1. Background and scope

Sweden's response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has evoked strong national and international reactions. The response has been characterized by the use of voluntary measures emphasizing individual responsibility and aiming to mitigate rather than suppress the spread of COVID-19. Important policy goals have been to secure health care system capacity, protect high-risk groups and ensure that measures are implemented at the right time to alleviate the impact on individuals and businesses, and ensure sustainability over time (Government Offices, 2020h). Although Sweden has experienced relatively low per-capita mortality rates compared to countries such as Belgium and the UK, mortality rates are far higher than that in neighboring Nordic countries. This may partly be explained by the higher incidence of international travel in Sweden in February and March 2020, but the question remains whether the reliance on voluntary measures, particularly in the early phases, played a role in the higher excess mortality rates as compared to the Nordic neighbors. International experts and media have questioned the Swedish strategy which they believed relied too much on voluntary measures and ‘soft’ restrictions. Critics have argued that the ‘Swedish experiment’ was a failure and that the government needed to be more active in curbing the infection and stop ‘hiding’ behind its authorities (see Irwin, Reference Irwin2020). Swedish representatives have, however, argued that the Swedish response was not that different from other western countries (Tegnell, Reference Tegnell2021).

The nature of the pandemic and the Swedish policy response has changed over time, and the question remains whether it is as different as some have argued. The purpose of this paper is thus to describe Sweden's response to COVID-19, and investigate how it has changed during the three waves of the pandemic occurred from March 2020 to June 2021. We begin by describing the progression of the pandemic in Sweden and the institutional basis for the Swedish response. Thereafter, we review the policy response and how it evolved, and how providers of health- and elder care have responded to the crisis. We do not aim to exhaustively catalog every measure taken as part of the policy response or evaluate its effects on public health and society, but rather to describe its central characteristics through an analysis of official documents, public inquiries, reports, debate- and news articles and scientific studies.

1.1 Progression of the pandemic in Sweden

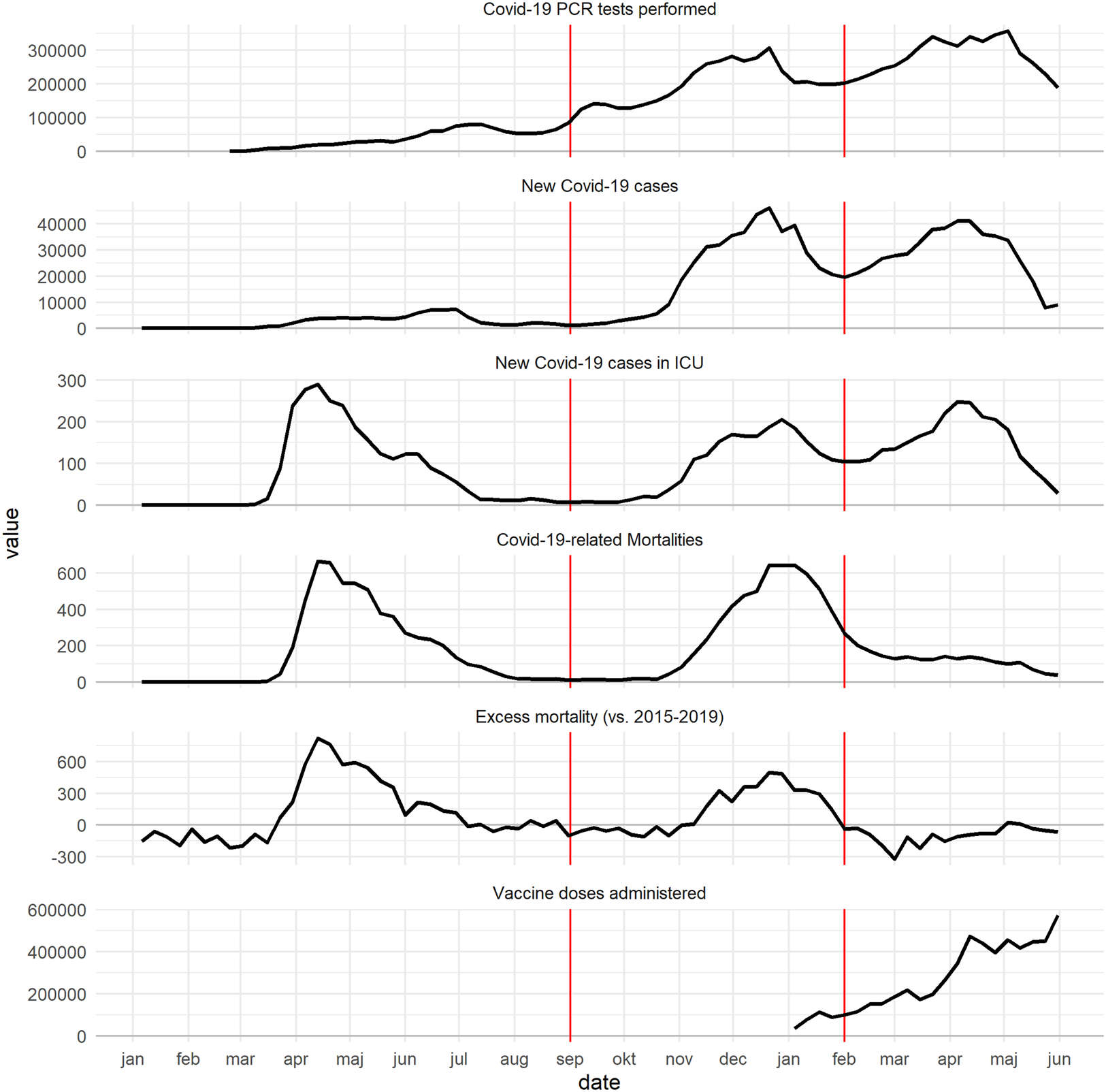

The first case of COVID-19 in Sweden was identified in late January 2020, but the sustained community transmission of the disease within the country did not begin until early March 2020, initially most heavily impacting Stockholm and adjacent regions (PHA, 2020a). By mid-April 2020, the first wave of COVID-19 had reached a peak in many regions across the country, with the number of weekly cases averaging 4000 over a sustained period of time, and the number of weekly deaths peaking at 658. In mid-June 2020, an apparent increase in the number of cases occurred, although this increase in the number of positive cases likely stemmed at least in part from changes in the Swedish testing strategy as discussed later.

Over the summer of 2020, the number of new cases stabilized at ca. 2000 per week, whereas COVID-related deaths steadily declined. By September 2020 however, the number of cases again began to increase, marking the beginning of a second wave of the pandemic in Sweden. By November 2020, infection rates had exceeded peak rates during the first wave, with the peak of the second wave occurring at the end of the year. Overall testing rates during the second wave far outstripped those during the first, with testing increasingly distributed across the general population.

After declining over the course of January 2021, COVID-19 incidence and intensive care admission rates again began to increase in February 2021, marking the beginning of a third wave. Vaccine administration began in January 2021 and gradually ramped up over the course of the third wave to the delivery of ca. 600,000 weekly doses during the month of June. Unlike the previous two waves, since February 2021 mortality rates have remained low, with mortality rates consistently below the 2015–2019 average despite disease incidence and intensive care unit (ICU) admission rates similar to previous waves. The progression of the COVID-19 pandemic and the delineation of these three waves of the pandemic for the purposes of this study is described in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Summary of the weekly data made available by Swedish agencies regarding COVID-19. Red vertical lines denote the delin eation of the three waves as discussed in this paper. Mortality data are truncated to avoid under-reporting of recent weeks. See Supplementary data files stored at Mendelay Data (Spangler, 2021).

1.2 Institutional basis for the Swedish response

In order to understand the Swedish response, it is necessary to understand the institutional context and conditions. The first of these conditions is Sweden's existent legal framework. The Swedish constitution does not allow for restrictions on internal freedom of movement for individuals as required to execute the type of mandatory ‘lockdowns’ (i.e. restrictions on individuals leaving their homes) found in other countries. Sweden furthermore lacks the possibility to declare ‘state of emergency' during peacetime (Jonung, Reference Jonung2020). The two laws which formed the primary legal basis for the responses described in the following sections were rather the Infectious Diseases Act (2004:168) (Smittskyddslagen) and the Public Order Act (1993:1617) (Ordningslagen). The Infectious Diseases Act enables extraordinary measures to be taken by government agencies and regional health care systems to prevent the spread of diseases dangerous to society (samhällsfarliga sjukdomar), including by quarantine and isolation of infected individuals, and health screenings on arrival in Sweden. COVID-19 received this designation at the beginning of February 2020. A central premise of the law is each person's legal responsibility to take actions necessary to protect others from the risk of infection. The Public Order Act meanwhile regulates public gatherings and events such as concerts, sport events, and demonstrations and has formed the basis for limitations on public gatherings. Measures enacted by Swedish authorities related to restricting individual freedom of movement beyond the specific settings enumerated in these laws can thus only be based on voluntary compliance.

During the fall of 2020, the government began work on a new permanent pandemic law which would allow for more far-reaching restrictions. Under pressure from the second wave of the pandemic meanwhile, the government proposed a temporary pandemic law. This law broadened the ability of the government and authorities to take measures to slow the spread of infection including by placing limits on a larger range of businesses in terms of simultaneous customers and business hours, and strengthened the ability to limit the size of public gatherings. The temporary law entered into force on the 10th of January 2021, and is valid until the end of September 2021, but may be extended in the case of continued necessity (Government Offices, 2021a). Using this temporary law, the Swedish government was able to enforce broader social distancing measures during the second and third waves of the pandemic.

Another crucial institutional condition shaping the Swedish response was the prominent role of expert agencies. The Swedish constitution guarantees the independence of government agencies, and prevents government officials from interfering in the daily work of the agencies. The Swedish government has thus relied heavily on expert agencies throughout the pandemic. Agencies with a primary responsibility for handling COVID-19 were the Public Health Authority (PHA) and the National Board of Health and Welfare (NBHW). The PHA had a particularly central role, and staff epidemiologists have guided its evidence-based approach. The agency's broad mission pertaining to both disease control and public health has also put the public health perspective at the core of the response, stressing that infection control measures must be balanced with efforts to maintain the mental and physical well-being of the entire population over time. The PHA's role has been coordinative, seeking to provide guidance and assistance to the government and other actors responsible for developing and executing more direct interventions. The PHA has also issued guidelines (Allmänna råd), recommendations (rekommendationer), and regulations (Föreskrifter) directed to the public and community in order to prevent the spread of COVID-19. The bulk of these measures have been voluntary in nature, with the agency stressing that the measures taken in response to the pandemic should be designed for sustainability over a long timeframe (Government Offices, 2020h).

A final institutional condition shaping the Swedish response is the decentralized, multi-level governance model which entails that responsibility for providing health- and social care is divided between the national government, the 21 regions primarily responsible for health care, and the 290 municipalities responsible for social care. Regions are largely autonomous with regard to health care delivery, and each has an infectious disease unit led by a chief medical officer with the operative responsibility within their region. This model sets limits to how direct national-level governance can be, and the COVID-19 response reflects the traditional relationship between the national government and the regions built on mutual trust, dialog, negotiation and a strong focus on ‘soft law’ (Fredriksson et al., Reference Fredriksson, Blomqvist and Winblad2012). This entails specific challenges, requiring substantial collaboration and trust between actors at multiple governmental levels in handling the pandemic.

The Swedish response is perhaps best understood in light of these three crucial institutional conditions: The legal framework, the independence of expert agencies and the decentralized health- and social care system. It is suggested that these factors explain much of the discrepancy between the Swedish response and that found in other European nations. In the following sections, we describe the Swedish policy response with regard to the general public and community as well as the health care system.

2. Responses directed to the public and the community

This section describes central guidelines, recommendations and regulations directed to the public and community actors (e.g. businesses, schools, non-profit associations, etc.), and specifically the elderly population, and how they changed between the three waves.

2.1 Responses during the first wave

2.1.1 General population and community

The public face of the response during the first wave was primarily Sweden's expert agencies, whose representatives communicated regularly with the public through press conferences several times a week and interviews in media. As the spread of infection started to increase in March 2020, the PHA developed guidelines and regulations to prevent the spread of COVID-19 based on the Communicable Diseases Act. The guidelines emphasized individual responsibility in practicing social distancing, hand washing and staying home when ill, which formed the core message delivered to the public throughout the pandemic (HSLF-FS 2020:12). Staying home with even mild symptoms was incentivized through a temporary relaxation of regulations regarding sick-leave benefits (Government Offices, 2020a). Individuals in risk groups who could not work from home were also provided an extended right to sick leave as a preventative measure. A recommendation to avoid unnecessary travel within Sweden was issued in March 2020 (PHA, 2020d). Notably, the PHA did not recommend the use of face masks for the general public, citing unclear evidence and potential detrimental effects such as inducing a false sense of security (PHA, 2020j).

Restrictions on public gatherings were introduced early in the pandemic. On 12th March 2020, public gatherings and events with more than 500 people were banned, which was lowered to 50 people on 29th March 2020 (Government Offices, 2020f). Public transport, shopping centers and other public places were expected to take measures to prevent the spread of infection, for instance by preventing crowding (PHA, 2020f). On 24th March 2020, the PHA issued specific regulations for restaurants, bars and cafes requiring measures to reduce the risk of infection such as only serving patrons seated at tables (PHA, 2020e). Notably, these restrictions were aimed at organizations rather than individuals. From June 2020 onward, amendments began to be made aiming to ease restrictions as it appeared that the peak of the first wave had passed. One of the first changes was the repeal of the recommendation to avoid all unnecessary travel within Sweden, replacing it with a recommendation to avoid public modes of transport on 13th June 2020 (PHA, 2020h).

All employers were urged to enable employees to work from home, and the Government recommended all universities, colleges and upper secondary schools to switch to remote lessons on 18th March 2020 (Government Offices, 2020c). On 21st March 2020, a new law entered into force allowing the temporary closure of elementary- and preschools if deemed necessary (Government Offices, 2020d). This law has, however, not yet been used and schools have largely been kept open, as schools are considered crucial to the wellbeing of young people in the short and long term (PHA, 2020o). However, children and teachers showing any signs of infection have been urged to stay at home. The PHA withdrew the recommendation for remote education in upper secondary schools on 15th June 2020, as children and young people were not considered to be the main drivers of the spread of COVID-19 (PHA, 2020g).

2.1.2 The elderly

Specific guidelines for those over 70 years of age were announced on 16th March 2020 which advised the elderly to limit social contacts, including avoidance of public transport, shops and other public places. Family and neighbors were urged to help the elderly with food shopping or other errands (PHA, 2020c). A national ban on visitors in nursing homes was implemented on 1st April 2020 in response to the spread of the virus in these facilities (Government Offices, 2020g).

2.2 Responses during the second wave

2.2.1 General population and community

On 1st September 2020, the PHA presented an analysis of scenarios for the development of the pandemic during the fall, reiterating that the earlier recommendations regarding self-isolation when ill, social distancing and hand hygiene would remain core elements of the response (PHA, 2020k). The scenario considered to be most likely was a relatively low level of general disease transmission combined with localized outbreaks. The PHA thus sought to rapidly contain such outbreaks through the deployment of regional testing- and contact tracing capacity (PHA, 2020l). As the national strategy shifted toward containing local outbreaks of COVID-19, the PHA opened up the possibility for regional medical officers to supplement national recommendations with more restrictive time-limited local guidelines within a region or a part of a region if necessary (PHA, 2020m).

By the end of October 2020, it was clear that COVID-19 was spreading rapidly throughout Sweden, and by November 2020, all regions had adopted additional local guidelines. In response to concerns that the measures taken in the regions might not be sufficient to reverse this general trend, further mandatory national measures were introduced by the government during November 2020. On 20th November 2020, a ban on serving alcohol after 10 pm entered into force (Government Offices, 2020j). On 24th November 2020, further restrictions were introduced on public gatherings and events based on the Public Order Act, limiting the size of all public gatherings to eight people from the previous limit of 50. These restrictions could only be applied legally to public gatherings such as sporting events and concerts (Government Offices, 2020l). It was, however, encouraged by the authorities in that individuals should also limit the size of private gatherings. In addition to these changes, the prime minister held one of his speeches during the pandemic encouraging the public to take personal responsibility in reducing the spread of COVID-19 (Government Offices, 2020m).

Prior to the winter holidays, the PHA reinforced existing national regulations and general guidelines for the public. It was for instance underlined that everyone should limit their personal contacts and avoid places such as shops and public transport during congestion (HSLF-FS 2020:80). These came into force on 14th December 2020 and to inform the public, a mass SMS was sent on the same day (PHA, 2020p). A few days later, the government and the PHA presented further national regulations including restrictions on the sale of alcohol after 8 pm, and a reduction of the maximum party size at restaurants from eight to four people (Government Offices, 2020o). Based on the temporary pandemic law that entered into force 10th January restrictions were issued to limit the number of simultaneous customers to one per 10 m2 of floor space for gyms, stores and shopping centers (HSLF-FS 2021:2).

Recommendations regarding the use of face masks received renewed attention during the second wave, and in December 2020 the PHA recommended the use of face masks in public transportation during rush hours beginning on 7th January 2021 (PHA, 2020q). Individual regions could also recommend the use of face masks in further settings. Most regions adopted more extensive recommendations, typically involving the use of face masks in unavoidable crowded indoor situations, for example in certain workplaces including elder care settings and stores.

During the second wave, elementary schools and preschools remained open, although there have been different examples of schools closing temporarily due to COVID-19 (SVT, 2020b). Upper secondary schools started to practice remote education again during the fall of 2020 and in January 2021, the government allowed middle schools to employ remote education as well (Government Offices, 2021b).

2.2.2 The elderly

Contrasting with the stricter overall measures during the second wave, specific restrictions relating to the elderly were relaxed. In response to concerns over increased psychological distress and loneliness (PHA, 2020n), specific guidelines applying to those over 70 were repealed on 22nd October 2020, making restrictions uniform across all age groups. The ban on visiting nursing homes was also lifted in the beginning of October 2020, and since then, local recommendations have been issued by various regions and municipalities regarding how visits should be managed at nursing homes. For example, in some regions the use of face masks and outdoor visits have been recommended for visitors (DN, 2020b). As disease spread increased over the fall, regulations were adopted allowing the PHA to implement local nursing home visitation restrictions based on local conditions (Government Offices, 2020k).

2.3 Responses during the third wave

2.3.1 General population and community

After declining in January 2021, the infection rate again began to increase in February 2021, marking the beginning of the third wave. In light of this, several of the national restrictions and recommendations previously issued were extended and in some cases modified during February–April 2021. In the beginning of March 2021, restaurants and bars were, for example, required to end table service at 8:30 pm. They were furthermore restricted to only serving single patrons if the entrance is through a common area (e.g. a shopping mall) (PHA, 2021a). The maximum capacity of shopping centers, pools, gyms and sports facilities was also limited to 500 people, and commercial business were also directed to take actions to ensure that patrons shop alone (e.g. through signage) (PHA, 2021b). Apart from this, new restrictions on travelers to Sweden were also introduced in February 2021, requiring a negative COVID-19 test for EU/EES citizens entering the country (Government Offices, 2021c). The recommendations regarding remote learning in upper secondary schools were on the other hand not extended, and ended on 1st April 2021 (PHA, 2021c). In parallel with the national restrictions and recommendations, the individual regions also continued to issue adapted local recommendations during the period based on the spread of infection and the burden on health care in their own regions.

2.3.2 The elderly

Given increasing vaccine coverage among the elderly population and among health- and elder care staff, the PHA recommended an easing of restrictions on nursing homes in April 2021. Proposals include the resumption of common social activities and allowing visits outside of nursing homes (e.g. to family members and shops). It was noted, however, that this should be implemented successively at the local level based on local conditions (PHA, 2021d).

Taken together, previously mandated restrictions and recommendations were to a large extent maintained or in some cases strengthened during February–April 2021. Given the increasing prevalence of vaccination and reduced disease spread, a plan to successively roll back restrictions was adopted by the Government and PHA at the end of May 2021. The plan consists of five steps, the first of which was implemented on 1st June. This step entailed, for instance, that larger gatherings at cultural and sports events were permitted, as well as allowing later table service at bars and restaurants. Additional steps will ease these restrictions further, with the final step entailing the removal of all COVID-19-related restrictions. At the time of publication, a timetable for the final steps has not been set (Government Offices, 2021d).

3. Responses in health- and elder care

The regions and municipalities as providers of health and social care took numerous and diverse actions to address the challenges posed by COVID-19. These challenges included the need to ensure the capacity of the health care system and, in particular, Intensive Care Units (ICUs) to handle an influx of patients, scaling up testing capacity to meet strategic goals and ensuring that the vulnerable elderly population was protected. COVID-19 has highlighted a number of problems in the Swedish health- and elder care system.

3.1 Ensuring health care capacity

At the beginning of the pandemic, there were substantial concerns regarding the capacity of the health care system to handle the expected increase in patients requiring isolation precautions and ICU care. Thus, the NBHW was assigned the task of securing access to personal protective equipment (PPE) and other health care materiel on 17th March 2020 (Government Offices, 2020b), and coordinating an increase in ICU capacity on 20th March 2020 (Government Offices, 2020e). The bulk of activity to increase the capacity of the health care system in preparation for the pandemic has however occurred at the regional level, with some assistance from the military and other national actors. Collaboration between regions has increased, particularly with regard to ICU capacity and medication supply (SKR, 2020a). Collaboration has been reported to be more efficient, and issues that were previously difficult to solve, such as arranging home visits by mobile teams and care planning for elderly, are reported to be handled more pragmatically (SKR, 2020b).

Numerous measures have been taken during the pandemic to increase intensive and intermediate care unit capacity in Sweden. The primary bottleneck has been staffing, and additional staff for these units have been obtained through transfers from other specialties, the recall of recent retirees and nurses working in non-clinical roles, the hiring of hourly staff and by mandating additional working hours. These efforts resulted in a doubling of capacity from 500 to a peak of 1100 respirator-equipped beds, primarily through the conversion of specialist wards into ICU wards. There are concerns, however, that this reconfiguration may have squeezed out other forms of care particularly during the first wave (SKR, 2020a), and has increased pressure on staff due to longer work hours and canceled holidays.

A particular problem at the beginning of the pandemic was a lack of stockpiles of medical equipment, with many regions employing just-in-time provisioning, entailing that stockpiles at the regional level were small, and leading to material shortages even before the pandemic (SVT, 2019; Vårdfokus, 2020). There was thus initially a lack of PPE in many regions and municipalities, and no clear national guidelines for when and how to employ PPE. The lack of clear recommendations has resulted in confusion and harsh critique from some municipalities, unions and staff (DN, 2020a; SVT, 2020a). In practice, health care staff and most nursing home staff are obliged to use plastic visors and face masks. It seems, however, that problems with protective equipment procurement have diminished over time, and concerns over PPE provisioning have not been prominent during the third wave.

3.2 Increasing testing capacity

On 30th March 2020, the PHA was assigned the task of developing a national testing strategy by the government of Sweden. After community transmission of COVID-19 was identified, the PHA reasoned that there was little benefit to testing individuals with mild cases, and that given a lack of analytical capacity these cases could be deprioritized. A prioritization scheme was thus developed to direct testing toward those with a medical need (primarily patients treated at hospitals), followed by health care staff, and other workers with critical societal functions (PHA, 2020b). The PHA aided regions in building testing capacity by providing technical assistance, reserve supplies of reagents and coordination of alternative testing pathways (PHA, 2020i). Despite increasing test capacity however, the number of tests performed by the regions increased relatively slowly during the initial phases of the pandemic. Contributing factors may have included a lack of the materials necessary to conduct testing, limited analytical capacity in regional laboratories, as well as lack of staff.

Following the peak of the pandemics’ first wave in April 2020, the government sought to further increase the scale of COVID-19 testing, with the goal of ensuring that all individuals with symptoms regardless of priority group could be tested. Thus, on 5th June 2020, the PHA and the regions were directed to coordinate efforts to increase testing rates (Government Offices, 2020i). It was simultaneously announced that regions would be compensated by the national government for all COVID-19-related testing activities, including both polymerase chain reaction and antibody tests.

As shown in Figure 1, the rate of testing following these actions substantially increased. However, the public demand for testing nonetheless still outstripped testing capacity at times, leading to reports of ‘testing chaos’ in the media, and renewed efforts to increase testing capacity (DN, 2020c). State support for testing has continued throughout the second and third waves, with an additional 5.5 billion SEK allocated for testing in January 2021. As of the time of publication (July 2021), testing capacity appears to be sufficient to meet public demand with the rate of testing having steadily increased over the course of the pandemic. The process of contact tracing has also gained momentum with the help of the additional national funding allocated to the effort.

3.3 Ensuring quality and safety in elder care

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted nursing home residents particularly hard, with 42.5% of all mortalities occurring among nursing home residents as of May 2021 per NBHW statistics. The high mortality rates within those homes, administered by the municipalities, have been considered one of the most serious problems during the pandemic. Although substantial efforts have taken place in all municipalities to prevent the spread of the infection, the quality of care at nursing homes has been found to be highly varied, and in many cases, poor (IVO, 2020a). In the Stockholm area for instance, residents needing care were found to have not been appropriately evaluated by doctors or referred to hospitals (IVO, 2020b). This has raised questions regarding the provision of more advanced care in nursing homes, particularly when advanced home care is already available for other patient groups (SvD, 2020). In December 2020, the National Corona Commission presented its first report (SOU 2020:80) which included harsh criticism of the elder care sector, noting that the elderly care sector was unprepared and ill-equipped to deal with a pandemic despite quality deficiencies having been known for a long time in Swedish elder care. It was clearly stated that the government bears the ultimate responsibility for the shortcomings. Both responsible authorities – PHA and the NBHW – also received strong criticism for not responding to the crisis in time. More precisely, the committee identified structural shortcomings in elder care, and that care providers were poorly equipped for a pandemic. This was due to factors including insufficient regulations, unclear division of responsibilities between the government and the municipalities, as well as lack of staff and medical competence. Overall, the pandemic has clearly illustrated that the Swedish elder care system had underlying quality problems which were further exacerbated by the crisis.

3.4 Vaccination

Responsibility for vaccinations is divided between the state and regions which was formalized by agreement on 8th December 2020. As with testing, regions are responsible for the administration of vaccines upon delivery from the state (Government Offices, 2020n).

The vaccination campaign was divided into four phases. The first phase covered those with elder care services or living in care homes. Phase two included those older than 65 living at home, people with special care needs and health care personnel. Phase three covered those aged 60–64, and finally phase four covers those aged 18–59, with recent decisions by the PHA reducing the minimum age to 16 (PHA, 2021f). The overarching goal of the strategy was that every citizen was to be offered the first vaccination dose during the first half of 2021, but due to shortfalls in vaccine deliveries and decisions to pause some of the vaccines (e.g. AstraZeneca), the target date has been revised and is now the 19th of September (Government Offices, 2021e). As of 14th July 2021, 70% of the population have had one dose of any vaccine, and 45% have a full course of two doses (PHA, 2021e). At the time of publication, the vaccination campaign has been quite successful, although socioeconomically weaker groups have had a slower vaccination rate.

4. Discussion

The Swedish response to COVID-19 has been characterized by a reliance on voluntary measures, strategic decision-making by expert agencies, and a decentralized/collaborative health care response. The reliance on ‘softer’, non-binding restrictions can at least partially be explained by a long Swedish tradition of individual responsibility in combination with high trust in authorities (Ludvigsson, Reference Ludvigsson2020; Kuhlmann et al., Reference Kuhlmann, Hellström, Ramberg and Reiter2021). Another, more pragmatic explanation for the measured Swedish response is that authorities believed that compliance with the restrictions would be more sustainable were they less strict. Furthermore, the PHA has had a clear focus on avoiding negative long-term effects with regard to population health and wellbeing (e.g. declining school results and domestic violence) (Pierre, Reference Pierre2020). A final explanation may be found in the lack of legal authority to implement legally binding restrictions on individual freedom of movement.

Although the original policy response has not been abandoned, certain shifts in the response during the second and third waves may be discerned. First, a focus was placed during the second wave on containing local outbreaks of COVID-19 through increased testing and tracing, and local measures to further promote social distancing. Second, as the spread of the infection started to increase throughout the country, mandatory restrictions were directed at businesses and other organizations over which the government did have a legal basis for interventions, such as the restrictions on serving alcohol and on the number of people allowed at public gatherings. Over time, the Swedish response has thus come to include stricter measures, even though it still contains a mixture of both legally binding business regulations and voluntary (although strongly worded) recommendations directed at individuals. These changes bring the Swedish response more in line with how other countries responded to the pandemic, although it has never included a hard lockdown.

Furthermore, although the PHA has retained a leading role in coordinating the response throughout the pandemic, the government started to take a more prominent role in issuing restrictions and communicating the response at the national level already during the second wave. The legal framework has also been modified over the course of the pandemic, with the temporary pandemic law enabling a more regimented set of restrictions directed at the public and businesses during the second and third waves of the response.

Given the publication of this study during the denouement of the third wave, it remains difficult to determine the final impact and thus the effectiveness of the measures taken so far. However, some issues regarding the interplay between the national response and institutional conditions described previously are ripe for consideration.

A first issue regards challenges of clearly communicating policy responses to the public. Over the course of the second and third waves, modifications to the response have included more mandatory measures, an easing of some of restrictions, and a multiplicity of local guidelines. This has complicated the communication of the response to the population and caused some confusion regarding what applies when and where. An additional challenge has been that communications from authorities might pertain to recommendations, guidelines or regulations, all of which have specific legal meanings which might not be clear to the public. Whether a measure is legally binding can in some cases be difficult to ascertain, which has created problems in interpretation.

A second issue is how to strike a balance between a potent central governance and a nuanced regional response adapted to local conditions in the decentralized Swedish health care system. The pandemic has reignited discussions about the lack of coordination and the government's role in the health care system. Questions have been raised as to whether the traditional governance model built on collaboration and trust is efficient also during crises were decision need to be taken more swiftly (Pierre, Reference Pierre2020). Although collaboration between the regions has arguably improved during the pandemic, the multilevel governance model undoubtedly complicated the handling of the pandemic, regarding for instance testing and contact tracing. Although testing capacity has increased significantly, criticism has been directed at both expert agencies and regions for the slow ramp-up of testing capacity, despite the clear goals and funds set aside by the national government. These issues will require close examination, but are likely to stem in part from the fact that individual testing systems had to be built up by each region, and by a lack of clarity in the communication between the national and regional levels regarding funding and priority groups during the spring of 2020. Furthermore, the lack of medical inventories and PPE in many regions and municipalities, particularly during the initial phase of the pandemic, illustrates the difficulty in balancing inventory efficiency with contingency planning. The national government's responsibility for these matters has eroded over the past few decades, particularly through the deregulation of the national pharmacies in 2008, and may need to be reexamined.

A connected issue is whether the decentralized system makes it too difficult to maintain and monitor the quality of the health-, and particularly elder care services. Despite efforts to improve conditions and routines at municipal nursing homes, basic problems with low levels of education and a high prevalence of hourly workers remain, all of which have been found to be determinants of COVID-19 spread. The high death toll has also highlighted problems in the collaboration between the municipal elder care and the regional health care systems, such as confusion about the interpretation of clinical guidelines and the communication gap between physicians employed by the regions, and the nursing homes their patients reside in. Issues relating to the decentralized nature of Swedish health care may prove to be the most intractable, as they are deeply rooted in the Swedish tradition of regional autonomy and collaborative leadership.

A final issue to consider in the aftermath of the pandemic is the degree of autonomy to grant expert authorities in relation to the government during a crisis. In the Swedish case, the PHA was ‘at the helm of the ship’, and their expert knowledge formed the basis for a large number of decisions. Although this division of labor is in line with the administrative tradition in Sweden, it may be democratically problematic when a crisis response becomes too far removed from political authority. Kuhlmann et al. (Reference Kuhlmann, Hellström, Ramberg and Reiter2021) emphasize the need to consult knowledge from other fields besides epidemiology and virology regarding ‘high-stakes emergency decisions’ such as the pandemic, although this was arguably accomplished given the PHA's broad focus on long-term impacts.

As Sweden starts to open up again, decision-makers must reflect on the lessons of the COVID-19 pandemic, not only with regard to the effectiveness of specific policy responses, but also on the fundamental structure of the health- and elder care system and its ability to facilitate a clear, rapid and effective response to crises.