No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 March 2017

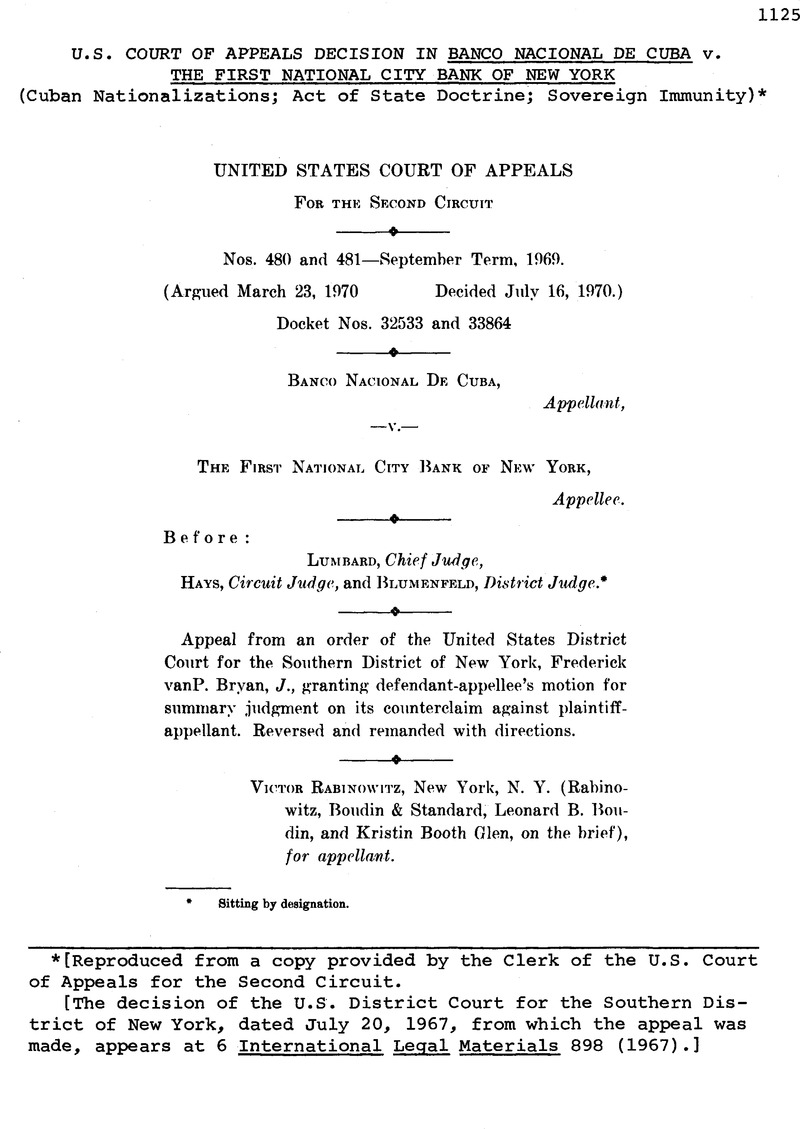

* [Reproduced from a copy provided by the Clerk of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.

[The decision of the U.S. District Court for the Southern Districtof New York, dated July 20, 1967, from which the appeal was made, appears at 6 International Legal Materials 898 (1967).]

* Sitting by designation.

1 The district court cited these laws as Cuban Law No. 730, February 16, 1960, and Cuban Law No. 847, June 30, 1960.

2 Executive Power Resolution No. 2 was issued pursuant to Cuban Law No. 851, July 6, 1960. See Banoo Nacional de Cuba v. Sabbatino, 307 F.2d 845, 849, 861-2 (2d Cir. 1962). Executive Power Eesolution No. 2 is set out in the opinion of the district court, 270 F. Supp. at 1009-1010, note 6.

3 What had happened was that a number of private Cuban banks with deposits in First National City were nationalized pursuant to Cuban Law No. 891 in October I960, and the confiscation decree declared that Banco Nacional was to have full title to the property of those banks. Thus, First National City, in notifying Banco Nacional, referred to theaccounts as Banco Nacional's.

4 We only observe that Judge Bryan's resolution of this issue was in compliance with the decision of this court in Republic of Iraq v. First National City Bank, 353 F.2d 47 (2d Cir. 1965), cert, den., 382 U.S. 1027 (1960). We also note that the holding that the Cuban expropriationdecrees are not entitled to extra territorial enforcement in United States courts as to property located within the United States is distinctfrom the question whether the act of state doctrine—absent the Hickenlooper Amendment—bars an American court from inquiry into thevalidity of expropriations of American property within the territory of the expropriated nation.

On this appeal, certain intervenors point out that they claim someof these deposits. The court below, in granting summary judgment to First National City on Banco Nacional's second cause of action, did notreach these claims, which we assume will be litigated below at some time.

5 This stipulation was entered for purposes of this litigation, to avoid the necessity of a trial on the value of First National City's expropriated assets located in Cuba. See 270 F. Supp. at 1010-11.

6 A sub-part of this argument is that, assuming the Hickenlooper Amendment applies to the facts or this case, Judge Bryan incorrectly applied international law in holding that the Cuban expropriations violated international law. However, appellant concedes that if thiscourt holds the Amendment applicable to the case at bar, Judge Bryan's decision on this issue was in accordance with the decision of this courtin Banco National v. Farr, supra, 382 F.2d at 183-185; appellant states that it raises the issue only to preserve it for further appeal.

7 Again, this issue was resolved against Banco Nacional in Banco National v. Farr, supra, 383 F.2d at 178-183.

8 Reversing Banco National de Cuba v. Sabbatino, 307 F.2d 845 (2d Cir. 1962).

9 376 U.S. at 429-430.

10 See section VI, infra.

11 See e.g., Hearings before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations on S. 2659, 8. 2660, S. 2662, and H.B. 11380, 88th Cong., 2d Sess.(1964) at 449; Hearings before the House Committee on Foreign Affairs on H.R. 7750, 89th Cong., 1st Sess. (1965).

12 “No court in the United States shall decline on the ground of the federal act of state doctrine to make a determination on the merits, or to apply principles of international law including the principles of compensation and the other standards set out in this subsection, in acase in which an act of a foreign state occurring after January 1, 1959 is alleged to be contrary to international law, and effect shall not begiven by the court in any such case to acts that are found to be in violation thereof.” (8. Rep. No. 1188, Part I, 88th Cong., 2d Sess.[1964], p. 37; emphasis added.)

13 For a discussion of these changes see Banco Nacional v. Farr, supra, 383 F.2d at 171-2, and at 171, note 5.

14 See Henkin, Act of State Today: Recollections in Tranquility, 6 Col. J. of Transnational Law, 175, 184-5 (1967); see also id. 185, n. 40.

15 The report of the Treasury Department, Office of Foreign Assets Control, on the census of blocked Cuban assets, is reprinted in Housing Hearings, supra, at 1264. The report states, as reprinted at 1264, that the Cuban assets control regulations were adopted “under section5(b) of the Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917, as amsnded, to implement the policy of an economic embargo of Cuba set forth in Proclamation No. 3447, which was issued by the President under section 620(a) of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, Public Law87-195.”

16 In 1964, when Congress enacted subchapter V of the International Claims Settlement Act of 1949, relating to claims against Cuba, it included as section 511(b) a provision vesting the blocked assets of the Cuban government in the United States government and further providing that the proceeds of such assets of the Cuban government should be used to reimburse the United States government for the expense of operating the Foreign Claims Settlement Commission and the Department of the Treasury in processing claims against Cuba. Pub.L. 88-666, section 511(b), 78 Stat. 1113 (October 16, 1964). However, that section was repealed one year later, see Pub. L. 89-262, section 5,79 Stat. 1988 (October 16, 1965). The report of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee states that “the committee was persuaded by the following argument advanced by the Department of State: it is the Department's view that vesting and sale of Cuban property could set an unfortunate example for countries less dedicated than the United States to the preservation of rights. The Governmentof the United States, as a matter of policy, encourages the investment of American capital overseas and endeavors to protect such investments against nationalizations, expropriations, intervention, and taking. To vest and sell Cuban assets would place the Government of the United States in the position of doing what Castro has done. It could cause other governments to question the sincerity of the United States Government in insisting upon respect for property rights. The result could be a reduction, in an immeasurablebut real degree, of one of the protections enjoyed by American-owned property around the world. ”Sen. R. No. 701, 89th Cong., 1st Sess., 2 U.S.C. Code Cong. & Admin. News p. 3583 (1965).It seems to us that Congress' acceptance of the State Department's argument points up to some extent the wisdom of Mr. Justice Harlan'sobservation in Sabbatino that to permit American courts to pass on the validity of expropriations would have an effect on “[relations with third countries which have engaged in similar expropriations.” 376 U.S. at 432.

17 See Report of Treasury Department, Office of Foreign Assets Control, Census of Blocked Cuban Assets, supra note 15, reprinted in HouseHearings, supra, at 1264. First National City's judgment debt to Banco Nacional for the excessamount it holds would have to be reported to the Office of Foreign Assets Control on Form TFR-607 under any one of several classificationsof “reportable property” specified on that form. The report also states that the deadline for filing reports for theOffice's census of blocked Cuban assets was March 15, 1964. However, the report notes that there are probably many people holding blockedassets who did not know of the deadline, and states “extensions of time for filing were granted when necessary.” There is little questionthat an extension would be granted in a situation such as the present case, where lengthy, litigation to settle the dispute over entitlement tothe excess funds carried the parties past the filing deadline.

18 We note from the affidavit of First National City Bank submitted below that its claims for expropriated property is relatively small,about three million dollars, as compared to some claims which must have been filed by American corporations with large industrial operationsin Cuba. ”

The windfall First National City seeks can best be understoodthrough a hypothetical example. Assume that there are twenty claimants who have filed with the Foreign Claims Settlement Commissionpursuant to 22 U.S.C. $1643 (Supp. 1970). Ten claimants, called “A” claimants, each have claims for fifteen million dollars; four claimants,called “B” claimants each claim five million dollars. The twentieth claimant is First National City Bank which, for purposes of this example,also seeks five million dollars. Further, assume that absent the sum in dispute in this case the total value of blocked Cuban assetsheld by the Office of Foreign Assets Controls is 20 million dollars. If the claims are eventually allowed to vest against the fund andsome sort of pro rata payment authorized, First National City Bank will do considerably better if it is permitted to retain the Cuban assetswhich fortuitously were in its reach, rather than if it had merely held the excess here in dispute so that in time it would have been blockedand become part of the fund.

Assume First National City has seized the collateral, sold it, andrealized three million dollars over the amount owed with interest. If, as it seeks in this suit, it keeps the three million as a set-off againstits claims against Cuba, the fund compromised of all blocked assets would still equal twenty million dollars. However, the claims againstthe fund would be reduced from 200 million to 197 million, since First National City would have to off-set the three million dollars againstthe five million dollars we have assumed it has claimed witn tne foreign Claims Settlement Commission. See 22 U.S.C. $1643 (Supp. 1970). Onthis basis, the pro rata share would be 10.9 cents on the dollar. The “A” claimants, seeking 15 million each, would each receive about 1.52million; the “B” claimants, with claims for 5 million, would each take about .57 million. and First National City, with its claim reduced to2 million, would receive about .24 million. But to this must be added the 3 million which it took directly, bringing its total recovery to 3.24million.

In the second case, First National has not (or is not allowed to)take the 3 million for its own account; rather, it stays in Banco Nacional's name and in time becomes part of the fund. Now, the fundhas 23 million, while the claims are 200 million, since First National City has nothing to off-set against its initial claim of 5 million. Here,the pro rata share would be about 11.5 cents on the dollar. The “A” claimants would receive about 1.73 million each, while the “B” claimants—including First National City—would take about .575 million each. As can be seen, by resorting to self-help and avoiding the Congressionalscheme for orderly settlement of these claims, First National City stands to profit considerably. Under our hypothetical figures, the differenceis between 3.24 million and .575 million dollars. The windfall of course is not at the expense of Cuba, but rather comes out of the sharesof all other American nationals who have lost property by the Cuban expropriation.