If the past—as the novelist L. P. Hartley suggested—is indeed “a foreign country,” David Lowenthal will be remembered as one of its most intrepid modern explorers, mapping its nostalgic landmarks, warning us of its lingering dark shadows, and alerting us to the paradoxical relationship between the pace of social change and the depth of the public’s fascination, even obsession, with “roots.” David’s best-known works, The Past Is a Foreign Country (1985) and The Past Is a Foreign Country—Revisited (2015) remain foundational texts for historians, archaeologists, and heritage scholars who have come to recognize—many of them from David’s wise and wry insights—that our appreciation of the significance of monuments and the relics of past cultures has at least as much to do with the contemporary “us” as it does with the historical “them.”

David was a master of the vivid antiquarian anecdote, the cultural detail, the obscure newspaper clipping that plainly showed how the entanglement of past and present was—to put it in contemporary terms—a feature, not a bug of the historical enterprise. The rise of the modern “heritage industry” and the increasing use of historical and archaeological symbols in global political discourse provided twin foci for his voluminous body of lectures, articles, edited volumes, book chapters, and his book The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History (1998). In all of his work, David acknowledged and even celebrated the complex relationship between historical objectivity and subjectivity.

Born in New York City in 1923, son of Max Lowenthal, lawyer, diplomat, confirmed New Dealer, and confidant of Presidents Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman, David witnessed the making and remaking of historical landscapes close up. After graduation from Harvard University in 1944, he enlisted in the US Army and was assigned to make a detailed survey of German castles—not for their historical or architectural significance but, rather, for their suitability for housing American occupation troops. This encounter with the changing spatial dimension of cultural behavior led him to a master’s degree in geography at the University of California Berkeley, where his lifelong interest in environmental studies and Caribbean societies arose. Yet David also had the soul of a reformer; his doctoral dissertation at the University of Wisconsin-Madison was on the pioneering work of George Perkins Marsh, a nineteenth-century American conservationist.

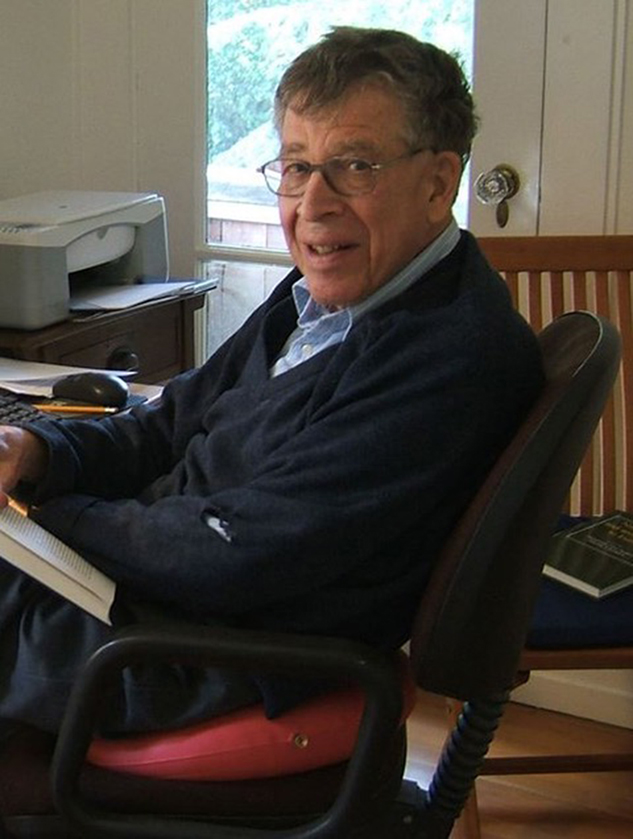

David’s academic career was long and varied. It took him from Madison, to Vassar, to the American Geographical Society (during which time, he had research stints at the University of the West Indies and the Institute of Race Relations in London); he subsequently joined the Faculty of University College London. His wife and partner Mary Alice Lowenthal, also a geographer by profession, became in later years David’s sounding board, editor, and overall enabler of his continuing research and travel. I remember so well the neat piles of edited and still-to-be-reviewed manuscript pages and newspaper and magazine clippings on the side tables in the living room of their apartment on Thayer Street in London; the odd and evocative stories about the clash of past and present contained in more than a few of those press clippings eventually found their way into a lecture or printed page.

David’s association with the International Society of Cultural Property was long and distinguished, serving as a founding member of the society’s board and on the editorial board of the International Journal of Cultural Property from its inaugural issue in 1992 to the time of his death. When John Henry Merryman established the society in 1990, the issues at stake were primarily legal and ethical, presuming that authenticity was a clear-cut matter for expert evaluation, and, once out of the way, led to questions about the rightful ownership of cultural property. But the precise definition of “authenticity” and clear criteria for what made certain property “cultural” were not quite as settled as they may have appeared. David’s article for the first volume of the society’s journal, “Counterfeit Art: Authentic Fakes?” characteristically tackled those basic concepts head on.

In his subsequent lectures and publications over decades, David more fully characterized the public fascination for “heritage” (and the cultural property that embodies it) as a cognitive activity rather than as a collection of specially designated places and things. He taught us that the past is indeed a foreign country, yet one that will forever remain mostly terra incognita, despite advances in historical and archaeological techniques. For David, history and heritage were the battlegrounds of a constant struggle between our urge to reshape the past in our own self-justifying image and the past’s enormous power to determine our inherited identities and attitudes about the world.

David could always be counted on to offer novel and insightful observations about the manipulation of the past for political or psychological reasons and the effects of that manipulation on the protection—even identification and claims to ownership—of tangible and intangible cultural property. Whether discussing the impact of theme parks on the design of visitor experiences at heritage sites, debating the character of historical objectivity versus heritage subjectivity, or weighing the pros and cons of repatriation claims, David Lowenthal was a unique and unforgettable figure in the field of heritage studies—a polymath and original thinker who left an indelible mark on the discipline.

At the time of his death on 15 September 2018, he was about to begin reviewing the proofs for his latest book, Quest for the Unity of Knowledge (published on schedule on 15 November), covering his wide range of his interests, including history, heritage, cultural property, environmental issues, and island cultures. David’s insatiable curiosity about the uses and misuses of heritage, his incisive analysis and critique of contemporary heritage practices and policies, his wit as a storyteller, and his unfailing kindness to students, colleagues, and friends will all be sorely missed.