No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

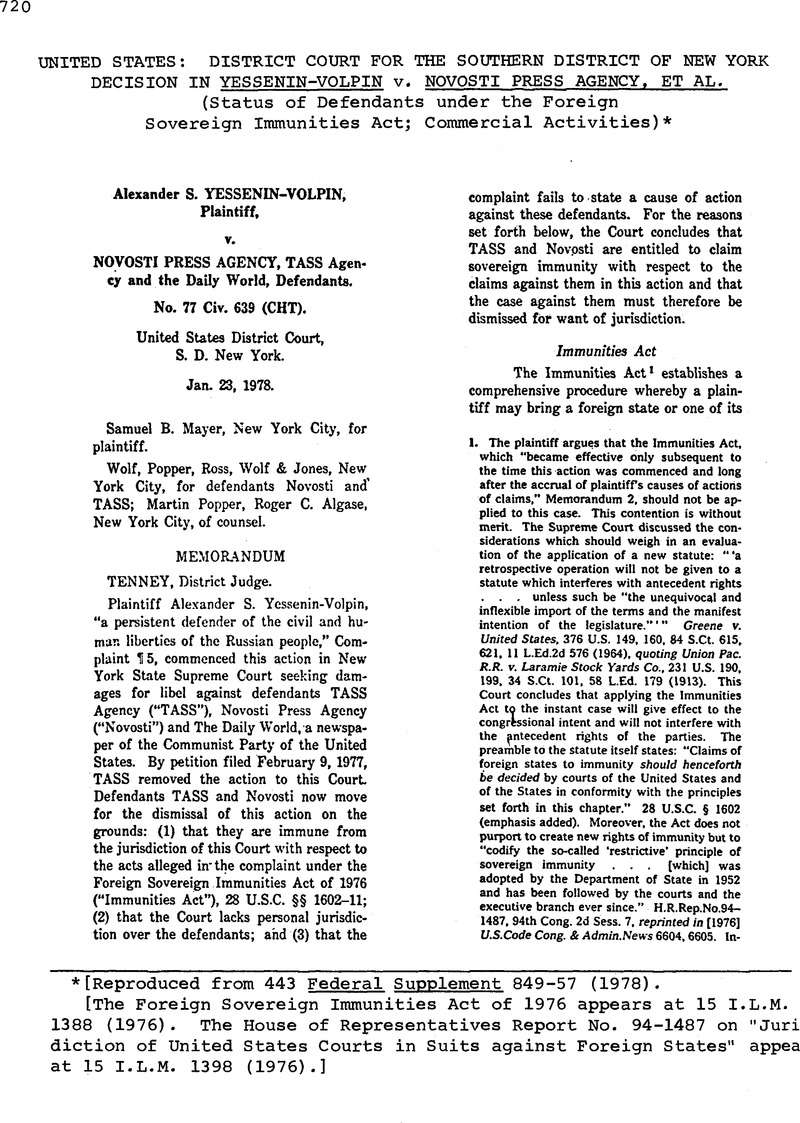

United States: District Court for the Southern District of New York Decision in Yessenin-Volpin v. Novosti Press Agency, et al. (Status of Defendants under the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act; Commercial Activities)

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 March 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Legislation and Regulations

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1978

References

* [Reproduced from the text provided by the U.S. Supreme Court.

[Other documents in this issue that relate to tanker safety and pollution prevention appear at page 541.]

1 Puget Sound is an estuary consisting of 2,500 square miles of inlets, s, and channels in the northwestern part of Washington. M'ore than islands are located within the Sound, and numerous marshes, tidal flats, lands, and beaches are found along the 2,000 miles of shoreline. Theid's waters and shorelines provide recreational, scientific, and educaal opportunities, as well as navigational and commercial uses, forhington citizens and others. The Sound, which is connected to the fie Ocean by the Strait of Juan de Fuca, is constantly navigated bymercial and recreational vessels and is a water resource of great value M State, as well as tcrthe United States.

2 We were informed during oral argument by the Attorney General of Washington that the pipeline from Canada to Cherry Point is no longer in service. Tr. of Oral Arg., 6.

3 The term “deadweight tons” is defined for purposes of the Tanker Law as the cargo-carrying capacity of a vessel, including necessary fuel oils,stores, and potable waters, as expressed in long tons (2,240 pounds per long ton).

4 Four environmental groups—Coalition Against Oil Pollution, National Wildlife Federation, Sierra Club, and Environmental Defense Fund, Inc.— “ and the prosecuting attorney for King County, Wash., intervened as defendants.

5 The United States has since modified its views and no longer contends that the Tanker Law is in all respects pre-empted by federal law.

6 The state defendants challenged the District Court's jurisdiction over them, asserting sovereign immunity under the Eleventh Amendment. They recognized that inEx parte Young, 209 U. S. 123 (1908), the Court held that the Eleventh Amendment does not bar suit in federal court against a state official for the purpose of obtaining an injunction against his enforcementof a state law alleged to be unconstitutional, but urged the District Court to overrule that decision or to restrict its application. The District Court declined to doBO. The request is repeated here, and we reject it.

7 Enrolled vessels are those “engaged in domestic or coastwide trade used for fishing,” whereas registered vessels are those engaged in trade w foreign countries.Douglas v.Seacoast Products, Inc., 431 U. S. 265, 2?273 (1977).

8 Included within the definition of steam vessels are “[a]U vessi regardless of tonnage size, or manner of propulsion, and whether se propelled or not, and whether carrying freight or passengers for hire not, … that shall have on board liquid cargo in bulk which is (A) inflammable or combustible, or (B) oil, of any kind or in a form, … or (C) designated as a hazardous polluting substance … 46 U. S. C. § 391a (2) (1970 ed., Supp. V).

9 The Senate Report compares Title I to “providing safer surface highs and traffic controls for automobiles,” while Title II is likened to >viding safer automobiles to transit those highways.” S. Rep. No. ‘24,92d Cong., 2d Sess., 9-10 (1972) (Senate Report). The Coast Guard is located in the Department of Transportation, s references to the “Secretary” are to the Secretary of that Department

11 The Secretary's current safety regulations with respect to the design and equipment of tank vessels appear at 46 CFR Parts 30-40 (1976). Section 31.05-1 of the regulations provides for the issuance of certificates of inspection to covered vessels complying with the applicable law and regulations and for endorsement thereon showing approval for the carriage of the particular cargoes specified. The regulation provides that “such endorsement shall serve as a permit for such vessel to operate.”

12 As directed by Title II, the Secretary, through his delegate, the Coast Guard, see 49 CFR § 1.46 (n)(4) (1976), has issued rules and regulations for protection of the marine environment relating to United States tank vessels carrying oil in domestic trade. 33 CFR Part 157 (1976). These regulations were initially designed to conform to the standards specified ina 1973 international convention, but have since been supplemented by additional requirements for new vessels going beyond the convention. 41 Fed. Reg. 54177 (1976). They have also been extended to vessels in the foreign trade, including foreign flag vessels.Ibid. It appears that the Coast Guard is now engaged in a rulemaking proceeding which looks toward the imposition of still more stringent design and construction standards. 42 Fed. Reg. 24868 (1977).

13 Title II in relevant part, 46 U. S. C. §391a (7)(A) (1970 ed., Supp. V), provides: “Such rules and regulations shall, to the extent possible, include but not be limited to standards to improve vessel maneuvering and stopping ability and otherwise reduce the possibility of collision, grounding, or other accident, … and to reduce damage to the marine environment by normal vessel operations such as ballasting and deballasting, cargo handling, and other activities.”

14 It should also be noted that the Secretary has authority under Title II to insure that adequately trained personnel are in charge of tankers. He is authorized to certify “tanker men” and to state the kinds of cargo that the holder of such certificate is, in the judgment of the Secretary, qualified to handle aboard vessels with safety. 46 U. S. C. § 391a (9) (1970 ed., Supp. V).

15 The Court has previously observed that ship design and construct standards are matters for national attention. InKelly v.WaskingU 302 U. S. 1 (1937), in the course of upholding state inspection of t particular vessels there involved, the Court stated that the state lawn “a comprehensive code” and that “it has provisions which may be deemed to fall within the class of reguitions which Congress alone can provide. For example, ‘Congress m establish standards and designs for the structure and equipment of vesse and may prescribe rules for their operation, which could not properly left to the diverse action of the States. The State of Washington mig prescribe standards, designs, equipment and rules of one sort, Oreg another, California another, and so on.”Id., at 14-15. Here, Congress has taken unto itself the matter of tanker design standan “and the Tanker Law's design provisions are unenforceable.

16 Elsewhere in the Senate Report it is stated: “The committee fui concurs that multilateral action with respect to comprehensive standar for the design, construction, maintenance and operation of tankers for t protection of the marine environment would be far preferable to unilata imposition of standards.” Senate Report, at 23.

17 The Senate Report notes that eliminating foreign vessels from Titles would be “ineffective, and possibly self-defeating,” because approximate 85% of the vessels in the navigable waters of the United States are gn registry.Id., at 22. The Report adds that making the Secretary's lotions applicable only to American ships would put them at a competdisadvantage with foreign flag ships.Ibid.The Department of State and the’ Department of Transportation, as as 12 foreign nations, expressed concern about Title II's authorization ie unilateral imposition of design standards on foreign vessels.Id., t.

19 We are unconvinced that because Title II speaks of the establishment >mprehensive “minimum standards”Florida Lime & Avocado Growers, v.Paul, 373 U. S. 132 (1963), requires recognition of state authoritynpose higher standards than the Secretary has prescribed. In that we sustained the state regulation against claims of pre-emption, but lid not rely solely on the statutory reference to “minimum standards” idicate that it furnished a litmus-paper test for resolving issues of anption. Indeed, there were other provisions in the Federal Act in tion that “militate[d] even more strongly against federal displacement ;he] state regulations.”Id., at 148. Furthermore, the federal regulai claimed to pre-empt state law were drafted and administered by local aizations and were “designed to do no more than promote orderlypetition among the South Florida [avocado] growers.”Id., at 151. i it is sufficiently clear that Congress directed the promulgation of lards on the national level, as well as national enforcement, with sis having design characteristics satisfying federal law being privileged rry tank-vessel cargoes in United States waters.

20 From 1950 until the PWSA was enacted, the Coast Guard carried out its port safety program pursuant to a delegation from the President of his authority under the Magnuson Act, 50 U. S. C. § 191. That Act based the President's authority to promulgate rules governing the operation and inspection of vessels upon his determination that the country's national security was ndangered. H. R. Rep. No. 92-563, 92d Cong., 1st Sess., 2 (1971) (House Report). The House Committee that considered Title I of the PWSA intended it to broaden the Coast Guard's authority to establish rules for port safety and protection of the environment. The Committee “The enactment of H. R. 8140 would serve an important dual purpose. First, it would bolster the Coast Guard's authority and capability to handle adequately the serious problems of marine safety and water pollution that confront us today. Second, it would remedy the long-standing problem concerning the statutory basis for the Coast Guard's port safety program.”Ibid.

21 Local Coast Guard authorities have published an operating manual containing the vessel traffic system for Puget Sound and explanatorymaterials. App. 155.

22 The advance notice of proposed rulemaking states that “[t]he Coast Guard is considering amending Part 164 of Title 33, Code of FederalRegulations to require minimum standards for tug assistance for vessels operating in confined waters to reduce the potential for collisions, rammings, and groundings in these areas.” 41 Fed. Reg. 18770 (1976). It statesthat the following factors will be considered in developing the rules: : of vessel, displacement, propulsion, availability of multiple screws or t (hrusters, controllability, type of cargo, availability of safety standards,; actual or predicted adverse weather conditions.Id., at 18771.

23 Appellees insist that the Secretary through Ins Coast Guard deleg; has already exercised his authority to require tugs in Puget Sound toextent he deems necessary and that the State should therefore not permitted to impose stricter provisions. Appellees submit letters or otevidence indicating that the local Coast Guard authorities have requi tug escorts for carriers of liquefied petroleum gas and on one occasionanother type of vessel. This evidence is not part of the record before but even accepting it, we cannot say that federal authorities have setupon whether and'in what circumstances tug escort for oil tankere Puget Sound should be required. The entire subject of tug escortsbeen placed on the Secretary's agenda, seemingly for definitive action, the notice of proposed rulemaking referred to in the text.

24 In fact, at the time of trial all tankers entering Puget SoundI required to have a tug escort, for no tanker then afloat had all ofdesign features required by the Tanker Law. App. 66.

25 We do not agree with appellees' assertion that the tug escort prsion, which is an alternative to the design requirements of the Tanker 1will exert pressure on tanker owners to comply with the design standi and hence is an indirect method of achieving what they submit is beystate power under Title II. The cost of tug escorts for all of app Arco's tankers in Puget Sound is estimated at $277,500 per year. Wnot a negligible amount, it is only a fraction of the estimated cos! outfitting a single tanker with the safety features required by § 88.16(2). The Office of Technology Assessment of Congress has estimated I constructing a new tanker with a double bottom and twin screws, justof the required features, would add roughly S8.8 million to the cost I 150,000 DWT tanker. Thus, contrary to the appellees' contention, ivery doubtful that the provision will pressure tanker operators into c plying with the design standards specified in §88.16.190(2). Whiletug provision may be viewed as a penalty for noncompliance with State's design requirements, it does not “stand as an obstacle to the aceplishment and execution of the full purposes and objectives of CongnHines v.Davidowitz, 312 U. S., at 67. The overall effect of § 88.16.190is to require tankers of over 40,000 DWT to have a tug escort while t navigate Puget Sound, a result in no way inconsistent with the P\!as it is currently being implemented.

26 It appears that the minimum water depth in Rosario Strait is 60 feet, p. 65, which according to the design standards used by the United States the 1973 International Conference on Marine Pollution would accomdate vessels well in ex-cess of 120,000 DWT. App.80.

27 During the hearings in the House, for example, Representative Keith expressed concern that States might on their own enact regulations restricting the size of vessels, noting that Delaware had already done so. He stated that “[w]e do not want the States to resort to individual actions that adversely affect our national interest.” Hearings on H. R. 867, H. R. 3635, H. R. 8140 before the Subcommittee on Coast Guard, Coast and Geodetic Survey, and Navigation of the House Committee on Merchant Marine and Fisheries, 92d Cong., 1st Sess., 30 (1971). The Commandant of the Coast Guard, Admiral Bender, responded that the Coast Guard “believefs] it is preferable for the approach to the problem of the giant tankers in particular to be resolved on an international basis.”Ibid. A representative of the Sierra Club testified before the Senate committee considering the PWSA and suggested the advisabilityol regulations limiting the size of vessels. Hearings on S. 2074 before the Senate Committee on Commerce, 92d Cong., 1st Sess., 77 (1971). In response to this suggestion, Senator Inouye questioned whether the necessary result of such a regulation would not be an increase in the number of tankers, so as to meet the Nation's requirements for oil. The Sierra Club witness acknowledged that there was “some controversy even among the oil company people as towhich would be the most hazardous, more smaller ships or fewer bigger ships.”Id., at 81. This statement is consistent with the stipulation of facts, App. 84, which states that: “Experts differ and there is good faith dispute as to whether the movementof oil by a smaller number of tankers in excess of 125,000 DWT in Puget Sound poses an increased risk of oil spillage compared to the risk from movement of a similar amount of oil by a larger number of smaller tankers in Puget Sound.”

28 We find no support for the appellants' position in the other federal environmental legislation they cite,i. e., the Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972, 86 Stat. 816, 33 U. S. C. § 1251et seq. (1970 ed., Supp. V); the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, 86 Stat. 1280, 16 U. S. C. § 1451et seq. (1970 ed., Supp. V); and the Deepwater Port Act of 1974, 88 Stat. 2126, 33 U. S. C. § 1501et seq. (1970 ed., Supp. V). While those statutes contemplate cooperative state-federal regulatory efforts, they expressly state that intent, in contrast to the PWSA. Furthermore, none of them concerns the regulation of the design or size of oil tankers, an area in which there is a compelling need foruniformity of decisionmaking.Appellees and the United States asamicus curiae urge that the Tanker Law's size limit also conflicts with the policy of the Merchant Marine Act of 1936, 49 Stat. 1985, as amended, 46 U. S. C. § 1101et seq., and thetanker construction program established thereunder by the Maritime Administration in implementation of its duty under the Act to develop anadequate and well-balanced merchant fleet. Under this program the construction of tankers of various sizes is subsidized, including tankers farin excess of 125,000 DWT. The Maritime Administration has rejected suggestions that no subsidies be offered for the building of the largertankers. There is some force to the argument, but we need not rely on it.

29 Although the District Court did not reach these additional grounds, the issues involved are legal questions, and the record seems sufficiently complete to warrant their resolution here without a remand to the District Court.

1 According to the record, no tanker currently afloat has all the design ures prescribed by the Tanker Law. Neither Atlantic Richfield nor train has plans to modify any tankers currently in operation to satisfy design standards, “because such retrofit is not economically feasible ler current and anticipated market conditions.” App. 67. Moreover, vessels being constructed by Seatrain will not meet the majority of the ign requirements, and, as the Court convincingly demonstrates,ante, 19-20, n. 24, the Tanker Law is not likely to induce tanker owners to irporate the specified design features into new tankers.

2 The relevant provision of Title I provides: In order to prevent damage to, or the destruction or loss of any vessel, ige, or other structure on or in the navigable waters of the United tea, or any land structure or shore area immediately adjacent to those era; and to protect the navigable waters and the resources therein from ironmental harms resulting from vessel or structure damage, destrucl, or loss, the Secretary of the department in which the Coast Guard is rating may—

(3) control vessel traffic in areas which he determines to be especially ardous, or under conditions of reduced visibility, adverse weather, vessel gestion, or other hazardous circumstances by— ‘(iii) establishing vessel size and speed limitations and vessel operating iditions … . ‘ * 33 U. S. C. § 1221 (3) (iii) (1970 ed., Supp. V). 3 The Rosario Strait “size limitation” is not contained in any written rule or regulation, and the record does not indicate how it came into existence. The only reference in the record is the following statement in the stipulation of facts: “The Coast Guard prohibits the passage of more than one 70,000 DWT vessel through Rosario Strait in either direction at any given time. During periods of bad weather, the size limitation is reduced to approximately 40,000 DWT.” App. 65. The Puget Sound Vessel Traffic System, 33 CFR Part 161, Subpart B (1976),as amended, 42 Fed. Reg. 29480 (1977), does not contain any size limitation, and the necessity for such a limitation apparently was never considered during the rulemaking process. See 38 Fed. Reg. 21228 (1973) (notice of proposed rulemaking); 39 Fed. Reg. 25430 (1974) (summary of comments received during rulemaking).

4 Title I provides in relevant part: “In determining the need for, and the substance of, any rule or regulation or the exercise of other authority hereunder the Secretary shall, p&iong other things, consider'— “(6) existing vessel traffic control systems, services, and schemes; and “(7) local practices and customs … .” 33 U. S. C. § 1222 (e) (1970 ed., Supp. V).

5 The stipulation of facts does not specify when the size rule for Rosario Strait was established. The rule apparently was in force at the time the stipulation was entered, see n. 3,supra, but the Tanker Law had gone into . effect prior to that time.

6 The Tanker Law contains the following statement of intent and purpose: “Because of the danger of spills, the legislature finds that the transportation of crude oil and refined petroleum products by tankers on Puget Sound and adjacent waters creates a great potential hazard to important natural resources of the state .and to jobs and incomes dependent on these resources. “The legislature also recognizes Puget Sound and adjacent waters are a relatively confined salt water environment with irregular shorelines and therefore there is a greater than usual likelihood of long-term damage from any large oil spill. “The legislature further recognizes that certain areas of Puget Sound and adjacent waters have limited space for maneuvering a large oil tanker and that these waters contain many natural navigational obstacles as well as a high density of commercial and pleasure boat traffic.” Wash. Rev. Code § 88.16.170 (Supp. 1975). The natural navigational hazards in the Sound are compounded by fog, tidal currents, and wind conditions, in addition to the high density of vehicle traffic. App. 69. Among the “areas … [with] limited space for maneuvering a large oil tanker,” referred to by the Washington Legislature, is undoubtedly RosarioStrait. The Strait is less than one-half mile wide at its narrowest point, Exh. G, and portions of the shipping route through the Strait have a depth of only 60 feet, App. 65. (A 190,000 DWT tanker has a draft of approximately 61 feet, and a 120,000 DWT tanker has a draft of approximately 52 feet.Id., at 80.)

7 In addition to finding the Tanker Law's size limit to be inconsistent with the PWSA and federal actions thereunder, the Court suggests that “[t]here is some force to the argument” that the size limit conflicts with the tanker construction program established by the Maritime Administration pursuant to the Merchant Marine Act of 1936.Ante, at 25 n. 27. The Court does not rely on this argument, however, and it is totally lacking in factual basis. While it is true that construction of tankers larger than 125,000 DWT has been subsidized under the program, almost two-thirds of the tankers that have been or are being constructed have been smaller than 125,000 DWT, App. 60; of the remainder, the smallest are 225,000 DWT vessels with drafts well in excess of 60 feet—too large to pass through Rosario Strait, see n. 6,supra, or dock at any of the refineries on Puget Sound (Atlantic Richfield's refinery at Cherry Point Me a dockside depth of 55 feet; none of the other five refineries on Puget Soundhas sufficient dockside depth even to accommodate tankers as large} 125,000 DWT. App. 47-48,80.). ] Appellees advance one final argument for invalidating the 125,000 Dfi) size limit under the Supremacy Clause. Relying on the well-establistit proposition that federal enrollment and licensing of a vessel give*: authority to engage in coastwise trade and to navigate in state watt*Douglas v.Seacoast Products, Inc., 431 U. S. 265, 276, 280-281 (1977JGibbons -v.Ogden, 9 Wheat. 1, 212-214 (1824), appellees asserttk Washington may not exclude from any of its waters tankers that ha| been enrolled and licensed, or registered, pursuant to the federal vess registration, enrollment, and licensing laws, 46 U. S. C. §§ 221, 251, 28 Even assuming that registration of a vessel carries with it the sail privileges as enrollment and licensing, this argument ignores a propositi! as well established as the one relied on by appellees: notwithstanding tl privileges conferred by the federal vessel license, “States may impose upj federal licensees reasonable, nondiscriminatory conservation and envinf mental protection measures otherwise within their police power.”Dowjk v.Seacoast Products, Inc., supra, at 277; see,e. g., Huron Portland CemelCo. v.Detroit, 362 U. S. 440 (1960);Manchester v.Massachusetts, lJ U. S. 240 (189^1);Smith v.Maryland, 18 How. 71 (1855). The TanlS Law's size limitation appears to be a reasonable environmental protects measure, see n. 8,infra, and it is imposed even-handedly againsthA residents and nonresidents of the State.

8 The stipulation quoted by the Court,ante, at 23 n: 26, mere! establishes that there is good-faith dispute as to whether exclusion of laij tankers will in fact reduce the risk of oil spillage in Puget Sound. | showing that there is conflicting evidence is not sufficient to undercut tl presumption that a State's police power has been exercised in a ratioi| manner. See,e. g., Brotherhood oj Locomotive Firemen & Enginemmi Chicago, R. I. & R. Co., 393 U. S. 129,138-139 (1968). 8 Exclusion of tankers larger than 125,000 DWT has not resulted in ai reduction in the amount of oil processed at the Puget Sound refinerij App. 68. Moreover, according to the record, use of a 120,000 D^f tanker rather than a 150,000 DWT tanker increases the cost of shippif oil from Valdez, Alaska to Cherry Point by a mere $.02 to $.04 per barnid., at 64; and the record does not specify the relevant cost data for d Persian Gulf-Cherry Point route. Finally, appellees offered no conal evidence of any significant disruption in their tanker operations, or of at decrease in the market value of the tankers that they own, as a result the Tank, r Law's provisions.

1 1 Wash. Rev. Code § 88.16.190 (2) reads as follows: (2) An oil tanker, whether enrolled or registered, of forty to one dred and twenty-five thousand deadweight tons may proceed beyond paints enumerated in subsection (1) if such tanker possesses all of the >wing standard safety features: (a) Shaft horsepower in the ratio of one horsepower to each two and half deadweight tons, and (b) Twin screws; and (c) Double bottoms, underneath all oil and liquid cargo compartments; (d) Two radars in working order and operating, one of which, must be son avoidance radar; and (e) Such other navigational position location systems as may be Bribed from time to time by the board of pilotage commissioners: IOVIDED, That, if such forty to one hundred and twenty-five thousand dweight ton tanker is in ballast or is under escort of a tug or tugs with aggregate shaft horsepower equivalent to five percent of the deadweight s of that tanker, subsection (2) of this' section shall not apply: 0VIDED FURTHER, That additional tug shaft horsepower equiva- :ies may be required under certain conditions as established by rule and illation of the Washington utilities and transportation commission suant to chapter 34.04 RCW: PROVIDED FURTHER, That a tanker ess than forty thousand deadweight tons is not subject to the provisions this act.”

2 At p. 19,ante, the Court seems to characterize the tug escort requirent as such a “general rule.”

3 The possibility of States' enacting legislation similar to Washington's is not remote. Alaska has enacted legislation requiring payment of a “risk charge” by vessels that do not conform to state design requirements, Alaska Stat. §30.20.010et seq. (Cum. Supp. 1976), and California is considering comparable legislation. See Brief of the State of California et al., asamici curiae, p. 3 n. 2.

4 No matter how small the cost in the individual case, the State's effort here to enforce its general determinations on vessel safety must be viewed as an “obstacle” to the attainment of Congress' objective of providing comprehensive standards for vessel design. SeeHines v.Davidovntz, 312 U. S. 52, 67. This does not mean that the State cannot adopt any general rules imposing tug escort requirements, but it does mean that it cannot condition those requirements on safety determinations that are pre-empted by federal law, thus “imposing] additional burdens not contemplated by Congress.”De Canas v.Bica, 424 U. S. 351, 358 n. 6.

5 The validity of Washington's tug escort provision may be short lived, despite today's opinion. The Secretary is now contemplating regulations in this area, and even the majority concedes that they may pre-empt the State's regulation.Ante, at 19. While this lessens the impact of the State's regulation and the threat it poses to the federal scheme, the legal issue is not affected by the imminence of agency action