Article contents

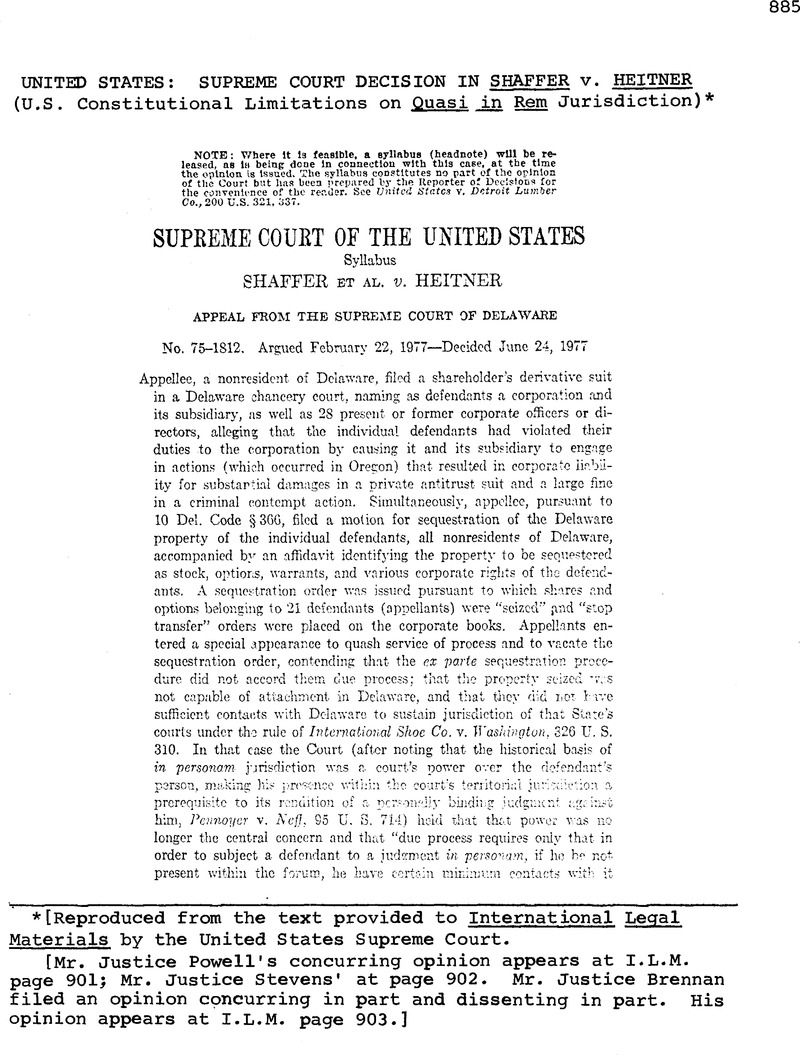

United States: Supreme Court Decision in Shaffer v. Heitner (U.S. Constitutional Limitations on Quasi in Rem Jurisdiction)*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 March 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1977

Footnotes

[Reproduced from the text provided to International Legal Materials by the United States Supreme Court.

[Mr. Justice Powell's concurring opinion appears at I.L.M. page 901; Mr. Justice Stevens’ at page 902. Mr. Justice Brennan filed an opinion concurring in part and dissenting in part. His opinion appears at I.L.M. page 903.]

References

1 Greyhound Lines, Inc., is incorporated in California and has its principal place of business in Phoenix, Ariz.

2 A judgment of 813,146,090 plus attorneys fees was entered against Greyhound in Mt. Hood Stages, Inc. v. Greyhound Corp., No. 68-374, D. Ore. (filed Nov. 29, 1973), aff’d, - F. 2d - (CA9, June 9, 1977). App. 10; see Mt. Hood Stages, Inc. v. Greyhound Corp., 1973-2 Trade Cas. ¶ 74,824.

3 See United States v. Greyhound Corp., 363 F. Supp. 525 (ND Ill. 1973), 370 F. Supp. 881 (ND 111.), aff’d, 508 F. 2d 529 (CA7 1974). Greyhound was fined $100,000 and Greyhound Lines .$500,000.

4 10 Del. C. § 366 provides:

“(a) If it appears in any complaint filed in the Court of Chancery that the defendant or any one or more of the defendants is a nonresident of the State, the Court may make an order directing such nonresident defendant or defendants to appear by a day certain to be designated. Such order shall be served on such nonresident defendant or defendants by mail or otherwise, if practicable, and shall be published in such manner as the Court directs, not less than once a week for 3 consecutive weeks. The Court may compel the appearance of the defendant by the seizure of all or any part of his property, which property may be sold under the order of the Court to pay the demand of the plaintiff, if the defendant does not appear, or otherwise defaults. Any defendant whose property shall have been so seized and who shall have entered a general appearance in the cause may, upon notice to the plaintiff, petition the Court for an order releasing such property or any part thereof from the seizure. The Court shall release such property unless the plaintiff shall satisfy the Court that because of other circumstances there is a reasonable possibility that such release may render it substantially less likely that plaintiff will obtain satisfaction of any judgment secured. If such petition shall not be granted, or if no such petition shall be filed, such property shall remain subject to seizure and may be sold to satisfy any judgment entered in the cause. The Court may at any time release such property or any part thereof upon the giving of sufficient security.

“(b) The Court may make all necessary rules respecting the form of process, the manner of issuance and return thereof, the release of such property from seizure and for the sale of the property so seized, and may require the plaintiff to give approved security to abide any order of the Court respecting the property.

“(c) Any transfer or assignment of the property so seized after the seizure thereof shall be void and after the sale of the property is made and confirmed, the purchaser shall be entitled to and have all the right, title and interest of the defendant in and to the property so seized and sold and such sale and confirmation shall transfer to the purchaser all the right, title and interest of the defendant in and to the property as fully as if the defendant had transferred the same to the purchaser in accordance with law."

5 As a condition of the sequestration order, both the plaintiff and the sequestrator wire required to file bonds of $1,000 to assure their compliance with the order.-: of the court. App. 24.

Following a technical amendment of the complaint, the original sequestration order was vacated and replaced by an alias sequestration order identical in its terms to the original.

6 The sequestrator is appointed by the court to effect the sequestration. His duties appear to consist of serving the sequestration order on the named corporation, receiving from that corporation a list of the property which the order affects, and filing that list with the court. For performing those services in this case, the sequestrator received a fee of $100 under the original sequent ration order and $100 under the alias order.

7 The closing price of Greyhound stock on the day the sequestration order was issued was $14⅜. New York Times, May 23, 1974, at 62. Thus, the value of the sequestered stock was approximately $1.2 million.

8 Debentures, warranty, and stock unit credits belonging to some of the defendants who owned either stock or options were also sequestered. In addition, Greyhound reported that it had an employment contract with one of the defendants calling for payment of $250,000 over a 12-month period. Greyhound refused to furnish any further information on that debt on the ground that since the sums due constituted wages, their seizure would be unconstitutional. See Sniadach v. Family Finance Corp., 395 U. S. 337 (1969). Heitner did not challenge this refusal.

The remaining defendants apparently owned no property subject to the sequestration order.

9 8 Del. C. § 169 provides:

“For all purposes of title, action, attachment, garnishment and jurisdiction of all courts held in this State, but not for the purpose of taxation, the situs of the ownership of the capital stock of all corporations existing under the laws of this State, whether organized under this chapter or otherwise, shall be regarded as in this State."

10 The court relied, 361 A. 2d, at 228, 230-231, on our decision in Ownbey v. Morgan, 250 U. S. 94 (1921), and references to that decision in North Georgia Finishing, Inc. v. Di-Chem, Inc., 419 U. S. 601, 610 (1975) (Powell, J., concurring); Calero-Toledo v. Pearson Yacht Leasing Co., 416 U. S. 603, 679 n. 14 (1974); Mitchell v. W. T. Grant Co., 416 U. S. 600, 013 (1974); Fuentes v. Shevin, 407 U. S. 67, 91 n. 23 (1972); Sniadach v. Family Finance Corp., 395 U. S. 337, 339 (1969). The only question before the Court in Ownbey was the constitutionality of a requirement that a defendant whose property has been attached file a bond before entering an appearance. We do not read the recent references to Ownbey as necessarily suggesting that Ownbey is consistent with more recent decisions interpreting the Due Process Clause.

Sequestration is the equity counterpart of the process of foreign attachment in suits at law considered in Ownbey. Delaware’s sequestration statute was modeled after its attachment statute. See Sands v. Lefcourt Realty Corp., 35 Del. Ch. 340, 344-345, 117 A. 2d 365, 367 (Sup. Ct. 1955); Folk & Moyer, Sequestration in Delaware: A Constitutional Analysis, 73 Colum. L. Rev. 749, 751-754 (1973).

11 The District Court judgment in U. S. Industries was reversed by the Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit. 540 F. 2d 142 (1976), petition for cert. pending, No. 76-359. The Court of Appeals characterized the passage from the Delaware Supreme Court’s opinion quoted in text as “cryptic conclusions.” Id., at 149.

12 Under Delaware law, defendants whose property has been requested must enter a general appearance, thus subjecting themselves to in personam liability, before they can defend on the merits. See Greyhound Corp. v. Heitner, supra, at 235-236. Thus, if the judgment below were considered not to be an appealable final judgment, 28 U. S. C. § 1257 (2), appellants would have the choice of suffering a default judgment or entering a general appearance and defending on the merits. This case is in the same posture as was Cox Broadcasting Corp. v. Cohn, 420 U. S. 469, 485 (1975): “The [Delaware] Supreme Court’s judgment is plainly final on the federal issue and is not subject to further review in the state courts. Appellants will be liable for damages if the elements of the state cause of action are proved. They may prevail at trial on nonfederal grounds, it is true, but if the [Delaware] court erroneously upheld the statute, there should be no trial at all."

Accordingly, “consistent with the pragmatic approach that we have followed in the past in determining finality,” id., at 486, we conclude that the judgment below is final within the meaning of § 1257.

13 The statute also required that a copy of the summons and complaint be mailed to the defendant if his place of residence was known to the plaintiff or could be determined with reasonable diligence. 95 U. S., at 718. Mitchell had averred that lie did not know and could not determine Neff’s address, so that the publication was the only “notice” given. 95 U. S., at 717.

14 The federal circuit court based its ruling on defects in Mitchell’s affidavit in support of the order for service by publication and in the affidavit by which publication was proved. Id., at 720. Justice Field indicated that if this Court had confined itself to considering those rulings, the judgment would have been reversed. Id., at 721.

15 The doctrine that one State does not have to recognize the judgment of another State’s courts if the latter did not have jurisdiction was firmly established at the time of Pennoyer. See, e. g., D’Arcy v. Ketchum, 11 How. 165 (1850); Boswell’s Lessee v. Otis, 9 How. 336 (1850); Kibbe v. Kibbe, Kirby 119 (Conn. Super. 1786).

16 Attachment was considered essential to the state court’s jurisdiction for two reasons. First, attachment combined with substituted service would provide greater assurance that the defendant would actually receive notice of the action than would publication alone. Second, since the court’s jurisdiction depended on the defendant’s ownership of property in the State and could be defeated if the defendant disposed of that property, attachment was necessary to assure that the court had jurisdiction when the proceedings began and continued to have jurisdiction when it entered judgment. 95 U. S., at 727-728.

17 “A judgment in rem affects the interests of all persons in designated property. A judgment quasi in rem affects the interests of particular persons in designated property. The latter is of two types. In one the plaintiff is seeking to secure a pre-existing claim in the subject property and to extinguish or establish the nonexistence of similar interests of particular persons. In the other the plaintiff seeks to apply what he concedes to be the property of the defendant to the satisfaction of a claim against him. Restatement, Judgments, 5-9.” Hanson v. Denckla, 357 U. S. 235, 246 n. 12.

As did the Court in Hanson, we will for convenience generally use the term “in rem” in place of “in rem and quasi in rem."

18 The Court in Harris limited its holding to States in which the principal defendant (Balk) could have sued the garnishee (Harris) if he had obtained personal jurisdiction over the garnishee in that State. 198 U. S. at 222-223, 226. The Court explained that

“[t]he importance of the fact of the right of the original creditor to sue his debtor in the foreign State, as affixing the right of the creditor of that creditor to sue the debtor or garnishee, lies in the nature of the attachment proceeding. The plaintiff, in such proceeding in the foreign State is able to sue out the attachment, and attach the debt due from the garnishee to his (the garnishee’s) creditor, because of the fact that the plaintiff is really in such proceeding a representative of the creditor of the garnishee, and therefore if such creditor himself had the right to commence suit to recover the debt in the foreign State his representative has the same right, as representing him, and may garnish or attach the debt, provided the municipal law of the State where the attachment was sued out permits it.” Id., at 226.

The problem with this reasoning is that unless the plaintiff has obtained a judgment establishing his claim against the principal defendant, see, e. g., Baltimore & O. R. Co. v. Hostctler, 2-40 U. S. 620 (1916), his right to “represent” the principal defendant in an action against the garnishee is at issue. See Scale, The Exercise of Jurisdiction in Rem to Compel Payment of a Debt, 27 Harv. L. Rev. 107, 118-120 (1913).

19 As the language quoted indicates, the International Shoe Court believed that the standard it was setting forth governed actions against natural persons as well as corporations, and we see no reason to disagree. See also McGee v. International Life Ins. Co., 355 U. S. 220, 222 (1957) (International Shoe culmination of trend toward expanding state jurisdiction over “foreign corporations and other nonresidents"). The differences between individuals and corporations may, of course, lead to the conclusion that a given set of circumstances establishes State jurisdiction over one type of defendant but not over the other.

20 Nothing in Hanson v. Denckla, supra, is to the contrary. The Hanson Court’s statement that restrictions on state jurisdiction “are a consequence of territorial limitations on the power of the respective States,” id., at 251, simply makes the point that the States are defined by their geographical territory. After making this point, the Court in Hanson determined that the defendant over which personal jurisdiction was claimed had not committed any acts sufficiently connected to the State to justify jurisdiction under the International Shoe standard.

21 Cf. Restatement (Second) of Conflict of Laws § 59 comment a (possible inconsistency between principle of reasonableness which underlies field of judicial jurisdiction and traditional rule of in rem jurisdiction based solely on land in State); § 60 comment a (same as to jurisdiction based solely on chattel in State); § 68 comment c (rule of Harris v. Balk “might be thought inconsistent with the basic principle of reasonableness").

22 “All proceedings, like all rights, are really against persons. Whether they are proceedings or rights in rem depends on the number of persons affected.” Tyler v. Court of Registration, 175 Mass. 71, 76, 55 N. E. 812, 814, appeal dismissed, 179 U. S. 405 (1900) (Holmes, C. J.).

23 It is true that the potential liability of a defendant in an in rem action is limited by the value of the property, but that limitation does not affect the argument. The fairness of subjecting a defendant to state court jurisdiction does not depend on the size of the claim being litigated. Cf. Fuentes v. Skevin, supra, at 88-90 (1972); n. 32, infra.

24 This category includes true in rem actions and the first type of quasi in rem proceedings. See n. 17, supra.

25 In some circumstances the presence of property in the forum State will not support the inference suggested in text. Cf., e. g., Restatement (Second) of Conflicts § 60, comments c, d; Traynor, supra, at 672-673 (1959); Note, The Power of a State to Affect Title in a Chattel A typically Removed to It, 47 Colum. L. Rev. 767 (1947).

26 Cf. Hanson v. Denchla, supra, at 253 (1957).

27 See, e.g., Tyler v. Court of Registration, supra, n. 22.

28 We do not suggest that these illustrations include all the factors that may affect the decision, nor that the factors we have mentioned are necessarily decisive.

29 Cf. Dubin v. City of Philadelphia, 34 Pa. D. & C. 61 (1938). If such an action were brought under the in rem jurisdiction rather than under a long arm statute, it would be a quasi in rem action of the second type. See n. 17, supra.

30 Cf. Smit, The Enduring Utility of In Rem Rules: A Lasting Legacy of Pennoyer v. Neff, 48 Brooklyn L. Rev. 600 (1977). We do not suggest that jurisdictional doctrines other than those discussed in text, such as the particularized rules governing adjudications of status, are inconsistent with the standard of fairness. See, e. g., Traynor, supra, at 660-661.

31 Concentrating on this category of cases is also appropriate because in the other categories, to the extent that presence of property in the State indicates the existence of sufficient contacts under International Shoe, there is no need to rely on the property as justifying jurisdiction regardless of the existence of those contacts.

32 The value of the property seized does serve to limit the extent of possible liability, but that limitation does not provide support for the assertion of jurisdiction. See n. 23, supra. In this case, appellants’ potential liability under the in rem jurisdiction exceeds one million dollars. See no. 7, 8, supra.

33 See pp. 5-6, supra. This purpose is emphasized by Delaware’s refusal to allow any defense on the merits unless the defendant enters a general appearance, thus submitting to full in personam liability. See n. 12, supra.

34 See North Georgia Finishing, Inc. v. Di-Chem, Inc., supra; Mitchell v. W. T. Grant Co., supra; Fuentes v. Shevin, supra; Sniadach v. Family Finance Corp., supra.

35 The role of in rem jurisdiction as a means of preventing the evasion of obligations, like the usefulness of that jurisdiction to mitigate the limitations Pennoyer placed on in personam jurisdiction, may once have been more significant. Von Mehren & Trautman, supra, at 1178.

36 Once it has been determined by a court of competent jurisdiction that the defendant is a debtor of the plaintiff, there would seem to be no unfairness in allowing an action to realize on that debt in a State where the defendant has property, whether or not that State would have jurisdiction to determine the existence of the debt as an original matter. Cf. n. 18, supra.

37 This case does not raise, and we therefore do not consider, the question whether the presence of a defendant’s property in a State is a sufficient basis for jurisdiction when no other forum is available to the plaintiff.

38 To the contrary, in Pennington v. Fourth National Bank, 243 U. S. 269,271 (1917), we said:

“The Fourteenth Amendment did not, in guaranteeing due process of law, abridge the jurisdiction which a State possessed over property within its borders, regardless of the residence or presence of the owner. That jurisdiction extends alike to tangible and to intangible property. Indebtedness due from a resident to a non-resident—of which bank deposits are an example—is property within the State. Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Ry. Co. v. Sturm, 174 U. S. 710. It is, indeed, the species of property which courts of the several States have most frequently applied in satisfaction of the obligations of absent debtors. Harris v. Balk, 198 U. S. 215, Substituted service on a non-resident by publication furnishes no legal basis for a judgment in personam. Pennoyer v. Neff, 95 U. S. 714. But garnishment or foreign attachment is a proceeding quasi in rem. Freeman v. Alderson, 119 U, S, 185. 187. The thing belonging to the absent defendant is seized and applied to the satisfaction of his obligation. The Federal Constitution presents no obstacle to the full exercise of this power."

See also Huron Holding Corp. v. Lincoln Mine Operating Co., 312 U. S. 183, 193. (1941).

More recent decisions, however, contain no similar sweeping endorsements of jurisdiction based on property. In Hanson v. Denckla, supra, at 246, we noted that a State court’s in rem jurisdiction is “[f]ounded on physical power” and that “[t]he basis of the jurisdiction is the presence of the subject property within the territorial jurisdiction of the forum State.” We found in that case, however, that the property which was the basis for the assertion of in rem jurisdiction was not present in the State. We therefore did not have to consider whether the presence of property in the State was sufficient to justify jurisdiction. We also held that the defendant did not have sufficient contact with the State to justify in personam jurisdiction.

39 It would not be fruitful for us to re-examine the facts of cases decided on the rationales of Pennoyer and Harris to determine whether jurisdiction might have been sustained under the standard we adopt today. To the extent that prior decisions are inconsistent with this standard, they are overruled.

40 Appellants argue that our determination that the minimum contacts standard of International Shoe governs jurisdiction here makes unnecessary any consideration of the existence of such contacts. Brief, at 27; Reply Brief, at 9. They point out that they were never personally served with a summons, that Delaware has no long arm statute which would authorize such service, and that the Delaware Supreme Court has authoritatively held that the existence of contacts is irrelevant to jurisdiction under 10 Del. C. § 366. As part of its sequestration order, however, the Court of Chancery directed its clerk to send each appellant a copy of the summons and complaint by certified mail. The record indicates that those mailings were made and contains return receipts from at least 19 of the appellants. None of the appellants has suggested that he did not actually receive the summons which was directed to him in compliance with a Delaware statute designed to provide jurisdiction over nonresidents. In these circumstances, we will assume that the procedures followed would be sufficient to bring appellants before the Delaware courts, if minimum contacts existed.

41 On the view we take of the case, we need not consider the significance, if any, of the fact that some appellants hold positions only with a subsidiary of Greyhound which is incorporated in California.

42 Sequestration is an equitable procedure available only in equity actions;, but a similar procedure may be utilized in actions at law. See n. 10, supra.

43 Delware does not require directors to own stock. 8 Del. C. § 141 (b).

44 In general, the law of the State of incorporation is held to govern the liabilities of officers or directors to the corporation and its stockholders. See Restatement (Second) of Conflict of Laws § 309. But see Cal. Corp. Code § 2115 (West Supp. 1976). The rationale for the general rule appears to be based more on the need for a uniform and certain standard to govern the internal affairs of a corporation than on the perceived interest of the state of incorporation. Cf. Koster v. Lumbermens Mutual Casualty Co., 330 U. S. 518, 527-528 (1947).

45 Justice Black, although dissenting in Hanson, agreed with the majority that “the question whether the law of a State can be applied to a transaction is different from the question whether the courts of that State have jurisdiction to enter a judgment . . . .” 357 U. S., at 258.

46 See, e. g., 8 Del. C. §§ 143, 145.

47 See, e. g., Conn. Gen. Stat. §33-322; N. C. Gen. Stat. §55-33; S. C.

1 Indeed, the Court’s decision to proceed to the minimum contacts issue treats Delaware’s sequestration statute as if it were the equivalent of Rhode Island’s long-arm law, which specifically authorizes its courts to assume jurisdiction to the limit permitted by the Constitution, R. I. Gen. Laws Ann. 9-5-33, thereby necessitating judicial consideration of the frontiers of minimum contacts in every case arising under that statute.

2 The Mullane Court held: “[T]he interest of each state in providing means to close trusts that exist by the grace of its laws and are administered under the supervision of its courts is so insistent and rooted in custom as to establish beyond doubt the right of its courts to determine the interests of all claimants, resident or nonresident, provided its procedure accords full opportunity to appear and be heard."

3 In this case the record does not inform us whether an actual conflict is likely to arise between Delaware law and that of the likely alternative forum. Pursuant to the general rule, I assume that Delaware law probably would obtain in the foreign court. Restatement (Second) Conflicts of Law § 309.

4 I recognize, of course, that identifying a corporation as a resident of the chartering state is to build upon a legal fiction. In many respects, however, the law acts as if state chartering of a corporation has meaning. E. g., 28 U. S. C. § 1332 (c) (for diversity purposes, a corporation is a citizen of the state of incorporation). And, if anything, the propriety of treating a corporation as a resident of the incorporating state seems to me particularly appropriate in the context of a shareholder derivative suit, for the state realistically may perceive itself as having a direct interest in guaranteeing the enforcement of its corporate laws, in assuring the solvency and fair management of its domestic corporations, and in protecting from fraud those shareholders who placed their faith in that state-created institution.

5 In fact, it is quite plausible that the Delaware Legislature never felt the need to assert direct jurisdiction over corporate managers precisely because the sequestration statute heretofore has served as a somewhat awkward but effective basis for achieving such personal jurisdiction. See, e. g., Hughes Tool Co. v. Fawcett Publications, Inc., 290 A. 2d 693, 695 (Del. Ch. 1972): “Sequestration is most frequently resorted to in suits by stockholders against corporate directors in which recoveries are sought for the benefit of the corporation on the ground of claimed breaches of fiduciary duty on the part of directors."

6 Admittedly, when one consents to suit in a forum, his expectation is enhanced that he may be haled into that State’s courts. To this extent, I agree that consent may have bearing on the fairness of accepting jurisdiction. But whatever is the degree of personal expectation that is necessary to warrant jurisdiction should not depend on the formality of establishing a consent law. Indeed, if one’s expectations are to carry such weight, then appellant here might be fairly charged with the understanding that Delaware would decide to protect its substantial interests through its own courts, for they certainly realized that in the past the sequestration law has been employed primarily as a means of securing the appearance of corporate officials in the State’s courts. Supra, at n. 5. Even in the absence of such a statute, however, the close and special association between a state corporation and its managers should apprise the latter that the state may seek to offer a convenient forum for addressing claims of fiduciary breach of trust.

7 Whether the directors of the out-of-state subsidiary should be amenable to suit in Delaware may raise additional questions. It may well require further investigation into such factors as the degree of independence in the operations of the two corporations, the interrelationship of the managers of parent and subsidiary in the actual conduct under challenge, and the reasonable expectations of the subsidiary directors that the parent state would take an interest in their behavior. Cf. United States v. First National City Bank, 379 U. S. 378, 3S4 (1965). While the present record is not illuminating on these matters, it appears that all appellants acted largely in concert with respect to the alleged fiducial misconduct, suggesting that overall jurisdiction might fairly rest in Delaware.

8 And, of course, if a preferable forum exists elsewhere, a State that is constitutionally entitled to accept jurisdiction nonetheless remains free to arrange for the transfer of the litigation under the doctrine of forum, non convenient. See, e. g., Broderick v. Rosner, 274 U. S. 629, 643 (1935); Gulf Oil Co. v. Gilbert, supra, at 504.

- 6

- Cited by