No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

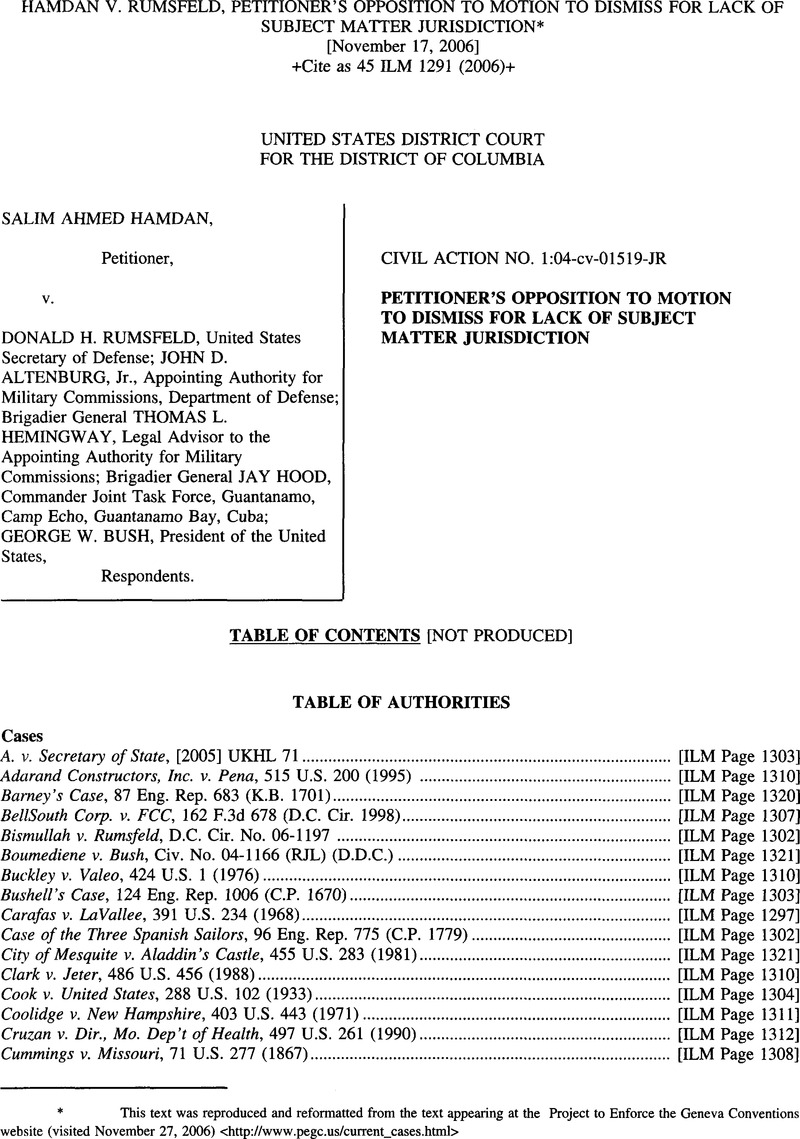

This text was reproduced and reformatted from the text appearing at the Project to Enforce the Geneva Conventions website (visited November 27, 2006) <http://www.pegc.us/current_cases.html>

1 Indeed, under the Government's reading of the MCA, this Court would be powerless to prevent Mr. Hamdan from being tried under the President's November 13, 2001 Military Order despite the fact that the Supreme Court has explicitly barred it. At best, his only legal right would occur years down the road, once the government decided to take the steps of a) charging him; b) trying him; and c) rendering a final judgment approved by the convening authority and even then it would only be the most truncated form of review.

2 Scaggs v. Larsen, 396 U.S. 1206, 1208 (1969) (Douglas, J.) (“[Section] 2241 is not a measure of the constitutional scope of the guarantee [of habeas]….”).

3 The Rasul Court supported this conclusion by citing to Justice Kennedy's concurrence in United States v. Verdugo-Urquidez, 494 U.S. 259, 277-78 (1990) (Kennedy, J., concurring) and the cases cited in that concurrence. All of those cases addressed claims under the Constitution, not statutes or treaties. Indeed, Justice Kennedy's opinion emphasized that Verdugo-Urquidez did not repudiate the long-established principle that“the Government may act only as the Constitution authorizes, whether the actions in question are foreign or domestic … The question before us then becomes what constitutional standards apply when the Government acts, in reference to an alien, within its sphere of foreign operations.” Verdugo-Urquidez, Id. at 277 (Kennedy, J., concurring). See also Amicus Br. of Former Federal Judges, Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, No. 05-184 (2006), at 2-9 (discussing Rasul and Verdugo-Urquidez)

4 Another negative inference may be drawn from the express reference to habeas actions in MCA § 950j, which expresslymentions habeas in the course of divesting courts of jurisdiction over actions “relating to the prosecution, trial, or judgment of a military commission under this chapter.” To be sure, the combined effect of MCA § 7(a)(2) and 7(b) is to bar some challenges to military commissions, such as those day-to-day ones that are best handled after the trial is completed. But 7(b) does not bar a habeas challenge to a military commission in a pending case, it only attempts to extend its prohibition retroactively to the § 7(a)(2) provision by its very terms. And it is quite clear that a challenge to the legality of the military commission itself is not a challenge “relatfing] to any aspect of the … trial.” MCA 7(b). Such challenges do not go to procedural rulings by the commission, they challenge the commission itself. They relate not to an “aspect” of them, but to their entirety. For similar reasons, Section 3(a), which attempts to bar jurisdiction of claims “relating to the prosecution, trial, or judgment of a military commission under this chapter” does not bar this Court's jurisdiction to consider structural legal challenges to military commissions. As its title makes clear, this section means that the “Provisions of [the] Chapter [are the] Sole Basis for Review of Military Commission Procedures and Actions.” That language might, absent Suspension Clause problems, bar day-to-day challenges to particular decisions made by a military commission, but does not bar challenges to the military commission itself. Finally, even if MCA § 950j does not suspend the writ, Petitioner's habeas action also includes a separate challenge to his detention as an enemy combatant, which is not affected by MCA § 950j. Additional support for this reading is found in Hamdan itself, where the Supreme Court held that DTA §§ 1005(e) and (h) did not strip the federal courts of jurisdiction to hear Hamdan's challenge to the validity of the military commissions. The Court found that the DTA distinguished between, on the one hand, pending cases that challenged the validity of the military commissions and, on the other hand, “more routine” challenges to the final orders of commissions and combatant status review tribunals. Id. at 2769. The DTA, said the Court, only stripped the lower courts of jurisdiction to hear the latter type of cases. Id. In finding that the DTA created this “hybrid” system for reviewing different types of challenges to the military commissions, the Court stated that Congress may have had “good reason” to preserve jurisdiction for those cases that “challenge the very legitimacy of the tribunals whose judgments Congress would like to have reviewed,” while “channeling] to a particular court and through a particular lens of review” those “more routine challenges to final decisions rendered by those tribunals.” Id.; see also id. at 2768-69 (“[S]Jubsections (e)(2) and (e)(3) [of the DTA] grant jurisdiction only over actions to ‘determine the validity of any final decision’ of a CSRT or commission. Because Hamdan, at least, is not contesting any ‘final decision’ of a CSRT or military commission [but rather is contesting the very legitimacy of the commissions], his action does not fall within the scope of subsection (e)(2) or (e)(3).”). This distinction applies equally to the hybrid system of review devised by Congress in the MCA. This Court recognized that Hamdan was challenging not only the procedures that would be used to try him, but also the very jurisdiction of the commission itself. Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, 344 F. Supp. 2d. 152,157 (D.D.C. 2004). The Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit corroborated this reasoning, noting that under its precedents ‘“a person need not exhaust remedies in a military tribunal if the military court has no jurisdiction over him,'” Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, 415 F.3d 33, 36 (D.C. Cir. 2005) (quoting New v. Cohen, 129 F.3d 639, 644 (D.C. Cir. 1997), and that jurisdictional challenges to the military commissions must therefore be allowed to proceed so long as they are “not insubstantial,” id. at 37. The Supreme Court likewise held that abstention was inappropriate in Ham-dan's case. 126 S. Ct. at 2772 (quoting Exparte Quirin, 317 U.S. 1,19 (1942)).’ ‘Hamdan and the Government,'’ the Court observed, “both have a compelling interest in knowing in advance whether Hamdan may be tried by a military commission that arguably is without any basis in law and operates free from many of the procedural rules prescribed by Congress for courts-martial.” Id. at 2772. In each of these instances, the courts refused to apply Councilman abstention because they recognized that challenges to the very legitimacy of a military commission are qualitatively different from challenges to particular aspects of a commission. The DTA respected this distinction by refraining from stripping jurisdic-tion over pending habeas cases—cases which, by definition, would challenge the validity of the military commissions. The MCA has now done the same. In both statutes, Congress, like the courts, made allowance for the fact that certain fundamental claims must be allowed to proceed so as to assure the constitutionality of the very scheme Congress has authorized. This reading does not render the MCA redundant of the DTA. The significance of Section 7 of the MCA is not that it strips habeas jurisdiction in pending cases, but that it expands the territorial reach of the withdrawal of habeas jurisdiction to detainees held anywhere in the world instead of simply to Guantanamo.

5 Indeed, in St. Cyr, the Court held that a statutory provision entitled “Elimination of Custody Review by Habeas Corpus” did not repeal habeas jurisdiction because the operative text of the statute did not specifically mention habeas corpus, 533 U.S. at 308-10, just as Section 7(b) of the MCA does not mention habeas corpus. “Elimination of Custody Review by Habeas Corpus” is certainly a much more suggestive title than MCA § 7's title of “Habeas Corpus Matters” with regard to jurisdiction-stripping, which implies that the MCA is even more deficient in meeting the clear statement requirement than the statute at issue in St. Cyr.

6 In Felker, the Court assumed, for purposes of that decision, that “the Suspension Clause of the Constitution refers to the writ as it exists today, rather than as it existed in 1789.” Felker, 518 U.S. at 663-64.

7 For further discussion of the speedy inquiry afforded by habeas, see Amicus Br. of Commonwealth Lawyers Ass'n., Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, No. 05-184 (2006) at 6-8 & n.9 (collecting cases).

8 See discussion of the case in R.J. Sharpe, The Law of Habeas Corpus 66 n.15 (2d ed. 1989); see also Good's Case, 96 Eng. Rep. 137 (K.B. 1760) (releasing petitioner after examining affidavit showing that as a ship's carpenter he was exempt from impressment); Rex v. Greenwood, 93 Eng. Rep. 1086 (K.B. 1739) (considering affidavits of eight “credible persons ”introduced after indictment but prior to trial of accused robber); Barney's Case, 87 Eng. Rep. 683 (K.B. 1701) (bailing accused murderer after considering affidavits showing that it was a malicious prosecution).

9 For example, in United States v. Johns, 4 Dall. 412, 413 (Cir. Ct. 1806), the court heard oral testimony to evaluate a habeas petition alleging unlawful pre-trial detention. In Exparte Bennett, 3 F.Cas. 204 (C.C.D.D.C. 1825) (No. 1,311), the court at the habeas hearing re-examined a witness who had previously appeared before the committing magistrate; see also State v. Joseph Clark, 2 Del. Cas. 578 (Del. Chancery 1820) (releasing habeas petitioner from military enlistment after reviewing his affidavit traversing the return, and hearing live testimony from his father).

10 Already by 1670 habeas corpus was recognized as “the most usual remedy by which a man is restored again to his liberty, if he have been against law deprived of it.” 124 Eng. Rep. at 1007 (Vaughan, C.J.).

11 The Supreme Court's decision in McNary v. Haitian Refugee Center, Inc., 498 U.S. 479 (1991), is instructive on this point. While not a habeas action, that case did involve jurisdiction-stripping provisions of a federal statute in the context of a constitutional challenge to an administrative status determination involving aliens. The Court affirmed the decision of the court of appeals that the jurisdiction-stripping provisions of the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (“Reform Act”) would not prevent federal courts from considering the plaintiffs’ challenge. The judicial review provided under the Reform Act was limited to review after an administrative status determination had occurred, but only if it resulted in an order of exclusion or deportation. Id. at 486 n.6. In addition, the scope of the review was to “be based solely upon the administrative record” under an “abuse of discretion” standard. Id. The Court allowed the plaintiffs’ challenges to pro-ceed despite the jurisdiction-stripping language of the Reform Act, in part because “the [administrative] procedures [did] not allow applicants to assemble adequate records,” and the courts, if and when they did obtain jurisdiction under the Reform Act, would “have no complete or meaningful basis upon which to review application determinations.” Id. at 496. In addition, the Court took exception to the fact that under the Reform Act, judicial review would only be available if deportation procedures were initiated because as a practicalmatter, that could be “tantamount to a complete denial of judicial review.” Id. at 496-97.

12 This Court found that CSRT procedures allowed for reliance on statements obtained through coercion or torture. See In re Guantanamo Detainees, 355 F. Supp. 2d at 472. See also 11/ 1/06 Amicus Brief of Retired Federal Jurists in Al Odah v. Bush, D.C. Cir. Case No. 05-5064 at 5-10.

13 See, e.g., Jackson v. Denno, 378 U.S. 368, 385-86 (1964).

14 Transcript of 12/2/04 oral argument at 83-87, Boumediene v. Bush, Civ. No. 04-1166 (RJL) (D.D.C.). Swift Decl. 1 33, Ex. 8.

15 While the DTA required the Department of Defense to revise its procedures so that future CSRTs would, “to the extent practicable, assess whether any statement derived from or relating to such detainee was obtained as a result of coercion; and the probative value (if any) of any such statement,” DTA § 1005(b), the MCA explicitly states that the determination of enemy combatant status by CSRTs pre-dating the DTA is final, at least for purposes of eligibility for trial by a military commission. MCA § 948a(l)(ii).

16 Duker notes that enforcement of treaty rights via habeas was regarded by the Supreme Court as a “special circumstance” requiring immediate federal intervention, one which justified waiving exhaustion of remedies requirements that were begin ning to emerge in 19th century jurisprudence. Duker, op.cit. at 200.

17 See Government's Supplemental Brief Addressing the Mili tary Commissions Act, in Boumediene et al. v. Bush and AlOdah et al. v. United States, Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, Nos. 05-5062, 05-5063-64, 05-095 through 05-5116 (November 13, 2006) at 12-16, 23.

18 Despite Hamdan's detention for more than five years, no court has passed on the question of whether “active hostilities” with al Qaeda are currently under way, which is the fundamental predicate of any war-time detention and, per Eisentrager, within the scope of a habeas inquiry. Hamdi, 542 U.S. at 520 (“It is a clearly established principle of the law of war that detention may last no longer than active hostilities.”).

19 Dismissal now and post-trial review later is particularly inade-quate in Mr. Hamdan's case, because Hamdan must preserve his ability to enforce this Court's November 8 Order as affirmed by the Supreme Court. The fact that the government has not yet charged Mr. Hamdan does not weigh against the exercise of continuing jurisdiction, as controversy over the jurisdiction and legality of the military commission presently exists in this case. The Supreme Court has repeatedly warned that other jurisdictional doctrines, such as mootness, do not permit a party to benefit from delaying challenged conduct. A “defendant's voluntary cessation of a challenged practice does not deprive a federal court of its power to determine the legality of the practice.” City ofMesquite v. Aladdin's Castle, 455 U.S. 283, 289 (1981). Otherwise, a defendant would be “free to return to his old ways.” United States v. W.T. Grant, 345 U.S. 629, 632 (1953). A key rationale for the voluntary cessation doctrine is to avoid procedural manipulations to deprive a court of jurisdiction. For that reason, a case will be dismissed only “if subsequent events make it absolutely clear that the allegedly wrongful behavior could not reasonably be expected to recur.” United States v. Concentrated Phosphate Export Assn., 393 U.S. 199, 203 (1968). As Justice Scalia has warned, courts should be “skeptical” that “cessation of violation means cessation of live controversy.” Friends of the Earth, Inc. v. Laidlaw Environmental Services (TOC), Inc., 528 U.S. 167, 214 (2000) (Scalia, J., dissenting). See also Erie v. Pap's A.M., 529 U.S. 277, 287-88 (2000).

20 Likewise, in Hicks v. Bush, 397 F. Supp. 2d 36 (D.D.C. 2005), this Court issued an injunction halting a military commission in order “to maintain its jurisdiction over Petitioner's claim that a military commission lacks jurisdiction to try him, a claim which Petitioner is entitled to have adjudicated by this Court prior to trial before a military commission.” Id. at 41 (emphasis added). In Hicks, this Court noted both “the established right to pre-commission review of jurisdictional issues,” and the irreparable injury that would result from being “tried by a tribunal without authority to adjudicate the charges against him in the first place, potentially subjecting him to a second trial before a second tribunal.” Id. at 41-42.

21 The MCA attempts to codify the Executive's ability to conduct interminable trials (or to conduct none at all) by removing from commissions speedy trial rights provided under the UCMJ. See MCA§ 948b(d)(A) (identifying 10 U.S.C. § 810 “relating to speedy trial, including any rule of courts-martial relating to speedy trial” as a provision of the UCMJ that “shall not apply to trial by military commission under [the MCA]”).

22 It should also be noted that the definition of “unlawful enemy combatant” in the MCA includes “a person who is part of the Taliban, al Qaeda, or associated forces.” MCA § 948a(l)(A)(i). The Taliban were the armed forces of a sovereign state, Afghanistan, when American military personnel invaded that country in the fall of 2001. This is a legislative decree that strips members of that military force of protections and immunities that, at the very least, may be afforded to them under the laws of war. As such, it is a Bill of Attainder. By stripping the courts of jurisdiction over habeas claims filed by members of the Taliban “or associated forces” held at Guantanamo, the MCA “prescribed] a rule for the decision of a cause in a particular way” every bit as much as the jurisdictional strip in Klein. It is an unconstitutional “means to an end” because the Taliban and “associated forces” are defined as unlawful combatants, i.e., as criminals, and the courts are directed that that determination is “dispositive.” MCA § 948d(c), § 948a(l)(A)(ii). Indeed, even if there were a subsequent judicial review under MCA § 7 (and there is no assurance that there would be, as that section purports to strip habeas jurisdiction for anyone “awaiting” an enemy combatant status determination), MCA § 5 provides that Ge neva Convention rights-concerning combatant immunity as a POW, for example - cannot be invoked. This is directly analogous to the situation in Klein, where, for example, “the court [was] forbidden to give the effect to evidence which, in its own judgment, such evidence should have.” Klein, 80 U.S. at 147.

23 Although, for reasons discussed below, Hamdan is protected by the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment, his invoca tion of rights under the Attainder Clause is not dependent on that fact. Structural limits on Congress' power-like the Attainder Clause-are exempt from any analysis as to whether the claimant may have individual constitutional rights. To sustain the judgment in the case under consideration, it by no means becomes necessary to show that none of the articles of the Constitution apply to the island of Porto Rico. There is a clear distinction between such prohibitions as go to the very root of power of Congress to act at all, irrespective of time or place, and such as are operative only “throughout the United States” or among the several states. Thus, when the Constitution declares that “no bill of attainder or ex post facto law shall be passed” and that “no title of nobility shall be granted by the United States,” it goes to the competency of Congress to pass a bill of that description. Downes v. Bidwell, 182 U.S. 244, 276-77 (1901) (emphasis in original).

24 Cummings stated that the “deprivation of any rights, civil or political, previously enjoyed may be punishment, the circum stances attending and the causes of the deprivation determining this fact.” 71 U.S. at 320. The Court specifically provided that “[disqualification … from the privilege of appearing in the courts, or acting as an executor, administrator, or guard ian, may also, and often has been, imposed as punishment.” Id.

25 This includes challenging whether the crime with which he is charged constitutes a valid war crime and thus falls within the MCA's valid jurisdiction. Hamdan, 126 S.Ct. at 2780-81. If and when the Government does charge him, the MCA would prevent that challenge if its jurisdiction stripping provisions are given full effect.

26 The taking away of “any rights, civil or political, previously enjoyed” also evinces an intent to punish. Cummings, 71 U.S. at 320. There is no doubt that, before the MCA's passage, Hamdan was entitled to bring a habeas claim challenging his detention, as well as a pre-trial claim challenging the commission. Rasul, 542 U.S. at 484-85 (habeas rights permit ting detention challenges extend to those detained at Guanta- namo); Hamdan, 126 S.Ct. at 2767-68 (discussing ability to challenge commission itself).

27 The length of Mr. Hamdan's detention - now five years and running - itself suggests that the nonpunitive aspects of his detention have been overwhelmed by the punitive ones. See United States v. Melendez-Carrion, 820 F.2d 56 (2d Cir. 1987) (looking in part to length of detention to decide whether it is punishment); United States v. Ojeda-Rios, 846 F.2d 167 (2d Cir. 1988) (finding 32 month detention unconstitutional).

28 The Government has recently confirmed that it will enforce the MCA against resident aliens who are both arrested and jailed in the United States. See Swift Decl. f 34, Ex. 9 (Respon dent-Appellee's Motion to Dismiss for Lack of Jurisdiction and Proposed Briefing Schedule, Al-Marri v. Wright, No. 06-7427 (4th Cir., November 13, 2006)). In Al-Marri, the Government has sought dismissal of the petitioner's habeas action on the basis of the MCA's jurisdiction-stripping provi sions and its determination that the petitioner is an “enemy combatant.” Id. at 2-5. Al-Marri is a lawful resident alien who was arrested at his home in Peoria, IIIinois and is currently imprisoned at the Navy Brig in Hanahan, South Carolina; he maintains that he is not an enemy combatant. Swift Decl. f 35, Ex. 10 (Petitioner-Appellant's Merits Brief, Al-Marri v. Wright, No. 06-7427 (4th Cir., November 13, 2006)) at 3-4.

29 Although the petitioners in Griffin and Douglas happened to be indigent, the Court has subsequently held that poverty is not a suspect class. Harris v. McRae, 448 U.S. 297 (1980). This clarified that the basis for the Court's equal protection decision in Griffin and Douglas rests on the deprivation of access to the courts, not the specific petitioner's economic circumstances.

30 In addition, the Suspension Clause places an important struc tural limitation on the powers of Congress, and preserves for the Judiciary an essential role in safeguarding liberty. This is wholly independent of the issue of whether aliens do, or do not, possess constitutional rights. Hamdi, 542 U.S. at 536 (“Whatever power the United States Constitution envisions for the Executive in its exchanges with other nations or with enemy organizations in times of conflict, it most assuredly envisions a role for all three branches when individual liberties are at stake.”)