No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

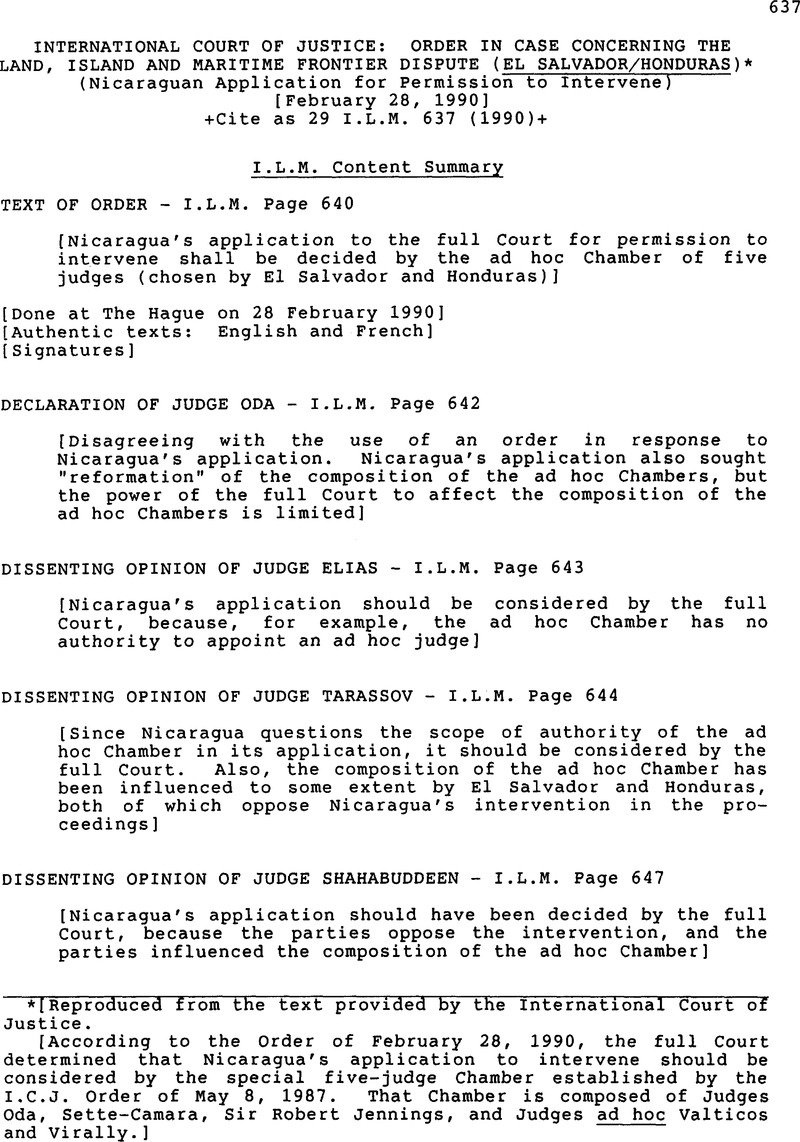

* [Reproduced from the text provided by the International Court of Justice.[According to the Order of February 28, 1990, the full Court determined that Nicaragua's application to intervene should be considered by the special five-judge Chamber established by the I.C.J. Order of May 8, 1987. That Chamber is composed of Judges Oda, Sette-Camara, Sir Robert Jennings, and Judges ad hoc Valticos and Virally.]

1 This lacuna in the guiding documents of the Court is quite understandable, however, as the Statute of the Court and the Rules of Court (even the most recent 1978 version) were elaborated and adopted at a time when adhoc chambers for the most part did not exist. It is well known that, if procedural rules are to be both sound and helpful, they must be developed on the basis of prolonged practical experience and embody the sum total of such experience. The theoretical elaboration of the present rules in this field was mainly based on the good intention of making it easier for States to attain a peaceful settlement of their disputes while enhancing the activity of the International Court of Justice. It is significant that it is precisely the practical experience of recent chamber cases that has aroused interest in this useful and promising institution among the judges of the International Court of Justice (see dissenting opinion of Judge Shahabuddeen to this Order, p. 21, infra, footnote).

1 The issue has been the subject of individual statements, made mostly out of Court, by a number of past and present Members of the Court, and from these I have benefited greatly and gratefully. See Judges Oda, Morozov and El Khani in the case concerning Delimitation of the Maritime Boundary in the Gulf of Maine Aera, I.C.J. Reports 1982, pp. 10,11 and 13 respectively; Eduardo Jiménez de Aréchaga, “The Amendments to the Rules of Procedure of the International Court of Justice”, American Journal of International Law, 1973, Vol. 67, p. 1; B. A. S.Petrén, “Some Thoughts on the Future of the International Court of Justice”, Netherlands Yearbook of International Law, 1975, Vol. 6, p. 59; Mohammed Bedjaoui, “Remarques sur la création de chambres adhoc an sein de la Cour Internationale de Justice”, Société francaise pour le droit international, Col-loque de Lyon, Lajuridiction Internationalepermanente, Paris, Pedone, 1987, pp. 73-78; Mohammed Bedjaoui, “Universalisme et régionalisme au sein de la Cour internationale de Justice: La constitution de chambres adhoc ', Liber Amicorum, Colección de Estudios Juridicos en Homenaje al Prof. Dr. D. José Pérez Montero, Universidad de Oviedo, 1988, p. 155; Stephen M. Schwebel, “AdHoc Chambers of the International Court of Justice”, American Journal of International Law, 1987, Vol. 81, p. 831; Stephen M. Schwebel, “Chambers of the International Court of Justice Formed for Particular Cases”, in Y. Dinstein (ed.), International Law at a Time of Perplexity, 1989, p. 739; Shigeru Oda, “Further Thoughts on the Chambers Procedure of the International Court of Justice”, American Journal of International Law, 1988, Vol. 82, p. 556; T.O. Elias, The United Nations Charter and the World Court, Lagos, 1989, pp. 16 and 203 ff.; and Hermann Mosler, “The Adhoc Chambers of the International Court of Justice: Evaluation after Five Years of Experience”, in Dinstein, op. cit., p. 449.

1 For the general theorv underlying an electoral secrecy provision, see the Maple Valley Case(]926) 1 D.L.R. 808, at pp. 814-815; 29 Corpus Juris Secundum, para. 201 (1), pp. 557-558; and Withers v. Board of Commissioners of Harnett County (1929) 146 S.E.

1 Consider, for example, the general understanding reflected in the statements made by M. Raested, in League of Nations, Committee of Jurists on the Statute of the Permanent Court of International Justice, Minutes of the Session Held at Geneva, March 11th- 19th, 1929, p. 42. And see R. v. Craske, ex parte Metropolitan Police Commissioner [1957] 2 Q.B. 591, and Sookoov. Attorney General of Trinidad and Tobago(1985) 33 W.I.R. 338, at p. 360 j , and, on appeal, [1986] 1 A.C. 63, P.C.

1 Cf. the interesting but doubtful cases of Forth v. Chapman, 1 P. Wms. 663, involving different interpretations of the same expression by different court systems, and Bones v. Booth (1778) 2 W.BI. 1226, involving a difference between penal and non-penal application of a given expression. Both were mentioned in Maxwell on the Interpretation of Statutes, 6th ed., pp. 558-560, but have disappeared from more recent editions. The case of a single generic expression comprehending several species is of course a different one.

1 Edvard Hambro, 'Will the Revised Rules of Court Lead to Greater Willing¬ness on the Part of Prospective Clients?', in Leo Gross (ed.),The Future of the International Court of Justice, 1976, p. 368.“