Introduction

Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) is a leading cause of health care–associated infections, resulting in substantial morbidity and mortality worldwide. Reference Guh, Mu and Winston1,Reference Leffler and Lamont2 Asymptomatic individuals colonized with C. difficile do not display signs of CDI, but can act as reservoirs for transmission. Asymptomatic C. difficile colonization occurs in 3%–21% of adults in acute care hospitals. Reference Crobach, Vernon and Loo3 Rates are lower when excluding non-toxigenic strains, which are not associated with CDI progression. About 22% of individuals colonized with toxigenic strains progress to CDI (RR 5.86, 95% confidence interval (CI), 4.21–8.16), but incidence varies significantly. Reference Zacharioudakis, Zervou and Pliakos4 The risk factors that lead to progression from carrier state to acute infection are not well characterized, with limited studies to date specifically examining the population of individuals colonized with toxigenic C. difficile. Reference Crobach, Vernon and Loo3,Reference Shim, Johnson and Samore5–Reference MacKenzie, Murillo and Bartlett9 Identifying factors associated with progression to CDI among patients colonized with toxigenic C. difficile is imperative given the role asymptomatic carriage plays. Studying this population can inform targeted interventions and identify prevention strategies to prevent CDI progression. At our institution, a universal rectal swab polymerase chain reaction (PCR) surveillance test is performed on all adult patients upon admission to determine toxigenic C. difficile colonization status. Colonization status is documented in the electronic medical record (EMR) and patients are placed on contact enteric precautions per institutional protocols. This practice, adopted from findings that demonstrated the utility of universal screening for mitigating C. difficile transmission, was implemented as part of our infection prevention strategies. Reference Longtin, Paquet-Bolduc and Gilca10 Among a cohort of colonized patients, we attempted to study the incidence, characteristics, and risk factors for progression to CDI.

Methods

Study design, definitions & population

We conducted a nested case-control study of patients with positive C. difficile admission screening at the University of California Davis Medical Center between November 2017 and December 2020. Patients were identified through an EMR-generated report. Patients ≥ 18 years old with a positive C. difficile toxin PCR on admission were included. Patients were excluded if they had any documented history of CDI identified through EMR or external medical records, presented with diarrhea or other gastrointestinal symptoms consistent with community-onset CDI, or if their PCR screen was performed > 24 hours after admission. Patients with prior CDI were excluded to minimize confounding impact on future CDI risk and reduce misclassification of residual DNA from recent infection as colonization. Patients hospitalized < 24 hours, pregnant, with an absolute neutrophil count < 500, or with a history of rectal surgery were excluded as they do not routinely undergo screening at our institution. Exclusions were applied during initial testing and chart review. Patients who developed hospital-onset (HO-CDI) were selected in a 1:3 ratio to toxigenic C. difficile colonized patients who did not develop HO-CDI, matched by PCR test date to control for temporal changes, ensuring same-month admissions. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Asymptomatic C. difficile colonization was defined as a positive C. difficile rectal swab PCR without CDI symptoms. CDI was defined as 1) diarrhea (≥ three loose stools within 24 hours) without any other etiology and with a positive C. difficile toxin enzyme immunoassay (EIA); 2) pseudomembranous colitis on colonoscopy; or 3) histopathologic diagnosis. PCR-positive/toxin-negative samples were not routinely retested unless clinical suspicion for CDI remained high. HO-CDI was defined as CDI with symptoms appearing ≥ 72 hours after admission. Incidence was calculated using proportional retention rates (63% for cases, 77% for controls) and applied to the total screened population to estimate the retained cohort. HO-CDI incidence was calculated as the proportion of retained patients who developed HO-CDI. Detailed calculations are in the supplementary material (Appendix S1).

The primary outcome was HO-CDI incidence, and we aimed to identify risk factors associated with development of HO-CDI. Secondary outcomes included admission all-cause mortality, hospital length of stay (LOS), and discharge disposition.

Clinical data collection

Data collected included baseline demographics, comorbidities, admission origin (home, transfer from an outside hospital, or admission from a skilled-nursing facility, long-term care, or rehabilitation center), recent hospitalization, surgical history, medication use (opioids, proton-pump inhibitors [PPI], immunosuppressants), antibiotics received within 90 days prior to admission and during hospitalization up to HO-CDI diagnosis, antibiotic class, hospital and ICU LOS, and antibiotics received during admission until HO-CDI diagnosis. Prior antibiotic use was identified through chart review within our healthcare system, including linked outpatient dispense reports and external records accessed via the Care Everywhere network. For non-HO-CDI, LOS reflects total hospitalization.

Laboratory assays

Colonization status was detected via rectal/fecal swab tested for the tcdB gene using PCR (Xpert C. difficile test; Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA). Testing for CDI was performed on unformed stool samples using a two-step algorithm; glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) testing followed by confirmatory EIA (C. Diff Quik Chek Complete; TechLab, Blacksburg, VA), consistent with guideline-recommended algorithms by performing a highly sensitive test first, followed by a highly specific test. Reference McDonald, Gerding and Johnson11

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics characterized the study sample. Categorical variables were summarized by frequencies and percentages and compared using the χ2 test or Fischer’s exact test. Continuous variables were summarized by means and standard deviations (SD) and compared using logistic regression. To identify factors associated with HO-CDI, bivariate and multivariable Cox proportional hazard models were performed to estimate unadjusted and adjusted associations, respectively. To select factors independently associated with HO-CDI, covariates with a P-value < .10 in the bivariate analysis and/or factors identified by Poirier et al. were included in the multivariable Cox model. Reference Poirier, Gervais and Fuchs8 Individual antibiotic classes were excluded from regression models due to multicollinearity, multiplicity, and limitations in assessing antibiotic effects. At-risk antibiotics were defined as penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems, quinolones, macrolides, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or clindamycin, based on their known association with subsequent CDI and continuing prior work by Poirier et al. Reference Poirier, Gervais and Fuchs8 The following risk factors were included in the model regardless of P-value, due to previously reported associations with CDI: age, opioid use, and PPI use. Reference Poirier, Gervais and Fuchs8,Reference Predrag12–Reference Dubberke, Yan and Reske14 A time-dependent covariate for the time to first dose of an at-risk antibiotic was included in the Cox model. Unadjusted/crude hazard ratios (HRs) and adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) with 95% CI were computed. CI and P-values were not adjusted for multiplicity. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and BlueSky Statistics version 7.40 software (BlueSky Statistics LLC, Chicago, IL).

Results

Characteristics of Clostridioides difficile colonized patients

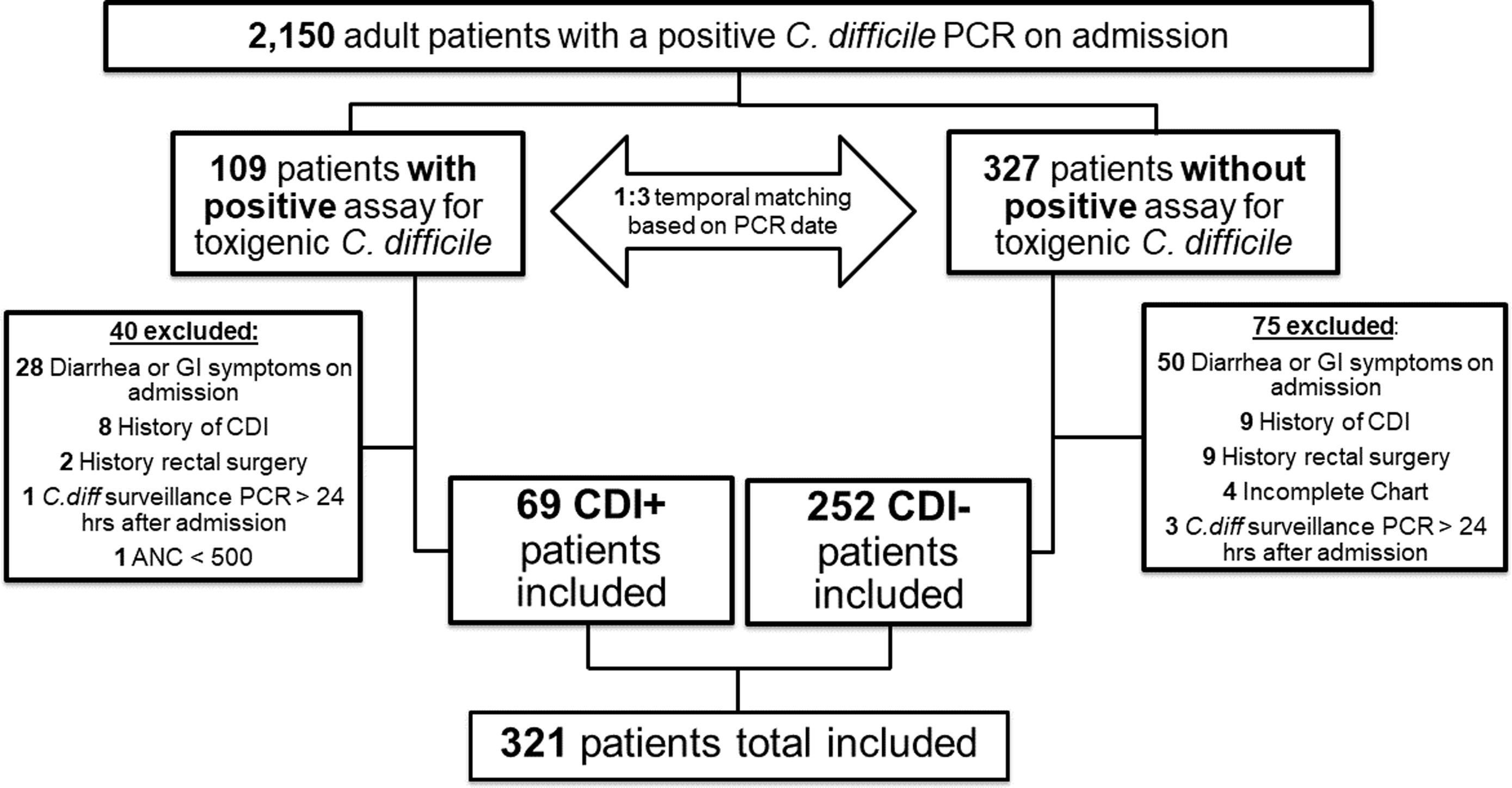

During the study period, 57,468 patients were screened and 2,150 (3.7%) were colonized with toxigenic C. difficile via rectal PCR swabs. Among them, 109 patients were diagnosed with CDI based on symptoms and a positive EIA toxin assay. These cases were matched 1:3 to 327 EIA toxin-negative or untested patients by PCR test date. After exclusion, 321 patients comprised the final cohort (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics by CDI status are in Table 1. The mean age was 64 years (SD 16.1), 45% were female, and the average hospital LOS was 11.9 days (SD 20.7). Most patients (70.1%) were admitted from home, 37.1% to the ICU on admission, and 61.7% had prior hospitalization within six months. Additionally, 78.8% received antibiotics during admission.

Figure 1. Study flow diagram. UC Davis Medical Center, November 2017 to December 2020. Abbreviations: PCR, polymerase chain reaction; C. difficile, Clostridioides difficile; CDI, Clostridioides difficile infection; GI, gastrointestinal; ANC, absolute neutrophil count.

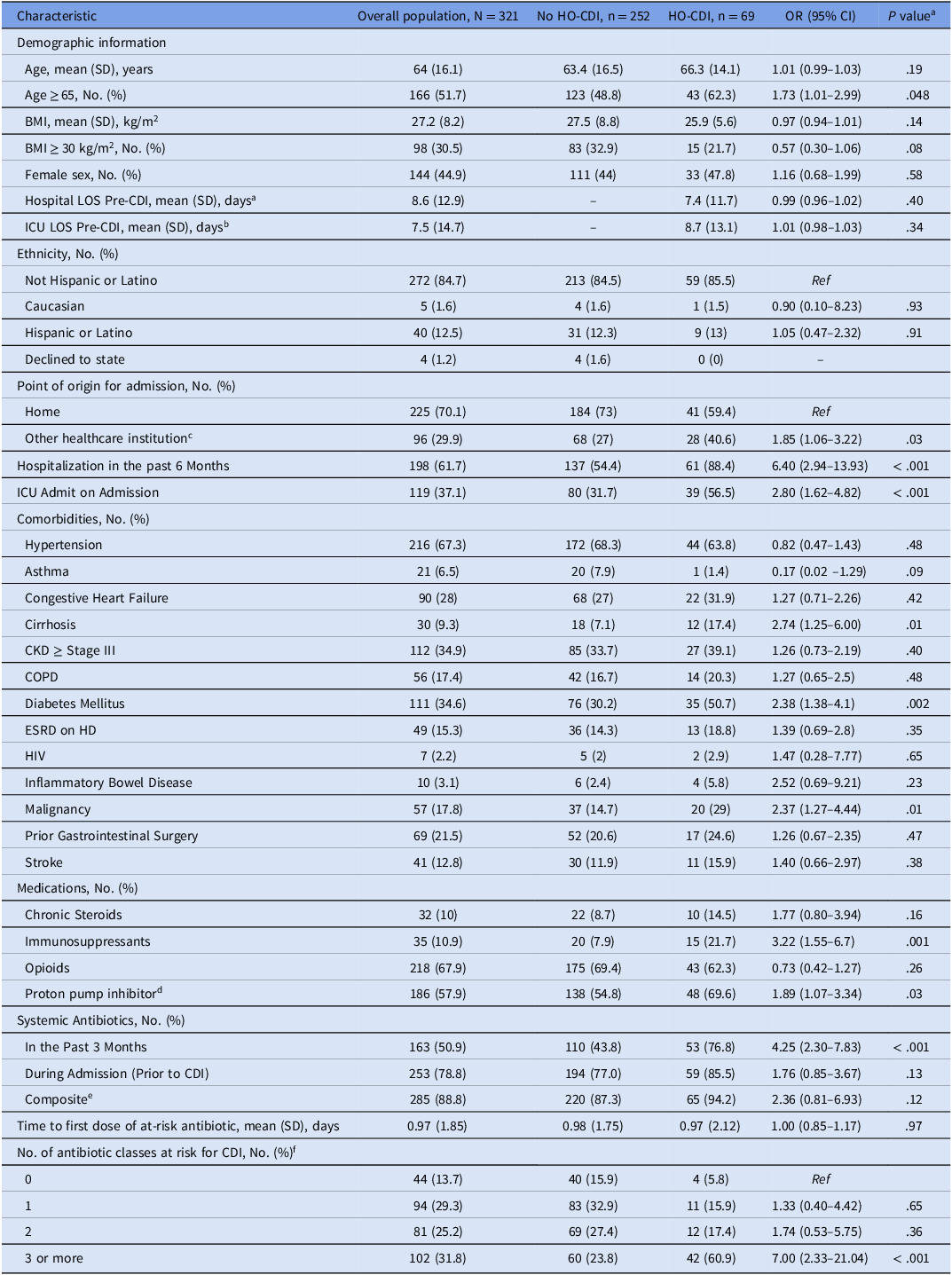

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of patients colonized with Clostridioides difficile

Abbreviations: HO-CDI, Hospital onset Clostridioides difficile infection; CI, confidence interval; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; HD, hemodialysis; HR, hazard ratio; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; No, number; PCN, penicillin; Ref, reference category; SD, standard deviation.

a P-values are not adjusted for multiplicity.

b Compared to total mean LOS in No HO-CDI group since CDI did not occur.

c Defined as a transfer from an outside hospital, or admission from a skilled-nursing facility, long-term care, or rehabilitation center.

d Includes if patient was taking prior to admission or during admission.

e Includes antibiotics received in the past 3 months prior to admission and during admission.

f Includes all penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems, quinolones, macrolides, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and clindamycin.

Patient outcomes

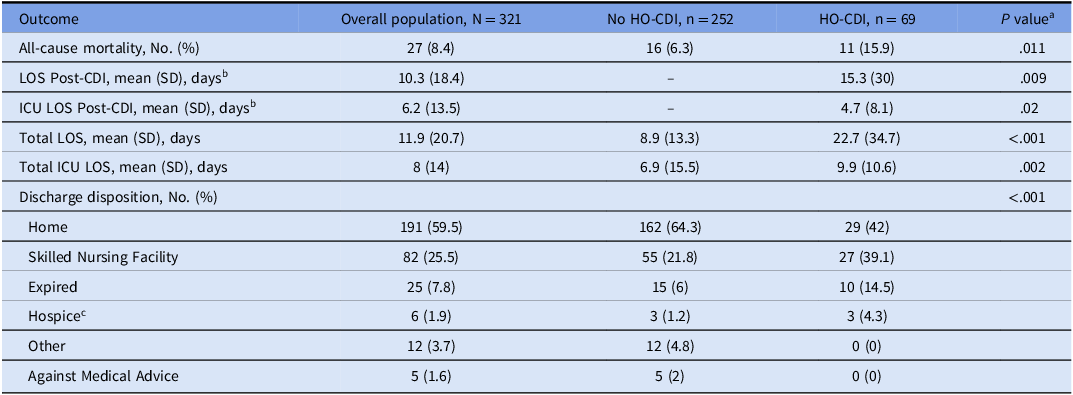

Among 2,150 total colonized patients, 69 developed HO-CDI following screening and exclusion, resulting in an estimated incidence of 4.2% (Table 2). The median time to diagnosis of HO-CDI was 7.4 (SD 11.7) days and all-cause mortality during admission was higher in HO-CDI patients (15.9% vs 6.3%; P = .011). Hospital LOS was longer in the HO-CDI group (22.7 vs 8.9 days; P < .001), and they were less often discharged home (42.0% vs 64.3%; P < .001).

Risk factors associated with CDI

Bivariate analysis showed HO-CDI patients were more often ≥ 65 years (62.3% vs 48.8%; P = .048), admitted from healthcare institutions (40.6% vs 27%; P = .03), admitted to ICUs at baseline (56.5% vs 31.7%; P < .001), and hospitalized in the past six months (88.4% vs 54.4%; P < .001). They were also more likely to have cirrhosis (17.4% vs 7.1%, P = .01), diabetes (50.7% vs 30.2%, P = .002), malignancy (29% vs 14.7%, P = .01), and to have received the following medications: immunosuppressant prior to admission (21.7% vs 7.9%, P = .001), PPIs (69.6% vs 54.8%, P = .03), antibiotics three months prior to admission (76.8% vs 43.8%, P < .001), and ≥ three at-risk antibiotic classes during admission (60.9% vs 23.8%, P < .001). Receipt of antibiotics during hospital stay (85.5% vs 77.0%, P = .13), LOS prior to HO-CDI, age, and inflammatory bowel disease were not associated with an increased risk of HO-CDI.

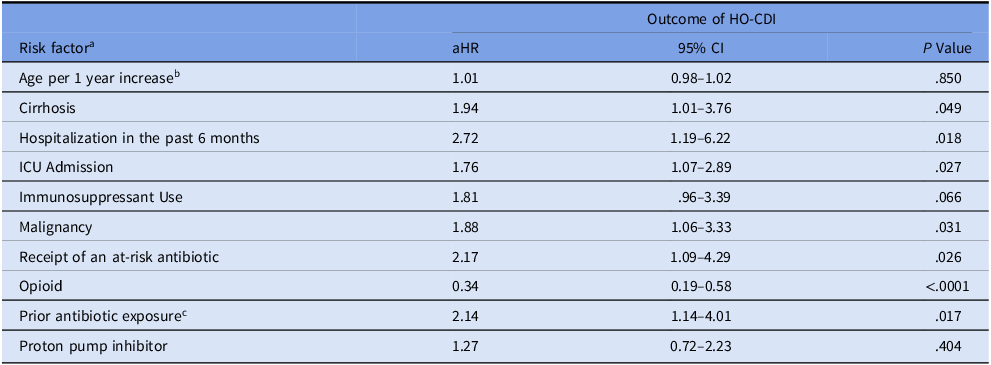

The multivariable Cox model (Table 3) identified the following as significantly associated with progression to HO-CDI: cirrhosis (aHR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.01–3.76; P = .049), hospitalization in the past six months (aHR, 2.72; 95% CI, 1.19–2.22; P = .026), ICU admission (aHR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.07–2.89; P = .027), malignancy (aHR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.06–3.33; P = .031), increasing number of at-risk antibiotic classes (aHR per each additional class, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.09–4.29; P = .026), and prior antibiotics (aHR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.14–4.01; P = .017). Notably, opioid use was associated with a significantly lower risk of progression to HO-CDI (aHR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.19–0.58; P < .0001). Age per year increase, immunosuppressants, and PPIs were not statistically significant.

Table 2. Outcomes of patients colonized with hospital-onset Clostridioides difficile

Abbreviations: HO-CDI, Hospital onset Clostridioides difficile infection; CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; No, number; SD, standard deviation.

a P-values are not adjusted for multiplicity.

b Compared to total mean LOS in No HO-CDI group.

c Two of these patients subsequently expired prior to leaving the hospital.

Table 3. Multivariable-adjusted cox proportional hazards model of risk factors associated with hospital-onset Clostridioides difficile infection among colonized patients

Abbreviations: aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; HO-CDI, Hospital onset Clostridioides difficile infection; CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit.

a All risk factors on admission or prior to CDI onset.

b Per one year increase.

c In the past 3 months.

All other factors are binary, ie, presence vs others. Antibiotic was coded as time-varying covariate/indicator during follow-up time; ie, 0 before receipt and 1 after receipt.

Detailed antibiotic data is available (Supplement Fig S1.) but should be cautiously interpreted due to potential confounding and collinearity with other risk factors and multiplicity. For example, composite metronidazole use was associated with increased HO-CDI risk on bivariate analysis, but on further review was almost always used in conjunction with other high-risk antibiotics like ceftriaxone or fluoroquinolones.

Discussion

Our study identified several CDI risk factors among colonized patients, confirming associations from prior studies. Reference Lin, Hung and Liu6–Reference MacKenzie, Murillo and Bartlett9 Prior antibiotic exposure and the number of at-risk antibiotic classes used were major risk factors. Modifying antibiotic selection, particularly by reducing high-risk antibiotic use, may reduce CDI incidence. Reference Baur, Gladstone and Burkert15–Reference Stephenson, Lanzas and Lenhart17 This is a modifiable risk that can be an effective intervention for stewardship programs to target colonized patients. Notably, 78.8% of colonized patients received antibiotics during hospitalization, a rate higher than the reported ∼50% in hospitalized patients. Reference Magill, O’Leary and Ray18 This underscores the need for stewardship efforts to minimize unnecessary antibiotic use and reduce progression to HO-CDI in this high-risk population.

Bivariate analysis found that patients ≥ 65 years were more likely to progress to CDI. However, similar to recent findings, multivariate analysis did not show increasing age as a CDI risk factor, despite it being a common predictor in non-screened populations. Reference Leffler and Lamont2,Reference Lin, Hung and Liu6 This adds to growing evidence that age may be associated with CDI due to higher colonization risk, rather than an increased risk of progression to CDI post-colonization. Reference Poirier, Gervais and Fuchs8,Reference Riggs, Sethi and Zabarsky19,Reference Alasmari, Seiler and Hink20

The association between C. difficile colonization and CDI in the ICU has shown mixed results in studies. Reference MacKenzie, Murillo and Bartlett9,Reference Tschudin-Sutter, Carroll and Tamma21–Reference Mi, Bao and Xiao23 Our analysis found that baseline ICU admission was independently associated with progression to HO-CDI in colonized individuals, even after controlling for other variables. ICU patients pose a challenge to stewardship programs due to acuity of illness, often necessitating the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics and hesitancy to de-escalate. Reference Wunderink, Srinivasan and Barie24,Reference Pickens and Wunderink25 Nevertheless, our findings indicate that such efforts are crucial in this population due to their elevated risk of CDI.

As commonly observed, immunosuppressant use and malignancy were associated with progression to HO-CDI. Reference Donnelly, Wang and Locke26–Reference Paudel, Zacharioudakis and Zervou28 These populations are vulnerable due to altered immune responses, prophylactic antibiotics, frequent hospitalizations, and microbiome disruption. Reference Donnelly, Wang and Locke26–Reference Paudel, Zacharioudakis and Zervou28 Notably, malignancy remained a significant risk factor after adjustment. Given the high incidence and poor outcomes, further studies are needed to determine whether certain populations with toxigenic C. difficile colonization, such as those with malignancy, might benefit from primary CDI prophylaxis. The role of oral vancomycin prophylaxis remains controversial due to its potential to disrupt the microbiome, warranting careful consideration of its risks and benefits, though fidaxomicin has shown potential for primary prophylaxis in non-screened, high-risk stem cell transplant patients. Reference Mullane, Winston and Nooka29

Studies have linked PPI use to CDI, potentially due to reduced gastric acid suppression leading to loss of protective effects or alternations in gut microbiota. Reference D’Silva, Mehta and Mitchell30–Reference Kachrimanidou and Tsintarakis32 However, the American College of Gastroenterology advises against discontinuing PPIs in CDI patients if indicated, given the relatively lower risk versus other factors. Reference Kelly, Fischer and Allegretti33 We found that PPI use (prior to or during admission) was not independently associated with progression to CDI. Despite this, PPI stewardship may still represent a valuable intervention, as studies suggest PPIs are unnecessary in over half of CDI cases though further validation is needed. Reference Choundhry, Soran and Ziglam34

Prior studies have linked recent hospitalization to both increased C. difficile colonization and infection at admission. Reference Dubberke, Reske and Seiler35,Reference Miller, Sewell and Segre36 In our study, hospitalization within the past six months was independently associated with progression to CDI in colonized patients. Patients with frequent healthcare-associated exposures may have elevated CDI risk due to unaccounted comorbidities, and the context of colonization exposure may serve as a surrogate for severity of illness.

Our study identified cirrhosis as a risk factor for CDI, consistent with prior findings in colonized patients. Reference Poirier, Gervais and Fuchs8 Cirrhosis may increase CDI risk due to use of antibiotics for treatment or prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, PPI use, frequent hospitalizations, and gut microbiome alterations. Reference Dotson, Aitken and Sofjan37 Notably, cirrhosis remained a significant risk factor after adjusting for these confounders. However, the impact of lactulose was not assessed and may have influenced the observed association.

The relationship between opioid use and CDI progression in colonized patients has yielded mixed results. In our study, opioid use was associated with a reduced risk of CDI, conflicting with Poirier et al. findings of increased risk. Reference Poirier, Gervais and Fuchs8 The reason for this difference, despite similar study designs, is unclear but raises questions about the association’s veracity. Patients with opioid use disorder, particularly those with opioid-associated constipation or withdrawal treatment, may be less likely to undergo testing, potentially leading to an underestimation of CDI incidence.

This study builds on previous work in the toxigenic C. difficile colonized population. Lin et al assessed 86 medical ward patients, 14 of whom developed CDI, identifying diabetes, PPI use, and exposure to multiple antibiotic classes as risk factors. Reference Lin, Hung and Liu6 Poirier et al assessed 513 carriers admitted to their hospital, of which 39 developed CDI, and found associations with hospital LOS, cirrhosis, probiotics, opioids, and the number of at-risk antibiotic classes. Reference Poirier, Gervais and Fuchs8 The strengths of our study, which builds upon this literature, includes its larger sample size - the largest cohort to date, a broad sample population, use of a highly specific diagnostic testing algorithm, use of antibiotic as a time-varying covariate, and evaluation of hospital LOS as a risk factor rather than an outcome. Poirier et al’s diagnostic approach, which involved only a one-step PCR-based test or a compatible clinical illness in colonized individuals (15% of CDI cases), may have overestimated CDI incidence (7.6% vs 4.2%). Reference Poirier, Gervais and Fuchs8 Prior studies suggest that the clinical course of PCR-positive, toxin-negative cases often mirrors that of non-CDI diarrhea patients. Reference Polage, Gyorke and Kennedy38,Reference Hogan, Hitchcock and Frost39

There are important limitations to this study. Case-control studies are well-suited for exploring associations but may not provide unbiased estimates of population-based parameters and outcomes. The retrospective design also introduces well known potential biases. Misclassification is inherent to CDI diagnosis, given the imperfect sensitivity and specificity of all testing algorithms, and in our study some toxin-negative patients may have had undiagnosed CDI. At our institution, GHD+/toxin- results are reported as negative, so some GDH+/toxin- patients may have been included in the control group if they met inclusion criteria. This dichotomous reporting of CDI test results as “positive” or “negative” limits the ability to evaluate the clinical significance of GDH+/toxin- results, potentially leading to misclassification. No specific steps were taken to mitigate this, a limitation reflecting the inherent challenges of CDI diagnosis in practice. Nevertheless, both empiric treatment for CDI in colonized patients and CDI testing solely due to colonization are rare at our institution, and CDI testing due to colonization is strongly discouraged through clinical decision support. Furthermore, upon review no controls received CDI treatment during admission, supporting low clinical suspicion for CDI. We did not assess risk adjustment scores (eg, Charlson Comorbidity or Elixhauser Comorbidity Index), which could better estimate the impact of comorbidities. We were unable to evaluate antimicrobial exposure by number of doses or duration, limiting our ability to assess these effects on progression to CDI. Prior antibiotic use was identified through chart review, including linked outpatient pharmacy dispense reports and external records from outside institutions. However, this approach may not have captured all external antibiotic use, particularly for patients without linked records, potentially underestimating exposure. Patients with neutropenia or prior rectal surgery, populations potentially at increased risk for HO-CDI, were also excluded from screening limiting applicability to these groups. Lastly, generalizability may be limited, as this study was conducted at a center performing universal C. difficile screening on all admitted patients, a practice that may not be feasible at other institutions

This study provides important implications for hospitals developing infection control policies aimed at reducing HO-CDI in patients colonized with toxigenic strains. The identified risk factors, including patient-specific comorbidities and modifiable medication-related risks, can be easily identified and inform the development of a scoring system. However, until such system is prospectively validated, it is difficult to ascertain how best stewardship programs can intervene on these identified risks. Furthermore, many institutions have developed CDI scoring systems that perform poorly when externally validated. Reference Perry, Shirley and Micic40 These points highlight the challenge of CDI prevention and underscore the need for institutions to locally validate their own patient-specific risk factors.

Conclusion

Progression to HO-CDI occurred in 4.2% of toxigenic C. difficile colonized patients at our institution. This study highlights several factors associated with progression to CDI among colonized patients that stewardship programs can potentially target to decrease the risk of progression to HO-CDI. Given the significant risk of HO-CDI in these individuals, particularly those identified with risk factors, further investigation into the utilization of tailored stewardship interventions or primary prophylaxis is warranted.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2025.4

Financial support

H.B. was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant [grant number UL1 TR001860].

Competing interests

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.