INTRODUCTION

In the eighteenth century, the Russian Empire experienced rapid economic growth and a significant transformation of its social structure. With the country’s industrialization and the modernization of the military sphere, it became one of the world’s leading powers. This geopolitical success was backed by a significant demographic expansion (with the population increasing from 10.5 million in 1678 to 38 million in 1795, owing both to natural growth and the acquisition of new territories),Footnote 1 followed by massive migration and the rapid agricultural development of the frontier regions, especially in the southern and eastern steppe borders of the empire.

It is fairly clear, however, that the mechanisms used to achieve these results were significantly different from those of West European countries, where the development of markets, growth of industry, and rapid urbanization led to the decline of mediaeval estates and fostered a specialization of labour. An abundant historiography, both Soviet/Russian and Western, focused on the economic issues of that period, generally agrees that market institutions, especially the labour market, developed significantly less than in Western Europe,Footnote 2 and the role of estates in the ordering of society remained important and actually grew.Footnote 3 The question arises, then, as to what instruments were used by the state to substitute the market mechanisms.

In terms of the history of labour, this outlines the need for the advanced study of the relations identified in the Collaboratory taxonomy as tributary.Footnote 4 As a rule, such direct obligations were described as sluzhba (service) or povinnosti (duties). They were widespread in Muscovy, being directly linked to landowning: “all men should bear service from their land, and no one should own land gratuitously”, the decree of 1701 stated.Footnote 5 In the eighteenth century, the direct link between landowning and obligatory service was broken for the nobility, as in 1714 Peter I proclaimed service to be obligatory for all nobles, regardless of their land possessions, and in 1762 Peter III abolished obligatory service but left landowning untouched. For the large non-noble groups within the population, however, the system of obligatory works and services imposed by the state continued to be very important from both an economic and a social point of view. We will address this later in this article, when we discuss the factors behind the emergence and enduring nature of these relations.

We focus on the eighteenth century, which was critical for the history of the territorial expansion of Russia as it was a period when the broad belt of southern and eastern border regions became safe and started to attract large migration flows; it was also when the paradigm of the interaction of the state with its subjects significantly changed, and the newly established imperial administration began to actively shape social structures and labour relations. To a large extent, the framework of relations between the imperial administration and the estates, elaborated in the course of the eighteenth century, continued to exist until the end of the imperial period.

SOURCES AND DATABASE

Fortunately, the Russian Empire in the eighteenth century had an advanced system of population statistics. The poll tax was the key element in the country’s financial system and, to this end, periodic taxpayers’ registries, so-called revizias, were compiled approximately every twenty years, in 1719–1724, 1744, 1763, 1781, and 1795.

This article primarily addresses the large database (over 400,000 records) that is one outcome of the Collaboratory. It covers the project benchmark for 1800, based on the fifth revizia (1795).Footnote 6 Being one of the world’s most accurate censuses at the time,Footnote 7 it covers nearly the entire population of the empire, organized by provinces and social groups, and provides a solid ground for comparison and retroactive estimates.Footnote 8 The system of social stratification in the late eighteenth century was quite multi-layered, and each social group was identified according to its position in society and its obligations to the state. Some of them can be found in all regions (like state peasants), others existed only in several provinces, or just one. Drawing on the historiography and legislation, this gives us an opportunity to determine ethnicity, urban/rural residence, and sector of the economy (agriculture, trade, industry, or civil service) for each of these social groups, showing also the major corresponding labour relations. We should remember, however, that the revizia focused on the formal obligations of social groups, and can therefore sometimes obscure actual labour relations. For instance, if a certain commune hired workers to perform those duties for them (such cases, although not very common, can be found in the historiography),Footnote 9 this will not be visible from this type of source. Moreover, these materials have a tendency to underestimate the size of migration and the level of urbanization, generally tending to record the migrants (both seasonal and permanent) in the places they originally lived. The other problem is the project framework required to consider the different gender and age groups. Women were recorded and the age of each person was indicated in the revizskie skazki, the primary documents of the revizia; unfortunately, these data were never aggregated as they were of no interest to the tax authorities. So, we had to use a range of samples to estimate the size of the female population and of the different age groups.Footnote 10

To study the dynamics of the process, we also consider material from earlier revizias – those of 1719–1724, 1744, and 1763.Footnote 11 Unfortunately, direct comparisons between them are hindered because of the reforms of 1775, which significantly changed the territorial-administrative divisions, making the new districts and provinces incomparable with earlier ones. As a result, changes can be tracked only for social groups as a whole.

LABOUR RELATIONS IN RUSSIA IN 1795: A GENERAL OVERVIEW AND THE ROLE OF TRIBUTARY LABOURFootnote 12

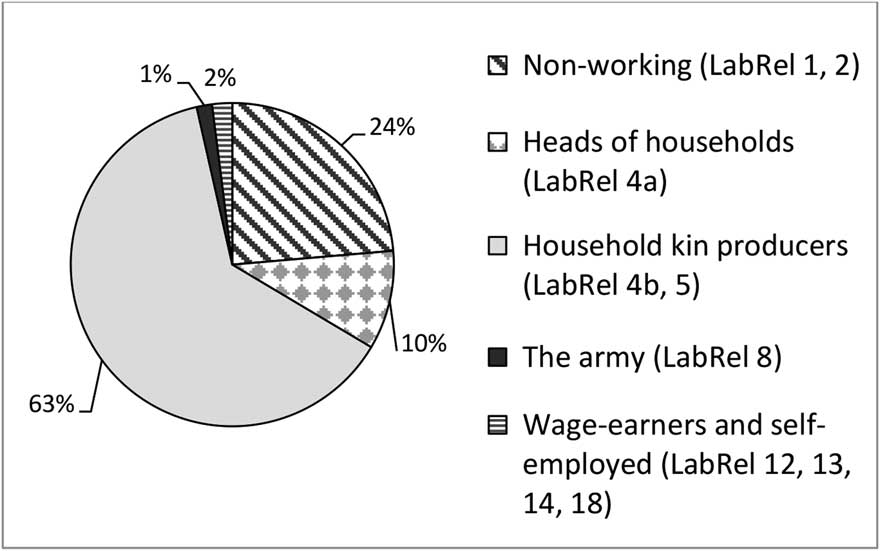

First, it is necessary to outline the general structure of labour relations in imperial Russia. It was a predominantly agrarian society; for over ninety-six per cent of the total population primary labour relations were connected to their households (as heads of families, working family members, seniors, and children, LabRel 1, 4a, 4b, and 5). All other relations, including tributary, were secondary. Only small groups of the urban population, mainly merchants and skilled artisans, but also the nobility providing military service and civil administrators, can be identified as self-employed or wage earning; this category did not exceed two per cent of the total population, and, together with the other two per cent (regular army soldiers), they make up the remaining four per cent of the population. The actual proportion of free wage labour was generally higher than our sources suggest, but it certainly did not involve large masses of the population.Footnote 13

Figure 1 Primary labour relations, 1795.

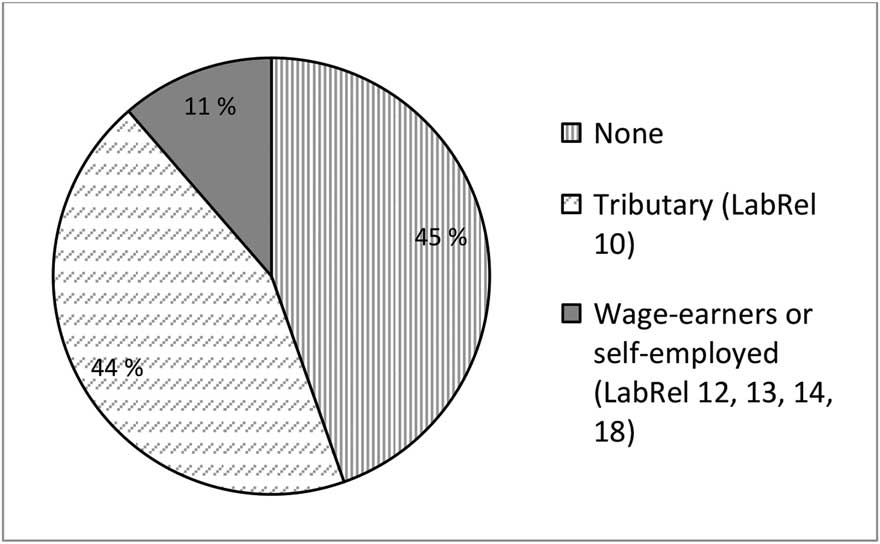

The picture of secondary labour relations of the two main economically active groups (heads of households and household kin producers) presented in Figure 2 is significantly more diverse, however, as large numbers of peasant households were involved in labour migration (otkhodnichestvo), waged work, or self-employed work in rural industry (promysly), or performed certain labour obligations that can be classified as tributary.

Figure 2 Secondary labour relations of heads of households and household kin producers.

As can be seen, forty-four per cent of the economically active population were involved in various forms of tributary labour (LabRel 10). The absolute majority (eighty-eight per cent) of them were serfs, working in the corvée fields of their landlords.

The long discussion in both Russian and Western historiography of the factors in the development of this institution and its similarity with serfdom in Central and Eastern Europe led specialists to suggest that the creation of the manorial jurisdiction of landlords in 1592–1593 was the government’s response to an economic crisis, an attempt to stop the massive relocation of peasants and to provide the lesser nobility with working hands.Footnote 14 Russian historiography, generally, concentrated on the issue of whether the prohibition on peasants leaving the estates of their masters, about 1592, was enforced by a government decree, which has never been found however, or whether it was the result of purely economic factors. Although the majority of specialists now agree that the 1592 decree did in fact exist,Footnote 15 modern works nevertheless tend to see the development of the manorial economy of the nobility (with the nobility settling in their newly acquired villages between the late fifteenth and early seventeenth centuries) as a major driver in the development, if not the emergence, of serfdom; much later, from the second half of the eighteenth century, we can also track the significant impact of the market economy and growing agricultural exports, which encouraged landlords to develop the corvée and increase the labour obligations of dependent peasants, generally in the sense suggested by Engels and Kula.Footnote 16 Initially, however, in the country’s central regions market institutions had no significant impact on those relations.

In recent years, several studies have appeared examining the various labour duties performed by the groups of population considered “tax paying” (tyaglye). Merchants and craftsmen in the cities were obliged to serve in the customs service and to organize the production and sale of goods over which the state had a monopoly;Footnote 17 peasants were responsible for keeping the roads in their neighbourhoods in an acceptable condition,Footnote 18 helped in the reconstruction of fortifications, and provided housing for troops (postoi)Footnote 19 and carts for government transport (podvody). The latter obligation was divided between the peasants and a large group of professional coachmen, yamshiks, who dated back to the early Muscovy period and whose status and services would require a quite separate study. The problem for scholars is that those services were imposed by local authorities, which makes them extremely hard to study owing to the lack of extant archival material and the absence of aggregated data. For now, the picture we have is too fragmented to allow any generalizations to be made.

In this article, we will not consider these issues further and instead focus on those groups who, according to data from the fifth revizia, performed labour duties for the polity as their major obligation.

“Services” (sluzhba) and “duties” (povinnosti) of different estates, performed in kind, were very widespread in MuscovyFootnote 20 and probably had their origins in the earliest stages of the development of mediaeval Russian society.Footnote 21 In Russia, with its open borders, severe climate, and long distances, the demand for large amounts of labour, especially for military and transport purposes, emerged much earlier than the state’s ability to pay to meet that demand.Footnote 22 Normally, this work was remunerated in the form of land rather than money; even more generally, landowning, for all the estates, was linked directly not only to paying taxes (tyaglo) but also to performing certain work (although the ratio of monetary to labour obligations varied).Footnote 23 Theoretically, these services were imposed “on land”, not on people, and those who abandoned the land were no longer obliged to perform “service”.Footnote 24 А century-long discussion in Russian historiography has revealed the overall similarity of those relations to the land-based commendation in mediaeval Europe, but also revealed significant differences, especially the direct and overall nature of service to the state and the more active role of communes, both peasant and urban, in its performance.Footnote 25 As the empire treated its subjects in accordance with their major obligations, the imposition of such obligations led to the formation of specific social groups, with the specifics of their status more or less documented.

The burden of direct labour obligations was significantly relieved by the role of the communes, which were especially strong and influential in Russian society. The communes had their own institutions, were collectively responsible for obligations to the state, and had the right to redistribute this burden among its members. New studies have revealed that the communes were not always silent and content with the administration.Footnote 26 Tax increases especially could result in a reluctance to pay, which, given the lack of means of coercion available to the administration, often resulted in the accumulation of debt. Surprisingly, the peasants were often less reluctant to accept demands to perform certain duties in kind and even serve in the imperial army, which took the men away from their homes for twenty-five years. These issues require more detailed studies, but it is fairly clear that the commune members performed such tasks on a rotation basis, and also used the recruitment system to relieve communities of undesired members.Footnote 27 Generally, the direct claim on tributary labour forced the commune to collaborate with the administration, while the attempt to use market mechanisms (i.e. raising payments due in order to force peasant households to release labour) led to discontent, which usually took the form of collective petitions in which the commune members insisted that they were unable to pay the increased sum. The other reason is that, because of the high volatility of both labour and grain markets, the direct labour obligations were more predictable for a commune and a household (in terms of the amount of work to be done) than the efforts needed to collect money for monetary payments. This was especially true in years of natural disaster, when the massive supply of labour outstripped the need for workers, and, surprisingly, in years of bumper harvests, when the supply of grain exceeded demand.Footnote 28

For the groups we are discussing, their tributary labour obligations lay either in the military sphere or in industry. These workers numbered about 1,700,000. Based on previous studies, we have estimated the size of the free wage market to have been 3,200,000, and the size of social groups not involved directly in agriculture at around 779,000, according to the database, so we can conclude that about twenty-six per cent of workers in the non-agricultural sphere were mobilized using tributary labour relations. The numerous social groups present in the sources can be combined into two larger clusters according to the nature of their labour obligations.

First, we have the “service class” groups, who performed military service for the state and whose status was determined by that fact. They included the Cossacks of Don, Yaik, the North Caucasus, Volga region, and Siberia, whose communities were formed in the steppes belt in the course of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, largely from fugitives from the central serfdom area, and later integrated by the tsar; and the Bashkirs and the Kalmyks, large indigenous nomadic and semi-nomadic groups. Two other groups considered here are the odnodvortsy of Central Black Earth Region, the descendants of the lesser nobility of the former frontier, with no (or very few) serfs and a transitional status between that of the nobility and the peasantry, and the Ukrainian Cossacks of Hetmanate (Left-Bank) and Slobodskaya Ukraine. By 1795, their service had been replaced by monetary payments, but it was still performed in the course of eighteenth century.

Secondly, we have groups of peasants bound to different industries (pripisnye) and shipbuilders (lashmans). Although the binding of certain peasant communes to industries was a sporadic phenomenon in the seventeenth century, this group was generally constituted during and after the reforms of Peter I, in particular with the rapid growth of the Urals metals industry.

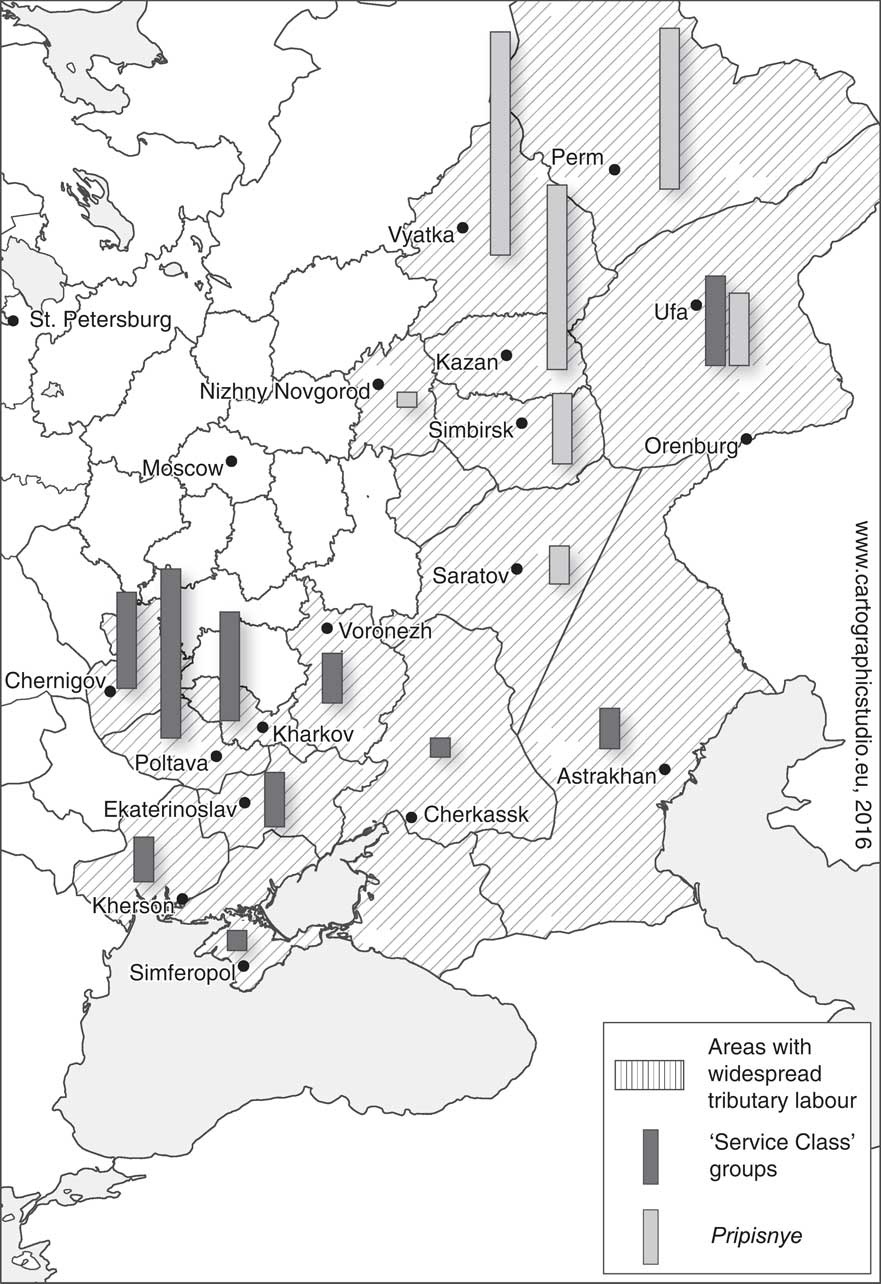

The territorial distribution of these two groups is illustrated in Figure 3. Small groups of service class and pripisnye were scattered throughout the country, including its central provinces, but it was only in the wide belt of the southern and eastern frontier regions that they formed a group exceeding three per cent of the total population. The service class was localized mainly in the steppes and forest steppes of Left-Bank Ukraine, the Black Sea, and Lower Volga regions, as well as in the Southern Urals, where the Bashkirs formed another large group in this stratum. The pripisnye were generally located to the north-east of them, in the forest areas of Middle Volga and the Central Urals.

Figure 3 Territorial distribution of “service class” and pripisnye, 1795.

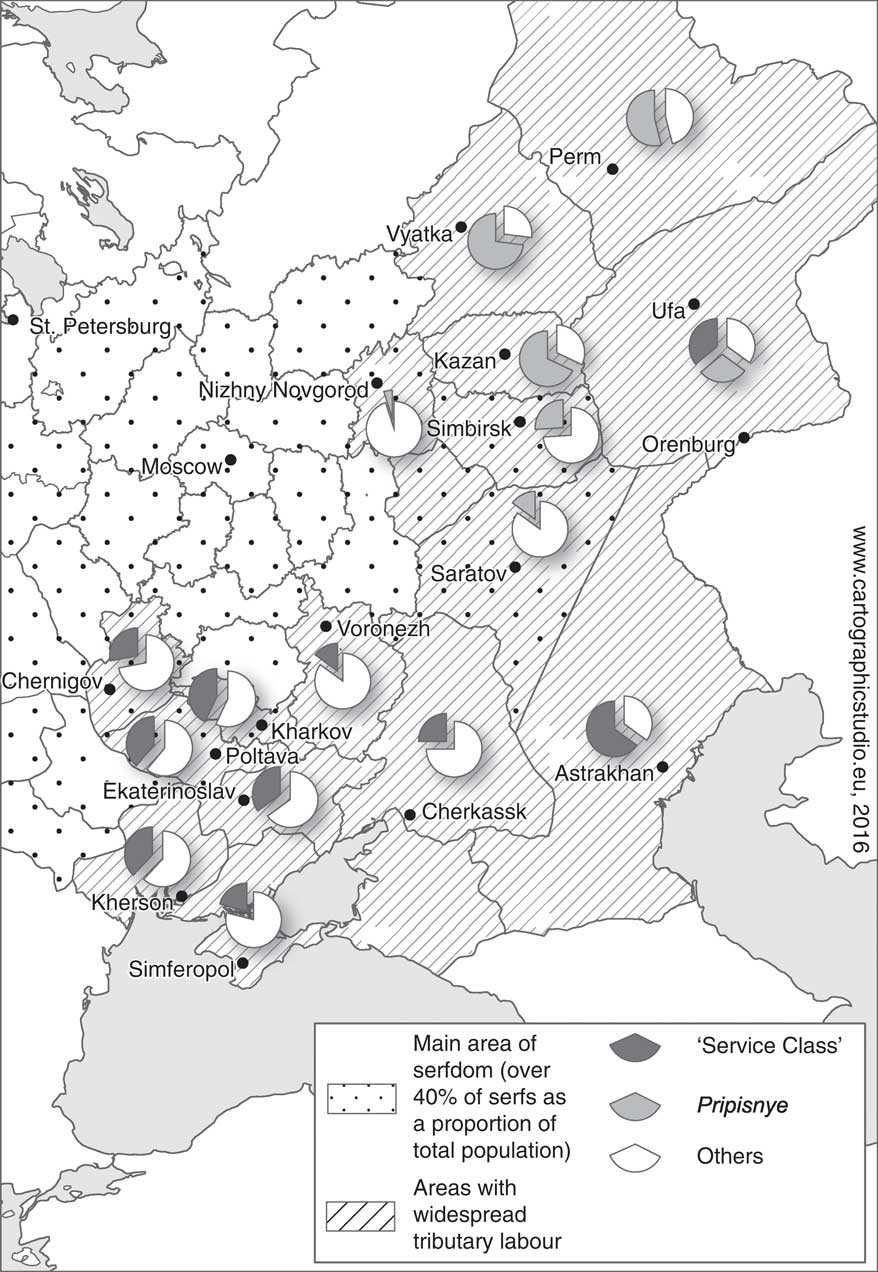

This wide “belt of tributary labour” flanked the country’s central regions from the south and the east. The ratio of the groups bound to obligatory work and services significantly varied however (Figure 4).

Figure 4 “Service class” and pripisnye as a proportion of total population, 1795.

As can be seen, those groups formed the majority of the population in the forest areas of Middle Volga and the Southern Urals, as well as in the frontier, poorly populated semi-desert province of Astrakhan. In the developed agricultural regions of Left-Bank Ukraine and the Black Sea, as well as in the central provinces of the Volga region, they varied from one-quarter to one-half of the total population, decreasing to just a few per cent in the densely populated Nizhny Novgorod, Simbirsk, Saratov, and Voronezh regions, where the area of significant tributary labour coincided with the main area of serfdom, linked to the country’s inner regions.

“SERVICE CLASS”

We now review the history of those groups, starting with those whose work for the state was considered to be “service” – a mark of semi-privileged status. We should note, however, that the legislation and the state in general never treated those groups as a single estate, preferring to deal with each of them separately, although sometimes the documents generalize them as “the military citizens”, or “service class”.Footnote 29 Running their own households (or, in the case of nomads, sustaining their traditional way of life), they were not taxed but instead obliged to perform military service or work for military institutions. The Russian empire had an open southern border of more than 2,500 kilometres in the European part of the country, and this significant military force, although ineffective against the regular armies of the European powers, remained essential there.Footnote 30

The composition of these strata is very mosaic. The revizia outlines about forty different groups, each with a specific legal and social status. Four major circles can be distinguished among them however – Ukrainian Cossacks (cherkasy, according to the revizia terminology), the Cossacks of Don, Bashkirs, and Kalmyks. Close to them are the odnodvortsy, descendants of poor nobles in the former frontier provinces of Central Black Earth Region, who had lost their noble privileges and whose landowning and service obligations had become communal (unlike nobles, who owned land and served personally) by the late seventeenth century, alongside a large number of small groups that originally served along the fortified lines (“ploughing soldiers”, “fortification guards”, etc.).

With the significant trend towards regional studies in Russian historiography, a large number of monographs have appeared in recent decades discussing these groups from the point of view of changes in their status and obligations. Several attempts were also made to generalize those results, focusing on the issues of the status of ethnic minoritiesFootnote 31 or on migration and the economic development of new regions.Footnote 32 We will try, here, to focus on the long-term shifts in labour obligations that took place.

The origin of those groups was different: the Don Cossacks owe their origins to the migration of the Russian population to the area of the Lower Don, which at that time was not controlled by the government; the Ukrainian Cossacks emerged as an organization of armed people on the south-east frontiers of the Polish state, which was seized by Russia in the second half of the seventeenth century; the Bashkirs were the autochthonous population of the southern Urals region, with a semi-nomadic way of life; and the Kalmyks, classic nomads, migrated to the Lower Volga from Dzungaria in the first half of the seventeenth century. The fortified lines in the Central Black Earth Region, zaseki, constructed in a major flurry of activity in the mid-seventeenth century, were a place of service for diverse and numerous groups of military, and some of them retained their specific status even after being abandoned when the military moved south in the final decades of that century.

The majority of those groups, excluding the Black Earth Region service class, had certain elements of political autonomy in the seventeenth century, but, in general, that autonomy was ended or severely curtailed during the reign of Peter I. The autonomy of Hetmanate in Left-Bank Ukraine, granted to the Cossacks in 1654, was largely abandoned after the first hetman, Ivan Mazepa, defected to the Swedes in 1708. The elective institutions of the Don Cossacks were put under direct control after Bulavin’s rebellion in 1708. Ayuka Khan’s death in 1723 triggered a long-drawn-out power struggle between the different groups of Kalmyks, which resulted in the Russian administration assuming greater control.Footnote 33

At the same time, the nature of their service had to change. In the seventeenth century, the armed communities pledged to protect the borders of the state, as well as to perform various tasks for the government, such as escorting ambassadors to neighbouring states, and preventing attacks from within their territory on the inner regions of the country. In response, they were recognized as “service class”, which guaranteed their self-rule and landowning, gave them a number of economic privileges (such as the exemption from duties on distillation awarded to the Ukrainian Cossacks and the exemption from the payment of duties on salt production granted to the Bashkirs), and the right to receive a regular zhalovanie, the wage for service. An important part of the agreement was the right to directly appeal to the monarch; the history of the steady stream of embassies sent by the Cossacks and Bashkirs to the tsars continued throughout the seventeenth century,Footnote 34 and during the same period the Hetmans and Kalmyk Khans ran a largely independent policy. These were guaranteed by a series of charters, the initial terms of which were revised from time to time in light of changed circumstances however.

Russia’s foreign policy successes and changes in the military sphere led to these areas gradually becoming the inner regions of the country. The Turkish fortress at Azov, at the mouth of the Don, was seized by Peter the Great in 1696, marking the start of a permanent Russian garrison there (though Azov was returned to Turkish rule in 1711–1739). With the construction of Orenburg and the line of forts on the Yaik, in 1739 the Bashkirs also found themselves within the empire’s expanding borders. Due to tensions in relations with Poland and Turkey, the number of Russian troops in Ukraine also gradually increased during the eighteenth century. The Kalmyks, who occupied the steppes on both sides of the Lower Volga, were less affected, but in 1771 most of them migrated back to Dzungaria, and the rest chose to stay on the right bank of the Volga and were surrounded by territories under direct Russian control.Footnote 35 This led to significant changes in the character of military service.

Firstly, the state began to require participation in long-distance military expeditions and large campaigns. In 1695–1696, the Don Cossacks played a significant role in Peter I’s campaign against Turkey, acting largely separately.Footnote 36 By the time of the 1735–1739 campaign they had become an irregular part of the army, acting under the command of regular officers. The Bashkirs and the Kalmyks took part in the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763), also as part of the Russian army. In the second half of the century, this practice became common, and the presence of Cossacks and irregular steppes cavalry became one of the most characteristic features of the Russian army.

Systematic service on the borders was even more important. The Don Cossacks had regularly been sent to endangered parts of the steppe borders since the 1720s. Moreover, the government periodically moved certain groups of Cossacks to form new regiments where they were needed. In 1730, 600 Cossack families were sent to settle at the Tsaritsyn line, and in 1792–1793 three Don regiments were relocated to the North Caucasus. The Bashkirs had largely been responsible for servicing the system of fortified lines in Yaik since the late 1730s. In the same decade, the irregular services of Ukrainian Cossacks and the Black-Earth Region service class were significantly reshaped with the formation of a corps of border guards, the so-called Land Militia, which was also commanded by regular officers.

Because it involved removing men from their families for long periods and required expensive equipment and supplies, such service became a heavy burden for the ordinary members of the commune. At the same time, there began a period of rapid migration to these regions, as they were no longer frontier regions and dangerous. The formation of large non-serving (mainly peasant) groups in those lands led to the growing involvement of the imperial administration in local affairs, as large numbers of “regular citizens” appeared in the region and, behind them, the centralized state.Footnote 37

Attempting to distinguish between the privileged and non-privileged population, the government tried to compile registers of service class, and encountered much difficulty in doing so. Attempts to hold a census among the Bashkirs had little success until the 1750s,Footnote 38 when the first reliable Don census was conducted in 1756,Footnote 39 and estimates of the nomadic Kalmyk population remained quite approximate until 1771, when the majority of them migrated to China.Footnote 40

At the same time, the local elite were extremely keen to be ennobled.Footnote 41 The landowning of the “service class” communities was corporative, and they benefited most from the communal redistribution of land; the problem was that even the large landholders continued to depend on the commune. Achieving the status of a noble (either by being promoted to the rank of an officer in military service or by proving the noble origins of one’s family) opened the way to privatizing those plots of land, although this was always met with resistance on the part of the commune. The result of this internal conflict depended on the strength of communal traditions of land ownership and on the position of the government, as turning these lands into noble estates inevitably led to the decline of military service. In eighteenth-century Ukraine, much of the land was privatized by the Cossack elite, which very early on had marked its claim to noble status and finally obtained it in the 1780s, in response to its consent to the abolition of the autonomy of the Cossack administration. As a large amount of land was taken out of the hands of Cossack communities, they went into decline and it became difficult for them to bear service. By 1795, the position of Ukraine’s remaining service class was rapidly changing towards that of state peasants, as their military service was becoming more and more incidental, being replaced by tax payments. Contrarily, similar tendencies among the Don elite were suppressed by the government, interested in the vast military power that the Voisko supplied for the wars against Turkey and Iran.Footnote 42

The growth of the non-service population implied the increasing presence of the imperial administration, searching for fugitive serfs, regulating conflicts between the service community and newcomers, and attempting to influence traditional authorities. It led to numerous conflicts throughout the eighteenth century: in Ukraine, Hetman Mazepa defected to the Swedes in 1709; the Don Cossacks rebelled in 1708 and again in 1793–1794, the Bashkirs in 1737–1739, 1755, and 1772–1774. After such events, the government usually significantly curtailed the autonomy of the local elective institutions responsible for local affairs and the organization of military service, but economic privileges remained untouched and were reconfirmed.

Summarizing the above, during the eighteenth century the evolution of those groups, although very different in terms of origin, ethnicity, and in how they were integrated into Russian society, generally followed the same path. Their military service shifted from the defence of their own territory, with minimum intervention from the civil or military administration in their affairs, to a kind of universal (for those groups) conscription, under the direct control of the military administration. There is no reason to think that this institution gradually declined in the eighteenth century; on the contrary, the number of “military citizens” grew, and new groups (like the Cossacks along the newly constructed fortified lines) emerged. Moreover, none of those groups actually disappeared in the eighteenth century. Even those that, due to the shifting of the frontier, had found themselves in the inner regions of the country and stopped performing actual military service by the mid-eighteenth century (like the odnodvortsy, who had to make payments instead of service) continued to exist, continuing their semi-militarized way of life and not dissolving within the larger social strata.

What factors contributed to their stability? On the one hand, all those groups had a privileged status, officially confirmed, and owned land; they were organized into communes and had means, both legal and armed, to defend their rights. Although the understanding of some privileges, the size of their land, and the role of their elective institutions in local affairs could be disputed and periodically even caused conflicts, the government generally honoured its agreements with them. On the other hand, the government itself was interested in their service. Numerous, having experience of service at the frontier and cultivating their military traditions, they provided the Russian army with a significant supply of well-trained and dedicated irregular cavalry, which had played a significant role in military campaigns not only in the steppes but also in the European theatre of warfare.

The real threat to the specific status of these communes came from inside, not outside. The tendency of local elites to privatize the land and to obtain noble status can be traced in all of them. The existence of communal institutions, as well as the government’s demand for military service, were obstacles to this privatization, and where the process of the nobilitation of local elites developed rapidly the decline of local communes was inevitable. Even the groups that had completely terminated their military service (lashmans, Hetmanate, and Slobodskaya Ukraine Cossacks, odnodvortsy) did not completely lose their status before the end of the eighteenth century. One characteristic of enlightened absolutism was its reluctance to accept forced changes in the status of different social groups.Footnote 43

PRIPISNYE

The next group to be addressed are the numerous workers in industry and transport. As is well known, at that time, even a comparatively small manufacturer required a large number of workers to produce and deliver the raw materials. In metallurgy, ironstone had to be mined and charcoal produced; in the potash industry, oak logs and ash had to be prepared; in shipbuilding, trees had to be felled and timber dried.

Unlike those groups associated with military service, the emergence of most of the groups associated with industry and infrastructure dated to the imperial period, especially the time of Peter I. The creation of Peter’s new army and navy, and the onset of military and economic rivalries with European powers, demanded the creation of a fairly extensive military industry (especially metallurgy and the production of potash, a necessary component of gunpowder and shipbuilding). It required a very large amount of unskilled labour. The situation was complicated by the fact that both the theatres of war and the most valuable resources were located on the periphery of the state, in the thinly populated regions. At the time, the best ore mines were located in the Urals; the large hardwood forests were also mainly located outside the interior of the country, especially in the Middle Volga region. The government solved this problem by imposing tributary obligations on the local population. The two largest groups in the database are “those assigned to the Admiralty” and “those bonded to the steel and potash plants”.

Despite the similarity of their status and obligations, the origin of these groups was very different. The group of lashmans was formed based on the indigenous service class groups of the Volga region, mostly Tatars. By the early eighteenth century this region had become part of the country’s interior, and there was less need for them to contribute military service; in a 1718 decree,Footnote 44 Peter I ordered military service to be replaced by work in the Admiralty in Kazan, and called the newly organized group “the lashmans” (from the Low German laschen, to cut logs).Footnote 45 Having lost their service status, the lashmans preserved some of their traditional privileges, including their militarized social organization, with elected decani and centurions, and the right to bear arms.Footnote 46 They were not recruited, and their communes enjoyed an autonomy generally more extensive than that of the region’s tax-paying population. The size of this group changed over time, but the main core, located in the Middle Volga region, remained stable over time. The size of the Tatar “service class”, which soon became a group of lashmans, was 63,000 in 1719, growing to 69,000 in 1744 and 76,000 in 1763.

The need for labour for the newly established Urals metallurgy and Volga region potash industry was even greater. Peter I found the solution in his manifest of 1724, the so-called Plakat.Footnote 47 Under this law, certain peasant communes (state peasants, as a rule) could be “bound” to a nearby factory for the purpose of paying taxes, without the right to be paid in monetary form. This arrangement went by the name of pripisnye. The daily wage for this work was set by law at a rate much lower than the free wage in those regions, where the supply of wage labour was quite low.Footnote 48 This practice, invented in the Urals metallurgy industry, was expanded later to other regions and branches of industry, such as potash production in the Middle Volga.Footnote 49

The size and territorial presence of this group expanded in the course of the first half of the eighteenth century, following the expansion of metallurgy in the region,Footnote 50 with the new peasant communes being bound to the numerous newly constructed factories. In 1719, only 97,000 men were recorded in this group, increasing to 161,000 in 1744 and 184,000 in 1763; soon after, following a series of revolts, the government officially stopped the practice of binding peasants to the factories, but those already bound remained so.

If a factory were privatized, which often happened, especially in the 1740s, when the influential aristocracy discovered that factories could be highly profitable, this did not end the peasants’ obligations. Instead, the new owner assumed the obligation to pay to the treasury the poll tax, which was then worked off by the pripisnye. This practice increased over time – whereas in 1719 only a few per cent had been bound to privately owned factories, this had increased to over one-third by 1763.Footnote 51 Even the large landowners used it, because it was much harder to relocate their serfs from the interior of the country than to use local peasants as pripisnye; and it was especially important for the non-noble manufacturers, who could not own serfs (Peter I’s decree of 1721 allowed it, but the serfs, posessionnye, were considered the property of the factory, not of the owner). The posessionnye were much less widespread than the pripisnye however. For the mid-eighteenth century, we know even of cases in which state peasants (those who lived in the tsar’s lands and were statutorily defined as “free rural citizens”) were bound to private factories.

Still, from a legal point of view, pripisnye were not turned into serfs. The state administration periodically tried to establish its control over the use of their labour, and in 1762–1763, after a series of rebellions, a major government commission led by Prince A.A. Vyazemsky, one of Catherine II’s most trusted advisers, established a system of norms concerning relations between the factory owners and the communes of the pripisnye. Due to Orlov’s extensive study,Footnote 52 we know that the major complaints of the pripisnye were linked to “misattitudes” on the part of the administration, including wrongly calculating the number of days worked, reluctance to include days spent on the road to the factory as days worked, and, especially, the attempts of the administration to intervene in the communal redistribution of duties. The peasants insisted that the use of communal institutions permitted them to perform their duties with the minimum of damage to their own households (the administration said, probably not without reason, that they tended not to send the best workers and the best horses to the factory, especially during the agricultural season).

A small but very important group of industrial workers were skilled masters and apprentices. Initially, this group was formed as free wage, but in 1735, after a series of petitions from factory owners, they were bound to the factories as vechnootdannye. The owners insisted that there was an urgent need to keep these people at the factories and to avoid situations in which their original communes exercised their right to have them returned or to send them to the army as recruits. They asked that those workers not be allowed to be freed, but to have them bound to the factories, however, following the general idea that the social status of a social group must be determined according to its major obligations.Footnote 53

So, the newly established industry required large amounts of labour, and the administration solved the problem by both changing the nature of the service to be performed by the “service class” groups and by “uncommodifying” the obligations of groups of taxpayers. It is interesting that, in itself, this solution did not become a source of discontent.Footnote 54 While the government’s attempts to commodify the obligations of “military citizens” often became the reason for their rebellion, the reverse was not regarded as unacceptable.

CONCLUSIONS

The system of state-organized and state-controlled tributary labour, which existed in Russia in the eighteenth century, appeared in response to the needs of the state, which was developing large industries and building systems of border protection in desolate and under-populated regions. The population there made a livelihood through agriculture, trade, and other traditional activities, and it was unlikely that the state would be able to make them significantly change their traditional way of life through economic measures (whether by offering sufficiently attractive wages or by imposing a sufficiently heavy tax burden).

At the same time, in a society where the majority of the population was, in different ways, bound to the soil, and therefore had very limited mobility, it was very unlikely to attract enough labour migrants to these territories; also, the supply of large groups of highly specialized workers or military personnel would inevitably become a problem, given the weak development of markets and transport. In these circumstances, the polity had no option other than to impose direct military and labour obligations on the local peasant communes. The direct nature of these obligations made them more predictable than monetary ones, and performing them on a rotational basis allowed the communes to also preserve their traditional way of life; this act on the part of the government usually did not therefore lead to open discontent.

The development of a system of obligatory work was facilitated by the fact that the idea of the necessity of performing different types of work in addition to, or instead of, paying taxes was very natural for Russian society. Direct “service” for the polity (especially military service) was considered honourable and linked to a range of privileges.

Such privileges could include different specific social and economic rights (such as the exemption from duties on the production of salt granted to the Bashkirs), but the basic and most important of them was a strong guarantee of the semi-privileged status of landowning. Unlike state peasants, the “service-class” groups could not be turned into serfs by an act of “donation” on the part of the emperor; even the pripisnye, bound to the private factories, could appeal to the royal administration if their obligations were unlawfully increased by the factory owner. For the local elites, administering these works and services strengthened their position within the communes, and performing military service allowed them to achieve the rank of officer and, in certain circumstances, become a member of the nobility.

The system of tributary labour obligations in place in eighteenth-century Russia emerges as an arrangement better suited than monetary and market mechanisms of mobilizing and allocating labour and other resources to meeting the interests of both the state (which needed a large amount of labour to protect its borders and develop new industries) and of those groups on which these obligations were imposed. This was partly a matter of geography, with tributary labour relations being most widespread in thinly populated border regions, and of a certain, historically determined, predilection for such types of arrangements.