexandrian chronicle”; see Frick ed., lxxxix-clxxi), or his sources source (Julius Africanus?).

7 I have maintained the chronicle's spelling of the high priests and kings. I have introduced the numeration of the high priests in list A; the chronicle itself numbers those of list B. For the period of the Persian kings and Alexander the Great (high priests 1–6), the first part of the chronicle is somewhat detailed, mentioning several political events and many writers and philosophers. For the Ptolemaic period (high priests 7-end) it is much thinner, mentioning only those names and events that I have indicated.

8 I have maintained the chronicle's spelling of the names of the high priests and kings. I have introduced the numeration of the high priests in list A; the chronicle itself numbers those of list B. For the period of the Persian kings and Alexander the Great (high priests 1–6), the first part of the chronicle is somewhat detailed, mentioning several political events and many writers and philosophers. For the Ptolemaic period (high priests 7-end) it is much thinner, mentioning only those names and events that I have indicated.

9 Gelzer, Julius Africanus, 174, and Frick ed., clxv. Instead of Iohannes (no. 5), Eusebius has lonathes. On the great influence exercised by Eusebius's list, see Gelzer, Julius Africanus, 170–76.

10 The additions to numbers 9 (“filius Simoni frater Eleazari”) and 10 (“filius Iaddi”) indicate that the author was familiar with a non-Eusebian tradition.

11 If we delete one accidental duplication (Iaddus no. 8 and Onias no. 9 duplicate Iaddus no. 6 and Ianneus [= Onias] no. 7) and allow for a few other mistakes (the chronicle has Iodae no. 5 instead of Ioannes; Ianneus no. 7 instead of Onias; Ianneus no. 18 instead of Ioanthes), this list is identical with that of codex Parisinus 1773 as given by Gelzer, Julius Africanus, 175. Gelzer did not realize that the Excerpta contains two different lists of high priests.

12 The intended identification of numbers 19 and 20 is made certain by comparison with list B and cod. Parisinus 1773. On the confusion Ianneus-Ionathes, cf. n. 11.

13 The synchronization of Ben Sira with Iaddus no. 8 clearly is secondary since that high priest is a product of accidental duplication; see n. 11.

14 This is in striking contrast to the previous lists used by the author which regularly mention literary and political figures. See n. 7.

15 On Egypt under Auletes, see Will, Eduard, Histoire politique du monde hellenistique (Annales de lEst 32; 2 vols.; Nancy: Universite de Nancy, 1967) 2. 437–45Google Scholar. The Jewish garrison at Pelusium allowed the Romans to reinstate Auletes.

16 Perhaps a contemporary of Theodotus, Ezekiel, and Aristeas; certainly a contemporary of Lysimachus, the translator of the Greek Esther.

17 Historical epics were written at various royal courts during the Hellenistic period, although not at Alexandria. See Fraser, Ptolemaic Alexandria, 2. 883 n. 58. I refrain from indulging in further speculation on the content of Sosates' work. Wachsmuth apud Frick ed. suggests that Sosates wrote a Homeric summary of biblical history, while A. Schoene (in Gott. gelehrte Anzeigen [1875] 1501–2, referred to by Frick) flirts with the idea that Sosates wrote the Pseudo-Phocylidea (but why should a gnomic poet be called a Homer?).

18 (1) is implausible because a list which did not mention Callimachus, Theocritus, Eratosthenes, etc., presumably did not mention the obscure Sosates. (3) is not as plausible as (2) because the author had no reason to attempt to “correct” the dating of Sosates, who was far less important and far less significant than the LXX, Ben Sira, and the Maccabees.

19 “Iosephus, Graecus Livius,” Jerome, Ep. 22 (ad Eustochium) 35. 8.