To the Editor—Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) is the most common healthcare-associated infection in the United States.Reference Magill, Edwards and Bamberg 1 In 2011, almost half a million infections and ~29,000 deaths were estimated to be associated with C. difficile.Reference Lessa, Mu and Bamberg 2 Timely testing and treatment is critical for improving outcomes and reducing transmission.Reference Buckel, Avdic, Carroll, Gunaseelan, Hadhazy and Cosgrove 3 Given the high rate of asymptomatic C. difficile carriage, appropriate testing is also essential.Reference Alasmari, Seiler, Hink, Burnham and Dubberke 4 In healthcare settings, C. difficile colonization is reportedly 5 to 10 times more common than CDI and other noninfectious causes of diarrhea.Reference Polage, Gyorke and Kennedy 5 , Reference Polage, Chin, Leslie, Tang, Cohen and Solnick 6

Unformed stools due to laxative use are often submitted for CDI testing, although these specimens are not appropriate for CDI diagnosis. Recent laxative use has been reported in up to 44% of CDI tested specimens.Reference Buckel, Avdic, Carroll, Gunaseelan, Hadhazy and Cosgrove 3 , Reference Tehrani and Seville 7 , Reference Rineer, Dizon, Logan and Hsu 8 Interventions to reduce the testing of inappropriate specimens, including those due to laxative use, have led to a reduction of CDI rates and treatment.Reference Truong, Gombar and Wilson 9 We further examined the relationship between laxative use and patients who tested positive for CDI.

A retrospective study was conducted at a 537-bed teaching community hospital and included hospitalized patients who tested positive for CDI in 2014 and 2015. Testing for CDI comprised an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) for glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) and an EIA for detection of toxin A/B (C. diff Quik Check Complete, Alere, Waltham, MA). If the GDH test was positive and the EIA for the toxin A/B was negative, a confirmatory polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay (Xpert C. difficile, Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA) was performed. Clostridium difficile infection was diagnosed using either GDH-positive and toxin-positive or PCR-positive laboratory results.

Patients who received laxatives up to 24 hours prior to positive CDI testing were identified. Laxatives included docusate sodium, senna, polyethylene glycol, bisacodyl, milk of magnesia, sodium polystyrene sulfonate, and lactulose. Sodium polystyrene and lactulose were considered laxatives if the indications for use were neither hyperkalemia nor hepatic encephalopathy, respectively. Physician and nursing notes were reviewed to determine whether diarrhea (≥3 unformed stools over 24 hours) resolved within 24 hours of positive CDI testing. The medication administration record was reviewed to determine whether laxatives were administered for greater than 24 hours after positive testing. Validation procedures were conducted for >10% of the study population to ensure reviewer consistency.

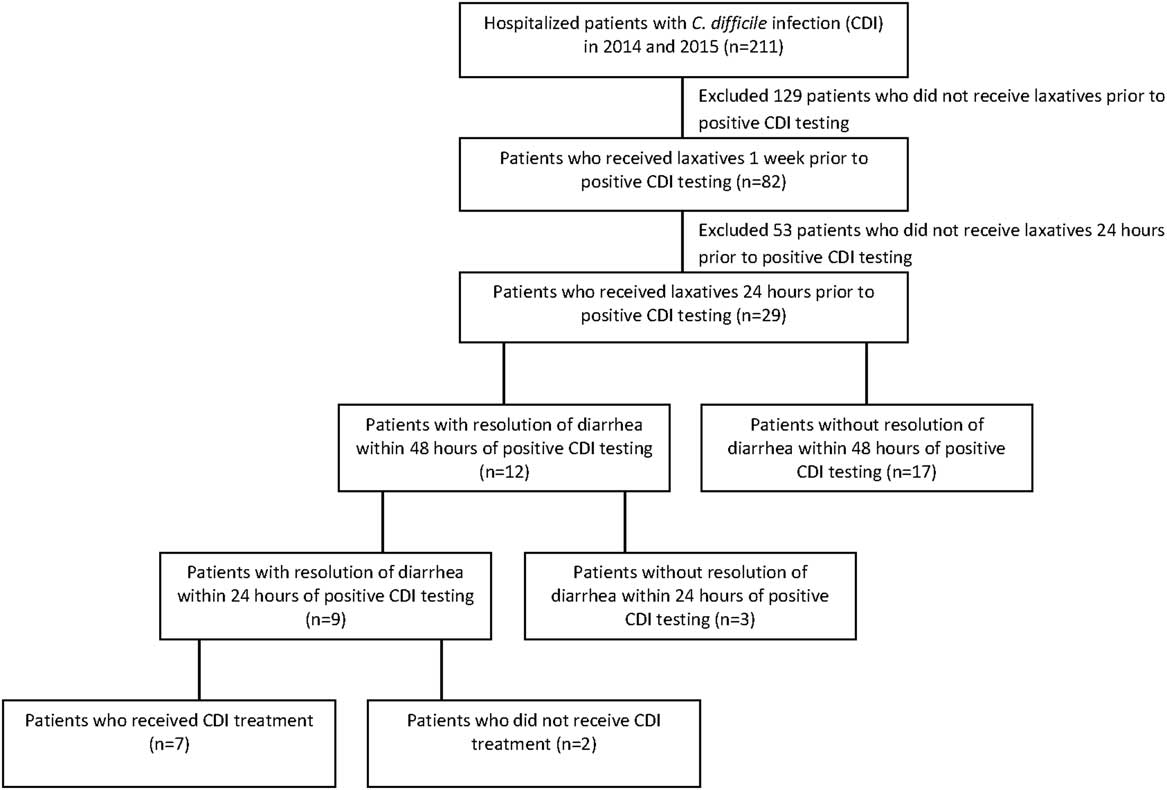

A total of 211 patients with CDI were included in the study. Overall, 82 patients (39%) had received laxatives within 7 days prior to positive CDI testing. Of these, 29 (14%) had received laxatives in the 24 hours prior to positive testing (Table 1). In the 24 hours prior to positive testing, 11 patients (38%) received 1 laxative; 12 patients (41%) received 2 laxatives; 4 patients (14%) received 3 laxatives; and 2 patients (7%) received 4 laxatives. The most commonly administered laxatives were docusate sodium (72%), polyethylene glycol (41%), senna (38%), and bisacodyl (17%). Furthermore, 15 patients (52%) continued to receive laxatives for >24 hours after positive CDI testing.

TABLE 1 Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Hospitalized Patients with Laxative Use Within 24 Hours of Positive Testing for Clostridium difficile

NOTE. EIA, enzyme immunoassay; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

a Unless units are otherwise specified.

Of the 29 patients, 12 (41%) had resolution of diarrhea within 48 hours of positive CDI testing, including 9 (31%) who had resolution within 24 hours. Of the 9 patients who had resolution of diarrhea within 24 hours, 2 patients (22%; both toxin EIA−/PCR+) did not receive CDI treatment, and 7 patients (78%; 3 toxin EIA+, 4 toxin EIA−/PCR+) received CDI treatment.

Other studies have reported the association of laxative administration with testing for CDI.Reference Buckel, Avdic, Carroll, Gunaseelan, Hadhazy and Cosgrove 3 , Reference Tehrani and Seville 7 , Reference Rineer, Dizon, Logan and Hsu 8 , Reference Truong, Gombar and Wilson 9 We reviewed this association for those patients who tested positive for CDI. Surprisingly, 82 patients (39%) received laxatives within 1 week of CDI diagnosis; 29 (14%) received laxatives (usually ≥2) within 24 hours of positive testing. Despite positive results for CDI, 15 patients (52%) continued to receive laxatives for >24 hours after diagnosis.

FIGURE 1 Laxative Use Among 211 Hospitalized Patients with Positive Testing for Clostridium difficile.

It is critical for clinicians to distinguish patients with clinically significant diarrhea from those with diarrhea due to laxatives. Of the 29 patients who received laxatives 24 hours prior to CDI diagnosis, 12 patients (41%) had resolution of diarrhea within 48 hours including 9 (31%) with resolution in 24 hours. These findings illustrate that diarrhea in the setting of laxative use and positive CDI testing may be of noninfectious etiology.Reference Polage, Solnick and Cohen 10 As further supporting evidence, 2 patients (7%) had resolution of diarrhea without any CDI treatment.

Asymptomatic colonization among hospitalized patients with C. difficile may be as high as 21%.Reference Alasmari, Seiler, Hink, Burnham and Dubberke 4 Appropriate testing for CDI is critical given the inability of current testing to distinguish between asymptomatic carrier and disease state. Truong et alReference Truong, Gombar and Wilson 9 recently reported a significant decrease in C. difficile test utilization from 208.8 to 143 tests per 10,000 patient days and a decrease in healthcare facility-onset CDI of >25% (ie, from 13.0 to 9.7 cases per 10,000 patient days) using real-time electronic data to enforce laboratory testing criteria, which they defined as the presence of diarrhea and absence of laxative use in the prior 48 hours.Reference Truong, Gombar and Wilson 9

In addition to improving testing cascades for CDI by limiting specimens from patients receiving laxatives, education must also engage the nursing staff. Nurses are integral in the stewardship of specimen collection for CDI because they are likely more aware of when laxatives are administered, especially since laxatives are often ordered as needed and through order sets.

Further interventions are urgently needed to improve testing stewardship for CDI, as restricting collection to patients not on laxatives represent potential opportunities for significant impact. Furthermore, providers must also consider receipt of other agents (eg, tube feeds, oral contrast) that may cause noninfectious diarrhea when considering testing for CDI.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial support: No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Potential conflicts of interest: Anurag N. Malani, MD, serves as a consultant to Vizient.

All other authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.