No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

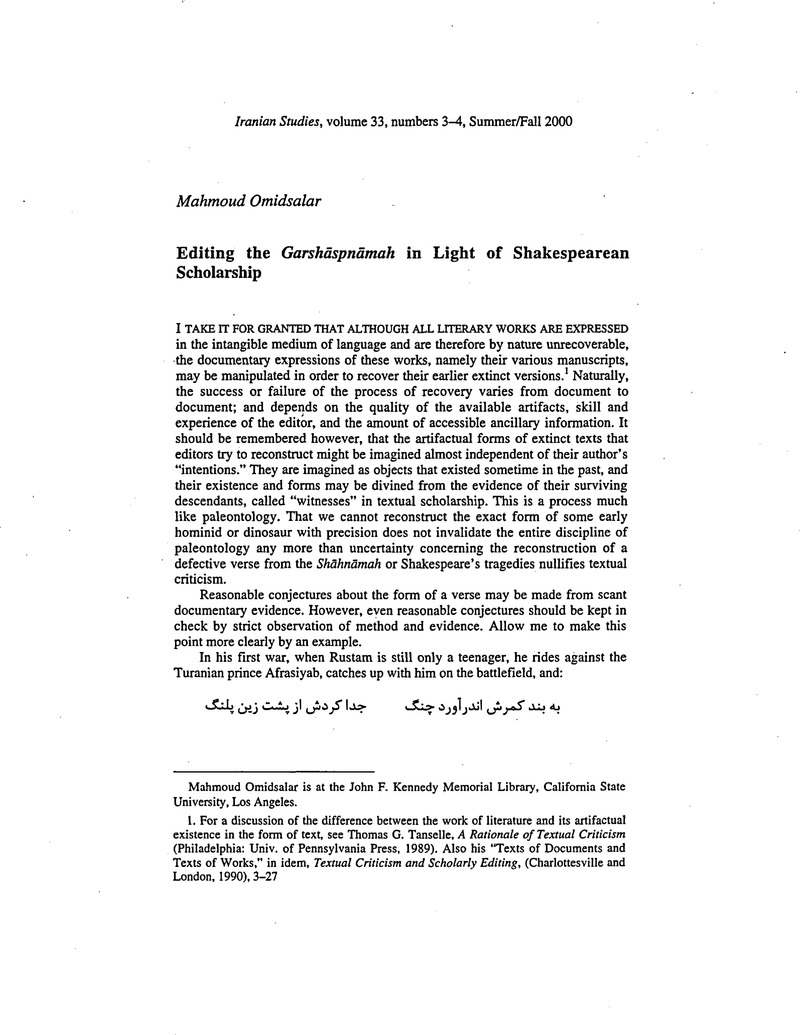

Editing the Garshāspnāmah in Light of Shakespearean Scholarship

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 January 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Resources

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Association For Iranian Studies, Inc 2000

References

1. For a discussion of the difference between the work of literature and its artifactual existence in the form of text, see Tanselle, Thomas G., A Rationale of Textual Criticism (Philadelphia: Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, 1989)Google Scholar. Also his “Texts of Documents and Texts of Works,” in idem, Textual Criticism and Scholarly Editing, (Charlottesville and London, 1990), 3–27Google Scholar

2. All quotations from the Shāhnāmah are from the Khaleghi-Motlagh edition.

3. The manuscripts to which I refer are those that have been used for Khaleghi-Motlagh's edition of the Shāhnāmah. These are: the Florence manuscript (Ms. CI.III.24 [G.F.3]), dated 614/1217; the London MS (Add, 21. 103) dated 675/1276; the first Istanbul codex from the Topkapi Sarayi (H. 1479), dated 731/1330; the first Leningrad manuscript (no. 317-316), dated 733/1333; the first Cairo manuscript (S. 6006), dated 741/1341; the second Cairo codex (tārīkh-i fārsī, 73), dated 796/1394; the Leiden manuscript (Or. 494), dated 840/1437; the manuscript of the National Library in Paris (Suppl. Pers. 493), dated 844/1441; the codex of the Vatican Library (Ms. Pers. 118), dated 848/1444; the Oxford manuscript (Ms. Pers. C.4.), dated 852/1448; the second London manuscript (Add.18,188), dated 891/1486; the third London codex (Or. 1403), dated 841/1437; the second Leningrad manuscript (s. 1654), dated 849/1445; and the second Istanbul codex (H. 1510), dated 903/1498.

4. For a description of the manuscripts used by this edition see the introductory tables of the edition.

5. Zajaczkowski, Ananiasz, Le traité Iranien de l'art militaire Ādāb al-Ḥarb wa-sh-Shajāᶜa. introduction et édition en facsimilé (Ms. British Museum, Londres) (Warszawa, 1969), 24Google Scholar.

6. Ādāb al-ḥarb, f. 75 verso.

7. I have no doubt that the form ![]() is in fact what Firdawsi wrote. However, my personal opinion is no more than an educated speculation, and remains so until at least one Shāhnāmah manuscript, the text of which supports this reading, is discovered. Such an opinion belongs neither in the body of the text nor in the critical apparatus. It should however, be expressed in the notes to the text.

is in fact what Firdawsi wrote. However, my personal opinion is no more than an educated speculation, and remains so until at least one Shāhnāmah manuscript, the text of which supports this reading, is discovered. Such an opinion belongs neither in the body of the text nor in the critical apparatus. It should however, be expressed in the notes to the text.

8. Khaleghi-Motlagh has already discussed “the promise and pitfalls of using ancillary materials in editing the Shāhnāmah” in an article entitled “Ahamiyyat va khaṭar-i ma˒khiẕ-i janbī dar tasḥīḥ-i Shāhnāmah,” in Īrānshināsī 7 (1996): 728–52Google Scholar.

9. Naturally, the other possibility that the ![]() khalang >

khalang > ![]() khadang/

khadang/ ![]() palang corruption may have already existed in Firdawsi's source—unlikely as it is in my opinion—may not be discounted.

palang corruption may have already existed in Firdawsi's source—unlikely as it is in my opinion—may not be discounted.

10. Sisson, C. S., New Readings in Shakespeare, 2 volumes (Cambridge, 1956)Google Scholar.

11. Sisson, 1:8.

12. He writes, “In the course of training in bibliography, palaeography, and archives, a student was reading aloud from an Elizabethan document thrown upon the screen by an eidiascope. He fell into error at one place, reading to see for used. A small bell rang in my memory, and proceedings were suspended for the consultation of a text of Shakespeare. The Quarto text of A Midsummer Night's Dream 5.1.208 reads, “Now is the Moon vsed.” It became at least plausible that the compositor of the Quarto had made the reverse error, reading vsed for to see, in the easy confusion of an initial Secretary v with to, followed by the even easier confusion of d with e.”

13. Sisson, 2: facing pages 157 and 270.

14. Bowers, F., “The New Textual Criticism of Shakespeare,” in idem. Textual and Literary Criticism (Cambridge, 1966), 66–177Google Scholar.

15. Ibid., 71.

16. Ibid., 72.

17. Ibid., 74.

18. Ibid.

19. Also see Shaaber's, M. A. review of Sisson's book in Shakespeare Quarterly 8 (1957): 104–107CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

20. For a detailed study of his life and art see Khaleghi-Motlagh, J., “Asadī-yi Ṭūṣī,” Revue de la Faculté des lettres et sciences humaines de l'Université Ferdowsi, 13 (1978): 643–79Google Scholar; 14 (1978): 68-131.

21. A complete facsimile edition of this text, (codex vindobonensi A. F. 340 of the Austrian National Library, Vienna) has already been published. See Seligmann, R. R., Codex Vindobonesis sive Medici Abu Mansur Muwaffk Ibn Ali Heratensis Liber fundamentorum pharmacologiae pars 1 (Wien, 1859Google Scholar; reprinted Graz, 1972). In 1344/1965, M. Minovi produced a facsimile publication of part of the text in Tehran.

22. For a brief discussion of the manuscripts and editions of the GN, see J. Khaleghi-Motlagh's paper “Gardishī dar Garshāspnāmah,” in Iran Nameh 1 (1362): 395–96Google Scholar, and H. Yaghma˒i's introduction to Garshāspnāmah, ed. H. Yaghma˒i (Tehran, 1354/1976)Google Scholar.

23. Yaghma˒i, who used this fragment in his edition, thought that it might date from the fifth century Hijri (eleventh century A.D.) Nothing in the fragment's orthography indicates that it could be that old. Be that as it may, its almost total lack of diacritical marks significantly decreases its authority even compared to some younger manuscripts. I am fairly convinced that given its paucity of diacritical marks, it must have been a private copy made by the owner for his personal use rather than one that was made by a professional copyist.

24. I have already pointed out some of this codex's superior readings. See Omidsalar, M., “Some Notes on the Text of the Garshāsp-nāma,” in Golestān: Quarterly of The Council for the Promotion of the Persian Language and Literature in North America, 1 (1997): 51–71Google Scholar.

25. Several folios of this manuscript are in the handwriting of a later scribe, who consciously but unsuccessfully imitates Asadi's writing style. That however, is of no significance because the amount of text in Asadi's own handwriting is over 200 folios, and thus more than adequate for our purposes.