No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 March 2017

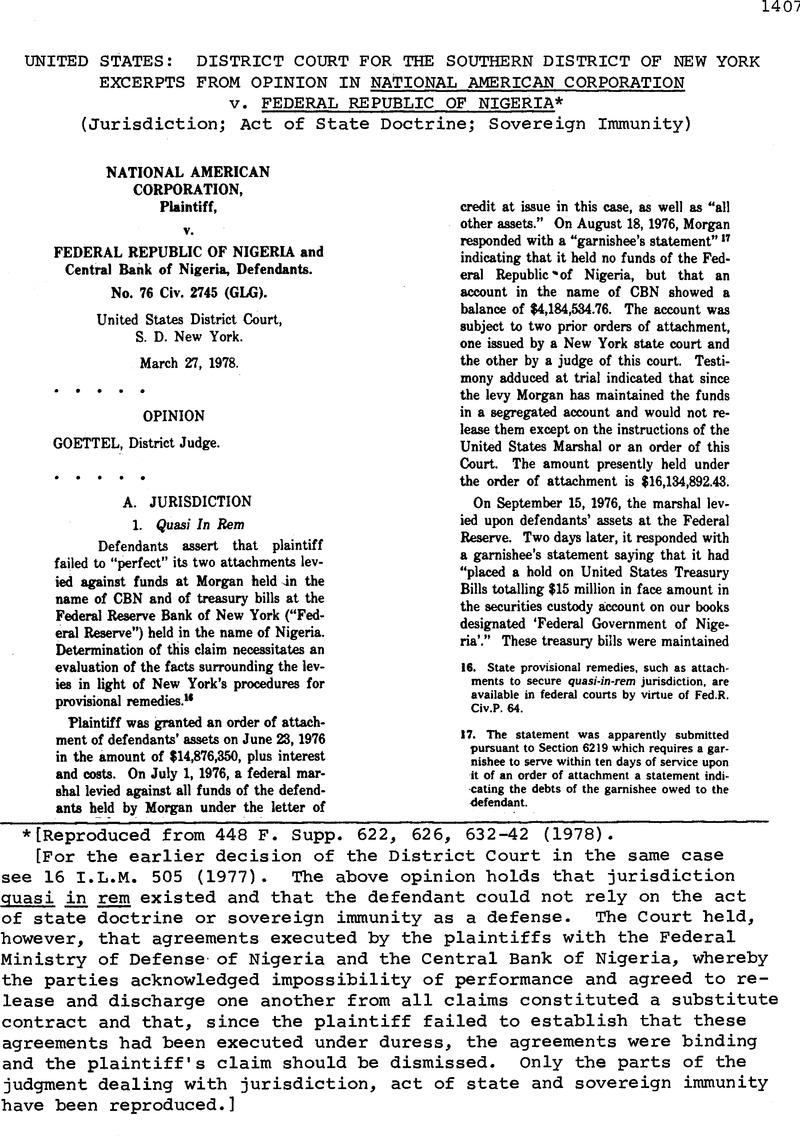

[Reproduced from 448 F. Supp. 622, 626, 632-42 (1978).

[For the earlier decision of the District Court in the same case see 16 I.L.M. 505 (1977). The above opinion holds that jurisdiction quasi in rem existed and that the defendant could not rely on the act of state doctrine or sovereign immunity as a defense. The Court held, however, that agreements executed by the plaintiffs with the Federal Ministry of Defense of Nigeria and the Central Bank of Nigeria, whereby the parties acknowledged impossibility of performance and agreed to release and discharge one another from all claims constituted a substitute contract and that, since the plaintiff failed to establish that these agreements had been executed under duress, the agreements were binding and the plaintiff's claim should be dismissed. Only the parts of the judgment dealing with jurisdiction, act of state and sovereign immunity have been reproduced.]

16 State provisional remedies, such as attachments to secure quasi-in-rem jurisdiction, are available in federal courts by virtue of Fed.R. Civ.P. 64.

17 The statement was apparently submitted pursuant to Section 6219 which requires a garnishee to serve within ten days of service upon it of an order of attachment a statement indicating the debts of the garnishee owed to the defendant.

18 N.Y.C.P.L.R. § 6215 provides an alternate procedure for levy “by seizure” which requires the sheriff to take into his custody property “capable of delivery” if the plaintiff indemnifies him.

19 A special proceeding is a New York procedural device which is distinguished from the standard civil action. N.Y.C.P.L.R. § 103(b) (McKinney 1972). The procedures used are similar to motion practice and the device is designed for speedy resolution of issues. Wachtell, New York Practice Under the CPLR 459 (5th ed. 1976).

20 This last factor represents a departure from prior New York practice. The old Civil Practice Act provision, Section 922(1) required the extension to be sought within the ninety day period. 7A Weinstein 6214.15 (1977).

One federal case, construing the procedures outlined in Section 6214 insisted upon strict compliance with the statute and stated incidentally that the motion for an extension of time must be made within ninety days of service of the attachment order. Worldwide Carriers, Ltd. v. Aris Steamship Co., 312 F.Supp. 172, 175 n.5. (S.D.N.Y.1970). The cases relied upon, however, were decided under the prior statute which, as mentioned above, explicitly required the motion to be made during that period. See, Corwin Consultants, Inc. v. Interpublic Group of Companies, Inc., 375 F.Supp. 186, 195 (S.D.N.Y.1974), reversed on other grounds, 512 F.2d 605 (2d Cir. 1975).

21 The Court first brought the holding in Shaffer v. Heitner to defendants’ attention in July, 1977 and requested that any objection under it be made promptly. After several informal reminders, the defendants still did nothing until galvanized by the November scheduling of a trial to commence in several weeks.

22 See footnote 31, infra.

23 The Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act of 1976, 28 U.S.C. § 1608(a)(3) (Supp.1977) permits service by mail upon the head of a foreign ministry in certain circumstances.

24 In Victory Transport v. Comisaria General, 336 F.2d 354 (2d Cir. 1964), cert. denied, 381 U.S. 93-4, 85 S.Ct. 1763, 14 L.Ed.2d 698 (1965), the Second Circuit implicitly held that the manner of service on a foreign state and its agencies was governed by Fed.R.Civ.P. 4. Because of the substantial similarity of the agencies sued in Petrol Shipping and Victory Transport, the variant results in these two cases cannot be reconciled and, therefore, the later decision in Petrol Shipping should be regarded as the Circuit’s position. 4 Wright & Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure § 1111 at 450-51 (1969).

25 In Arrowsmith, the issue was whether Congress, in enacting Fed.R.Civ.P. 4, intended to displace state standards of amenability in diversity actions by the federal standards developed in International Shoe Co. v. Washington, 326 U.S. 310, 66 S.Ct. 154, 90 L.Ed. 95 (1945), McGee v. International Life Insurance Co., 355 U.S. 220, 78 S.Ct. 199, 2 L.Ed.2d 223 (1957) and their progeny. The Second Circuit held that the potentially narrower state standard applied.

26 While plaintiff asserts that the Nigerian airline maintains offices here, this factor does not give jurisdiction over other entities of the government or the government itself. Vicente v. Trinidad, 53 A.D.2d 76, 385 N.Y.S.2d 83 (1st Dep’t 1976), aff’d 42 N.Y.2d 929, 397 N.Y.S.2d 1007, 366 N.E.2d 1361 (1977); see Petrol Shipping at 110.

27 The House Report which accompanied the Immunities Act specifically states that a central bank should be regarded as an agency or instrumentality of a foreign state. H.R.Rep. No. 94-1487, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 15-16 reprinted in [1976] U.S. Code Cong. & Admin. News at 6604 [hereinafter House Report].

28 The decrees are Government Notice No. 1434, dated August 9, 1975, entitled “Regulations on Sailing and Arrivals on Vessels” which required all shipping companies to give Nigeria two months advance notice of sailing and other information. Decree No. 40 of the Ports Emergency Provisions provides that after December 19, 1975, vessels must not enter the port unless official permission has been granted and imposes seemingly criminal penalties for disregard of the decree.

29 It was initially claimed that the retention of funds was a second act of state independent of the nationalization decree. It was not until reargument in the Supreme Court that the nationalized concerns asserted a more “typical” act of state theory. This was that the right to repudiate the debt was encompassed by the original decree nationalizing the businesses. Friedman, & Blau, , “Formulating A Commercial Exception to the Act of State Doctrine: Alfred Dunhill of London, Inc. v. Republic of Cuba ,” 50 St. John’s L.Rev. 666, 679-80 (1976)Google Scholar.

30 Traditionally, sovereign immunity raises a jurisdictional bar (technically, a relinquishment of jurisdiction previously acquired), while the act of state doctrine invokes choice-of-law concepts. Alfred Dunhill of London. Inc. v. Republic of Cuba, 425 U.S. at 705 n. 18, 96 S.Ct. at 1854. The latter, in the view of the Second Circuit, functions as an issue preclusion device. Hunt v. Mobil Oil, 550 F.2d 68 (2d Cir.), cert. denied, 434 U.S. 984, 98 S.Ct. 608, 54 L.Ed. 2d 477 (1977).

31 In Victory Transport v. Comisaria General, 336 F.2d 354 (2d Cir. 1964), cert. denied. 381 U.S. 934, 85 S.Ct. 1763, 14 L.Ed.2d 698 (1965), the Second Circuit adopted the restrictive theory of sovereign immunity which eliminates the defense on claims arising from the commercial acts (jure gestionis) as opposed to the governmental acts (jure imperii) of a sovereign. The decision followed in the wake of the State Department’s issuance of the well-known Tate letter adopting the restrictive theory as the official policy of the Executive Branch. 26 Dept. State Bull. 984 (1952). The process was completed by its codification in the Immunities Act. 28 U.S.C. § 1605(a)(2) (1977 Supp.); House Report at 7.