The past decade has seen a resurgence of interest in the study of leaders in International Relations (IR).Footnote 1 Who assumes the role of president, prime minister, or dictator dramatically shapes the foreign policies a state chooses, in large part because leaders systematically differ in their experiences before entering office; in their personalities, leadership styles, and operational codes; and in their traits or dispositions, like hawkishness.Footnote 2 Leader characteristics, this body of scholarship has argued, are critically important to understanding when interstate conflict is likely.

One of the critiques of the study of leaders in IR, like the study of political psychology more generally, concerns the problem of aggregation: although leaders sometimes act alone, many of the most important decisions in foreign policy are made in small groups.Footnote 3 History is replete with images of advisers at their leaders’ side at critical moments: with Otto von Bismarck during the Franco–Prussian War, Vo Nguyen Giap during Dien Bien Phu, John Foster Dulles during the Berlin Crisis, Moshe Dayan during the Six-Day War, P.N. Haksar during the Bangladesh War, and so on.

Do advisers systematically shape foreign policy behavior, and if so, how? Whether in reference to the “best and brightest” in Vietnam, or the “Vulcans” who advocated the invasion of Iraq, many popular accounts of foreign policy decision making suggest that critical foreign policy choices often hinge on whether a leader's inner circle is filled with hawks or doves. Yet much of the academic literature in IR has little to say about the role of adviser characteristics in shaping foreign policy. The new wave of “first image” IR scholarship focuses on leaders rather than those who counsel them. This is partly for substantive reasons. Foreign policy decision making is hierarchical, which might lead us to suspect that leader dispositions dominate those of advisers, that leaders tend to appoint advisers with similar worldviews, and that leaders disregard advice incongruent with their prior beliefs. The asymmetry in focus also stems from methodological considerations: thanks to large-scale data-collection efforts, we have excellent data on leader-level characteristics, but relatively little data on adviser-level ones.Footnote 4

Moreover, the scholarship that does exist tends to study advisers situationally rather than dispositionally, focusing on the quality of the group's advisory process and how leaders and advisers interact, rather than on advisers’ predispositions themselves. The bureaucratic politics literature, for example, argues that the recommendations advisers give flow from their institutional affiliation; where advisers stand depends on where they sit, rather than their own stable and enduring predispositions.Footnote 5 Similarly, a rich literature studies advisory systems from the perspective of institutional design, showing that some decision-making processes, decision-making units, and institutions yield more accurate assessments, less biased information provision, and more effective policy outcomes than others.Footnote 6 Where discussions of dispositions arise in this literature, they tend to be about how leaders’ dispositions affect the advisory structures leaders establish, rather than how advisers’ dispositions affect how advisers behave.Footnote 7 As Preston notes, we still have much to learn about whether and how adviser dispositions shape foreign policy behavior, if at all.Footnote 8

We develop a theory of foreign policy decision making that emphasizes adviser dispositions. The uncertainty, complexity, and ill-defined nature of foreign policy decision making means that leaders turn to advisers for counsel. The kind of counsel that advisers offer—the information they share, the analysis they provide, and the policies they recommend—is shaped by advisers’ core dispositions regarding the desirability and efficacy of the use of force. As a result, despite the decision-making authority that leaders retain, foreign policy choices bear the fingerprints of advisers as much as those of leaders. Against the claims of the bureaucratic politics literature, those fingerprints are not reducible to the adviser's institutional role: who occupies the most important positions of government affects where those advisers “stand” and the corresponding counsel they give. In short, our theoretical contribution is to offer a theory of foreign policy decision making that shifts the focus to advisers rather than advisory systems, to bureaucrats rather than bureaucracy.Footnote 9

To test our theory, we leverage big data and machine learning techniques to offer systematic and unusually high-resolution empirical tests of how advisers shape foreign policy. First, we located, collected, digitized, and processed the transcripts of 2,685 US foreign policy decision-making meetings from 1947 to 1988. We compiled the records through in-person collection at seven libraries and archives, as well as from online repositories. These include all available meeting records of the US National Security Council (NSC), as well as 1,894 informal meetings in which presidents discussed foreign policy issues with their advisers. We segmented each meeting transcript by speaker, meaning that our data identify not only which advisers provided counsel but also what substantive topics they emphasized. We also reviewed each transcript to manually code every decision leaders made during these meetings, which ranged from diplomatic cooperation to interstate conflict. These include some of the most consequential foreign policy choices in modern American history, such as the decision to blockade Soviet ships during the Cuban Missile Crisis and the decision to engage with Mikhail Gorbachev during the Reykjavik Summit. We believe this to be the most comprehensive resource available by which scholars can study the microfoundations of foreign policy decision making.

Second, we apply a novel machine-learning-based approach that estimates (at a distance) leader and adviser dispositions, such as hawkishness, based on an original data set of the biographical characteristics of every individual who participated in the meetings in our sample. Our biographical data describe the background and professional experience of 1,134 individuals ranging from secretaries of state to Pentagon bureaucrats—an adviser-level counterpart to the leader-level data sets that have revolutionized the study of leaders in IR. This innovation allows us to study advisers in US foreign policy on a far larger scale than has traditionally been possible, and to study quantitatively what has traditionally been the preserve of qualitative approaches. Our unique approach enables us to study not only whether dispositions shape the types of counsel that advisers provide, but also whether the aggregated dispositions of advisory groups shape the choices leaders ultimately make.

Analyzing these data yields two major findings demonstrating the central importance of advisers in foreign policy decision making. First, we find that adviser dispositions shape the counsel leaders receive when making consequential foreign policy choices. American presidents consistently solicit information from advisers during deliberations—and advisers use these opportunities to offer information, perspectives, and policy recommendations congruent with their dispositions. Second, we show that hawkish advisory groups are associated with more conflictual foreign policies, even after considering several potential pathways for selection effects. Contrary to accounts assuming that decision-making outcomes simply reflect leader dispositions, we find that adviser-level hawkishness has large and systematic effects on foreign policy decision making, and that appointment to and participation in foreign policy groups does not merely mirror the hawkishness of the leader. The theory and findings collectively illustrate the formidable influence foreign policy advisers can wield in providing the counsel leaders demand.

Leaders, Advisers, and Aggregation in Groups

The division between hawks and doves is central to our understanding of why states choose conflict over cooperation.Footnote 10 Hawks and doves differ in their beliefs about the nature of international politics, the motivations of adversaries, and the efficacy and appropriateness of using force, shaping the foreign policies these individuals support.Footnote 11 Consequently, knowing an individual's general hawkishness often predicts their propensity to endorse specific conflictual policies.

Despite the centrality of hawkishness to our understanding of policy preferences, there is debate about whether and how individual dispositions like hawkishness aggregate to shape state behavior.Footnote 12 Most foreign policy decisions occur in group settings in which leaders and advisers interact. American presidents made key decisions during episodes spanning from the Berlin Crisis to the Persian Gulf War in consultation with advisers ranging from John Foster Dulles to Colin Powell. Prior to the Soviet Union's invasion of Afghanistan, Leonid Brezhnev conferred with an advisory troika of defense minister Dmitry Ustinov, KGB director Yuri Andropov, and foreign minister Andrei Gromyko. Even Richard Nixon and Mao Zedong—known for domineering decision-making styles—routinely relied on advisers, such as Henry Kissinger and Zhou Enlai, respectively.

Like the leaders they serve, advisers presumably possess stable dispositions like hawkishness. The central question, however, is whether and how these leader- and adviser-level traits aggregate to shape foreign policy outcomes. The literature offers two points of view. The first is that the dispositions of group members (leaders or advisers) have no bearing on foreign policy decisions—an assumption shared by several disparate theoretical traditions in IR. The second is that individual traits do matter, but because foreign policy is hierarchical, decisions simply follow from leaders’ dispositions. We discuss each of these positions in turn before presenting our dispositional model of advising.

The Emergence Model

Several theoretical traditions in IR assume that the dispositions of group members should not aggregate in systematic or predictable ways. These theories offer markedly distinct justifications for this nonetheless common assumption. First, realist scholarship emphasizes that the structure of the international system creates powerful incentives for states to behave as “unitary actors.” In this view, the domestic features of the state, including the types of individuals constituting decision-making groups, have little effect on state behavior compared to structural variables, such as polarity, the balance of power, and alliances.Footnote 13 Second, some game-theoretic scholarship remains skeptical about the challenges of aggregation, suggesting that the aggregation of traits in groups is complex enough to warrant a “methodological bet” that they are not worth studying.Footnote 14 Third, a body of holist or constructivist scholarship argues that group-level outcomes cannot be reduced to attributes of the members comprising the group.Footnote 15 Just as international politics is a complex social system, so too is domestic policy making.Footnote 16 While these intellectual traditions differ dramatically, they share an assumption that when studying state behavior, the individual level of analysis is the wrong place to look: neither leader nor adviser characteristics should neatly map onto a group's foreign policy decisions, as Emergence model in Figure 1 indicates.

FIGURE 1. Three models of aggregation in groups

The Leader Model

A second view of aggregation, evident in much recent work, focuses on the traits of leaders (the Leader model in Figure 1). Simply put, some leaders are more hawkish than others, and states led by hawkish leaders are more likely to engage in conflictual behavior.Footnote 17 For example, Yarhi-Milo finds that during the Cold War some American presidents, such as Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan, tended to exhibit more hawkishness than others, such as John F. Kennedy and Jimmy Carter.Footnote 18 Studies have also noted the division between hawkish and dovish leaders in other countries, such as China and India.Footnote 19

The leader model posits that group decisions reflect leader traits for two reasons. First, foreign policy decision-making groups tend to be hierarchical: leaders enjoy more substantive and procedural authority than other group members. Leaders do not just make the final decisions in foreign policy; they also set the rules for how decisions get made. In this view, leaders might be able to impose their worldview on policy by strategically manipulating adviser appointments or participation in decision making. As Krasner argues, “The President chooses most of the important players and sets the rules … These individuals must share his values.”Footnote 20 Saunders similarly notes that leaders can shape the decision-making group by “hiring advisers or government officials who share [similar] beliefs.”Footnote 21 Byman and Pollack suggest that adviser preferences are often “determined by the leader,” rather than by the adviser's bureaucratic position or worldview.Footnote 22 Leaders might also structure the decision-making process to give privileged access to advisers with congruent dispositions. Leaders might deliberately manipulate which advisers participate in meetings, steer discussions in directions that suit their preferences, or include a “domesticated dissenter” in meetings to fabricate the appearance of debate when in fact their decision has already been made. For example, Lyndon Johnson excluded vice president Hubert Humphrey from policy deliberations on Vietnam in 1965 after Humphrey expressed opposition to escalation.Footnote 23 If leaders strictly surround themselves with like-minded advisers, or manipulate the advisory process to ensure that the information they receive predominately reflects their worldview, the real causal power comes from the traits of the leader, not those of the advisory group.

Second, the leader model argues that leader beliefs tend to supersede the input advisers provide. In this view, leaders enter office with fixed preferences and firm beliefs about the optimal strategies to achieve them.Footnote 24 When making decisions under uncertainty, leaders may privilege their own “mental Rolodex” regarding the nature of international politics, placing more emphasis on “vivid, personalized, and emotionally involving” information from first-hand experiences, rather than the abstract intelligence provided by their bureaucratic advisers.Footnote 25 Cognitive barriers, such as the desire for consistency, and motivated reasoning may also cause leaders to prioritize input from advisers with similar dispositions, such as a hawkish leader prioritizing input from hawkish advisers and a dovish leader prioritizing input from dovish advisers.Footnote 26 Thus advisers are “influential” only when the input they provide is congruent with what the leader already believes. And in that case the advisers’ dispositions are once again epiphenomenal.

Perhaps because of the presumed importance of leaders, far more of the empirical literature focuses on leaders rather than their advisers.Footnote 27 Qualitative approaches to studying elite decision making often consider advisers chiefly to illustrate the leader's importance by providing a counterfactual of what a different individual might have done in the same situation.Footnote 28 This asymmetry in focus is also likely a function of methodological considerations: in quantitative IR, we have excellent data sets of leader-level background characteristics, but as of yet, nothing comparable for adviser-level characteristics.

The Adviser Model

In contrast to the emergence and leader-centric views that much of the literature espouses, we develop a model of aggregation emphasizing advisers’ dispositions. Our adviser model is based on three simple intuitions. First, the challenges of foreign policy decision making cause leaders to turn to advisers for counsel. Second, advisers have stable predispositions about foreign policy. Third, these predispositions affect the nature of the counsel advisers provide, and thus the decisions leaders are likely to make. We discuss each of these in turn.

Our model begins with an assumption as well known to scholars of foreign policy analysis as it is to leaders themselves: foreign policy decision making is hard.Footnote 29 International politics is characterized by ill-defined problems in which the nature of the situation, the potential solutions, and even the optimal outcome are fundamentally unclear.Footnote 30 Before making foreign policy decisions, leaders must determine what type of situation they face and what information, interests, and norms are pertinent, and adjudicate between conflicting accounts, all while facing time constraints, information constraints, irreducible uncertainty, and complex value trade-offs.Footnote 31

It is here that advisers are useful. Advisers in foreign policy do many things: they offer emotional support and companionship to leaders coping with the stress of decision making, they give the leader public legitimacy and political cover, and they coerce leaders using the threat of public protest.Footnote 32 Yet advisers do not just comfort, cover, and coerce: they also counsel, which we can understand as consisting of three distinct functions.Footnote 33

First, advisers engage in information provision, giving leaders information they need about the state of the world.Footnote 34 Historically, advisers served as the king's “eyes and ears and hands and feet.”Footnote 35 Today, they monitor intelligence, diplomatic cables, and news reports. Sometimes, the answers even to questions as mundane as “What happened?” are not straightforward, even for highly experienced leaders.Footnote 36 During the Gulf of Tonkin crisis in August 1964, Lyndon Johnson and his advisers struggled for hours to determine whether North Vietnam had conducted a second attack on the USS Maddox. The sheer volume of information contemporary leaders command—by the mid-1960s, US ambassadors were sending 400,000 words a day by telegraph—means that advisers do not merely provide information to the leaders they serve but also screen it, choosing what to relay and what to hold back.Footnote 37

Second, advisers engage in problem representation, helping leaders develop a “definition of the situation” they face.Footnote 38 This function, which George called the “diagnostic” function of advising and Maoz refers to as “framing,” is less about gathering information than about interpreting it.Footnote 39 Is the conflict in Korea in 1950 a civil war or an act of communist aggression? Is Ho Chi Minh a local nationalist or a Soviet puppet? Should the uptick in violence in Iraq in 2007 be understood as terrorism or insurgency? This is why analogical reasoning is so powerful in foreign policy, since it offers decision makers schemas they can use to define what values or interests are at stake in a given crisis.Footnote 40 Much of what advisers do in foreign policy deliberations consists of offering leaders these schemas or perspectives, as reflected in documents like the memos written by McGeorge Bundy and George Ball in 1964 and 1965 with titles like “Vietnam: what is our interest there and our object?” and “How valid are the assumptions underlying our Vietnam policies?” In this sense, advisers not only provide leaders with information, but also provide them with theories.

Third, advisers provide policy recommendations, helping leaders select the optimal strategy given the situation they face.Footnote 41 Burke and Greenstein call this “reality testing,” and George calls it “option assessment,” as decision makers assess the expected consequences of different courses of action.Footnote 42 In the Cuban Missile Crisis, for example, advisers deliberated about whether the United States should respond diplomatically, with air strikes, or with a blockade. Just as strategic scripts follow from the images that precede them, advisors’ policy recommendations are intimately connected to the problem representations to which they subscribe. Jervis, for instance, noted that most of the debates during the Cold War depended on whether observers viewed US–Soviet relations through the prism of the spiral model or the deterrence model; which model you embraced determined what policies you favored.Footnote 43

Having outlined the types of counsel leaders seek from advisers, we turn to our next assumption—that advisers have stable and well-defined predispositions that shape the way they view foreign policy. Some, like Curtis LeMay and Donald Rumsfeld, are relatively hawkish, while others, like Cyrus Vance and George Ball, are relatively dovish. The notion that leaders systematically differ from one another in their predispositions—whether operationalized as ideological belief systems, personalities, worldviews, leadership styles, or operational codes—is well established in the foreign policy literature.Footnote 44 Much like the leaders they serve, advisers are forged by early experiences that continue to shape how they behave when in office decades later.Footnote 45 Experience planning Allied bombing campaigns against Japan during World War II shaped Robert McNamara's assessments of the feasibility of the bombing campaign against Hanoi during the Vietnam War. Experience touring American aircraft carriers in the early 1980s colored the views of Chinese admiral Liu Huaqing during Politburo debates in the 1990s concerning Chinese naval modernization.

Finally, we argue that advisers’ predispositions shape the counsel they provide during deliberations, and thus the decisions leaders make. Research in political psychology leads us to expect that an adviser's dispositions affect all three of the counseling functions—information provision, problem definition, and policy recommendations. Scholarship on motivated reasoning and confirmation bias argues that our predispositions affect not only the information decision makers seek out but also how persuasive they find that information to be.Footnote 46 Advisers in the George W. Bush administration, for example, were convinced that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction, so they tasked intelligence officers with looking for signs of them. Predispositions also affect how decision makers define the situation they face, responding to ill-defined problems by anchoring on their core dispositions. Hawks and doves facing the same strategic setting tend to perceive the situation in fundamentally different ways, suggesting one reason why after the Cold War hawks continued to perceive the same level of international threat even after the Berlin Wall fell.Footnote 47 Moreover, as the earlier discussion of the spiral and deterrence models showed, predispositions affect the policies we prefer. This assumption lies at the heart of hierarchical models of foreign policy preferences, which envision our more general orientations toward foreign policy (such as hawkishness) shaping our preferences regarding the use of force in particular circumstances.Footnote 48

In sum, our adviser model predicts that foreign policy decisions should reflect the dispositions of the advisers who participate in the deliberations (the Adviser model in Figure 1). The model has three sets of testable implications. First, leaders should seek advisers’ counsel. Leaders should meet with advisers, and in these meetings, leaders should ask questions, solicit advice, and request clarifications, rather than meetings merely being pro forma opportunities for leaders to keep their subordinates informed. Second, the counsel advisers offer in these meetings should depend systematically on their dispositions: hawks and doves should emphasize different pieces of information, or interpret the information in different ways, engaging in arguments and counter-arguments as they compete with one another over the direction they want leaders to take. Third, the dispositions of advisers participating in deliberations should affect actual foreign policy decisions. The more hawks dominate the discussion, the more conflictual decisions the group should make.

It is worth noting what is distinctive about our approach. First, it explicitly studies advisers dispositionally, rather than situationally. By drawing our attention to how dispositions affect the information, problem representation, and policy recommendations advisers provide, our dispositional focus not only connects the study of advisers to the study of political psychology more generally, but also leads to substantively different predictions. Unlike the bureaucratic politics literature, whose situational focus assumes that where advisers stand is based on where they sit,Footnote 49 we argue that advisers’ recommendations flow from predispositions that are not reducible to their institutional role. Second, recent scholarship has tended to focus on coercive pathways to advisory influence, showing that advisers matter because of the costs they can impose on leaders outside of meetings, such as the threat of leaks or public criticism.Footnote 50 In contrast, our model rests on a counseling pathway: advisers shape decision making because they fulfill a leader's psychological and informational needs during deliberations. Our model thus complements this recent wave of research by identifying an additional pathway though which advisers matter despite ultimately being subservient to those they are advising.

The three models of aggregation are not mutually exclusive. The leader model might explain certain decisions, while the adviser model explains others. Sometimes leaders may know both what they want to do and how they want to do it, such that no amount of information or deliberation will sway them—in which case we would expect them to manipulate the decision-making process to obtain their desired outcome. The value of theorizing an adviser model stems from the fact that there are many circumstances in which leaders are uncertain about which direction to take. Ultimately, the performance of each model is an empirical question we seek to test.

Data

To test our adviser model, we systematically collected and analyzed a large set of archival records of high-level foreign policy meetings in the United States from 1947 to 1988. We first used these records to identify the participants in foreign policy decision making. We then measured participant hawkishness (our explanatory variable) from a distance using a novel methodological approach. All data were collected specifically for this study. Figure 2 visually summarizes our main data sets and the steps taken to convert them into the measures we ultimately use to test the three models of aggregation. We describe each step here and provide details in Appendice sections 1–4.

FIGURE 2. Data set construction

Identifying Group Participants and Decisions Using Archival Records

There are a wide range of contexts we could use to study trait aggregation in foreign policy, but we focus here on the United States. As a global hegemon with the largest military budget in the world, it is a substantively important case. Crucially, the US maintains an unusually well-kept set of historical records of both formal and informal meetings from 1947 to 1988, which we assembled from two types of sources. First, a team of research assistants photographed over half a million pages of records in six presidential libraries, the US National Archives in College Park, Maryland, and several other print and digitized resources pertinent to foreign policy decision making across eight presidential administrations, from Harry Truman to Ronald Reagan.Footnote 51 Second, using an automated text-scraping protocol, we collected all records included in the Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUS) archival database. Harnessing a combination of automated filtering and manual review by research assistants, we extracted all FRUS meeting records that met two scope criteria: presidential participation and no participation by foreign leaders (that is, no diplomatic exchanges). Note that this excludes informal meetings between advisers in which the president did not participate.

The collection process yielded records for 2,685 meetings; 791 (29 percent) of these were formal meetings of the NSC, and another 1,894 (71 percent) were informal meetings (see Appendix section 1.3 for a summary). The inclusion of informal meetings is particularly important because not all presidents have used the NSC in the same way.Footnote 52 Some informal meetings featured only the president and a single adviser, while others included dozens of bureaucratic officials. We believe these data constitute the most extensive and complete collection to date of foreign policy meeting records in any country—although we do not claim that our sample encompasses all meetings the president attended.Footnote 53 The largest single set of records and decisions in our data comes from the Eisenhower administration, reflecting the extent to which Eisenhower used a highly formalistic advising system in which the NSC played an outsized role.Footnote 54

Research assistants used optical character recognition software to convert the photographs of meeting records into digital text, manually correcting text recognition errors. We then split each meeting record into what we call “speech acts”—the uninterrupted words spoken by a single individual during a meeting.Footnote 55 Our records now featured 2,685 meetings containing 104,504 speech acts by 1,134 unique participants.

Explanatory Variable: Measuring Hawkishness with Biographical Data

To test our dispositional model of advising, we need a measure of hawkishness for each of the 1,134 people identified in the meeting records. A major methodological challenge to the study of elite decision making is that researchers lack detailed information on the numerous individuals, most of them advisers, in decision-making groups. At present, there are no comprehensive data sets on adviser characteristics comparable to leader biographical data that would enable researchers to study advisers in a nomothetic way.Footnote 56 Moreover, even when researchers are able to identify which advisers participate in decision making, they lack a stable measure with which to estimate adviser traits and dispositions, such as hawkishness, at a distance. Researchers are often able to identify an individual as a hawk or dove only by observing the position they take on a particular issue.Footnote 57

A two-pronged methodological innovation addresses this challenge: we pair systematic coding of the biographic characteristics of presidents and advisers with past surveys administered to real foreign policy elites during the Cold War. This allows us to estimate the hawkishness of elite decision makers at a distance, without inferring it from the behavioral outcomes we are using it to explain.

Coding Biographical Characteristics of US Decision Makers

Ideally, we would administer surveys to all the presidents and advisers who participated in US foreign policy meetings during the Cold War. Since this is impossible, we adopt a biographical approach, building on work using policymakers background characteristics as a proxy for their unobservable traits.Footnote 58

To start, we identify all presidents and advisers who spoke at least once during the meetings in our sample. Each segmented speech act is attributed to one unique speaker. We collected information on the backgrounds and careers of these speakers, ranging from cabinet secretaries, to senior bureaucratic officials (e.g., assistant and deputy secretaries), to mid-level bureaucrats in the State Department, Pentagon, Central Intelligence Agency, and other government agencies.Footnote 59 Our coding focused on two aspects of the individual's background. We recorded their position and the dates on which the position was held; and we gathered an array of demographic variables that might affect hawkishness, including gender, birth year, education level, and political party, as well as diplomatic, intelligence, or military experience. Following Horowitz, Stam, and Ellis, we also coded combat experience by identifying deployment to a combat theater during a war involving the United States.Footnote 60 Table A5 in Appendix section 4.1 provides the coding for Henry Kissinger.

Imputing Decision-Maker Hawkishness with Elite Surveys from the Cold War

Having constructed the biographical data set of American foreign policy decision makers, our methodological innovation is to use machine learning approaches to measure adviser hawkishness at a distance. Like Carter and Smith, we incorporate machine learning methods in biographical coding.Footnote 61 Our novel contribution is to anchor our measures using information from Cold War–era surveys of American foreign policy elites administered through the Foreign Policy Leadership Project (FPLP).Footnote 62 Crucially, FPLP surveys included a battery of items measuring militant internationalism, a standard measure for hawkishness in the public opinion literature, as well as demographic questions that mirror those coded in our biographical data set.Footnote 63

We use this overlap to estimate the hawkishness of the meeting participants in our sample based on the hawkishness of survey respondents in the FPLP with similar biographical characteristics. Our measurement strategy proceeds in three steps. First, we create a measure of hawkishness averaging across a fifteen-item battery of FPLP questions that tap into respondents’ views on containing communism using force, prioritizing offensive military action over diplomacy or defensive measures, believing that the American effort in Vietnam was too limited, and so on.Footnote 64 Second, we identify the individual-level characteristics that exist in both the FPLP and our biographical data. These include gender, birth decade, level of education, military experience, combat experience, diplomatic experience, current military officer, current foreign service officer, and political party.Footnote 65 Third, we harness a series of supervised learning models to adduce the relationship between a respondent's biographical characteristics and their hawkishness in the FPLP. We adopt a boosted linear regression model—a form of ensemble learning where many simple linear models are sequentially trained and reweighted until a final model is established—as our primary method of estimating participant hawkishness. The models are fed the FPLP data, which provides explicit information the model can process to understand the relationship between biographical characteristics and individuals’ level of hawkishness according to their survey responses. To tune the hyperparameters of the boosted model, a five-fold cross-validation process is used to select the model that produces the best out-of-sample predictions. This optimal model is then used to predict hawkishness on new data, which in our case is the full set of presidents and advisers who participated in meetings in our sample. We use a bootstrapping process through which we randomly resample the FPLP survey data with replacement 1,000 times. This generates 1,000 predicted hawkishness measures for each individual, and we use the average as a measure of that actor's hawkishness.Footnote 66

In these models, one important predictor of hawkishness is party affiliation. However, we know that the Republican and Democratic parties changed their stances on foreign policy issues during the early Cold War.Footnote 67 Democrats went from being more hawkish to more dovish, while Republicans did the opposite, leading to party positions that are more broadly familiar to us today. If we ignored this shift, our measures would underestimate the hawkishness of Truman-era Democrats and overestimate the hawkishness of Eisenhower-era Republicans. To address this issue, we use longitudinal measures of partisan hawkishness assembled by Jeong to make time-conditional adjustments to the estimated coefficients for hawkishness of senior meeting participants.Footnote 68 This adjustment produces hawkishness measures that align more closely with historical assessments.

Figure 3 illustrates the predicted hawkishness measures for six senior positions in US foreign policy making—the president, secretary of state, secretary of defense, director of the Central Intelligence Agency, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (the president's senior military adviser), and national security advisor—sorted in chronological order. Chairmen of the Joint Chiefs are generally more hawkish than secretaries of state, but crucially, some secretaries of state (like Alexander Haig) are more hawkish than others (like Cyrus Vance). Figure 4 displays group hawkishness at the meeting level over time by calculating the average hawkishness of all meeting participants.

FIGURE 3. Predicted hawkishness measures for senior US decision makers

FIGURE 4. Average speaker hawkishness in US foreign policy meetings

Results I: Testing the Microfoundations of the Adviser Model

We first take advantage of our rich deliberation data to validate the adviser model's microfoundations. The analysis in this section answers two questions. First, do leaders seek counsel from advisers in foreign policy deliberations? And second, does the nature of the counsel those advisers provide depend on their foreign policy dispositions?

Leaders Seek Counsel During Deliberations

The first assumption of our adviser model is that leaders seek counsel from their advisers. The 2,685 meeting records in our data demonstrate that leaders routinely met with advisers. Our model assumes, however, that these meetings are genuinely deliberative: leaders should routinely seek counsel from their advisers, rather than merely informing them of decisions that have already been made. Deliberation also requires dissent: advisers should be willing to express opinions even when others disagree.

To check these assumptions, we examine the timing and frequency of such deliberation in meetings. Since automated methods are unlikely to capture the subtleties of deliberation we wish to identify, we generated a stratified random sample of 258 formal and informal meetings across presidential administrations (approximately 10 percent of the full sample), for which we coded our concepts of interest manually. Drawing on the study of deliberation elsewhere in political science, we developed a coding scheme (detailed in Appendix section 7.1) to identify speech acts that exhibited seeking counsel. A research assistant reviewed and coded each of the 10,682 speech acts in the random sample. Seeking counsel was defined as a speaker asking another participant to introduce new information, ideas, or recommendations into the discussion. Simply stating one's own position does not qualify as seeking counsel. Rather, speakers must have proactively asked others for their perspective. A meeting in which participants reiterated their own position over and over again in slightly different ways would be coded as having no search for counsel.

We find that US foreign policy deliberations exhibited a high level of seeking counsel, particularly by leaders. About one in three presidential speech acts—and over one in ten adviser speech acts—queried for more information from advisers. Figure 5 formalizes this intuition through a simple Cox model, in which administration is regressed on the duration of time before the leader seeks counsel. The model highlights that even the least inquisitive presidents still quickly sought counsel in their deliberations. While some of these queries might be performative, it is clear that presidents expend considerable time and effort soliciting input from advisers. This finding is difficult to reconcile with the leader model's emphasis on fixed and unchanging leader beliefs.

FIGURE 5. Leader search for counsel during meetings

One question, however, is whether these queries simply led to the identical viewpoints being expressed, ad nauseam. If leaders manipulated deliberations to ensure that only pre-approved viewpoints would be voiced, as the leader model contends, we would expect little disagreement among participants. To explore this contention, we replicated our coding process for speech acts exhibiting dissent, defined as a textual indication that the speaker disagreed with another meeting participant.Footnote 69 The data again suggest that leaders and advisers use deliberations to offer conflicting views: 15 percent of adviser speech acts and 10 percent of president speech acts in our random sample featured a dissenting opinion, and 64 percent of meetings featured some form of debate between participants. Collectively, the findings suggest that leaders seek input from advisers, and that participation allows advisers the opportunity to deliberate.

Advisers Provide Counsel Congruent with Their Dispositions

The second assumption of our adviser model is that the counsel advisers offer during deliberations depends on their predispositions. As we noted in our theory section, we can think of counsel as consisting of information provision, problem representation (or analysis), and policy recommendations. To get at information provision and analysis, we use the rich textual data in the collected records, examining the content of speech acts by hawks and doves during the meetings.Footnote 70 Drawing on existing research on hawkishness, we identified ex ante five categories of considerations that should be invoked in deliberations. First, hawks should emphasize that using violence is an effective and appropriate strategy in international politics.Footnote 71 Second, hawks should be more likely than doves to emphasize the ubiquity of threats or other “competitive elements” between states.Footnote 72 Third, both hawks and doves may be attuned to the military balance of capabilities, albeit for different reasons: hawks might emphasize the importance of primacy in material strength and power, while doves might emphasize that the balance of power limits the potential payoffs to violence.Footnote 73 Fourth, doves should tend to ascribe greater promise to diplomacy and international cooperation.Footnote 74 Finally, doves should tend to emphasize the importance of viewing international disputes from the adversary's perspective, recognizing that an adversary may face international or domestic constraints that impede a negotiated settlement.Footnote 75 The first three columns of Table 1 summarize these categories.

TABLE 1. Sample of hawkish and dovish terms

To test whether hawkish and dovish advisers exhibit different speech patterns on these topics, we employ a straightforward dictionary approach. We specify a set of nine to fourteen keywords, some of which are listed in Table 1, that capture each of our conceptual topics.Footnote 76 Using this list, we calculate the proportion of words associated with an individual adviser in a specific meeting that overlaps with these keywords (if at least fifty words in total). A total of 11,609 adviser-meeting observations, representing 100,089 speech acts (96 percent of our data), are processed in this manner.

Several examples suggest that these proportion measures effectively identify text related to our concepts of interest. For example, the text scoring highest for diplomacy comes from a meeting in June 1976, where chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers Alan Greenspan reported on a recent Puerto Rico economic summit: “It was an extraordinary meeting, especially in the context of other meetings I have attended. There was a real intellectual grappling with major philosophical issues … We may have developed a new form of international institution. We have broken down the formality and protocol of summit meetings so that true dialogue can take place.”Footnote 77 The text most indicative of military violence comes from an October 1958 meeting, in which chief of staff of the Air Force Thomas White said, “Our problem was that we must assume that the Soviets will strike first. If they do we cannot stop them by our Distant Early Warning lines. We must therefore find the number of bombers which it is logical for us to maintain in order to strike back after the initial Soviet attack.”Footnote 78

We find that hawks and doves discuss systematically different considerations, consistent with their underlying predispositions. Figure 6 plots the effect of moving from the least to the most hawkish speaker within a single administration on expected topic proportions in a speech act. The plotted effects are based on ordinary least squares (OLS) specifications that leverage the hawkishness scores described earlier, while also including administration fixed effects and controls for whether the meeting was formal and for whether the meeting record was a transcript. Consistent with theoretical expectations, hawks are more likely to address issues related to violence and threat, while doves place greater stress on diplomatic possibilities and adversary interests. Hawks’ discussions of military balance appear to overwhelm those of doves. Beyond statistical significance, these differences are substantively meaningful, despite the seemingly small magnitude of the estimated coefficients. An average adviser-meeting observation has a diplomacy proportion of 0.0045. Moving from the least to most hawkish individual reduces the expected proportion by 0.0033, or about 73 percent.Footnote 79

FIGURE 6. Effect of adviser hawkishness on topic proportions during meetings

To test whether predispositions also shape advisers’ recommendations, we drew another random sample of 425 meetings (approximately 16 percent of all meetings in our data set) and manually coded the 18,836 speech acts in them for whether each speaker was calling for a highly hawkish policy: the use of coercive force against, or conflict with, an adversary. The analysis confirms the straightforward intuition that hawks are more likely than doves to make conflictual policy recommendations. Individuals in the 80th percentile of hawkishness are 72 percent more likely than individuals in the 20th percentile of hawkishness to recommend conflictual policies. Advisers may have reasons to go “against type” to improve their persuasive power—as hawks counseling against conflict may have more appeal than doves—but on average they do not.Footnote 80

In sum, analyzing tens of thousands of speech acts in foreign policy meetings offers evidence consistent with the microfoundations of the adviser model. Deliberations give advisers the opportunity to offer counsel, and the considerations and recommendations advisers raise depend on their disposition. Hawkish advisers raise considerations emphasizing military violence, while dovish advisers make arguments emphasizing the utility of diplomacy and adversary perspectives. These dispositional differences also hold in terms of the policy recommendations they make. Next, we turn to the question of foreign policy decisions themselves.

Results II: Testing the Three Models of Aggregation

We have discussed how adviser dispositions affect the counsel they provide, but not how these dispositions aggregate to affect decision making. We now turn to our entire meeting record data to address this question. To fully test our adviser model—and compare it to the emergence and leader models—our main analysis turns to the decisions made in each of our meetings.

Outcome Variable: Conflictual Decisions

Given our interest in how hawkishness as a leader- and adviser-level disposition aggregates in foreign policy decision making, our central outcome of interest concerns policy choices aimed toward US adversaries in each meeting. To construct the outcome variable, a team of research assistants identified and classified all substantive decisions made in these meetings—thereby avoiding the truncation bias implicated by studies of decision making in IR that consider only major uses of force.Footnote 81 To qualify as substantive, a decision must have presidential approval and plausibly observable ramifications for US foreign policy. Examples include authorizing an increase in military spending, accelerating arms testing, moving military personnel or assets, altering strategic priorities, pushing for diplomatic engagement, and crafting language for public statements. Decisions that would not qualify are those that merely note the policy preferences of meeting participants, call for additional study of a topic, or establish a committee to set policy in the future.

For each substantive decision, a team of coders collected contextual background information, assigned the decision to one of several categories, and identified the target of the decision.Footnote 82 The pertinent classification categories were conflictual acts, which could be verbal or material and span from making threats to using force, and cooperative acts, which could similarly be verbal or material and span from conveying agreement to providing aid.Footnote 83 The target of each decision was the state or political organization, such as a rebel group, most directly affected by it.Footnote 84 Since the effects of hawkishness are linked to the treatment of adversaries in particular, rather than allies or neutral entities, the analysis focuses on adversary targets, with an entity's classification in this category potentially varying across time depending on the state of bilateral relations.

Our sample yielded 950 decisions toward adversaries across formal and informal meetings; 702 were conflictual, and 248 cooperative (Table 2).Footnote 85 We use these data to produce two measures. The first is a meeting's raw number of conflictual decisions toward adversaries. Because this is a count variable, the corresponding analyses use Poisson regressions.Footnote 86 The second measure accounts for both conflictual and cooperative decisions by subtracting the latter from the former. Positive values indicate a meeting that produces more conflictual decisions than cooperative ones. We use OLS regressions to analyze this variable. Distributions of these two outcomes are reported in Appendix section 3.3.

TABLE 2. Decisions regarding adversaries, by administration

Control Variables

One challenge in studying the effects of adviser hawkishness on foreign policy decision making is that adviser participation is not randomly assigned. To address these potential selection effects, we employ a two-pronged empirical strategy, beginning with a set of control variables meant to address potential confounding factors for our main analysis, and then proceeding to a more thorough set of robustness tests.

One threat to inference is that individuals appointed to the advisory team might reflect the leader's preferences regarding the use of force. To address this issue, we include administration fixed effects across several specifications to account for unobserved invariant components of each administration, particularly those that may have prompted the leader to choose a hawkish advisory team—or use advisers and advisory institutions in systematically different ways.Footnote 87 Models with fixed effects study the effect of group composition while holding the leader constant, which controls for these predilections. We further probe the question of adviser appointment later.

Another threat to inference concerns which advisers are invited to participate in which meetings. Although which advisers attend formal meetings is partly routinized, imagine a topic on which the leader is inclined to authorize conflictual decisions. Based on that inclination, the leader could skew meeting invitations toward hawkish advisers. Leader inclination would confound the relationship of interest because it is a common cause of group hawkishness (the explanatory variable for the adviser hypothesis) and policy decisions (the outcome variable). To address this selection process in our models, we manually coded the agenda topic for each of the 104,504 speech acts in our sample.Footnote 88 Using these classifications as a control variable helps minimize potential bias in the meeting's invitees.

A third concern is that advisers may be predisposed to participate when they anticipate positive reactions to their worldview. For instance, hawkish advisers may speak more when the international environment (a recent attack, for example) makes the state predisposed to pursue conflictual policies. While this concern is allayed somewhat by the dissent results presented earlier, we also include as control variables a set of system- and leader-level factors that may have motivated hawkish advisers to speak more. Following existing research, these include a variable measuring the lagged number of militarized interstate disputes challenging the US in the last five years, as well as national capabilities proxied by the US Composite Index of National Capability (CINC) score to measure military strength and economic health.Footnote 89

Additional control variables track the number of meeting participants affiliated with the Defense Department, intelligence agencies, the military, and the State Department, as bureaucratic interests may skew hawkish or dovish—as well as the (logged) total years of military, diplomatic, and intelligence experience of meeting participants.Footnote 90 Another control captures the number of attendees in each meeting, and a binary variable indicates whether a meeting was a formal meeting of the NSC, as opposed to an informal session outside it.Footnote 91

Results

The emergence model predicts that the dispositions of group members should have no systematic effect on policy decisions, whether because structural characteristics of the international system dominate or because group decisions cannot be reduced to individual-level traits. To test this model, we begin with the simplest aggregation procedure: the mean level of hawkishness of all speakers in the meeting.Footnote 92 If consequential policy choices are not reducible to the traits of individuals involved in making those choices, as the emergence model suggests, then we ought to observe no relationship between the group's average hawkishness and its policy decisions.

Inconsistent with emergence models, we find that conflictual policy choices toward adversaries rise with group hawkishness. The relationship holds across different specifications, as models 1 and 2 of Table 3 show. Regardless of outcome variable specification or the presence of control variables, the group's average hawkishness consistently has a positive effect on conflictual policy decisions.Footnote 93 The left-hand panel of Figure 7 presents the results graphically. Shifting the group's mean hawkishness from its minimum to its maximum while holding other variables constant increases the predicted number of conflictual decisions (based on model 1) by more than a factor of six.

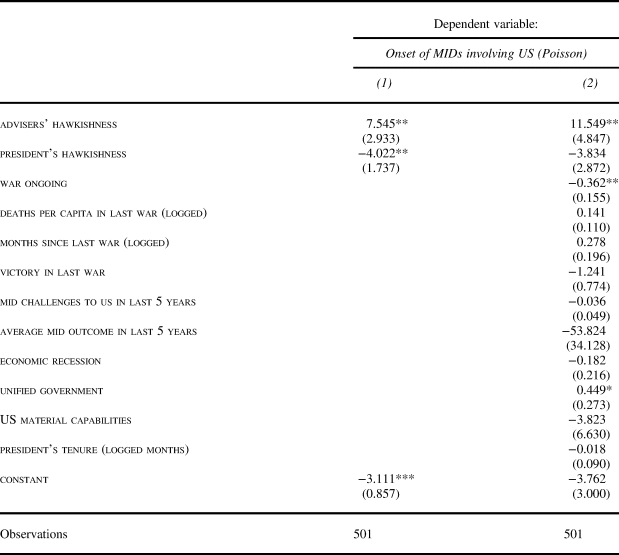

TABLE 3. Effect of participant hawkishness on foreign policy decisions

Notes: Estimates for past experience and intercept term omitted to conserve space. * p < .10; ** p < .05; *** p < .01.

Conf.: conflictual. Conf. − Coop.: conflictual minus cooperative.

MID: militarized interstate dispute. CINC: Composite Index of National Capability.

FIGURE 7. Summary of the results of three models of trait aggregation

The results demonstrate a clear, consistent, and substantively meaningful relationship between a group's composition and its decisions. Moreover, including a measure of aggregated group traits (mean hawkishness) improves the statistical model fit compared to a sparser specification without this measure. A likelihood ratio test that compares model 1 of Table 3 with a null model that omits the measure of mean group hawkishness strongly indicates that accounting for hawkishness yields a significant improvement (p = 0.0004). A similar exercise using model 2 produces an analogous result (p = 0.045). The findings thus do not support the emergence model.

The leader model predicts that leader hawkishness should systematically affect policy decisions. Whether due to group hierarchy or a leader's reluctance to hear other views, we should observe a positive relationship between leader hawkishness and conflictual policy choices.Footnote 94 Results presented for models 3 and 4 in Table 3 and the middle panel of Figure 7 suggest that presidential hawkishness does not have a systematic relationship with conflictual decisions toward adversaries.Footnote 95 Appendix section 6 details a range of potential explanations for why leader-level hawkishness may not be positively associated with conflictual decisions, ranging from strategic interaction to the uniquely institutionalized context of the United States. Similarly, replications and extensions of Horowitz, Stam, and Ellis as well as Carter and Smith in Appendix section 6.2 find little evidence that presidential hawkishness predicts American conflict behavior, consistent with Yarhi-Milo's recent work.Footnote 96 We also obtain similar results when measuring presidents’ hawkishness using measures derived from codings provided by experts of American foreign policy (Appendix section 6.1), as well as using a different operationalization of the dependent variable (Table 5). As with most studies of presidential decision making, a sample of eight leaders limits the conclusiveness of these results because the idiosyncratic nature of a single president could be exerting an outsized effect on the results. Within these confines, however, our analysis offers little support for the leader model.

The adviser model predicts that the hawkishness of advisers affects decision outcomes in deliberations. If advisers exert influence through the counsel they provide, then meetings in which hawkish advisers speak frequently ought to produce more conflictual decisions. For these models, we calculate a weighted average of adviser hawkishness, where each adviser's weight is a function of the proportion of speech acts they contributed to the discussion, reflecting our emphasis on communication as a vehicle for influence.Footnote 97

As models 5 and 6 show in Table 3 and the right-hand panel of Figure 7, we find strong evidence that adviser hawkishness affects decision outcomes. Meetings in which more hawkish advisers speak more tend to adopt more conflictual policies toward an adversary. This pattern appears across specifications. Holding other variables fixed, shifting the group's weighted hawkishness from the minimum to the maximum more than triples the expected number of conflictual decisions (based on model 5's specification). Models 7 and 8 drop the leader measure so that we can include fixed effects to guard against the possibility that results reflect differences between different presidents’ management style or preference for formal (NSC) versus informal meetings.

To further contextualize the substantive effects, Table 4 presents the predicted number of conflictual decisions toward an adversary for all fully specified models. These calculations shift each relevant measure of hawkishness from its minimum to its maximum value while holding other variables fixed at their means, and while presenting the substantive effects of other contextual variables to provide a benchmark. The table shows the dramatic effect of both the mean and weighted-mean measures of group hawkishness, which cast doubt on the emergence model and provide evidence consistent with the adviser model, respectively. In the leader versus adviser models, it is worth noting that even though the president and advisers have cross-cutting effects on decision making, the more conflictual nature of hawkish advisers appears to outweigh the effects of the president, lending further support to the importance of advisers. Collectively, the results suggest that the leader model is incomplete, and that we must consider the dispositions of advisers in the room.

TABLE 4. Predicted number of conflictual decisions toward adversaries

Selection and Robustness

Three additional questions regarding selection effects merit consideration. First, we noted earlier that administration fixed effects help identify the effect of adviser dispositions within each administration by holding constant unobserved variables, such as leader-level differences in advisory arrangements. Yet one potential question is whether this methodological choice masks influence that leaders exert through the appointment process. Leaders make appointments for a variety of reasons, including appointee qualifications, personal connections, and public approval. If leaders appointed only those advisers who shared their foreign policy worldview (for example, hawkish presidents appointed only hawks), then the advisory environment—and our results—would simply represent an extension of the leader's disposition. But we see no evidence for this. Mixed-effect models that include administration random effects find that the intraclass correlation ranges between 0.037 and 0.179: there is approximately 5.6 to 27 times as much variation in hawkishness within individual administrations as there is between them. We would expect a far smaller figure if hawkish leaders simply hired hawkish advisers or invited them to meetings.

One reason advisers are not simply dispositional mimeographs of the leaders they serve is that adviser appointment can be affected by multiple considerations, such as a candidate's education, experience, qualifications, personal connections, and fit for the position—not just their hawkishness.Footnote 98 Moreover, many leaders prefer viewpoint diversity in their advisory group, either to improve the quality of foreign policy debates by considering multiple perspectives, or to bolster their domestic credibility.Footnote 99 For every example of hawkish leaders like Ronald Reagan selecting dispositionally similar advisers, like Caspar Weinberger, there are also examples of leaders like Barack Obama selecting dissimilar advisers, like Hillary Clinton.

Second, even if leaders do not merely select mimeographs as their advisers, they may still have the ability to decide when these meetings take place and which advisers are invited, in ways that controlling for meeting agendas might fail to capture.Footnote 100 To address this concern, we replicate our results using an alternative model specification that ignores our meeting data altogether and instead examines the effect of adviser-level hawkishness (limited to NSC principals) on the United States’ propensity for being involved in militarized interstate disputes in a given month. Our findings remain the same (Table 5), despite a different unit of analysis (the time unit rather than the meeting level) and a more restrictive dependent variable (militarized interstate disputes, rather than all foreign policy decisions). This strongly suggests that, even if leaders attempt to manipulate the advisory group or fabricate deliberation in ways that accord with their own worldview, advisers are still able to sway foreign policy decisions in aggregate. Appendix section 5.9 replicates our meeting-level analysis for formal gatherings using the characteristics of only NSC principals, who are obligated to have a presence at every meeting. The results remain consistent. Adviser predispositions appear to be significantly associated with interstate conflict, even controlling for a host of international, domestic, and leader-level variables.

TABLE 5. Effect of National Security Council principals’ hawkishness on militarized interstate disputes (MIDs), using monthly data

Notes: Advisers’ hawkishness reflects average hawkishness score of senior advisers in a given month. See Appendix section 5.8 for details. * p < .10; ** p < .05; *** p < .01.

One might also ask whether our conceptualization of adviser hawkishness is specific to the Cold War—perhaps making our findings an artifact of the highly competitive US–Soviet relationship. Two factors discredit such an interpretation. First, the militant internationalism measure we use to impute decision-maker hawkishness has been widely used since 1991.Footnote 101 In fact, Murray shows that hawkish beliefs among American decision makers were surprisingly consistent before and after the Cold War.Footnote 102 Second, we run a robustness check where we drop decisions involving the Soviet Union from our analysis and find that results remain generally consistent (Appendix section 5.6).

Finally, given space constraints, our analysis here focuses on establishing that adviser dispositions affect the counsel they provide leaders in deliberations, and the decision the leader makes—rather than the follow-up question of when leaders are more likely to heed advisers’ counsel, which we explore in other research. Nonetheless, important recent work by Saunders suggests some possible scope conditions to our findings, such that leaders may be less likely to be swayed by their advisers when leaders are more experienced and when dovish leaders are paired with dovish advisers.Footnote 103 In Appendix section 5.11, we use our decision-making data set to test both propositions. We find that, at least when it comes to adviser hawkishness, neither leader–adviser gaps in experience nor leader–adviser gaps in predisposition significantly moderate the effects of adviser traits. Across the Cold War, hawkish advisers in the United States were able to push decision making in a hawkish direction no less under experienced leaders than under inexperienced ones; similarly, hawkish and dovish advisers appear to influence hawkish and dovish leaders alike. Second, one of the virtues of our main analysis is that it avoids aggregation bias by considering the universe of substantive decisions being made at the meetings, but this raises questions about whether our results are the artifact of lower-stakes decisions rather than the high-stakes decisions made in crises. To ensure this is not the case, we check that the effects of adviser dispositions remain significant both in and out of international crises featuring decision making on high-stakes issues (Appendix section 5.10).

Conclusion

Foreign policy decisions are made in groups, but whether for theoretical or methodological reasons, we know much more about the role of leader-level dispositions in shaping foreign policy outcomes than adviser-level ones. In this article, we develop an argument linking adviser dispositions to consequential foreign policy choices about peace and conflict. We test our proposition by introducing a new methodological approach that estimates, at a distance, the hawkishness of over 1,100 American advisers and presidents who participated in over 2,600 of the most important foreign policy meetings from 1947 to 1988 for which archival records exist. Our theoretical and empirical innovations allow us to move beyond conceptualizing advisers as fungible extensions of leaders and systematically study the ways they matter, particularly for questions of interstate conflict.

The theory and findings suggest that leaders’ characteristics by themselves are insufficient to explain many foreign policy decisions. While we emphasize that the leader and adviser models are complementary, we show that leaders consistently turn to advisers for counsel during consequential foreign policy meetings, that adviser dispositions shape the type of counsel leaders receive, and that shifting from a maximally dovish to a maximally hawkish advisory group triples the expected number of conflictual decisions coming out of a meeting. These dynamics illuminate an intuitive and compelling reason that advisers wield such influence: even experienced leaders confront numerous policy challenges on which they are relatively uninformed and hold few preconceived notions. And even when a leader knows what they want, they are often open to disparate perspectives concerning the numerous possible strategies for how to get it. Advisers provide the information, analysis, and recommendations leaders demand.

More broadly, our findings cast doubt on a long-standing tradition in IR arguing that the “aggregation problem” renders the study of group-member attributes an unfruitful path of inquiry. Our argument instead emphasizes that deliberation is a crucial and under-explored conduit through which individual-level dispositions, such as hawkishness, affect foreign policy outcomes. Aggregation does not forge, ex machina, a tabula rasa within the group. Knowing the dispositions of the advisers who dominate policy debates has substantial explanatory power for state behavior.

The basic logic of our adviser model suggests that leaders depend on advisers for psychological and informational reasons, which suggests broad applicability across countries beyond the United States. Yet three core elements of the model also imply corresponding scope conditions. First, because advisers must be able to provide counsel congruent with their disposition without fear of leader retribution, our model may be less applicable in authoritarian regimes, particularly personalist ones, in which leaders can severely and arbitrarily punish advisers who disagree.Footnote 104 Second, because advisers must have access to the leader, the adviser model may offer limited insight into countries with bureaucratic institutions designed to exclude advisers from decision making, such as China during Deng Xiaoping's early years.Footnote 105 Third, since leaders must be at least somewhat receptive to the counsel that advisers provide, the adviser model may not apply under leaders who are extremely closed-minded for either situational or dispositional reasons.Footnote 106

Our adviser model suggests a wide-ranging agenda for future research. Most broadly, it calls for more scholarly attention to leaders, advisers, and the institutions that connect them. Yet this study intentionally sets aside several questions that subsequent scholarship could explore. First, it does not differentiate between cases where advisers are successful in shaping decision making because leaders rely on their counsel to form beliefs on issues they have not fully considered, versus cases where advisers successfully persuade leaders to change their views. Future scholarship could leverage the data we introduce to tease apart these two mechanisms.

Second, while we provide evidence suggesting that what happens during deliberations matters to a leader's decision, it is also possible that advisers’ influence depends on efforts they made to set the agenda and build bureaucratic coalitions prior to deliberations. It is also possible that some advisers are more influential than others, and that past deliberations shape future ones in intriguing, path-dependent ways.

Third, while our primary aim in this manuscript is to show how advisers matter systematically for outcomes of broad concern to the field of IR, these dynamics are clearly the final set of steps in a long causal chain. A more comprehensive approach would systematically study the stages antecedent to entering “the room where it happens”—from institutional design, to adviser appointment, to adviser attendance, to adviser behavior, to the decision.

Finally, scholars might apply our approach to other international behaviors. Traditionally, the field of IR has studied foreign policy either through rich qualitative examination of archival documents or through quantitative methods that focus on state behavior rather than decision making. The method developed here offers a middle path: to study state behavior by quantitatively analyzing archival documents that span an extended period, but in a way that still directly observes the decision-making process.Footnote 107

Data Availability Statement

Replication files for this article may be found at <https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/GZW94R>.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this article is available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818323000280.>

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Institute of Quantitative Social Science and the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs at Harvard University for their logistical support, and to Diana Agdashian, Saadi Ali, Perry Arrasmith, Christine Bienes, Florian Bochert, Lexa Brenner, Alexis Carraway, Youmna Chamieh, Erica Colston, Joshua Conde, Vanessa Cordova, Jacinta Crestanello, Caroline Curran, George Dalianis, Charlie Davis, Darius Diamond, Iain De Boer, A.J. Dilts, Jelena Dragicevic, Corbin Duncan, Will Engelmayer, Karla Flores, Kendrick Foster, Angela Fu, John Gehman, John Gleb, Hope Ha, Joolean Hall, Joseph Hasbrouck, Sarah Jacob, Joshua Kelley, Joel Kesselbrenner, Samantha Ku, Jacob Kuckelman, Max Kuhelj Bugaric, Zaki Lakhani, Johannes Lang, Steven LeGere, Isabel Levin, Rachel Levine, Daiana Lilo, Angel Lira, Clare Lonergan, Parker Mas, Holly McCarthy, Alexandra McClintock, Sean McGuire, Deja McKnight, Scarlett Neely, Yihao Niu, Denise Nzeyimana, Christine Ow, Clay Oxford, Nic Pantelick, June Park, Marc Prophet, Kasey Quicksill, Janna Ramadan, Bianca Rodriguez, Kay Rollins, Noah Schimenti, Isabel Slavinsky, Bruno Snow, Matthew Stafford, Randle Steinbeck, Ollie Sughrue, Hannah Suh, Claire Sukumar, Maya Taha, Sal Vidal, Matthew Von, Eileen Walsh, and Taylor Whitsell for research assistance, as well as to Bear Braumoeller, Brandis Canes-Wrone, Austin Carson, Jeff Carter, Jeff Colgan, Sarah Croco, Lindsey Dolan, Peter Feaver, Ben Fordham, Matt Fuhrmann, Joe Grieco, Rick Herrmann, Katherine Irajpanah, Marika Landau-Wells, Jeffrey Lantis, Erik Lin-Greenberg, David Lindsay, Matt Malis, Rose McDermott, Jim Morrow, Phil Potter, Brian Rathbun, Elizabeth Saunders, Ken Schultz, Todd Sechser, Al Stam, Jessica Weeks, Rachel Whitlark, and audiences at APSA, ISA, Brown, Duke, Michigan, NYU Abu Dhabi, UConn, UVA, Vanderbilt, and WSU for helpful feedback. Thanks also to Keri Lemasters, Brooke Moore, Amy Desiderio, Cory Gillis, and Sarah Pollack for making the study possible. Authors listed in alphabetical order.

Funding

This research was funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (grant no. W911NF1920162).