Article contents

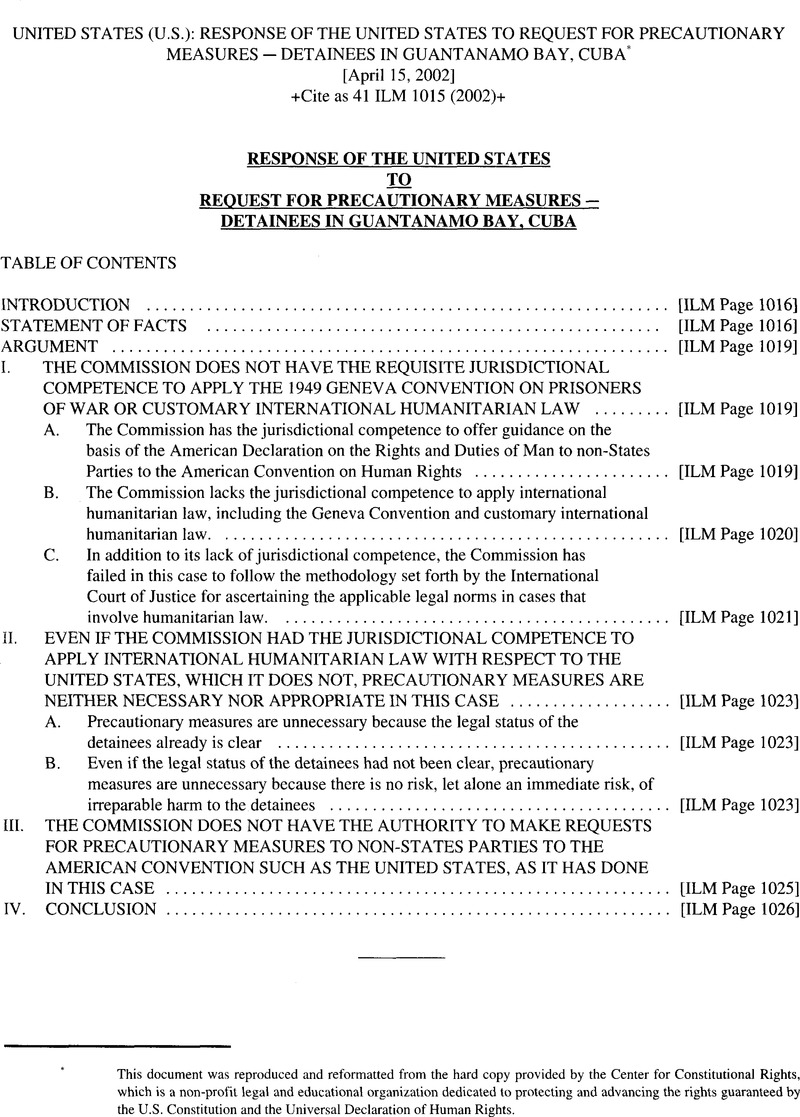

United States (U.S.): Response of the United States to Request for Precautionary Measures - Detainees in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 May 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Reports and Other Documents

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 2002

Footnotes

This document was reproduced and reformatted from the hard copy provided by the Center for Constitutional Rights, which is a non-profit legal and educational organization dedicated to protecting and advancing the rights guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

References

Endnotes

1 The term international humanitarian law, as used herein, is synonymous with the law of war or the law of armed conflict.

2 Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War of August 12, 1949, 6 U.S.T. 3316, T.I.A.S. 3364, 75U.N.T.S. 135(1949).

3 See, e.g.. Secretary Rumsfeld's statement that the detainees “are not POWs” and instead are “unlawful combatants.” Gilmore, Gerry J., Rumsfeld Visits, Thanks U.S. Troops at Camp X-Ray in Cuba, American Forces Press Service Google Scholar, Jan. 27, 2002, at <http://www.defenselink.mil/news/Jan2002/no1272002_20020127l.html> (visited April 11, 2002).

4 The U.S. Supreme Court, citing numerous authoritative international sources, has held that unlawful combatants “are subject to capture and detention, [as well as] trial and punishment by military tribunals for acts which render their belligerency unlawful.” See Exparte Quirin, 317 U.S. 1, 31 (1942) (citing Great Britain, War Office, Manual Of Military, ch. xiv, §§ 445-451; Regolmaneto Dl Servizio In Guerra, § 133, 3 Leggi E Decreti Del Regno D1 Italia (1896) 3184; 7 Moore, digest Of International Law, § 1109; 2 Hyde, International Law, §§ 654, 652; 2 Halleck, International Law (4th Ed. 1908) § 4; 2 Oppenheim, International Law, § 254; Hall, International Law, §§ 127,135; Baty & Morgan, War, Its Conduct And Legal Results (1915) 172; Bluntschi, Droit International, §§ 570 bis.).

5 Petitioners also assert that the U.S. position is that none of the detainees is “subject to the Geneva Conventions.” Petitioners’ Request at 7. This is factually inaccurate. As previously mentioned, President Bush's Press Secretary has stated publically that the Geneva Convention “applies to the Taliban detainees … .” White House Fact Sheet, Feb 7, 2002, at 1.

6 See American Convention on Human Rights, Nov. 22, 1969, 9.1.L.M. 673 (1969), arts. 34-51.

7 See American Declaration on the Rights and Duties of Man, adopted at Bogota by the Ninth International Conference of States, Mar. 30-May 2, 1946, OAS Res. XXX, reprinted in Basic Documents 15-21.

8 See Advisory Opinion of July 8, 1996, 35 I.L.M. 809, 1343 at para 25 (1996).

9 The United States takes no position with respect to countries that are States Parties to the American Convention because that issue raises separate and complex legal issues of jurisdiction and treaty interpretation not relevant to this case.

10 It has been and continues to be the United States view that Coard was decided incorrectly as a matter of fact and law, in part because the Commission applied international humanitarian law without the jurisdictional competence to do so, a view that is reinforced by the decision of the Inter-American Court in the Las Palmeras Case, as discussed previously. As stated above, the Inter-American Court held in Las Palmeras that the competence of the Court for parties to the American Convention (which the United States is not) extends only “to determin[ing] whether the acts or the norms of the states are compatible with the [American] Convention, and not with the 1949 Geneva Conventions.” Las Palemras Case, Judgment No. 67, at para. 33. Here, the Commission has violated that principle by expounding upon specific articles and provisions of the 1949 Geneva Convention on POWs.

11 75 U.N.T.S. 287-417(1950).

12 The underlying principle that a State has the authority to detain combatants for the duration of hostilities certainly is not diminished by the mere fact that a combatant is acting unlawfully, as opposed to lawfully. Geneva Convention Article 118, which sets forth release and repatriation obligations and conditions with respect to lawful combatants, i.e., POWs reflects the international humanitarian law principle that combatants may be detained for at least the duration of hostilities. The authority to detain unlawful combatants is at a minimum equal to that with respect to lawful combatants. To afford rights to unlawful combatants greater than those afforded to lawful combatants would be entirely inconsistent with the letter and sprit of the Geneva Convention, as well as customary international humanitarian law. In other words, a State engaged in armed conflict has at a minimum every right to capture and detain combatants acting unlawfully that it otherwise would have if the combatants were acting lawfully.

13 Because the Commission lacks the authority to interpret and apply the relevant humanitarian law, the United States declines to address the merits of its underlying status determinations, but reserves the right to do so at a latter time. That said, the United States notes that Article 5 tribunals are not required where, as here, there is no doubt about the status of the detainees. See Geneva Convention, Article 5 (“Should any doubt arise [regarding status] … [detainees] shall enjoy the Protection of the present Convention until such time as their status has been determined by a competent tribunal.“). Even if there were doubt, any dispute regarding their status would not be for the Commission to resolve — not only due to the Commission limited jurisdictional competence, but also as a result of the terms of the Geneva Convention, which plainly states that “alleged violation^] of the Convention” shall be dealt with “in a manner to be decided between the interested Parties.” Geneva Convention, Article 132. No party to the Convention has alleged a violation has occurred or expressed an interest in even discussing with the United States any alleged violation.

14 See, e.g.,Department of Defense, Military Commission Order No.1 (March 21, 2002), <http://www.defenselink.mil/newsfs/March2002/d20020321ord.pdf> (visited April 5, 2002).

15 See note 12, supra at 24.

- 3

- Cited by