Hospital room occupation by patients carrying Clostridium difficile or a multidrug-resistant organism (MDRO) impart increased risk of acquisition by subsequent patients and likely serves as a reservoir for nosocomial pathogens.Reference Shaughnessy, Micielli and DePestel 1 , Reference Karpanen, Casey and Lambert 2

“No touch” measures, such as hydrogen peroxide vapor or ultraviolet light for enhanced terminal room cleaning have been shown to improve disinfection and reduce healthcare-associated infections (HAIs); however, these strategies are time and labor intensive and can only be employed in unoccupied rooms.Reference Humphreys 3 Constitutively active antimicrobial surfaces and fabrics represent novel approaches to reducing patient-to-patient transmission because they continuously act to reduce the bacterial burden.Reference Humphreys 3

Copper has broad microbicidal activity including bacteria, fungi, and viruses, in addition to the vegetative and, with reduced potency, spore forms of C. difficile.Reference Karpanen, Casey and Lambert 2 , Reference Humphreys 3 Deployment of copper surfaces has been shown to reduce MDRO colonization of hospital surfaces.Reference Karpanen, Casey and Lambert 2 Limited clinical evidence also suggests that copper surfaces and/or linens may reduce HAIs among intensive care unit (ICU) patients (copper surfaces only),Reference Salgado, Sepkowitz and John 4 among non-ICU inpatients (surfaces and linens),Reference Sifri, Burke and Enfield 5 and at a long-term care facility (linens only).Reference Lazary, Weinberg and Vatine 6 We hypothesized that implementing copper linens in a long-term acute-care hospital (LTACH) would reduce incidence of healthcare facility-onset Clostridium difficile infection (HO-CDI) and MDRO acquisition.

Methods

Copper-impregnated woven linens including bed sheets, fitted sheets, pillowcases, towels, and washcloths (Cupron Medical Textiles; Cupron, Richmond, VA) were deployed on October 6, 2014, at a 40-bed LTACH in Charlottesville, Virginia. The linens were removed over the month of January 2017 after monitoring for HO-CDI and MDRO acquisition showed no benefit.

We retrospectively analyzed healthcare facility-onset CDI (HO-CDI) events according to the National Health and Safety Network (NHSN) laboratory-identified (LabID) definitions 7 and HO-MDRO acquisition. HO-MDRO acquisitions, defined as a new finding compared to known status, were detected by routine surveillance (perirectal or ostomy swab and MRSA nares swab on admission and weekly thereafter) or NHSN LabID HAIs. 7 Swabs were tested for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) using Xpert MRSA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA) and for vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) using Spectra chromogenic agar (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Lenexa, KS).Reference Ubukata, Nakagami and Nitta 8 , Reference Peterson, Doern and Kallstrom 9 Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) and extensive drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (≥3 antibiotic classes) were identified following selective incubation and subculture to Colorex agar (Northeast Laboratory Services, Winslow, ME), followed by modified carbapenem inactivation with Carba-R PCR (Cepheid) or susceptibilities, respectively.Reference Wayne 10 – Reference Magiorakos, Srinivasan and Carey 12 Facility hand hygiene compliance auditing data were also collected during a combination of 12-hour day and night shifts.

Monthly incidence rates were analyzed over a 27-month control period prior to implementation (July 2012 through September 2014) followed by a 27-month intervention period (October 2014 through December 2016), and an additional 10-month control period (January 2017 through October 2017).

Rates of hygiene compliance (ie, hand hygiene before and after patient care) were measured through an anonymous auditing program that did not change over the course of the study period. An average of 40 hand hygiene opportunities were assessed per month. Clostridium difficile infection testing was performed using real-time PCR of the tcdB gene (Cepheid) during the entire study. Universal contact precautions were employed throughout the study period with good (>92%) audited compliance that did not vary significantly over time.

Statistical P values were obtained using 2-tailed independent samples t tests for equality of means. In addition, interrupted time-series analyses were performed using quasi-Poisson regression, with patient days as an offset and hand hygiene compliance as a covariate.

Results

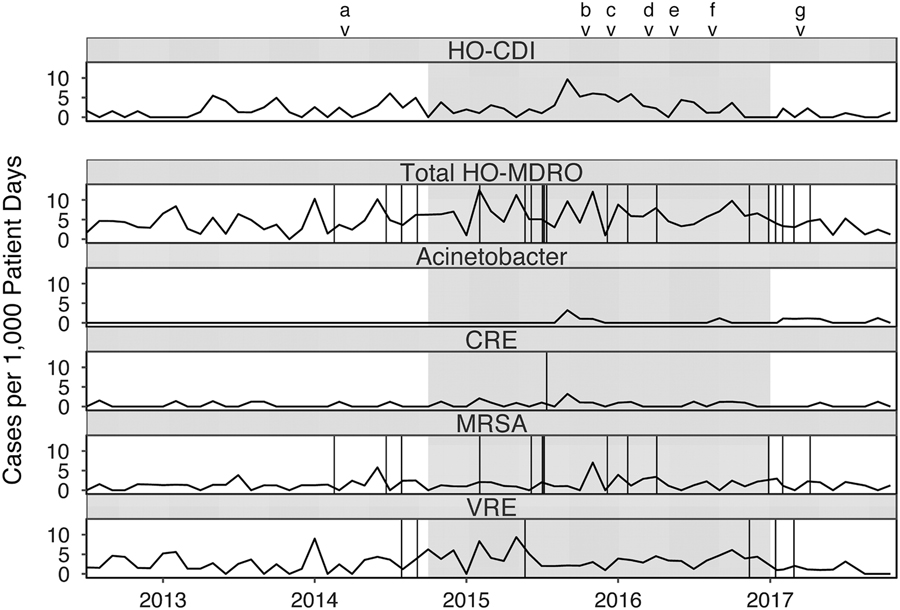

Overall, 29,342 patient days were observed during the control period and 25,243 patient days were observed during the intervention (Table 1). Copper linens were associated with significantly higher rates of HO-CDI (P=.023) and total HO-MDRO acquisition (P=.001). In subgroup analysis, differences in total HO-MDRO acquisition were largely attributable to VRE (2.1 acquisitions per 1,000 patient days during control vs 3.8 during the intervention; P=.002) and to CRE (0.3 acquisitions per 1,000 patient days during control vs 0.7 during the intervention; P=.044). Comparisons of the relatively small number of HO-MDRO infections during each period revealed no significant differences (P=.313). Rates of HO-CDI, HO-MDRO acquisitions, and changes in infection control–related practices over the study period are depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Rates of healthcare facility-onset Clostridium difficile infection (HO-CDI) and multidrug-resistant organism (HO-MDRO) acquisition events with copper linens intervention (grayed). Vertical lines represent NHSN-reported healthcare-associated infection events due to MDROs (CRE: urinary tract x1; MRSA: bloodstream x6, pneumonia x1, ear eyes nose throat x1, lower respiratory x2, skin and soft tissue x1, ventilator-associated event x2; VRE: bloodstream x1, gastrointestinal x1, urinary tract x4). Note. CRE, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae; MRSA, methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus; VRE, vancomycin-resistant enterococci. aBegan offering yogurt to patients. bHand hygiene competency evaluation for all staff. c10 new mattresses purchased. dLarger C. difficile signs placed in rooms. eInstituted twice weekly universal bleach disinfection of all rooms. fBeds replaced due to mechanical failure. gBed deck covers deployed.

Table 1 Effect of Copper Linens on Rates of HO-CDI and HO-MDRO Acquisition

Note. HO-CDI, healthcare facility-onset Clostridium difficile infection; HO-MDRO, healthcare facility-onset multidrug-resistant organism; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; HAIs, healthcare-associated infections; VRE, vancomycin-resistant enterococci; carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae.

a Incidence rates are per 1,000 patient days. Significant P values<.05 are shown in boldface type.

Poorer mean monthly hand hygiene compliance occurred during the intervention period (90.9% vs 95.3% for the control period). Quasi-Poisson models demonstrated a similar effect on total HO-MDRO acquisition (P=.001); however, HO-CDI was no longer significantly different among groups (P=.081). See the supplementary material for hand hygiene and modeling data.

Discussion

Contrary to our hypothesis, our data do not suggest a beneficial effect of bed/bath copper linens for reducing HO-CDI or HO-MDRO acquisition. Our findings contrast with a study of Israeli long-term care facility patients that demonstrated significant reductions in HAIs (24% reduction), fevers (47% reduction), and bacterial loads measured from sheets with copper linens.Reference Lazary, Weinberg and Vatine 6 Several major differences may explain our disparate findings, including the additional use of copper-impregnated personnel uniforms, high baseline HAI rates that could amplify copper effects, and differences in primary outcomes between the studies.Reference Lazary, Weinberg and Vatine 6

Although our data demonstrated increased HO-CDI and HO-MDRO acquisition during the intervention period, there are several reasons to question a causative role by copper, including the well-described reduced bioburden by copper materialsReference Karpanen, Casey and Lambert 2 , Reference Humphreys 3 and studies showing clinical benefit in other settings.Reference Salgado, Sepkowitz and John 4 – Reference Lazary, Weinberg and Vatine 6 The likelihood of the development of microbial resistance to copper is likely small due to the multiple mechanisms of copper’s microbicidal action. In the United Kingdom, bacterial resistance has not been observed, despite wide deployment of copper.Reference Karpanen, Casey and Lambert 2 However, staff and patients were not blinded to the intervention; thus, we cannot rule out that copper linens may have resulted in degradation of other infection control practices, including hand hygiene, possibly leading to increased pathogen transmission. Similar hypotheses have been advanced to explain the negative correlations between glove use and hand hygiene compliance.Reference Cusini, Nydegger, Kaspar, Schweiger, Kuhn and Marschall 13 Notably, no changes to the institutional antibiotic formulary or policies occurred during the study period.

This study has several limitations. While quasi-experimental studies are often pragmatic within the field of healthcare epidemiology, time-varying factors and overlapping interventions (Fig. 1) may have introduced bias by influencing surveillance detection of infection events or MDRO transmission. Also, the NHSN surveillance definition for CDI changed beginning in January 2016 from infection surveillance reporting to LabID event reporting, so that symptoms of CDI were no longer required to be present. 7 Therefore, CDI detection may have been inflated during the latter portions of the intervention and control periods. Linens were laundered using standard protocols (according to manufacturer recommendations) and although the manufacturer reports the linens degrade microbes for the life of the product, we cannot rule out the possibility that the antimicrobial properties may have waned over time.

Despite some limitations, our study has several notable aspects. First, the add-and-remove treatment design strengthens the evaluation of time-varying factors.Reference Harris, Lautenbach and Perencevich 14 Second, point-prevalence MDRO surveys were collected on admission and weekly to determine new colonization events. Most previous studies of copper-containing products only reported rates of clinical infections but not rates of new colonization events; predictably, this will underestimate the rate of new total acquisitions.

While we did not observe a beneficial effect, copper-impregnated surfaces with or without copper-impregnated linens may be useful in other settings as an adjunct strategy to existing infection control practices, particularly if incidences of HAIs and MDRO transmission are high and infection control practices do not degrade with their use. Trials with more rigorous study designs (eg, randomized clinical trials) and relevant endpoints (eg, new total acquisition rates) are needed to define the efficacy of copper linens and/or surfaces in healthcare settings.

Supplementary materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2018.196

Acknowledgments

We thank Tara Beuscher DNP, RN for her work implementing use of copper linens and for data collection. The authors alone were responsible for conducting the trial, collecting the data, interpreting the results, and writing the manuscript.

Financial support

Copper-containing textiles used in the study were lent free of charge by Cupron. This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health Infectious Diseases Training Grant (no. 5T-32AI007046-41).

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.