In 1950 the small agrarian village of Finsterwolde (population 3,250) in the north-east of the Netherlands gained a degree of notoriety in the United States, being attributed the epithet “Little Moscow”, when Time magazine reported on the dissolution of its communist-led municipal council.Footnote 1 In 1951 it shared this Cold War honour with the small French industrial town of Saint-Junien (population 10,645) in Limousin near Limoges, which figured in Life magazine as an example of the communist menace in France.Footnote 2 Described by Life magazine as a ville rouge, its most militant neighbourhood was also known as Petit Moscou.Footnote 3 Rural bastions in France too were named Petit Moscou or Petite Russie.Footnote 4 In Great Britain, the nickname “Little Moscow” was commonly used for small communist strongholds, mostly in a derogatory sense, as Stuart MacIntyre showed.Footnote 5

Both in Britain and Europe, communists themselves preferred to label this kind of locality “red”,Footnote 6 as in Seraing la Rouge in Belgium near Liège,Footnote 7Halluin la Rouge (also designated la Moscou du Nord Footnote 8) in France at the Belgian border near Tourcoing/Roubaix, or das rote Mössingen in Germany south of Stuttgart,Footnote 9 just as they advertised metropolitan strongholds: der rote Wedding (Berlin),Footnote 10 “Red Clydeside” (Glasgow),Footnote 11 “Red Poplar” (London),Footnote 12 or la banlieue rouge (Paris).Footnote 13 According to Michel Hastings the adjective “red”, eagerly attached to the names of communist strongholds, aroused a feeling of pride among people otherwise sustaining the burden of social anonymity.Footnote 14

Small-place communism, both industrial and agrarian, could be found all over Europe ever since the interwar period, based on a communisme identitaire, as Hastings aptly typifies Halluin's communism. In a social history of British communism, based on extensive prosopographical research, Morgan, Cohen, and Flinn argue that local communist attachments resulted from a “multiplier effect whereby the establishment of an effective party presence would itself then attract new recruits from environments hitherto untouched by communism”. This “snowball effect […] might help explain the extremely localized pattern of communist implantation”.Footnote 15 Later they reiterate their claim that “it is […] quality of leadership, in the sense of personal example, capability and articulacy, that best explains the more localized variables of communist implantation in Britain”.Footnote 16

Of course, local politics always requires personal activism and agency, and electoral results do also depend on the availability of popular and respected candidates,Footnote 17 but this kind of reasoning is not really convincing. It cannot explain why some communities proved more receptive to an alignment with the communist leadership than others, and why some developed into such persistent local strongholds. In my view, the explanation must be sought in the specific features, in sociological terms the ecology, of these local counter-communities. In this article, based on research into a number of cases in western Europe, I want to try to identify common characteristics which might explain their receptiveness to communist policies and ideas. As possible factors I have singled out: their geographical situation, occupational structure, immigrant participation, religious attitudes, militant traditions, and communist sociability. My aim is to present a taxonomy for further research, based on an inventory of similarities as possible explanations.

A more substantiated ecological methodology for analysing local differences in political affiliation would perhaps correlate local election results with explanatory factors of the type mentioned above. Indeed, Laird Boswell has done this in his research on communist implantation in the French Limousin and Dordogne regions,Footnote 18 but for a variety of reasons this is not really feasible on a European scale. I have used a more intuitive approach, based on a comparison of a number of cases selected on the basis of the availability of local investigations published in the past thirty years or so. An overview is presented in Table 1; their geographical situation is indicated on the map (Figure 1).

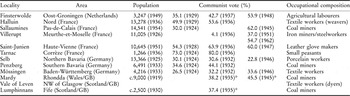

Table 1 “Little Moscows” in western Europe: population, communist vote, occupations.

*Parliamentary constituency of Rhondda East (Mardy) and West Fife (Lumphinnans) as a whole.

Figure 1 “Little Moscows” in Western Europe.

Admittedly, there are serious methodological shortcomings to selecting cases on the basis of the studies available. How, for example, does one define a small place? My cases range from agrarian villages of 2,000–3,000 inhabitants to industrial townships of about 10,000. Contexts could be quite different too, and have to be taken into account. Is it feasible for communist success in such different kinds of community to be explained by the same kind of explanatory factors? Is there really a specific kind of “small-place” communism which is unlike that found in large cities? How can one decide, as my sample does not contain large cities? It is also clear that this rather disparate collection of cases is not sufficient to allow one to decide whether the characteristics of the places concerned can be considered necessary or sufficient conditions for communist success. This can be resolved only by making comparisons with other small places which did not have a significant communist presence, or which were dominated by other political currents, such as social democracy. In several cases communist strongholds can be compared and contrasted with nearby localities, where socialists were in the majority. I am aware of these methodological problems, but my approach, based as it is on the existing literature about individual places, has the significant advantage that it enables me to gather information on cases in several countries. In this way, different national research traditions can be combined.

This criterion privileged France, not only because for a long time the Parti Communiste Français (PCF) proved to be one of the most successful communist parties in western Europe, but also because of the French tradition of research on the regional implantation of the PCF, which started in the 1970s with studies by communist historians from the Institut Maurice Thorez,Footnote 19 and which has since been expanded by historians around the journal Communisme, founded by the doyen of French communist history, Annie Kriegel.Footnote 20 I selected five cases in France. I have already referred to the glove-making town of Saint-Junien near Limoges, and to the textile town of Halluin (la Mecque, la ville sainte du communisme Footnote 21) in the far north at the Belgian border. Sallaumines, in the coal-mining basin of Pas-de-Calais, is also a case in point, as are the peasant community of Tarnac, representing the communist villages in northern Corrèze, and Villerupt, one of the Lorraine iron-mining communities in Meurthe-et-Moselle at the Luxembourg border near Longwy. The last area is particularly interesting as the PCF succeeded in taking those communities only after World War II, while it took the others during the interwar years.Footnote 22

For Britain I chose the well-researched case of Mardy in Rhondda (south Wales), and refer where possible to other “Little Moscows” mentioned by MacIntyre, namely the mining village of Lumphinnans in Fife (in Scotland, north-east of Edinburgh) and the textile communities in the Vale of Leven (also in Scotland, near Glasgow).Footnote 23

In Germany, the work of Klaus Tenfelde is important. In his study of the mining township of Penzberg, near the Austrian border in Upper Bavaria, he introduced the concept of punktuelle Industrialisierung (“isolated industrialization”).Footnote 24 Later he expanded and generalized his argument: “wherever industrialization happened [in] one single industrial community, similar signs of militancy and tensions within the environment could occur”.Footnote 25 The argument has been applied to other German cases of small-place communist implantation, especially in research connected with the post-1933 resistance to the Nazi dictatorship.Footnote 26 In addition to Penzberg, I have selected the porcelain manufacturing town of Selb, also in Bavaria, near the Czech border, and the textile town of Mössingen in Baden-Württemberg.Footnote 27 While they were relative strongholds of the Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands (KPD), there was no communist majority at the polls in any of these places before 1933. Unlike in France, prospects of further gain were cut off by Hitler's rise to power.

In the Netherlands, the communist-dominated agrarian village of Finsterwolde mentioned earlier is also a clear example. I have refrained from research in other European countries, both northern (Scandinavia, Finland) and southern (Greece, Spain, Portugal, Italy), though that would also have been very interesting from a local perspective.Footnote 28

Local variations

Many of the places I have selected were situated in larger areas of communist implantation. For these regions one could argue, as Chris Williams did for the Welsh Rhondda Valley mining district, that local communism was only a radicalized manifestation of regional militancy,Footnote 29 or, put differently, that regional communism radiated from local strongholds.Footnote 30 In these cases the wider regional context has to be taken into account, but from a localized perspective this can result in a spatial illusion, as there were extreme local variations within those areas. In the Welsh communist stronghold of Rhondda East for instance, Mardy's “Little Moscow” contrasted sharply with the relative weakness of the party's presence just a mile or two away.Footnote 31 The electoral history of the Fife “Little Moscow” Lumphinnans presents a stark contrast to nearby Cowdenbeath and Lochgelly, only half an hour's walk away, where the communists never outpolled the Labour Party.Footnote 32

In the French Lorraine border region around Longwy/Villerupt, after World War II communism gained the upper hand in iron-mining communities only, and it remained very weak in older boroughs and the central towns of Audun-le-Romain and Landres.Footnote 33 Also, among Lorraine coal miners the communist following remained very weak.Footnote 34 In the Corrèze department in the Limousin region, where the PCF generally scored highly, there were several places where the right had done consistently well throughout the last century, as in the canton also called Corrèze, bordered on three sides by the cantons of Seilhac, Treignac, and Bugeat, which were among the reddest in the department and in France as a whole.Footnote 35 The social structure in these cantons was similar, however. The differences at the village level could also be substantial.Footnote 36 There were also more gradual differences: of the Corrèze communist communities, the village of Tarnac in the canton of Bugeat particularly stood out: in 1924, 73 per cent of its votes went to the communist list; in 1936, the PCF received as much as 80 per cent.Footnote 37 Its success in Tarnac has to be seen in the context of the results for the communists in the canton of Bugeat as a whole, however.Footnote 38 In the west of Limousin, the socialist majority returned by voters in its capital Limoges contrasted with the stubborn communism of nearby Saint-Junien.

In the French region of Nord-Pas-de-Calais the PCF became well-established in the coal-mining districts, more particularly in those east of Lens, but its local implantation there was also very irregular.Footnote 39 Sallaumines (near Lens) stood out already in the 1924 election. There the PCF took 30 per cent of the vote. In other mining communities in this area, however, its results were quite modest, around 2–3 per cent. Sallaumines proved to be very loyal during the 1920s and 1930s, and in 1935 the PCF gained a majority there, but in adjacent Noyelles-sous-Lens the socialists held on to their lead.Footnote 40

Outside the mining area, from the early 1920s the PCF gained a majority in its most northern communist bastion, Halluin in the textile region of Lille-Roubaix, but the town was politically isolated. Its twin town on the Belgian side of the border, Menin, remained a stronghold of Belgian socialism, although many of its inhabitants worked as frontier workers in Halluin's textile mills.Footnote 41 On the French side of the border, the neighbouring communities in the Vallée de la Lys were very hostile towards communist Halluin.Footnote 42 Politically it remained a citadelle assiégée.Footnote 43 In this respect Halluin resembled the German border towns of Penzberg and Selb. Hostility towards das Kommunistennest Penzberg even resulted in the murder of several socialists and communists by radicalized Nazis on the eve of liberation (29 April 1945).Footnote 44 Before 1933, the KPD's electoral results in Penzberg fluctuated from a low point of 10.8 per cent in 1928 to a high point of 44.1 per cent in the Reichstagswahl of July 1932, while in the nearby mining town of Peißenberg the Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD) held the upper hand, with results for the KPD fluctuating between 2.8 per cent in 1928 and 19.1 per cent in November 1932.Footnote 45 Communist electoral results in Selb reached a steady, and in the wider border region and in Bavaria as a whole exceptional, 30 per cent during the 1920s and early 1930s.Footnote 46

Last but not least, the communist villages of Finsterwolde (42.7 per cent for the Communistische Partij Nederland (CPN) in 1937), its twin village of Beerta (23.9 per cent), and Nieuweschans (23.1 per cent), situated on the German border in the far east of the Netherlands's most northern province of Groningen, were alone among the other, more inland villages with socialist majorities, or – more surprisingly – villages with strong orthodox Calvinist leanings, such as nearby Midwolda.Footnote 47

In sum, “locality” was a major factor in communist implantation, both in isolation and within a militant regional environment. In the following sections I will try to identify the characteristics common to these places which might explain their exceptional political orientation.

Crossing borders in the periphery

Can we attach any significance to the fact that no fewer than five of my cases (Halluin, Villerupt, Selb, Penzberg, and Finsterwolde) are situated on a national border? It is at least remarkable. The same phenomenon can be found in Sweden too, where places which recorded the highest communist vote (above 35 per cent in the period 1924–1952) are situated either in the far west on the Norwegian border (Nyskoga, Vitsand), or in the far north on the Finnish border (Tärendö, Kiruna). These were isolated, irreligious frontier communities of forest workers.Footnote 48 According to anthropological border studies, borderland inhabitants often exhibit a subversive attitude towards the national state. Both the weakness of the state at the border and the opportunities for border crossing provide occasions for semi-legal acts and behaviour, both economically and socially.Footnote 49 Moreover, border crossing can lead to a transformation of values and to specific deviant border identities, both relational and confrontational vis-à-vis those on the other side.Footnote 50 Though not a necessary condition or consequence, this subversive attitude and transformation of values could have made the inhabitants receptive to oppositional ideas, such as those of communism.

Perhaps people who had come to work in border towns from the other side of the border had crossed it in a metaphorical and symbolic sense too. The KPD leadership in the porcelain town of Selb included many migrants who had arrived from nearby Saxony, Thuringia, and Czechia before World War I.Footnote 51 It was quite common for porcelain workers from the Czech border town of Asch (Aš), just a few kilometres from Selb, to commute. Asch also had a sizeable communist electorate (39.9 per cent in 1932).Footnote 52 There were more isolated centres near the Czech border with a strong communist electoral base, including the glass manufacturing village of Frauenau (population 3,026 in 1933), known as das rotes Glasdorf or Bayerns rote Insel.Footnote 53 The first generation of miners in the border town of Penzberg had arrived at the end of the nineteenth century from a mixture of nations belonging to the neighbouring Austro-Hungarian Empire: Slovakia, Croatia, Bohemia, and South Tyrol.Footnote 54

In some cases, cross-border relations were clearly of great importance for socialist and later communist implantation. The most obvious example is Halluin where, from the end of the nineteenth century, socialism was introduced among Flemish migrants (and their descendants) and cross-border commuters by propagandists from the Flemish socialist hometown of Ghent (just 60 kilometres away). It is tempting to suppose that their trans-frontaliérité (Hastings) made them receptive to socialist internationalism.Footnote 55 It is no coincidence that Menin, Halluin's Belgian twin border town, became an early socialist stronghold in the same period. Contemporary observers noted that Flemish frontier workers could literally distance themselves from the influence of the church and other authorities, had an independent mind, and were therefore accessible to socialist ideas.Footnote 56

That Menin did not follow the communist reversal of Halluin's socialists after 1920 is another, though from a border perspective very significant, matter. It foreshadowed a more general phenomenon of the nationalization of electoral behaviour and communist success, also at a local level, in the years to come, especially after World War II, as Serge Bonnet argued in a comparative study of the communist vote in Lorraine and its borderlands. While in all the border districts on the Belgian side, from the North Sea to Luxembourg, the average size of the communist vote reached 8 per cent in 1950 and 6.4 per cent in 1954, on the French side it was 26.5 per cent in 1951 and 27.1 per cent in 1956.Footnote 57 Becoming a communist increasingly meant becoming a French communist.Footnote 58

On the Lorraine border, the post-World-War-I revolutionary movement in the mining district in the south of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg (in 1921 the ARBED steel works, just a kilometre across the border near Villerupt, were occupied) influenced the Lorraine workers too, facilitated perhaps by the cross-border mobility of Italian migrants, a number of whom had participated in l'occupazione delle fabbriche in Italy in 1920.Footnote 59 In Villerupt “the three words worker, Italian, and frontier constituted a dangerous combination”.Footnote 60 The electoral breakthrough by Lorraine's communists came only after World War II, however. The Luxembourg CP disappeared in the mid-1920s, but was refounded in 1928, after which it gained some success in the industrial south.Footnote 61 After World War II, communist electoral support in the Luxembourg border town of Esch-sur-Alzette grew from 15.1 per cent in 1954, to 15.3 per cent in 1959, 17 per cent in 1964, and to 22 per cent in 1968, paralleling increasing communist support in the Lorraine communities on the other side of the border in the Longwy region. Both can be explained by the presence of voters of Italian descent,Footnote 62 putting the nationalization of communist voting mentioned above in another perspective.

Pioneer societies, second-generation migrants, and “negative integration”

In Great Britain

Within the British coalfields, communist communities might not have been more isolated than others, but this was certainly the case with Welsh “Little Moscow”, Mardy.Footnote 63 Before the 1920s, Mardy had been a new and booming part of the Rhondda coal rush, attracting both Welsh and English immigrants since the opening of its collieries in the 1870s. It was distinctive, not only because of its geographical isolation, but also because of the comparative lateness and swiftness of its growth.Footnote 64 Its workforce was mobile and variegated, and had only recently settled there.Footnote 65 Between the 1870s and 1909, Mardy had grown from just a farmhouse to a settlement of 880 dwellings, housing 7,000 inhabitants, reaching nearly 9,000 by the end of World War I.Footnote 66 The South Wales Daily News, reporting on Mardy as “Little Moscow” in 1926, wrote about “the young Communists of Mardy”,Footnote 67 and these must often have been second-generation immigrants, born in Mardy itself, such as the notorious Arthur Horner (1894–1968), of English, not Welsh, descent, later (1946–1959) to become the leader of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM).Footnote 68

Being a new settlement, only recently populated by migrants, seems to be a common characteristic of many of the communities in my sample. “Little Moscow” Lumphinnans in Fife, Scotland, was built in the 1850s and 1860s as a company settlement by a coal-mining company; its population increased from 404 in 1871 to 1,007 in 1891 and doubled again over the next decade.Footnote 69 And although the society in the Vale of Leven was older, larger, and more complex than the mining villages of Mardy and Lumphinnans, its employers had established new extensive tenement accommodation for their workers in two of the main settlements, similar to the mining villages mentioned above.Footnote 70

In Germany

The cross-border migration to the German border towns, mentioned above, can be related to a fairly recent economic upsurge in the last quarter of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century. According to Georg Goes, who compared the political attitudes of four glass and porcelain towns in south-east Germany, communist preponderance was related to late industrial development: “Late industrialization and recently established factories […] are characteristics of industrial communities that predominantly voted communist.”Footnote 71 Hartmut Mehringer, in his study on the KPD in Bavaria, has also related the implantation of the KPD in specific areas to late industrialization in isolated industrial communities.Footnote 72

There were only a few farmsteads in Penzberg in the mid-nineteenth century; workers’ housing was erected here by the mining company from the 1870s, and, together with the mining labour force, Penzberg's population grew from 1,620 in 1880 to 4,000 in 1910 as the town attracted migrants from a range of neighbouring countries. After the turn of the century, the town grew primarily by natural increase. This affected the age structure significantly: this was a relatively young community.Footnote 73 As a consequence, most miners recruited in the 1920s were born in Penzberg itself,Footnote 74 a characteristic reflected in the complexion of the KPD leadership of the 1930s, most of whom were born there in around 1900.Footnote 75 In 1932 all party members were younger than forty.Footnote 76 Tenfelde writes about the radicalization of this generation, particularly after World War I.Footnote 77 Judged by the demographic history of the town, these must have been second-generation migrants. In nearby Peißenberg, where the KPD remained much weaker, almost all miners originated from miners’ families in the town itself.Footnote 78

The porcelain industry in Selb had been established in the 1850s, but it developed at only a moderate pace until the 1890s, when a sudden expansion started. Like Penzberg, Selb at first experienced a high rate of immigration, but even before World War I the birth rate began to determine its population growth. So, again as in Penzberg, its population was relatively young.Footnote 79 Mössingen seems to represent an exception in this respect. Its textile factories, established since the 1870s, were able to recruit workers from proto-industrial families in the village itself: until World War I 90 per cent of its population was ortsgebürtig.Footnote 80

In France

Saint-Junien

This pattern can be recognized too in the small French industrial towns and villages with communist majorities. Petit Moscou Glane, part of Saint-Junien, had undergone a transformation from an agrarian village to an industrial neighbourhood in the 1860 and 1870s, and it saw its population increase rapidly at the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century, partly owing to immigration from the surrounding countryside, which peaked in 1921.Footnote 81 Saint-Junien as a whole grew in the same period, especially at the end of the nineteenth century, from 8,153 inhabitants in 1876 to a maximum of 11,432 in 1901, owing to the migration of poor peasants from the countryside in search of employment, predominantly in the glove-making industry.Footnote 82

The Longwy region

In the mid-nineteenth century, the Longwy region in the north-east of France was a small, sparsely populated rural canton, composed of dozens of villages centred on the principal town of Longwy, with a population of just over 2,000.Footnote 83 In 1861, Villerupt had 561 inhabitants.Footnote 84 The area was rather isolated from the rest of France,Footnote 85 and this was accentuated after the German annexation of part of Lorraine in 1870, when the Franco-German border was drawn just east of Villerupt and the Longwy basin became something of a French peninsula.Footnote 86 The region's initial industrial development dates from this period but, shortly after 1900, a real industrial euphoria started, when new layers of high-quality iron ore were discovered. Mining suddenly expanded, as did steel manufacturing. Labourers were recruited from the surrounding countryside, from across the Belgian border, and from Italy, the last ones almost exclusively to work in the iron mines. The mines which sprang up in the area after the start of intensive exploitation in 1902 became an Italian universe.Footnote 87

Growth continued until 1930, with migrants coming from many countries, but mostly Italy. In 1928, Villerupt had 21 nationalities in a population of around 10,000.Footnote 88 Some 50 years before, in 1881, it had only 1,226 inhabitants, exploding to 8,569 in 1911.Footnote 89 The region as a whole has been characterized as a series of worker colonies (cités) around industrial plants, monotonous agglomerations hardly ever exceeding 10,000 habitants. Migrants were concentrated in these cités, while the French continued to live in the old villages.Footnote 90 It is in those banlieues sans villes, or parcs à main-d'oeuvre, as Serge Bonnet called them, that communism found its strength, not in the village or in urban centres such as Longwy itself.Footnote 91

After the end of immigration in the 1930s a stable workforce emerged, composed of second-generation Italians, who entered the mines and the steel works in this period. They were the basis of postwar communist success. Representatives of this second generation took the lead in implanting the PCF during the 1930s and, especially, during wartime Résistance.Footnote 92 According to Noiriel, the Italian communists continued their struggle against Mussolini in fighting pour la France. For second-generation Italians, adhering to the PCF and participating in the resistance were a means to accomplish their integration into France and to acquire a national identity.Footnote 93 The result was, as Bonnet wrote in 1962, that “In many respects, the Italian communist militant is the most integrated, the best adapted, and even the most assimilated in local society. It is no exaggeration to call him a prototype of assimilation and identification”.Footnote 94 In the late 1950s and early 1960s the communists won control of the mairies of municipalities with a large Italian presence: Villerupt in 1959, and somewhat later also Longlaville, Saulnes, and Mont Saint-Martin near Longwy.Footnote 95 In this way, as Serge Bonnet argued, “The PCF and the trade unions in Lorraine assure the formation, the promotion, and the integration of working-class dignitaries, predominantly from the immigrant population. […]. These counter societies at a micro level play an integrative role in the wider society which they pretend to destroy.”Footnote 96

Second-generation communist recruitment connected to national integration has also been observed in Britain by Morgan, Cohen, and Flinn in the case of Jewish migrants in the 1930s.Footnote 97 The phenomenon has been described in the case of the German SPD before World War I as “negative integration”, and this seems to be an adequate term in this context too: “From the viewpoint of the historical participants this phenomenon may primarily appear as a matter of purposive isolation or self-containment, but from the viewpoint of the observer it can be recognized as a form of integration.”Footnote 98

Sallaumines and Noyelles-sous-Lens

In the coal-mining communities in Pas-de-Calais, the continuous growth in production and employment in the mines between the 1860s and World War I had resulted in a steep increase in the size of the population in both Sallaumines (a communist stronghold since the 1920s) and Noyelles-sous-Lens (much less so), partly owing to migration from the surrounding countryside in Pas-de-Calais, and from more distant regions in Kabylie (Algeria) and above all Belgium.Footnote 99 In the 1850s these had been small villages of 628 and 190 inhabitants respectively.Footnote 100 There were important differences between them however: between 1851 and 1911 Sallaumines grew by 77.4 per cent, Noyelles by “only” 32.9 per cent.Footnote 101 In spite of their many resemblances, Sallaumines and Noyelles-sous-Lens differed in the speed of industrial development, population growth, and spatial restructuring.

Figure 2 Poster to celebrate forty years of communist majority in Finsterwolde (The Netherlands), 1975. Collection IISH.

Figure 3 Mardy miners and their families photographed at the arrival of a banner made by “the working women of Krasnaya Presna, Moscow”, December 1926. Crowded into the photograph were all the local communists, male and female, and their children. Note the life-size portrait of Lenin in the background. The banner was kept at the Mardy Workmen's Hall, to be used only on such special occasions as communist funerals when it draped the coffins. The picture is a fine illustration of the integration of local communism into family life. Reproduced in Francis and Smith, The FED, p. 53.

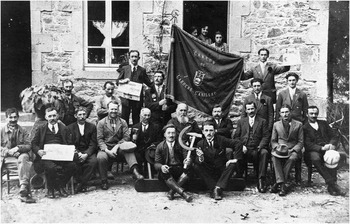

Figure 4 A meeting of communist-cell delegates in the canton of La Roche-Canillac, Corrèze, October 1928. Note the female onlookers in the windowpane, reflecting the subordinate position of females in the party's political life. Fédération du Parti Communiste Français de la Corrèze. Used with permission.

While in most mining villages, and also in Noyelles, there was a distinction between the village and the miners’ colonies, between the centre around the church, the mairie, the school, and the shops on the one hand, and the peripheral mining colonies on the other, this was not the case in Sallaumines.Footnote 102 In Sallaumines new housing accommodation for miners’ families was erected in a forced rhythm, to keep up with demographic growth. Few remnants of the old village remained, the more so after its destruction during World War I. Noyelles developed more gradually, without these effects on its spatial structure. The new miners’ quarters were at a distance from the old village, which kept its integrity, organized around the church as a symbol of traditional society.Footnote 103 This affected social life (la sociabilité) too. People from the village centre in Noyelles, being richer than those of the miners’ quarters, and therefore able to subsidize social activities, took the lead in local societies, but there was no sociabilité communal unificatrice. In Sallaumines, with a homogenous population centré sur les fosses, all social activities depended on municipal subventions.Footnote 104

Postwar reconstruction in the 1920s attracted new waves of migrants to the French coalfields, this time of Polish origin, both experienced miners arriving from the Ruhr (so-called Westphaliens) and from Poland itself. Both in Sallaumines and Noyelles two-thirds of the population growth seen in the 1920s was a result of Polish migration; in the 1920s almost half of the population were Poles. Until the 1930s net migration accounted for 62.4 and 67.9 per cent of growth in both villages, but, as in Lorraine, in the depression of the 1930s migration came to halt; many Poles were even sent home. While in the 1920s the first generation of Polish migrants lived and organized separately in véritable ghettos in both communities, in the 1930s the Poles began to adapt to the different political milieus of each town. Social and political integration was achieved only by a second generation of Poles after World War II, however, when this generation, born in France, started their working life. In Sallaumines they were rapidly assimilated into the local community, with mixed marriages, trade-union militancy, estrangement from the Polish priest, and political support for the PCF. In Noyelles, things developed differently: until the 1950s Polish inhabitants remained segregated in their isolated cités and organized their own social life.Footnote 105

Arguably, the structural social differences between both mining villages can be considered part of the explanation for the difference in voting behaviour. In general, different political attitudes in mining communities in interwar Pas-de-Calais have been attributed to a restructuring and renewal of the mining labour force before World War I in what later became communist localities.Footnote 106 In Germany, a comparable political radicalization in the 1920s has been observed for newly erected mining colonies on the northern fringe of the Ruhrgebiet, contrasting with the political orientation in the old village centres.Footnote 107 The KPD was able to establish itself as a political force in the industrial quarters of this northern fringe, which were hastily built in the period of forced industrialization after the beginning of the twentieth century and populated mainly by Polish migrants from what was then the Prussian east.Footnote 108 A detailed study of election results in one of these colonies, Bottrop, reveals that in the 1920s the KPD succeeded in making headway into the world of Catholic Polish miners there.Footnote 109 Polish miners from Upper Silesia had been settling in Bottrop since the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Therefore, “the Ruhrpolen living there were partly second generation, while it was precisely the people from Upper Silesia in Bottrop who had stayed there for longest and had been forced to put down deep roots in their new Heimat”. While in the 1920s other Polish migrants left for their now independent fatherland, or the coal mines in Pas-de-Calais, these “rooted”, second-generation Upper Silesians remained in Bottrop, and formed the backbone of the KPD electorate in that period.Footnote 110

Halluin

While the PCF gained a majority in Villerupt in 1959, and in Sallaumines in 1935, in its other northern stronghold of Halluin this had already been achieved in 1920. The socialist majority on its municipal council, elected in 1919, adhered in its entirety to the Third International in 1920, and managed to hold on to its majority as PCF representatives in the following elections.Footnote 111 Interestingly, the whole sequence of fast but isolated industrial development, population growth predominantly owing to immigration, then stabilization, and political radicalization of the second generation can be found in Halluin too, but in an earlier period.

Its urban growth in the nineteenth century was “disorderly”, according to Michel Hasting, especially between 1850 and 1870, when Halluin was “destabilized” by the influx of Flemish migrants.Footnote 112 As a booming textile town, it became one of the destinations for the waves of migrants from “poor Flanders” in the 1850s and 1860s. In the fifteen years between 1851 and 1866 Halluin's population increased by an average of 10 per cent annually, from 5,408 to 13,673. At that time, it was the fastest-growing town in the northern textile region as a whole. After 1866, growth slowed down, with Halluin's population peaking at 16,599 in 1901. Thereafter, population stabilized, and later even diminished by several thousand.Footnote 113 The proportion of “strangers” born outside France (almost all of them Belgians) rose to about 75 per cent in the late 1880s/early 1990s (much higher than in other northern textile towns), but after that it quickly fell until it reached about 25 per cent after World War I. A process of indigenization is clearly visible: most of Halluin's interwar population were born to second- or third-generation inhabitants of Belgian descent.

Unsurprisingly, the labour movement in Halluin had a distinctly Flemish “flavour” from its beginnings at the turn of the century, as can easily be deduced from the names of the early socialist and trade union leaders: Vanlaecke, Muleman, Vansieleghem, Verkindere, Goerland, Vandewattyne, Vanoverberghe, Vansteenkiste, Vandeputte, and Desmettre. Many of them were to become communists in 1920.Footnote 114 On the basis of a sample of twenty-eight militants known in 1912, Hastings concludes that at that time they were relatively young (in their thirties). Three-quarters had been born in Halluin from parents born elsewhere, the others had arrived from small Belgian villages in the neighbourhood. So again, these were predominantly second-generation migrants.Footnote 115 As in the case of an Italian electorate integrating in Lorraine and voting communist after World War II, there is a clear correspondence between the presence of increasing numbers of settled and naturalized Flemish migrants and the rise of socialism in Halluin before World War I. Like Serge Bonnet and Gérard Noiriel, Hastings regards the socialist vote of the children of migrants as an act of assimilation.Footnote 116

A sample of ninety-six communist militants in 1925 confirmed their flamandité: 84.2 per cent had been born in the town itself, but 82 per cent had Belgian parents, and can be considered second or third generation. This corresponded with the composition of elected working-class members in the municipality: 90 per cent were born in Halluin; 88 per cent were of Flemish descent, a clear sign of their successful integration and the integrative role of the PCF.Footnote 117 Like Michel Hastings, we may conclude that “Halluin la Rouge was the adventure of a communisme générationnel, like that of Longwy studied by Gérard Noiriel”.Footnote 118

Isolated occupational communities, trade unions, and communist sociability

Occupational coherence

Halluin's communists did not represent local society as a whole, but only its working population. There is a clear connection with the typical composition of Halluin's industrial working class: in the sample of 28 militants in 1912, 65 per cent were employed as weavers in one of the town's textile mills. In 1925 this figure was even higher, at 81.8 per cent, higher than in the population as a whole, a clear sign of the occupational coherence of communist militancy.Footnote 119 One of the more salient features of these “Little Moscows” is, indeed, that they were all dominated by specific industries, and in many cases this was reflected in the social profile of party members and militants. However, this was not necessarily so. In the other textile towns in my sample – the Vale of Leven in Scotland and Mössingen in Württemberg – leading communists were not drawn primarily from among the factory workers.Footnote 120

Communist membership in other cases did to a large extent reflect local occupational specialization. In 1920, almost all KPD members in Selb were working in the local porcelain industry (as either skilled or unskilled workers).Footnote 121 In 1931 all leading communist figures in Selb were porcelain workers.Footnote 122 In Frauenau, the KPD was the party of the glass workers; at least one-half of its candidates worked in one of the glass factories.Footnote 123 In the Corrèze villages smallholding peasants formed the great majority of those who ran for office for the PCF. That peasants dominated municipal councils can be considered a reflection of the social composition of the communist electorate in these villages.Footnote 124 The peasants often also managed to mobilize support from village artisans and shopkeepers, however.Footnote 125 In Saint-Junien the PCF was based in the leather and glove-making industry there,Footnote 126 but the peasants in the town's orbit also contributed to the party's success.Footnote 127 In the agricultural village of Finsterwolde, communism derived its strength from proletarian farm workers, opposed to the wealthy farmers in the village.

For the mining towns the occupational base was even more self-evident. In Penzberg in 1931 at least two-thirds of KPD members were miners, and probably 80 per cent were related to the mine or belonged to miners’ families.Footnote 128 In Sallaumines, in the period 1919–1935, 58.7 per cent of the members of the municipal council were miners, compared with 28.4 per cent in Noyelles-sous-Lens.Footnote 129 As trade-union militants, association officials, or municipal councillors, the Sallaumines miners had clearly succeeded in becoming representatives of the population as a whole.Footnote 130

Trade unions

The occupational base of communism was mediated by local trade unions. In Saint-Junien, in the 1920s the labour movement was based on the radical Confédération générale du travail unitaire (CGTU), a trade union dominated by workers in the glove industry.Footnote 131 In Halluin, “Unionism [was] the driving force of communist implantation […], its Trojan Horse, its waiting room”.Footnote 132 Trade-union strength in Halluin can be related to the industrial homogeneity of its working population, as was the case in the mining communities in my sample. In Sallaumines, working and living being more closely connected than in Noyelles, and the miners’ union had much greater influence on daily life and village identity.Footnote 133 In Lorraine in the early 1960s, Bonnet noted a close correlation between the advance of the Confédération générale du travail (CGT) in the iron mines and communist voting in the mining villages.Footnote 134

Alberto Balducci, a regional trade-union leader in the Meurthe-et-Moselle iron mines, regarded himself as “a CGT member first and a communist second”.Footnote 135 His attitude was in fact not so different from that of the British mining leader Arthur Horner from Mardy in Wales.Footnote 136 Organized communist influence in Mardy in the 1920s was based on control of the local trade-union committee (“lodge”).Footnote 137 The position Arthur Horner was able to attain in the South Wales Miners’ Federation (he became president in 1936) found its counterpart in that assumed by the Lumphinnans miners’ communist leader Abe Moffat, who became president of the Scottish miners in 1942. As in Mardy, local communist influence in Lumphinnans was rooted in trade-union militancy at the workplace, in a situation of close identity between work and residence.Footnote 138 In communist strongholds in the British mining districts the union, and not the party, was often regarded as the main vehicle of political activism. According to communist trade-union leader Will Paynter, the typical South Wales coalfield activist was a miner and trade unionist first, and a communist only second. His activism was rooted in “the communities around the pit, the union branches were based upon it, hence the integration of pit, people and union into a unified social organism”.Footnote 139

Trade-union adherence has also been put forward as an important factor in the success of agrarian communism in the French Corrèze department.Footnote 140 The existence of an agricultural trade union, the Syndicat des Paysans Travailleurs, closely linked to the party, was an original characteristic of Corrèze's communism. In no other French department did this union establish such firm roots during the interwar years, not even in other red departments of Limousin, such as Creuse and Haute-Vienne.Footnote 141 It was no coincidence that one of the party's main national peasant organizers in the 1920s, Marius Vazeilles, came from this area. According to Boswell, there were strong links between membership of the Syndicat and communist votes: the local presence of the union was an excellent predictor of solid party support at the polls,Footnote 142 for instance in Tarnac, one of the first villages in 1920 to create a union branch.Footnote 143

Occupational communities and communist sociability

Trade unions enabled communists to connect workplace experiences to local politics, and to transform these isolated, mono-industrial or agricultural localities into “occupational communities”. A “locality” is just a place where people live together; it can become a “community” when local networks of social relationships are established, with high levels of interaction among insiders and isolation from outsiders. In the social history of mining, the idea that miners in small settlements were a so-called isolated mass, forming an “occupational community”, is a familiar topic, more specifically in the context of the propensity of miners to strike.Footnote 144 It has been broadened to other characteristics of mining settlements as well.Footnote 145

Sociological theories suggesting that differences in the degree of social isolation and occupational homogeneity of working-class groups are major factors influencing variations in militancy have the advantage that they can explain how experiences in the workplace were connected to social relationships in mono-occupational localities or neighbourhoods. However, to avoid the “ecological fallacy” inherent in this reasoning, implying that we explain social behaviour by structure without agency,Footnote 146 these factors can, in my view, be related to small-place communism only if we consider the agency of both trade unions and other forms of communist sociability.

Both were important in the process of socializing with “our own kind”, the social and cultural clubs and societies, because they also involved family members of predominantly male occupational groups. Only in the rich associational life of these communities do we encounter women and girls, as communist political and trade-union activities were an exclusively male domain. In mining communities this comes to no surprise, as “the miner” combined the archetypical status of both “communist proletarian” and “masculinity”,Footnote 147 but the gender balance was very uneven everywhere, even where female labour was more common, as in the textile towns.

Efforts to organize a separate social sphere in and for the local working-class community were a defining feature of communist political culture. Social and cultural events embedded the party in everyday life, sustained local networks of sociability, and strengthened a sense of local identity. In Mardy, and in Rhondda East in general in the interwar years, the communists had “an inclusive culture”; one could “live and die in a world whose boundaries were defined by the Communist Party”.Footnote 148 The German labour movement in general, both the SPD and the KPD, had a very rich associational and festive culture.Footnote 149 In small Corrèze villages the Jeunesses Communistes regularly held bals rouges or bals populaires, others organized Noëls rouges.Footnote 150 By creating new networks of sociability, Boswell argues, the communists filled a gap, because in the Corrèze villages in which the communists had a significant presence church-related sociability was often non-existent.Footnote 151 A communist festive culture is to be found in other French places as well, adapted to local customs. In Halluin, festivities, celebrations, and processions were embedded in Flemish folklore;Footnote 152 in the Longwy region it was associated with an Italian festive style of music and dance designed to stir the enthusiasm of second-generation workers.Footnote 153 In mining towns in Pas-de-Calais, local bals populaire or other festivities had clear political functions too, namely to promote the trade union or other working-class organizations.Footnote 154

In French municipalities administered by communists, associational life was to a great extent promoted and fostered by the municipalities themselves. In Halluin, communists were very active in associated societies, clubs, and circles, facilitated by the municipally sponsored Maison du Peuple.Footnote 155 Also in Sallaumines, patronage by the church or the mining company of associations such as brass bands or sports clubs could be avoided by municipal sponsoring.Footnote 156 In the Longwy region, communist municipalities encouraged social participation by supporting associational activities; in Villerupt alone, there were fifty-six municipally sponsored associations in 1964, covering a range of activities including sport, youth, culture, and social support.Footnote 157

Religious indifference, militant traditions

Considering the causes of small-place communist success in the interwar years and after, we cannot ignore its history prior to World War I. Two factors stand out: traditions of religious indifference and of pre-communist militancy, which were sometimes closely related. There are in fact two types of local political prehistory: one of anarchism or revolutionary syndicalism, particularly in Finsterwolde, Sallaumines, Saint-Junien, Mardy, and Lumphinnans; and another of Second International socialism, as in the German cases (Germany generally lacking a syndicalist pastFootnote 158) and Halluin (as an offspring of Flemish socialism), and of rural communism in the Corrèze. Socialism had established a geographical base of support there before the communists inherited and strengthened it in the 1920s.Footnote 159

The religious history of the Corrèze department is particularly relevant for an understanding of local variations in socialist and later communist implantation. According to Boswell, detachment from Catholicism and religious indifference was the best predictor of local communist success. Low rates of religious practice, hostility to religion, and the absence of the church at a local level all proved favourable to communism.Footnote 160 The remarkable differences in voting behaviour between the northern and southern parts of the Corrèze department, and also, as mentioned before, between the canton of Corrèze (where the communist electorate remained relatively small) and the surrounding cantons of Seilhac, Treignac, and Bugeat (dominated by the PCF), can be explained by, or at least correlates with, differences in religious behaviour.Footnote 161 These differences were not caused by the party's presence, but predated communist implantation.

The Corrèze department was already divided into a religious southern and indifferent northern part on the mountain plains, later to become communist strongholds, from around 1900. The cleavage was produced between 1900 and 1910. Compared with the adjacent Creuse and Haute-Vienne departments this was relatively late, however.Footnote 162 Remarkably, socialist implantation predating the communist reversal was also later in the northern Corrèze than in Creuse and Haute-Vienne: it emerged quite suddenly after World War I, when the socialist Section Française de l'Internationale Ouvrière (SFIO) obtained more than 50 per cent of the vote in the canton of Bugeat (in 1919) for instance. Before the war, this had been less than 10 per cent, much lower than in Creuse and Haute-Vienne.Footnote 163

How can one explain these divisions and time lags? In the late nineteenth century, socialism in the Haute-Vienne had spread from its urban stronghold of Limoges to the surrounding countryside, but it had not yet reached the isolated Corrèze villages. There, socialism and religious indifference had been influenced by a direct link with Paris. Although Boswell refutes any statistical correlation between places of origin of migratory labour – traditional in Limousin – and communist implantation, it can nevertheless be argued that at this sub-regional level it was in fact very relevant.Footnote 164 Migrant labour from the southern cantons of the Corrèze was less frequent, had different (often rural) destinations, and related to specializations other than those of the north. In the canton of Bugeat, which became the reddest in the Limousin and perhaps anywhere in France, with the PCF winning 53.9 per cent of the vote in 1928 and 61.4 per cent in 1936,Footnote 165 party veterans and parish priests were united in their opinion that temporary migrants had influenced both irreligiousness and political radicalization.Footnote 166 Since about 1880, Bugeat migrant workers had acquired a new specialization as coachmen (cochers de fiacre) in Paris,Footnote 167 while before they had been primarily sawyers (scieurs de long) in rural areas, and, according to Pérouas, this could have influenced their religious attitude.Footnote 168 At least the priests of this canton considered it the main reason for the decline of religious practice.Footnote 169

A correlation between localized non-religious or anti-religious attitudes since the nineteenth century and communist implantation after World War I can also be found in the east Groningen villages of Finsterwolde and Beerta. Since the 1840s prosperous and ultra-liberal farmers had dominated the Dutch Reformed Church in these pioneering non-nucleated polder villages (the last polder in this area had been reclaimed in 1819). They appointed modernist preachers and estranged the workers from the church in this way, in contrast to the neighbouring villages.Footnote 170 In the 1890s the irreligiousness of the Finsterwolde working population was strengthened further when anarchism gained a foothold there. In fact, as in several other places which we will discuss below, anarchism was the direct precursor of communism in the 1920s.Footnote 171 As early as 1918, a previous left-wing splinter faction within the Dutch social democratic party had called itself “communist” (CPN) and could profit from anarchist enthusiasm for the Russian Revolution. Within a few years the CPN succeeded in attracting the former anarchist following, who began to participate in elections as communists and gained municipal seats there. Communism's electoral breakthrough in Finsterwolde came only after a prolonged strike by agricultural workers in 1929.

The northern French mining district around Lens was an early area of religious indifference as well. From the 1860s and 1870s its eastern part had the lowest level of religious practice (Easter communion) in the north, and perhaps in France as a whole. The opposition between the attitudes of the inhabitants of the traditional villages and those of the newly established miners’ corons, as mentioned earlier in the cases of Noyelles-sous-Lens and Sallaumines, was already evident at that time.Footnote 172 From the end of the nineteenth century, socialism and trade unionism were followed massively by une classe ouvrière déchristianisée, and at the beginning of the twentieth century anarchist groups sprang up there, especially in localities east of Lens.Footnote 173 In 1902 a militant anarcho-syndicalist miners’ union (which became known as le jeune syndicat) broke away from the moderate reformist trade union linked to the socialist SFIO (le vieux syndicat).

Anarchism had a decisive influence in le jeune syndicat, which found its strongest base in the mining communities east of Lens as well.Footnote 174 Named after their anarcho-syndicalist leader, Benoît Broutchoux, les broutchoutistes created local sections in this part of the Pas-de-Calais mining district, in Sallaumines and elsewhere, but not in Noyelles-sous-Lens.Footnote 175 In the 1920s, membership of the prewar syndicalist jeune syndicat was continued in the radical CGTU, despite the uneasy collaboration between communists and syndicalists. This was also reflected in local differences: of the miners born between 1901 and 1920 who had gone to work in the mines between 1915 and 1934, 44.4 per cent were members of the CGTU in Sallaumines, compared with 22 per cent in Noyelles.Footnote 176 In general, the implantation of the PCF in this area in the 1920s succeeded best in the few localities, such as Sallaumines, where anarcho-syndicalism had been strong, while socialists retained their lead in the former bastions of the vieux syndicat.Footnote 177

Some 600 kilometres to the south, Saint-Junien had been yet another centre of anarchism.Footnote 178 In the early 1900s, anarchist groups such as la jeunesse syndicaliste or Germinal, had united hundreds of members, mainly glove-makers. In the 1920s, the Saint-Junien socialists turned communist and managed to politicize and mobilize for the elections the formerly non-voting anarchist group, and also a new generation, resulting in a much higher turnout at the polls and a communist victory in 1925.Footnote 179 In the early 1920s anarcho-syndicalism still exercised considerable influence in the Saint-Junien CGTU, but after 1923 the communists took over.Footnote 180

Also, in far away Scottish Lumphinnans communism had been predated by anarchism. In 1908, an Italian immigrant called Storione (or Storian), an anarchist who had worked in mines in Italy, France, Belgium, and the west of Scotland, had formed an Anarchist-Communist League there, and influenced a number of younger Lumphinnans miners who later joined the Communist Party.Footnote 181 Lumphinnans was also the least religious of the British “Little Moscows” described by MacIntyre.Footnote 182 In the Rhondda coalfield Spanish migrants arriving from 1907 onwards had introduced anarcho-syndicalism, but it is not clear how much this influenced the Rhondda-based syndicalist Unofficial Reform Committee, which in 1912 launched an influential call for direct industrial action in a pamphlet entitled The Miners’ Next Step.Footnote 183

Communism in the Longwy region did not so much evolve from local traditions as from its Italian heritage. Italian migrants, arriving from about 1900 onwards, originated from the so-called red belt in northern and central Italy, which already had a socialist orientation prior to World War I and later turned to the Partito Comunista Italiano, the PCI. In Villerupt most Italians came from the Marche and Umbria.Footnote 184 Because of those origins, many labour migrants were already left-wing orientated, although only a minority had been expelled or exiled for political reasons: anarchists and revolutionary syndicalists before World War II; communists after the fascists came to power in 1922.Footnote 185 The second generation retained a relationship with their Italian villages of origin.Footnote 186 Successive waves of migration seem to have brought with them different attitudes towards the Church, but ultimately, as in Italy itself, most communist voters in the Longwy region combined participation in Catholic rites de passage (baptism, first communion, marriage, burial) with a non-religious or even anti-clerical attitude.Footnote 187

Conclusion: isolated but embedded countercultures

Historical research on the communist movement has often focused on organizational structures and doctrines, emanating from, or in opposition to, its central command post in Moscow, or on its position within the wider labour movement. Only recently has attention been paid to its diversified structures of support. The French political scientist Frédéric Sawicki has briefly summarized the results of French sociohistorical research of this kind: “Communism did not conquer a near monopoly of working-class representation by imposing its ideology from outside (from Moscow, Ivry [the PCF headquarters], or Rome), but by articulating utopian aspirations constituted and transmitted primarily by trade unionism and other associational activities of workers, but also peasants.”Footnote 188

In this light, the nickname “Little Moscows”, suggesting as it does that small-place communism was just a local reflection of a uniform and universal Moscow-led communist movement, was completely off the mark. Historical and sociological research on the national, regional, and local implantation of communist parties has made it clear that communism has been a social movement of specific moments and specific places. The history of small-place communism shows that it has inspired and activated people to build their own “counter community” at grass-roots level. It is also clear, however, that these could emerge only in very specific local circumstances. I would therefore agree with Julian Mischi, who in his recent study prefers to speak about the structuration locale rather than implantation, because implantation would suggest “an organization coming from outside, from above, to establish, to implant itself in a territory”.Footnote 189 The communist presence in each locality of my sample had specific backgrounds, both historical and structural, and can be explained by a combination of different local characteristics. Following the concept of structuration locale, we should attach more significance to specific local combinations, or an accumulation of causes (in the sense of Gunnar Myrdal), than to a set of uniform conditions.

My approach does not allow one to conclude that the local characteristics identified in this research resulted in communist success in every place in which such characteristics could be found. It can only provide an inventory of possible factors, as a tool for future research in other places and countries. Nevertheless, with this reservation in mind, the examples studied in this article point to interesting commonalities to be found in the structuration locale of communism, which may explain why people in those places were receptive to communist policies and ideas. They can be summarized under three headings: geographical location, socio-economic structure, and past traditions, mostly dating from the period before World War I (Table 2). Some of my places were extremely isolated, in very hostile surroundings. This was especially so in the German cases of Penzberg, Selb, and Mössingen, but also in France in a place like Halluin. In other cases this was less clear: they were situated in an area of more significant communist implantation. However, looking more closely, one finds in these areas too more or less isolated pockets which stood out as exceptional places of communist support. No less than five of my cases were border towns or villages, situated right on the border.

Table 2 “Little Moscows” in western Europe: factors influencing communist implantation.

All the industrial communities in my sample had emerged from small, mostly agrarian villages, or were constructed as completely new settlements. Most of them started to grow around 1890 or 1900. These places were isolated, recently developed, and mono-industrial boom towns, populated by a wave of migrants from the surrounding countryside or by specifically recruited foreign workers, who had formed mono-occupational, pioneer societies. Second-generation migrants turned to communism and built an occupational community based on trade unions and other associations. Most of them had a militant tradition as a continuation of earlier socialism, anarchism, or syndicalism; others had a tradition of irreligiousness or religious indifference. The sudden industrial development (punktuelle Industrialisierung, to quote Tenfelde) of these places had “lifted” them, so to speak, out of the surrounding countryside. These cases exhibited a disruption of social coherence and social control, a characteristic they shared with places in my sample which were significantly detached from the church, or with places at the border where hegemonic pressures were less compared with localities elsewhere.

Interestingly, the turn towards communism by second-generation migrants could happen in different periods, as the French examples make clear. In Halluin it was relatively early, preceding World War I, and culminating in a communist majority just after it. These were second-generation Flemish migrants. In the mining communities in Pas-de Calais, such as Sallaumines, that turn took full effect in the 1930s. These were second-generation migrants from the northern French countryside, and later also Polish miners. In the mining communities in the Longwy region, the communist breakthrough came only at the end of the 1950s and the early 1960s. These were second-generation Italian migrants.

For the second generation, serving in, or simply supporting, the Communist Party and participating in communist-led trade unions and societies offered opportunities to combine political dissociation with social integration, thereby forming what has been called a local counterculture. Theories suggesting that differences in the degrees of social isolation and occupational homogeneity of working-class groups are major factors influencing variations in political radicalism can be valid only for communist strongholds if we consider both trade unions and the other forms of sociability that enabled communists to transform these isolated, mono-industrial or agricultural localities into “occupational communities”.

In this sense, the concepts used in this study, such as punktuelle Industrialisierung (“isolated industrialization”), “occupational community”, “isolated mass”, and “negative integration”, can be considered elements of the explanation, in as far as they refer to the isolated position of the “Little Moscows” in their immediate surroundings. Metaphors used to designate these places – citadelle assiégée (Halluin), Kommunistennest (Penzberg), das rote Insel (Frauenau), and of course the nickname “Little Moscow” itself – illustrate their political isolation and became part of small-place communist identity.

At the same time, the degree of isolation should be seen in the perspective of supra-local relationships, without which local communism would not have emerged. Apart from belonging to an international movement and participating in its national policies, many localities were situated in wider areas of communist support, however unevenly distributed, such as Rhondda East, northern Corrèze, the Longwy region, and the French mining district around Lens. Moreover, the importance of migration in the histories and prehistories of these places indicates that the wider context of social relations cannot be ignored. The way, in the case of the Bugeat canton, migratory workers had established links with Paris, or Italian migrants in the Longwy region were connected with places of origin in the “red belt” of Italy itself, are examples of the importance of these wider relationships, as is the impact of anarchism introduced by migrants, such as Storione in Lumphinnans and Broutchoux (originally from Montceau-les-Mines) in Lens.

The importance of border towns in my sample illustrates the dialectics of isolation and supra-local connections. Their peripheral situation accentuated their isolation from national metropolitan centres, but cross-border connections enabled underground political activities, and also mutual influence, as in the cases of Halluin and Menin in Belgium, the Longwy region and southern Luxembourg, and also in the Czech-German borderlands.

It is still not clear, however, to what extent the different characteristics of the communist strongholds in my sample were exclusive, and how far the factors identified really differentiated these from other communities not susceptible to communism. To reach more substantiated conclusions would require a major collaborative research effort and corresponding resources. It is to be hoped then that this initial inventory will stimulate comparative research on a wider scale, both in Europe and elsewhere in the world.