No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

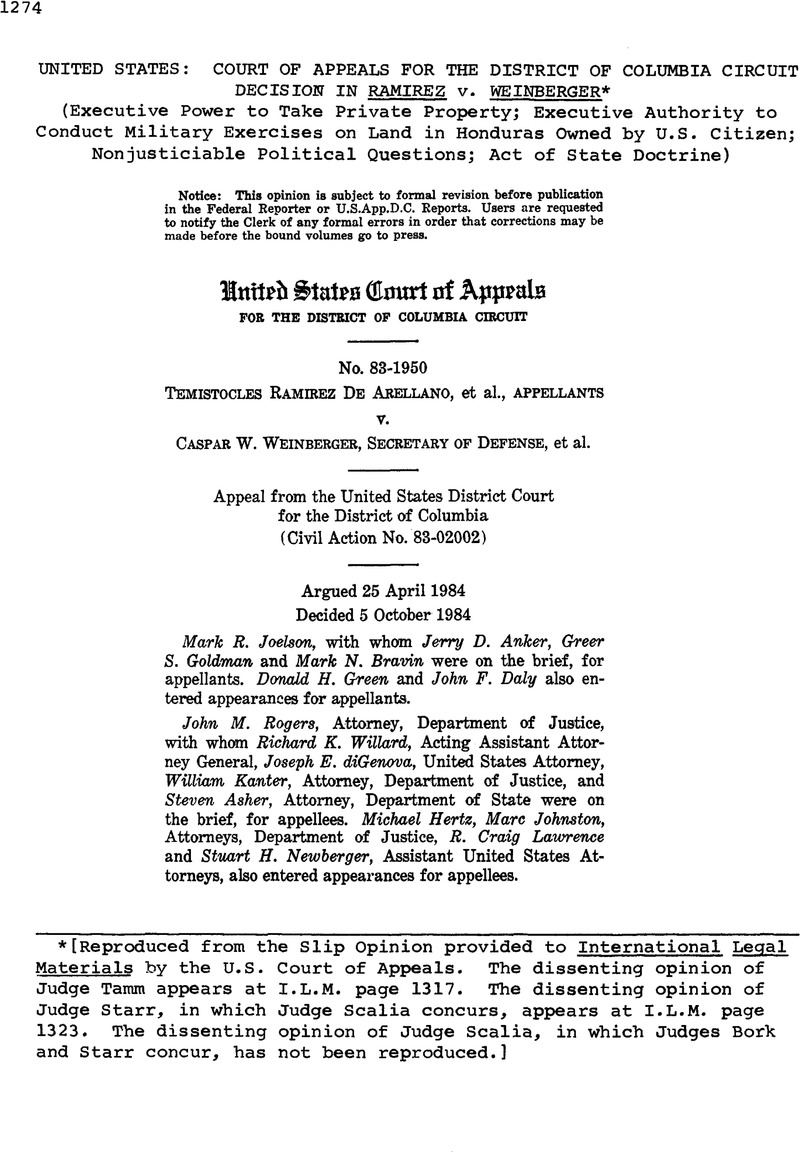

United States: Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit Decision in Ramirez v. Weinberger (Executive Power to Take Private Property; Executive Authority to Conduct Military Exercises on Land in Honduras Owned by U.S. Citizen; Nonjusticiable Political Questions; Act of State Doctrine)*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1984

Footnotes

[Reproduced from the Slip Opinion provided to International Lecral Materials by the U.S. Court of Appeals. The dissenting opinion of Judge Tamm appears at I.L.M. page 1317. The dissenting opinion of Judge Starr, in which Judge Scalia concurs, appears at I.L.M. page 1323. The dissenting opinion of Judge Scalia, in which Judges Bork and Starr concur, has not been reproduced.]

References

1 568 F. Sapp. 1236 (D.D.C. 1988).

2 Schuler v. United States, 617 F.2d 605, 608 (D.C. Cir. 1979) (quoting Conley v. Gibson, 355 U.S. 41, 45-46 (1957) ) (emphasis added).

3 Shear v. National Rifle Ass’n, 606 F.2d 1251, 1253 (D.C. Cir. 1979) ; Schuler v. United States, 617 F.2d at 608 (D.C. Cir. 1979).

4 Complaint ¶¶ 4-9, Appendix (“A.”) at 5-7 ; Ramirez Declaration ¶¶ 1-5, A. at 19-22. He compliant states that Ramirez owns two United States corporations which in turn own four Honduran corporations. “Hie six corporate plaintiffs … are and at all material times have been owned and controlled by Mr. Ramirez.” Complaint ¶ 5, A at 6.

5 Ramirez Declaration 4, A at 22.

6 Complaint ¶¶ 4-9, A. at 5-7; Ramirez Declaration ¶¶ 1-5, A. at 19-22.

7 See Plaintiffs' Memorandum of Points and Authorities, filed 13 July 1983, Attachment #1, Boston Globe, 27 Mar. 1983, at 1, A. at 15; id., Attachment #3, Miami Herald, 12 Apr. 1983, at 17-A, A. at 17.

8 See id., Attachment #3, Miami Herald, 12 Apr. 1983, at 17-A (“Honduras balks at hosting Salvador army training”), A. at 17; id., Attachment #2, N.Y. Times, 20 Mar. 1983, at A19, A. at 16.

9 Ramirez Declaration ¶ 24, A at 31; Ramirez Supplemental Declaration ¶ 3, A at 66.

10 Ramirez Declaration ¶ 10, A at 23.

11 Id. ¶¶ 19, 31, A at 28, 32-34; Ramirez Supplemental Declaration ¶¶ 22,29, A at 73-74,76.

12 Ramirez Declaration ¶ 33, A. at 34.

13 Reyes Declaration ¶4, A. at 94-95.

14 Complaint ¶11, A. at 8; Ramirez Third Supplemental Declaration ¶ 2, A. at 115.

15 Ramirez Declaration ¶ 6, A. at 22–23.

16 Ramirez Supplemental Declaration, Attachment #1; Brief of Appellees, Addendum A.

17 Ramirez Supplemental Declaration ¶ 2, A. at 65.

18 Complaint ¶ 11, A- at 8-10; Ramirez Declaration ¶¶13, 16-18, A. at 25-28.

19 Ramirez Declaration ¶ 36, A. at 36-37.

20 A. at 5-14.

21 See Transcript of 15 July 1983 at 4-11,36.

22 See Transcript of 15 July 1983 at 4-11,36.See Transcript of 26 July 1983 at 9, 11-12 (The Court said: “Summary judgment is a technique to resolve disputes as a matter of law when there is no dispute as to a material fact, and it is quite obvious here, I think both parties would agree, that there are some essential disputes as to the material facts in the case.”); 568 F. Supp. at 1237 n.l.

23 See Brief of Appellees, Addendum C.

24 Id. at c-5, c-7, c-8.

25 See Reply Brief of Appellants, Appendix A. We note that foreign law is a question of fact

27 Complaint ¶ 16, A. at 11.

28 See Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579 (1952); Hooe v. United States, 218 U.S. 322 (1910); The Paquete Habana, 175 U.S. 677 (1900).

29 343 U.S. 579 (1952). The purported distinctions of Youngstown Sheet & Tube offered by the dissenters merely serve to emphasize the applicability of that case to this. We suggest that the Supreme Court did not regard the foreign affairs component of seizing domestic steebnills as “nil”; the motive and justification for the presidential action was alleged to be a major war going on in Korea. In both Youngstownand the case today the “primary” effect of the seizure (Dissenting Opinion of Tamm, J., at 8) is on the property of United States citizens—foreign affairs powers have only been cited secondarily as a supposed justification for the domestic actions.

Further, whether the underlying activity enjoined is in Youngstown, Ohio and every other distant point in the United States where a seized mill was located, or at no greater distance to the South in a neighboring country, the location of the enjoined activity misses the mark. As the injunction running to the Secretary of Commerce in Youngstown illustrates, when the enjoined defendant is a responsible government officer residing in the nation's capital, who by virtue of his oath of office is sworn to uphold the Constitution and laws of the United States, and who therefore must be presumed to be ready to comply with this court's orders (as Government counsel conceded readily at oral argument before the original panel that defendants were willing and bound to do), questions of evaluating and guaranteeing compliance are not insurmountable.

finally, the availability of monetary compensation is always a factor in considering injunctive relief; not only is its availability doubtful here, but the plaintiffs' description of the situation may suggest that mere monetary relief would be insufficient under any concept of justice. See infra notes 124 & 134.

30 Id. Similarly, in The Paquete Hdbana, 175 U.S. 677, 710- 11 (1900), the Supreme Court held that the wartime capture of foreign fishing vessels off the coast of Cuba by U.S. officials was unlawful because such seizures had not been authorized by Congress.

31 339 U.S. 306, 313 (1950) ; see also Fuentes v. Shevin, 407 U.S. 67 (1972).

32 The third count chargee the defendants with violating the Law of Nations and is brought under the Alien Tort Claims Act, 28 U.S.C. § 1350 (1982).

33 369 U.S. 186 (1962).

34 444 U.S. 996, 998 (1979) (Powell, J., concurringr).

35 See, e.g., Luther v. Borden, 48 U.S. (7 How.) 1 (1849).

36 See, e.g., Metzenbaum v. FERG, 675 F.2d 1282, 1287

37 389 U.S. 768,789 (1950).

38 369 U.S. at 211.

39 See, e.g., Meigs v. McClung's Lessee, 13 U.S. (9 Cranch) 11 (1815).

40 See, e.g., United States v. Caltex (Philippines), Inc., 344 U.S.149 (1962).

41 348 U.S. 579 (1962).

42 See Pmcett v. McCormack, 396 U.S. 486, 548-49 (1969) (requirements of nonj ustidability not met when court is calledupon merely to interpret the Constitution);Consumer Energy Council of America v. FERC, 673 F.2d 425, 452 (D.C. Cir. 1982), affirmed mem. sub nom. Process Gas Consumers Group v. Consumers Energy Council of America, 103 S. Ct. 3556 (1983).

43 568 F. Supp. at 1239 (footnote omitted).

44 See Halkins v. Helms, 690 F.2d 977, 990 (D.C. Cir. 1982).

45 684 F.2d 928, 951 (D.C. Cir. 1982), cert, denied, 103 S. Ct 817 (1983).

46 369 U.S. at 217.

47 521 F.2d 284 (5th Cir. 1975), cert, denied, 424 U.S. 954 (1976).

48 720 F.2d 1355 (D.C. Cir. 1983) (per curiam), cert, denied,104S. Ct 3533 (1984).

49 See Goldwater v. Carter, 444 U.S. 996, 1004 (1979) (Rehnquist, J., concurring) (Justice Rehnquist noted that the claim in Youngstown was not a non justiciable political question because “[i]n Youngstown, private litigants brought a suit contesting the President's authority under his war powers to seize the Nation's steel industry.” ).

50 See Te–Oren v. Libyan Arab Republic, 726 F.2d 774, 796- 98 (D.C. Cir. 1984) (Edwards, J., concurring); id. at 803 n.8 (Bork, J., concurring) (“That the contours of the doctrine are murky and unsettled is shown by the lack of consensus about its meaning among the members of the Supreme Court ”) ; Vander Jagt v. O’NeiU, 699 F.2d 1166, 1173-74 (D.C. Cir.), cert, denied, 104 S. Ct 91 (1983); McGowan, Congressmen in Court: The New Plaintiffs, 15 Ga. L. Rev. 241, 256-60 (1981). Professor Louis Henkin suggested in his influential article debunking the political question doctrine and: the leading cases foreswearing judicial review on the ground that the issue posed was a political question might instead be understood as determinations that the challenged actions were in fact constitutional. See Henkin, Is There A “Political Question” Doctrine?, 85 Yale L.J. 697 (1976).

51 See, e.g., Goldwater v. Carter, 444 U.S. 996 (1979).

52 369 U.S. 186,217 (1962).

53 299 U.S. 304 (1936).

54 After reviewing1 the series of statutes relevant to the exercise of Executive {rawer, the Supreme Court concluded that “this, court may not, and should not hesitate to declare acts of Congress, however many times repeated, to be unconstitutional if beyond all rational doubt it finds them to be so.” Id. at 327.

55 Id. at 319.

56 Reid v. Covert, 354 U.S. 1,16 (1957).

57 299 U.S. 304 (1936).

58 333 U.S. 103 (1948).

59 Hie theory proposed by the dissent is equally applicable to other forums. Thus it is seriously doubtful whether any judicial remedy for the asserted taking would be available. See, e.g., Langenegger v. United States, slip op. (Claims Court 14 May 1984) (denying review on alternative theory of impermissible inquiry into foreign affairs when plaintiff's claim was unavoidably predicated upon a challenge to the intrusive manner in which the United States conducted its foreign policy) . Judge Tamm's apparent assumption that a remedy would exist in the Claims Court under the Tucker Act may be incorrect Dissenting Opinion of Tamm, J., at 10-11. of course, the possibility of a private bill of relief may theoretically be available. But see P. BATOR, P. MISHKIN, D. SHAPIRO & H. WECHSLER, HART & WECHSLHS'S FEDERAL COURTS IN THE FEDERAL SYSTEM 1326-31 (2d ed. 1973) (original purpose of Tucker Act to end the plague of private relief bills dogging Congress).

60 Further obfuscation is supplied by Judge Scalia's dissent, which concedes in his first paragraph on standing that Ramirez as an individual “has a cognizable property interest in that land, which interest, since he is an American citizen, is protected by the Constitution.” Dissenting Opinion of Scalia, J., at 13. The dissent then spends six more pages trying to place the interest of the wholly owned corporations exclusively under Honduran law. If the 100% owner, Ramirez, has an interest protected by the United States Constitution as Judge Scalia concedes, that is enough to compel the United States District Court to go forward, as we make clear in text at notes 55-56. Judge Scalia has conceded the only issue on this point we reach and decide

61 Berkey v. Third Ave. Railway Co., 244 N.Y. 84, 155 N.E. 58,61 (1926).

62 As such, cases involving corporate shareholders' attempts to sue for a violation of a constitutional right which attaches only to individuals when the challenged action affected onlythe corporation are inapposite. See, e.g., Reamer v. Beau, 506 F.2d 1345 (4th Cir. 1974), cert, denied, 420 U.S. 955 (1975) ; United States v. Richardson, 469 F.2d 349 (10th Cir. 1972). The approach, taken in the instant case is consistent with the holdings of those cases by its focus on the nature of a United States shareholder's personal interests and injuries and his own constitutional rights in determining whether the shareholder has a right to sue.

63 Cf. Cardenas v. Smith, slip op. (D.C. Cir. Apr. 17, 1974). Neither do we find it necessary now to resolve the issue whether the Honduran corporations may state a valid alternate claim under the Alien Tort Claims Act, 28 U.S.C. § 1350 (1982) ; see Verified Complaint for Declaratory and Injunctive Relief, Count III, A. at 5.

Judge Scalia, in dissent, mixes the two branches of standing together. As an initial matter, on the second branch he would hold that the foreign corporations have “no rights under the United States Constitution with regard to activity taking place in Honduras.” Dissenting Opinion of Scalia, J., at 13. Logically, therefore, he would also assert that no derivative corporate rights in the assets based on the United States Constitution may be passed on to United States shareholders. The remainder of the opinion, however, then attempts to define the direct constitutional rights of the United States citizen- shareholder by reference to the procedural and substantive rights of shareholders under Honduran law. In effect, the dissent permits the “efficiencies” and technicalities of Honduran corporation law (which are policies designed to regulate the affairs between Honduran corporations, the shareholders and creditors under Honduran law—not United States law) to de-fine the substantive scope of United States constitutional safeguards running directly to United States citizens (which safeguards, in turn, control the lawfulness of coercive power exercised upon the citizenry by the Government).

It seems to us that these two considerations are wholly unrelated; and that, at least when the issue of asserting a third party's rights does not cast doubt on the existence of a justiciable case-or-controversy—as might occur when a shareholder is attempting to assert derivative rights which can undisputably be raised by a corporation—it is improper to analyze the existence of a cognizable constitutional right as the dissent suggests. See infra note 79.

The dissent does not doubt that an individual United States citizen could assert the constitutional rights the plaintiffs now press. What the dissent attempts to create is a system in which a United States citizen loses all United States rights in wholly owned assets when those assets are held through a foreign corporation—perhaps even when the assets are located in the United States, since it is solely the “law of incorporation” (Dissenting Opinion of Scalia, J., at 17) which is said to define the United States constitutional rights. This is unsound and fundamentally unjust For instance, many foreign countries forbid direct ownership of real property by aliens, effectively forcing a United States national to adopt a foreign business entity to hold the investment. But the adoption of a foreign business entity should not be held to strip the United States citizen of rights he or she would otherwise have vis-a-vis the United States government in United States courts since stripping those rights would not serve any valid policy underlying the foreign rules of incorporation. Cf. RESTATEMENT (REVISED) OP THE FOREIGN RELATIONS LAW OF THE UNITED STATES § 216, reporters' note 3: “A state cannot, by requiring a foreign enterprise to incorporate locally, compel the corporation to surrender in advance its right to protection by the state of the parent corporation or of the parent's shareholders.” (Tent Draft No. 2,1981).

Moreover, the corollary to Judge Scalia's position is not true: a United States citizen cannot escape the prescriptive reach of United States law solely by choosing to do business through a foreign corporation. In many contexts the UnitedStates government has asserted control over foreign corporations owned predominately by United States shareholders. SeeRESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF THE FOREIGN RELATIONS LAW OF THE UNITED STATES § 27, comment d (1965):

When the nationality of a corporation is different from the nationality of the persons (individual or corporate) who own or control it, the state of the nationality of such persons has jurisdiction to prescribe, and to enforce in its territory, rules of law governing their conduct. It is thus in a position to control the conduct of the corporation even though it does not have jurisdiction to prescribe rules directly applicable to the corporation.

See also id. reporters' note. Constitutional rights and duties are closely related in scope; if the Constitution permits such a broad exercise of prescriptive power, then the protective reach of the Constitution should extend equally far.

64 See supra note 4.

65 See Warth v. Seldin, 422 U.S. 490, 500 (1975).

66 See Cardenas v. Smith, slip op. at 11 (D.C. Cir. April 17, 1984) ; Currie, Misunderstanding Standing, 1981 S. Ct Rev. 41,43.

67 11 Fletcher, W., Cyclopedia op the Law of Private Corporations § 5100 (1971 ed.)Google Scholar (footnotes omitted);see also Henn, H. & Alexander, J., Laws of Corporations 1052 (3d ed. 1083) (“Actions to enjoin a … sale of corporate assets have been permitted as direct actions. They are hardly actions to procure a judgment in favor of the corporation.” Google Scholar(footnotes omitted) ).

68 424 F.2d 833,843 (B.C. Cir. 1970).

69 419 U.S. 102,117 (1974).

70 343 U.S. 156,159-60 (1952).

71 417 U.S. 703,713 (1974).

72 103 S. Ct 2591 (1983).

73 Id. at 2601 (footnotes omitted).

74 We need not consider under what circumstances a shareholder should be deemed to have ceded his right to sue to the corporation by virtue of local law. It is sufficient to note thata shareholder will not be deemed to have ceded constitutional claims to an alien corporation which itself may be precluded from bringing suit on behalf of its shareholders. Furthermore, this is not a case in which the rights of other shareholders might be adversely affected by permitting a single shareholder to sue, because Ramirez has alleged that he is the sole ultimate beneficial owner.

75 408 U.S. 564, 571-72 (1972). Judge Scalia's dissent agrees that Ramirez has standing to vindicate his possessory interest in the ranch as a resident under Honduran law. (Dissenting Opinion of Scalia, J., at 13). We question the internal consistency of that concession with those portions of the dissent which assert, incorrectly, that Honduran law must define the scope of Ramirez’3 United States constitutional rights since the dissent has disclaimed any real knowledge of Honduran law and has explained the existence of the “lawful possessory interest under Honduran law” only by citing a decision by the United States Supreme Court Be that as it may, it seems that the concession of standing must be read to encompass all properties here in dispute, especially since the dissent has not cited to anything which would indicate that Ramirez's own possessory interest is not owned through a corporate intermediary, as is the rest of the ranch.

76 407 U.S. 67 (1972).

77 That constitutional provisions protecting property extend to property interests not secured by actual legal title was likewise made clear in Armstrong v. United States, 364 U.S. 40 (1960). In that case, the Court held that the plaintiffs had a property interest protected by the fifth amendment's just compensation clause when the value of liens which they held on boats and materials was destroyed by the government and in Mennonite Board of Missions v. Adams, 103 S. Ct 2706 (1983), the Court held that a mortgagee possesses a “substantial property interest” in the mortgaged property which is protected by the due process clause.

78 See, e.g., 22 U.S.C. § 2370(e) (1) (1982) ; infra notes 169, 170.

79 Judge Scalia's dissent adopts the defendants' argument and supports it by two evasive theories designed to avoid United States jurisdiction at all costs. The first is the argument refuted in the text above, that because Ramirez and his two solely owned Puerto Rican corporations have chosen to use wholly owned Honduran corporate vehicles in the ownership and operation of the Ramirez enterprise in Honduras, then American citizen Ramirez as a sole owner stockholder is relegated to the law of Honduras to determine what rights he can assert in a United States Court for violations allegedly carried out solely by American officials, military and civilian. We are familiar with the assertion that a party may properly be required to assert its United States constitutional rights in state rather than federal courts, since state courts are fully integrated in our nation's uniquely federal judicial system and are usually subject to review by the Supreme Court But heretofore we never thought that a United States party could be banished to the final and unreviewable forum of a foreign nation for a conclusive adjudication of that party's rights under United States law.

As indicated in the text above, to allow this argument to prevail would undermine the legal position of American multinational corporations around the world, as well as that of the United States government when it comes to their defense. For if the corporate form adopted can negate an American investor's rights against American officials, a fortiori the adoption of a local corporate form might be interpreted to negate his rights under international or local law against the actions of local officials.

The second evasive theory is the repeated assertion throughout the dissent that this whole training operation is a Honduran affair, that complaint should be made to the Hondurangovernment, and that United States citizen Ramirez's rights must be determined by Honduran law. This is answered by the FACTS—undeniable as alleged by the plaintiffs after this Rule 12(b) (6) disposition by the trial court—that plaintiffs have alleged no wrongful acts by Honduran officials under any law but have alleged wrongful acts by United States officials in violation of the United States Constitution, and that plaintiffs have named no Honduran officials but have named three United States officials within a five-mile radius of this courthouse as defendants. The plaintiffs' case against the United States defendants must be tested by United States law in a United States court.

All we decide here are the rights of a United States citizen, Ramirez, and his 100% owned corporations. We do not pronounce on the rights of a United States citizen owning .0001% of the shares in a Honduran corporation. Most of Judge Scalia's standing1 discussion, resting- on his analysis of shareholders' rights, is thus beside the point.

We do note, however, that his analysis would apparently permit the United States Executive Branch literally to do anything to the property and livelihood of a United States citizen overseas, if the United States citizen were conducting his business operations in the form of a foreign subsidiary corporation, without any recourse whatsoever to a United States District Court to protect his rights. United States constitutional rights are not so fragile.

80 Counsel for the Appellees, oral argument 25 Apr. 1984; see also Brief of Appellees at 5-8.

81 See, e.g. Swarm v. Charlotte-Mecldenburg Bd. of Educ.,402 U.S. 1,15 (1971). Courts are, of course, more reluctant to utilize their equitable powers for interim orders—when the plaintiffs have not yet proved their claims—than they are to grant equitable remedies for the correction of proved unlawful conduct In Adams v. Vance, 570 F.2d 950 (D.C. Cir. 1978), for example, the court required the plaintiffs to make an extraordinarily strong showing in order to justify a highly intrusive preliminary injunction against the Executive, when no constitutional violation had yet been proved.

82 Lemon v. Kurtzman, 411 U.S. 192, 200 (1973).

83 See Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Edue., 402 U.S. 1,15-16 (1971).

84 See Hecht Co. v. Bowles, 321 U.S. 321, 329-30 (1944) (a court of equity has flexibility to mold decrees to the particulars of each case).

85 See Developments in the Law—Injunctions, 78 HARV. L. REV. 996-1054 (1965); cf. RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OP TORTS §936 (1977).

86 See 28 U.S.C. §§ 1346,1491 (1982).

87 419 U.S. 102, 127 n.16 (1974) (quoting Hooe v. United States, 218 U.S. 322,336 (1910)).

88 218 U.S. 322 (1910). In United States v. North American Transp. Co., 253 U.S. 330, 334 (1920); Justice Brandeis held for the Court that the actions of a federal official who took land for military purposes were unauthorized and therefore created no liability for compensation by the government in the Court of Claims; see also Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579, 585 (1952) ; sources cited supranote 87 ; cf. The Paquete Habana, 175 U.S. 677, 710-11 (1900).

89 See Land v. Dollar, 330 U.S. 731,738 (1947).

90 See Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579, 595-96 (1952) (Frankfurter, J., concurring).

91 For example, in United States v. Causby, 328 U.S. 256 (1946) the Supreme Court held that a Tucker Act claim had been stated when the Civil Aeronautics Board, acting within the scope of authority granted to it by Congress, prescribed an air traffic route that was found to result in the taking of an easement over the plaintiff's land. Although Congress itself had not expressly put that particular airspace into the public domain, the taking was held to be authorized by Congress because it was within the discretion of the Civil Aeronautics Board, under the congressional statute, to prescribe an air traffic route like the one at issue Portsmouth Harbor Land & Hotel Co. v. United States, 250 U.S. 327 (1922), also supports this principle. The Court stated that because the military officials were authorized to build the fort in question and to staff it with guns and men, it would be reluctant to find lack of authority for the firing of the cannons which resulted in the property damage. Nonetheless, it remanded the case to the Court of Claims for a determination whether there was in fact authority on the part of the military officials so to fire the cannons sufficient to bind the government to pay for the property taken.

92 See sources cited supra notes 87 & 88.

93 634 F.2d 521 (Ct Cl. 1980), cert, denied, 451 U.S. 937 (1981).

94 Id. at 526 n.8.

95 Judge Scalia's dissent is largely in agreement with these principles; it relies on Larson v. Domestic & Foreign Corp.,837 U.S. 682, 696-705 (1949), which held that a challenge to the actions of a government officer asserting either (1) that the actions were “not within the officer's statutory powers,” or (2) that those statutory “powers, or their exercise in the particular case, are constitutionally void” need not be brought under the Tucker Act 337 U.S. at 702. However, although promising a “walk to the statutes and regulations and some hard thought” he never considers whether there exists anystatutory authorization for the kind of taking alleged to have occurred here, or whether that authorization—if there is any—would be consistent with Hie Constitution. Nowhere in the entire dissenting opinion is there an attempt to show that the Secretary of Defense, Secretary of States or the Chief of the United States Army Corps of Engineers has statutory authority or constitutional power to move troops in on a United States citizen's property anywhere, conduct life threat-ening military exercises, destroy the existing business enterprise, and thus effectively seize his property—all without notice to the citizen or the filing of any court or administrative action. Although both of these issues were contested before the district court and again on appeal, the dissent is willing to assume, sub silentio, the requisite statutory and constitutional authority.

That omission is particularly troublesome given the dissent's blanket assertion that “there is no violation of constitutional rights so long as just compensation is available.” (Dissenting Opinion of Scalia, J., at 3). Apparently the dissent endorses monetary ratification of unconstitutional and unauthorized governmental activities with no opportunity to correct the constitutional breach through the traditional injunctive powers of the courts. Under this approach the government can deprive a citizen of any possession, and the citizen cannot challenge the government's right to do it, but only question how much the citizen is to receive for losing his property.

This cannot be the law. On any type of taking by the government, the citizen can always raise the threshold question, whether successfully or unsuccessfully, of the government's fundamental right to take his property. Then, and then only, if the government establishes its constitutional right to seize the property of the citizen, is the citizen relegated to the second question, i.e., how much should the plaintiff be compensated for the property which was taken. The fundamental first question of constitutional right to take cannot be evaded by offering “just compensation.”

96 Nor may Congress have intended so to tax the public coffers under the Tucker Act for such unauthorized activities. Congress has provided that acquisition of private property is beyond the authority of military officials unless it is expressly permitted by law. “No military department may acquire property not owned by the United States unless the acquisition is expressly authorized by law.” 10 U.S.C. § 2676 (1982).

97 No. 82-2304 slip op. (D.C. Or. 17 Aug. 1984).

98 Id. at 5 (quoting Schnapper v. Foley, 667 F.2d 102, 107 (D.C. Cir. 1981), cert, denied, 455 U.S. 948 (1982)). 1295

99 Id. at 6. It is generally accepted that this waiver extends to suits brought under 28 U.S.C. § 1331 (1982), one of the jurisdictional bases asserted in this suit See Dronenburg,slip op. at 6 n.3 and authorities cited therein.

100 See Dronenbwrg, slip op. at 6 (quoting S. Rep. No. 996, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 7-8 (1976) ).

101 See also Megapulse, Inc. v. Lewis, 672 F.2d 959, 971 (D.C. Cir. 1982).

102 Tucker Act confers jurisdiction over claims against the United States ‘founded … upon the Constitution, or any Act of Congress,… or upon any contract with the United States.” 28 U.S.C. § 1491 (1982). Just as it might be argued that Ihe plaintiffs in Dronenbwrg and Megapulse did not assert traditional contract claims within the scope of § 1491, (See Megapulse Inc. v. Lewis, 672 F.2d at 968, 971 (1982)), the case at hand is not one seeking “just compensation” under the fifth amendment or otherwise “founded upon” the Constitution within the ordinary meaning of § 1491. Rather, it asserts that there is no underlying authority for the taking in either the Constitution or statutes of the United Sates. The claim thus clearly “arises under the Constitution, laws, or treaties of the United States.” 28 U.S.C. § 1331 (1982). Compare Dronenbwrg (D.C. Cir. 17 Aug. 1984) (asserted violation of constitutional privacy and equal protection rights not a claim subject to exclusive jurisdiction of Claims Court).

103 106 U.S. 196 (1882).

104 Id. at 219-21 (emphasis added). With reference to tyrannical “monarchies,” see Dissenting Opinion of Scalia, J., at 1 n.1; compare I Samuel 8:7-18, 12:17.

105 330 U.S. 731 (1946).

106 Id. at 737:

107 Id. at 738.

108 Larson v. Domestic & Foreign Corp., 337 U.S. 682, 698 (1949); Malone v. Bowdoin, 390 U.S. 643 (1963).

109 106 U.S. at 220.

110 337 U.S. at 697.

111 Id. at 697 n.18.

112 Malone v. Bowdoin, 369 U.S. 643, 647 (1962); Larson v. Domestic & Foreign Corp., 337 U.S. at 697 n.17.

113 285 U.S. 95 (1982).

114 Id. at 104 n.3 (citations omitted).

115 Id.

116 In fashioning equitable remedies, the issue of whether damages will adequately compensate plaintiffs for a claimed unconstitutional seizure of private property by unauthorized government officials is not equivalent to the fifth amendment's provision that the government lawfully may expropriate property for just compensation. The fifth amendment's requirement of just compensation for takings defines the government's lawful powers of eminent domain; it does not embody a remedial principle applicable in equity that monetary damages are fully adequate to redress injuries to real property.

The Court's opinion in Larson amply recognizes this principle.

There are limits, of course [to the reluctance of courts to invoke compulsive powers to restrain the Government from affecting disputed property]. Under our constitutional system, certain rights are protected against governmental action and, if such rights are infringed by the actions of officers of the Government, it is proper that the courts have the power to grant relief against those actions. But in the absence of a claim of constitutional limitation, the necessity of permitting the Government to carry out its functions unhampered by direct judicial intervention outweighs the possible disadvantage to the citizen in being relegated to the recovery of money damages after the event.

337 U.S. at 704 (emphasis added). Thus, a statute may be challenged as unconstitutional, and an injunction issued, when the compensation available under the Tucker Act would notrise to the level of just compensation required by the fifth amendment. Such a claim would fall within Larson's exception permitting injunctive relief if “the exercise [of statutory powers] in the particular case … [is] constitutionally void.” Id. at 702.

117 343 U.S. at 585.

118 See Ruckelshaus v. Monsanto County, 104 S. Ct 2862 (1984) (“ [A] n adequate remedy for the taking exists under the Thicker Act”); Dugan v. Rank, 372 U.S. 609, 623-24 (1963) (rejecting arguments that damages were inadequate since they could not be reasonably ascertained); Malone v. Bowdoin, 369 U.S. 643, 648 (1962) (not reaching the issue, since the plaintiff failed to assert that-just compensation was unavailable) ; cf. Larson v. Domestic & Foreign Corp., 337 U.S. 682 (adequacy of Tucker Act remedy for asserted wrongful retention of coal not questioned, since fungible personalty not ordinarily the subject of extraordinary injunctive relief).

119 See, e.g., Belusko v. Phillips Petroleum Co., 198 F. Supp. 140 (S.D. 111. 1961), aff’d, 308 F.2d 832 (7th Cir. 1962), cert, denied, 372 U.S. 930 (1963).

120 See Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579 (1962); Erhardt v. Boaro, 113 U.S. 537 (1885); Lucy Webb Hayes Natfl Training School for Deaconesses & Missionaries v. Geoghegan, 281 F. Supp. 116 (D.D.C. 1967); 6A J. SACKMAN, NICHOLS' THE LAW OP EMINENT DOMAIN § 28.3 (3d ed. 1981).

121 See supra note 15.

122 429 F.2d 1197 (2d Cir. 1970) (Judge Friendly found that monetary relief would not be adequate and that injunctive relief was proper to prevent the loss of a 20-year-old business managed by the owners).

123 See PotoeU v. McCormack, 395 U.S. 486, 550 (1969).

124 See, e.g., Kern v. Dulles, 357 U.S. 116, 129-30 (1958) ; Reid v. Covert, 354 U.S. 1 (1957) ; Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579 (1952). While Judge Scalia's dissent relies principally on trying to characterize this case as a land title dispute, to which Honduran law would apply to Honduran land, at one point he does venture to go further to confront the alleged facts that the actions of United States officials have not only been property taking but property destroying and life threatening, Judge Scalia's answer is: “As for the risk to plaintiff Ramirez's security: That is not a consequence of the taking, but of the plaintiff's refusal to acquiesce in it” (Dissenting Opinion of Scalia, J., at 29). If this is a fair characterization of the government's position, then the government's argument boils down to: “How dare the citizen's nose get in the way of the governmental fist?” As long as the plaintiffs' complaint plausibly alleges unconstitutional or unauthorized actions by governmental defendants, we think it ludicrous to suggest that the threat to plaintiff Ramirez's security is of his own making because he insists upon asserting his United States constitutional rights—against governmental actions which have never sought nor received the imprimatur of any court anywhere.

125 11 C. Weight & A. Miller, federal Practice & Procedure §§ 2942-45 (1973). See E. Messner, The Jurisdiction of a Court of Equity Over Persons to Compel the Doing of Acts, 14 Minn. L. Rev. 494, 500 (1930).

126 99 U.S. (9 Otto) 298, 308 (1879) (emphasis added).

127 See sources cited supra note 125.

128 Id.

129 See, e.g., United States v. Caltex (Philippines), Inc., 344 U.S. 149 (1952) (adjudicating a claim that United States military officials unlawfully destroyed private property in the Philippines).

130 See Reid v. Covert, 354 U.S. 1 (1957); Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579 (1952) ; Duncan v. Kahanamoku, 327 U.S. 304 (1946).

131 54 U.S. (13 How.) 115, 133 (1852) (emphasis added).

132 413 U.S. 1,11-12 (1973).

133 Sterling v. Constantin, 287 U.S. 378, 403 (1932) (federalism concerns and the context of executive action do not bar relief).

134 408 U.S. 1, 15-16 (1972).

135 It is instructive to compare Judge Scalia's doctrine of equitable discretion with that suggested in the Youngstowncase. In Youngstown the Supreme Court permitted the plaintiffs to attempt to establish an equitable basis for the requested injunction, primarily through a showing that money damages, if available, would not compensate for the injury. 343 U.S. at 584-85; Id. at 595-96 (Frankfurter, J., concurring). None of the Justices who found the seizure unconstitutional suggested that an inadequate damage remedy could substitute for injunctive relief if constitutional authority for the taking was not extant. In this case, however, Judge Scalia, in dissent, would deny the plaintiffs even an opportunity to show that damages could not fully compensate for their alleged loss; he merely assumes, without any factual foundation whatsoever, that any loss which might be proved is compensable. Apparently this does not trouble the dissent because it asserts that money damages are always sufficient to remedy an unconstitutional taking, and that, therefore, an “injunction is not available to prevent a taking by the United States” —presumably even one which the United States has no constitutional or statutory authority to make. Dissenting Opinion of Scalia, J., at 29 (discussing Larson).

If this were the law, the Supreme Court had nothing to decide in Youngstown, since the authority of the President to make the seizure would have been an irrelevant issue, the only question remaining being the extent of money damages to be paid for the taking. Preferring to ignore what it cannot overrule, the dissent thus takes a position even more extreme than that propounded by the dissenters in Youngstownwho were willing to assume that the Government “was not immnTi« from judicial restraint and that the plaintiffs are entitled to equitable relief if we find that the … [taking] is unconstitutional.” 343 U.S. at 678 (Vinson, C.J., dissenting).

136 Judge Scalia epitomizes the weakness of the government's position when he sums up his dissenting opinion argument against equitable relief :

[1] “Any system that would countenance judicial interference in military operations abroad”—are the United States military when they operate abroad never subject to the courts at the behest of United States citizens ?

[2]“for a reason that simultaneously impugns the integrity and fairness of a friendly nation”—a point never raised directly or by implication by the plaintiffs here. No accusation has been levied nor redress asked in U.S. courts against the Honduran government or any official thereof. Assuming that a seizure has occurred, even the Honduran government'sfailure, to date, to make a lawful expropriation and pay due compensation to the plaintiffs could be easily explained as the Honduran government's viewing this whole operation as a United States affair with the United States obligated to compensate its own citizen.

[3] “at the instance of a plaintiff who has not sought traditional judicial relief in the country where the real estate in question is located”—again, no complaint has been levied by the plaintiff against the Honduran government or any official; further, this is not a piddling land title dispute; and finally, regarding a dispute between a United States citizen and his own government, “traditional judicial relief” has never been in Honduran courts.

[4] “and who in any event has a claim for money damages in the courts of this country”—existence of monetary damages, if they do exist in this case, cannot bar equitable relief, as Judges Bork and Scalia have so recently stated. Droneriburg v. Zech, No. 82-2304 slip op. (D.C. Cir. 17 Aug. 1984).

In his elaboration of these points Judge Scalia makes much of the third, saying: “A further obstacle to issuance [of an injunction] is the fact that they have made no effort ... to obtain protection in the ordinary quarter from the trespass of which they complain—the courts of Honduras.” Dissenting Opinion of Scalia, J., at 27-28. This emphasizes the evasive nature of the defense relied on by the government brief and argument, which Judge Scalia supports. “The trespass of which they complain” comes from the United States Army. Belief from this particular trespass, and these particular trespassers, would not ordinarily be found in “the courts of Honduras.”

137 28 U.S.C. § 2201 (1982); E. BORCHARD, DECLARATORY JUDGMENTS 3-15 (2d ed. 1941); 10A C. WEIGHT & A MILLER, FEDERAL PRACTICE & PROCEDURE § 2751 (2d ed. 1983); See Developments in the Law—Declaratory Judgments, 62 HARV. L. REV. 787, 787-90, 874 (1949).

138 See Samuels v. Mackell, 401 U.S. 66, 69-74 (1971) (where state criminal prosecution had begun prior to federal suit, injunctive and declaratory relief had same effect and must be judged by the same standards).

139 See sources cited supra note 137.

140 See Laguna Hermosa Corp. v. Martin, 643 F.2d 1376, 1379 (9th Cir. 1981) (district court does not lose jurisdiction simply because its declaratory judgment may later become the basis for a manatory indement.

141 See Amalgamated Sugar Co. v. Bergland, 664 F.2d 818, 828-24 (10th Cir. 1981).

142 672 F.2d 959,966-69 (D.C. Cir. 1982).

143 On 28 September 1983 a panel of this court, sua aponte,requested suplemental briefs by the parties on the applicabilityof act of state doctrine to the facts of this case—an issue which had not been raised previously by the parties or the district court.

144 168 U.S. 250,252 (1897).

145 376 U.S. 398 (1964).

146 See First Naif’l City Bank v. Banco Nacional de Cuba, 406 U.S. 759, 775 (1972) (Powell, J. concurring in the judgment).

147 22 U.S.C. § 2370 (e) (2) (1982).

148 425 U.S. 682 (1976).

149 See First Naif’l City Bank v. Banco Nacional de Cuba,406 U.S. 759, 775-76 (1972) (Powell, J., concurring in the judgment).

150 Brief of Appellees, Addendum A.

151 Brief of Appellees, Addendum C at c-5 to c-8.

152 See A. at 98-113.

153 Reply Brief of Appellants at 8 n.2.

154 We disagree with the dissent's suggestion that one or more steps in the uncompleted process of expropriation must be accepted as evidence of an accomplished act of state. It is generally recognized that a conclusive foreign act must be completed before the doctrine is invoked. The doctrine has never been applied when it was uncertain whether a foreign expropriation had been effected. See, e.g., RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OP THE FOREIGN RELATIONS LAW OP THE UNITED STATES § 43 comment a (1965) (“[A]ct of state doctrine … becomes applicable only when and if the act has been fully executed.” (emphasis added)). Until it is shown that an officially sanctioned physical seizure has in fact occurred, or that the legal processes of expropriation have been terminated by the foreign government, partial governmental action does not necessarily result in an act of state.

155 See Compania Española de Navegadon Maritima v. Navemar, 303 U.S. 68 (1938) (district court properly took evidence on whether foreign government took possession of a merchant vessel by an act of dominion or control).

156 Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(b) (final sentence).

157 See generally 5 WEIGHT, C. & A. MILLER, FEDERAL PRACTICE & PROCEDURE § 1366 (1969)Google Scholar.

158 Local rules usually recognize the proper role played by the District Court For example, United States District Court Rules, D.C., provide that on each motion for summary judgment the movant must file a statement of the material facts and tiie opposing party shall then file “a concise 'statement of genuine issues' setting forth all material facts as to which itis contended there exists a genuine issue necessary to be litigated.” Rule 1-9 (h). Plaintiffs were not afforded these procedural rights.

159 E.g., Irons v. Schuyler, 465 F.2d 608 (D.C. Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 1076 (1972).

160 Tarpley v. Greene, 684 F.2d 1, 7 (D.C. Cir. 1982); Frank C. Bailey Enter's v. Cargill, Inc., 582 F.2d 333, 334 (5th Cir. 1978).

161 Fed. R. Civ. P. 12 (b), 28 U.S.C.A.

162 Id.

163 See Sadlowski v. United Steelworkers, 645 F.2d 1114, 1120 (D.C. Cir. 1981), rev'd on other grounds, 457 U.S. 102 (1982) ; BlackhawkH eating & Plumbing Co. v. Driver, 433 F.2d 1137 (D.C. Cir. 1970) ; Ithaca College v. NLRB, 623 F.2d 224, 229 (2d Cir.), cert, denied, 449 U.S. 975 (1980) ; E.C. Ernst, Inc. v. General Motors Corp., 537 F.2d 105, 109 (5th Cir. 1976). The cases cited in Judge Starr's dissent permitted a conversion only when the record and the issues as framed by the parties squarely raised the dispositive issue. See Brookens v. United States, 627 F.2d 494, 497-99 (D.C. Cir. 1980) (nonprevailing party had challenged the defendant at the trial court level to prove an admittedly dispositive fact, and subsequent affidavits responded to that challenge) ; Gager v. “Bob Seidel,” 300 F.2d 727, 731 (D.C. Cir.), cert, denied, 370 U.S. 959 (1962) (complaint put the scope of defendants' immunity to suit precisely in issue). The suggestion that the court of appeals may indiscriminately “treat the matter as one involving a grant of summary judgment, regardless of the characterization by the district court of its disposition of the matter” (Dissenting Opinion of Starr, J., at 2 n.2) has never been the law in this Circuit, and certainly is not after our decision today.

164 336 U.S. 681 (1949).

165 Even Judge Tamm, in dissent, agrees that further factual development is required before drawing any legal conclusions on the occurrence of an act of state. See Dissenting Opinion of Tamm, J., at 2 n.3. Judges Starr and Scalia are alone in their willingness to find the facts necessary to create an act of state.

166 Fed. R. Civ. P. 56.

167 United States v. Diebold, Inc., 369 U.S. 654, 655 (1962); Poller v. Columbia Broadcasting Sys., 368 U.S. 464, 473 (1962); Ring v. Schlesinger, 502 F.2d 479, 490 n.16 (D.C. Cir. 1974).

168 Transcript of 26 July 1983. at 11.

169 See 22 U.S.C. § 2370(e) (1) (1982).

170 Dissenting Opinion of Starr, J., at 2.

With all respect to the dissent's professed astonishment, Judge Starr's assertion that “[i]t cannot seriously be argued that a cut-off of financial assistance is required” is answered by the simple, unambiguous, and detailed terms of the statute —and the whole purpose for which the statute was enacted.

The dissent adverts to no provision which would render the statute inapplicable. It is inconsequential that the land may be “hypertechnical[ly]” owned by the Honduran corporate plaintiffs, since the full statute (not cited in the text supraat note 169) prohibits foreign assistance when the corporation whose assets are seized is at least “50 per centum beneficially owned by United States citizens.” 22 U.S.C. § 2370 (e) 1 (A) (1982). Here, it is undisputed that the Honduran corporations are 100% beneficially owned by U.S. citizens.

Neither is it significant that an expropriatory decree may have issued. The statute itself stipulates the time limits for compensatory payment which must be met to avoid the mandate to freeze foreign aid.

Finally, the dissent answers its own objection that “[t]his is scarcely a Cuba-like retaliatory seizure of American assets”: the President himself may waive the strict standards of the Amendment after a determination and certification to Congress that a waiver is important to the national interests of the United States. Dissenting Opinion of Starr, J., at 15 & n.8. We would expect that provision to be invoked, rather than ignored, if United States interests would be jeopardized by an aid cutoff.

171 See Kalamazoo Spice Extraction Co. v. Provisional Military Government of Socialist Ethiopia, 729 F.2d 422 (6th Cir. 1984) ; American Inf I Group, Inc. v. Islamic Republic of Iran, 493 F. Supp. 522 (D.D.C. 1980).

172 See Banco National de Cuba v. Sabbatino, 376 U.S. 398 at 430 n.34.

173 Id. at 428 (emphasis added).

174 See 45 Stat 2618,2619.

175 See Brief of Appellees, Addendum E at e-2. “Just, adequate, and effective compensation” is the standard of the First Hickenlooper Amendment, supra, note 169.

176 See Brief of Appellees, Addendum E at &-2. of course it is possible that this fact may be disputed on remand by the defendants.

177 See supra note 172.

178 22 U.S.C. § 2370(e) (2) (1982).

179 The statute provides that the act of state doctrine may not apply if a

country, government agency, or government subdivision fails within a reasonable time (not more than six months after such action …) to take appropriate steps, which may include arbitration, to discharge its obligations under international law toward such citizen or entity, including speedy compensation for such property in convertible foreign exchange, equivalent to the full value thereof, as required by international law ....

Id. § 2370(e)(1).

180 We reject the dissent's suggestion that the word “property” in. the statute must invariably be limited to expropriated personal property located in the United States. It is based only on authority which has been overturned in the Supreme Court See Banco National de Cuba v. First Nafl City Bank,431 F.2d 394, 399-402 (2d Cir. 1970), vacated and remanded, 400 U.S. 1019 (1971), afFd on remand, 442 F.2d 530 (2d Cir. 1971), rev'd on other grounds, 406 U.S. 759 (1972) ; Compania de Gas de Nuevo Laredo, S.A. v. Entex, 686 F.2d 322, 327 (5th Cir. 1982), cert denied, 103 S. Ct 1435 (1983) (relying solely on Banco National de Cuba). By no twist of legal imagination can the Supreme Court's reversal (of the Second Circuit's general holding that the act of state doctrine controlled the case) constitute approval of the reasoning relied on by the court of appeals with respect to the meaning of the Second Hickenlooper Amendment. The statute must be read consistently with congressional intent, and might not apply to every expropriation of foreign property owned by United States citizens. It may be that a primary purpose of the statute was to prevent invocation of the act of state doctrine when property expropriated in a foreign country subsequently makes its way into the United States, but this was not the sole situation in which the amendment was to be activated. There was some concern in Congress that the amendment could be read to create a new, expanded right of action to challenge all foreign expropriations in United States courts, even when the traditional basis of jurisdiction—attachable property located in the United States—was not present. Any statement in the legislative history suggesting that the amendment applied only to personal property in the United States was made in response to these fears and indicates merely that no new class of jurisdiction over expropriation cases was contemplated. See Foreign Assistance Act: Hearings on H.R. 7750 Before the Committee on Foreign Affairs, 89th Cong., 1st Sess. 592 (Q. 3), 607-611 (1965) [hereinafter cited as Hearings].

Moreover, the broad, unqualified language of the carefully drafted amendment belies the narrow reading offered by the dissent. The sponsors of the amendment referred to it as the “Rule of Law” amendment; they viewed it as authorizing courts to apply established law suits challenging expropriations. Congressional intent to overturn Sabbatino was never limited to a single narrow class of cases. The purposes of the amendment include the promotion and protection of United States investment in foreign countries (which characteristically has always principally been land, minerals, and large fixed immovables), and securing the right of a property holder to a court hearing on the merits. See Hearings, supra at 607- 610. Gutting the amendment by the addition of external language offered by the dissent would be inconsistent with these purposes and we decline to adopt it.

181 168 U.S. 250,252 (1897).

182 We cannot be sure that the expropriatory steps of the Honduran government would be raised even to this extent, since the defendants have not revealed the asserted legal justification for their activities. We of course express no view on whether this would be a justifiable defense.

183 Cf. Reid v. Covert, 354 U.S. 1, 16 (1957) (“[N]o agreement with a foreign nation can confer power on … any … branch of Government which is free from the restraints of the Constitution.”).

184 Continental Ore Co. v. Union Carbide & Carbon Corp., 370 U.S. 690, 704-05 (1962). See United States v. Sisal Sales Corp., 274 U.S. 268 (1927).

185 See United States v. Hensel, 699 F.2d 18 (1st Cir.), cert, denied, 103 S. Ct. 2431 (1983) (collaboration with Canadian authorities does not shield United States officials from claims alleging a violation of the fourth amendment by a search and seizure in Canadian waters); Berlin Democratic Club v. Rumsfeld, 410 F. Supp. 144 (D.D.C. 1976). The overruled and discarded case of American Banana Co. v. United Fruit Co., 213 U.S. 347 (1909) (discredited in United States v. Sisal Sales Corp., 274 U.S. 268 (1927), United States v. Aluminum Co. of Am., 148 F.2d 416 (2d Cir. 1945) is inapposite for several reasons. The legal issues raised in American Banana dealt only with the statutory scope of the Sherman Act, not the reach of the United States Constitution or the extent to which the United States government is bound by the Constitution when operating abroad. Factually, in this case it is alleged that the United States Army, not a foreign government, has seized the property. Moreover, unlike the situationin American Banana, the United States defendants' actions may have predated any Honduran act of state by many months. Plaintiffs allege that the United States defendants caused intrusions onto the plaintiffs' ranch as early as May 1983, and the seizure and destruction of the plaintiffs' property is alleged to have continued from that date to the present time. We doubt that any act of the Honduran government expropriating the plaintiffs' property months or even years later could operate to shield the United States defendants from liability for constitutional violations which allegedly occurred prior to the act of the foreign state.

186 The spirit of the Nation's historic commitment to protecting private citizens' rights against military excesses is embodied in the third amendment's express prohibition against the quartering of soldiers in private homes. “No Soldier aha.11, in time of peace be quartered in any house, without the consent of the Owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.” U.S. CONST, amend. III.

187 in E.g., The Prize Cases, 67 U.S. (2 Black) 635 (1863).

188 E.g., Youngstoum Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579 (1952) ; United States v. Lee, 106 U.S. 196 (1882).

189 Dissenting Opinion of Scalia, J.t at 32.

190 Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. (5 Dali.) 137 (1803).

191 106 U.S. at 218-23.

192 343 U.S. at 596 (Frankfurter, J., concurring:) (emphasis added).

1 The district court dismissed this case pursuant to FED. R. CIV. P. 12(b) (6). In granting a rule 12(b) (6) dismissal, a court must accept as true all allegations in the complaint and is not permitted to rely on pleadings outside the complaint. I therefore recite only the facts presented in the complaint and the accompanying declarations.

2 Although the majority notes newspaper articles suggesting that the Honduran government resisted the effort to locate the facility in Honduras, maj. op. at 6, other articles suggest that Honduras wanted a training center, Attachment # 2, N.Y. Times, Mar. 20, 1983, at A-19, col. , A at 16, 1317 or at least that the center would not have been built without Honduras's agreement. Attachment # 1, Boston Globe,Mar. 27,1983, at 1, col. A. at 15.

3 The Honduran government has passed two resolutions pertaining to the issue of expropriation. En Banc Brief for Appellees, Addendums A C. The legal implications of these resolutions have been addressed extensively in the majority's opinion. I agree with the majority's conclusion that we cannot ascribe any legal effect to these resolutions absent further factual development. Since I believe the controversy as presented in this case is not appropriate for judicial resolution, 1 see no need to discuss the effect of these Honduran resolutions or to seek further fact-finding to facilitate their interpretation

4 Indeed, plaintiffs could not seek such a remedy in the district court Exclusive jurisdiction for monetary relief against the United States in excess of $10,000 lies in the Court of Claims under the Tucker Act 28 U.S.C. §§ 1346, 1491 (a) (1982).

5 In Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962), the Court was primarily concerned with outlining the characteristics of issues nonjusticiable under the political question doctrine. The political question doctrine, in the strict sense, may pertain only to the nature of the question presented, and not to the effect of granting the relief requested. The same separation of powers concerns that give rise to the political question doctrine, however, are implicated where the effect of resolving a dispute infringes on the executive's conduct of foreign policy. See Tel-Oren v. Libyan Arab Republic, 726 F.2d 774, 804 (D.C. Cir. 1984) (Bork, J., concurring), petition for cert. fOed, 52 U.S.L.W. 3922 (U.S. June 14, 1984) (No. 83-2052). Just as a court must refrain from resolving a question whose nature is political, so must it refrain from adjudicating a claim where the relief sought would intrude on the independence of the political brandies.

6 In Chicago & Southern Air Lines, Inc. v. Waterman Steamship Corp., 333 U.S. 103 (1948), for example, the Court declined to review an administrative order, approved by the President, regarding assignment of foreign air routes. Although the complaint did not directly question a political judgment, the Court observed that assignment of foreign air routes raised issues concerning’ the conduct of foreign relations and national defense. Because the complaint indirectly, yet no less intrusively, challenged an executive judgment on foreign affairs, the Court held the order nonreviewable. 333 U.S. at 111-14.

7 Plaintiffs assert that they do not seek to enjoin generally the operation of a United States military facility but only the military activities on their land so long as that land has not been lawfully acquired. In either case, however, an injunction would have the same effect: halting the operation of a United States military facility in Central America, at least for a time.

8 The majority states that there is a “long: line” of cases permitting’ judicial relief for unlawful action by United States officials in the context of military and foreign affairs. Maj. op. at 56. In determining that the instant case is non justiciable, I do not conclude that courts can never adjudicate claims involving the conduct of foreign affairs. See supra at 7-9. Where, however, the consequence of judicial action intrudes directly upon the executive's ability to exercise discretion in foreign policy matters, the court must stay its hand. Significantly, the cases cited by the majority are either “just compensation” cases, in which the consequences of judicial action in no way impeded the exercise of executive discretion with respect to foreign affairs, e.g., United States v. Caltex (Philippines) , Inc., 344 U.S. 149 (1952); Mitchell v. Harmony, 54 U.S. (IS How.) 115 (1852); or arose in the domestic context, e.g., Gilligan v. Morgan, 413 U.S. 1 (1973); Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579 (1952); Duncan v. Kahanamoku, 327 U.S. 304 (1946); Sterling v. Constantin, 287 U.S. 378 (1932).

9 This point ia not undermined by this court's holding in Megapulse, Inc. v. Lewis, 672 F.2d 959 (D.C. Cir. 1982), a case relied upon by the majority. Megapulse properly recognized the importance of “preserving the integrity of the Tucker Act..id. at 967, and noted that a district court has no power to adjudicate an action that in essence falls within the Court of Claims' exclusive jurisdiction.

10 The original panel opinion in this case expressed similar separation of powers concerns with respect to the requestedrelief. Ramirez de Arellano v. Weinberger, 724 F.2d 143 (D.C. Cir. 1983), vacated, F.2d (1984). The panel's analysis, however, rested on the traditional discretion of courts to grant or deny injunctive relief depending on the relative equities of the parties' positions. The panel concluded that injunctive relief could not issue because intrusion into foreign affairs coupled with the possibility of impugning foreign law and the problems of monitoring compliance “establish a formidable obstacle which the equities of plaintiffs' case cannot overcome.” 724 F.2d at 150.

I cannot agree with the panel's reasoning. The panel's reliance on traditional principles of equity implies that were the plaintiffs' case more compelling, equitable relief might be appropriate. The panel's decision to affirm the dismissal, therefore, was not compelled by separation of powers principles but resulted from the court's exercise of its traditional equitable discretion. When there is a danger of a federal court exceeding its limited authority, constitutional principles of separation of powers, not a subjective assessment of the relative equities, should control a court's decision whether to resolve a controversy. See Vander Jagt v. O’Neill, 699 F.2d 1166, 1184- 85 (D.C. Cir.) (Bork, J., concurring), cert, denied, 104 S. Ct. 91 (1983).

Although I agree with Judge Scalia that constitutional issues ought to be avoided wherever possible, I believe Judge Scalia's dissent effectively reaches and employs the separation of powers doctrine under the guise of balancing equitable concerns. Scalia, J., dis. op. at 25-26 & n.13. I have chosen the tack presented in this dissent because I believe a forthright application of separation of powers principles precludes a court even from exercising such equitable discretion. Finally, balancing the equities in this case could require the court to evaluate the necessity and urgency of operating the Center in its current location. Such an evaluation is properly and practically better left to the political branches. I would thus dismiss plaintiffs' claim, not because of its adequate equitable support, but because it would carry the judiciary into matters reserved to the coordinate branches.

2 This case comes to us from the District Court's order granting defendants' motion to dismiss pursuant to FED. R. Civ. P. 12(b) (6). The procedural posture of the case, however, does not restrict this court to consideration of only those facts alleged in the pleadings filed in the District Court. This is because defendants' motion, styled in the alternative as one for dismissal or summary judgment, was converted into a motion for summary judgment by the actions of the parties and the District Court Specifically, the parties' filing of materials in addition to the pleadings, and the District Court's decision to accept and consider the proffered materials, worked this conversion under Rule 12(b) (6), according to well- established principles. Brookens v. United States, 627 F.2d 494,499 (D.C. Cir. 1980); Irons v. Schuyler, 465 F.2d 608, 613 (D.C. Cir. 1972); Gager v. “Bob Seidel?’, 300 F.2d 727, 731(D.C. Cir. 1962). The effect of this conversion is that, on appeal, this court may treat the matter as one involving a grant of summary judgment, regardless of the characterization by the District Court of its disposition of the matter, and may proceed to consider extra-pleading materials in determining whether summary judgment was appropriate. Id. I have, therefore, canvassed “[t]he record as a whole,” Gager, supra,300 F.2d at 731, in determining that no genuine issue of material fact exists as to the applicability of the act of state doctrine to this case, and that the District Court's dismissal should be affirmed.

The majority's position, Maj. Op. at 67-72, that the procedural posture of the case precludes invocation of the act of state doctrine is, in my view, a classic red herring. This argument begins with the majority bemoaning the fact that the doctrine “was not raised by any of the parties before the district court” and claiming that unfairness would be visited on plaintiffs by any consideration, at this stage, of Honduran acts of state. Second, the majority argues that the absence of “factual development” before the District Court disables this court from “findfing] the facts necessary to settle the controversy.” Id. at 67.

Neither branch of this argument will wash. As to the “procedural unfairness” claim, it is inconceivable that, given the location of the property at issue and the presence of Honduran troops, plaintiffs have not known from the outset that the act of state doctrine presents a serious barrier to their lawsuit Indeed, the consummate skill with which their complaint was drawn, artfully avoiding the role of the Honduran government, strongly evidences plaintiffs' clear understanding of this issue. Further, the original panel ordered the briefing of this issue, and plaintiffs have since responded both before the panel and the entire court en banc.Plaintiffs have clearly not been “ tak[en] ... by surprise,’ ” Maj. Op. at 69-70 (quoting Advisory Committee note to Rule 12), with respect to the importance of the act of state doctrine. For the majority now to say that consideration of the act of state here would constitute a “ [r] ush[] to judgment” “depriv- [ing] the plaintiff of a meaningful opportunity to present its case,” Maj. Op. at 71, verges on the whimsical. More fundamentally, for reasons discussed infra at 8-14,1 can imagine no “factual development” of this case by the plaintiffs whichstatements of the Honduran government's intention formally to expropriate that land, into something less than an act of state. That is, the majority's refusal to affirm dismissal of this case merely allows plaintiffs to go forward with their futile attempts to minimize and otherwise discredit the Honduran government's pivotal role in the creation of the RMTC.

3 “[J] udicial notice of a document evidencing an act of state” is a procedure sanctioned by the RESTATEMENT (REVISED) OF FOREIGN RELATIONS LAW § 428 comment g (“Form and proof of an act of state”) (Tent. Draft No. 4, 1983). It is clear that this court may take judicial notice for the firsttime of the contents of the Honduran government documents, as translated by the U.S. Department of State. See 21 C. Wright & K. Graham, FEDERAL PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE § 5110 at 527 (1977) (“The appellate court may, of course, take judicial notice on its own motion.”). Accord, Green v. Warden, U.S. Penitentiary, 699 F.2d 364, 369 (7th Cir.), cert. denied, 103 S.Ct 2436 (1983); State Fair of Texas v. U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission, 650 F.2d 1324, 1328 (5th Cir.), vacated as moot, 454 U.S. 1026 (1981); Bryant v. Carleson, 444 F.2d 353, 357 (9th Cir.), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 967 (1971).

Under the rule that a court may consider “matters of general public record” in disposing of a motion to dismiss, judicial notice of this document is proper even if my analysis of the procedural posture of this case, supra note 2, is rejected. Phillips v. Bureau of Prisons, 591 F.2d 966, 969 (D.C. Cir. 1979). See also District of Columbia v. Moxley, 471 F. Supp. 777, 779 (D.D.C. 1979). The State Department translation of the decree of the president of Honduras merits treatment as a matter of public record.

4 In Alfred DunhiU of London, Inc. v. Cuba, 425 U.S. 682, 695 (1976), the Supreme Court specifically mentioned “stat-uteLsJ, decree [s], order [s], or resolution [s] of a sovereign as establishing an act of state. (In Durihill, counsel for Cuba failed to offer any such evidence that “Cuba had repudiated its obligations in general or any class thereof or that it had as a sovereign matter determined to confiscate” the contested sums. Id.) Accord, Restatement (Revised), supranote 3, § 428 Reporters' Note 3 (“Act of state defined”).

5 See RESTATEMENT (REVISED), supra note 3, §428 comment g (act of state doctrine “possibly [applicable] to physical acts such as occupation of an estate by the state's armed forces in application of state policy”). The occupation in this case, in conjunction with the commencement of formal expropriation proceedings, clearly rises to the level of a sovereign act.

A governmental “taking” without prior formalities (or compensation) has a clear analogue in United States law. See Kirby Forest Indus., Inc. v. United States, 52 U.S.L.W. 4607, 4608 (U.S. May 22, 1984) :

[T]he United States is capable of acquiring privately owned land summarily, by physically entering into possession and ousting the owner. In such a case, the owner has a right to bring an “inverse condemnation” suit to recover the value of the land on the date of the intrusion by the Government. (Citations omitted).

It surely cannot seriously be maintained that Mr. Ramirez disputes the official involvement of Honduran governmental authorities. In addition to the declarations discussed previously in the text, appellants candidly admitted such Honduran involvement in their supplemental brief filed in this court on October 11,1983. Here is what appellants themselves say on the subject:

Defendants … are currently involved in operating and expanding the RMTC in colUtberaUon with the Honduran Armed Forces.

Reprinted in Appellants' Brief En Banc, Appendix B, at 4 (emphasis added). See also id. at 8, n.2: “plaintiffs' view [is] that the RMTC is primarily an activity of the United states not Honduras.” (“Emphasis added.)

6 Tentative Draft No. 3 of the RESTATEMENT (REVISED) OF FOREIGN RELATIONS LAW (1982) similarly adopts a functional analysis of “takings” of alien property, rather than focusing on the formalities followed by the foreign government. See id. §§ 711-712.

The majority's attempt to deal with this analysis, Maj. Op. at 66 n.154, is, in a word, misleading. Section 43 of the RESTATEMENT (SECOND), supra, on which the majority relies, deals only with actions of a foreign state “with respect to a tiling located, or an interest localized, outside of its territory.” It thus has no applicability whatever to this case.

7 case law makes clear that a taking of property, in eluding a “wrongful taking,” constitutes an act of state. In deed, the development of the doctrine from Sabbatino to the present day has largely been the result of litigation over Cuban nationalizations of alien property for which no compensation was ever paid. The nationalization decree at issue in Sabbatino contained provisions for compensation which were described by the Second Circuit as “illusory” and “little more than a travesty.” Banco National de Cuba v. Sabbatino,307 F.2d 845, 862 (2d Cir. 1962). The seizure of foreign banking assets, which eventually led to the Supreme Court's decision in First National City Bank v. Banco National de Cuba,406 U.S. 759 (1972), contained compensation procedures which the federal district court deemed “fictitious.” 270 F.Supp. 1004, 1010 (S.D.N.Y. 1967). Accord, Banco National de Cuba v. Chase Manhattan Bank, 658 F.2d 875, 878 (2d Cir. 1981) (parties to related litigation stipulated that no compensatory payments were ever made), rev'd on other grounds sub nom. First National City Bank v. Banco Para El Comertio Exterior de Cuba, 103 S.Ct. 2591 (1983). Finally, the seizure of cigar manufacturing assets which led to the decision in Dunhill, supra, was described by the district court in language directly relevant to the case at bar:

The [seizures], in practical effect, were complete confiscations. The owners were ousted without their consent from all properties and excluded from any participation in the businesses. Their rights to any receipts or profits were eliminated and no compensation was provided.

Menendez v. Faber, Coe & Gregg, Inc., 345 F.Supp. 527, 532 (S.D.N.Y. 1972).

8 The cases cited by the majority for the proposition that the United States not be allowed to use the doctrine to shield improper collaboration with foreign governments, Maj. Op. at 80-82 nn.183-85, do not contain relevant discussions of the act of state doctrine and are in any event distinguishable on several grounds.

The only cases cited by the majority which addressed improper acts by United States officials abroad in conjunction with foreign officials are Berlin Democratic Club v. Rumsfeld,410 F. Supp. 144 (D.D.C. 1976), and United States v. Hensel,699 F.2d 18 (1st Cir. 1983). In relevant part, Berlin Democratic Club involved electronic surveillance of United States citizens in West Germany by agents of the West German government; Hensel involved the search of a marijuana-laden boat by Canadian policemen. The actions of the foreign agents in both cases were intertwined with actions of United States agents to the extent that the so-called “joint venture” doctrine was implicated. This doctrine has been invoked in the past to challenge illegal searches and other violations of civil liberties by foreign officials, acting on the requests of United States officials. Before explaining why the doctrine seems to me inapplicable to the present action, I note that the decisions relied on by tiie majority do not represent the breaking of any new ground in the “joint venture” doctrine directly applicable to the present case.

It is also noteworthy that neither Berlin Democratic Clubnor Hensel contain any analysis of the act of state doctrine. This seems to me consistent with the different factual situations presented by the typical “joint venture” case—an illegal search or other infringement of civil liberties—and the facts of the Honduran seizure of plaintiffs' ranch. In the first place, thia case clearly involves foreign relations considerations of a vastly more important dimension than did the cases cited by the majority. Secondly, Honduras' seizure of land within its borders, even if, as the majority argues, it is beneficially owned by an American citizen, is an act specifically permitted under international law, provided reasonable compensation procedures are followed. Similarly, if this seizure had been committed within the United States by agents of the United States government, it is clear, abstracting from the standing questions ably discussed by Judge Scalia, that plaintiffs would be entitled to bring an inverse condemnation action, but no more. In other words, the fact that this action deals with rights to land in a foreign country, seized by that country's government, rather than with the protection of core civil liberties implicated in the cases cited by the majority, renders the “joint venture” analysis urged by the majority singularly inapplicable.

9 In its parade of horribles the majority also overlooks the President's authority to waive application of the First Hicken-looper Amendment's sanctions. See 22 U.S.C. § 2370(e)(1) (1982).

The majority is likewise off base in arguing that the expropriation decree issued by Honduras' Chief Executive is irrelevant to the issue of legality vel non under the First Hickenlooper Amendment. To the contrary, the very act of issuing the decree evidences an act of state solemnly undertaken by the Honduran government and at the same time the undisputed terms of that decree evidence that govemmenfs undertaking the appropriate steps to effect compensation. It is the taking of such steps aimed at speedy compensation that is required under the express terms of the First Hickenlooper Amendment 22 U.S.C. § 2370(e) (1). See also the discussion infra at p. 17. The majority errs in suggesting otherwise.