No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

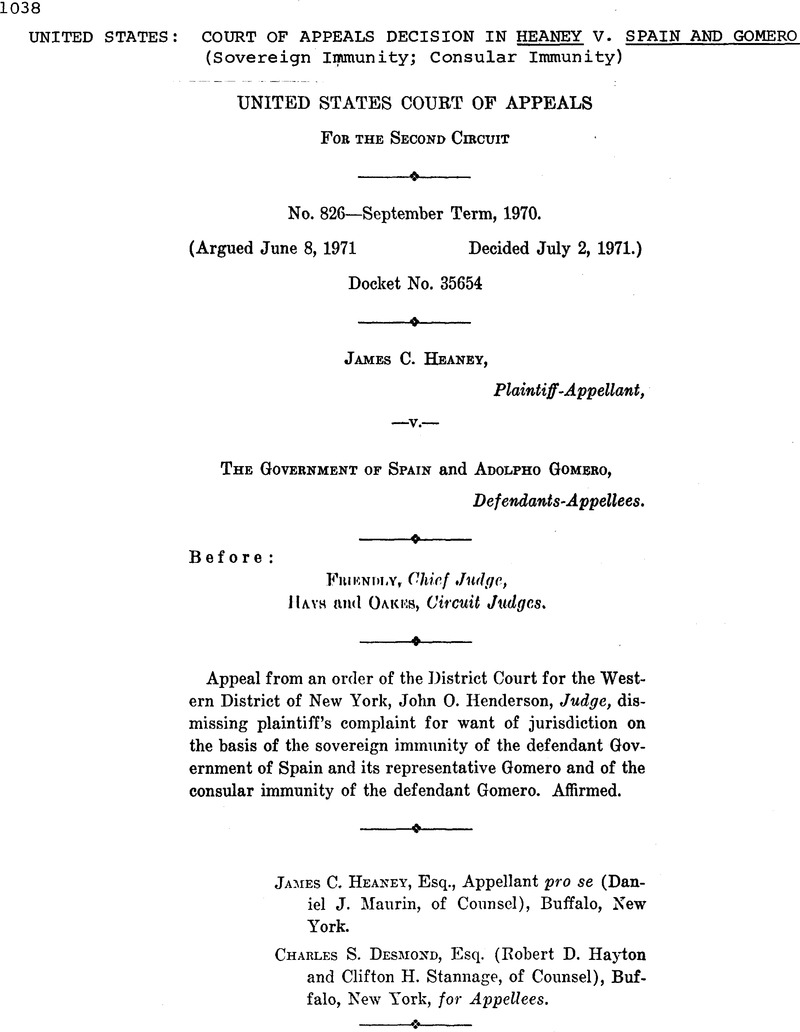

United States: Court of Appeals Decision in Heaney v. Spain and Gomero (Sovereign Immunity; Consular Immunity)

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1971

References

1 An affidavit in support of this motion submitted to the district court by His Excellency Jaime de Arguelles y Armada, the Spanish Ambassador to the United States, stated:

My Government has advised me that under international law and usage it cannot, with due regard to its national dignity, submit itself to the jurisdiction of the courts of a friendly, sovereign state. There-fore, I have been instructed, as Ambassador of my country, to make known to the Court that Spain most respectfully declines to waive its sovereign immunity or to consent to the jurisdiction of the Court.

The affidavit also stated, after noting that Gomero “has been and still is Consul General of Spain at New York”:

My Government has directed me to state that any conferences between Plaintiff and [Gomero] were held in his capacity as Consul General of Spain and on behalf of my Government as its representative. Therefore, I have been instructed by my Government to make known to the Court that Spain most respectfully declines to waive the immunity of its said representative ... or to consent to the jurisdiction of the Court over him.

2 In a letter dated May 24, 1971, we invited the State Department to submit its views on the questions presented by this case. The Department has not even acknowledged our letter.

3 The use of the term “diplomatic” in Victory Transport was obviously-intended in the broad sense of the word and was not meant to be limited to the activities of diplomatic missions.

4 Included in the concept of waiver is liability of a state initiating proceedings to a counterclaim of the opposing party. See National City Bank of New York v. Republic of China, supra, 348 U.S. 356, 364; ALI, Restatement of Foreign Relations Law of the United States $70 (1965).

5 The affidavit submitted to the district court by the Spanish Ambassador, see fn. 1 supra, with appropriate identifying documents, was more than sufficient to raise the issue of immunity by motion. Ex parte Muir, 254 U.S. 322, 532-33 (1921). While Heaney relies on the vagueness of his complaint in conjunction with the statement that a foreign government, in presenting a defense of immunity, must “prove most of the facts that underlie its claim,” ALI, Restatement of Foreign Relations Law of the United States $72 at 225 (comment) (1965), he ignores the next sentence of the Restatements comment which reads “Some of these facts, such as the existence of a foreign entity as a state and the status of its representative have already been conclusively determined by the acts of recognition and accreditation by the executive branch of the government of the United States.” Id. Heaney alleges no facts, as distinguished from legal conclusions, see, e.g., Pauling v. McElroy, 278 F.2d 252, 253-54 (D.C. Cir.), cert, denied, 364 U.S. 335 (1960); Gold V. Macy, 234 F. Supp. 764 (E.D.N.Y. 1964), which in light of the un-disputed status of the defendants and the principles discussed above, would defeat a claim of immunity.