INTRODUCTION: RE-CONNECTING THE HISTORIES OF NEW CALEDONIA AND AUSTRALIA

In the second half of the nineteenth century, France's colony in New Caledonia and Britain's colonies in Australia were geographically close yet rendered ideologically distant (Figure 1). Observers in the Australian colonies characterized French colonization as backward, inhumane, and uncivilized. The French, meanwhile, although recognizing some fundamental debt to the British in their own penal colonial project, insisted that theirs was a significantly different venture, built on modern, carefully considered methods. In effect, both sides actively denied the comparability of the two penal projects. Historians have perpetuated this culture of distancing and differentiation by neglecting the interconnections that existed between the British and French settler colonies built from convict labour. In this article, I draw attention to the significance of some of the strategies of distance employed in the Australian colonies in relation to the penal colony (bagne) in New Caledonia. Beginning with a discussion of the historiography, I outline the context and contours of convict transportation as penal policy for the British and the French in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Then, I discuss the moral panic in the Australian colonies about the dangerous proximity of New Caledonia, as presented in Australian newspapers, which included arguments about the need to monitor and restrict the mobility of suspect populations. In the final section, I argue that these efforts to control physical mobility were accompanied by constant discursive attempts to emphasize the ideological distinctions between the British and French colonial possessions, which, at the same time as buttressing Australian colonial claims to self-government, also tied them more closely to the British world. In sum, this article contends that discussions of the New Caledonian bagne, at a time when the Australian colonies sought recognition as reputable settlements of morally upright populations, both emphasized the French penal colony's geographical closeness to Australia and its ideological distance. These strategies of distance acted as effective means by which the penal origins of British settlement in Australia might be safely quarantined in the past.

Figure 1. Map of Australia and New Caledonia.

As penal and settler colonies, Australia and New Caledonia share remarkably similar and, indeed, closely interwoven histories, yet historians have neglected to examine their interconnections. Several decades ago, historians lamented the tendency to characterize coerced migration to Australia as “an aberration” and called for greater attention to be paid to the comparative experience of penal colonization in Australia, French Guiana, and New Caledonia.Footnote 1 These calls have remained largely unanswered. Recent scholarship examining New Caledonia directly through the lens of settler colonialism omits its relationship to Australia.Footnote 2 Historians have explored France's early fascination with Britain's Australian experiment,Footnote 3 but little attempt has been made to study the strange synchronicity of France's incorporating convict transportation into its penal-colonial repertoire at the very moment that Britain, under the force of resistance by settlers in Australia and the Cape Colony, was gradually abolishing it.Footnote 4 This arresting conjuncture, however, exposes some important dynamics of penal colonization and settler colonialism. Australia's panic about escaped French convicts and resultant diplomatic altercations are not unknown. The topic received scholarly attention at least as early as the 1950s.Footnote 5 More recently, fruitful analysis has set the phenomenon within the context of Australian nation-building agendas in the decades leading up to Federation in 1901, when Australia's six colonies were granted self-government as part of the Commonwealth of Australia.Footnote 6 These recent studies have situated the moral panic about French convicts as “part of a larger story of post-convict shame”.Footnote 7 I have pointed out elsewhere that this contrasted with the explicit engagement with the problem of New Caledonian convicts and constituted an act of projection on the part of Australian colonists.Footnote 8 While interactions between Australia and New Caledonia on the issue of French convicts have been examined, the basis for and implications of denying foundational ideological similarities have been largely overlooked. Here, I extend these existing studies and introduce a more dialectical analysis, examining how arguments about controlling the mobility of French convicts fed into ideological narratives about the origins of British settlement in Australia, and presenting a wider argument about discursive and legislative strategies of distance and disassociation. Rather than analysing state-level diplomatic exchanges, the focus here is on how French convict transportation and penal colonization were presented to the newspaper-reading public in the Australian colonies.

Research into imperial history continues to expand,Footnote 9 sensitivity to cross-imperial exchange and mobility deepens,Footnote 10 but historians have yet to explore connections and relations that existed (or, indeed, were denied) between colonies controlled by different foreign powers.Footnote 11 Recent work highlights “imperial careering” in the construction of the British Empire, but work remains to be done on how one colonial power's imperial knowledge was taken up by another.Footnote 12 Research spearheaded by Clare Anderson, in particular, has expanded understandings of the global patterns of convict transportation, but the specifics of how one state explicitly invoked the practice of another remain considerably understudied.Footnote 13 Isabelle Merle's perceptive observation that “the geographical distance that separates Sydney from New Caledonia is historically very great”Footnote 14 inadvertently reinforces nineteenth-century observers’ arguments of incommensurability, masking broad ideological continuities between European settler colonies built from convict labour. Assertions of exceptionalism are, of course, a standard posture in imperial regimes’ official discourses.Footnote 15 Two central contributions of this article to the existing historiography are, firstly, its analysis of the Australian colonies’ active denial of equivalence with New Caledonia, which served strategic political ends, and, secondly, its contextualization of these questions within the frame of international criminal justice reform and imperial expansion agendas in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Between 1787 and 1868, over 167,000 male and female convicts, many of them young, were transported from the British Isles to Australia.Footnote 16 From 1864 to 1897, France sent more than 23,000 prisoners to New Caledonia (Figure 2).Footnote 17 For both European powers, convict transportation had a dual purpose – cleansing the metropole and expanding imperial holdings by putting convicts to work. This dual purpose, however, produced tensions at the system's very heart: economic returns of coerced labour were undercut by the expenditure required to transport convicts to the antipodes. In duration and scale, the New Caledonian bagne was dwarfed by both Britain's penal project in Australia and by France's other overseas penal colony in French Guiana.Footnote 18 Contemporary observers and historians in their wake subjected French Guiana to greater scrutiny than the penal colony in the South Pacific.Footnote 19 Even when interest in New Caledonia was shown in the French metropole, it was overwhelmingly focused on Communards’ experiences. From 1872 until the amnesty in 1880, Communards were exiled to the Isle of Pines, an island southeast of the Grande Terre, while the political prisoners considered more dangerous (among them Henri de Rochefort and Louise Michel) were held on the Ducos Peninsula (Figure 3).Footnote 20 With only the rare exception (i.e. Michel, who, after being transferred from Ducos to the Isle of Pines, embraced Kanak culture),Footnote 21 the Communards portrayed their exile as utter desolation.Footnote 22 After the amnesty, some, among them the artist Lucien Henry, elected to settle in Australia.Footnote 23 The overwhelming majority, however, returned to France.

Figure 2. Allan Hughan, ‘Le boulevard du crime, 1877’. Bagne at Île Nou, New Caledonia.

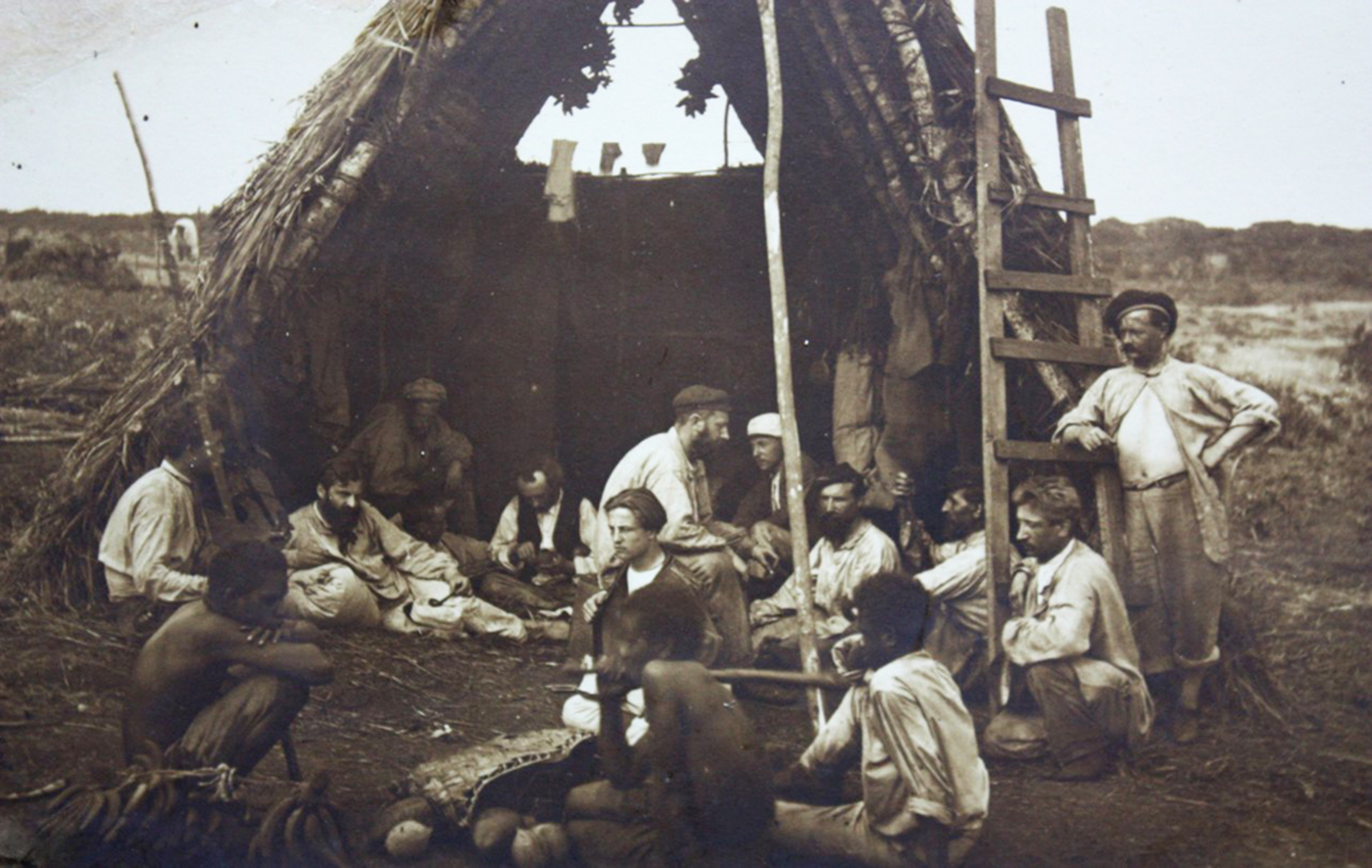

Figure 3. Allan Hughan, Encampment of Deported Communard Prisoners, Île des Pins, New Caledonia, private collection.

From its earliest years, Britain's penal colonial project in Australia fascinated the French, producing a mythology about “Botany Bay”.Footnote 24 Colin Forster invokes the “anachronistic air” of France's decision to adopt “such an ambitious penal venture so late in the day” – decades later than the British and precisely when Australian colonists, asserting their right to self-government, were demanding transportation's abolition. In positioning the French as Britain's backward heir, Forster insinuates that their project was doomed to fail. With his gaze firmly directed backwards, Forster traces the genealogy of France's introduction of penal colonization and leaves untreated the history of the bagne in operation.Footnote 25 Such a choice implies that the French project was dead in the water, perpetuating arguments repeatedly posited by nineteenth-century observers about the backwardness of the bagne relative to British settlement in Australia. In a context in which the Australian colonies were eager to assert their deservingness of self-government, this characterization was expedient, helping to create a point of rupture with Australia's own convict past and thus facilitating the Australian colonies’ claims to a more respectable system of social organization and a more legitimate birth as a settler colony than their French colonial neighbours.

As colonizer of distant territories using convict labour, Britain was attributed the mantle of pioneer by the French. In truth, however, in banishing convicts and requiring them to perform labour as a condition of their sentence, the British were following a lead set by foreign powers. Historians have begun to address this longer history of convict transportation, situating it along “a continuum of coerced labour and migration, […] enslaved labour, indentured contract work, military and maritime impressment, and indigenous expropriation”.Footnote 26 For centuries, Russia had transported convicts to Siberia for the purposes of colonization, and between the sixteenth and the mid-eighteenth century, hard-labour convicts in France were put to work as galley-ship rowers and later in port city bagnes.Footnote 27 For decades before convict transportation to Australia, Britain's parliament rejected detention with hard labour on the grounds that this French practice was tyrannical and antithetical to British liberty. The loss of the American colonies and the resultant overcrowding of metropolitan prisons in the 1780s, however, propelled Britain's lawmakers to pass the, ostensibly temporary, “Hulks Act” inaugurating forced labour (in naval dockyards) in the criminal justice system. With the door prised open, forced labour was applied to convicts transported to Australia from 1787 onwards. Into the nineteenth century, against reformers like Elizabeth Fry who insisted on detention's rehabilitative purpose, proponents of convict transportation asserted the system's humanitarian ends and its regenerative capacities, in addition to its clear advantages for public safety in the metropole, which would be of moral and economic benefit, both individual and collective. Transported prisoners would be transformed into hard-working, productive settlers.Footnote 28 Transporting convicts beyond the seas had a clear social control function in protecting the metropole from unruly populations, but the system also had a clear economic utility. In France, this was foregrounded by Napoleon III. Prior to the passage of legislation in May 1854 and amid growing opposition to the bagnes in French port cities, Napoleon argued that transporting convicts to colonial territories would make it “possible to render the punishment of hard labour more effective, less costly, and, at the same time, more humane, by using it for the advancement of French colonisation”.Footnote 29

DENYING COMPARABILITY

To most mid-nineteenth-century French penal reformers, and indeed to their international colleagues, convict transportation smacked of exploitation. They were adamantly opposed to it, preferring penitentiaries, whose proximity to political centres of authority made them more readily regulated mechanisms for prisoners’ humanitarian reform and long-term social defence. Among the international community of penologists, meeting regularly by century's end, France was viewed as outmoded in continuing to practise transportation.Footnote 30 As Clare Anderson has recently pointed out, historians, following Michel Foucault's lead, have tended to emphasize the penitentiary as the dominant modern penal practice without paying due attention to the persistence of transportation to penal colonies, or, indeed, to its importance in helping to shape practices in the metropole.Footnote 31 While the abolition of British convict transportation to Australia mid-century adheres to Foucault's schema of the rise of the modern penitentiary, France's synchronous introduction of convict transportation sits less neatly. Moreover, although France was singled out for particular discussion at the International Prison Congress in the mid-1890s, it was not the only Western power to engage in late-phase transportation; Russia, Portugal, and Spain all increased their shipments of convicts overseas in the latter part of the nineteenth century.Footnote 32

Among international penal reformers, however, advocates of transportation were vastly outnumbered. In an attempt to solidify their endorsement of convict transportation from a moral and reformative perspective, champions of French convict transportation appealed to Australia's success as a flourishing colonial holding. Advocates further pointed to Australian colonists’ rejection of further shipments of British convicts as evidence of the system's regenerative efficacy.Footnote 33 In 1863, as news that French convicts were finally set to be transported to New Caledonia, the Sydney Morning Herald commented that “we can claim to have great experience, and to be in a position to judge more truly what may be the probable result from a French point of view”, declaring that:

We have the strongest possible impression that no successful colonisation will ever be accomplished through the interposition of convict labour in proportion to its cost and to its waste of life in proportion to the social mischief which accompanies it, and that it is more likely (except by adventitious circumstances) to permanently destroy than to advance the settlement of a new country.Footnote 34

In 1884, as French statesmen debated a bill on transporting recidivists, the Herald dispatched a “special commissioner” to file reports on New Caledonia and its penal settlement. The journalist wrote that, in sending convicts to distant territory, France was “re-attempt[ing] an experiment which has been made time after time by ancient as well as modern nations, and always – without one exception to set against the experience – with absolute and indisputable failure”.Footnote 35 Any allegation that New Caledonia had been modelled on Australia was undermined by this observation that Britain was far from alone in having employed the practice. In a subsequent piece, the journalist wrote that Australian colonies had only flourished when convict transportation was suppressed.Footnote 36

This argument was reinforced a few months later in the same newspaper by Howard Vincent, London's former Director of Criminal Investigation, who stated that France's decision to transport its convicts to New Caledonia “had its basis, doubtless, in the popular delusion among Frenchmen that such prosperity as they hear credited to Australia is due to the early system of transportation to some of the colonies”.Footnote 37 Colonization, however, it was argued, could only truly develop through free migration. In 1890, the Melbourne weekly newspaper Leader argued that “New Caledonia, both from a colonising point of view and as a reformatory for criminals, is confessedly a failure” and “Australian experience offers no encouragement to the idea that a free and prosperous civilisation can be established on a rotten and criminal foundation”.Footnote 38 New Caledonia thereby served as a powerful negative example of penal colonization, enabling the Australian colonies to assert their own relative superiority and arguably helping to foster a feeling of closeness to Britain and a “sense of colonial connectedness”.Footnote 39

Within Australia in the second half of the nineteenth century, resisting an influx of convicts – no matter their provenance – was viewed as an important means for building respect from Britain. In 1874, Melbourne's Argus asserted that the Australian colonies were entirely justified in complaining to France about New Caledonia's use as a convict depot:

Great material sacrifices have been made by two at least of these colonies [i.e. New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land] to get rid of the convict taint which formerly attached to them, and to avoid the odium they had thus incurred in the estimation of their own countrymen at home. The injurious impression originally produced upon the English mind has been gradually effaced, and may now be considered to have altogether disappeared. But it will be revived among Europeans generally if the neighbouring islands of New Caledonia are to become the égout collecteur for the criminal filth and feculence of France; Australia will be once more associated with convictism, and such association cannot fail to be most detrimental to our reputation and inimical to our progress and prosperity.Footnote 40

Similarly, in 1884, in response to the prospect of French repeat offenders being transported, the Argus declared that “the more determined our resistance to foreign convictism, the more we earn the respect of Englishmen at home”.Footnote 41 While the French tended to claim a shared heritage with Britain's penal colonization, Britain and its Australian colonies sought to distance themselves from their self-proclaimed heirs. Indeed, the Australian colonies activated a conscious programme of discrimination, introducing ever more precise border control measures to restrict New Caledonian transported convicts, monitoring anyone suspected of a connection to the bagne.

Circumnavigated by both James Cook in 1774 and Antoine Bruni d'Entrecasteaux in 1792, European influence in New Caledonia remained limited until 1840. When Britain sent convicts to Australia in the late eighteenth century, the territory's extreme isolation from Europe and its unmapped interior had made the erection of prisons and walls unnecessary. For convicts, the distance from the metropole and the wildness of the Australian bush acted as natural deterrents against escape: to flee the colony was to disappear into the great unknown.Footnote 42 Convicts transported to Australia were not explicitly barred from returning to the mother country once their sentence had been served. So isolated was Australia from Britain at the moment of first European settlement, any such provision presumably seemed superfluous. By the time that France established its penal colony, the entire region had been brought into a relationship with Europeans; New Caledonia's contours had been explored and mapped and, although internal access was largely undeveloped, routes across the seas were well established. Disappearing internally into the New Caledonian bush was possible but more limited, so much smaller was the territory. The statistics on the rate of recapture of escapees from the bagne are very telling: between 1864 and 1880, more than three quarters of all escapees were re-apprehended, and between 1896 and 1900 that figure had risen to almost nine tenths.Footnote 43

French advocates of convict transportation held a rather ambivalent attitude to the Australian model. While admitting a basic conceptual debt to the British, they rejected substantive similarities, arguing that whereas the British in their experiment in Australia had constantly felt their way along, theirs was a rational, pre-conceived system. The British, they maintained, may have been the pioneers, but their methods were experimental.Footnote 44 Commentators in Australia similarly denied any shared characteristics with the New Caledonia colony. The incapacity of its governors and the incompatibility of the French way of life with migration were a constant refrain among observers in the Australian colonies. The French were too careless, inept, and immoral to be able to colonize – a situation that further threatened Australian colonial society since, it was argued, rather than remain in the mismanaged French colony, prisoners would opt to escape to Australia either while under sentence or on receiving their freedom. Even with good management French colonialism was severely hampered by a perceived reluctance among the French to emigrate. Unlike other Europeans, especially Germans or Italians, French people would not readily volunteer to uproot themselves.Footnote 45 Amid discussions about competition for control of New Guinea, Melbourne's Australasian claimed that Britain's rivals lacked any flair for successful colonization, remarking that “It is idiotic to talk of France, Germany, or Italy as a colonising nation; none of them ever has been in the real sense of the word, or ever will be, a colony-planter.”Footnote 46 Sydney's Evening News in 1897 commented that the French had “no desire to wander, none of the Anglo-Saxon restless spirit of exploration”.Footnote 47 French people's unwillingness to migrate to distant territories led foreign observers to argue that France had greater need for coerced forms of migration in order to build up its imperial holdings, and French advocates of transportation argued that the people's close attachment to the patrie made coerced migration all the more terrifying and all the more necessary.Footnote 48 French people's aversion to free migration was confirmed by the fact that five years after New Caledonia was claimed, Australians were being headhunted by the French to colonize and cultivate the land.Footnote 49

Criticisms in Australia of French methods of colonization extended to the very process of annexation of New Caledonia in 1853. Although France's claiming of the archipelago was considered audacious, the state's right to claim sovereignty was not disputed. Nonetheless, the fact that France had simply annexed the territory rather than conquering it through warfare or securing it through a treaty was considered improper. This, coupled with the fact that the French had not been responsible for having first “discovered” New Caledonia in the late eighteenth century, led to a perception of France as having breached the “law of civilised nations”.Footnote 50 Decades later, following the 1878 Kanak revolt, commentators pointed to French ineptitude and insensitivity in provoking the Indigenous people's rancour and violence. In one of a series of on-the-ground dispatches on “The War in New Caledonia”, a Herald correspondent commented on the Kanak people's cooperativeness, attributing it to the “fact that Englishmen or Australians in New Caledonia have always treated the natives better than the French”.Footnote 51 A few months later, another article noted that although “throughout this struggle public sympathy in these [Australian] colonies has naturally been on the side of the colonists” there was if not justification, then “ample excuse for the native revolt”. The “unscrupulous and meddlesome French colonists” failed to respect the basic principles of colonial diplomacy with indigenous peoples. Casting British colonial rule as benevolent exemplar, the journalist concluded that the French had “much to learn before they are likely to become successful colonizers in the South Seas”.Footnote 52

CONTROLLING MOBILITY: FRENCH CONVICTS ON THE MOVE

As early as November 1853, when news of France having claimed New Caledonia first reached Australia, the alleged dangers posed by a proximate French colony became a recurrent topic of discussion in newspapers. Reports focused not only on France's audacity in laying claim to the archipelago, but also on the perceived humiliation to the Australian colonies produced by Britain's inattention in allowing the seizure to occur.Footnote 53 Although New Caledonia would not serve as a penal colony for the French until the 1860s, the prospect of this was planted early in the minds of Australian readers. In November 1853, two months after Admiral Auguste Febvrier-Despointes officially claimed the archipelago for France and one month before Britain abolished transporting convicts to Van Diemen's Land (present-day Tasmania), the Sydney Morning Herald told readers that

We have reason to believe that the immediate object of the French government is to establish a penal settlement on the island […] [and] we cannot refrain from expressing our deep regret that, by the laxity of the British Government, notwithstanding the repeated and earnest representations which have been made to it […] the opportunity of colonising that fine group has been lost. That regret is enhanced by the consideration that after all our struggles to get rid of the withering curse of convictism, after the bitter differences which had arisen between the colonies and the mother country have been happily reconciled by the total abandonment of transportation to these shores, a convict settlement should be formed by a powerful foreign nation in our immediate neighbourhood.Footnote 54

The implications were made clear; while acknowledging that Sydney might reap some commercial benefit from New Caledonia's colonization

even by the French […] such a consideration […] sinks into insignificance by the side of the moral, social, and political consequences attaching to the occupation of one of the most splendid islands in the Pacific by a rival nation, whose aims and objects are so dissimilar, not to say opposite, to those which have for many years been earnestly contemplated by the most intelligent colonists of Australia and New Zealand.Footnote 55

The following day, a Herald reader wrote that “Whatever may be the surprise created by this recent act of the French Government, upon reflection the cause is patent […] British energy thwarted by Downing-street apathy, has allowed New Caledonia to become a French Penal Settlement, instead of a British colony, free from that curse.”Footnote 56 Another article pursued the issue with greater fervour: “No sooner […] have we got rid of British convictism than we are threatened with French convictism.”Footnote 57

As the years went by, and while the islands had not become a settlement for French convicts, Australian newspapers regularly peddled stories about the risks posed by a potential penal colony located so close to Australia's east coast. Attention focused particularly on the risk of escapes from the bagne. Less than 1,500 kilometres to the east of Australia (about 730 nautical miles), New Caledonia was a relatively short journey from the Australian colonies, and significantly less than the distance separating the Swan River Colony near Perth in Western Australia from the more settled east coast. New Caledonia was said by Australian journalists to represent a dangerous proximity, the Coral Sea's hazardous conditions and perilous reefs were downplayed, considered no match for resolute prisoners desperate to escape their island prison. When New Caledonia was finally confirmed as a site for convicts in 1863, newspaper reports articulated outrage. The Sydney Morning Herald observed that coerced migration to a penal colony made sense to the French because as a people they lacked the entrepreneurial and voluntarist spirit necessary for the successful free colonization of distant lands. Penal colonization would not, however, produce a healthy settlement and the effects of this for Australia would be significant: “as the criminal population of New Caledonia becomes ripe for discharge, we may expect that large numbers of them will seek a home in the colonies of England. This will, of course, bring the question practically to our doors”.Footnote 58 The Australasian, which described New Caledonia as “an island so near to Australia as to be almost a part of it”, expressed a preference for “a Bengal tiger [to be] loose among our women than genuine French ‘Forcat’ [sic] from the Bagnes of Brest or Toulon, for the tiger could only take life, and the galley slave would take life and something else”.Footnote 59

When the first shipment of convicts arrived in New Caledonia in 1864, paranoia in Australia had thus already long been prepared. The anxiety adheres to the contours of a classic moral panic, as defined by Stanley Cohen.Footnote 60 New Caledonia – “the modern Pandemonium of the Pacific”Footnote 61 – aroused coverage and commentary from newspapers throughout the country; in original and syndicated form, newspapers in urban, provincial, and rural areas all drew attention to the alleged dangers posed. A basic and sustained anxiety about French convicts could not have been the creation of newspapers alone; in order to get traction, a phenomenon identified as problematic must dovetail with an existing concern to which the media then gives definition, meaning, and scale.Footnote 62 Firmly rooting this moral panic were its origins in tensions between the Australian colonies in the first half of the nineteenth century deriving from whether they had been founded by convicts or free settlers. After formal abolition of transportation to New South Wales in 1850 and Van Diemen's Land in 1853, this manifested primarily as a concern about the dangers of free movement of transported (British) convicts between Australian colonies. From here, it would be a short step to seeing French convicts as equally dangerous. Convicts on the move were the subject of “blame gossip”, serving as a useful scapegoat for any instability within colonial society.Footnote 63

While divisions emanating from British convictism would not entirely disappear, the French threat largely overtook it as a preoccupation. Importantly, resisting French convictism became a way that the Australian colonies, with or without convict histories, could assert their own probity. For some French, the colonies’ very resistance provided further evidence of the success of the system.Footnote 64 While legislation relating to British convicts on the move pitted the Australian colonies against one another, the issue of French convictism had greater potential to unify them – something that would appeal to interest groups pushing for the Australian colonies to federate. As the years went on, police in Australia were called on to monitor and report on the presence and activities of any person residing in their jurisdiction suspected of having ever been detained in the New Caledonia colony.Footnote 65 Until well beyond the quiet suspension of transportation of convicts in 1897,Footnote 66 the French settlement was viewed from Australia with intense distrust. At the same time that authorities were making efforts to control the movement of former convicts between the Australian colonies and similarly to restrict the movement of Chinese, they sought to monitor the mobility and migration of French prisoners from New Caledonia.Footnote 67

As cases of French convicts reaching Australia materialized from the 1860s onwards, the long-standing latent danger of infiltration was seen to have finally eventuated. In 1866, concerns about Australian border security were raised in relation to a case of French convicts who absconded from the vessel docked in Sydney Harbour that was transporting them to New Caledonia. At that time and until the mid-1870s, the absence of extradition arrangements between France and Britain limited the capacity for colonial authorities in Australia to intervene in such cases, provoking frustration and alarm.Footnote 68 As further New Caledonian escapees arrived in Australia in the 1870s, journalists were quick to point out the inevitability of such events.Footnote 69 In keeping with Cohen's model of the moral panic, the arrival of one boat was not read as a rare occurrence, but rather as a harbinger of a much greater problem.Footnote 70 At this time, the more geographically proximate French convict settlement, which from the early 1870s received participants from the Paris Commune, was seen as a greater threat to the (emancipated) eastern colonies of Australia than the British convicts of Western Australia.Footnote 71 Arrivals, among them a group of Communards including Henri de Rochefort in Newcastle in 1874, were noted by journalists and status-conscious public statesmen expressed concern about their destabilizing effect.Footnote 72

The anxiety was intensified in the 1880s when French recidivists were added to the archipelago's population. The Sydney Morning Herald condemned France's decision to carry on “the practice of shooting more of her moral rubbish in close proximity to our shores”.Footnote 73 In response to France's wilful polluting of areas close to Australia, the Colony of Victoria's chief secretary called for the Australian colonies to unite as a federal council, asserting the greater dangers posed to the free Australian colonies by French convicts’ border breaches than by West Australians. Although convicts from Western Australia had been “degraded, [they were] at least of the same blood and same language as ourselves”, which made them easier to control than foreigners.Footnote 74 Opposition to French convicts was thus invoked in processes aimed at building a sense of common interests between the Australian colonies. The steady stream of critical rhetoric about the French penal settlement and the need to protect Australian colonial society from exposure to its populations effectively served to foster a perception of ideological distance between these European settler colonies – a useful strategy for imagining a proto-national community and building social bonds between the disparate inhabitants of the Australian colonies, a component of which entailed emphasizing their common moral rectitude.Footnote 75 As recent research has suggested, opposition to and differentiation from New Caledonia contributed to the solidification of a sense of Australian nationalism, especially in the 1870s and 1880s, as part of a climate of imperial competition for territory in the South Pacific.Footnote 76 In 1880, Adelaide's South Australian Register reflected on the objections raised to the establishment of the French penal colony decades earlier and concluded that “experience has proved that the danger apprehended was not imaginary. More than one party of prisoners has found its way to New South Wales, and although, owing to increased precautions, there have been no recent escapes, it is impossible to say how soon fresh relays of criminals may discover means of reaching Australia”.Footnote 77 Into the 1890s, this sense of nationalism took on racial overtones as a moral panic about an Asian invasion took root, part of a longer anti-Chinese immigration campaign that culminated in the White Australia policy of 1901.Footnote 78

Although commentators focused on the latent and actual dangers posed by the physical closeness to the French penal colony, there was a deeper aspect of propinquity. To some degree, the New Caledonia penal colony constituted a “return of the repressed” for the Australian colonies, reminding them of their own convict origins. Rather than accept any similarity, the Australian colonies preferred to scapegoat the French. Indeed, despite the protestations about the presence of a penal colony on their doorstep, the existence of that reminder was not altogether unwelcome or without utility as it bound the Australian colonies together, just as the issue of domestic convictism tended to drive them apart. For instance, shortly after its creation, the Colony of Victoria asserted its distinction from New South Wales (from which it had issued in 1851), and protected its status as a free society by passing the Convicts Prevention Act to prevent the entry of convicts without a ticket-of-leave (which indicated that they had served their full sentence).Footnote 79 In ensuing years, this legislation was further extended. The primary target was convicts from Van Diemen's Land likely to be attracted north by the prospect of striking gold, but Western Australia, which officially began receiving convicts in 1850, also became a concern.Footnote 80 In 1863, representatives from the anti-transportation Australasian League in New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania petitioned Queen Victoria to abandon sending convicts to Western Australia in the interests of the general welfare and prosperity of the surrounding colonies.Footnote 81 That same year, New Caledonia became part of France's penal portfolio, replacing French Guiana, whose tropical conditions had proven deadly, and in May 1864 the first convoy of hard-labour convicts disembarked (Figure 4). For the most part they would be held on the Île Nou, an island off the west coast of the Grande Terre (New Caledonia's main island) (Figure 5).Footnote 82

Figure 4. ‘The French Transport Ship L'Orne – Caged Prisoners’, Illustrated Sydney News and New South Wales Agriculturalist and Grazier, (NSW: 1872-1881), 10 June 1873, p. 5. National Library of Australia. Available at https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/63619442

Figure 5. Samuel Calvert, ‘The Convict Settlement, Isle of Nou, New Caledonia’, print (wood engraving), published in Illustrated Australian News for Home Readers, 22 April 1873. State Library Victoria. Available at: http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/241643

The New Caledonia convict threat encouraged the Australian colonies to rise above internal divisions derived primarily from questions of whether they had been founded by convicts or free settlers. The Colony of South Australia, as the South Australian Advertiser reminded its readers (in February 1872 in the context of plans by the French to transport Communards to New Caledonia), had “always protested against convicts from the penal provinces being permitted to land [there]”. “We have been anxious”, the article continued, “to keep the land free from the convict taint, and hitherto we have been successful”.Footnote 83 The Colony of Victoria had identical aspirations. In November 1854 – the same year that France formalized its convict transportation legislation – the Legislative Council of Victoria passed an “Act to Prevent the Influx of Criminals into Victoria”, empowering colonial authorities to arrest any person reasonably suspected of having been found guilty of a felony or transportable offence in Britain or any British possession.Footnote 84 This legislation was primarily aimed at preserving Victoria from the “taint” of British convictism emanating from Van Diemen's Land.Footnote 85 Although the persons from whom Victorians sought to preserve themselves were distinguished by being convicts, they were nonetheless British subjects, which as time wore on would become a more salient element of identity than their criminal backgrounds. In the second half of the nineteenth century, this existing fear of the (British) transported convict was transposed onto the French. These debates intersected with the stringent restrictions in place for Chinese immigrants. In 1879, Hobart's Mercury newspaper observed that there was much talk about Chinese contagion and a poll tax in place to control it, but little being done about the French. Endorsing an observation recently made in Sydney, The Mercury commented that although New Caledonian immigration to Australia was smaller numerically than Chinese, the threat it constituted was great.Footnote 86

The following month, the Sydney Morning Herald printed extracts presented to the New South Wales Legislative Assembly from documents “having reference to the influx into New South Wales from New Caledonia of persons who have been deported thither as convicts by the Government of France”, opening a window onto the inter-colonial communications between the Australasian colonies (New Zealand included). In August 1876, Sir John Robertson, Premier of New South Wales, telegrammed the Chief Secretaries of other colonies inquiring whether laws existed to prevent pardoned “Communists” from entering their respective colonies and expressing his conviction that “the Australias should unite in a remonstrance, which I have reason to believe France will respect”.Footnote 87 New Zealand, Queensland, Tasmania, and Victoria all replied that no such legislation existed. South Australia's Chief Secretary pointed to that colony's “‘Law Convicts Prevention Act’, No. 9 of 1863; amended by No. 14 of 1865”, but this act only applied to British colonies or possessions. Moreover, the South Australian representative pointed out, such legislation only had purchase for common law offenders, not political ones.Footnote 88 In June 1879, the NSW Legislative Assembly debated “A Bill to Make Provisions Against the Influx of Certain Foreign Criminals into New South Wales”, primarily directed against Communards. The bill failed to pass on its second reading and its purpose was rendered redundant in any case after the granting of amnesty to Communards in 1880.Footnote 89 In 1887, Melbourne's Weekly Times reported enthusiastically that the New South Wales Parliament was debating a foreign convicts bill (it did not pass).Footnote 90 In April 1896, a newspaper from the goldmining town of Bathurst encouraged New South Wales to adopt legislation preventing entry to foreign convicts, arguing that colonies should only have to deal with their own criminals – “New South Wales should be confined to the consumption of its own smoke only”.Footnote 91

CONCLUSION

As neighbouring European settler colonies, New Caledonia and Australia were marked by simultaneous forces of closeness and distance. In the 1880s, a journalist described the profound culture shock experienced travelling from Australia to New Caledonia: “It is the greatest possible change an Australian can have. In five days from Sydney he lands in a foreign country, under foreign laws; he listens to a foreign language, and lives according to foreign habits.”Footnote 92 There is in these words a clear sense of New Caledonia's exoticism and an implicit neglect of the obvious equivalence between the French settler colony employing convict labour and the Australian colonies. The opposition to the establishment of a French penal colony contiguous to Australia was a natural extension to the existing anti-transportation campaigns directed against Britain, but it also served a further purpose: asserting outrage was a mechanism for the Australian colonies to underline the rupture between the past of penal colonization and the present (and future) of free settler colonialism. It was, in short, a tool of disassociation. The opposition to the transportation of convicts to the Australian continent or its immediate neighbours effectively reinforced the notion that traces of the convict system were only to be found in the individuals transported and their descendants and not in the system of governance itself. Indeed, the degree of virtue of free settler governance was located precisely in its distance from the convict taint. Through a reflection on the constant and vociferous protestations from certain quarters in the Australian colonies about the contaminative dangers posed by a population of foreign miscreants residing so close, the New Caledonia bagne served a powerful symbolic and discursive function for the Australian colonies, ultimately acting as a vehicle by which the convict foundations of British settlement could be negated.

New Caledonia played an important role in the Australian colonies’ transition to self-government in the nineteenth century, a process that entailed the conscious dispossession of Indigenous AustraliansFootnote 93 and, as I have argued elsewhere, helped to legitimize British settler authority by casting it as superior to the French.Footnote 94 In important ways, the focus on the scourge of French convictism served to further reinforce the notion that convictism was a curse of foreign origin, which, through colonial resistance, had left no lasting negative effects on colonial society and that overwhelmed to the point of silence any consideration of Indigenous presence. The proximity of the French penal colony was said to threaten efforts in Australia to build a morally respectable settler society, which could, in turn, jeopardize the colonies’ chances of gaining greater administrative self-government from Britain. In effect, whether embodied as an actual threat because its prisoner populations were on the move, or constituted as a looming latent danger, New Caledonia could be mobilized as a scapegoat for introducing division or instability within the Australian colonies. Convictism was portrayed as fundamentally a system which had no substantive influence on power relations within the colony and thus could be transcended simply by “turning off the dirty water tap” beyond the colony's borders.Footnote 95 So long as that flow was kept closed off at the source, the convict system would remain safely in the past. This convenient, self-exculpatory theory offered a means of avoiding the more difficult business of thinking through how the penal period had affected the Australian colonies structurally; for instance, in terms of policing.Footnote 96

The waters separating Australia from New Caledonia acted redemptively, enabling past sins of white Australian settlement to be cleansed,Footnote 97 while New Caledonia itself became effectively a lieu de mémoire décalé for the Australian colonies, a space of projection that facilitated Australian settlers’ active rejection of their own origins.Footnote 98 In addition, Australian observers’ allegations of French misrule – both in terms of management of convicts and relations with Indigenous peoples – cast into shadow the violence of forces of settler colonialism in Australia. France's penal colonial settlement could become a vehicle for asserting the relative respectability and rootedness of British settlement; a means through which the penal phase of settlement and its bloody dispossession of Aboriginal people might be quarantined safely in the past – despite the violent conflict still ongoing in this period in many parts of Australia. In their standard discourse on New Caledonia, the Australian colonies produced a distorting perspective: constantly portrayed as dangerously close in geographical space, this effectively made the French penal colony reassuringly distant in “civilizational” development, and thus also – importantly – ideologically dissimilar.