Introduction

Interest in the history of the consumer cooperative movement has grown. For many years labour historians concentrated on conflicts that arose in the sphere of production, and tended to be quite dismissive of the cooperative movement, which they regarded as being devoid of ideological aspirations and thus undermining class consciousness.Footnote 1 The growth of interest in the history of consumption and consumer politics since the late 1980s has led to a reassessment of cooperative history. Peter Gurney's influential study of British consumer cooperation portrayed a movement with its own distinctive ideology and culture, which was able to present an alternative to mass capitalist consumption during the second half of the nineteenth century and first half of the twentieth.Footnote 2 Similarly, Ellen Furlough examined the development of the French cooperative movement over a century in the context of the history of French retailing and consumerism, while Peder Aléx's history of the Swedish cooperative union, Kooperativa Förbundet (KF), focused on the cooperatives’ role in promoting “rational consumption” among the citizens of the emerging Swedish welfare state.Footnote 3 Of particular interest has been the role of cooperation in mobilizing consumerist interest among working-class housewives, especially during World War I, and the Women's Cooperative Guild has been acknowledged as one of the most radical and influential working-class women's organizations in early twentieth-century Britain, for example.Footnote 4

This insistence on the need to understand cooperation on its own terms is undoubtedly welcome, but even so there is still a tendency for cooperative history to be regarded rather pessimistically. As Lawrence Black and Nicole Robertson point out in the introduction to their recent anthology on the British cooperative movement, this is in part related to the decline of the movement in Britain – and indeed in many other European countries – during the second half of the twentieth century.Footnote 5 Matthew Hilton has suggested that, in Britain at least, cooperation, rather than challenging the dominant capitalist mode of consumption, could instead be seen as the consumerist alternative to capitalism that was never fully realized. The movement's continued adherence to free trade after 1918, and its unwillingness to negotiate with the state, undermined the possibility of constructing a coherent consumerist politics. After 1945, the movement failed to adapt from a prewar “politics of necessity” and embrace the new era of mass consumption; it came to be regarded as old-fashioned, drab, and increasingly irrelevant.Footnote 6 By the 1980s, concerns about the continued viability of established consumer cooperatives were being echoed across Europe.Footnote 7

The cooperative movement was undoubtedly one of the most important social movements in Europe during the first half of the twentieth century. By 1940, membership of the British consumers’ cooperative movement, the largest in Europe, amounted to over 8.7 million.Footnote 8 Given that often one household member joined on behalf of an entire family, the reach of cooperation was even greater than this suggests: in France it has been estimated that 9 million individuals, or 22 per cent of the population, had some connection with cooperation by the late 1920s.Footnote 9 For millions of people throughout Europe, the consumers’ cooperative movement was a ubiquitous part of everyday life and the main supplier of such essential provisions as bread, coffee, tea, sugar, and potatoes.

It was, moreover, a truly transnational movement that from 1895 had its own international organization, the International Cooperative Alliance (ICA). Established initially through the collaborative efforts of French and British cooperators, by the 1930s the ICA had become an extensive organization claiming to represent the interests of 100 million cooperators in Europe, the Americas, Asia, and beyond.Footnote 10 As its historian Rita Rhodes has commented, the ICA was a remarkable institution, not least in that it was the only one of the pre-1914 international organizations in which the USSR remained a member after 1917, and it deserves to be considered alongside the other great organizations of interwar internationalism such as the ILO, the League of Nations, and the IFTU.Footnote 11 Surprisingly, however, historians have paid scant attention to the cooperative movement from a transnational perspective. Only a handful of scholars has examined cooperation in more than one country, and there are even fewer detailed studies of cooperative internationalism and the ICA.Footnote 12

This article considers the meaning and practice of cooperative internationalism in the ICA during the interwar period, in the context of the many crises that beset the Alliance during this period. From its foundation in 1895 the ICA wrestled with the question “What is cooperation?”. Was it simply a means to promote the efficient distribution of goods, or did it have a wider ideological ambition? These debates, though internal to the ICA, are of wider historical interest for three reasons.

Firstly, an examination of cooperative theory and practice may help to illuminate the transnational aspects of consumerism and consumer politics in the interwar period.Footnote 13 Many cooperators were liberal internationalists who were motivated by the conviction that the application of cooperative principles to international relations would help to secure peace.Footnote 14 Economic historians have pointed out that the “first era of globalization” did not come abruptly to an end in 1914; rather, the experiences of food shortages and rationing during World War I heightened consumers’ awareness of international networks of distribution and supply, and meant that European governments “looked towards international mechanisms of co-ordinating food, of eliminating cycles, and of stabilizing markets”.Footnote 15 Although cooperators continued to defend free trade after 1918, they also contemplated a radical reorganization of trade based on cooperative principles.Footnote 16 An International Cooperative Wholesale Society was established to promote joint cooperative trade among ICA national members, but this ambition proved harder to realize in practice, partly because of the difficulties in reconciling different national interests.Footnote 17

Secondly, as Frank Trentmann has noted, analysis of these debates calls for a more integrated and plural approach to the history of consumption, which acknowledges the growing realization of the mutual and interdependent interests of consumers and producers in the wake of the economic crisis of the early 1930s.Footnote 18 The early years of the ICA were dominated by struggles between the mainly French advocates of co-partnership or profit-sharing cooperative production, and British supporters of consumer cooperation.Footnote 19 The financial dominance of the British Cooperative Union resulted in a partial victory for consumer cooperation, strengthened further when the representatives of the German agricultural credit unions withdrew from the Alliance in 1904, and by the local political struggles over the control of the food supply during World War I.Footnote 20 But it was only ever a partial victory. While there were many who would have gladly seen the ICA as a consumers’ international, and also those, as in Belgium for example, who went even further in regarding consumers’ cooperation as the “third pillar” of the socialist labour movement, there were others, like the representatives of farmers’ cooperatives in Denmark and Finland, who insisted on a broader and more inclusive vision of the cooperative movement. This question became more acute as the Alliance began to expand beyond Europe during the 1920s to include producers’ associations in Asia and the Americas.

Thirdly, it is suggested that an examination of the ICA's internal debates during the 1920s and 1930s can help to shed important light on the ambitions, limits, and practices of internationalism during the interwar period. The Alliance's triennial congresses had largely ceased to be a forum for the transaction of business in the interwar period, and were instead an opportunity to celebrate and show off cooperative achievements to a succession of major European cities: “a public relations performance of internationalism” similar to that which Kevin Callahan has researched in the context of the Second International.Footnote 21 The ICA's main decision-making organs were instead the Central Committee, in which all national members were represented, and the Executive Committee, composed to reflect the most important national interests that made up the Alliance.Footnote 22 Moreover, examination of the operations of these committees supports the evidence from other international organizations that internationalist rhetoric did not necessarily transcend national interests, but instead often reinforced them.Footnote 23

The rather fraught debates of the early 1930s over the cooperative response to political and economic crises exposed the national divisions within the ICA. On the one hand, a “social democratic” bloc, including Austria, Czechoslovakia, Belgium, and to some extent Britain, urged political involvement in the major issues of the day, including peace and disarmament, and was outspoken in its opposition to fascism. Their views also found sympathy in the International Women's Cooperative Guild, led by the Austrian Emmy Freundlich, which was becoming increasingly militant in its advocacy of cooperative engagement with political issues such as peace.Footnote 24 Opposed to this position was a group including all the Nordic countries, and to some extent Switzerland, that was prepared to make its collective voice heard in defence of a more pragmatic position, and argued for a concentration on purely “cooperative” matters. The British delegates supported the Nordic position on some matters such as the response to Nazism, but were concerned above all to defend the interests of their movement as the largest and most influential member of the Alliance, and were particularly uneasy about any initiatives which threatened to harm the predominance of the English Cooperative Wholesale Society (CWS) in international cooperative trade.

This article is concerned in particular with the emergence of a Nordic bloc as a distinctive grouping within the Alliance. There are several reasons why the Nordic region is of interest in this respect. Firstly, the strength of the region's cooperative movements was widely acknowledged. Measured in terms of annual trade, the Danish and Swedish central cooperative wholesale societies were ranked sixth and seventh respectively among the members of the ICA in 1924, with the two Finnish wholesalers together accounting for a similar amount.Footnote 25 Secondly, the region produced several influential cooperators, including the Swedes, Anders Örne and Albin Johansson, and the Finn, Väinö Tanner. All three men made influential contributions to international cooperative thinking during the interwar period, and Tanner was elected as President of the ICA from 1927. Thirdly, despite its semblance of unity on the international stage, cooperation in the Nordic region was actually rather diverse, ranging from the agricultural cooperatives of rural Denmark and Finland, to the strongly consumerist federation in Sweden. In both Denmark and Finland, moreover, the national consumers’ cooperative movement was split along socio-ideological lines. The existence of a common regional position cannot be taken for granted therefore but must be approached from a transnational perspective, in order to understand how it was shaped by the dynamics of national, regional (intra-Nordic), and international (ICA) relationships. An exploration of Nordic interests and actions in the sphere of cooperation may also help to shed some light on the emergence of the Nordic region within the international sphere more generally in this period.Footnote 26

The article begins with a discussion of the ideological debates in the ICA during the 1920s and 1930s, focusing on the inquiry into the Rochdale Principles as an attempt to establish a coherent programme for the Alliance. The paper then turns to explore the Nordic contributions to this debate, based on the defence of cooperative political neutrality. Given the diversity of the cooperative movement in the region, the emergence of a common Nordic position cannot be taken for granted, but must be explained in relation both to national currents and international perceptions of the region. Particular attention is paid to the Nordic cooperators’ insistence on the practical, business side of the movement, which, it is suggested, nonetheless contained within it a vision for the transformation of capitalist consumption. A final section of the article considers the implications of these cooperative “moral economies” for the ordinary men and women who shopped at the cooperative store.

Cooperative ideology in the ICA: the debate on the Rochdale principles

The ICA faced a number of serious challenges as it resumed its activities after the interruption of World War I. In the first place, cooperative societies could not escape the economic difficulties of the period: the disruption to trade and difficulties in securing supplies in the immediate postwar years; the hyperinflation in central Europe and the instability of the foreign exchanges; and, later in the decade, the rise of economic protectionism. As the 1920s progressed, it became increasingly clear that there would be no return to the economic liberalism of the pre-1914 era, and that cooperatives would have to adapt to new circumstances including the rise of monopoly capitalism and state trading. Secondly, the post-1918 years saw the emergence of new international and intergovernmental organizations such as the League of Nations and the International Labour Organization, and it was not clear how the cooperative movement should respond to these. Thirdly, and most importantly, the Alliance found its unity threatened by the rise of political extremism on both the left and the right. The decision to allow the Soviet cooperative organization Centrosojus to remain a member of the ICA was largely due to the enthusiastic support of the British cooperators, who, as Kevin Morgan has suggested, saw mirrored in Bolshevism their own aspirations to create a new economic order.Footnote 27 However, the revolutionary agitation of the Soviet delegates within the Alliance made their presence deeply controversial, and the decision was later openly regretted by one of its staunchest supporters, the General Secretary Henry May.Footnote 28

A major problem for the ICA, as it struggled to respond to these problems, was that it lacked a coherent programmatic statement of cooperative ideology. It did, however, possess a powerful foundational myth in the story of the Rochdale Pioneers, the consumer cooperative society founded in northern England in 1844. As several British cooperative historians have pointed out, the cooperative movement was imbued with a strong sense of its own past, celebrated and commemorated by local societies through the publication of jubilee histories. These histories served an important propaganda function, illustrating the movement's progress on the basis of its fundamental principles.Footnote 29 The celebration of the Rochdale Pioneers as the founding fathers of the modern cooperative movement was not just confined to Britain, but was widely practised internationally. The translations of texts by G.J. Holyoake, Beatrice Potter, and others were influential in disseminating the Rochdale system of cooperation elsewhere in Europe, its popularity cemented by the very public successes of the British movement.Footnote 30 Recognizing this, in 1931 the English Cooperative Wholesale Society (CWS) opened the original Toad Lane store in Rochdale as a museum, which acted as a site of pilgrimage for cooperators from both Britain and overseas.Footnote 31

In the interwar period, Rochdale was also a common reference point within the committees of the ICA, often used to legitimize current practices. Article 1 of the Alliance's rules referred to its work as being “in continuance of the work of the Rochdale Pioneers”. The French cooperator Ernst Poisson suggested that the Rochdale principles had “a sort of mystic appeal”, and a “religious glamour” for many cooperators.Footnote 32 Lecturing to the international cooperative school in 1932, Henry May also noted the quasi-religious appeal of the word “Rochdale”: “You cannot more grievously offend the Cooperators of any country than by charging them with ignorance of, or disloyalty to, the Rochdale Principles. They will acknowledge the most extraordinary divergences in their practice but still claim that their title is clear to a place in the apostolic succession.”Footnote 33 Rochdale held a powerful emotional appeal that completely eclipsed alternative cooperative models, such as the German Raiffeisen and Schulze-Delitsch societies.

The problem was that, however well the Rochdale idea functioned as a myth, it offered precious little by way of practical guidance to cooperative means and ends. In 1930 therefore, the ICA's Vienna Congress decided to conduct a formal inquiry into the meaning of Rochdale cooperation, with the aim of agreeing a definitive set of principles. The General Secretary produced an initial report including extensive citations from the original sources that were available, namely the Rochdale society's original rule book, its early minutes, and G.J. Holyoake's historical account of the society. Perhaps to add further authenticity to his memorandum, May also reported that he had visited the Toad Lane museum and interviewed both a former secretary of the society and the daughter of one of the original Pioneers.Footnote 34 The inquiry was thus not only an attempt to establish a cooperative programme for the future, but also an investigation of the movement's own history, and an attempt to lay definitive claim to the Rochdale legacy in order to prevent its being used for any other purpose.Footnote 35 The special committee appointed by the Executive agreed on six fundamental principles: open membership, democratic control, cash trading, surplus redistributed as a dividend on purchases, limited interest on capital, political and religious neutrality. A seventh principle, concerning the allocation of resources for education, was added a few months later, and the final report also noted two others – trading exclusively with members and voluntary cooperation – which were not part of the Pioneers’ original programme but were nonetheless felt to be “inherent in the cooperative idea”.Footnote 36

The committee's final report, presented to the ICA congress in 1934, noted that it was the clause on political and religious neutrality that had sparked the most discussion during the course of the inquiry.Footnote 37 The questionnaire on the Rochdale principles sent to all national organizations in 1932 confirmed the well-known divergences from strict neutrality, including Belgium, Austria, Britain, and part of the Danish movement.Footnote 38 Even so, it seemed that all members – with the exception of the USSR – would be prepared to accept the inclusion of political neutrality as one of the Rochdale principles. It was thus a bitter blow for the authors of the report when, in the debate on the report at the 1934 congress, the British delegation moved to reject the clauses on neutrality and cash trading.Footnote 39 They argued that the profound changes that had occurred since 1844 had led them to question cooperative non-alignment, and they objected to the imposition of neutrality as a moral obligation on national organizations, arguing instead that cooperators could be, as the Belgians had declared in 1924, “Socialist in their own country, but neutral in the ICA”.Footnote 40 The Swedish delegate Axel Gjöres defended the neutrality clause, and sought to rescue the report by proposing that the whole thing be referred back to the committee, an amendment which was accepted by the British.Footnote 41 A bitter row ensued as the matter was discussed in the Alliance's committees over the next two years, and there were some heated exchanges before a compromise could be reached, stating that the neutrality principle was considered to be important and desirable but not absolutely essential in defining a cooperative society.Footnote 42

The debate on political neutrality was sharpened by the Alliance's dilemma over how to respond to the rise of Nazism in Germany. Throughout the spring of 1933 the ICA's officers tried to keep an open mind on the German situation. Eventually they were reluctantly forced to conclude that the German cooperatives had lost their autonomous and voluntary character and they were expelled, but only after a series of fraught and lengthy meetings which threatened to split the Alliance disastrously.Footnote 43 The problem for cooperation was that, although most cooperators were instinctively anti-fascist, not all of them based this opposition on socialism, and there was nothing contained within any of the movement's ideological or programmatic statements to suggest that cooperators should necessarily oppose Nazism. The ICA had accepted the Soviet cooperative organization Centrosoyus in the name of political neutrality after all, so should it not treat the German cooperative movement the same way? For some, the answer to this dilemma was to base the exclusion of the Germans on a robust defence of cooperative principles, on the grounds that the German movement had abandoned its claims to be a voluntary movement in allowing itself to be taken over by the Nazi authorities.Footnote 44 Nonetheless, the troubling legacy of the Soviet presence remained. The Swede Anders Hedberg claimed to be speaking for all the Nordic countries when he acknowledged that the situation in Germany was “atrocious”, but added that:

[…] we remain cooperators and the danger at present is that we let ourselves be guided by political hatred towards events in Germany and neglect the cooperative side of the question […] we should maintain our political neutrality above all, and we should avoid laying ourselves open to blame for flirting with Russia while rejecting Germany.Footnote 45

The ICA survived both the loss of Germany and the continued membership of the USSR, and in 1934 was even able to claim some success when it intervened to maintain the autonomy of the Austrian cooperative movement following the civil war.Footnote 46 But the crises of the early 1930s had left it seriously divided. The representatives of the social democratic Austrian and Czechoslovak cooperative movements were the most consistently and outspokenly in favour of unequivocal German expulsion. Against them, the British and Swedish delegates urged pragmatism, arguing that the Alliance should accept the Germans’ appeals for non-intervention and wait until the situation had stabilized itself before taking a final decision.Footnote 47 The Alliance's French Vice President, Ernst Poisson, warned against allowing the ICA to become “an auxiliary of the Second International”, by associating itself with a socialist position, a possibility that was vigorously denied by those sympathetic to socialism.Footnote 48

Political neutrality and the emergence of a Nordic bloc

As this suggests, the Swedish delegates were among the staunchest defenders of the principle of cooperative political neutrality, and in 1936 they combined with the representatives of Denmark and Norway to submit a joint Nordic motion on political neutrality.Footnote 49 This was by no means a new position, however, but one which could be traced back to the early 1920s. The Finnish wholesale society SOK objected to an ICA statement agreed in 1919, on the grounds that it contained “several questions which are outside the actual cooperative programme”, while Danish cooperators were openly critical of the ICA's attempts to take a stand on international issues such as the occupation of the Ruhr and the reconstruction policy of the League of Nations.Footnote 50 They agreed with the Swedish cooperator Anders Örne that the ICA should concentrate on the exchange of statistics and technical information, and avoid becoming embroiled in a “general confusion of ideas and endeavours”, which had nothing to do with cooperation.Footnote 51 In 1931 the Danish and Swedish delegates opposed a Belgian resolution to the Central Committee on disarmament, pointing out that they were not opposed to peace itself, but insisting that cooperation was about the practicalities of business.Footnote 52 The unity of the Nordic position was also invoked when the Swede Anders Hedberg criticized the proposal that the ICA should present a resolution on economic policy to the World Economic Conference in 1933, suggesting that it would cause “unnecessary irritation” not only to cooperators in Sweden, but also to “several friends” in both Finland and Denmark, were the Alliance to intervene in matters that did not directly concern it.Footnote 53

Clearly concerned about the seriousness of these criticisms, the ICA's leadership went to some lengths to respond to them. A special meeting was convened with representatives of the organizations in question in the summer of 1925, but its outcome was inconclusive, and the matter refused to disappear.Footnote 54 By 1933 there was felt to be a very real danger that some of them would secede. The General Secretary made a short tour of the region in an attempt to mitigate the threat, but found that he was not allowed to attend the SOK congress, such was the depth of feeling against the ICA.Footnote 55 These concerns have to be seen against the background of the recent departure of Germany, and the knowledge that any further losses would seriously weaken the Alliance, possibly fatally. But it also suggests the extent to which the Nordic countries seem to have achieved a prominence that allowed them to constitute a powerful bloc within the ICA, despite their relatively small populations.

The emergence of a sense of regional solidarity should not be taken for granted, however, for it would be rather difficult to speak of “the cooperative movement” in the Nordic countries as a homogeneous whole. Rochdale was a common reference point, though influences from elsewhere, especially Germany, were also important.Footnote 56 In both Denmark and Finland it would be more accurate to speak of two forms of consumer cooperation: the mostly rural distributive societies affiliated to the wholesales FDB and SOK respectively, and the workers’ distributive societies in the towns.Footnote 57 In Finland, the movement had split into two factions in 1916, with the so-called “progressive” wing forming its own wholesale and central propaganda organizations, OTK and KK, while the “neutral” cooperative societies affiliated to SOK retained their ties to the agricultural movement through the Pellervo Society, a propagandist and educational organization established in 1899.Footnote 58 In Denmark, the equivalent central organization was Andelsudvalget, also founded in 1899, and, like Pellervo, including both agricultural and rural distributive societies in its remit, while from 1922, the workers’ cooperatives had their own central organization, Det kooperative Fællesforbund.Footnote 59 For this reason both Denmark and Finland had dual representation in the ICA: Denmark by both Andelsudvalget and Det kooperative Fællesforbund; Finland by SOK and its propaganda organization YOL on the one hand, and by the equivalent “progressive” organizations OTK and KK on the other.Footnote 60 The situation was somewhat different in Sweden and Norway. Here, the functions of propagandist and educational union on the one hand, and central wholesale for the distributive societies on the other, were combined in the same organizations, KF and NKL.Footnote 61 Both were organizations exclusively for consumer cooperatives, although recent research in Norway suggests that NKL had some success in promoting trading relations between agricultural and distributive cooperative societies, especially at the local level.Footnote 62

Given these differences, how can we explain the emergence of a Nordic bloc within the ICA? Some cooperators pointed towards the existence of a natural affinity between “neighbouring countries, speaking sister languages and thus obviating any difficulties in translation”, as the Dane Frederik Nielsen put it.Footnote 63 Certainly this may have helped to develop a sense of regional solidarity within the international forum of the ICA, at a time when even the most committed internationalists invariably tended to categorize individuals along racial lines.Footnote 64 Moreover, the practicalities of participation in international meetings were also influential.

The region's relative isolation and the long overland journeys which its cooperators were forced to make to attend ICA meetings helped to forge strong personal networks among a small group of cooperative leaders. Väinö Tanner's journey to ICA meetings in London via Stockholm, Hamburg, Vlissingen, and Harwich in 1929 lasted four days, including two nights on trains and one on the Turku–Stockholm ferry. But it was planned to include one full day in Stockholm, which presumably gave him the opportunity for meetings with his Swedish colleagues.Footnote 65 In an unpublished personal memoir of Tanner written towards the end of his life, Albin Johansson reminisced about the long hours they had spent together on car journeys travelling down to the continent for ICA meetings, and the opportunity this gave them to develop a close friendship.Footnote 66 Personal experiences also had some bearing on Nordic sympathies for the German position, as there was a legacy of strong contacts between the movements in Germany and the Nordic countries.Footnote 67 As young men, both Tanner and Johansson had studied and worked in the German consumer cooperatives, where they formed close relationships with the German cooperative leader Heinrich Kaufmann, and Kaufmann was later influential in securing Tanner's election as ICA president in 1927.Footnote 68

Secondly, it was perhaps also the diversity of the cooperative movement in the Nordic countries which strengthened its adherence to political neutrality as a common cause. Cooperation in the Nordic region was not only politically diverse but also socially heterogeneous, largely because of its rural character.Footnote 69 Although the distributive societies of large urban centres were important – and many, like Helsinki's Elanto, were proudly shown off to and greatly admired by foreign visitors – consumer cooperation throughout the region also had strong links to the countryside, embodied in the local village store.Footnote 70 Even in Finland, where the 1916 split reflected the same bitter social cleavages that were to flare up in the civil war two years later, the division between the two factions of cooperation was a complex one, and both cooperative organizations declared their determination to remain above politics.Footnote 71 In their writings and speeches, cooperators thus insisted on the need to see cooperation as a movement for all, regardless of political affiliation or social status.Footnote 72 Andelsudvalget saw itself as being especially important in this respect, for, as Axelsen Drejer put it, “there is scarcely anywhere else where people of different social classes are united in cooperative societies to the extent that they are here in this country”.Footnote 73 Perhaps more surprisingly, similar views were also expressed by the more explicitly consumerist organizations, such as Swedish KF and Finnish KK. The authors of a KK proposal for an international cooperative economic policy circulated to the ICA in 1931 pointed out that from its beginnings cooperation had appealed to “a wide cross-section of the population”, uniting the interests of “the working class and the poorer farmers”.Footnote 74 Its most important future task would be to help promote a more rational and conflict-free organization of economic life, and an acceptable division of labour between agricultural and consumer cooperation.Footnote 75

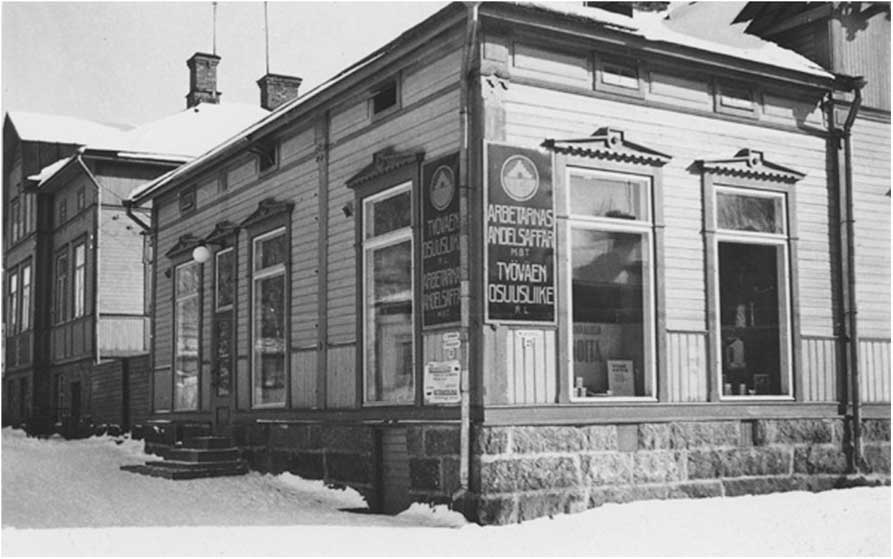

Figure 1 Local cooperative store of the Vaasa Region Cooperative Society, Finland, 1930. In 1916 the Finnish consumer cooperative movement split into two factions, each with its own wholesale society. Although the sign on this store says it is the “Workers’ Cooperative Store”, both sides of the movement remained politically unaligned. Finnish Labour Archives, Helsinki. Used with permission.

Thirdly, it is possible that political and social conflicts in the retailing sector were more muted in the Nordic countries than in other parts of interwar Europe. To be sure, the region was not immune from the class tensions and ideological divisions of the period.Footnote 76 As in many other parts of Europe, the food shortages of 1916–1918 led to widespread unrest in Sweden, for example, and to popular anger against small shopkeepers accused of profiteering.Footnote 77 But these tensions never gained the intensity they did in other parts of Europe during the interwar period. Jonathan Morris, writing about Italian shopkeepers, cautions against assuming unequivocal support for fascism among small shopkeepers, but there is no doubt that this group was becoming increasingly politicized across Europe as individuals faced commercial competition from both cooperatives and the new capitalist chain stores.Footnote 78 An ICA report in 1933 found that the cooperative movement was under threat of being drawn into direct conflicts in France, Czechoslovakia, Britain, Yugoslavia, and most seriously Austria, to say nothing of the recent incorporation of the German cooperatives into the Nazi state.Footnote 79 But the report also noted how calm the situation was in northern Europe. Good progress was reported in Denmark and Norway, and in neither Finland nor Sweden was cooperation felt to be under serious threat from the attacks of private traders.Footnote 80

The Nordic vision of cooperation

Despite their many differences, the representatives of the Nordic cooperative movements thus sought to present a united front to the ICA in their defence of the political neutrality of cooperation. In particular, the leadership of Swedish KF took the initiative in establishing this as a common platform. As Peder Aléx has pointed out, one of the first attempts to condense the Rochdale legacy into seven basic principles was made by the Swede Anders Örne, in a paper delivered to the international cooperative congress in Basle in 1921. As the ICA's historian W.P. Watkins noted, the paper, which drew on internal debates within KF, could be regarded as one of the first major Scandinavian contributions to international cooperative thought.Footnote 81 Such was its importance that Örne's subsequent book on cooperation was translated into English and published by the CWS in 1926.Footnote 82

What is striking about Örne's statement is the practical, even prosaic nature of his seven principles. This was no grand vision of the future cooperative commonwealth, but rather a practical guide to how to organize a cooperative business. The central Rochdalian idea of distributing the surplus in the form of a dividend on purchase was present, as were the commitments to democratic organization (one member, one vote) and to education, but in his other points Örne was even more practical, specifying, for example, the need for cooperative societies to deliver unadulterated goods, to use fair measures, and to sell at market price.Footnote 83 Indeed, Örne acknowledged that those new to the movement might be struck by the “meagreness’ ”(torflighet) of the seven principles, but he was nonetheless convinced that, if followed conscientiously, they contained within them the basis for a new economic order.Footnote 84

Örne's insistence that cooperation should be regarded not as a social movement, but as an economic enterprise, went to the heart of debates about the meaning of cooperation during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.Footnote 85 His argument bears some resemblance to the conception of the “Cooperative Republic” associated with French cooperators of the “Nîmes school” and in particular Charles Gide, who led efforts to revive the International Cooperative Alliance after the war.Footnote 86 From 1895, the French movement had been formally split between those who subscribed to this view of cooperation, and those who preferred to see cooperation as the “third pillar” of the working-class movement, directly aligned with the socialist party. The reunification of the two wings in 1912 has been interpreted by Ellen Furlough as a defeat for the socialist vision of cooperation as part of the working-class struggle against capitalism, and a victory for the reformist strand of French cooperation, which during the 1920s seemed more inclined to adopt the strategies of capitalist commerce than to oppose them.Footnote 87

To be sure, the paper presented to the ICA's 1927 congress by Örne's KF colleague, Albin Johansson, seems to support this view, with its emphasis on the need for rational business organization and the acknowledgement of the importance of advertising. Johansson even called into question the wisdom of allowing members direct democratic control, arguing that cooperatives were best served by the leadership of professional “experts”.Footnote 88 Nonetheless, both Örne and Johansson continued to insist on the fundamental difference between cooperation and private trade. This distinction was implicit in cooperation's redistribution of the surplus through the dividend, the democratic accountability of its management, and the strictly limited interest paid on the share capital held by individual members, as well as in its promotion of “rational” consumption through the types of goods supplied and the avoidance of credit.Footnote 89 Cooperation's idealism thus lay, not in some utopian vision of the future, but in the practicalities of its internal organization, which nonetheless contained within it the means to promote fundamental economic and social change.Footnote 90

The emerging strength of the Nordic region within the International Cooperative Alliance must also be seen in the light of the wider reputation Nordic cooperation came to enjoy internationally. The Danish agricultural cooperatives attracted much favourable international attention during the early twentieth century. Their products and methods were exhibited at the Paris exhibition in 1900, and they were cited with approval in a number of international studies of agricultural modernization.Footnote 91 Denmark, where “cooperation pervades everything”, was “quite the most valuable political exhibit in the modern world”, wrote the American, Frederic C. Howe, in 1921, and should be visited by agricultural commissions.Footnote 92 The Danish cooperator, A. Axelsen Drejer, was well aware of this, and an internal memoir written by him in 1926–1927 reveals a strong consciousness of the international significance of Danish cooperation, and an almost missionary zeal to promote this as being of wider benefit to the world.Footnote 93 As the members of Andelsudvalget were aware, however, this reputation had to be protected. If Danish cooperators were to engage in political debates, wrote Anders Nielsen, then “the incense which now from abroad […] is burned to the so-called exemplary Danish Cooperative undertakings, would come to an end”.Footnote 94

Of particular interest to the ICA was the Danish success in uniting the interests of consumer and producer cooperatives under the auspices of Andelsudvalget. The question of intra-cooperative relations was discussed at successive international cooperative congresses throughout the 1920s, as the Alliance sought to find ways, in the words of Albert Thomas, to “lay a strong foundation for a world economic system in which the spirit of strife and competition would have no place”.Footnote 95 It gained new urgency from the end of the 1920s, for several reasons. Firstly, the League of Nations, at its World Economic Conference in 1927, had also recognized this problem, and had recommended the establishment of a joint committee on relations between agricultural and consumer cooperatives, but this failed to materialize. In 1929, worrying rumours emerged about the foundation of a new International Federation of Agricultural Cooperation, which presented a potential threat to the ICA. The Alliance took matters into its own hands, and established a joint committee under the chairmanship of the French cooperator and ILO president Albert Thomas, though he died prematurely before the committee could achieve any concrete results.Footnote 96 Secondly, the ICA was at the same time considering new applications for membership from cooperative organizations engaged in agricultural production outside Europe. The General Secretary's tour of North America in 1930 led directly to the admission of the Canadian Wheat Pools from the western prairies, and the Alliance also contemplated “missionary journeys” to recruit new members even further afield in Asia and South America.Footnote 97

These decisions had their detractors who argued that the Alliance was and should remain principally for consumer cooperatives.Footnote 98 But for many others, the Danish cooperative movement could stand as a practical example of the success of the cooperative aspiration to overcome class tensions and address the “disequilibrium between the forces of consumption and production”, in the words of the French cooperator Ernst Poisson.Footnote 99 In 1928, Drejer was invited to address the International Cooperative School on the question of consumer–agricultural cooperative relations, for, as Henry May put it, “the Danish Cooperators have a story to tell which is peculiar to their own country”.Footnote 100

By the 1930s, international attention shifted towards Sweden and KF, which was famously lauded by the American journalist Marquis Childs in his 1936 bestseller, Sweden: The Middle Way.Footnote 101 The Nordic cooperative movements also attracted the attention of the Roosevelt Commission established by the US President to examine cooperative enterprises in Europe.Footnote 102 Childs commented approvingly on the pragmatism of Swedish cooperation, which, he said, “is very little concerned with short cuts to Utopia. Interest and energy and will are concentrated on the cost of bread and galoshes and housing and automobile tires and insurance and electricity […] a system based on production for use rather than profit.”Footnote 103 Of particular interest was KF's success in its campaigns against the emerging villains of the 1920s and 1930s: the trusts and cartels of monopoly capitalism.Footnote 104 In 1926, Anders Örne told the Central Committee that the only way for cooperators to counter monopoly capitalism effectively was “to establish truly international cooperative enterprises of sufficient size and strength to enable them to enter into effective competition”.Footnote 105 By the 1930s, the Swedish cooperators could point to some tangible successes in this field, such as their “Luma” factory for the manufacture of light bulbs which had succeeded in forcing a cartel to reduce its prices.Footnote 106 KF also pressed the ICA to take further action in this area by establishing an international bureau for statistics on monopolies, which they even offered to fund.Footnote 107

The Nordic region also attracted attention for its efforts to promote international trade through the Nordisk Andelsforbund (NAF, or to give it the English title used within the ICA, the Scandinavian Cooperative Wholesale Society). Founded in 1918, NAF acted as a central purchasing agency for the central wholesale societies of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, and rapidly established itself as a major purchaser of certain overseas goods, such as coffee and dried fruit.Footnote 108 As Alexander Nützenadel and Frank Trentmann have pointed out, the experience of food shortages during the war had made Europeans “painfully aware” of their dependence on food imports, and the long and complicated chains of supply that lay behind them.Footnote 109 The foundation of NAF was a direct response to these difficulties; a pragmatic arrangement intended to give the Nordic cooperative wholesales greater leverage in the disrupted international markets of the immediate postwar era. But by negotiating directly with overseas producers NAF also sought to free cooperative supply from the control of capitalist import agencies, and, as its director Frederik Nielsen put it, “to carry the cooperative line beyond the oceans, making the goods pass through the consumers’ organization from place of production until delivered to the consumer”.Footnote 110

ICA debates on international trade in the immediate postwar era were mostly concerned with schemes to promote trade between the cooperative societies of different countries. The main aim of the International Cooperative Wholesale Society (ICWS), when it was formally established in 1924, was thus not to undertake trading itself, but to promote the exchange of trade information between members.Footnote 111 But it quickly became apparent that intra-European trade could account for only a small proportion of the needs of consumer cooperative societies. In 1922–1923 it was reported that over 70 per cent of cooperative trade was with non-European countries, and that over two-thirds of this was accounted for by just six commodities, namely wheat, bacon and lard, butter, sugar, coffee, and rice.Footnote 112 The committee turned its attention instead to joint import arrangements, and the NAF rules were translated and circulated as a model example of how such a scheme could be realized.Footnote 113 Albin Johansson was a particularly eager advocate of this, even to the extent of offering to commit KF to bearing any losses incurred as the result of a trial scheme for purchasing coffee through the NAF suppliers.Footnote 114 But his proposals for an international import agency could not be reconciled with the national interests of the large wholesales. The German and French representatives pointed out that fluctuations in exchange rates meant that they could purchase coffee more cheaply on local markets, and an even greater obstacle was the powerful English CWS, which was quite unwilling to contemplate disrupting its existing trading contacts.Footnote 115 In the end, all these proposals were overtaken by the outbreak of war in 1939, and came to very little. NAF stood alone as the one major achievement in international cooperative trading during the inter-war period.

Visions and realities

Hitherto, this paper has concentrated on the debates and actions of a relatively small group of cooperative leaders, most of whom it may be assumed knew each other personally. Public statements to ICA's meetings and congresses were, of course, the outcome of internal debates within the organizations concerned, which cannot be considered in any detail here, and they were also reported to a national readership through the cooperative press. Moreover, even the most prominent Nordic cooperators considered here could draw on extensive personal experience of the day-to-day management of large retail societies. Väinö Tanner had managed a cooperative society in Turku before he moved to Helsinki's Elanto in 1915. Albin Johansson began his retailing career as an errand boy before becoming the manager of Tanto cooperative society in Stockholm at the age of nineteen.Footnote 116 As Johann Brazda and Robert Schediwy have commented, Johansson – and indeed Tanner – may be regarded as typical of a new group of professional, technocratic cooperative managers who dominated some European organizations after 1918.Footnote 117

Johansson in particular insisted on the need to justify all cooperative initiatives in terms of the interests of consumers.Footnote 118 It is, however, notoriously difficult to uncover the meanings that debates about international capitalism and trade had for the consumers that shopped at the cooperative stores in Sweden and elsewhere. Most research emphasizes the very local nature of the connections between cooperation and consumers. Peter Gurney's research has shown how shopping at the local cooperative store – and in particular collecting the quarterly “divi” – was central to the constitution of an alternative cooperative culture in the working-class neighbourhoods of northern England.Footnote 119 In Ghent, the famous Vooruit cooperative made conscious efforts to create a “social democratic world of consumption”, in Peter Scholliers's words, through its provision of groceries and many other services, though it was also sometimes criticized for the commercialism of its activities.Footnote 120 According to Carl Strikwerda, this vision of an alternative cooperative economy lasted until well into the interwar period, until the collapse of the Labour Bank in 1934.Footnote 121

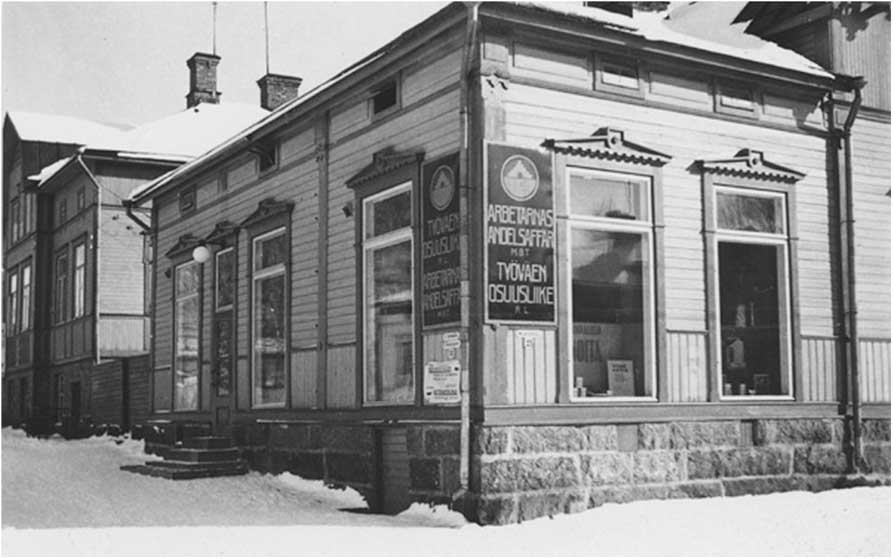

Figure 2 Interior of a cooperative store run by the Pielinen Cooperative Society in eastern Finland, 1910. Throughout the Nordic countries the village cooperative store was an important feature of rural life. Finnish Labour Archives, Helsinki. Used with permission.

Cooperation certainly seems to have had a strong visible presence in the Nordic countries, perhaps because of its largely rural character. Visitors to Finland in particular were impressed with the cooperative stores they encountered in prominent positions in the villages and small towns, as well as with the imposing buildings of the Elanto cooperative in Helsinki, and of the headquarters and factories of both wholesales.Footnote 122 The American traveller Agnes Rothery wrote in 1936, “There never was such a country of cooperators! […] The entire social fabric is permeated with cooperative societies.”Footnote 123 In Norway, developments in the provision of new services such as banking and insurance meant that by the end of the 1930s members could live most of their lives in the embrace of the local cooperative, especially in the rural areas.Footnote 124 In one of the few detailed local studies of cooperation in the Nordic region, Katarina Friberg has shown how shopping at the local store and receiving the dividend was also the main experience of cooperation for members of the large urban Solidar cooperative in Malmö, though her comparison with Newcastle-upon-Tyne also shows that there was less scope for members to participate directly in the management of the society in Sweden than there was in Britain.Footnote 125

It is even harder to judge the impact of international debates on cooperative members, although it should by no means be assumed that international consciousness was absent at the local level. Although ordinary consumers may not have thought about the cooperative organization of international trade that had delivered their goods every time they “opened the larder door”, as Gurney puts it, Frank Trentmann's research on the “buying for Empire” campaigns of the 1920s and 1930s shows that consumer consciousness could indeed be internationalist. Over a million British housewives joined the Women's Unionist Organization and became part of campaigns trying to connect metropolitan consumers with imperial producers.Footnote 126 In some countries, especially Britain, the Women's Cooperative Guild also developed an internationalist and pacifist consciousness during the interwar period, but this does not seem to have been influential in the Nordic region.Footnote 127 The women's guilds that were organized in KF, for example, partly inspired by British examples, rapidly became coopted into campaigns to promote the benefits of cooperation among non-members, and in this way cooperation tended to reinforce prevailing assumptions about gender roles.Footnote 128

Nonetheless, there were opportunities for the mostly male managers of local cooperative societies to participate in international activities. The ICA's triennial congresses presented opportunities for international travel and exchange, and the central federations often made the most of the long overland journeys by arranging for their delegations to make practical study tours of cooperative factories and facilities in other countries on their way to or from the congress.Footnote 129 The “cooperative spirit” was also fostered in other ways, such as the International Cooperative Days organized from the early 1920s, summer schools and camps, and production of films and literature. The Nordic Cooperative Festival in Stockholm in 1933 attracted over 47,000 people to an event which included singing and drama, a motor cavalcade through the city, and what was reported to be the largest firework display ever seen in the region.Footnote 130 The vast majority of those attending were Swedes, but there were speeches from representatives of all four nations, and the coverage in the cooperative press laid stress on the Nordic character of the meeting.

Delegates were also able to visit the newest and brightest jewel in the crown of Swedish and Nordic cooperation: the Luma light bulb factory. Luma was established as a deliberate attempt to break a Geneva-based international cartel in light bulb manufacture. It was organized as a consumer cooperative with the Nordic wholesale societies as its members, which meant that the factory, opened in 1931, was proudly described as “the first international factory in the Consumers’ Cooperative Movement”.Footnote 131 By July 1932 it was reported to be producing 15,000 bulbs daily, and to have forced the cartel to drop its prices by nearly 50 per cent.Footnote 132 Such was its success that it was even extended beyond the Nordic countries, when in 1939 KF opened a new factory in Glasgow, in partnership with the Scottish CWS.Footnote 133 “Luma light bulbs are now shining in every Nordic home”, declared the Norwegian journal Kooperatøren in its editorial.Footnote 134 This is doubtless an overstatement, but it is a powerful one nonetheless. Light bulbs offered a tangible, practical example of cooperative success in challenging international capitalism, visible to consumers through the drop in price. At the same time, they were a potent symbol of cooperation's status as a modern movement, and its ability to bring the benefits of new technology to all.

Conclusion

A recent book by Norbert Götz and Heidi Haggrén has shown the importance of Nordic participation in international organizations for Nordic region-building.Footnote 135 As founder members of the League of Nations (Finland joined in 1920), the Scandinavian states demonstrated a similarity of outlook and a willingness to engage in common initiatives. This, Götz suggests, was driven mostly by pragmatic concerns and shared beliefs in the common interests of small states, but also grew out of the regional efforts to promote Nordic cooperation in international relations.Footnote 136 Moreover, this internal sense of regional solidarity was also reflected in external perceptions of the Nordic countries as constituting a regional bloc: an “[e]ntente of the northern states”.Footnote 137 Kazimierz Musiał's study of the emergence of the “Scandinavian model” in the 1920s and 1930s notes how this model was formed at the intersection of what he calls “auto-” and “xeno-” stereotypes. In other words, the Scandinavian model was partly an external construction, lauded by foreign journalists and politicians, but it was also promoted internally by the Nordic governments themselves.Footnote 138 The same could also be said of the Nordic cooperative group and its reputation within the ICA: it was partly formed from within, but also developed in line with the expectations of other members. The Danish co-operators, in particular, seemed to be well aware of the reputation that they enjoyed abroad, and, as we have seen, Denmark was held up as a model example for how to overcome the antagonism between cooperative producers and consumers.

The presentation of both Denmark and Finland as model examples of socially inclusive cooperation belied the very deep divisions existing between the different branches of the movement in the domestic sphere. The Danish historian Claus Bjørn has described the difference between the rural andelsbevægelsen and urban kooperation in cultural terms: between the rural folk high school tradition and the labour movement, between the localism of the farmers and the centralization of the social democrats.Footnote 139 In Finland the difference between “neutral” and “progressive” mirrored to some extent the deep cultural and social cleavages that sparked the 1918 civil war, though it was far too complex to be reduced to a simple divide between farmers and workers, or even consumers and producers.Footnote 140 What was important, was that the International Cooperative Alliance seemed to provide a forum where these differences could be partially, even if not entirely, overcome.

The sources considered for this article are regrettably limited in what they can tell us about the informal contacts that were undoubtedly such an important part of these international gatherings: how and where delegates socialized, the languages they used to do this, the practical arrangements that were made to share travel and accommodation for delegates travelling long distances. But equally they do not contain any suggestion of animosity between organizations that, in the domestic context at least, were sometimes quite antagonistic to each other. On the contrary, the programmatic statements that emanated from leading cooperative writers in the Nordic region display a fairly remarkable degree of unity: on the rationality of cooperation as a system, on the need to concentrate on the practical matters of trade and management, and above all on the insistence on cooperation as a movement for all, regardless of political affiliation or social class.

Examination of the debates within the International Cooperative Alliance may help, as suggested in the introduction, to open up a broader and more integrated approach to the history of consumption, which acknowledges both the transnational and globalized politics of consumption in the interwar period, and the mutual interdependence of consumption and production. Cooperators were certainly well aware of these links, but their aspirations to reorganize international trade on cooperative lines proved much harder to realise in practice. The Danish movement might be held up as an example of the successful integration of consumer and producer interests, but there was also some resistance to the proposal to admit the Canadian Wheat Pools to membership of the Alliance in 1930, including from the Swedish representatives.Footnote 141 In the context of currency fluctuations and restrictive trade policies national interests were difficult to overcome, and acted as a brake on attempts to co-ordinate the import of so-called “colonial” goods between national wholesale societies.

Against the rather limited achievements of the ICWS, the Scandinavian Cooperative Wholesale Society (NAF) therefore stands out among attempts to promote international cooperative trade during the interwar period. With some justification, the directors of NAF could point to some success in their aspiration to “carry the cooperative line beyond the oceans”, and to secure imports of basic goods such as coffee and dried fruit to Nordic cooperative consumers. Although the initial aspirations for NAF ownership of plantations and production facilities abroad were not realized, the directors of the Nordic wholesale organizations saw in domestic cooperative production the means to resist the rise of international monopoly capitalism, and a notable success was the establishment of the Luma lamp factory in the early 1930s.

To return to the question raised in the introduction: was cooperation merely a scheme for practical shopkeeping, or did it also offer an aspiration for a new world, the so-called “cooperative commonwealth”? The Nordic cooperators were certainly, as we have seen, quick to emphasize their distaste for utopian schemes, and to concentrate instead on the practical and the everyday, arguing that the ICA should devote more time to the collection of statistics and exchange of technical information. For thousands of consumers the main experience of cooperation was undoubtedly shopping in the local cooperative store, and the leaders of Swedish KF in particular sought to justify their actions in terms of the practical benefits to consumers: the provision of essential goods at low prices. Moreover, in its very modernity the cooperative store could also offer its customers a promise of the future. The Finnish cooperative bakeries were “leading the way in the use of modern machinery”, wrote the Swede, Thorsten Odhe, while the Helsinki Elanto society's “present spacious and handsome shops […] contrast violently with the mean, dilapidated premises of the remaining private traders”.Footnote 142

It was also just in this practicality, it was argued, that cooperation contained the seeds of a new society. In the end, what held the ICA together and allowed it to survive the crises and divisions of the period was perhaps the very vagueness of the Rochdale legacy, condensed to a set of seven principles, which offered a straightforward programme for the management of a cooperative society but said very little about wider ideological aspirations. It is perhaps the paradox of cooperation that it united at once aspirations that were both vague to the point of meaninglessness – the generation of the “cooperative spirit”, promoting the reconciliation of opposing interests and faith in one's common human – and at the same time ultimately practical.