No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

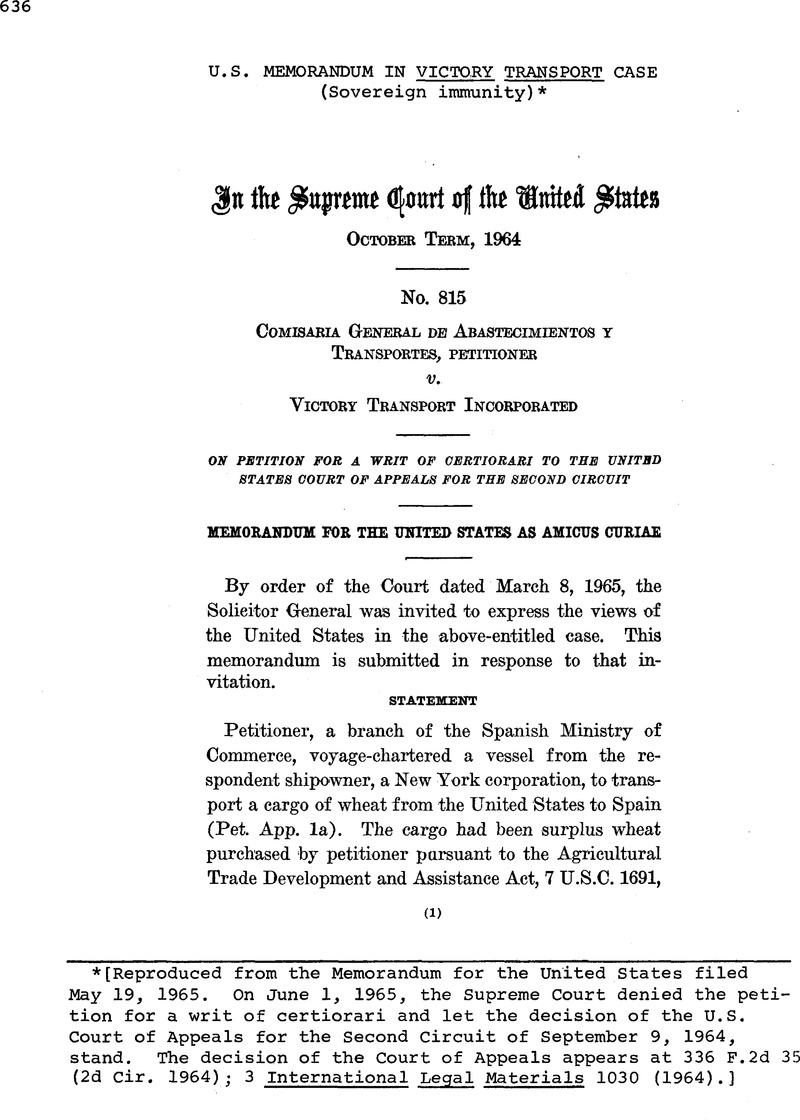

U.S. Memorandum in Victory Transport Case (Sovereign immunity)*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1965

Footnotes

[Reproduced from the Memorandum for the United States filed May 19, 1965. On June 1, 1965, the Supreme Court denied the petition for a writ of certiorari and let the decision of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit of September 9, 1964, stand. The decision of the Court of Appeals appears at 336 F.2d 35 (2d Cir. 1964); 3 International Legal Materials 1030 (1964).]

References

1 The five categories were: (1) internal administrative acts, such as expulsion of an alien; (2) legislative acts, such as nationalization; (3) acts concerning the armed forces; (4) acts concerning diplomatic activity; (5) public loans.

2 Fart v. Gia Intercontinental de Naregaekm, 243 F . 2d 342 (C.A. 2 ) ; Orion S. & T. Co. v. Eastern, States Petro. Corp. of Panama, 284 F. 2d 419 (C.A. 2).

3 The court of appeals relied upon Eule 4(d) (3), incorporated by reference into Eule 4(d)(7), which authorizes service upon a foreign corporation or unincorporated association in the manner employed in the State courts. The court also invoked Rule 4(e), which, as of the date of the service in the instant case, authorized service upon parties outside of the State whenever “a statute of the United States or an order of court provides for [such] service * * * ” The court noted that the service in this case was effected pursuant to an order of the district court(Pet. App. 18a).

4 Although we agree with the courts below that petitioner was not entitled to prevail in this action, we do not at this stage express an opinion on the Second Circuit's particular formulation of a restrictive theory of sovereign immunity or even upon the distinction between governmental acts and commercial or private acts.

5 See, e.g., The Pesaro, 255 U.S. 216; Ex parte Hussein Lutfi Bey, 256 U.S. 616; The Parlement Beige, [1879-1880] L.R., 5 P.D. 197.

6 A few years earlier, the Court of Appeal in England had also held that a vessel of a foreign sovereign used in ordinary commerce was entitled to immunity, The Porto Alexandre, [1920] P.D. 30.

7 In Mexico v. Hoffman, 324 U.S. 30, while holding that courts should normally grant or withhold immunity to foreign sovereigns “in conformity to the principles accepted by the department of the government charged with the conduct of our foreign relations” (324 U.S. at 35), the Court nevertheless specifically pointed out that “we have no occasion to consider the questions presented in the Berizzi case” (324 U.S. 35, n. 1).

8 Sovereign immunity is not an available defense with respect to prize taken in violation of our neutrality. The Santiesima Trinidad, 7 Wheat. 288, 353. Vessels owned by sovereigns but not possessed by them are not entitled to immunity. Compania Espanola v. Navemar, 803 U.S. 68; Mexico v. Hoffman, supra; Long v. The Tampieo, 16 Fed. 491 (S.D. N.Y.). Moreover, several courts in this country have held that agencies or in-strumentalities of a foreign sovereign which are separate corporate entities are not exempt from the jurisdiction of our courts. Ooale v. Société Co-op. Suisse Des Charbons, Basle, 21 F. 2d 180 (S.D. N.Y.); United States v. Deutchet Kalisyndikat Gesellschaft, 31 F. 2d 199 (S.D. N.Y.); but of.,BaccuS v. Servioio Naoional Del Trigo, [1956] 3 All E.K. 715. In addition, it is well-settled that a foreign sovereign who voluntarily appears in an action without asserting sovereign immunity, has waived the defense. The Sao Vicente, 281 Fed. I l l (C.A.2); Flota Maritima Browning de Cuba v. Motor Vessel ciudad, 335 F. 2d 619 (C.A. 4).

9 A few state court decisions have apparently indorsed the so-called “restrictive theory.” Pacific Molasses Oo. v. Comite De Ventas De Mieles, 219 N.Y.S. 2d 1018; Three Stars Trading Oo. v. Republic of Cuba, 222 N.Y.S. 2d 675; Harris and Company Advertising, Inc. v. Republic of Cuba, 127 So. 2d 687 (Fla.).

10 This Court,s decisions dealing with foreign sovereign immunity have been actions against vessels. However, the lower courts have applied the same principles of sovereign immunity in in personam actions. Oliver American Trading Go. v. Government of the United States of Mexico, 5 F. 2d 659 (C.A. 2 ) ; United States eas ret Cardashian v. Snyder, 44 F . 2d 895; (C.A.D.C.), certiorari denied, 283 U.S. 827; Puente v. Spanish Nat. State, 116 F. 2d 43 (C.A. 2), certiorari denied, 314 U.S. 627; Sullivan v. State of Sao Paulo, 122 F. 2d 355 (C.A. 2 );

Matthews v. Walton Bice Mill, 176 F . 2d 69 (C.A.D.C.); Adatto v. United States of Venezuela, 181 F; 2d 501 (C.A. 2 ) ; Loomis v. Rogers, 254 F. 2d 941 (C.A.D.C.), certiorari denied, 359 U.S. 928.

11 While the broad distinction recognized in these cases may be questionable, nevertheless it may be that in certain limited types of attempted in personam actions against foreign governments, an absolute immunity from jurisdiction over the party, should be accorded, with the court declining to inquire further to determine whether the facts of the case justify an exemption from suit. For example, where, in a claim against a foreign government, the proper party defendant is a personal sovereign, and such person is a guest in this country, a threshold absolute immunity from in personam actions should perhaps be accorded. The same may be true of ambassadors and ministers to this country. However, if such immunity is deemed appropriate, it may be more properly regarded as merely an immunity from service of process under certaincircumstances.

12 As the decisions of this Court dealing with foreign sovereign immunity have all involved actions against vessels, this Court has never directly considered the distinction which petitioner evidently urges or the nature of a sovereign's immunity in an in personam action. With regard to the nature of sovereignimmunity, this Court's opinions, all in in rem cases, have been somewhat unclear. In The Exchange, 7 Cranch 116, 137, the Chief Justice referred to the principle merely as an “exemption” from the jurisdiction of our courts. In The Pesaro, 255 U.S. 216, 218; The Carlo Poma, 255 U.S. 219; and Berizzi Bros. Co. v. S.S. Pesaro, 271 U.S. 562, 576, the Court seemed to view actions against foreign governmental property as exceptions to the district court's subject matter jurisdiction. The language of Ex parte Peru, 318 U.S. 578, 587-588, suggests that sovereign immunity is merely a legal defense, providing a ground for relinquishing jurisdiction previously acquired. See also, Ex parte Muir, 254 U.S. 522, 532; Ex parte Tramportes Maritimos, 264 U.S. 105, 108.