Antibiotic overuse is common, costly, and harmful. 1,2 In 2019, nearly 5 million people died worldwide from the consequences of antimicrobial resistance. Reference Murray, Ikuta and Sharara3 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that 2.8 million antimicrobial-resistant infections occur in the United States annually resulting in at least 35,000 deaths. 2 In addition to antibiotic resistance, antibiotics commonly cause side effects: one retrospective study found that up to 20% of hospitalized patients treated with antibiotics suffered an antibiotic-related side effect. Reference Tamma, Avdic, Li, Dzintars and Cosgrove4

To address the growing health crisis caused by antibiotic resistance, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and other accrediting bodies have mandated that hospitals have antibiotic stewardship programs (ASPs) to promote optimal antibiotic use. 5 In the past decade, such programs have become nearly ubiquitous across US hospitals. 6 ASPs are ideally co-led by infectious disease–trained physicians and pharmacists and, to date, have focused mainly on antibiotic prescribing as the primary behavior in need of change. More recently, increasing attention has been given to upstream causes of antibiotic overuse and misuse, including inaccurate, unclear, and overused diagnostic testing. Reference Morgan, Malani and Diekema7–Reference Sullivan10 Thus, many have turned to diagnostic stewardship strategies to improve antibiotic prescribing, especially strategies that focus on optimizing the use and interpretation of infectious diseases–related diagnostic tests.

This publication is part of a series whose purpose is to provide an overview of diagnostic stewardship. Here, we discuss the distinct and complementary relationship between diagnostic and antimicrobial stewardship and demonstrate how diagnostic stewardship interventions may complement ASPs.

Why is diagnostic stewardship critical for antimicrobial stewardship?

Although ASPs often focus directly on antimicrobial use, diagnostic testing is a key driver of antimicrobial prescribing. Clinicians often use diagnostic test results to refine differential diagnoses and determine clinical management, including antimicrobial use. Diagnostic test utilization is a complex process that begins, in theory, with the clinician’s decision to order a test and ends with actions based on the interpretation of test results. Accurate test use requires the clinician to assess the clinical value of the test being considered for a particular patient (ie, what is the pre-test probability of the disease of interest, what the test measures, what information the results provide, and what is the clinical impact and cost implications of testing for this indication or scenario). Unfortunately, clinical diagnoses do not often proceed linearly or logically. Commonly, diagnosis and treatment occur in tandem, and test ordering and interpretation may be performed by different clinicians or teams. Moreover, clinicians often do not consider test and patient characteristics when ordering or interpreting tests, thus leading to reflexive ordering of unnecessary, low-value tests, and reflexive antibiotic treatment when those tests return positive. Consequently, diagnostic test overuse frequently results in antibiotic overuse and misuse.

Although infectious diseases are often clinical diagnoses, many infectious syndromes increasingly rely on or incorporate diagnostic testing. Unfortunately, no diagnostic test is 100% accurate. For example, not all “positive” tests represent infection; some represent false positives and others represent colonization rather than active infection. As the number of diagnostic tests grows in infectious diseases with the advent and widespread adoption of highly sensitive rapid molecular technologies, the existing problem of diagnostic test overuse and misuse is growing rapidly. Furthermore, once antibiotic treatment is started and a working diagnosis is made, diagnoses persist even when inconsistent or contradictory information comes to light. This “diagnostic momentum” leads to antibiotic momentum. Reference Gupta, Petty and Gandhi11 Thus, diagnostic stewardship strategies are critical to improving test utilization, reducing diagnostic anchoring, and preventing downstream antibiotic overuse.

Differences between antimicrobial stewardship and diagnostic stewardship interventions

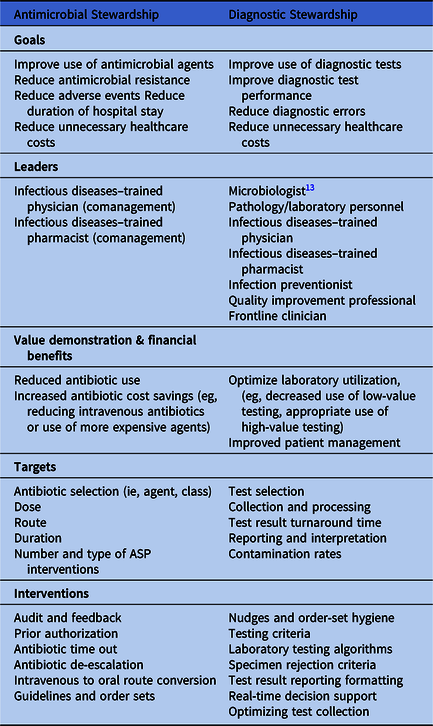

Both antimicrobial stewardship and diagnostic stewardship seek to improve patient outcomes. They have, however, notable differences (Table 1). Diagnostic stewardship focuses on the process of diagnostic testing, that is, use, performance, reporting, and interpretation. Commonly used metrics include diagnostic accuracy and/or test characteristics (ie, sensitivity and specificity) and laboratory utilization (ie, cost and efficiency). Antimicrobial stewardship focuses mainly on antimicrobial prescribing and appropriate use, that is, selection, dose, route, and duration. Commonly used metrics include antibiotic use (eg, days of therapy), antibiotic appropriateness, antibiotic-related harm (eg, Clostridioides difficile infections), and antibiotic resistance. Because these targets and outcomes differ, diagnostic stewardship and antimicrobial stewardship often have different approaches to changing clinician behavior. Fundamental antimicrobial stewardship interventions involve human-to-human interventions, often performed by ASP team members with antimicrobial expertise. Such interventions involve education, persuasion, handshake stewardship, Reference Hurst, Child, Pearce, Palmer, Todd and Parker12 and prospective audit and feedback. Antimicrobial stewardship relies heavily on infectious disease–trained pharmacists or physicians who often provide real-time guidance on antimicrobial use to influence clinician prescribing practices. Therefore, the success of many antimicrobial stewardship interventions relies on the effective collaboration between the ASP and the clinical teams they seek to influence.

Table 1. A Comparison of Antimicrobial Stewardship and Diagnostic Stewardship

In contrast, diagnostic stewardship strategies commonly involve technical solutions to improve diagnostic test use and interpretation. These interventions often occur earlier in the clinical work-up, either before a working diagnosis is made or before a diagnosis is finalized. As such, diagnostic stewardship typically involves modifying the diagnostic testing process. Unlike antimicrobial stewardship, most diagnostic stewardship interventions do not involve in-person expert guidance. Notably, however, the inclusion of in-person expert guidance (eg, infectious diseases consultation) in some diagnostic stewardship interventions can potentiate their effectiveness, especially with interventions designed to address complex or expensive diagnostic tests. Furthermore, diagnostic stewardship relies on process improvement (eg, how tests are collected and analyzed) or behavioral economics to nudge clinicians toward better use and interpretation of diagnostic tests (ie, checklists, defaults, and selective reporting). Because diagnostic stewardship strategies rely heavily on the laboratory and the electronic health record, microbiologists, phlebotomists, and information technology specialists may have a prominent or even leading roles in diagnostic interventions. Reference Miller, Binnicker and Campbell13 The success of diagnostic stewardship interventions relies significantly on how well they integrate into existing system processes and workflows.

Potential synergies between antimicrobial and diagnostic stewardship interventions

Diagnostic stewardship can be designed to be complementary to antimicrobial stewardship. Reference Dik, Poelman and Friedrich14,Reference Messacar, Parker, Todd and Dominguez15 In fact, many ASPs and infection prevention programs used diagnostic stewardship interventions well before the phrase “diagnostic stewardship” was coined. Infection prevention programs have recognized that poor specimen collection methods impact measures of healthcare-associated infections as determined through standardized surveillance definitions and influence certain clinical practices. Furthermore, ASPs have long recognized that appropriate antimicrobial use (ie, empiric selection and duration) requires accurate diagnosis. For example, convincing a clinician to order nitrofurantoin rather than ciprofloxacin to treat acute cystitis is only a “win” if the patient has a true infection and not asymptomatic bacteriuria. Too often, however, diagnosis is separate from antimicrobial stewardship interventions. Some pharmacists, particularly those without stewardship-specific training, report feeling less comfortable recommending discontinuation of antibiotics and therefore may defer to clinicians for diagnosis. Reference Broom, Plage, Broom, Kirby and Adams16–Reference Wong, Tay and Heng18 Diagnostic stewardship interventions thus provide a critically important opportunity to improve diagnosis and complement downstream antimicrobial stewardship activities. In fact, for some antimicrobial priorities, such as unnecessary antibiotic use for asymptomatic bacteriuria, diagnostic stewardship interventions are far more effective at reducing antibiotic overuse than antimicrobial stewardship interventions. Reference Vaughn, Gupta and Petty19

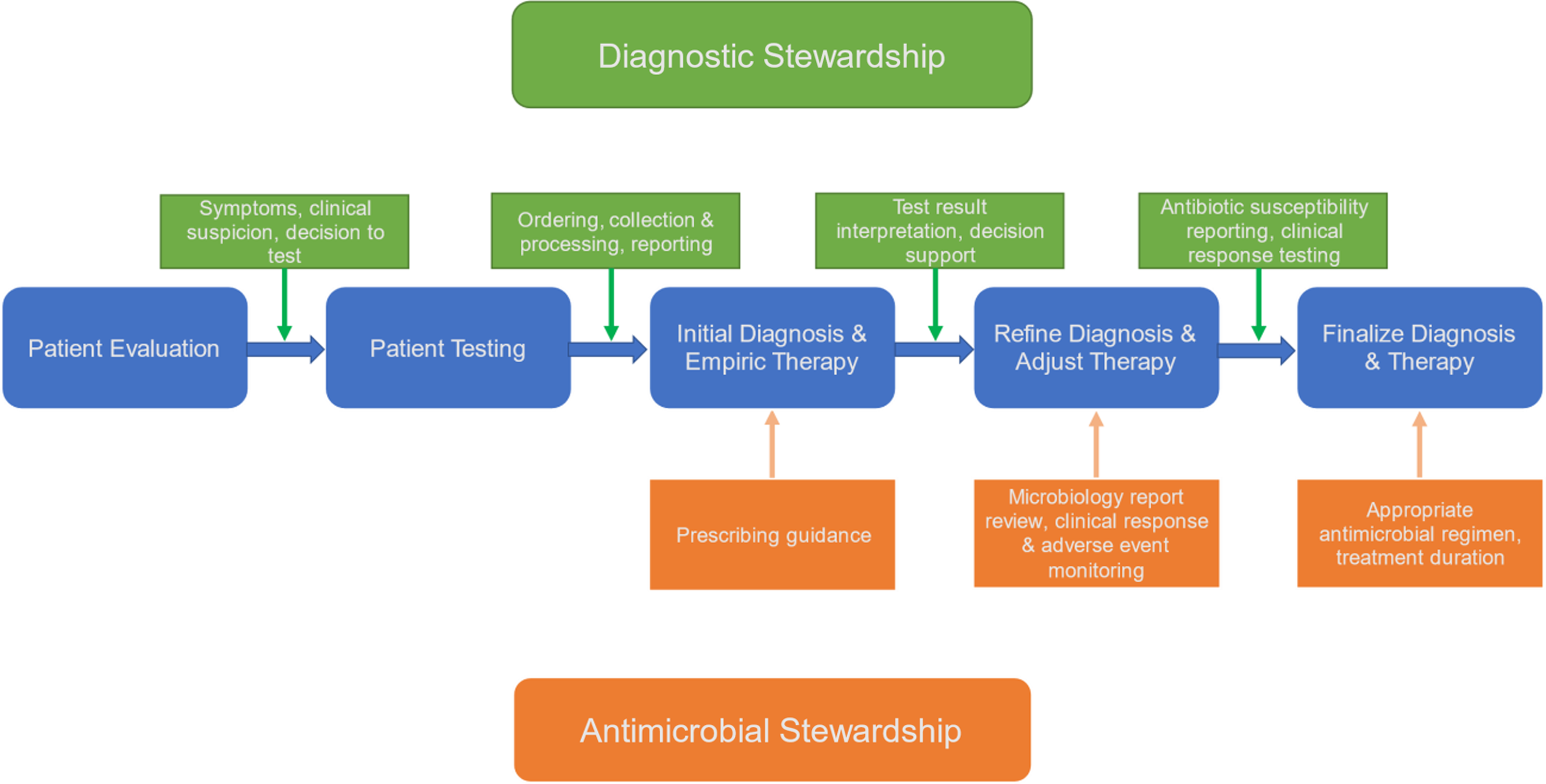

Although diagnostic stewardship interventions primarily target diagnostic testing and clinical decision making during the clinical evaluation of patients, these interventions can be incorporated at any point during the patient care pathway where diagnostic testing and reporting occurs (Fig. 1). For example, in a febrile patient, diagnostic stewardship can be helpful to inform antibiotic selection at multiple steps in the pathway: (1) In patient evaluation, clinical decision support (CDS) can help direct diagnostic testing towards appropriate patient populations in evidence-based scenarios given known risk factors and symptoms. (2) Patient testing can guide sampling of proper specimen with appropriate collection techniques, and improper or contaminated specimens can be rejected. (3) In initial diagnosis and empiric therapy, Gram stain and rapid polymerase chain reaction (PCR) results are reported with real-time decision support to assist in interpretation at the time of medical decision making. Reference Banerjee, Teng and Cunningham20 (4) In refining diagnosis and adjusting therapy, interim results with context or guidance can be reported (eg, “no MRSA isolated” or “no Pseudomonas isolated”). (5) In finalizing diagnosis and therapy, antimicrobial susceptibilities can be reported (eg, selective antibiotic susceptibility reporting).

Figure 1. Relationship between diagnostic stewardship (green) and antimicrobial stewardship (orange) on patient diagnosis and treatment.

Additionally, diagnostic stewardship and antimicrobial stewardship should be, and often are, used concomitantly to reach their common goals. For example, diagnostic stewardship and antimicrobial stewardship interventions can play complementary roles to reduce inappropriate urinalysis and urine-culture testing and treatment of bacteriuria in asymptomatic patients with indwelling urinary catheters. This is accomplished through a combination of CDS, best-practice advisory alerts, specimen rejection protocols, laboratory result reporting guidance, handshake stewardship, and audit and feedback.

Examples of diagnostic stewardship interventions that advance antimicrobial stewardship goals

To demonstrate how diagnostic stewardship can further the goals of antimicrobial stewardship, we illustrate how diagnostic stewardship can optimize prescribing during each of the “Four Moments of Antibiotic Decision Making.” 21 The Four Moments, created by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality as a tool to help clinicians make better antibiotic choices, consider 4 time points where antibiotic decision-making is critical: (1) “Does my patient have an infection that requires antibiotics?” (2) “Have I ordered the appropriate cultures before starting antibiotics? What empiric therapy should I initiate?” (3) “A Day or more has passed, can I narrow/stop antibiotic therapy?” (4) “What duration of therapy is needed for my patient’s diagnosis?” Each moment asks clinicians specific questions about antibiotic use during the various stages of clinical management. Since diagnosis impacts the answers, diagnostic stewardship interventions can be incorporated into each moment to enhance diagnostic and antibiotic stewardship. Examples for each moment can be found in Table 2.

Table 2. The Four Moments of Antimicrobial Stewardship with Examples of Correlating Diagnostic Stewardship Interventions for Managing Asymptomatic Bacteriuria and Bacteremia

Note. AS, antimicrobial stewardship; ASP, antimicrobial stewardship program; CDS, clinical decision support; CLABSI, central-line–associated bloodstream infection; CVC, central venous catheter; DS, diagnostic stewardship.

Moment 1: Does my patient have an infection that requires antibiotics?

Moment 1 is the clearest example of how diagnostic stewardship can influence antibiotic prescribing. Because this step of the diagnostic pathway usually involves the decision to order diagnostic testing, any diagnostic stewardship intervention that targets testing decision making can be applied here. Diagnostic questions that may be included during Moment 1 include “Should I order a diagnostic test to determine if my patient has an infection? If so, what is the appropriate diagnostic test?”

One example of a Moment 1 diagnostic stewardship intervention is using CDS to guide clinicians to select diagnostic tests based on pre-test probability, including risk factors, symptoms, and disease severity. To demonstrate this, CDS was used as a part of a diagnostic stewardship intervention implemented at a pediatric hospital to help clinicians identify patients suspected of central nervous system infections who qualify for rapid molecular diagnostic testing. This intervention resulted in significant improvements in antimicrobial use by providing faster results and shortening empiric therapy. Reference Messacar, Palmer and Gregoire22 Similarly, interventions to stop unnecessary diagnostic testing in patients without symptoms of an infection (or symptoms attributable to another cause) also belong in Moment 1 (eg, order-set hygiene, and best-practice advisories advising against or declining C. difficile testing if the patient is on laxatives). For example, a CDS algorithm implemented in a pediatric intensive care unit at a major academic medical center was instrumental in reducing the frequency of endotracheal aspirate cultures performed monthly by 41% without any significant changes in in-hospital mortality, length of stay, and 7-day readmissions. Reference Sick-Samuels, Linz and Bergmann23 Nudging is an incredibly useful tool during Moment 1, as demonstrated by a study in which replacing urine cultures with urinalyses in ED order sets decreased urine culture orders and subsequent treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria by 47%. Reference Munigala, Jackups and Poirier24

Moment 2: Have I ordered the appropriate cultures before starting antibiotics? What empiric therapy should I initiate?

Moment 2 asks whether appropriate cultures have been ordered before starting antibiotics. Because this moment refers to specimen collection and processing, it can be expanded to include steps to improve the selection, quality, and utility of the specimen which are essential in optimizing their analysis and interpreting their results. Reference Miller, Binnicker and Campbell13 Specific tenets on how infection-related specimens should be managed to enhance diagnosis have been described in guidance from the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Society for Microbiology. Reference Miller, Binnicker and Campbell13 Additional diagnostic questions to include in Moment 2 are “Is the specimen appropriately collected and stored? Is the specimen of the appropriate type and sufficient quality to be tested? How should the specimen be tested?”

Examples of diagnostic stewardship interventions for Moment 2 tend to focus more on processes. An example includes improving urine collection from patients with indwelling urinary catheters. Furthermore, discouraging clinicians from performing superficial swabbing of wounds for culture may prevent them from treating the contamination from surrounding skin flora. In certain scenarios, incorrectly obtained specimens or those with a high risk of misleading results (eg, urinalysis with many squamous epithelial cells or sputum with many oral flora) can be automatically rejected by the laboratory.

Moment 3: “Can I stop antibiotics? Can I narrow therapy?”

Moment 3 asks whether antibiotic therapy can be stopped or modified. Diagnostic test results are critical in this stage because clinicians often rely on the availability of those results, whether preliminary or final. For example, studies have shown that the absence of negative diagnostic tests (eg, no blood or respiratory samples were obtained) in adult patients with pneumonia makes clinicians hesitant to de-escalate. Reference Vaughn, Flanders and Snyder25 This is also a step in which the appearance of positive results (eg, urine culture in an asymptomatic patient) can trigger reflexive antibiotic prescribing. As such, an additional question for this moment is “What do the test results tell me about what I should do with my patient?”

When tests are available, diagnostic stewardship can be powerful during Moment 3. For patients who truly have infections, Moment 3 is when selective or cascade susceptibility reporting can prevent prescribers from using high-risk, excessively broad-spectrum, or ineffective antibiotics when an organism is susceptible to a safer and/or more effective antibiotic. Furthermore, interpretive guidance comments may be included to assist physicians in avoiding certain antibiotic regimens or considering consulting with an infectious disease specialist. For example, in a study by Musgrove et al, Reference Musgrove, Kenney and Kendall26 for patients with oral flora in their respiratory cultures (and thus no pathogenic bacteria identified), framing the results with the phrase “commensal respiratory flora only: No Staphylococcus aureus/MRSA or Pseudomonas aeruginosa” increased de-escalation of vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam from 30% before the intervention to 73% after the intervention. Reference Musgrove, Kenney and Kendall26 Screening patients with MRSA PCR of swabs of the nares can help clinicians avoid the need of or encourage de-escalation of MRSA-active antibiotic regimen in patients with pneumonia. Reference Carr, Daley, Givens Merkel and Rose27,Reference Willis, Allen, Tucker, Rottman and Epps28 Similarly, for patients for whom the diagnostic test often provides misleading information, diagnostic stewardship interventions include selective reporting or framing the results. An example of both selective reporting and framing results was reported by Leis et al. Reference Leis, Rebick and Daneman29 In a proof-of-concept study, discontinuation of routine reporting of positive urine-culture results accompanied with the laboratory report message, “The majority of positive urine cultures from inpatients without an indwelling urinary catheter represent asymptomatic bacteriuria. If you strongly suspect that your patient has developed a urinary tract infection, please call the microbiology laboratory,” led to a 36% reduction in antibiotic treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria. Additionally, real-time decision support using an infectious diseases–trained clinician to convey interpretations of critical test results along with patient-specific antimicrobial recommendations at the time of medical decision making has been a highly effective approach as well as acceptable by the end-user clinicians. Reference Banerjee, Teng and Cunningham20,Reference Messacar, Palmer and Gregoire22

Moment 4: “What is the duration of antibiotic therapy needed for my patient’s diagnosis?”

Moment 4 asks the question of antibiotic therapy duration. This final moment of antimicrobial stewardship occurs when the diagnostic process has concluded, and the patient has a final or definitive diagnosis. Too often, clinicians fail to reflect and stop antibiotic therapy even when an alternative nonbacterial cause has been discovered (eg, heart failure in a patient being treated for pneumonia or enterovirus detected in the cerebrospinal fluid of a patient with suspected meningitis Reference Ramers, Billman, Hartin, Ho and Sawyer30,Reference Drysdale and Kelly31 ). Thus, this is the final opportunity for diagnostic stewardship to impact clinical care. This may occur when a “diagnostic time-out” is incorporated with an “antibiotic stewardship” time-out at hospital discharge. Reference Giesler, Krein and Brancaccio32

Follow-up diagnostic testing can be considered to assess clinical response (eg, serial biomarkers in osteomyelitis or repeated blood cultures for S. aureus bacteremia) or ensure source control (eg, computed tomography after placing a percutaneous drain into an abscess). In some cases, biomarkers may be used to help determine when antimicrobial therapy may be stopped (eg, procalcitonin in critically ill patients with bacterial infections and sepsis). Reference Wirz, Meier and Bouadma33,Reference Jong, Oers and Beishuizen34 On the other hand, clinicians should be guided away from the use of certain laboratory tests (eg, urinalysis and urine culture) as tests of cure or overuse of imaging studies (eg, magnetic resonance imaging in vertebral osteomyelitis) in patients who displayed favorable clinical responses to appropriate courses of antibiotic therapy. As such, additional diagnostic questions during Moment 4 may include the following: Do the test results confirm that my patient has an infection? If so, what is the final diagnosis and treatment? Are there any follow-up diagnostic tests I should or should not perform?

Implementation considerations for diagnostic stewardship

Diagnostic stewardship interventions can create significant complexity and disruptions in clinical processes and workflow. To prevent disruptions, ASPs or healthcare quality improvement professionals seeking to implement a diagnostic stewardship intervention should first conduct a careful analysis to identify any system processes that could be affected. To inform these efforts, they should obtain input from end-user clinicians and other applicable stakeholders (eg, microbiologists, laboratory personnel, phlebotomists, infection preventionists, information technology specialists, healthcare administrators as well as infectious diseases physicians and pharmacists), and they should endeavor to optimize workflow to minimize disruption. Once an intervention has been designed and implementation planned, they should provide sufficient education to the affected end users (or engage champions to provide the education) to ensure a successful launch of the intervention. Reminders, such as posters, reference cards, and visual aids placed in work areas, can help reinforce the process changes and improve compliance, especially if the intervention does not involve automatic nudging or restricting test orders. Reference Fabre, Klein and Salinas35 Furthermore, diagnostic stewardship interventions should include measures to obtain regular feedback from ASPs and end users to troubleshoot and help continually modify the intervention to optimize stewardship and patient outcomes.

Although the goal of diagnostic stewardship is improving appropriate test use, this often is seen as restricting test use. Thus, one critical challenge for diagnostic stewardship is ensuring that diagnostic stewardship interventions are not seen to always reduce testing in situations where it is indicated and appropriate. For example, urine cultures generally should be discouraged in patients without urinary symptoms; however, in certain situations urine cultures should be obtained, such as in young infants, pregnant patients, or those undergoing invasive urologic procedures, even in the absence of symptoms. Reference Pantell, Roberts and Adams36,Reference Nicolle, Gupta and Bradley37 For this reason, planning ahead and creating balancing metrics (ie, metrics that measure potential harms for an intervention) are critical. For example, when planning to reduce urine cultures, one balancing metric could be hospital-onset bacteremia from a urinary source or failure to obtain urine cultures where indicated (ie, pregnant patients and febrile neonates). Ideally, prospective monitoring of patient-centered safety measures should occur along with review of aggregate data following implementation of a diagnostic stewardship intervention (eg, toxic megacolon after implementation of a C. difficile diagnostic stewardship intervention). Reference Madden, Weinstein and Sifri38 Multiple potential clinical indications exist for most diagnostic tests; consequently, the impact of diagnostic stewardship interventions may only be readily apparent after the intervention has been implemented. Creating exceptions to the interventions may add unnecessary complexity to already complex processes. Instead, it may be best to make alternative ordering processes specific to certain departments or clinicians (eg, different pathways for obstetrics vs medicine vs pediatrics).

Finally, when using nudging or choice architecture, it is essential to be thoughtful in design and implementation because a poorly designed intervention can work against clinicians and compromise trust and collaboration. Reference Vaughn and Linder39 Obstruction, dissension, and workarounds may result. The most common form of nudging is typically electronic CDS or reminders (ie, best practice advice or indication selection) because they can be (somewhat) easily set up in electronic medical record systems. When designing CDS or nudges, it is important to remember 4 key design principles: (1) the use of strategic defaults (prechecked items are more likely to be done but may lead to overuse), (2) the order within lists (first items are more likely to be selected), (3) framing (ie, providing context for the results), and (4) ease (easier things are more likely to be done). Reference Advani and Vaughn40 It is also important to use tools that interrupt workflow sparingly (eg, pop-up CDS windows) because the overuse of electronic reminders has led to “alert fatigue,” which has resulted in clinicians ignoring or overriding alerts. Reference Bilinskaya, Goodlet and Nailor41–Reference Dunn, Radakovich, Ancker, Donskey and Deshpande43 As such, thoughtful consideration is needed when electronic CDS reminders and tools are included as part of the diagnostic stewardship intervention. Equally importantly, successful diagnostic stewardship interventions should be routinely monitored to ensure they remain effective and needed and are removed if they are not.

In conclusion, making an accurate diagnosis that is based on appropriate diagnostic testing is critical to antibiotic stewardship. Therefore, ASPs and healthcare quality improvement professionals need to think upstream of prescribing to the diagnostic testing that often drives antibiotic overuse. Because antimicrobial and diagnostic stewardship share common goals, diagnostic stewardship can complement antibiotic stewardship, especially if there is collaboration across teams and proactive consideration of the effects of diagnostic stewardship interventions on both diagnostic testing and antibiotic use. With the rapid increase in new diagnostic tests, diagnostic stewardship will grow in importance for antibiotic stewardship. In summary, diagnostic stewardship is a critical tool for improving diagnosis and can be used to compliment ASP efforts to optimize antibiotic overuse.

Acknowledgments

We have endorsement from IDSA Diagnostics Committee, Society of Hospital Medicine, Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Conflicts of interests

Dr. Diekema reports consulting fees regarding development of molecular diagnostics from OpGen, Inc and a bioMerieux research contract for clinical trials of new antimicrobial susceptibility testing devices. Dr. Kisgen reports consulting fees from Shionogi & Company. Dr. Messacar reports a speaker honorarium paid by Medscape as an invited CME presenter on Diagnostic Stewardship. All other authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.