A remonstrance of divers remarkeable passages concerning the church and kingdome of Ireland is a well-known contemporary account of the uprising that began in Ulster on 22 October 1641, before rapidly descending into a barbarity and cruelty with which it was soon met by the settler regime in depressing kind.Footnote 1 Towards the end of December 1641, after the rebellion had spread to many other parts of the kingdom, eight Church of Ireland clerics were commissioned by the lords justices, Sir William Parsons and Sir John Borlace, to gather sworn testimony from the rebellion's victims. The commissioners’ work started on 30 December 1641 and proceeded rapidly. More than 400 depositions had been sworn already when, on 11 February 1642, the Irish council wrote to the lord lieutenant of Ireland, Robert Sidney, second earl of Leicester, informing him of the commissioners’ activities, and explaining that examinants had ‘desired certificates’ of their examination, as the only evidence many of them had of what they had lost, ‘which we think not fit to deny them’.Footnote 2

Three weeks after that, on or shortly after 4 March, the eight commissioners presented at Dublin Castle a summary narrative analysis of the rebellion, cross-referenced to excerpts from a selection of the depositions sworn before them, and intended for transmission into England as part of what was characterised as a bid to secure charitable relief for the poor plundered ministers of the Church of Ireland and their scattered flocks. The lords justices and seven members of the council expressed their approval on 7 March in a letter of introduction addressed to William Lenthall, the speaker of the English House of Commons.Footnote 3 The commissioners signed off their findings on 8 March, and they were presented to the Commons, at Westminster, by Henry Jones, dean of the diocese of Kilmore, eight days later, on 16 March. The manuscript Jones presented was immediately ordered into print. On 21 March, Jones was granted the copyright and the printed text appears to have been published shortly thereafter.Footnote 4

To some extent, the study of the Remonstrance remains overshadowed by the manuscript collection to which it relates, held, since the first centenary of the revolt's outbreak, at Trinity College, Dublin, bound up in thirty-three volumes and known universally as ‘the 1641 depositions’.Footnote 5 But in recent years, the 1642 text has started to receive the attention it deserves.Footnote 6 Much of the existing scholarship on the Remonstrance pre-dates completion of the monumental project to digitise and transcribe the 1641 depositions, and was prepared without the extraordinary opportunities afforded by online access to the electronic depositions database, hosted by Trinity College Dublin, that has genuinely revolutionised the study of the uprising. This article draws on just some of the riches made freely available by this exemplary piece of scholarship for a digital age.

It presents the results of an investigation into how the Remonstrance was composed and written in Dublin, as well as some of the circumstances surrounding its arrival at Westminster, and its publication in London. The Remonstrance — like Thomas Edwards's monumental, multi-part heresiography, Gangraena — is a text which provides a fascinating window on the process of its own composition.Footnote 7

The influence of the Irish uprising on the outbreak of civil war in England has long been recognised and understood, as has the importance of print media as the means by which that influence operated.Footnote 8 The Remonstrance presents an exceptional opportunity to develop these themes. A quantitative analysis of the commissioners’ labours reveals how the Remonstrance was drafted, and sheds new light on the matter of authorship, providing a basis on which to reassess the aims and objectives of the authors of the Remonstrance and their sponsors in Dublin and Westminster. It may have been a coincidence that the text was presented to the English House of Commons on the very day that the response of the lower House to the king's command expressly forbidding compliance with the militia ordinance balanced the affairs of England ‘on a constitutional knife edge’.Footnote 9 But, as we will see, its arrival there — amidst the controversy over the command of the armed forces which precipitated civil war in England — had been no accident.

The Remonstrance was prepared with more than one purpose.Footnote 10 An older scholarship pointed out the text's focus on the confessional objectives of the rebels, which served as a means of justifying and promoting a crusade in Ireland to counter the threat from international popery.Footnote 11 Aidan Clarke first drew attention to the text's charitable objects, but observed that it was also instrumental to the effort to recruit military assistance in England, and ‘may very well have been intended, as it was certainly used, to promote investment in the reconquest of Ireland’.Footnote 12 Although Joseph Cope has asserted that the text's ‘main aim’ was to prompt the English parliament into accepting its responsibilities towards destitute settlers, its use as a propaganda tool intended to support a ‘colonialist’ case for further extensive confiscation and plantation is undeniable. These were the policy objectives of the faction within the Dublin Castle regime primarily responsible for the Remonstrance. In this article, I will argue that the text should be understood first and foremost as their intervention, made with the intention of promoting their objectives, in the revolutionary struggle over sovereignty then taking place at the heart of the English metropolis.

The article presents fresh evidence that the text's overt charitable objects may have been intended not just to secure humanitarian relief in England on behalf of settlers who had lost everything in Ireland, but primarily to provide plausible cover under which those responsible for the Remonstrance carefully selected then manipulated its source material to deliberate and calculated political effect. It is argued that their aim in so doing was to help isolate and undermine Charles I, weaken his policies of Catholic accommodation, and thus strengthen the position of the English colonialists in Ireland. These objectives had been strongly suspected at the time by some contemporaries. A pamphlet published at Kilkenny in December 1642 alleged that the authors of the Remonstrance had gone out of their way to blame the uprising on the king and queen of England.Footnote 13 In July 1643, the very first of the charges on which James Butler, marquess of Ormond, arrested Sir William Parsons and others involved in sponsoring the Remonstrance, was an allegation that they had ‘taken and published’ evidence of what had happened in Ireland in 1641‒2, ‘endeavouring’, thereby, ‘to asperse’ the king ‘as author of the bloody rebellion in Ireland’.Footnote 14

As we will see, in the absence of an original manuscript of the Remonstrance it remains difficult to make that precise charge stick fast. But there is a strong case, supported by an unexpected abundance of evidence that can be gleaned from forensic analysis of the text itself, and further fortified by a consideration of the surrounding circumstances and the preceding fifteen years of Irish history, for arguing nevertheless that the Remonstrance was a deliberate attempt to strengthen the position of the so-called ‘junto’, the political faction at Westminster led in the House of Commons by the English parliamentarian, John Pym, in its struggle to pry apart Charles I and those ‘evil counsellors’ by whom they insisted he had been bewitched.Footnote 15 And whilst it is questionable whether the impact of the Remonstrance on English politics was exactly as its authors and their sponsors had intended, the damage it wrought can fairly be described as devastating.

I

Historians have often commented on the care with which the Remonstrance went about to lend empirical rigour to the reporting of the Irish rebellion, but have generally been more preoccupied with matters of substance than with the nuts and bolts.Footnote 16 Apart from the Irish council's prefatory letter of introduction, copies of the lords justices’ two commissions dated 23 December 1641 and 18 January 1642, and a summary section at the end, the Remonstrance mainly comprises a compact twelve-page analysis of the origins and course of the uprising in Ireland, heavily footnoted by reference to sixty-two pages of ‘Examinations’.Footnote 17 These were excerpts from seventy-eight statements, a small fraction of the 641 that had already been sworn, mainly by English Protestant settlers who had fled homes in nineteen counties for the safety of Dublin.Footnote 18 Although the gathering of evidence had begun a few days prior, the earliest of the Examinations was dated 3 January 1641 and the latest 4 March 1642, a few days before the text was signed off.

Apart from two excerpts from evidence given before members of the Irish council,Footnote 19 the Examinations had all been collected by the eight commissioners: Randall Adams, minister or parson of Rathconrath, County Westmeath;Footnote 20 William Aldrich, possibly by 1641 the rector of Drumgoon, County Cavan, whence he had fled that autumn;Footnote 21 Henry Brereton, who may have been the minister of Santry in County Dublin of that name;Footnote 22 William Hitchcock, who remains an intractable mystery to me; Henry Jones, dean of Kilmore; Roger Puttock, who described himself as ‘Clark’ of Navan, County Meath, and who is described in other evidence as ‘minister’ there;Footnote 23 John Sterne, vicar of Ballyboy, King's County;Footnote 24 and John Watson, who seems to have been archdeacon of Leighlin.Footnote 25 As we will see, the relative involvement of the commissioners in the gathering of evidence about the outbreak of the 1641 uprising varied a fair bit. However, it is also reasonably clear that all were intimately involved in the work of preparing the data sets from which the Remonstrance was constructed.

One way of getting to grips with the manner in which the Remonstrance was written is to consider first, in outline, the structure of its narrative analysis, before establishing when, how and by whom its underlying source material was gathered, taking as our starting point the Examinations that form the bulk of the text. The commissioners’ twelve-page narrative analysis (that is, ‘the Remonstrance proper’) comprises a short introductory passage of about a page-and-a-half (I will refer to this as ‘Section A’) and is then divided fairly evenly between slightly more than five pages of things that various, mostly nameless insurgents were reported to have said during the course of their revolt (‘Section B’) and slightly less than five pages of things they were reported to have done (‘Section C’).

Section A describes the uprising as the product of a conspiracy of ‘well-nigh the whole Romish sect’, international and domestic.Footnote 26 Section B sets out hearsay evidence for each of the alleged continental, English, Scots and Irish strands of that conspiracy, to which I will refer, respectively, as sub-sections B(i), B(ii), B(iii) — each actually just a paragraph — and B(iv), which is about four pages long.Footnote 27

Section C is also sub-divided, between instances of the insurgents’ blasphemous impiety — actually a kind of hybrid of words and deeds, variously directed at God's servants, worship and churches, as well as ‘our sacred Books of holy Scriptures’ — followed by the familiar litany of indiscriminate physical violence and cruelty inflicted on English Protestant settlers, and ending with an account of the ugly mistreatment of ministers of the gospel in particular, with which the commissioners concluded their text. These I refer to as sub-sections C(i), C(ii) and C(iii) respectively.Footnote 28

Following on from the narrative analysis, the individually numbered Examinations are assembled in a non-chronological sequence, the only order to which is dictated by the structure of the Remonstrance proper. Each substantive point in the commissioners’ analysis is supported by a footnote (denoted by alphabetical sequences of capital letters) and each footnote cites one or more of the numbered Examinations, seventy-three of which then appear, at the back of the text, in the numbered order in which first reference is made to them in the Remonstrance proper. The Examinations numbered 74 to 78 all appear out of sequence in the footnotes and are evidently late additions, being footnoted with an asterisk or ‘x’.Footnote 29

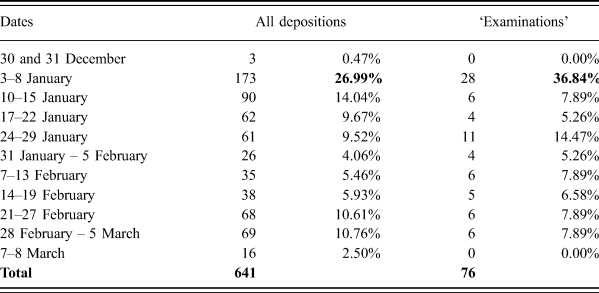

Each of the Examinations is dated, records the names of the commissioners before whom it was sworn and can be traced to its source amongst the 1641 depositions. By reference to the online digital archive, the Examinations can be placed in context, as a sub-set of all depositions sworn in the period. Working with all this data yields some valuable information about the mechanics of drafting. To begin with, I prepared a simple calendar, based on the dates when each of the Examinations was sworn (Table 1), as well as a weekly breakdown of the total number of depositions sworn in the period (Table 2). This exercise revealed some enlightening aspects of the commissioners’ schedule.

Table 1. Examinations calendar

Calendrical distribution of the 76 dated (and numbered) deposition excerpts (two — neither of which were taken by the commissioners — are undated).

Table 2. Weekly totals and percentages of depositions and ‘Examinations’ 30 December 1641–8 March 1642

One immediately obvious feature is the extraordinary industry of the commissioners’ first full week of work, during which they amassed more than a quarter of all the depositions collected down to 8 March, the date on which they signed off their text. Moreover, these included twenty-eight — more than one in three — of all those that turned up in excerpt amongst the Examinations. That means that of all the depositions to which reference is made in the Remonstrance, collected in a period lasting around ten weeks, a disproportionate number were sworn during the very first week. Another noticeable feature of these twenty-eight depositions is that all bar two of them are fairly evenly spread out among those of the Examinations numbered in a range from 9 to 60.Footnote 30 One way of illustrating the special character of these twenty-six depositions is to note that while they were collected in less than a week, between 3 and 8 January (twenty of them on the first three days), they form half of a sub-set of fifty-two depositions (i.e. all those numbered 9 to 60), the other half of which took seven weeks to assemble.

We can build further on these insights by combining our initial structural analysis with a careful review of the commissioners’ evidence-gathering schedule. The Examinations numbered 9, 10 and 11 are the first three references appearing in footnote (H) on page 3 of the Remonstrance (‘footnote 3(H)’). This footnote supports sub-section B(ii), which sets out what the victims of the uprising had been told about alleged English dimensions of the conspiracy which had led to the outbreak of violence in Ireland. Meanwhile, the Examination numbered 60 is the first reference appearing in footnote (N) on page 8, which is the final footnote deployed in support of the claims made for the rebels’ various blasphemies, bringing sub-section C(i) to a close.

There emerges from this exercise in textual archaeology the clear outline of a hypothesis that selection and organisation of depositions began very early, if not immediately; that twenty-six of the depositions selected from those taken between Monday 3 January and Saturday 8 January form the core of what then became an original draft of the Remonstrance; and that the traces of that original draft are discernible from the published text as the sequence of Sub-sections B(ii) to C(i), on to which Section A, and sub-sections B(i), C(ii) and C(iii) were subsequently bolted, fore and aft.Footnote 31 Footnote 3(H), and particularly Examinations 9, 10 and 11, will be considered further later. But in the meantime, it can plausibly be proposed that it had been intended, from very early on, possibly even before the commissioners started work, to produce a report in the nature of the Remonstrance.

This is the tacit assumption of every previous account of the text as a piece of New English propaganda. Providing some analytical support for this hitherto unspoken understanding affords a new vantage point from which to assess the aims and objectives of all involved. For now, however, we can postulate, based on the foregoing, that the two sections of the text most obviously designed to elicit charitable relief — subsections C(ii) and C(iii), describing the sufferings of the English settlers and their ministers — may well have been added later to an initial working draft. Those subsections may not have been afterthoughts as such. But it is at least arguable that they were additions to an original plan to which they had been secondary in priority.

Meanwhile, this structural and mechanical analysis of the Remonstrance also sheds some useful new light on the issue of authorship, if again with some fairly unsurprising results. The Remonstrance is known by a settled convention as the work of Henry Jones, son of Lewis Jones, bishop of Killaloe, and nephew of James Ussher, archbishop of Armagh.Footnote 32 Joseph Cope has called the Remonstrance ‘Jones's version of events’, but has also referred to Jones — more guardedly than most — as the ‘principal author’ of the text, impliedly conceding the ‘influence’ of the other seven commissioners on ‘the final form of the Remonstrance’, but remarking that the extent and nature of that influence ‘is difficult to gauge’.Footnote 33 Quantitative analysis of the text offers a number of ways in which that difficulty can be overcome and provides an instructive counterpoint to the convention.

A review of the depositions collected in the first two months or so, reveals that the vast majority — just over 94 per cent — were witnessed by two of the commissioners each.Footnote 34 It also demonstrates that none of the commissioners witnessed more than around two-fifths, and some (including Jones) only a quarter, one-fifth or even fewer (Table 3). As a result, none of the commissioners, working on their own, would have been in as good a position to form a full picture of the data from which the Remonstrance proper would be derived as they would have been working together. Meanwhile, all eight commissioners signed the finished text not once but twice, the lords justices and members of council wrote to Speaker Lenthall on behalf of them all, and Jones is described as their ‘Agent’, both by the commissioners, and by Jones himself.Footnote 35

Table 3. Number and proportion of depositions and Examinations witnessed by each commissioner

All this tends to suggest that the Remonstrance was in fact the collaborative effort that it was certainly presented as being at the time. Given the sheer volume of evidence, and the pace at which it was assembled, it is most unlikely that one of the commissioners could have written the text on his own, except in the capacity of either a scribe or secretary (a possibility which may explain the very small number of depositions personally witnessed by Randall Adams). It may be more accurate to describe Jones as the leader of the team that researched, co-wrote and edited the Remonstrance, rather than as the text's ‘author’.

It is noticeable, for example, that Jones witnessed 35 per cent of the twenty-six depositions at the core of our notional working draft, but fewer than 20 per cent of all 641 depositions sworn in the period, indicating a level of initial involvement that subsequently reduced significantly, perhaps as his focus shifted from establishing the strategic direction at the outset, to overseeing its delivery. It may also be significant that although, overall, Jones had witnessed fewer than one in five of the depositions sworn between 30 December 1641 and 8 March 1642, that sub-set was disproportionately represented amongst the Examinations, Jones having witnessed one in four out of the seventy-six depositions around which the Remonstrance came to be written. On that basis, then, Cope's ‘principal author’ seems perfectly apt. But perhaps the nail is hit most squarely on the head by Toby Barnard's description of Jones as the commission's ‘key worker’, capturing some of the political element to his appointment.Footnote 36 Jones was the first-named commissioner, the most senior in rank, and much the better connected of the eight.

Constraints of space do not permit a fuller treatment of the results emerging from a quantitative analysis of the Remonstrance. But one singular feature that emerges from a reconstruction of the commissioners’ schedule is the swearing of just one of the deponents on a Sunday. Thomas Crant of the county town of Cavan swore his testimony on Sunday 13 February 1642.Footnote 37 Crant's is not just the only one of seventy-six Examinations sworn on a Sunday: it was the only deposition sworn on a Sunday out of all 641 sworn down to 8 March. On closer inspection this turns out to be of considerable potential significance. As Eamon Darcy has recently noted, an English parliamentary declaration dated 7 March 1642, and published days before Henry Jones arrived at Westminster with the Remonstrance, expressly cited Thomas Crant's deposition in support of its claims about a purported intention the previous autumn to coordinate Catholic insurgency in both Ireland and England.Footnote 38 Second, we can reasonably infer that the only reason this 7 March declaration referred to Crant's deposition was because he had taken it in person to Westminster, and that the doors to some fairly exalted company were immediately opened to him when he arrived. As well as making contact with those who wrote the 7 March declaration, who included none other than John Pym himself, on 8 March Crant was even presented at the bar of the lower House by Oliver Cromwell, the rising star of the puritan populists.Footnote 39

Crant's sudden, high-profile appearance, in the cockpit of English politics, amidst the gathering constitutional storm, established a vital connection between the authors of the 7 March declaration, and the work that was by then rapidly nearing completion back in Dublin. Coincidentally, on the same day that Crant's deposition was cited at Westminster the eight commissioners were at Dublin Castle presenting the final draft of their Remonstrance to the lords justices and members of the Irish council for their approval. What their text said would appear amply to substantiate some of the claims made at Westminster on 7 March — not just about efforts to coordinate Catholic insurgency on either side of the Irish Sea, but also about an Irish uprising alleged to have been ‘framed and contrived in England’.Footnote 40 It is these particular features of the Remonstrance which I believe reveal the true significance of the arrival of, firstly, Thomas Crant and, then, Henry Jones at Westminster in March 1642.

II

As already mentioned, the Remonstrance sought to explain the uprising of 1641 as an international conspiracy of ‘the whole Romish sect’, seated in Ireland but orchestrated with, and supported by, the chancelleries of Catholic Europe. The uprising's alleged English dimensions, however, are afforded particular significance. The text begins, for example, by alleging the ‘instigation’ of the uprising by a combination of ‘Popish Priests, Friers and Jesuites, with other fire-brands and Incendiaries of the State’ already resident in Ireland, as well as those ‘flocking in from Forraign parts, of late in multitudes more then ordinary’ and ‘chiefly by such of them as resorted hither out of the Kingdom of England’.Footnote 41 Moreover, based on the analysis set out above, there is a good case for saying that the textual remnant of the initial working draft of the Remonstrance actually starts with the allegation — set out at sub-section B(ii) of the published text — that the insurgents in Ireland ‘had their correspondents in England, for raising the like Rebellion there’. In other words, this was a claim which the commissioners had originally intended to foreground, only later moving it down the running order.

A crude measure of the significance attached by the commissioners to this ‘correspondents’ claim is the fact that it is supported by the lengthiest of all their ninety-one footnotes. Footnote 3(H) cited no fewer than nine Examinations — more than one in nine of the commissioners’ total selection, and more than the eight, spread over four footnotes, cited immediately beforehand in illustration of the insurgents’ claims (with which the commissioners’ published text ended up leading) that they were receiving support from ‘beyond the Seas’, and specifically from Rome, Madrid and Paris.

Notably, also (and as touched on earlier), the first three sources in the ‘correspondents’ footnote were dated 4 and 5 January 1642, having been picked out from amongst the first 100 or so depositions the commissioners had sworn on the first three days of their first full week of business, and chosen (on my argument) as the point of departure for the entire enterprise. This hypothesis, if correct, would have some fairly startling implications.

The three Examinations in question were excerpts from the depositions of John Brooks of County Cavan and two women from County Fermanagh, Elizabeth Coats and Grace Lovett.Footnote 42 All three testified to encounters with rebels who had warned them, at the point of, or during, their flight from their respective homes, that there was no point seeking refuge across the Irish Sea, for England was ‘in the same case’ as Ireland, according to those with whom Brooks spoke, Coats saying she had been told things were ‘as bad’ there, Lovett that they were ‘worse’. Here was ample evidence — in accord with Thomas Crant's — supporting the allegation made at Westminster on 7 March that it had been intended ‘that the English Papists should have risen about the same Time’ as their co-religionists in Ireland.

This in itself was not a particularly remarkable claim to advance by the spring of 1642, given how terrified so many people in England had been in November and December 1641 of an imminent Catholic uprising. But what Brooks, Coats and Lovett had told the commissioners went significantly beyond the frightening things various insurgents had told them about conditions in England. John Brooks had told the commissioners he had heard the claim made, amongst the insurgents, ‘That what they did, they had authority for the same from the King, or words to that effect’. Elizabeth Coats gave evidence that some of the rebels had said to her ‘that what they did, they had the Kings Commission for it’. Margaret Lovett testified that an unidentified ‘Friar’ had claimed that ‘We have the King's broad Seal for what we do’.

The commissioners introduced the depositions of Brooks, Coats and Lovett as evidence that the Irish insurgents had claimed they had ‘correspondents’ with plans to shed Protestant blood in England, only to reveal an allegation that the insurgents’ chief co-conspirator there was Charles I himself. But significant though it is that the commissioners’ putative working draft may have begun with such an earth-shattering allegation, this was very far from all. Brooks, Coats and Lovett were just the tip of the very large iceberg that the commissioners would now bring to the attention of their aghast English readership. No fewer than twenty of the Examinations — just over one in four — referred expressly to claims made to regal authority and even direction (including, just three times, the queen's).Footnote 43 Three quarters of the references involved insurgents’ claims as to the existence of some physical instrument or other, whether a commission or a warrant or similar. Reference was made six times to the king's broad seal.

Although this feature of the text has hardly gone unremarked in the past, historians have overlooked its significance in implicating the Remonstrance amongst the short-term reasons for the outbreak of civil war in England. The allegation that Charles I had issued a commission, authenticated by his great seal, authorising the Irish uprising, is so notorious, so notoriously false and its disastrous impact on English political culture so well-attested, that nobody has ever observed the remarkable fact that in all likelihood that allegation was never actually made, publicly, or with any kind of authority, before the Remonstrance appeared on booksellers’ stalls in London, by order of the English House of Commons, five months after the Irish uprising started.Footnote 44

Multiple sources had reported early on that the Irish insurgents had claimed to be acting in defence of the king and the royal prerogative, against the trespasses of his ‘puritant’ enemies — claims those same insurgents had published several times themselves.Footnote 45 Claims had been made too that some of the insurgents were describing themselves as the queen's own army.Footnote 46 But a review of the parliamentary journals, state papers, correspondence to and from Dublin Castle and the deluge of texts which flooded English markets for print media in the autumn and winter of 1641–2 has yet to reveal a single secure ‘public’ reference to claims made by the insurgents that they had the authority of King Charles himself for what they did, much less a commission authenticated by ‘the King's broad Seal’.Footnote 47

Given how widespread were the reports that the insurgents had asserted regal authority, their claims seem to have registered in the public record in only the most suspiciously opaque way. On 30 October 1641 the lords justices issued a proclamation in which they referred enigmatically to attempts by the insurgents ‘to gain the more Numbers and Reputation to themselves and their Proceedings in the Opinion of the ignorant common People’ by means of certain unspecified ‘false Seditious and scandalous Reports, and Rumours’. Parsons and Borlace self-consciously asserted ‘that We have full Power and Authority from his Majesty to Prosecute and Subdue those Rebels and Traytors’, from which it could perhaps be surmised that whatever it was the insurgents had said might have called in question such ‘Power and Authority’. But there was no proper basis here from which to infer the rebels’ claims that they themselves were acting by royal authority.Footnote 48 Strikingly, even when writing to the Lord Lieutenant himself, on 14 December, the Irish council avoided informing him that the insurgents had claimed to be so acting, saying only that in order to ‘cover their treachery’, they ‘pretend audaciously that what they do is for his service’, claiming that ‘many thousands … are under countenance of His Majesty's name seduced to their party’. By contrast, on 12 December 1641, New English councillor Sir John Temple had written to the king himself, to tell him expressly that there were insurgents who claimed to have his royal commission for what they were doing.Footnote 49

In England, a letter from a member of the judiciary in Ireland, ‘Mr. Justice Mayern’ (presumably Sir Samuel Mayart),Footnote 50 was read in the House of Commons on 30 November 1641, apparently stating that in County Wicklow ‘they reporte that they have done nothing but by Warrant or directions from the Kinge’.Footnote 51 In reaction, the Commons ordered its Committee for Irish Affairs to ‘prepare Heads for a Conference with the Lords, concerning a Declaration to be made, for the Clearing of his Majesty's Honour from false Reports cast upon him, by the Rebels in Ireland’.Footnote 52 But again, there was no real clue given as to what those ‘Reports’ might have been and in the end no such declaration appears to have been issued anyway. The Commons did not even record the existence of Mayart's letter in their own journal. Neither does there seem to have been any public notice given when, on 3 December 1641, the Commons read a letter sent from Lancashire to Alexander Rigby, member for the town of Wigan. Rigby's correspondent, one Hopton, relayed information told to him by a refugee from Ulster, Edward Briers, that the rebel commander Sir Phelim O'Neill had ‘shewed his souldiers a Commission under the broad seale of England, by which he saied that he was authorized by the King to restore the Roman religion in Ireland’.Footnote 53 Hopton's letter does not appear in the Commons’ Journal either.

So many Protestant settlers had fled back to England in the winter of 1641‒2 that it is inconceivable that stories such as these had not circulated widely there, from very early on. And in an age when practically any rumour could be touted as fact on the floor of the English House of Commons, then reported far and wide, the seemingly total public silence on this score until March 1642 might suggest that some last vestige of a discreet circumspection had survived the storms of popularity that had wracked English politics for eighteen months. If so, then it was in fact the 7 March declaration which referred to the sworn testimony of Thomas Crant that seems to have changed everything.

Conrad Russell has pointed out that the militia ordinance had passed both Houses two days earlier and that the Commons drew up their latest declaration ‘believing the gloves were off’, preparing a draft ‘which [parliamentary diarist, Sir Simonds] D'Ewes thought “too fierce and sharp”’.Footnote 54 Far more startling than its claim that the Irish uprising had been ‘framed and contrived’ in England was its reference to ‘the boldnes of the Rebels in affirming They do nothing but by Authority from the King’.Footnote 55 So far as I can tell, this was the very first time that anybody in England had dared say publicly, and in print, something of which no doubt many would have been well aware privately already, and which at least some in the Commons had certainly known about, but had been sitting on for over three months.

It is true that on 7 March the Commons had received, and referred to the Lords, a letter from the mayor of Plymouth, Thomas Ceely, reporting that one Mark Pagett, dean of Ross, had alleged that (amongst other things) ‘the Irish Rebels doe report that they have the Kings Warrant and Great Seale for what they doe’.Footnote 56 But the 7 March declaration does not mention Ceely's letter and none of the material offered in the declaration actually evidenced the ‘boldnes of the Rebels’ to which it referred. Meanwhile, its authors did not even cite Judge Mayart's letter that appears to have supported the claim almost word for word. It is in my view highly likely, therefore, that this allegation, about the rebels ‘affirming They do nothing but by Authority from the King’ was made by men emboldened substantially by the news, brought to Westminster by Thomas Crant, that evidence was being gathered in Dublin, by the armful, from witnesses who had sworn on the bible that they themselves had personally heard insurgents make such claims.Footnote 57

Moreover, it is reasonable to suggest that Thomas Crant had been sent to herald the impending despatch of all that evidence from Dublin. His arrival at the pinnacle of English politics would appear too precipitate to be explained any other way. Given Crant's stratospheric ascent from total obscurity to star witness inside three weeks, there is more than a suggestion that his unique achievement in swearing his evidence on a Sunday had indicated the urgency of the affairs of a man on a mission, quite possibly with a boat to catch.

III

Understanding the significance of Crant's mission requires some careful attention to the text that turned up in the House of Commons about a week after him. This exercise is complicated in the absence of the manuscript with which Henry Jones arrived on 16 March. Structurally the Remonstrance probably did not change between its despatch from Dublin on 8 or 9 March and its publication two or three weeks later. But its content would most likely have evolved significantly from the form it had probably attained by the time Crant had left Dublin, about a month earlier. It was no doubt quite a bit longer by then. More substantively, the English dimensions of the uprising may have ceased featuring quite as prominently.

As already noted, the published text begins by describing an international conspiracy, involving a host of outside agents, ‘chiefly’ from England. But the burden of the opening passages — Section A and sub-section B(i) — was an allegation that the insurgents ‘hath been confederate with forraign States’, and had acted with support and assistance from Spain, France and Rome, such that ‘[i]t doth’ only ‘secondly appear,’ said the commissioners, ‘that they had their correspondents in England’.

We might legitimately wonder whether the commissioners had ‘buried the lede’, partially concealing or obscuring the feature of their story reasonably regarded as its most newsworthy. A lede can be buried unintentionally, through failure to recognise the importance of some aspect of a story.Footnote 58 In this case, the strong suspicion must be that the commissioners had been in no doubt at all as to the aspect that they themselves regarded as the most important, but had considered it appropriate to reduce its prominence. Close reading of the Remonstrance reveals that this is a technique characteristic of the text as a whole.

Suspicion that the commissioners had sought to reduce the emphasis on the English dimensions of the insurgent conspiracy is strengthened by the manner in which the evidence for rebel claims to the king's authority was actually deployed. Paradoxical as it may seem, given its sheer volume, the word with which it can perhaps best be summed up is: covertly. From the start, readers of the Remonstrance were directed to the evidential support for the text's numerous footnoted claims, all set out in the numbered, cross-referenced Examinations. Readers who followed the commissioners’ cues stumbled upon reference after reference to the king's appointment, authority, broad seal, commission, consent, direction, ‘license’ or warrant. The effect is to convert the sixty-two pages of Examinations into a kind of evidential minefield, strewn throughout with explosive claims, into which readers were ushered with hardly a word of warning or guidance.

Having allowed their readers to alight upon several such references, left for them to find in half a dozen different footnotes,Footnote 59 the commissioners did eventually get around to expressly addressing the insurgents’ claims to have the king's authority, saying that ‘for making the more plausible introduction into their wicked Rebellion, the Conspirators aforesaid, have traiterously, and impudently averred and proclaimed, that their authoritie therein is derived by Commission from his Highnesse’.Footnote 60 But in substantiation of their tardy observation the commissioners cited just two references. In other words, fully 90 per cent of all the evidence that such claims had been made was advanced in substantiation of something else entirely.

We have already seen how this operated in the case of Brooks, Coats and Lovett. Introduced by the commissioners to tell of rumoured ‘correspondents in England’ plotting the same slaughter and mayhem there as they had witnessed in Ireland, the excerpts from their evidence showed not only that they had been told, by insurgents, that things were as bad or worse across the Irish Sea but that they had also been told that the king had authorised what they were doing. At least in the case of these three, this additional information made a kind of inferential sense: of course things were as bad or worse in England, if it was the king of England himself who had made things as bad as they were in Ireland. But in many other instances, the evidence of claims for the king's authority was advanced, as it were, à propos of nothing.

To take perhaps the most notable example, the testimony of Jathniell Mawe, a gentleman from County Fermanagh, was cited by the commissioners in support of probably the most notorious allegation of the entire text (one that helped shape debate on the uprising for the next 250 years or so): the allegation that the rebels had intended nothing less than ‘a generall extirpation, even to the last and least drop of English blood’.Footnote 61 In making out that central claim, advanced on page 7 of the Remonstrance, the commissioners had really not needed to include, on page 57, Mawe's testimony that ‘he heard some of the Rebellious Irish company say … that they had the Kings Broad-Seal for what they did’. But plainly the temptation was too great, for there it is anyway.

At least Mawe's published testimony is in the exact form of his original deposition, sworn on 3 January 1642.Footnote 62 In a more egregious instance, Nathaniel Higginson's evidence was cited in support of claims that certain rebels said that, having overrun Ireland, they would join with Spain and France to overrun England, and that the rebels had been told by their priests not to finish off grievously wounded victims, but to leave them lying ‘that these wretches might languish in their miserie’. When setting out their excerpt from Higginson's deposition, the commissioners included his testimony supporting the first claim, about the rebels’ bold ambitions. But they actually omitted altogether the passage describing the alleged cruelty of the priests — and yet they included Higginson's report that the rebels had made reference to ‘a Commission, or Broad-Seal from the King’.Footnote 63

Of course, other factors are potentially at play here, having to do with the kinds of publishing, copy-editing and even type-setting decisions involved in calculating the most efficient use of the eleven sheets of paper used in the printing of each copy of an 88-page quarto volume. But the sheer quantity of the references to the claims made about the king's authority makes the pattern of authorial intent too obvious to ignore, and there is no reasonable basis on which to postulate that these kinds of editorial decision might have been made anywhere other than Dublin.

Moreover, it is interesting to note that, laid end-to-end, all these very largely incidental references to the king's authority, broad seal, commission and so on, probably occupied maybe half a page or so. The inclusion of all that material presumably helps in part to explain why the accounts of two deponents named by the commissioners in their footnotes did not ultimately appear amongst the Examinations. As a result, and although the commissioners had plainly intended including it at one point, the Remonstrance omits the evidence of the only eyewitness who personally survived the notorious mass murder at the bridge over the River Bann near Portadown. But it is noteworthy nonetheless that the evidence of William Clarke ended up being spiked, at least partly, in order to make room for perhaps four or five times as many references to allegations of royal authority as might have been strictly necessary in order to get that particular point across.Footnote 64

IV

It is in seeking to explain decisions regarding the selection and presentation of the sub-set of the evidence deployed in the Remonstrance having to do with alleged royal authority for the uprising that we alight on some new ways of thinking about the text's aims and objectives. It is extremely difficult to describe something to which reference is made twenty times in the space of sixty-two pages as having been ‘hidden’ by the commissioners. Rather, their treatment of the evidence regarding the insurgents’ claims to have royal authority seems to have been an act of ‘serial covert disclosure’: the least demonstrative way of drawing as much attention as possible to evidence that such claims had been made, without appearing too obviously to have intended drawing so much attention to it.

This, like the text's ‘buried lede’, is a paradoxically revealing act of (partial) concealment, tending to suggest that all those involved in the preparation of the Remonstrance had been alive to the potential consequences of bandying such toxic material. We might legitimately begin to wonder whether the men who composed the Remonstrance, whatever they might say in purported refutation of the things the rebels had ‘traiterously, and impudently averred and proclaimed’, were actually trying to increase the likelihood that their readers would entertain the possibility that Charles I might have been responsible for the suffering of his New English subjects in Ireland.

There is at the very least a strong suspicion that all involved had known exactly what they were doing, and that what they were doing was not going to reflect well on the king. Much if not all of the evidence examined so far demonstrates a fairly transparent attempt to establish the putative existence of a trail of blood leading from Ireland all the way to the gates of the royal household and even to the doors of the king's own privy chamber. More remarkably still, after the commissioners had gone out of their way to summon up that particular mental image, somebody seems then to have worked very deliberately to scrub from the record almost all trace of the king's own fingerprints.

The depositions of six of the fifteen witnesses cited in the Remonstrance who had referred to a physical instrument recorded that the insurgents claimed it had been signed by the king, or the queen, or both. And yet the excerpts in the Remonstrance of the evidence given by five of these six — John Biggar, John Mountgomery, John Shorter, Henry Palmer and Edward Slack — all omit to mention this arresting detail.Footnote 65 The exception that proves the rule, the published evidence of Henry Raynolds, was ambiguous, being capable of bearing the construction that what the king had signed was English legislation for the extirpation of Irish popery.Footnote 66

Historians are well aware that the commissioners deliberately crafted the raw evidence they had gathered into forms that might better suit their purposes, whether to depict ‘the Irish’ as uniformly savage or their victims as universally pitiable. More forensically, David Greder has identified omission from the published text of stories the commissioners had been told by Biggar and Mountgomery, about the claims some insurgents made that they were acting in defence of the king's prerogative rights.Footnote 67 Omissions such as those make sense: the commissioners had obviously not wanted to lend credence to the fact that many of those whom they were keen to depict as ‘rebels’ considered themselves to be the king's loyal subjects. It is more likely than not that decisions on this score were likewise made in Dublin, and that Jones arrived at Westminster with a text which sought to show that the uprising was an attempt by the perfidious Irish papists to subject Ireland to foreign Catholic powers and the jurisdiction of the Church of Rome.Footnote 68

Assuming that the references to the king's hand were also deliberately omitted, it can really only be explained as an attempt to suppress any suggestion of a direct physical connection between the person of the king and the alleged administrative act of authorising the anti-English pogrom. It would be possible to interpret this as evidence of a desire to shield the king from accusations of command guilt for attempted genocide were it not for the quite extraordinary degree to which the authors of the Remonstrance had gone out of their way to drag him into the whole sorry business in the first place, not just in passing, but serially, and insistently, even relentlessly.

This erasure of the king's hand seems to serve quite a different purpose. It is what brought the trail of blood leading from Ireland to an abrupt, figurative halt, not at the king's own bureau but right outside the royal suite. It threw a pall of suspicion more widely, over those closest to Charles I, those who might have obtained illicit access to the instruments of regal authority, in order to wield them to their own despicable ends.Footnote 69 In all likelihood, there was one person upon whom the Remonstrance was intended to cast such suspicion. The text begins, as we have seen, with the claim that the 1641 uprising was the product of an international conspiracy. The very first footnoted claim was that it had been ‘confessed’ by the rebels ‘that they had their Commission for what they did from beyond the Seas’. To back up that claim, the commissioners cross-referred to Examination 1, an excerpt from the evidence of John Day, a weaver from Drumleiff in County Cavan. Curious readers, flicking forward to page 17, found there rather more than they might perhaps have expected. For what John Day had told the commissioners was that ‘the Rebells … said [to him] that they had a Commission from the Queene’.

V

We do not know, and probably never will, who was responsible for suppressing claims that the king personally authorised the uprising, and we know just enough about surrounding circumstances for that doubt to make a difference. We know for example that the deposition of Henry Jones himself was sworn on 4 March 1642, just days before he left Dublin, but that an addition was made to it before it was published. Given that the new material was plainly intended to deflect from the leaders of the English House of Commons the blame, indisputably at least partly theirs, for the presence in Ireland in October 1641 of the Catholic soldiers, raised by the late Earl of Strafford, who would find themselves in the van of an armed uprising (despite their recruitment that summer to the service of armies abroad), it was almost certainly added at Westminster.Footnote 70 So it is within the realm of conjecture that any deliberate erasure of the king's hand constituted finishing touches to the Remonstrance, applied after the manuscript arrived in England. That said, there are a number of reasons why the finger of suspicion points more firmly in the direction of Dublin. In short, it did not require the machiavels at Westminster to see the potential advantages of ensuring that the evidence remained amenable to multiple constructions.

For example, we have noted that evidence of the rebels’ claims that they were defending the king's prerogative was omitted from the excerpts, published in the Remonstrance, of the evidence given by John Biggar and John Mountgomery. Alterations of that nature were much more likely to have been made in Dublin than at Westminster, by the appointees of a colonial government that had already done what it could to obscure such things. It is a reasonable assumption that Biggar and Mountgomery's references to the king's hand were erased at the same time.

The circumstantial evidence against the Dublin regime and its commissioners is suggestive. Amendments of this nature would be consistent with the editorial decision, postulated above, to reduce the prominence of the rebellion's English dimensions and to heighten the emphasis placed instead on the role of Catholic powers — and with the partial concealment of the rebels’ claims to be acting by the king's authority. Those amendments are consistent too with the fact, that only became apparent upon publication of the text, that nobody in Dublin Castle had told the king what they and their commissioners were doing and had (more than likely) sent Thomas Crant to Westminster to tell John Pym and his crew about it instead.Footnote 71 The commissioners’ hasty attempt to ‘make amends’ — no doubt under pressure from the king — by publishing a further, much shorter selection from the depositions, more clearly demonstrating that the rebels had risen up against Stuart authority in Ireland, rather than as some purported expression of it, appears to have persuaded nobody, at the time, that all the damning innuendo about an alleged royal authority for the rebellion had somehow found its way innocently and unwittingly into print.Footnote 72

Another argument fixing responsibility for the manipulations of the text with the commissioners, and ultimately their Dublin Castle sponsors, is motive. Almost all of the signatories of the text's letter of introduction were members of what Robert Armstrong has termed ‘an inner group within the council’, who had been working for months to thwart political solutions to the uprising, and to promote its violent suppression instead, thereby enabling wide-scale confiscation of insurgents’ property.Footnote 73 This faction was led by Sir William Parsons, and its members had long been engaged in a struggle, stretching back some fifteen years, to promote an ‘anti-Catholic, plantation agenda’, and to impede implementation in Ireland of the Graces, a tool of Caroline Irish and foreign policy that had offered legal protections for Catholics under the umbrella of Stuart personal rule.Footnote 74

War with the Scots covenanters in 1639‒40, and the ensuing struggle at Westminster in 1641‒2 to contain the prerogative powers of Charles I, had prompted the king to revive the Graces, as a means to obtain and exploit fiscal and military resources in Ireland. But at the same time these crises of Stuart monarchy had presented others with an opportunity to bury forever threats such as these to the entrenchment of colonialist supremacy in Ireland, and to cut off at source the succour they would have afforded to the kingdom's Catholics.Footnote 75

By the summer of 1641, Catholic commissioners sent from Dublin had all but agreed terms with the king. In August, the Irish council sponsored an adjournment of the Irish parliament, with a view to blocking legislation implementing many of the Graces, lending considerable motive force to the conspiracy that broke out into rebellion two months later. The councillors had acted, they said, in order ‘to accommodate our apprehensions in his Majesty's behalf’ — effectively telling the king how his personal prerogative should be wielded in his own interests.Footnote 76 It was in much the same spirit that the inner group would conspire with the junto at Westminster in December 1641 to stymie the efforts of Lord Dillon to broker a deal between the king and the lords of the Pale that might have ended the uprising.Footnote 77

The intertwining of confessional and constitutional struggle in Ireland, and attempts to recruit at Whitehall and at Westminster some assistance in that struggle, provided the context in which Armstrong's ‘inner group’ commissioned and sponsored the Remonstrance. The text opens with the complaint that the rebellion had broken out largely ‘by reason of the surfet of that freedome and indulgence, which through Gods forbearance for our tryall, they of the Popish faction have hitherto enjoyed in this Kingdom’.Footnote 78 This was as good as to blame the rebellion on the policy of dangling ‘matters of grace and bounty’ before the eyes of the Catholics, as a means to win their loyalty.

The commissioners also sought to ensure that readers knew and understood where the real root of the problem lay. We have seen how they hauled the queen into the spotlight, even before there had been any mention of the king, as a hook-line for the text's conspiratorial content. They also retailed another explicit allegation that it was the queen who had sent the rebels’ commission, as well as several rebel claims to the effect that they had risen up to avenge the encroachments of the English ‘puritants’ on the queen's religious liberty, and in particular the (fantastical) murder before her very eyes of her own confessor.Footnote 79 Finally, on the reasonable assumption that by the end of 1641 the strategy of hounding ‘evil counsel’ out of the Stuart realms was the common cause of the ‘inner group’ at Dublin and the junto at Westminster, suspicion plausibly falls most heavily on those first on the scene, who not only had a motive for the manipulation of the deposition evidence but also the opportunity.

There were grave dangers in retailing uncorroborated hearsay about the kind of treasonable claims the Irish insurgents were reportedly making and it was the lords justices who provided the mechanism whereby the seditious slander that the king had authorised the uprising (for that is how it would have been treated by any English sessions judge)Footnote 80 had been converted into evidence taken under oath and sworn on the bible. The first commission issued to Jones and his team placed the recording of ‘traiterous or disloyall words [and] speeches’ in priority to any accompanying ‘violence or lewd actions’, while it is perfectly clear that those behind their appointment, and the drafting of their terms of reference, had known exactly what the commissioners were going to be told in this regard. Given that it was not until nearly a month later that the commissioners were instructed to record those murders and other deaths occasioned by the uprising, for which the depositions are most notorious today, it is possible that rendering the insurgents’ claims to royal authority politically safe to handle, under cover of the certification of their victims’ sufferings and losses, had been the unspoken object of the entire project.Footnote 81

VI

In conclusion, there is a decent case for saying that A remonstrance of divers remarkeable passages was a deliberate, underhand and — in certain, critical respects — fundamentally deceitful intervention in the revolutionary confrontation unfolding in England. It was a text devised in Dublin as part of an effort to make common cause with those at Westminster best placed to eliminate the influence of Catholics and the ‘popishly-affected’ at the court of Charles I, the ‘evil counsel’ who, from a colonialist perspective, posed the greatest risk to the re-establishment, deeper entrenchment and longer-term security of planter hegemony in Ireland. Seen in this light, the Remonstrance provides a convenient reminder that the covenanter regime in Edinburgh was not the only power-affinity based outside England having a profound interest in the state of politics and the outcome of revolutionary struggle at Westminster. The Remonstrance helps confirm the existence of those Anglo-Irish dimensions tentatively deduced by Jason Peacey from his model of ‘a British public’ as a ‘constituency’ whose agitation, by a variety of incendiary texts, served to support those seeking a transformation of the constitutional and ecclesiastical arrangements within and amongst the Stuart realms in the early 1640s.Footnote 82 The contribution of the Remonstrance to that process would prove to be at least as powerful as any of the others.

Looking back, Edward Hyde judged that the insurgents’ claim to be acting with royal approval ‘made more impression upon the minds of sober and moderate men … than could be then imagined or can yet be believed’.Footnote 83 Richard Baxter held that of all the matters which ‘hastened the War’ in England ‘there was nothing that with the People wrought so much, as the Irish Massacree and Rebellion’, and that the insurgents’ claim to have a commission from the king served ‘to increase the Flame … which though the soberer part could not believe, yet the credulous timerous vulgar were many of them ready to believe it’.Footnote 84 It is unclear whether Baxter would have included Nehemiah Wallington amongst such people. But in the London woodturner's world, a direct connection could later be drawn between the king's alleged commission of the slaughter in Ireland and the shedding of his own blood in 1649.Footnote 85

The Remonstrance's authorised revelations enabled such connections to be made, and it appears thereby to have caused severe damage to the prospects of Charles I and his opponents in England achieving a tenable political compromise. It was evidently in reaction to reading the Remonstrance that the king resolved at the start of April 1642 — five months after the uprising began — to go in person to Ireland. He opened his 8 April declaration on the matter by saying that not only was he ‘grieved at the very Soul for the Calamities of His good Subjects of Ireland’, but also

most tenderly sensible of the false and scandalous Reports dispersed amongst the People concerning the Rebellion there, which not only wounds His Majesty in Honour, but likewise greatly retards the reducing of that unhappy Kingdom, and multiplies the Distractions at Home, by weakening the mutual Confidence betwixt Him and His People.

To rectify these situations, the king declared he would take to Ireland a brigade comprising 2,000 foot and 200 horse, which he intended to arm — as he expressly informed the two Houses — from his armoury and magazine at Hull.Footnote 86 With that decision, and the ensuing competition for physical possession of the town, any lingering hopes for the peaceful resolution of political conflict in England were dealt a blow from which they would never recover.

Forty years ago, Aidan Clarke remarked that from a Dublin perspective ‘it was unprofitable’, in 1642, ‘to appear to take sides in English disputes’.Footnote 87 In a similar vein, Robert Armstrong has argued that in 1642 ‘Protestant Ireland, for the most part, remained resolute in standing aside from the quarrels in England’ and that ‘the council in Dublin’ was ‘reluctant to declare … an allegiance’ to either side.Footnote 88 As true as that may have been, it now seems reasonably clear that some of those involved were engaged in a charade. It has been argued here that the Remonstrance was an attempt to take sides without obviously appearing to do so. Having omitted to tell him first, the king's governors of his kingdom of Ireland, and a faction within his royal council, all acting in the king's name and by the authority of ‘his Sacred Majesty’, as the text's authors reflexively called him, had effectively commissioned the small mound of evidence that would create a firm, fixed and ultimately fateful association between Charles I, his closest advisers and the bloodshed and mayhem of the Irish uprising. They then placed it all in the hands of John Pym.

That they knew what they were doing seems to me beyond reasonable doubt. Whether they went about doing it in a way best calculated to achieve their ends is another matter. Clarke also once explained the alignment of Irish and Old English interests in 1641‒2 by reference to a shared dread that curtailment of the king's ‘royal grace’ in Ireland, as a ‘bulwark’ against rampant English puritan populism, would spell ‘disaster’ for Catholic Ireland.Footnote 89 This article has argued that A remonstrance of divers remarkeable passages was commissioned, drafted and promoted in an attempt to instigate exactly that disaster. Its principal effect, however, was to help precipitate the civil war conditions in England that would prolong and exacerbate the disaster that had befallen Protestant Ireland in the autumn of 1641.Footnote 90