Similar to patients in the acute-care setting, patients receiving home infusion therapy may be at risk of central-line–associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI). The extent of this burden has not been characterized because no surveillance definition for home-infusion–associated CLABSI has been validated.

In the acute-care setting, national policies have resulted in widely accepted CLABSI surveillance definitionsReference Mermel and Alang1–4 that are reported through the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN).2,Reference Mermel, Allon and Bouza5,6 The implementation of CLABSI surveillance definitions, mandated reporting, and benchmarking has encouraged an emphasis on acute-care CLABSI prevention and had resulted in a 50% drop in the CLABSI standardized infection ratio (SIR) prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.Reference Pronovost, Marsteller and Goeschel7–10

For patients on home infusion therapy, no standardized CLABSI definition has been validated. A 2008 home-healthcare–associated bloodstream infection (BSI) definition developed by the Association for Professionals in Infection Control/Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee11 relied on NHSN acute-care CLABSI surveillance criteria in use at the time.2 Adoption has been limited in partReference Rinke, Bundy and Milstone12 because it lacks essential components contained in the current NHSN acute-care CLABSI definition,13 such as how to distinguish a BSI from a common commensal and denominator criteria.Reference Kramer14,Reference Keller, Williams, Rock, Deol, Trexler and Cosgrove15 Experts vary nationally in how they define home-infusion CLABSIs, particularly the optimal numerator, denominator, and inclusion and exclusion criteria.Reference Keller, Alexander and Williams16 Initiatives through the National Home Infusion Association (NHIA), the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN), and the home-health Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS) encourage reporting of home-infusion complications but do not specifically define CLABSI.17–20 In earlier work, we convened a team of experts to create a surveillance definition for CLABSI in home infusion therapy,Reference Keller, Salinas and Williams21 and we identified barriers and mitigating strategies to home-infusion CLABSI surveillance.Reference Oladapo-Shittu, Hannum and Salinas22,Reference Hannum, Oladapo-Shittu and Salinas23 The resulting definition required validation prior to wider use.

Gathering sufficient data to determine whether a BSI meets criteria for a secondary BSI may be particularly difficult in home infusion therapy because it requires access to information from unaffiliated hospitals.Reference Hannum, Oladapo-Shittu and Salinas23 Hospital-onset bacteremia and fungemia (HOB)—any BSI ≥48 hours after hospital admission—may better distinguish hospital-level performance,Reference Rock, Thom and Harris24,Reference Dantes, Rock and Milstone25 and hospitals may soon report HOB.26 Earlier work did not characterize optimal approaches to secondary BSI in home-infusion CLABSI surveillance.Reference Keller, Salinas and Williams21

The objective of this work was (1) to demonstrate the validity of a home-infusion CLABSI definitionReference Keller, Salinas and Williams21 and (2) to determine surveillance staff perceptions of the feasibility and acceptability of the definition. Based on concerns about the potential difficulty of applying secondary BSI definitions in home infusion therapy, we also examined the impacts of 3 different approaches to handling secondary BSIs on definition validity.

Methods

Overall research approach

We performed a mixed-methods study including quantitative validation of the application of the CLABSI definition and qualitative semistructured interviews with home-infusion CLABSI surveillance staff focused on experiences with definition implementation. The study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board.

Setting

The Home Infusion CLABSI Prevention Collaborative (HICPC) is a collaborative of 5 large home-infusion agencies affiliated with academic medical centers. The agencies include 2 in the mid-Atlantic, 1 in the northeast, and 2 in the Midwest, and it covers portions of 14 states and Washington, DC. Also, 5 agencies implemented the definition, but due to institutional review board constraints, only 4 agencies submitted data for validation.

Definition development and implementation

We used an expert-informed definition adapted from the acute-care NHSN CLABSI definition.Reference Keller, Salinas and Williams21,27 Staff performing CLABSI surveillance at each agency participated in interactive monthly webinars focused on CLABSI surveillance and prevention and interacted with experts via videoconferences and emails. Staff attending the webinars were encouraged to present cases for discussion. In addition, we provided checklists and instructions for CLABSI surveillance.

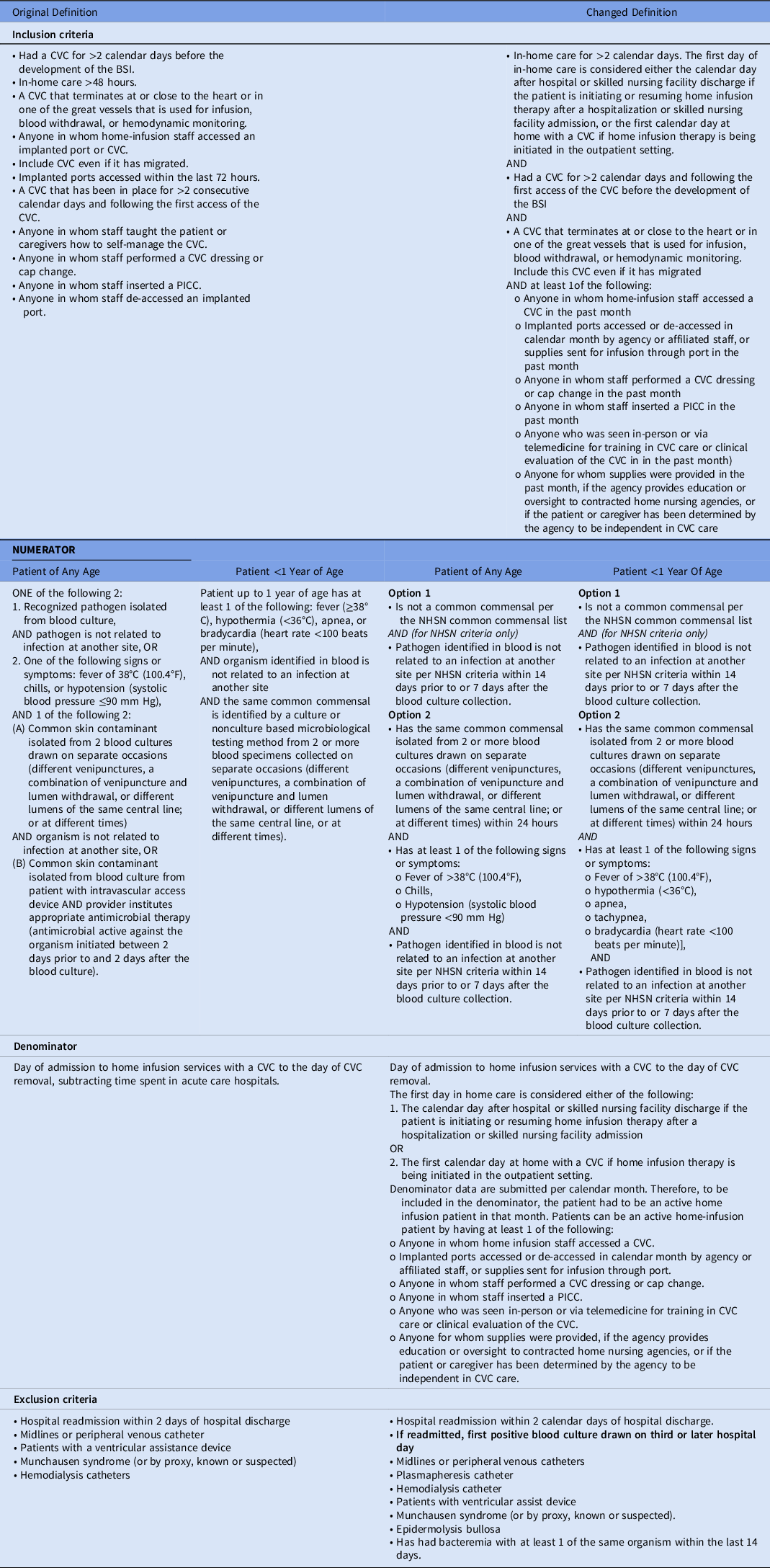

Collaborative members began applying the CLABSI definition in May 2021. Based on feedback, we made minor modifications to the definition through July 2021. We applied changes retroactively (Table 1).Reference Keller, Salinas and Williams21 We asked HICPC members to apply 3 different variations of the definition based on approaches to secondary BSIs: (1) secondary BSIs were excluded if they met NHSN criteria, referred to as “NHSN criteria”; (2) a subset of common secondary BSIs meeting NHSN criteria were excluded (ie, pneumonia or PNU2 or PNU3; urinary tract infection or SUTI1a, SUTI1b, or SUTI2; gastrointestinal infection or GIT2a, GIT2b, GIT2c, or GIT3b; and intraabdominal infection or IAB1, IAB2b, IAB3a, or IAB3b),27 referred to as “modified NHSN criteria”; or (3) no secondary BSIs were excluded, referred to as “home-infusion–onset bacteremia (HiOB) criteria.”

Table 1. Original and Final Definition for CLABSI in Home Infusion Therapy

Note. CVC, central venous catheter; PICC, peripherally inserted central catheter; NHSN, National Healthcare Safety Network.

Validation of CLABSI surveillance

Because the central study team did not have access to the electronic health record (EHR) systems of all agencies or admitting hospitals, each agency was asked to upload all data they would use to make a CLABSI determination for each patient with positive blood cultures. Such information included emergency department notes, history and physical, signs and symptoms, progress notes, procedure notes, discharge summaries, pathology reports, radiology reports, and microbiology reports. In addition, each agency was asked whether the case met either of the 3 CLABSI definition variations, and if so, to describe which of the 3 criteria they met or provide information about secondary BSI criteria. Additional data were requested on patient demographics, central-line information, and other clinical data. Denominator data were also requested. Data were requested on a monthly basis from May 2021 through June 2022. An experienced IP (K.W.) blinded to the agency’s CLABSI determination reviewed all submitted data and determined whether the case would meet any or all of the CLABSI criteria. All positive blood cultures were presented for review.

Analysis of CLABSI data

We first calculated CLABSI rates per 1,000 home-infusion central-line (CL) days. Data were calculated per agency overall, per agency over time, over all agencies, over all agencies over time, for the 3 definition variations, and as ascertained by both the agency and the IP validator. Descriptive statistics described the CLABSI rates for each agency.

We calculated interrater reliability (IRR) using the κ (kappa) statistic, comparing CLABSIs as ascertained by each agency and as ascertained by the IP validator. IRR was calculated for each of the 3 definitions, and separately for each agency. Because of concern that data might be asymmetric, we also calculated percentile agreement.Reference McHugh28 Sensitivity and specificity were calculated using all submitted cases with bacteremia and the validator CLABSI determination.Reference Oh, Cunningham and Beldavs29

Qualitative interview procedures

We constructed a semistructured interview guide focused on the home-infusion CLABSI surveillance definition’s feasibility, adoption, maintenance, acceptability, appropriateness, costs, and implementation strategies.Reference Proctor, Silmere and Raghavan30 We used purposive sampling to recruit semistructured interview participants.Reference Miles, Huberman and Saldana31 We started by purposively asking 1–4 staff members for each of the 5 agencies engaged in CLABSI surveillance to participate. We attempted to interview each eligible staff member twice after the May 2021 definition implementation: 1 month after using the definition and again 3–4 months after using the definition. After obtaining written consent, all interviews were conducted remotely via videoconferencing and lasted between 20 and 60 minutes. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. We modified the definition based on findings from the first set of interviews and discussions in webinars.

Qualitative data analysis

At the end of each interview, we sent audio files of recorded interviews to a licensed transcriptionist. Transcripts were deidentified and uploaded into MAXQDA for qualitative data management and analyses (VERBI Software, Berlin, GA). The initial codebook was developed deductively from the interview guide. The interview guide examined feasibility, adoption, maintenance, acceptability, appropriateness, costs,Reference Proctor, Silmere and Raghavan30 and implementation strategies. Deductive codes were applied to the first 3 interview transcripts. In addition, we inductively identified emergent subcodes to each parent code. This initial coding process was conducted by S.H. and S.C.K. Disagreements in coding were rectified to coder agreement.Reference Saldana32 S.H. then coded the remainder of the data. S.H. and S.C.K. discussed emergent findings and modifications to the coding framework (Supplementary Material online). We engaged in a process of constant comparison of emergent findings throughout the analysis and when no new codes could be identified, we considered thematic saturation to have been achieved.Reference Ando, Cousins and Young33

Results

Validation

Agencies reported information on all patients with positive blood cultures, including 93 positive blood cultures for agency 1; 51 patients with positive blood cultures for agency 2; 60 patients with positive blood cultures for agency 3; and 40 patients with positive blood cultures for agency 4.

IRR, percent agreement, and sensitivity and specificity are liste in Table 2. IRR overall ranged from κ = 0.66 and 86.6% agreement for the modified NHSN criteria, to κ = 0.68 and 86.2% agreement for the NHSN criteria, to κ = 0.72 and 91.5% agreement for the HiOB criteria (Table 2). IRR varied between agencies, as did the definition variant for which agencies had the highest IRR. For agency 1, the HiOB variation was the most reliable; for agency 2, the modified NHSN variation was the most reliable; and for agency 3, the HiOB variation was the most reliable. Some reasons for discrepancies in CLABSI or HiOB classification included erroneous application of mucosal barrier injury criteria (due to anticipated difficulties in accessing data on neutropenia or diarrhea volume, mucosal barrier injury criteria was not included in the definition)Reference Keller, Salinas and Williams21 and becoming accustomed to applying the definition.

Table 2. Interrater reliability, Sensitivity, Specificity, and Percent Agreement of Surveillance Staff of Home Infusion Agencies when Compared with Validator, for Each of Three Approaches to Handling Secondary Bloodstream Infections

Note. CI, confidence interval; NHSN, National Health Safety Network.

We also calculated CLABSI rates per 1,000 CL days (Table 3). For the NHSN criteria, the validator-determined rate was 0.20 per 1,000 CL days. For the modified NHSN criteria, the validator-determined rate was 0.21 per 1,000 CL days. For the HiOB criteria overall, the validator-determined rate was 0.23 per 1,000 CL days. Agency monthly CLABSI rates are reported for each variation definition (Fig. 1).

Table 3. CLABSIs per 1,000 Central-Line Days and Total CLABSIs per Home Infusion Agency Surveillance Staff and Per the Validator, for Each of the Three Approaches to Secondary Bloodstream Infections

Note. CLABSI, central-line–associated bloodstream infection; CL, central line; NHSN, National Health Safety Network.

Fig. 1. Central-line–associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI) rates per month per 1,000 central venous catheter days based on rates as determined by the single central-study team validator. Rates are reported across all agencies based on the full National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) criteria, modified NHSN criteria, and home infusion onset bacteremia (HiOB) criteria.

Qualitative interviews

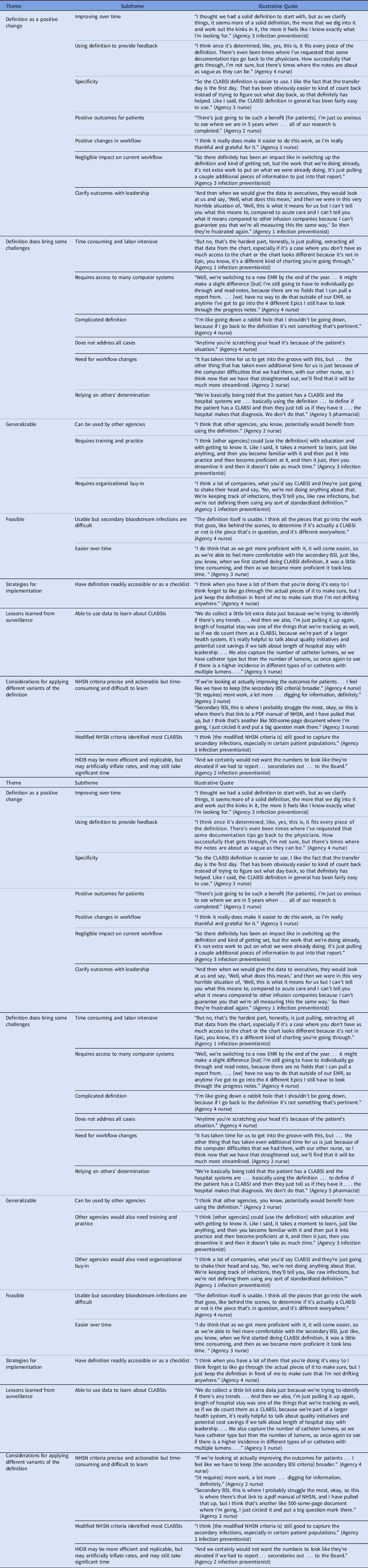

We interviewed HICPC members from the 5 agencies: 6 participants were interviewed 1 month after definition implementation and 8 participants were interviewed 3 months after implementation (Table 4). We identified 7 themes: (1) seeing the definition as a positive change, (2) identifying that the definition brought challenges, (3) seeing the definition as generalizable, (4) seeing the definition as feasible, (5) strategies for implementation, (6) lessons learned, and (7) considerations for applying different variants of the definition (Table 5).

Table 4. Characteristics of Home Infusion Agency Staff Participating in Semistructured Interviews 1 Month and 3–4 Months After Implementation of the Home Infusion CLABSI Surveillance Definition

Note. CLABSI, central-line–associated bloodstream infection.

Table 5. Perceptions of the Definition and Its Implementation

Note. BSI, bloodstream infection; CLABSI, central-line–associated bloodstream infection; EMR, electronic medical record; HiOB, home-infusion–onset bacteremia; NHSN, National Health Safety Network.

Overall, participants saw the definition as a positive change. They observed that the definition improved over time and provided useful data for feedback. They noted that the definition was specific. They felt that it led to positive outcomes for patients, with negligible negative impact on workflow. It also helped them clarify outcomes with leadership. Participants did note that the definition brought challenges, including being time-consuming and labor intensive, requiring access to many EHRs, being complicated, not covering all patient situations, and relying on others’ determination.

Participants noted that the definition was generalizable. They felt that the definition could be used by other agencies, although it required training and practice as well as organizational buy-in. They also felt that the definition was feasible. They thought that the definition was usable, although understanding secondary BSIs was difficult. Strategies for implementation were suggested, particularly having the definition readily accessible or using a checklist when performing surveillance. Respondents also noted that they had learned lessons from CLABSI surveillance and could use data to learn about CLABSIs.

Respondents discussed consideration for applying the 3 definition variants. Overall, participants across agencies had positive perceptions of the NHSN criteria which they felt were precise and actionable but also felt that using secondary BSI criteria was time-consuming and difficult to learn. Meanwhile, respondents felt that the modified NHSN criteria identified most CLABSIs and was less time- and effort-intensive than the NHSN criteria. Finally, although some participants felt that the HiOB criteria were more efficient and replicable, they also felt that the HiOB criteria could inflate CLABSI rates. Others felt that using the HiOB definition would not save them as much time because they would still need to access and review similar amounts of data.

Discussion

We worked with 5 large home-infusion agencies spanning parts of 14 states and the District of Columbia to refine, validate, and implement a surveillance definition for CLABSI in home infusion therapy. Overall, the reviewers showed good agreement with the trained IP using all 3 definition variations,Reference McHugh28,Reference Altman34 although there were differences in how closely the agency staff and an IP agreed on the definition. The agency members saw the definition as a positive change, although it required time and training. Our research shows that the CLABSI definition was valid and that its implementation was feasible. The CLABSI rate of 0.21–0.23 per 1,000 CL days is lower than in acute-care settings, where the rate was 0.9 per 1,000 CL days in 2018.Reference Sapiano, Dudeck and Soe35

Application of the definition reached a “good” level of interrater reliability. The sensitivity and specificity shown here compared favorably with validations of inpatient data. Definitions of acute-care CLABSIs have shown sensitivities of 42%–88% and specificities of 70%–99%.Reference Larsen, Gavin, Marsh, Rickard, Runnegar and Webster36 Meanwhile, state health departments validating CLABSI reporting to the NHSN have reported a sensitivity of 83% and specificity of 99%.Reference Bagchi, Watkins, Pollock, Edwards and Allen-Bridson37 Sensitivity in our study ranged from 88% to 93%, while specificity in our study ranged from 79% to 83%. Overall, the validity of agency staff applying the home-infusion CLABSI definition was similar to these reports from acute care.

Participants felt that the NHSN criteria was more time-consuming and difficult to perform than the HiOB criteria, and we learned in initial webinars and early interviews with CLABSI surveillance staffReference Hannum, Cosgrove and Gurses38 that access to EHR-based data needed for application of NHSN secondary BSI criteria was incomplete and varied by site. There were no substantial differences between the CLABSI rates based on the 3 definition variations, which ranged from 0.20 to 0.23 per 1,000 CL days. Use of the HiOB criteria did not substantially inflate the CLABSI rate. IRRs ranged from 0.65 for the modified NHSN criteria, to 0.68 for the NHSN criteria, to 0.72 for the HiOB criteria. In acute care, hospitals may begin reporting HOB, similar to HiOB, as early as 2023.26 Data showed that although HOB data may be easily extracted from the EHR and HOB rates closely paralleled those of hospital CLABSIs,Reference Rock, Thom and Harris24 only 54% of hospital epidemiologists viewed HOB as reflecting quality. Many hospital epidemiologists preferred reporting both CLABSIs and HOB.Reference Dantes, Abbo and Anderson39 HICPC members reviewing these data felt that the NHSN criteria made their CLABSI reporting more actionable and was important for agency quality and safety initiatives. Therefore, they requested that they continue to report both the NHSN criteria and HiOB criteria.

We examined perceptions of the definition. Overall, participants viewed the definition as a positive change with some challenges. They felt that it was generalizable and feasible. They provided strategies for implementation such as having a definition readily accessible or as a checklist (similar to that available for acute-care settings40 ). Finally, they provided considerations for applying different variants of the definition.

Agencies had prior experience in CLABSI surveillance, but earlier work noted barriers to home-infusion CLABSI surveillance. Barriers included having complicated tasks, the need for education in surveillance tailored to this setting, the need for assistance from information technologists and data analysts, the requirement for organizational support, and the need to manage information and communication.Reference Oladapo-Shittu, Hannum and Salinas22,Reference Hannum, Oladapo-Shittu and Salinas23 Therefore, we supported and guided agencies through approaches such as providing educational resources, suggestions on how to work with information technology, and interactive webinars. Providing education, enabling communication, and ensuring EHR support are essential.

Our research had several limitations. The agencies involved in the study were interested in CLABSI surveillance and may not represent agencies nationally. Due to ownership struggles, 1 participating home-infusion agency could not fully undergo approval from their institutional review board. Therefore, although 5 agencies participated in the qualitative interviews and the implementation of the definition, only 4 agencies participated in the validation of the definition. Due to ownership changes, changes in EHR vendors, difficulties accessing appropriate data, and staffing constraints related to the COVID-19 pandemic, some agencies had more challenges with data submission than others, although all were asked to initiate the definition at the same time.

We also depended on 1 trained IP to serve as the validator, but cases were frequently discussed with multiple members of the team. We depended on agencies to submit chart data to the central study team for use in validation. The central study team did not have access to the full EHR of all hospitals to which patients could be admitted (even individual home infusion agencies did not always have access to the EHRs of all hospitals to which patients could be admitted).Reference Hannum, Oladapo-Shittu and Salinas23 Therefore, we were unable to ascertain whether agencies had truly submitted all relevant data. However, in this real-world study, the agencies provided us with access to the same data they could access. Agencies may not have known whether there were relevant data (eg, an unavailable progress note) that could help in making their determination. Future work should examine approaches to address data that were missing but not at randomReference Malinsky, Shpitser and Tchetgen Tchetgen41 and the future impact of changing access to data.

The surveillance staff at each agency required extensive training and support in application of the definition, which may limit generalizability. We recently described the need for ongoing education in those performing home-infusion surveillance,Reference Oladapo-Shittu, Hannum and Salinas22 such as through modification of pre-existing resources through the CDC and national organizations, development of new resources, or peer-learning collaboratives, and in training in accessing data. Finally, in home infusion therapy, patients with BSIs are typically cared for in hospitals and not in the home, so the agencies themselves were infrequently involved in blood-culture decisions. Hospitals to which home-infusion patients may be admitted may differ in their blood-culture practices.

We performed the first validation study of a home-infusion CLABSI surveillance definition and found that the definition was valid, feasible, and acceptable. CLABSIs in this setting occur at a lower rate than in acute-care hospitals. In addition, differences between using an NHSN approach to secondary BSIs and an HiOB approach had minimal impact on infection rates or validity, suggesting that each of these approaches may be acceptable and that agencies may choose which approach works best for their setting. System-level supports, such as training in surveillance and better integration of EHRs, would be helpful. Additional research should investigate acceptability of the definitions among other stakeholders (eg, leadership or frontline staff) as well as larger-scale validation of the definitions and use this definition to test CLABSI prevention interventions. National implementation of the home-infusion CLABSI definition would provide critical surveillance data to motivate and inform efforts to prevent CLABSIs in home infusion therapy.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2023.70

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of the following CDC consultants for their advice and support in this work: Denise Leaptrot, MSA, SM/BSMT(ASCP), CIC, and Dominique Godfrey-Johnson, MPH, CPH, CIC.

Financial support

This work was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (grant no. R01HS027819 to S.C.K.). The funding agency had no role in the performance of this work.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.