Article contents

World Trade Organization Appellate Body: Report of the Appellate Body in United States - Standards for Reformulated and Conventional Gasoline

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1996

References

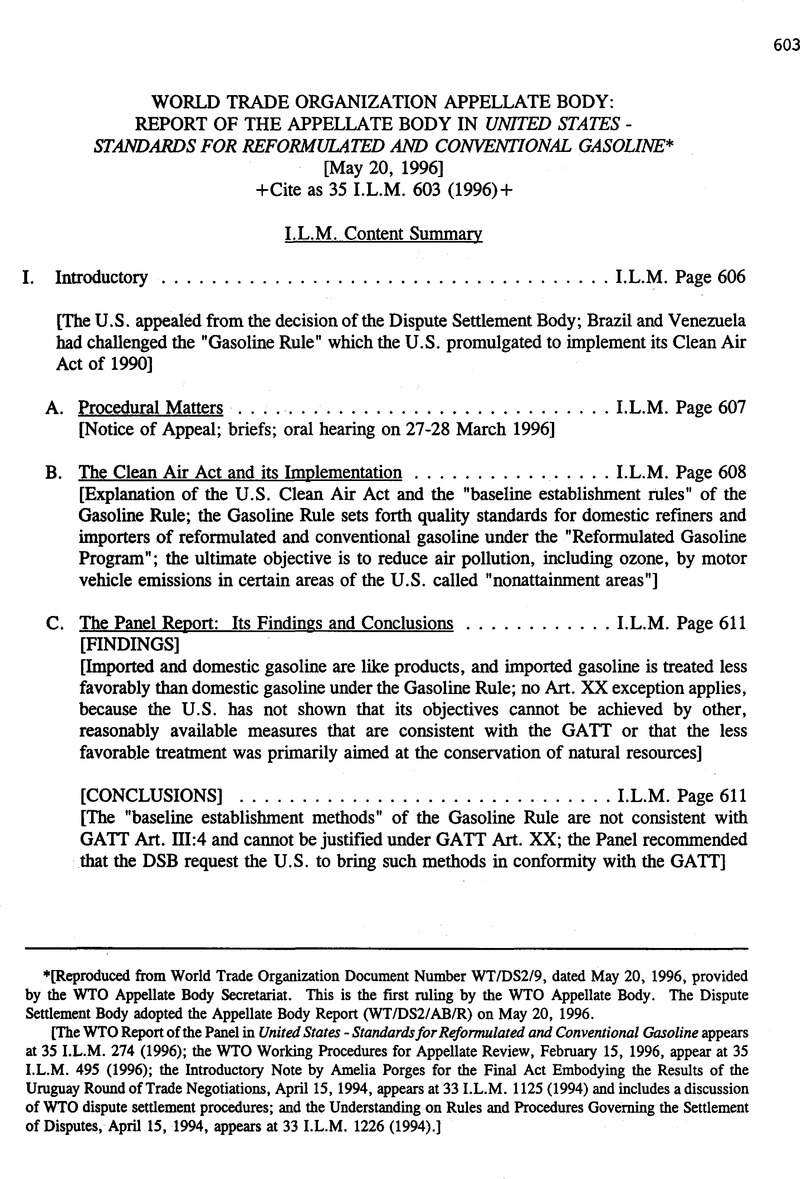

* [Reproduced from World Trade Organization Document Number WT/DS2/9, dated May 20, 1996, provided by the WTO Appellate Body Secretariat. This is the first ruling by the WTO Appellate Body. The Dispute Settlement Body adopted the Appellate Body Report (WT/DS2/AB/R) on May 20, 1996.

[The WTO Report of the Panel in United States - Standards for Reformulated and Conventional Gasoline appears at 35 I.L.M. 274 (1996); the WTO Working Procedures for Appellate Review, February 15, 1996, appear at 35 I.L.M. 495 (1996); the Introductory Note by Amelia Porges for die Final Act Embodying the Results of the Uruguay Round of Trade Negotiations, April 15, 1994, appears at 33 I.L.M. 1125 (1994) and includes a discussion of WTO dispute settlement procedures; and the Understanding on Rules and Procedures Governing the Settlement of Disputes, April 15, 1994, appears at 33 I.L.M. 1226 (1994).]

1 40 CFR 80, 59 Fed. Reg. 7716 (16 February 1994

2 WT/DS2/6.

3 WT/AB/WP/1, 15 February 1996.

4 Pursuant to Rule 21(1) of the Working Procedures.

5 Pursuant to Rule 22(1) of the Working Procedures.

6 Pursuant to Rule 24 of the Working Procedures.

7 Pursuant to Rule 25 of the Working Procedures.

8 The oral hearing was originally scheduled for 25 March 1996 but had, for exceptional and unavoidable reasons, to be deferred to 27 and 28 March 1996.

9 Rule 28 of the Working Procedures.

10 Rule 28(1) of the Working Procedures.

11 Section 21 l(k).

l2 Section211(k)(2)-(3).

13 Section 211(k)(8) of the CAA. ‘

14 Section 80.90 of the Gasoline Rule.

15 Section 80.91.

16 40 CFR 80, 59 Fed. Reg. at 22 800 (3 May 1994).

17 Panel Report at p. 47.

18 Panel Report, para. 6.19.

19 Panel Report, para. 6.16.

20 Panel Report, para. 6.17.

21 Panel Report, para. 6.29.

22 Panel Report, para. 6.33.

23 Panel Report, para. 6.37.

24 Panel Report, para. 6.40.

25 Panel Report, para. 6.41.

26 Panel Report, para. 6.42.

27 Panel Report, para. 6.43.

28 Canada - Administration of the Foreign Investment Review Act, BISD 30S/140, adopted 7 February 1984; United States -Section 337of the Tariff Act of1930, BISD36S/345, adopted 7 November 1989; United States - Taxes on Automobiles, DS31/R (1994), unadopted.

29 Although, in earlier submissions to the Appellate Body, the United States suggested that “the Gasoline Rule” should be examined in the context of Article XX(g), in its Post-Hearing Memorandum, dated 1 April 1996, the United States confirmed its understanding that the “measures” in issue are the baseline establishment rules contained in the Gasoline Rule. Brazil stated, in its final submission to the Appellate Body, dated 1 April 1996, that “the measure with which this appeal is concerned is the baseline methodology of the Gasoline Rule, not the entire rule itself.” This would suggest a position similar to that adopted by the United States. Thereafter, Brazil continued to state that “Brazil and Venezuela did not challenge all portions of the Rule; they challenged only the discriminatory methods of establishing baselines.” Venezuela stated, in its summary statement, dated 29 March 1996, that “the measure to be examined is the discriminatory measure, that is, the aspect of the Gasoline Rule that denies imported gasoline the right to use the same regulatory system of baselines applicable to U.S. gasoline, namely, the system of individual baselines.“

30 Canada - Measures Affecting Exports of Unprocessed Herring and Salmon, BISD 35S/98, para. 4.6; adopted on 22 March 1988, cited in Panel Report, para. 6.39.

31 Panel Report, para. 6.40.

32 Panel Report, paras. 6.25-6.28.

33 (1969), 8 International Legal Materials 679.

34 See, e.g., Territorial Dispute Case (Libyan Arab Jamahiriya v. Chad), (1994), I.C.J. Reports p. 6 (International Court of Justice); Golder v. United Kingdom. ECHR. Series A. (1995) no. 18 (European Court of Human Rights); Restrictions to the Death Penalty Cases, (1986) 70 International Law Reports 449 (Inter-American Court of Human Rights); Jiménez de Aréchaga, “International Law in the Past Third of a Century” (1978-1) 159 Recueil des Cours ;, p. 42; D. Carreau, Droit International (3è ed., 1991) p. 140; Oppenheim's International Law (9th ed., Jennings and Watts, eds. 1992) Vol. 1, pp. 1271- 1275.

35 Done at Marrakesh, Morocco, 15 April 1994.

36 Canada - Measures Affecting Exports of Unprocessed Herring and Salmon, BISD 35S/98, para. 4.6; adopted 22 March 1988, cited in Panel Report, para. 6.39.

37 We note that the same interpretation has been applied in two recent unadopted panel reports: United States - Restrictions on Imports of Tuna, DS29/R (1994); United States - Taxes on Automobiles, DS31/R (1994).

38 Canada-Measures Affecting Exports of Unprocessed Herring and Salmon, BISD 35S/98, paras. 4.6-4.7; adopted 22 March 1988. Also, United States - Restrictions on Imports of Tuna, DS29/R (1994), unadopted; and United States - Taxes on Automobiles, DS31/R (1994), unadopted.

39 Venezuela's Appellee's Submission, dated 18 March 1996; Venezuela's Statement at the Oral Hearing, dated 27 March 1996.

40 The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary on Historical Principles (L. Brown, ed., 1993), Vol. I, p. 786.

41 Id, p. 481.

42 Some illustration is offered in the Herring and Salmon case which involved, inter alia, a Canadian prohibition of exports of unprocessed herring and salmon. This prohibition effectively constituted a ban on purchase of certain unprocessed fish by foreign processors and consumers while imposing no corresponding ban on purchase of unprocessed fish by domestic processors and consumers. The prohibitions appeared to be designed to protect domestic processors by giving them exclusive access to fresh fish and at the same time denying such raw material to foreign processors. The Panel concluded that these export prohibitions were not justified by Article XX(g). BISD 35S/98, para. 5.1, adopted 22 March 1988. See also the Panel Report in the United States - Prohibition of Imports of Tuna and Tuna Products from Canada, BISD 29S/91, paras. 4.10-4.12; adopted on 22 February 1982.

43 This was noted in the Panel Report on United States - Imports of Certain Automotive Spring Assemblies, BISD 30S/107, para. 56; adopted on 26 May 1983.

44 EPCT/C. 11/50, p. 7; quoted in Analytical Index: Guide to GATT Law and Practice. Volume I, p. 564 (1995).

45 E.g., Corfu Channel Case (1949) I.C.J. Reports, p.24 (International Court of Justice); Territorial Dispute Case (Libyan Arab Jamahiriya v. Chad) (1994) I.C.J. Reports, p. 23 (International Court of Justice): 1966 Yearbook of the International Law Commission. Vol. JJ at 219; Oppenheim's International Law (9th ed., Jennings and Watts eds., 1992), Volume 1, 1280-1281; P. Dallier and A. Pellet, Droit International Public. 5e ed. (1994) para. 17.2); D. Carreau, Droit International. (1994) para. 369.

46 We note in this connection that two previous panels had occasion to apply the chapeau. In United States - Imports of Certain Automotive Spring Assemblies, BISD 30S/107; adopted on 26 May 1983, the panel had before it a ban on imports, and an exclusion order of the United States’ International Trade Commission, of certain automotive spring assemblies which the Commission had found, under Section 337 of the Tariff Act of 1930, to have infringed valid United States patents. The panel there held that the exclusion order had not been applied in a manner which would constitute a means of “arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination against countries where the same conditions prevail,” because that order was directed against imports of infringing assemblies “from all foreign sources, and not just from Canada.” At the same time, the same order was also examined and found not to be “a disguised restriction on international trade.” Id., paras. 54-56. See also United States - Prohibition of Imports of Tuna and Tuna Products, BISD 29S/91, para. 4.8; adopted 22 February 1982. It may be observed that the term “countries” in the chapeau is textually unqualified; it does not say “foreign countries”, as did Article 4 of the 1927 League of Nations International Convention for the Abolition of Import and Export Prohibitions and Restrictions, 97 L.N.T.S. 393. Neither does the chapeau say “third countries” as did, e.g., bilateral trade agreements negotiated by the United States under the 1934 Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act; e.g. the Trade Agreement between the United States of America and Canada, 15 November 1935,168 L.N.T.S. 356 (1936). These earlier treaties are here noted, not as pertaining to the travaux preparatoires of the General Agreement, but simply to show how in comparable treaties, a particular intent was expressed with words not found in printer's ink in the General Agreement.

47 Para. 55 of the Appellant's Submission, dated 4 March 1996. The United States was in effect making the same point when, at pages 11 and 12 of its Post-Hearing Memorandum, it argued that the conditions were not the same as between the United States, on the one hand, and Venezuela and Brazil on the other.

48 Supplementary responses by the United States to certain questions of the Appellate Body, dated 1 April 1996.

49 Panel Report, para. 6.26.

50 Panel Report, para. 6.28.

51 Supplementary responses to the United States to certain questions of the Appellate Body, dated 1 April 1996.

52 While it is not for the Appellate Body to speculate where the limits of effective international cooperation are to be found, reference may be made to a number of precedents that the United States (and other countries) have considered it prudent to use to help overcome problems confronting enforcement agencies by virtue of the fact that the relevant law and the authority of the enforcement of the agency does not hold sway beyond national borders. During the course of the oral hearing, attention was drawn to the fact that in addition to the antidumping law referred to by the Panel in the passage cited above, there were other US regulatory laws of this kind, e.g., in the field of anti-trust law, securities exchange law and tax law. There are cooperative agreements entered into by the US and other governments to help enforce regulatory laws of the kind mentioned and to obtain data from abroad. There are such agreements, inter alia, in the anti-trust and tax areas. There are also, within the framework of the WTO, the Agreement on the Implementation of Article VI of GATT1994, (the “Antidumping Agreement“), the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (the “SCM Agreement“) and the Agreement on Pre-Shipment Inspection, all of which constitute recognition of the frequency and significance of international cooperation of this sort.

53 Panel Report, para. 3.52.

54 Adopted by Ministers at the Meeting of the Trade Negotiations Committee in Marrakesh on 14 April 1994.

- 3

- Cited by