Article contents

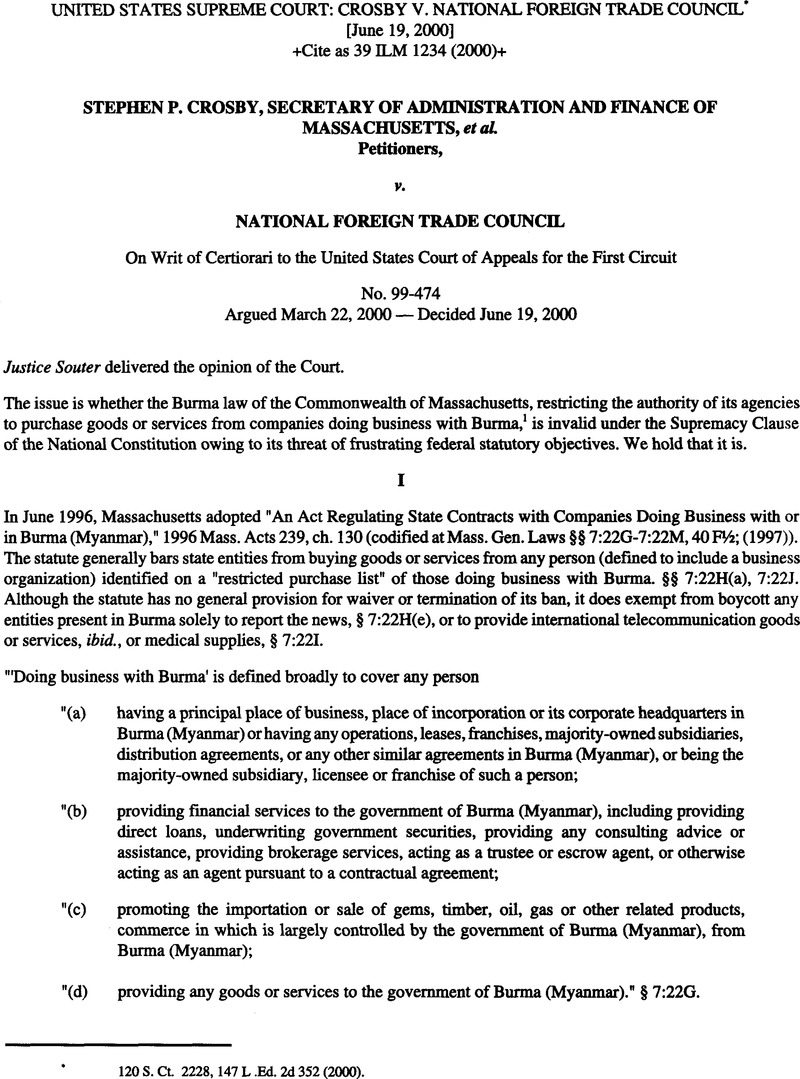

United States Supreme Court: Crosby v. National Foreign Trade Council*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 2000

Footnotes

120 S. Ct. 2228,147 L .Ed. 2d 352 (2000).

References

Endnotes

1 The Court of Appeals noted that the ruling military government of “Burma changed [the country's] name to Myanmar in 1989,” but the court then said it would use the name Burma since both parties and amici curiae, the state law, and the federal law all do so. National Foreign Trade Council v. Natsios, 181 F.3d 38,45, n. 1 (CA1 1999). We follow suit, noting that our use of this term, like the First Circuit's, is not intended to express any political view. See ibid.

2 According to the District Court, companies may challenge their inclusion on the list by submitting an affidavit stating that they do no business with Burma. National Foreign Trade Council v. Baker, 26 F. Supp. 2d 287, 289 (Mass. 1998). The Massachusetts Executive Office's Operational Services Division makes a final determination. Ibid.

3 The President also delegated authority to implement the policy to the Secretary of the Treasury, in consultation with the Secretary of State. § 6. On May 21, 1998, the Secretary of the Treasury issued federal regulations implementing the President's Executive Order. See 31 CFR pt. 537 (Burmese Sanctions Regulations).

4 One of the state offices changed incumbents twice during litigation before reaching this Court, see National Foreign Trade Council v. Natsios, 181 F.3d 38,48, n. 4 (CA1 1999), and once more after we granted certiorari.

5 “At least nineteen municipal governments have enacted analogous laws restricting purchases from companies that do business in Burma.” 181 F.3d,at 47; Pet. for Cert. 13 (citing N.Y.C. Admin. Code §6-115 (1999); Los Angeles Admin. Code, Art. 12, §§ 10.38 et seq.(1999); Philadelphia Code § 17-104(b) (1999); Vermont H. J. Res. 157 (1998); 1999 Vt. Laws No. 13).

6 We recognize, of course, that the categories of preemption are not “rigidly distinct.” English v. General Elec. Co., 496 U.S. 72,79, n. 5 (1990). Because a variety of state laws and regulations may conflict with a federal statute, whether because a private party cannot comply with both sets of provisions or because the objectives of the federal statute are frustrated, “field pre-emption may be understood as a species of conflict pre-emption.” id., at 79-80, n. 5; see also Gade v. National Solid Wastes Management Assn., 505 U.S. 88, 104, n. 2 (1992) (quoting English, supra); 505 U.S., at 115-116 (Souter, J., dissenting) (noting similarity between “purpose-conflict pre-emption” and pre-emption of a field, and citing L. Tribe, American Constitutional Law 486 (2d ed. 1988)); 1 L. Tribe, American Constitutional Law 1177 (3d ed. 2000) (noting that “field” preemption may fall into any of the categories of express, implied, or conflict preemption).

7 The State concedes, as it must, that in addressing the subject of the federal Act, Congress has the power to preempt the state statute. See Reply Brief for Petitioners 2; Tr. of Oral Arg. 5-6. We add that we have already rejected the argument that a State's “statutory scheme… escapes pre-emption because it is an exercise of the State's spending power rather than its regulatory power.” Wisconsin Dept. of Industry v. Gould Inc., 475 U.S. 282,287 (1986). In Gould, we found that a Wisconsin statute debarring repeat violators of the National Labor Relations Act, 29 U.S.C. § 151 et seq., from contracting with the State was preempted because the state statute's additional enforcement mechanism conflicted with the federal Act. Gould, 475 U.S., at 288-289. The fact that the State “ha[d] chosen to use its spending power rather than its police power” did not reduce the potential for conflict with the federal statute. Ibid.

8 We leave for another day a consideration in this context of a presumption against preemption.See United States v.Locke, 529U.S.—,—(2000) (slip op., at 16). Assuming,arguendo, that some presumption against preemption is appropriate, we conclude, based on our analysis below, that the state Act presents a sufficient obstacle to the full accomplishment of Congress's objectives under the federal Act to find it preempted.See Hines v.Davidowitz, 312 U.S. 52,67 (1941). Because our conclusion that the state Act conflicts with federal law is sufficient to affirm the judgment below, we decline to speak to field preemption as a separate issue,see n. 6, supra, or to pass on the First Circuit's rulings addressing the foreign affairs power or the dormant Foreign Commerce Clause.See Ashwander v.TVA, 297 U.S. 288, 346-347 (1936) (concurring opinion).

9 Statements by the sponsors of the federal Act underscore the statute's clarity in providing the President with flexibility in implementing its Burma sanctions policy. See 142 Cong. Rec. 19212 (1996) (emphasizing importance of providing “the administration flexibility in reacting to changes, both positive and negative, with respect to the behavior of the [Burmese regime]“) (statement of principal sponsor Sen. Cohen); id., at 19213; id., at 19221 (describing the federal act as “giv[ing] the President, who, whether Democrat or Republican, is charged with conducting our Nation's foreign policy, some flexibility“) (statement of cosponsor Sen. McCain); id., at 19220 (“We need to be able to have the flexibility to remove sanctions and provide support for Burma if it reaches a transition stage that is moving toward the restoration of democracy, which all of us support“) (statement of cosponsor Sen. Feinstein). These sponsors chose a pliant policy with the explicit support of the Executive. See, e.g., id., at 19219 (letter from Barbara Larkin, Assistant Secretary, Legislative Affairs, U.S. Department of State to Sen. Cohen) (admitted by unanimous consent) (“We believe the current and conditional sanctions which your language proposes are consistent with Administration policy. As we have stated on several occasions in the past, we need to maintain our flexibility to respond to events in Burma and to consult with Congress on appropriate responses to ongoing and future development there“).

10 The State makes arguments that could be read to suggest that Congress's objective of Presidential flexibility was limited to discretion solely over the sanctions in the federal Act, and that Congress implicitly left control over state sanctions to the State. Brief for Petitioners 19-24. We reject this cramped view of Congress's intent as against the weight of the evidence. Congress made no explicit statement of such limited objectives. More importantly, the federal Act itself strongly indicates the opposite. For example, under the federal Act, Congress explicitly identified protecting “national security interests” as a ground on which the President could suspend federal sanctions. § 57O(e), 110 Stat. 3009-167. We find it unlikely that Congress intended both to enable the President to protect national security by giving him the flexibility to suspend or terminate federal sanctions and simultaneously to allow Massachusetts to act at odds with the President's judgment of what national security requires.

11 These provisions strongly resemble the immediate sanctions on investment that appeared in the proposed section of H. R. 3540 that Congress rejected in favor of the federal act. See H. R. 3540,104th Cong., 2d Sess., § 569(1) (1996).

12 The sponsors of the federal Act obviously anticipated this analysis. See, e.g., 142 Cong. Rec. at 19220 (1996) (statement of Sen. Feinstein) (“We may be able to have the effect of nudging the SLORC toward an increased dialog with the democratic opposition. That is why we also allow the President to lift sanctions“).

13 The fact that Congress repeatedly considered and rejected targeting a broader range of conduct lends additional support to our view. Most importantly, the federal Act, as passed, replaced the original proposed section of H. R. 3540, which barred “any investment in Burma” by a United States national without exception or limitation. See H. R. 3540, 104th Cong., 2d Sess., § 569(1) (1996). Congress also rejected a competing amendment, S. 1511, 104th Cong., 1st Sess. (Dec. 29, 1995), which similarly provided that “United States nationals shall not make any investment in Burma,” § 4(b)(l), and would have permitted the President to impose conditional sanctions on the importation of “articles which are produced, manufactured, grown, or extracted in Burma,” § 4(c)(l), and would have barred all travel by United States nationals to Burma, § 4(c)(2). Congress had rejected an earlier amendment that would have prohibited all United States investment in Burma, subject to the President's power to lift sanctions. S. 1092,104th Cong., 1st Sess. (July 28,1995). Statements of the sponsors of the federal act also lend weight to the conclusions that the limits were deliberate. See, e.g., 142 Cong. Rec. 19279 (1996) (statement of Sen. Breaux) (characterizing the federal Act as “strik[ing] a balance between unilateral sanctions against Burma and unfettered United States investment in that country“). The scope of the exemptions was discussed, see ibid.(statements of Sens. Nickles and Cohen), and broader sanctions were rejected, see id, at 19212 (statement of Sen. Cohen); id., at 19280 (statement of Sen. Murkowski) (“Instead of the current draconian sanctions proposed in the legislation before us, we should adopt an approach that effectively secures our national interests“).

14 The State's reliance on CTS Corp. v. Dynamics Corp. of America, 481 U.S. 69, 82-83 (1987), for the proposition that “[w]here the state law furthers the purpose of the federal law, the Court should not find conflict” is misplaced. See Brief for Petitioners 21-22. In CTS Corp., we found that an Indiana state securities law “further[ed] the federal policy of investor protection,” 481 U.S., at 83, but we also examined whether the state law conflicted with federal law “[i]n implementing its goal,” ibid. Identity of ends does not end our analysis of preemption. See Gould, 475 U.S., at 286.

15 The record supports the conclusion that Congress considered the development of a multilateral sanctions strategy to be a central objective of the federal act. See, e.g., 142 Cong. Rec. 19212 (1996) (remarks of Sen. Cohen) (“[T]o be effective, American policy in Burma has to be coordinated with our Asian Mends and allies“); id., at 19219 (remarks of Sen. Feinstein) (“Only a multilateral approach is likely to be successful“).

16 Such concerns have been raised by the President's representatives in the Executive Branch. See Testimony of Under Secretary of State Eizenstat before the Trade Subcommittee of the House Ways and Means Committee (Oct 23, 1997) (hereinafter Eizenstat testimony), App. 116 (“[U]nless sanctions measures are well conceived and coordinated, so that the United States is speaking with one voice and consistent with our international obligations, such uncoordinated responses can put the US on the political defensive and shift attention away from the problem to the issue of sanctions themselves“). We have expressed similar concerns in our cases on foreign commerce and foreign relations. See, e.g., Japan Line, Ltd v. County of Los Angeles, 441 U.S. 434,449 (1979); Chy Lung v. Freeman, 92 U.S., at 279; cf. The Federalist No. 80, pp. 535-536 (J. Cooke ed. 1961) (A. Hamilton) (“[T]he peace of the whole ought not to be left at the disposal of a part. The union will undoubtedly be answerable to foreign powers for the conduct of its members“).

17 The record reflects that sponsors of the federal Act were well aware of this concern and provided flexibility to the President over sanctions for that very reason. See, e.g., 142 Cong. Rec. at 19214 (statement of Sen. Thomas) (“Although I will readily admit that our present relationship with Burma is not especially deep, the imposition of mandatory sanctions would certainly downgrade what little relationship we have. Moreover, it would affect our relations with many of our allies in Asia as we try to corral them into following our lead“); id., at 19219 (statement of Sen. Feinstein) (“It is absolutely essential that any pressure we seek to put on the Government of Burma be coordinated with the nations of Asean and our European and Asian allies. If we act unilaterally, we are more likely to have the opposite effect — alienating many of these allies, while having no real impact on the ground“).

18 In amicus briefs here and in the courts below, the EU has consistently taken the position that the state Act has created “an issue of serious concern in EU-U.S. relations.” Brief for European Communities et at. as Amici Curiae 6.

19 Although the WTO dispute proceedings were suspended at the request of Japan and the EU in light of the District Court's ruling below, Letter of Ole Lundby, Chairman of the Panel, to Ambassadors from the European Union, Japan, and the United States (Feb. 10,1999), and have since automatically lapsed, Understanding on Rules and Procedures Governing the Settlement of Disputes, 33 International Legal Materials 1125,1234 (1994), neither of those parties is barred from reinstating WTO procedures to challenge the state Act in the future. In fact, the EU, as amicus before us, specifically represents that it intends to begin new WTO proceedings should the current injunction on the law be lifted. Brief for European Communities et al. as Amici Curiae 7. We express no opinion on the merits of these proceedings.

20 Senior Level Group Report to the U.S.-EU Summit, Washington 3 (Dec. 17,1999), http://www.eurunion.org/news/summit/Summit Annex/SLGRept.html.

21 Assistant Secretary Larson also declared that the state law “has hindered our ability to speak with one voice on the grave human rights situation in Burma, become a significant irritant in our relations with the EU and impeded our efforts to build a strong multilateral coalition on Burma where we, Massachusetts and the EU share a common goal.” Assistant Secretary of State Alan P. Larson, State and Local Sanctions: Remarks to the Council of State Governments 3 (Dec. 8,1998).

22 The United States, in its brief as amicus curiae, continues to advance this position before us. See Brief for United States as Amicus Curiae, 8-9, and n. 7, 34-35. This conclusion has been consistently presented by senior United States officials. See also Testimony of Deputy Assistant Secretary of State David Marchick before the California State Assembly, Oct. 28,1997, App. 137; Testimony of Deputy Assistant Secretary of State David Marchick before the Maryland House of Delegates Committee on Commerce and Government Matters, Mar. 25,1998, id., at 166 (same).

23 We find support for this conclusion in the statements of the congressional sponsors of the federal Act, who indicated their opinion that inflexible unilateral action would be likely to cause difficulties in our relations with our allies and in crafting an effective policy toward Burma. See n. 17, supra. Moreover, the facts that the Executive specifically called for flexibility prior to the passage of the federal Act, and that the Congress rejected less flexible alternatives and adopted the current law in response to the Executive's communications, bolster the relevance of the Executive's opinion with regard to its ability to accomplish Congress's goals. See n. 9, supra.

24 State appears to argue that we should ignore the evidence of the WTO dispute because under the federal law implementing the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), Congress foreclosed suits by private persons and foreign governments challenging a state law on the basis of GATT in federal or state courts, allowing only the National Government to raise such a challenge. See Uruguay Round Agreements Act (URRA), § 102(c)(l), 108 Stat 4818,19 U.S. C. §§ 3512(b)(2)(A), 3512(c)(l); see also “ Statement of Administrative Action” (SAA), reprinted in H. R. Doc. No. 103-216, pp. 656,675-677 (1994). To consider such evidence, in their view, would effectively violate the ban by allowing private parties and foreign nations to challenge state procurement laws in domestic courts. But the terms of § 102 of the URAA and of the SAA simply does not support this argument. They refer to challenges to state law based on inconsistency with any of the “Uruguay Round Agreements.” The challenge here is based on the federal Burma law. We reject the State's argument that the National Government's decisions to bar such WTO suits and to decline to bring its own suit against the Massachusetts Burma law evince its approval. These actions simply do not speak to the preemptive effect of the federal sanctions against Burma.

25 See, e.g., Board of Trustees v.Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 317 Md. 72, 79-98, 562 A.2d 720, 744-749 (1989) (holding local divestment ordinance not preempted by Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986 (CAAA)), cert, denied sub nom. Lubman v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 493 U. S 1093 (1990); Constitutionality of South African Divestment Statutes Enacted by State and Local Goverments, 10 Op. Off. Legal Counsel 49, 64-66, 1986 WL 213238 (state and local divestment and selective purchasing laws not preempted by pre-CAAA federal law); H. R. Res. Nos. 99-548,99-549 (1986) (denying preemptive intent of CAAA); 132 Cong. Rec. 23119-23129 (1986) (House debate on resolutions); id., at 23292 (Sen. Kennedy, quoting testimony of Laurence H. Tribe). Amicus Members of Congress in support of the State also note that when Congress revoked its federal sanctions in response to the democratic transition in that country, it refused to preempt the state and local measures, merely “urg[ing]” both state and local governments and private boycott participants to rescind their sanctions. Brief for Senator Boxer et al. as Amid Curiae 9, citing South African Democratic Transition Support Act of 1993, § 4(c)(l), 107 Stat 1503.

26 The State also finds significant the fact that Congress did not preempt state and local sanctions in a recent sanctions reform bill, even though its sponsor seemed to be aware of such measures. See H. R. Rep. No. 105-2708 (1997); 143 Cong. Rec. E2080 (Oct. 23, 1997) (Rep. Hamilton).

27 See Export Administration Act of 1979, 50 U.S. C. App. § 2407(c) (1988 ed.) (Anti-Arab boycott of Israel provisions expressly “preempt any law, rule, or regulation“).

- 1

- Cited by