On 23 May 2021, the Belarusian government forcibly diverted a Ryanair passenger plane to land in Minsk. After the plane landed, Belarussian police removed and arrested a prominent Belarussian dissident, Roman Protasevich. The United States and the European Union “strongly condemn[ed] … this shocking act,”Footnote 1 declared it a “brazen affront to international peace,”Footnote 2 and threatened sanctions against Belarus. But the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs sprang up in defense of Belarus, claiming that the US and the EU had “responded very differently to similar events … in the past” and demanding that they “refrain from double standards.” The ministry noted that in 2013, following (inaccurate) intelligence reports, the US government had forced the plane of Bolivia's then-president Evo Morales to land in Vienna so it could arrest intelligence leaker Edward Snowden.Footnote 3

Russia's reaction to the diversion of Ryanair flight 4978 exemplifies a frequently used rhetorical tool in the international arena: whataboutism.Footnote 4 States use this kind of rhetoric in strategic narratives or value-laden accounts of an international event with the aim of persuading domestic and foreign elites and publics. By contesting and shaping the norms of the international system, such narratives seek to constrain the freedom of action of other state actors.Footnote 5 The international relations literature does not explain why states use whataboutism. While whataboutism may appear similar in style to the “naming and shaming” strategy in international relations, it differs in important ways. Unlike shaming, whataboutism is used to undermine norms and is employed in a reactive manner. Whereas shaming involves a first-mover action, usually by nonstate actors, seeking to shame others, whataboutism is a tool used by states targeted by accusations (such as shaming). These two rhetorical approaches are supported by different underlying mechanisms and motivations.

Second, the literature on public diplomacy has not addressed whataboutist rhetoric, focusing usually on positive (rather than negative) public diplomacy, such as states’ efforts to improve their image among foreign publics.Footnote 6 Third, the burgeoning strategic narratives literature treats whataboutism as ineffective propaganda.Footnote 7 However, some studies find that audience identity and nationalist predispositions influence receptiveness to propaganda narratives even if recipients are skeptical of both the message and the messenger.Footnote 8 More generally, most of the literature assumes that narrative reception among elites and broader publics operates in a simple and direct manner: more exposure to narrative leads to more influence. This assumption fails to account for how the various aspects of rhetorical communication (such as its content and the identity of the messenger) might affect the receptiveness of foreign publics to a particular narrative.

While the theoretical literature in international relations ignores or dismisses the possible impact of whataboutism, policymakers have long acknowledged its effectiveness. Jake Sullivan, US national security advisor in the Biden administration, described it as a “dangerous” strategy that could potentially “stunt America's global leadership.”Footnote 9 And after Russia's armed takeover of Crimea in 2014, President Obama dedicated an entire speech in Brussels to countering the Russian government's whataboutist claims that its actions there were comparable to US actions in Kosovo in 1999 and in Iraq in 2003.Footnote 10 Earlier generations of American decision makers shared similar beliefs and fears about whataboutism. In 1985, the Reagan administration organized and funded a special conference in Washington, DC, dedicated to refuting Soviet whataboutist comparisons of the 1983 US invasion of Grenada to the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.Footnote 11 Many commentators and journalists also believe in the narrative-shaping power of whataboutism. A 2021 editorial in the New York Times strongly supported the Biden administration's view of the diversion of Ryanair flight 4978 by extensively countering Russia's whataboutist claims.Footnote 12

Given its extensive use, how might whataboutism influence foreign domestic audiences? From an international legal standpoint, there is scattered evidence that it sometimes works. For example, during the Nuremberg trials, admiral Karl Donitz escaped punishment by the tribunal for Germany's unrestricted submarine warfare during World War II after his defense attorney presented strong evidence that the US Navy had used its submarines in a similar manner in the Pacific Theater, illustrating how whataboutism may alter understandings of international law.Footnote 13 Nevertheless, there is little systematic research on the broader effect of whataboutism on foreign elites and publics. In this paper, we examine a key audience to see how and when whataboutism works to influence foreign policy views of its targeted public.

Based on two survey experiments, we find that whataboutism significantly reduces US public support for criticizing and penalizing other countries’ behavior. It does so in several ways. First, whataboutism uses rhetorical coercion to persuade foreign publics that certain misdeeds are more acceptable to bolster the perception of the target country's virtue. Second, it sows mistrust of the moral legitimacy of the government as the proper agent to criticize or act against the state employing whataboutism. However, to our surprise, the efficacy of whataboutism is unaffected by the identity of its purveyor or its favorability in the eyes of the target public. We also find that efficacy is reduced when the alleged misdeeds of the target government are less relevant due to the comparisons being either too far apart in time or too dissimilar in content. On the other hand, the effects are robust to a variety of plausible counter-messages by US government officials.

These results illuminate the reasons for the use of whataboutism and indirectly shed light on key limits of related “name and shame” tactics, which seek to mobilize public opinion against targets by highlighting moral transgressions. When clear grounds exist to accuse the shaming actor of double standards due to its own misbehavior (or the misbehavior of the countries of its main funders or membership), name-and-shame campaigns become vulnerable.

We organize the paper as follows. First, we review the literature on whataboutism and distinguish it from related international rhetorical strategies that employ allegations of hypocrisy, like name and shame. Second, we present our arguments on whataboutism and the accompanying hypotheses. Third, we describe the research design for our two survey experiments, followed by the results and findings. We conclude by considering the implications of this study.

The Logic of Whataboutism

While frequently described as a Cold War rhetorical tactic of the Soviet Union, whataboutism has much older origins. In a famous New Testament story, Jesus tries to save an adulterous woman from the legally prescribed punishment, death by stoning, with the suggestion, “He that is without sin among you, let him cast a stone at her first.”Footnote 14 Its traditional Latin name, tu quoque, dates to at least as far back as the seventeenth century. More recent uses of whataboutism in official government statements and propaganda date back to the nineteenth century and include many state actors, including Russia.Footnote 15

Despite its long-standing use by governments and private actors, we know little about whether and when whataboutism effectively persuades audiences in the international arena. A small body of research in philosophy, logic, and argumentation, as part of a wider philosophical research effort on logical fallacies, also considered whataboutism (or in its technical Latin term, tu quoque) as one member of the ad hominem family of logical fallacies, and studied whether and when it is actually a logical fallacy.Footnote 16 However, most of this research did not empirically investigate its effect among the general population.

Two exceptions—the studies of Bhatai and Oaksford and Van Eemeren, Garssen, and Meuffels—provide initial evidence that whataboutist arguments might persuade audiences in some circumstances.Footnote 17 They were designed to empirically analyze the persuasiveness of whataboutism (and other ad hominem counters) as well as a logical argument. In these experiments, Speaker A made an initial one-sentence argument. Speaker B responded with (1) a whataboutist argument (tu quoque); (2) other ad hominem attacks, like calling the speaker stupid or dishonest; or (3) a logical counterargument with no ad hominem content. Participants were then asked to evaluate the reasonability of Speaker B's response. Whataboutist arguments were usually seen as more reasonable than the other ad hominem attacks but less reasonable than supposedly more logical arguments. This relative reasonability depended on the topic, with significant differences for political and personal topics but not scientific topics.

These pathbreaking studies have several limitations. First, due to their theoretical focus, neither study compared whataboutism to a null response, so the effects could be driven by the mere occurrence of a response. Second, they did not examine international contexts, which may differ. Third, they focused on the relative persuasiveness of ad hominem arguments and, as they themselves noted, did not consider many potentially relevant contextual factors, such as speaker identity, that could influence responses.Footnote 18 Fourth, the samples were restricted and small—either small groups of high school students (Van Eemeren, Garssen, and Meuffels) or a small (n = 140) convenience sample (Bhatai and Oaksford), which limits generalizability.

Another body of research discusses a different foreign policy tool that uses accusations of hypocrisy, “naming and shaming”: when foreign actors, such as international governmental or nongovernmental organizations, publicly denounce states for violating international norms or obligations they claim to uphold. Naming and shaming is often effective in swaying public opinion within the shamed country.Footnote 19 On the other hand, there is growing evidence that shaming by foreign actors can lead, in many cases, to a backlash in the shamed country, preventing or reducing compliance.Footnote 20 However, the possible scope conditions for success and the potential limits to naming and shaming posited by some scholars remain underexplored.Footnote 21

First, naming and shaming in the international arena is typically limited to human rights and environmental issues. Effects of charges of hypocrisy may differ on national security issues, as is commonly the case when it comes to whataboutism, where public attitudes differ.Footnote 22 Second, naming and shaming occurs under conditions more favorable to its users. Accusers usually have a more positive image (e.g., the UN or Amnesty International) and no recent “baggage” of “bad” acts. Third, shamers act first, in a “prosecutorial” manner, against the targeted state.

In contrast, whataboutism is a defensive, second-mover strategy used by actors facing credible allegations of misdeeds. Its very nature potentially casts doubt on the whataboutist actor's motives and the credibility of their charges. Accordingly, the whataboutist actor faces higher hurdles in “moving the needle” in the target public compared to the shaming actor. While both rhetorical tactics use accusations of hypocrisy, these differences suggest analyzing whataboutism separately.

We build on naming-and-shaming research but note whataboutism's defensive use, broader issue focus, and the damaged public image of the whataboutist actor—all of which raise the bar for persuading the target public. Whataboutism, by cultivating a discourse in which all actors are equally blameworthy, tries to fully undermine the credibility of criticism and thus discourages meaningful change. This is in contrast to naming and shaming, which distinguishes between blameworthy actors and other, better-behaving actors on the issue of concern, and thus may create an opening for effective criticism and behavioral modification. Thus, whataboutism differs from naming and shaming both conceptually and in practice. Still, analysis of whataboutism may yield insights for the naming-and-shaming literature.

A third relevant and growing body of research by scholars in international relations, US foreign policy, and public diplomacy has investigated whether non-costly messages from various foreign actors influence domestic publics in general (and Americans in particular)Footnote 23 and foreign nonstate actors such as the United Nations.Footnote 24 This research finds that domestic audiences are indeed attentive and responsive to such foreign messages. In fact, foreign actors can sometimes shape the views of the targeted public on certain international issues. This has been seen even in situations where the domestic government invested significant resources in mobilizing public support for a contrary viewpoint, such as in the run-up in the US to the 2003 Iraq War.Footnote 25

This research also finds that even domestic populations historically insulated from such messages, such as the US public, are in practice increasingly exposed to foreign voices during US foreign policy debates. This makes foreign messaging an increasingly common part of such debates.Footnote 26 However, the literature has thus far not investigated the effects of whataboutism employed by foreign state actors.

How Whataboutism Affects Foreign Public Opinion

We argue that whataboutist rhetoric employed internationally undermines public support at home for a government's criticism of other countries’ bad behavior and for demands for punishment of said bad behavior. We defend this argument with three central claims.

First, in the context of the US government's projected international image,Footnote 27 whataboutism discursively traps Americans who value US exceptionalism into normatively accepting misdeeds, undermining support for punishment.Footnote 28 Whataboutism is used as a tool of rhetorical coercionFootnote 29 against the US government's complaints about a foreign country's misdeeds; it works by recounting comparable or identical activities by the US. This potentially undermines the frequent claims by US governments that the US is a uniquely upright and exceptional country, forcing a choice between cognitive dissonance or the concession of moral equivalence. To avoid the latter, Americans touting exceptionalism may end up concluding that these particular deeds are not “that bad,” or even normatively acceptable. Thus, whataboutism coerces acceptance of the foreign misdeed to avoid a costly rhetorical concession.Footnote 30

Second, whataboutism can reshape Americans’ views on whether other countries’ actions were norm violating. Many Americans are ignorant of world affairs,Footnote 31 but even those who are more informed frequently lack knowledge of common international practices, laws, or norms regarding other countries’ activities. And due to time and space constraints, the media rarely provide this context when covering global events. For example, most media reporting on the diversion of Ryanair flight 4978 did not discuss whether Belarus's actions were legal under the relevant international law.Footnote 32 Coverage focused on the incident and its consequences rather than the deeper context. The general reader could not properly judge the legal and normative merits. Their views were open to persuasion by the most compelling account—potentially a whataboutist one alleging comparable US actions. Views on domestic policies frequently reflect ideological identities (for example, on abortion) or other attachments, but foreign policy attitudes on events like this lack that grounding.

In this situation, public opinion can be more readily swayed by whataboutist narratives providing new information about problematic behavior by the accusing country.Footnote 33 Recent survey experiments show that providing accurate information to Americans about the US government's foreign policy (such as the true size of its foreign aid budget) or of common international norms and practices (such as the international laws relevant to certain US foreign activities) significantly impacts public attitudes.Footnote 34 Whataboutist rhetoric may similarly persuade by revealing unflattering US practices.

Third, governments need domestic legitimacy for their foreign policy actions—the legitimacy of certain actions abroad requires providing persuasive explanation to the public that these actions are consistent with existing domestic norms and social values.Footnote 35 Foreign policy actions that lack socially acceptable reasons can lead to quiet disobedience or outright opposition to these actions in general, and to their issuer in general. Thus the need by policymakers to justify and legitimize their key foreign policies to domestic (and sometimes foreign) audiences is an overlooked yet important aspect of the policymaking process that determines the successful execution of foreign policies in most democracies and authoritarian regimes.Footnote 36

Whataboutism rhetorically exposes the US government's own moral flaws, either in general or in regard to a type of activity, which may reduce US citizens’ trust in their government's ability to appropriately administer any punishments.Footnote 37 If it adopts a “who are we to judge” attitude, the public may end up opposing concrete actions by its own government, even if no underlying shift occurs in public views on the appropriateness of the action by the foreign government.Footnote 38

Finally, by casting doubt on the accuracy of the government's official explanation, whataboutism can raise citizens’ suspicion that their own government has ulterior, less legitimate motives for its policy. That in turn can reduce its credibility on this topic.Footnote 39

H1 Whataboutist rhetoric reduces overall public support for US critiques of the foreign actor's actions and related punishment imposed on the foreign actor.

We also expect that the effectiveness of whataboutist arguments will vary based on the argument itself and contextual factors relating to the identity of the maker of the argument. The first characteristic relates to the relevance of the US government misdeed pointed out by the whataboutist actor to the misdeed first criticized by the US government. Two factors can affect this relevance: its empirical similarity to the latter misdeed, and its overall timing. The similarity varies greatly. In the case of the diversion of Ryanair flight 4978, the two misdeeds were very similar. In other cases, the whataboutist actor cannot find, or is unwilling to use, such a good match. For example, during the Cold War, the Soviet Union, regardless of the specific US government charges, consistently pointed to the severe mistreatment of African Americans in the US.

It is plausible that less empirical commonality between the original charge and the whataboutist counter weakens the impact of the whataboutist argument. The more dissimilar the case, the less exculpatory or relevant the new information will seem. Greater empirical differences will make it easier for the American public to believe that the US is the appropriate actor, to dismiss the alleged American misdeed as irrelevant or unrelated in moral terms to the US's own perceived moral standing, and to believe that the US government's motives in this case are aboveboard. The fact that someone was once, say, caught stealing merchandise from a store may not be seen as greatly reducing their standing to criticize others or their perceived honesty in making an accusation, if the accusation is, say, about someone cheating on their spouse with another person.Footnote 40

The second key characteristic that affects the perceived relevance of a whataboutist claim is the proximity in timing. An entrenched belief in modern Western thought reduces the moral culpability for one's misdeeds as they recede into the past—in fact, responsibility may be completely absolved if enough time has passed. This widespread belief is now codified into law, with many Western countries exempting people from prosecution and punishment for crimes, even very serious ones, after some period.Footnote 41 The longer the time between the misdeeds that are being compared, the more logically plausible prima facie it is that the culprit's world views or values have “evolved” since the misdeed, such that it no longer reflects their current self.Footnote 42

By extension, the more time has passed since the US misdeed in question, the greater the likelihood that the American public will consider it irrelevant to current “proper” conduct by other countries, and see the US government once again as the appropriate commentator on this topic. Specifically, greater temporal distance between the misdeeds will lead the American public to accept the motives of the US government as honest and treat its long-ago misdeeds as part of a gradual “moral evolution,” blunting the efficacy of the whataboutist charges.

H2 Whataboutist critiques pointing to more similar misdeeds by the US will be more effective than those pointing to dissimilar ones.

H3 Whataboutist critiques pointing to more recent misdeeds by the US will be more effective than those pointing to past misdeeds.

The identity of the whataboutist actor also affects public support. This is seen sometimes in the research noted earlier on the effects of costless foreign messages. Messages from foreign actors perceived as friendly by the target public are sometimes seen as credible, and vice versa. For example, research on the 2003 Iraq War has found that messages from foreign states seen by the US as relatively friendly, such as key Western European allies, were taken quite seriously by significant parts of the American public in the run-up to the Iraq warFootnote 43 and even affected US media framing of the debate over the war.Footnote 44 Similar results about the effectiveness of messaging on various policy issues from friendly states were found in experimental studies as well.Footnote 45 In particular, one study hypothesized that the success of US government's framing of its military interventions in the 1980s (such as Grenada), which led the American public to largely ignore the handful of critiques by foreign countries of these interventions, was in part due to the identities of those countries.Footnote 46 In other words, most of the reported foreign critiques of American intervention were from countries already seen as hostile by Americans, such as the Soviet Union. One of the few analyses of current Russian whataboutism to date, a qualitative analysis of the effects of Russian whataboutism and other tactics on the EU, argued that such tactics were not likely to be effective given that the EU sees Russia as an “other” morally unequal to itself.Footnote 47 Based on this research, we would expect whataboutism strategies to be more effective with the US public when the whataboutist actor is perceived as a relatively friendly state.

H4 Whataboutist critiques by foreign actors perceived as friendly to Americans will be more effective than ones by foreign actors seen as hostile.

Research Design

We conducted two survey experiments to test our hypotheses. The first, in August to September of 2021, surveyed 2,452 US adult citizens and tested our main hypotheses. A follow-up in January 2022 with 3,200 US adults checked the robustness of our results to US rejoinders to whataboutism. Both experiments used the online survey firm Lucid. We recruited online samples that stratified survey participants by age, gender, geography, and racial/ethnic composition to broadly represent US national population samples.

Studies have found that Lucid's samples more closely resemble the demographic composition of national populations than samples from Amazon's Mechanical Turk.Footnote 48 More generally, polling from internet samples that condition on sample selection and post-stratification weighting has been found to perform just as well as probability sampling from random digit dialing,Footnote 49 or slightly worse if no effort is made in sample selection.Footnote 50 However, internet samples can have attentiveness issues.Footnote 51 We address these problems with manipulation questions to evaluate respondent attentiveness and find that our results are unaffected (see Figures A11 and A12 in Appendix A4 for details). While both experiments were fielded during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, replications of pre-pandemic online survey designs during the pandemic suggest that these conditions would not qualitatively change the results.Footnote 52

Before describing the details of the first survey, we explain the logic behind the issue-area selection (refugees and election interference) used to construct the scenarios for testing our hypotheses. We argue that these scenarios should satisfy three conditions. First, the selected issue area should have ample evidence of similar past and present American transgressions, making them ideal targets for whataboutist rhetoric. Second, the target country of US criticism must also realistically be willing and able to commit a similar act in the selected issue area. Third, the issues we test should reflect as much as possible the multiple concerns American respondents have in regard to foreign affairs, to capture any possible variation in reaction to our whataboutist treatments when different concerns are foremost on their mind.

To address these conditions, we constructed whataboutist scenarios that capture the two key concerns many Americans have in regard to US foreign policy: national security and international norms.Footnote 53 The first scenario describes a refugee crisis involving abuses of the human rights of refugees in the receiving country; and the second, a case of interference (partisan electoral intervention) by a foreign power in the elections of a democratic American ally.Footnote 54 We selected both topics to satisfy experimental realism, which will ensure that respondents give real answers rather than hypothetical ones.Footnote 55 To this end, Druckman and Kam recommended selecting issues salient to the respondents.Footnote 56 This will help them respond in a manner consistent with how they would have behaved in a similar real-world setting. Both topics are chosen to satisfy this realism condition.

Regarding the human rights vignette, the severe mistreatment of refugees is unfortunately common in many countries around the world, both democratic and authoritarian. Accordingly, an experimental scenario in which we describe a wide range of countries being criticized by the US government for such violations, from its Western European allies to staunch adversaries such as Russia, would be quite realistic. The plausibility and salience of this scenario to respondents are expected to be particularly high due to the extensive media attention to the (mis)treatment of refugees by various countries over the past decade (such as the crises over Syrian, Libyan, and Burmese/Rohingya refugees). At the same time, past and recent US treatment of refugees has also had problems, from some of the ways the US government has treated Central American asylum seekers, such as its child separation policy at the US–Mexican border,Footnote 57 to the turning away of Jewish refugees fleeing from Nazi Germany prior to World War II.Footnote 58 These cases make refugee abuse cases ideal for whataboutist rhetoric scenarios, since the targets of US government criticism for failing to uphold human rights obligations regarding refugees could subject the US to similar criticisms.

Regarding the election-interference vignette, a wide range of countries have recently intervened in foreign elections. Russia famously intervened in the 2016 and 2020 elections in the US and is accused of covertly meddling in many others, such as the 2017 French elections. And Russia is no exception in this regard. For example, Turkey under Erdogan intervened in the 2017 German elections, which led to widespread concerns of possible Turkish intervention in France's 2022 elections as well.Footnote 59 And for its part, Germany has intervened in other European elections, such as the 2012 French and Greek elections.Footnote 60 Accordingly, a scenario describing electoral intervention by any of these three countries in a future foreign election (or specifically a French one) would be quite plausible.

As a result of Russia's interference in the 2016 US election, such foreign meddling has become a greater part of media reporting. At the same time, stopping and preventing such meddling against itself and its allies has become a significant and salient national security concern for the US government and the American public. One increasingly common method used by the US government in dealing with foreign election interference since 2016 involves the exposure or denouncement of such foreign interveners, followed at times by economic sanctions of various kinds.Footnote 61

However, the US government itself also has an extensive record of intervening in foreign elections. According to the available information on this topic, since 1946 the US has been the most frequent intervener in foreign elections.Footnote 62 This situation makes electoral interventions highly useful for testing whataboutist arguments, given that US government criticisms of other countries’ electoral interventions can be countered by pointing to the US record in such activities. Indeed, some countries have done just that.Footnote 63

The experimental design is shown in Figure 1. Participants were randomly assigned to the human rights or election-interference vignette, then read background context. Following this introduction, respondents were randomly assigned to one of three countries that had committed a refugee or election interference transgression and were subsequently criticized and threatened with sanctions by the US.Footnote 64 The election interference vignette began:

In 2027, US intelligence discovered that [country] intervened in France's presidential election against the incumbent president. The [country] government secretly gave the pro-[country] opposition candidate 60 million dollars for use in their election campaign. The funding was provided in a mixture of cash and encrypted USB-drives with cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin. A US government spokesperson publicly exposed the intervention and denounced [country]'s intervention in France's election, calling it “unacceptable behavior.” The US promised future actions to punish [country] for its interference in France's presidential election.

Figure 1. Main experimental design

For the human rights vignette:

In 2027, a major humanitarian crisis in the Middle East has led to a large influx of refugees to [country]. The [country] government placed refugees in temporary detention centers, which human rights groups have criticized for its substandard food and medical treatment and overcrowded facilities. There are scattered reports of widespread violence by guards towards the refugees and sexual assault of female refugees throughout the detention centers. [Country] further plans to deport all refugees, including unaccompanied children, back to their home countries. There are widespread reports that some of those already sent back have died of non-natural causes. A US government spokesperson criticized [country]'s response to the refugee crisis, saying: “We are deeply troubled by the conditions in the detention centers and the threat of deporting refugees back to conditions that would physically endanger them.” The US warned [country] of future actions to punish [country] for the way it is mistreating the refugees.

[Country] was randomly drawn from Russia, Turkey, or Germany. After reading about the US's criticism, participants were randomly assigned to read one of five responses:

• No comment: The [country] government spokesperson did not give a public response to the US statement. Instead, all media inquiries to [country] were addressed as “no comment.”

• Denial: A [country] government spokesperson denied any involvement in France's election. The spokesperson stated, “The accusation of [country] meddling in elections of other countries is absurd / [country] complies with all international laws on the treatment of refugees.”

• Three whataboutist responses: A [country] government spokesperson accused the US government of using double standards in its criticism of others, claiming that the US [unrelated / past / relevant]. Experienced independent factcheckers have confirmed the accuracy of [country]'s claim about [unrelated / past / recent].

◦ Unrelated (same for both vignettes): … that the US has tortured hundreds of suspected terrorists in the Guantanamo military base and other locations around the world … the use of torture by the US government.

◦ Past and relevant (election vignette): … in the past has intervened in a similar manner in at least twenty-three elections around the world between 1946 and 1959. Like [country], the US has frequently intervened by funding its preferred candidates’ election campaign with millions of dollars … past US electoral interference in other countries.

◦ Past and relevant (refugee vignette): … in the past illegally jailed and placed over 127,000 Japanese Americans in concentration camps during World War II and sent back thousands of Jewish refugees back to Nazi Germany where many of them subsequently died in the 1930s … past US migration and detention policy during the 1930s and World War II.

◦ Recent and relevant (election vignette): … that the US continues to intervene in a similar manner and has done so in at least twenty-three elections since 2000. Like [country], the US frequently intervenes by funding its preferred candidates’ election campaign with millions of dollars … recent US electoral interference in other countries.

◦ Recent and relevant (refugee vignette): … continues to detain refugees by the US-Mexican border in inhumane living conditions and frequently deports these migrants, including unaccompanied children, back to their home countries despite well-documented cases of migrants dying of unnatural causes upon their return … recent US migration and detention policy.

This resulted in 3 × 5 = 15 variations. See Appendix A2 for a more detailed description of the human rights and election-interference vignettes. Participants saw both vignettes; the order was randomized, with no qualitative effect on the results (see Appendix A4 for details). After viewing each vignette, participants reported their approval of US behaviour, on a scale from 1 (strongly disapprove) to 5 (strongly approve),Footnote 65 and their support for punishing the targeted country, also on a five-point scale.Footnote 66 We preregistered our main hypotheses with the Open Science Framework, and both experiments received research ethics approval from our academic institution.

We ran a follow-up survey experiment to replicate our main finding and check whether US government rejoinders to whataboutism reduce its effect. We fielded a slimmed-down version of the main experiment comparing recent/similar whataboutist rhetoric against the US to our original null conditions, with the addition of treatments where the US government responds to the rhetoric (Figure 2). As in our main experiment, respondents saw both issues (in random order) and were randomly assigned a whataboutist country. However, here we added three US rejoinders: dismissal, admission of guilt, or justification (wider context or democracy promotion).

Figure 2. Follow-up experimental design

We based these rejoinders on typical US reactions to foreign policy criticism: dismissing the charges, admitting fault but noting reforms, or justifying the actions. Given issue-area differences in justification feasibility, the justification was democracy promotion in the election vignette or wider context in the refugee vignette. In the elections vignette, the US claimed “better” motives (democracy promotion) to weaken similarities. In the refugee vignette, the US claimed superior treatment of refugees to contextualize its actions. A detailed explanation of our choice of responses can be seen in the section on rejoinders, later in this paper.

Specifically, respondents read: “When asked about [country]'s comments the following day, a US Department of State spokesperson responded, [dismissal / democratic motivation (context) / admission of guilt].” Details for the related US response:

• Dismissal (both issues): “We must not let [country] distract us from its own unacceptable behavior by raising irrelevant issues.”

• Democratic motivation (elections): “Unlike [country]'s recent intervention in France, the US government's interventions in foreign elections were done to promote and protect democracy around the world.”

• Context (refugees): “The US provides more humanitarian assistance than any other single country worldwide. Since 1975, the United States has accepted more than 3.3 million refugees for permanent resettlement—more than any other country in the world.”

• Admission of guilt (elections): “Unlike [country], the US government has carefully reviewed its policies on election interference and is now strongly committed to ensuring that its actions are consistent with America's democratic values.”

• Admission of guilt (refugees): “Unlike [country], the US has investigated the complaints regarding its treatment of refugees at the border with Mexico and has taken measures to improve the refugee's situation.”

We analyzed our data using a linear probability model, binarizing the dependent variables,Footnote 67 with only treatment variables as independent variables. We also recorded participant political attitudes, along with demographics such as self-identified racial/ethnic background, age, gender, political party affiliation, income, foreign policy views, and attitudes toward the specific country under US criticism. We asked about these aspects because Democrats, younger individuals, and women are more supportive of certain US foreign policy actions with regard to human rights and national security. Finally, given the coronavirus pandemic in progress at that time, we asked about its health and economic impacts. For detailed robustness checks, including description of these measures, analyses with the inclusion of these controls, and discussion, see Appendix A4.

Results

We begin by investigating whether whataboutism affects overall support for US foreign policy. Figure 3 displays the effect of whataboutism on (a) approval of US behavior and (b) support for punishing the target with economic sanctions. The horizontal axis displays the mean percentage of respondents who approved or supported. Whataboutist arguments significantly reduced both values—in the first case by eighteen points,Footnote 68 and in the second by ten points—compared to the no-comment situation. These effects remain qualitatively the same when we use the denial of wrongdoing, rather than no comment, as the baseline.

Figure 3. Impact of whataboutist arguments on US policy approval and sanctions support

These results strongly support H1: whataboutist rhetoric reduces public support for the US government's criticism and punishment of foreign countries’ actions. We also find the expected variation between the different types of whataboutist charges. Comparisons to similar and more recent US misdeeds generate the strongest disapproval of US criticism and punishment of foreign governments, while mention of similar but past acts by the US has a smaller effect. Here, compared to the baseline of no comment, past and similar whataboutist charges reduce public approval of US policy by thirteen points and public support for sanctions by nine points (H3). For the unrelated whataboutist claim, the effect is more muted: there is a significant reduction of seven points in support for US behavior but no significant difference from the no-comment control for sanctions (H2). In the appendix we examine possible differences between sociodemographic groups but see little variation aside from age, with younger respondents being slightly less affected than older ones.Footnote 69 Together, these findings illustrate that the effect of whataboutism is quite strong, though it varies with the exact content.

Surprisingly, the effect does not depend on the identity of the country in question (Figure 4). We find nearly identical drops in approval and support whether the criticized country is an ally or adversary of the US: for Russia, US approval and sanction support dropped by twenty-one and twelve points, respectively; for Germany, by twenty-two and eight points, respectively.

Figure 4. Impact of whataboutist arguments on approval and sanctions, by country

The results for Turkey, the most neutrally viewed country, are less consistent. While we still observe declines in approval and support for the US, the magnitude appears smaller than for Russia and Germany. This unexpected finding may partly stem from pre-existing views of Turkey evoked by the refugee vignette. In the appendix (A4), we split the analysis by issue area and observe that respondents who read the refugee crisis vignette with Turkey as the whataboutist messenger behaved differently from those who saw Germany or Russia. These attenuation effects may be attributed to participants already knowing about Turkey's role in the recent real-world Syrian refugee crisis, thus “infecting” their responses. This effect does not occur for the election-interference vignette. Thus we observe no systematic evidence for differences between Turkey and other countries.

That the identity of the messenger does not matter may also be due to differences between whataboutism and other public diplomacy strategies.Footnote 70 Whataboutist narratives remind or inform the target audience of facts about their own country's actions. As a result, whataboutism does not seem to depend on their view of the messenger. This contrasts with influence strategies designed, for example, to change the audience's attitude toward the messenger or its actions by imparting knowledge of the country or positive speech acts and “good deeds” toward the audience.Footnote 71 Indeed, some evidence suggests that messages from low-credibility messengers can still persuade if they are verifiable through independent sources or align with what the audience already knowsFootnote 72—which may reflect the dynamic at work in whataboutism's insensitivity to messenger identity.

Why Does Whataboutism Constrain Foreign Policy?

Here, we investigate three of the mechanisms, alluded to earlier, through which whataboutism could affect public support for specific foreign policy objectives: rhetorical coercion through conveying moral equivalence between the criticizing and the targeted country, decreasing the legitimacy of the criticizing country to act in this situation, and reducing the credibility of the criticizing country. These mechanisms were measured by asking respondents whether they agreed with the following statements: (1) [Country] is morally equivalent to the US in [respecting the sovereignty and domestic autonomy of other countries / its commitment to human rights]; (2) The US is the best country to assume the responsibility of policing other countries that undermine [democracy / human rights]; and (3) US criticism of [country] reflects a genuine US government commitment to [protecting democracy / supporting human rights].Footnote 73 We use respondents’ answers to these questions as mediators.

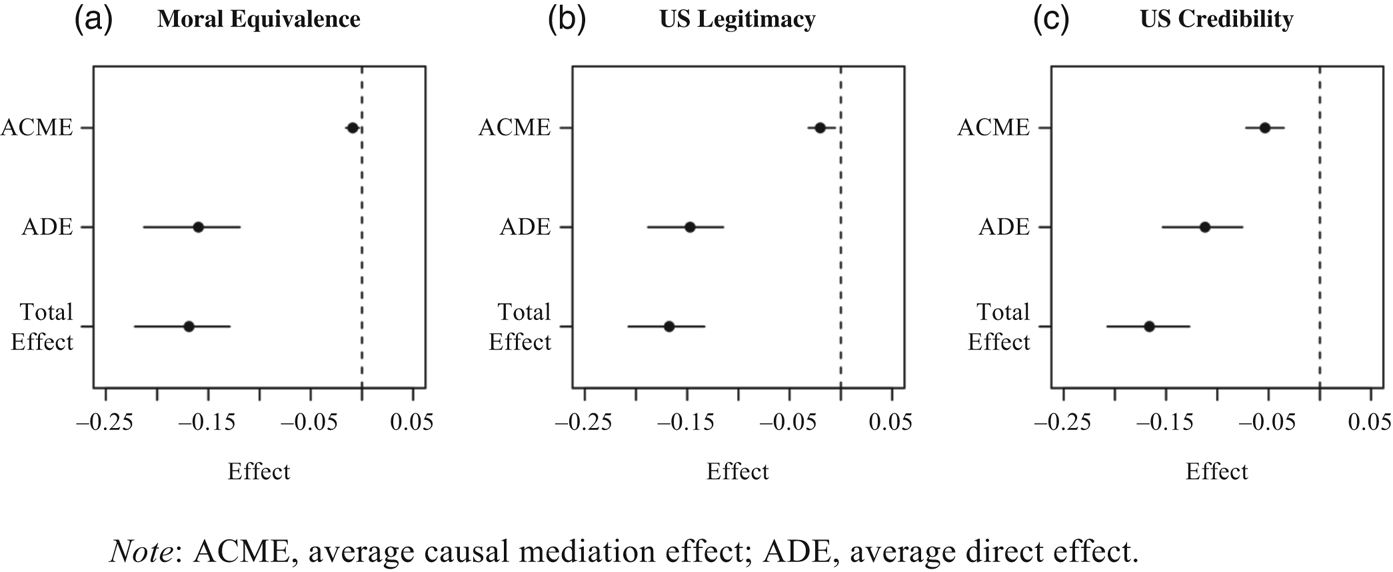

Figure 5 displays how each of these mediators influenced whataboutism's impact on public approval of US behavior. For this analysis, we compared only the recent-and-similar whataboutist treatment and “no comment.” Whataboutism reduces public support for US foreign policy in all three ways, but mostly through undermining US credibility. The average causal mediation effect (ACME) through US credibility is negative for public approval of US behavior (Figure 5c; ACME −0.053; p < 0.001): that is, whataboutism reduces the credibility of US criticism on a particular issue area, which reduces public support for the criticism in question. Similar but weaker effects are also found for the other two mechanisms of rhetorical coercion, labeled “Moral Equivalence” and “US Legitimacy” (ACME −0.01, p < 0.001, and ACME −0.02, p < 0.001, respectively).Footnote 74

Figure 5. Mediation analysis of approval of US behavior

These results provide strong evidence that whataboutism severely reduces public support for US policy by undermining the moral credibility of American global activism. The reduction of US moral superiority and the legitimacy of American activism account, respectively, for 5.1 percent (Figure 5a) and 12.1 percent (5b) of the loss of public support for US behavior. However, nearly 32 percent is driven by the loss of US credibility on the issue area in question. Together, the mediation results provide a starting point for understanding how whataboutism affects public support for US foreign policy.

Causal mediation analysis requires a properly identified model, which imposes a theoretic structure on what the responses should be. To obtain a less structured, micro-mechanism test of our argument, we also asked respondents an open-ended question about why they did or did not approve of the US government's behavior. We used structural topic modeling (STM) on the responses to generate topics or identify words used in the selected topic to study how whataboutism affects respondents’ explanations for their approval of the US government. Using STM for survey experiments works better than simply generating topics from structured machine learning, because researchers can integrate treatment covariates as a natural contributor to topic variance.Footnote 75

Using STM on responses by issue area (election interference and refugee crisis), we leverage the model by identifying which topics appear more frequently for respondents exposed to unrelated, past, and recent whataboutist rhetoric compared to no comment and denial.Footnote 76 We present the results by first comparing the point estimates of topical prevalence. Then we discuss a set of representative comments from respondents, which we used to derive the substantive labels.

Figure 6 shows the four topics most frequently mentioned in respondents’ rationales regarding the issues of election interference (6a and 6b) and refugee crisis (6c and 6d), showing frequency of mention (vertical axis) versus exposure to the various whataboutist treatments (horizontal axis). Figure 6 is paired with Table 1, which displays some representative responses.Footnote 77 We used these comments to identify the topics shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Topic prevalence of open-ended responses about the US government's behavior

Table 1. Representative responses for related topics

Respondents who read the “no comment” and “denial” null scenarios were 50 percent more likely (compared to those who read the “relevant and recent” scenario) to view American criticism as justified because it protects democracy (Figure 6a). One respondent wrote, “We should denounce any meddling in free and fair elections”; and another, “We must make sure that all elections are fair across the globe.” These comments reflect support for US criticism based on protecting fundamental values of democracy.

In contrast, respondents who read the “relevant and recent” scenario were 50 percent more likely to perceive American actions as hypocritical compared to the group that read “no comment” (Figure 6b). One respondent wrote, “It's hypocritical. They signal virtue while committing the same sort of act. Hypocritical, but sadly expected”; and another, “Pot calling the kettle black. Do as I say not as I do.” Together, these comments match our earlier causal mediation analysis (see Figure 5b) on how whataboutism undermines public credibility of US intervention abroad.

Similar to the pattern observed for democracy protection, respondents who read the “no comment,” “denial,” or “unrelated” scenario were 37 percent more likely to express approval of American human rights defense efforts, compared to those who read the past or recent scenarios (Figure 6c). One wrote, “We should always speak out when human rights are violated”; and another, “Because when there is a bully you gotta call them out and confront them. The one thing bullies hate? Being called out for what they truly are.” Together, these comments reveal a basic preference for action by the US government when human rights abuses occur in refugee centers.

However, if the criticized government responded with effective whataboutism, respondents were 16 percent more likely (compared with the no-comment case) to view US government actions cynically, as another example of US hypocrisy (Figure 6d). “The US government at present become a do what meets the govt agenda country instead of a lead by example country,” wrote one respondent. Another wrote, “I don't think it is ok to tell another country to stop doing something our country is also doing. Lead by example.” Here, exposure to whataboutism shifts the respondents’ focus from human rights abuses to questioning US intentions. Collectively, these comments complement our earlier causal mediation analysis of how whataboutism affects public approval of American foreign policy through attitudes to US credibility, legitimacy, and moral superiority.

Given the similar findings, the inductive approach of STM complements the more structured causal mediation analysis. The patterns uncovered with STM are consistent with our theoretical priors regarding how whataboutism affects public support for US foreign policy through US credibility and rhetorical coercion. Moreover, these comments suggest that whataboutism shapes the narrative behind US foreign policy by shifting the framing of the US from moral arbiter in the international arena to just another powerful state hypocritically pursuing its own agenda.

US Rejoinders on Whataboutism

These findings leave a crucial question unanswered. In the earlier design, the US government did not have an opportunity to respond to whataboutism—which could have significantly reduced or eliminated its effectiveness, as Americans are likely to trust their own government over foreign governments.Footnote 78 To address this shortcoming, in January 2022 we fielded an additional survey experiment with 3,200 US adult citizens through Lucid Marketplace.

In the follow-up experiment, we replicate the results of the main survey, which should strengthen the external validity of our results given that this happened in a different time period.Footnote 79 But in these new scenarios we allow the US government to counter the whataboutist narrative. We based our possible responses on four common American counter-narratives. The first is outright dismissal of whataboutism as a distraction; this should weaken the whataboutist charge by painting it as an unjustified form of topic shifting.Footnote 80

A second possible US government rejoinder is to acknowledge responsibility for the misdeed but also claim that, unlike the whataboutist foreign government, the US government has effectively addressed this problem. A common strategy used by supporters of American exceptionalism to address “inconvenient” yet morally reprehensible facts such as slavery and the internment of Japanese Americans is to claim that steady improvements have been made since then. An important aspect of American exceptionalism is the supposed willingness of the US government (unlike other countries) to acknowledge its mistakes and act to fix them. Louis Hartz, a prominent scholar of American exceptionalism, notes that the US believes both that it was born perfect and that it has continuously improved.Footnote 81 Leveraging American exceptionalism, the US government could point to clear moral differences between the US and the whataboutist actor to restore US credibility and legitimacy.Footnote 82

The third rhetorical response varies with the issue area. For the election interference vignette, the US government tries to weaken the similarity between the acts by imputing different motives to the actors. If the US has “purer” motives, the two actions, though similar on the surface, may not be really comparable. Thus, the US can say that its foreign electoral interventions, unlike those of the whataboutist actor, were for the purpose of promoting and protecting democracy. This rejoinder is modeled after responses by sitting and former US government officials to Putin's use of whataboutism regarding Russia's intervention in the 2016 US elections.Footnote 83

For the refugee crisis vignette, the response focuses on the wider context. Here, the US government tries to de-emphasize its past misdeeds by emphasizing its “nicer” actions in related areas. It describes a pattern of proper behavior on this issue, which casts its misdeeds as aberrations. So we have the US government spokesperson saying that the US has provided more humanitarian assistance than any other country—accepting, for example, over 3.3 million refugees for permanent resettlement since 1975. This response is inspired by recent US government statements on refugee policy; referencing such statistics is common in such official statements.Footnote 84

The follow-up study replicates the results of the main survey, with similar marginal differences in mean approval of US behavior and support for sanctions between recent whataboutism and “no comment” responses.Footnote 85 The effectiveness of the US rejoinders in reducing the impact of whataboutism on public support for US foreign policy is limited but varies by issue area. Figure 7 splits the analysis by issue area: election interference or refugee crisis.

Figure 7. Impact of various US rejoinders to whataboutism on approval of US behavior

In the follow-up survey, we find that the US rejoinders failed to blunt the negative effects of whataboutism. There was no statistical difference between the various responses and no response. But in the refugee-crisis scenario, the wider-context and admission-of-guilt rejoinders reduced the effect of whataboutism by eight and eleven points, respectively.Footnote 86 We also managed to find point estimates with similar differences between the no-comment and recent whataboutism treatments, suggesting that these results are consistent across the two periods, even with large shifts in public perceptions on Russia.Footnote 87

Figure 8 repeats the analysis for support for the imposition of sanctions. In the election-interference scenario, there is no significant difference between the various responses and no response. In contrast, in the refugee-crisis scenario, the wider-context and admission-of-guilt rejoinders strongly reduce whataboutism's effect.

Figure 8. Impact of various US rejoinders to whataboutism on support for sanctions

Together, these results show that the rhetorical effects of whataboutism are robust to rejoinders by the target government. They are not an artifact of a research design that excludes “real-life” narrative contentions. Moreover, the effectiveness of rejoinders varies by their content and by issue area. Americans appear more open to counter-narratives that involve human rights rather than national security. This could be related to the US government's somewhat stronger baseline credibility among Americans vis-à-vis other countries in the human rights issue area. Even there, however, whataboutism continues to influence public opinion on US foreign policy.

Conclusion

Despite the widespread use of whataboutism by numerous countries on the international stage, little research has systematically investigated its effects. In this paper we present clear evidence that whataboutism significantly mitigates the negative consequences of international criticism. In our survey experiments, whataboutist narratives that focus on similar misdeeds by the American government reduce public approval of US criticism and future punitive actions such as economic sanctions by eighteen and ten points, respectively (supporting H1). However, these effects diminish when the US misdeeds being cited are more temporally distant (supporting H3). They become even smaller, and lose statistical robustness, when referencing an unrelated US misdeed (supporting H2).

Contrary to our expectations, there is little evidence that the identity of the country raising the whataboutist objections matters (H4), suggesting that both friends and adversaries of the US could use whataboutism effectively. In general, whataboutism appears to be effective on a range of possible international issues, from national security to normative and human rights issues. Furthermore, in many cases the effects of whataboutism are robust to various plausible rejoinders by US government representatives. The fears of past and present US officials regarding the use of whataboutism against the American government appear well founded, given this rhetorical tool's potential effects on the American public.

These findings provide the first strong empirical evidence that whataboutism can matter internationally. They show another way hypocrisy harms major powers, enlarging the growing literature on hypocrisy costs in international relations.Footnote 88 They also indirectly show that “name and shame” strategies do affect public opinion. However, they illustrate a key scope condition: the shaming actor (or the countries of its main funders or membership) must not be guilty of similar misdeeds that its target can exploit.Footnote 89 This study adds evidence that public diplomacy, even in some of its less benign forms, shapes public opinion. It provides first-of-its-kind empirical evidence that even negatively viewed regimes like Russia can use some forms of costless public messaging to influence foreign publics.

Whataboutism, however, does have limitations as a rhetorical tool. Americans, for example, appear willing to permit their government to criticize other countries’ behavior as long as the counter-criticisms are not directly related to the specific issue under critique by the US. These effects are also significantly weaker for related-but-older misdeeds, indicating that the US can escape the ghosts of the past, at least to some extent. Furthermore, in some issue areas, such as human rights, the effects of whataboutism can be blunted by providing evidence of attempts to deal positively with the relevant misdeeds. This means that, over time, improved conduct by the US government on the issues in question, at home and abroad, can reduce the efficacy of whataboutism used against it.

Future research on this understudied topic could examine other ways in which whataboutism affects public opinion in a variety of contexts. For example, do whataboutist campaigns also influence the publics of third countries “listening in” on such exchanges? Research on this topic can flesh out the myriad ways that whataboutism affects public opinion on foreign policy. Moreover, examining the effects of whataboutism in non-Western publics, with very different cultures, will be of significant value in assessing the potential potency of this tool.

Data Availability Statement

Replication files for this article may be found at <https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/M3ZPRD>.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this article is available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S002081832400002X>.

Acknowledgments

Author names are listed alphabetically. However, equal authorship is implied. We are grateful to Yusaku Horiuchi, Atsushi Tago, Alex Downes, Koji Kagotani, Erik A. Gartze, and Benjamin Goldsmith for their insightful feedback and support. We also appreciate the helpful comments from editors and reviewers at International Organization. In addition, we thank all participants of the Fall 2021 Pacific International Politics Speaker Series, the Security Policy Workshop at the Institute for Security and Conflict Studies, Elliott School of International Affairs at George Washington University, and our International Studies Association panel at the 2022 ISA conference, in which earlier versions of this manuscript were presented. Their valuable feedback was instrumental in shaping and improving this work.