No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

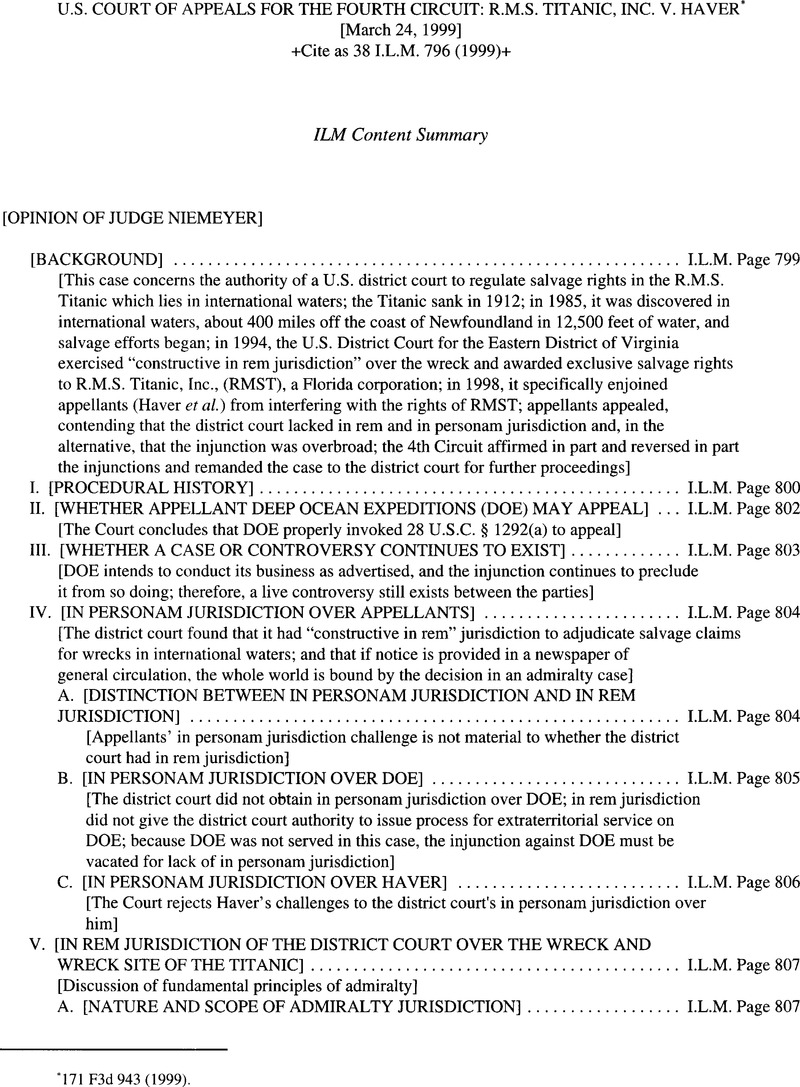

* 171 F3d 943 (1999).

1 RMST's invocation of “quasi in rem” jurisdiction appears to be misplaced. Quasi in rem jurisdiction is invoked as an interim step to obtain in personam jurisdiction. See Shaffer v. Heitner, 433 U.S. 186, 196 (1977). To be sure, in Shaffer, the Court stated that in a quasi in rem action, the “only role played by the property is to provide a basis for bringing the defendant into court.” Id. at 209. Articulating the role of quasi in rem jurisdiction, the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure state that when a complaint names a defendant who cannot be found within the district, property of the defendant within the district may be seized either to compel the defendant's appearance or to give effect to the relief requested in the complaint. See Fed. R. Civ. P. Supp. R. E(4). This case has little to do with quasi in rem jurisdiction because the wreck of the Titanic lies outside the district court's territorial jurisdiction. The proper inquiry here is whether a court in admiralty can award salvage rights in a shipwreck outside of United States’ territorial waters.

2 Although the United States signed the United Nations Convention in 1994, the Senate has not yet provided the necessary advice and consent for ratification.

3 Under the 1982 United Nations Convention, an exclusive economic zone is recognized, beginning at the outer limit of the territorial waters and extending to 200 nautical miles from the nation's shoreline. Within this economic zone, a nation may exercise exclusive control over economic matters involving fishing, the seabed, and the subsoil, but not over navigation. See United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Dec. 10, 1982, 21 I.L.M. 1245, 1280, arts. 56(1), 57. Even though the United States has not yet ratified this treaty, see supra note 2, it generally recognizes this 200-mile economic zone. See Schoenbaum, Thomas J., 1 Admiralty and Maritime Law, §2-16, at 35 (2d ed. 1994)Google Scholar (collecting legislation enacted by Congress in accordance with the Law of the Sea Convention).

4 In reaching this conclusion, we reject Haver's argument that the R.M.S. Titanic Maritime Memorial Act of 1986, 16 U.S.C. § 450rr et seq., precluded the district court from exercising jurisdiction over the wreck of the Titanic. That statute, while recognizing the “major national and international cultural and historical significance” of the Titanic, 16 U.S.C. § 450rr(a)(3), merely exists to encourage the United States (or more specifically, the President) to coordinate cooperative international efforts “for conducting research on, exploration of, and if appropriate, salvage of the R.M.S. Titanic.” 16 U.S.C. § 450rr(b)(3). The statute also specifically expresses Congress’ sense that “research and limited exploration activities concerning the R.M.S. Titanic should continue for the purpose of enhancing public knowledge of its scientific, cultural, and historical significance” pending the consummation of such international efforts. 16 U.S.C. § 450rr-5. We also refuse to construe the language in § 450rr-6 of the statute — “By enactment of sections 450rr to 450rr-6 of this title, the United States does not assert sovereignty, or sovereign or exclusive rights or jurisdiction over, or the ownership of, any marine areas or the R.M.S. Titanic” — as stripping the federal courts of jurisdiction over the wreck for purposes of recognizing, consistent withthe jus gentium,Rmst as the wreck's exclusive salvor. Read in the context of the entire R.M.S. Titanic Memorial Act, we believe that language has no bearing in this appeal.

5 For instance, even under American copyright law, where an architect has a copyright in the design of a building, that right does not extend to prevent the viewing and photographing of the building, if it is located at a public site or is visible from a public place. See 17 U.S.C. §120(a).